Abstract

This study offers the first detailed examination of the materiality of World War One hardtack biscuits – a dense biscuit made from flour, water and salt, which was a key component of ration packs for both Australian and British soldiers. It is specifically concerned with the types of repurposing – or acts of semiotic remediation – that take place, their broader sociocultural functions and the semiotic resources drawn upon to make meaning. Using a combination of multimodal analysis and archival research, it identifies five key acts of semiotic remediation by soldiers – declarations of ownership, letters, diary entries, photo frames and objets d’arts – which showcase hardtacks as unique, unmediated resources for understanding WW1 experiences. It also notes the frequent use of humour as a coping mechanism, as well as the important memorialisation function of hardtacks, acquiring symbolic values disproportionate to their everyday value for bereaved families. Hardtacks, thus, stand as a testimony to the resourcefulness of humans in trying circumstances, holding a wealth of knowledge on the aestheticisation of war that no living person possesses.

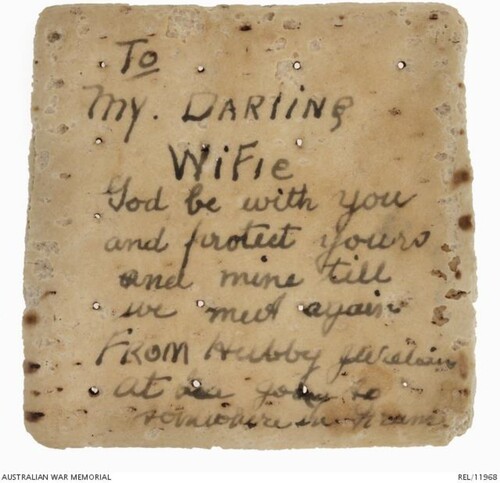

On 10 February 1917, 33-year-old James Williams boarded the SS Osterley in Sydney, Australia, ready to embark on a two-month voyage to Plymouth, England.Footnote1 Williams was a Sergeant in the 22nd Field Artillery Brigade who had enlisted in the Australian Army just four months earlier, following a desperate Government call for more recruits. Sometime into his journey and perhaps missing his family, Williams took a hardtack biscuit from his ration pack – a dense biscuit made from flour, water and salt – and repurposed it into a piece of writing paper. With a black ink pen, he wrote the following letter to his wife ().

FIGURE 1. Hardtack inscribed by Sgt. James William in 1917.

Source: Australian War Memorial, REL/11968.

Then, he turned the biscuit over and added his name, service number and regiment, ready to be sent back home. The abbreviations ‘wifie’ and ‘hubby,’ coupled with the adjective ‘darling’ and the wish for God’s blessing, capture Williams’ affection for his wife, while the vague phrase ‘somewhere in France’Footnote2 highlights the uncertainty and ominousness of his future. Unlike many of his peers, Williams survived the War, having been discharged medically unfit in late 1917 with secondary sarcoma. In 1918, he applied for an army pension, but was rejected as his illness was deemed not a result of war service.

This hardtack is just one of thousands of surviving examples in archival and personal collections throughout the world, which evidence how these food rations were remediatised in creative ways by World War One (WW1) soldiers. As the name suggests, hardtacks were indeed hard and extremely unappetising, with numerous reports of them cracking teeth (Strong Citation2022). They, thus, provided an ideal surface on which to inscribe letters and diary entries, but also to carve into photo frames or objets d’arts. Whether for communicating back home, remembering loved ones or simply relieving boredom in the trenches, hardtacks stand as powerful illustrations of soldiers’ resourcefulness in testing circumstances. They offer an important way to document firsthand WW1 experiences, either as souvenirs of those who survived or as ‘secular relics’ (O’Hagan Citation2023a, 137) for the families of those who sadly never came back.

This study offers the first detailed examination of the materiality of hardtacks, using a small dataset gathered from archival collections in Australia and the United Kingdom. It is specifically concerned with the types of repurposing – or acts of ‘semiotic remediation’ (Prior et al. Citation2006) – that take place, their broader sociocultural functions and the semiotic resources drawn upon to make meaning. The hardtacks are explored from a multimodal ethnohistorical perspective (O’Hagan Citation2022), which embeds social semiotic analysis (Kress and van Leeuwen Citation1996) in archival documents and historical resources both about and from the producers in order to unravel the link between their composition, their owners and the social world. This unique approach offers a clear way to challenge the assertion that social semiotics often derives context from texts without accounting for the broader social practices, processes and people involved in their production or reception (cf. Ledin and Machin Citation2018). In doing so, the study showcases hardtacks as unique items that uncover the ‘semiotic instantiations of lived practices’ (O’Hagan Citation2022), thus revealing how historical artefacts can offer dynamic, contextually emergent, socially constructed knowledges of reality.

As Pauwels and Mannay (Citation2020, 4) note, visual culture is not just about images; it includes ‘visual aspects, objects and “performances” […] which are accessible through direct observation drawing on an array of our senses.’ Consequently, ‘thorough studies of manifestations of visual culture’ must go further than image-based inquiry and encompass three distinctive aspects: (1) production context (i.e. the circumstances in which the text was produced); (2) visual artefact (i.e. analysis of the text’s technology, characteristics, genre and style); and (3) utilisation context (i.e. sociocultural norms, sociopolitical forces and patterned uses and purposes). In the context of this study, this allows for a detailed understanding of how socially constructed knowledge and experiences of WW1 are formed through the hardtack biscuit. Furthermore, considering both the materiality of the hardtack (e.g. its shape, size, texture, colour) and the semiotics of the writing on its surface (e.g. type of writing implement, font, layout, composition, size) facilitates an understanding of writing as a visual phenomenon and recognises its performative nature. While the verbal message itself is important, attention to the visual can also tease out each soldier’s own social goals and the paralinguistic and prosodic features they employ to achieve this, as well as how some typographical choices are guided by social conventions and norms.

Despite their high cultural value and potential for investigation, to date, hardtacks have been surprisingly overlooked in studies of visual and material culture, despite other forms of trench art being the focus of concentrated studies (Saunders Citation2000; Citation2011; Citation2020; Slade Citation2015; Whittingham Citation2008). Instead, they have only been considered in terms of their original function as a food source, whether in WW1 (Beach and Duffett Citation2023; Duffett Citation2008; Citation2012; Citation2017) or earlier conflicts such as the American Civil War (Davis Citation2003; Smith Citation2015), the Spanish-American War (McCaffrey Citation2008) and Anglo-Boer War (Karageorgos and Wood Citation2022; Venter and Wessels Citation2022). Often, such studies have focused on their unappetising taste and texture (Reynaud Citation2020; Richardson Citation2015; Strong Citation2022), how they became a mainstream staple in the early twentieth century (Santlofer Citation2007; Supski Citation2006) and their legacy today in terms of everyday militarism (Kelley Citation2022a; Citation2022b). With the exception of Brown and Cook (Citation2022), the forms and functions of repurposed hardtacks tend only to be mentioned anecdotally in blog posts or popular publications, which frame them as curios and overlook the way that they act as cultural biographies that are central to their owners’ sense of identity and web of memories. As hardtacks are highly fragile artefacts, they are at risk of perishing and, with them, important knowledge of WW1. The timely study of their visual and material features is, therefore, necessary to demonstrate the innovative ways in which soldiers semiotically remediated and recontextualised these artefacts for their own communicative purposes.

WORLD WAR ONE: THE WAR OF VISUAL CULTURE

WW1 is often described as a war of visual culture, with imagery playing a key role in the story of the conflict. The sheer variety of methods, materials and technologies used by both amateurs and professionals to capture the war experience brought about an ‘irreversible sea change in how war could or should be visually recorded and memorialised thenceforward’ (Murray Citation2018, 17).Footnote3

War photography came of age during WW1. Between 1914 and 1918, thousands of photographs were produced by military officials, journalists and amateur photographers for documentary and propagandistic purposes, thereby shaping the war experiences of combatants and civilians (Pichel Citation2021). Photographs were taken of mass mobilisation and military training, hospitals and convalescent homes, everyday life in the trenches and even on the battlefields and frontlines. These were frequently distributed and published in the illustrated press – albeit under military censorship – and offered dramatic and authentic pictorials that made viewers ‘eyewitness[es] of an apparent reality without actually being present’ (Fritz Citation2024). Although prohibited by the authorities, many soldiers carried a Vest Pocket Kodak, which they used to capture their surroundings and help make sense of them. These images were then collected in personal albums or sent back home to loved ones. While photographs were often taken of injuries and disfigurements (cf. Lubin Citation2015), Fritz (Citation2024) notes that death was noticeably absent or only shown abstractly through rituals of remembrance, thus creating a pictorial canon that only ‘marginally corresponded’ to the realities of war.

Posters were another medium that helped shape popular understandings and imaginings of WW1. Used by both the Allies and Central Powers to promote enlistment, sell war bonds and encourage patriotism, posters helped construct ‘a pictorial rhetoric of national identities […] upon which the waging of war hinged’ (Cambria Citation2018, 102). Posters worked effectively because they were cheap and, thus, could be produced at large scale and reach mass numbers of people in every combatant nation. They were also colourful, eye-catching, easy to understand and highly engaging. In James (Citation2009, 2) view, such posters ‘epitomise the modernity’ of WW1 because they served as signs and instruments of the military deployment of modern technology and the development of the home front. Drawing heavily upon discourses of honour, value, nation and family (cf. Cambria Citation2018), they united diverse populations who were all exposed to the same image and, thus, brought together ‘in an imaginary yet powerful way’ (James Citation2009, 2). In a similar vein to posters, caricatures and film reels were also used for propagandistic purposes (cf. Demm Citation1993; Latham Citation2006).

Paintings, sketches and other forms of artwork were also frequently used to visually communicate WW1 experiences. At first, the British government did not support an official war artist scheme. However, they changed their view after several artists who served on the Western Front (e.g. Paul Nash, C.R.W. Nevison) exhibited paintings based on their experiences. Consequently, in 1916, an official war artists scheme was established, first serving a propagandistic function and then later shifting to memorialisation (Fox Citation2013), with commissions by artists such as John Nash, Charles Ernest Butler and Muirhead Bone.Footnote4 Outside of official war artists, there were thousands of amateur artists in the form of soldiers who passed long hours of boredom in the trenches by drawing and painting. Reflective of the restrictions of the frontline, their forms of artwork were often no larger than a postcard and created with ink or pencil, giving them a ‘powerful, authentic simplicity’ (Anderson Citation2018). In contrast to official photographs or posters, the soldiers’ visual responses to WW1 were far darker in tone, capturing the monotony and anxiety of trench warfare and the horror of human sacrifice in a bid to find reason and meaning in the conflict (ibid).

DISOBEDIENT OBJECTS: REPURPOSING THE EVERYDAY IN WORLD WAR ONE

Throughout history, everyday objects have often been repurposed, whether for practical or purposeful reasons. This is particularly the case in times of crisis – i.e. war, famine, poverty or imprisonment – when people make use of the limited resources available to them simply to get by (Auslander and Zahra Citation2018). The International Museum of the Red Cross and Red Crescent in Geneva holds numerous examples of objects practically repurposed by prisoners, such as ashtrays made from powdered milk cans, combs made from food-storage pallets and decks of cards made from toothpaste packaging (Bouvier et al. Citation2019). However, the Museum also demonstrates how such innocuous objects can become ‘disobedient’Footnote5 (Flood and Grindon Citation2014), i.e. transformed for rebellious – and often political – purposes, which seek to disrupt the status quo and make a statement. The repurposing of objects can also have an artistic or creative function, such as the Transforming Arms into Tools project in Mozambique, which has seen over 600,000 weapons used in anti-war art pieces (Tester Citation2006).

In the context of WW1 – the focus of this study – objects could be repurposed for all of the above reasons. In the Imperial War Museum, there are ashtrays, matchbox holders, letter knives, crucifixes, cushions and handkerchiefs created from recycled war materials, such as discarded ammunition shell cases, bullet casings, shrapnel, uniform fragments, pieces of destroyed buildings or downed planes. Typically known as ‘trench art’, these objects were often imbued with morale-boosting messages, political statements or well wishes for loved ones. According to Saunders (Citation2000, 62), they ‘embodied the confusions of war as ambiguous weapons transformed into ambiguous art, each object retaining visual cues to the former lives of its constituent parts.’ Through the aestheticisation of war, these portable pieces played with ‘definitions of materiality and intent,’ redefining social and material worlds as they transformed into ‘whole items of peace’ (ibid). Saunders (Citation2020, 4) emphasises the importance of trench art as a visual reminder of WW1:

They move through symbolic as well as geographical space, intersecting cultural ideas, historical events and personal lives. As they move, in their various guises, they create liaisons between people and places, and punctuate the textual dimension of memory. They also bring to light long-forgotten and sometimes unexpected aspects of the conflict which gave them birth.

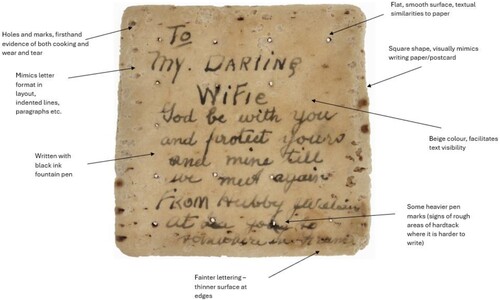

Of particular note is the multimodal nature of hardtacks, where visual meaning is conveyed on multiple levels, as outlined in . There is the materiality of the artefact – its shape, size, texture and colour carry similar affordances to paper and, thus, facilitate writing – but there is also the writing itself. As Lillis (Citation2013, 33) notes, analyses of written language tend to focus on the verbal and, in scant cases when the visual is considered, this is only in terms of spelling and orthography. Adopting a social semiotic approach to typography promotes an understanding of what people do with the visual signs and why, as well as their associated sociocultural meanings (cf. Kress and van Leeuwen Citation1996). In other words, considering the type of writing implement, font, layout, composition, size, provenance and even how texture can affect penmanship emphasises the need to engage with the visual nature of writing. Closely linked to this is the spatial nature of writing, particularly in terms of how writing occupies a space, its sequentiality and how it exists in the same textual area as visual and verbal cues (Lillis Citation2013, 38).

FIGURE 2. The visual aspects of the remediatised hardtack biscuit.

Source: Australian War Memorial, REL/11968.

Speaking about the close association between cultural memory and the arts, Assmann (Citation1999, 215) notes that the visual ‘fits into the landscape of the unconscious in a way that is different from texts,’ taking on a life of its own and changing from ‘an object of observation’ into ‘an agent of haunting.’ This is particularly relevant to the context of WW1 and hardtack biscuits, many of which now survive in museums and archives and act like ‘materialised secrets’ or ‘dead letters of the object world’ (O’Hagan Citation2023a, 131) waiting to be reactivated and their stories reconstructed.

RESEARCH DESIGN

This study investigates a dataset of 35 repurposed WW1 hardtacks. Almost half of the collected sample comes from the Australian War Memorial in Canberra, which contains an extensive archive of WW1 military records, photographs, heraldry and technology. The other examples come largely from the Imperial War Museum, National Army Museum and Reading Museum in the United Kingdom. The remaining examples were collected from local museums scattered around the country. provides a summary of these data collection sources.

TABLE 1. Summary of data collection sources.

While various forms of hardtack biscuit have existed since ancient times (e.g. dhourra cake in Ancient Egypt, bucellatum in Ancient Rome), they first became standard military and navy rations in the seventeenth century (Cook Citation2004). Being both inexpensive and long-lasting, hardtacks provided ideal sustenance for long sea voyages and military campaigns. During WW1, in Australia, hardtacks were produced under government contract by Swallow & Ariell – the country’s first and largest biscuit manufacturer – while in the United Kingdom, it was Huntley & Palmers – the world’s largest biscuit manufacturer – who was responsible for their production. The majority of hardtacks in the collected dataset come from these two manufacturers.

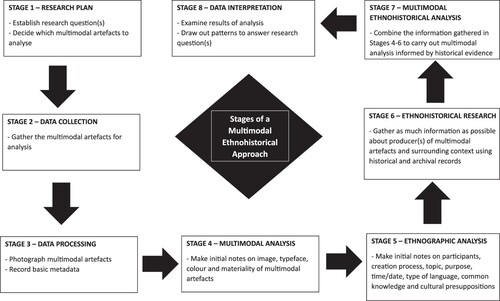

The hardtacks were subjected to a detailed multimodal ethnohistorical analysis outlined in (cf. O’Hagan Citation2022). After the initial data collection and processing stages, visual social semiotic analysis (Kress and van Leeuwen Citation1996) was applied to explore the semiotic and material features of the hardtacks. Visual social semiotics sees sign-making as a social process and semiotic resources (e.g. image, colour, typography, texture, layout, composition) as socially shaped over time to become meaning-making resources that articulate specific ideas, values or identities demanded by the requirements of a person or community. These resources have meaning potentials – defined as the affordances or constraints of modes – which are deeply embedded in existing sociocultural norms and sociohistorical settings (Machin and Mayr Citation2012, 4). Following this stage, ethnographic analysis – specifically drawing on the sociolinguistics of writing (Lillis Citation2013) – was used to focus on the materiality of any written language on the hardtacks and conduct socially-oriented textual analysis. Then, ethnohistorical research was carried out to gather firsthand information on the creators from archival records. For this purpose, the military records held at the National Archives of Australia and the National Archives in the United Kingdom were accessed online, along with pertinent census records available on Ancestry and the data collection sources’ own catalogue descriptions. Together, these three foci – multimodal, ethnographic and ethnohistorical – enabled a comprehensive overview of the forms and functions of the repurposed hardtacks.

Essential to my analysis is the concept of ‘semiotic remediation’ (Prior et al. Citation2006), which is concerned with how a text builds on another text in terms of its materiality, practices or conventions, thereby recontextualising and remediating the text’s traces in its new context (Ferris and Banda Citation2018). According to Hengst and Prior (Citation2010:, 1), semiotic remediation entails ‘taking up the materials at hand, putting them to present use, and thereby producing altered conditions for future action.’ When it comes to remediation as repurposing, Bolter and Grusin (Citation2000) outline two key strands: (1) transforming a familiar content into another media form (e.g. a comic book series becomes a live-action movie) and (2) creatively refashioning materials and practices and/or appropriating and transforming materials and techniques with new meanings and purposes. With its focus on the materiality of hardtacks, the current study is concerned with the latter.

Banda and Jimaima (Citation2014) note how early studies on remediation were focused predominantly on mediated discourse, particularly in the context of new media (cf. Hengst and Prior Citation2010 for a comprehensive overview), but that the growth of research on semiotic landscapes has helped extend the concept to the physical (cf. Stroud and Jegels Citation2014; Thurlow and Jaworski Citation2014). Repurposing in this way underlines ‘the agentive nature of human-sign-environment interaction’ (Banda and Jimaima Citation2014, 645), thereby capturing ever-emergent social relations, as well as the ways that new purposes and meanings can become infused into semiotic materials. When applied to the study of hardtacks, this approach recognises ‘the simultaneous, layered deployment of multiple semiotics’ (Hengst and Prior Citation2010, 19) in the artefacts and how they embody new activities and sociocultural experiences in an individual’s life. Production and consumption, thus, become ‘dialogic’ and ‘drawn from a history of sign use’ (ibid:7) that builds upon the present interaction to help (re)shape future responses and acts.

ANALYSIS

Following the process outlined in , I identified five types of remediation in the dataset of hardtacks: declarations of ownership; letters; diary entries; photo frames; and objets d’art. shows each type alongside its respective quantity. The hardtacks bear dates from the entire duration of the war – 1914–1918 – with only 7 undated. They were inscribed all over the world, from training grounds and camps in the United Kingdom and Australia, at sea, on the Western Front in France, at Gallipoli in Turkey, and even as far afield as Delhi in India and Papua New Guinea. A range of writing implements were used to mark the hardtacks, including plain lead pencils, indelible pencils, black ink pens, blue ink pens and paints, while multiple other semiotic resources were drawn upon in the act of remediation, such as thread, luggage tags, glazed cases, wooden frames, metal tins, postal stamps and censor stamps. In what follows, I use multimodal ethnohistorical analysis to focus on the five types in turn, drawing on prototypical examples from the dataset to discuss their forms and functions. Overall, I demonstrate how hardtacks embody unique, individualised experiences of war, providing a glimpse of humanity at a time of harrowing conflict.

TABLE 2. Types of remediation.

Hardtacks as Declarations of Ownership

Perhaps the simplest way that hardtacks were repurposed was through ownership inscriptions that marked the soldier’s name and/or regiment, date and/or location. However, simple by no means signified banal. As Rose (Citation1994, 16) notes, ownership is a culturally and historically specific system of communication through which people act and negotiate social, economic and political relations. Owning an item fosters a sense of identity and rootedness in the world and allows people to construct a relationship between themselves, others and the finite world of time and space (O’Hagan Citation2021, 24). Ownership became particularly important in wartime when people lived in shared spaces, had few truly personal possessions and items could be easily mislaid or stolen. Inscribing a name was, thus, a clear way to convince others of ownership and offered a means for coming to terms with one’s own identity in an unstable society.

As the ownership inscription required relatively few resources or knowledge to create, it was available to everyone. Nonetheless, such declarations of ownership on hardtacks should not just be viewed as a primary impulse or proprietary instinct to claim an object as one’s own; they also served as a registry of human encounters, mirrors through which soldiers observed their own lives. Unlike declarations of ownership on the endpapers of books, which are typically individual, hardtack inscriptions were frequently collective, marked by a person’s regiment rather than their name. This inscriptive act signifies the importance of a collective identity and the sense of camaraderie on the frontline. However, this collective identity could also risk playing down individual war experiences and reducing personal agency, demonstrating the eschewing of one’s own personal identity to become a militarised conglomerate defined by profession.

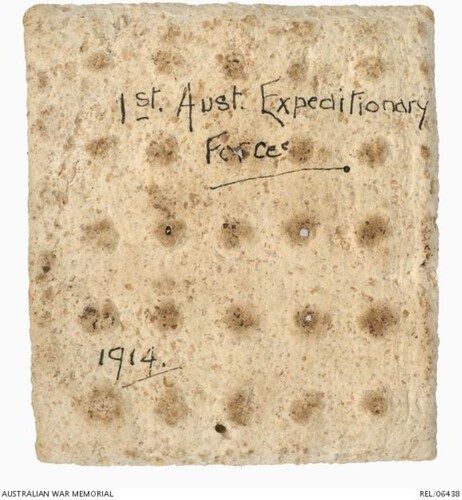

A case in point is , marked ‘1st Aust Expeditionary Force 1914’ in black ink by an anonymous individual. The regiment name and date are both underlined, accentuating their importance, while some letters are distorted by the hardtack’s holes (e.g. the ‘r’ and ‘s’ in ‘forces’). The inscription clearly served multiple functions: an innate instinct to mark possession, but also a declaration of brotherhood and shared experiences. It, thus, indicates, how such declarations of ownership on hardtacks are deeply entwined with a broader cultural code of asserting and contesting rights, negotiating identity and mediating relationships with others.

Hardtacks as Letters

Hardtacks were frequently repurposed as letters. Their blank surface, hard texture, and square or rectangular shape facilitated this remediation, mimicking the material properties of the picture postcard – an ubiquitous writing technology of the early twentieth century (Gillen Citation2023). The picture postcard was used across all class groups in British society, but was a particular boon for the working classes as it enabled the exchange of rapid, cheap, accessible written messages without the need for more formal – and more time-consuming – letter-writing conventions. Many lower-rank soldiers, thus, drew upon the similar affordances of the hardtack, using its small space to write short messages back home. Being an essential part of soldiers’ ration packs, the hardtack was convenient, always available to write on hurriedly in the absence of paper and frequently used as a stopgap between longer letters to let loved ones know that they were well.

Even in hardtack form, soldiers abided with the standard formats of postcards, replicating their conventions in terms of layout and composition (cf. O’Hagan Citation2021 for similar findings with book inscriptions). Typically, one side of the biscuit was used for the recipient’s name and address, while the other was reserved for the letter. In most cases, the letter started with the date and location, followed by a greeting (e.g. Dear Nell) and ended with a typical sign-off (e.g. From Dad xx). When soldiers instead used both sides of the biscuit for their letter, they found resourceful ways of adding the recipient’s name and address. In some cases, they took advantage of the hardtack’s small holes to sew a running stitch and attach a luggage tag to the end, while in others, they put the hardtack in an empty tin and stuck a label to its lid. Families, in turn, found resourceful ways to keep the hardtack as a souvenir, often displaying it in its own photo frame as a material ‘stand-in’ (O’Hagan Citation2023a, 145) for their absent loved one. The postal stamps and ‘passed by censor’ rubber stamps on the hardtacks added another layer of meaning, demonstrating how an army-issued food (re)negotiated officialdom in its new form.

In accordance with other studies on more conventional WW1 letters (cf. Hanna Citation2003; Helmers Citation2016; Ulrich and Ziemann Citation2010), the topics of the hardtack letters tend to be relatively mundane, given that censorship prevented soldiers from revealing the horrors of war to loved ones. However, as Hanna (Citation2004) argues, this mundaneness should by no means be equated to insignificance because it provides vital evidence of how soldiers remained connected psychologically and emotionally to their families. In her study of early twentieth-century picture postcards, Gillen (Citation2023, 126) found that most writers used postcards to ‘make plans and give accounts,’ as well as send well wishes on special occasions, using language that was inextricably associated with personal relationships and the performance of identity. Such functions are also clear in hardtack letters, where writers frequently sent formulaic messages of love and affection to their families:

‘Wishing you all a merry Christmas and a happy new year’

‘God be with you and protect yours and mine till we meet again’

‘Merry Christmas and a prosperous new year, from Old Friends’

Overwhelmingly, however, hardtacks served a dual function of letter and prop, sent back home deliberately as firsthand evidence of the poor quality of food rations. More than half of all collected hardtack letters explicitly critique the biscuit, often using humour as a mitigating device. ‘Your King and your Country need you and this is how they feed you’ is a frequently reoccurring rhyme, emphasising how such messages became widely dispersed and culturally embedded in army discourse as hardtacks were circulated among soldiers and their families (cf. O’Hagan Citation2020 for similar findings with book curses). Others provide sarcastic remarks like ‘Have gone on hunger strike, reason attached, mind your toes!’ and ‘How would this do for standing the iron on?’ in reference to the hardtack’s rigidity and unappetising taste and appearance, while others still simply offer short factual statements (e.g. ‘what soldiers live on,’ ‘Sunday’s tea’). In some cases, recipients have added their own comments to the hardtack, as exemplified by the mother of Bombardier Fred Kerr of the Royal Field Artillery who wrote ‘half of his breakfast’ on the hardtack sent by him on 30 April 1916.

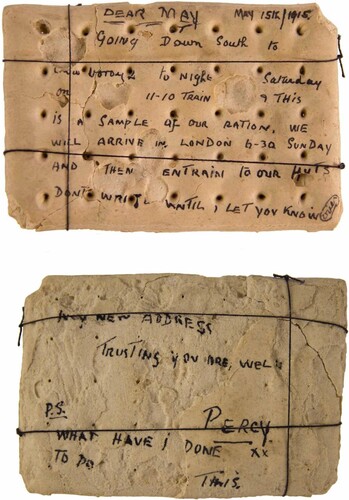

shows a hardtack letter written by 18-year-old Sergeant Percy Lockett of the Manchester Regiment to his sister May in May 1915. Lockett informs May that he is ‘going down south’ and will ‘arrive in London 6.30 Sunday.’ Making an explicit deictic reference to the hardtack, he also informs May that ‘this is a sample of our ration.’ The letter is written with a black ink pen and shows blotting in places (e.g. the ‘T’ of ‘write’), as well as illegible words due to the worn surface. The letter continues onto the other side of the hardtack, where Lockett asks after May’s health and signs off (Percy xx), He then adds an emotional PS: ‘what have I done to deserve this?’ The ‘deserve’ has clearly been removed, perhaps standing as evidence of censorship by the War Office or simply wear and tear. May’s address is attached to the hardtack with black thread. Lockett’s ultimate destination was Gallipoli in modern-day Turkey and later Egypt, the Western Front and Belgium. In February 1918, he was awarded a Military Medal for devotion to duty while repairing a dam broken by enemy shell fire. Lockett survived the war and returned to Manchester, marrying Mabel Annie Holt in 1921. Their only child, Norman, was born in 1923. Lockett went on to serve in the Cheshire Special Constabulary until his death in 1952 aged 56.Footnote7

Hardtacks as Diary Entries

In times of hardship and crisis, diaries can offer an outlet for people to try and bring order to the chaos by unburdening their fears and frustrations. Noting down personal experiences and observations serves as an act of self-reflection, facilitating a form of ‘verbalised solipsism’ (O’Hagan Citation2021, 239), where writers constantly reshape and revise their self or selves. Perhaps unsurprisingly, WW1 sparked a boom in diary writing amongst soldiers, easing boredom in the trenches, but more importantly, helping them make sense of war and providing a rare opportunity to reevaluate their newly militarised identities (Martin Citation2017). While many recorded their experiences in notepads and on sheets of paper, others made use of whatever resources they could acquire, from scraps of material to hardtacks. Through these entries – often focusing on the immediate present and written in a serial, open-ended format – it is possible to trace the everyday realities of warfare and the complex ways that war writing can turn into life writing.

Spijkerman, Luminet, and Vrints (Citation2018) have found that most WW1 diary entries were highly concerned with noting precise dates and locations. As warfare disturbed existing notions of place and time, recording such information enabled soldiers to feel in control of a situation in which they, in fact, had very little control. This is apparent in the collected hardtacks, where writers pay great attention to situating themselves geographically and temporally (e.g. ‘Engineers Camp – Seymour. April 2nd to 24th 1917’). Through such markers, writers could give structure to the disorienting absence of structure of their daily lives. It also enabled them to construct a private discursive place in which they could define their position in relation to others and the world around them. In some cases, the hardtack itself served as the reason for soldiers’ diary entries, written on to document the biscuit as a standard army food ration (e.g. ‘Army biscuit served to the British troops with rations during the great European War Aug 1914’). Here, both the writing and the material itself were important, enabling soldiers to return to the hardtack at a later date – perhaps post-war – in order to ‘tour the picturesque ruins of their former self’ (O’Hagan Citation2021, 240) and their previous experiences.

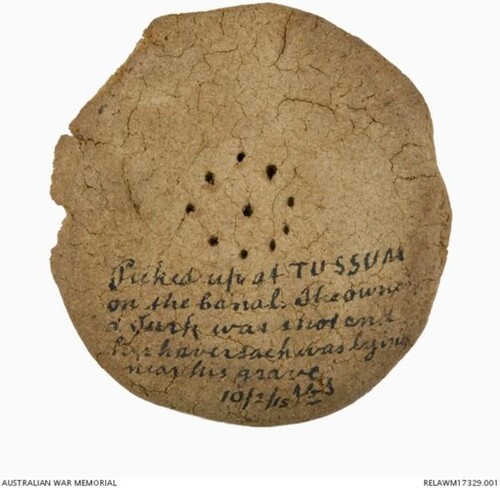

According to Spijkerman, Luminet, and Vrints (Citation2018), WW1 diary entries could also serve as coping mechanisms, whether by confronting or avoiding events so as to control, tolerate or decrease their impact. Documenting an event made it permanent through writing, thereby turning the diary into a ‘place of asylum’ (ibid) that writers could revisit in future to gain clarity in mind from subsequent readings. In revisiting the text, writers could also purge feelings that they no longer considered relevant – an act that Lejeune (Citation1989, 194) refers to as ‘a sort of spring-cleaning, after which you set out again, lighter.’ However, often these events were written with black humour or a form of detachment (i.e. emotion-charged language was replaced with facts) in order to mitigate their psychological impact. This is apparent in the hardtack dataset, perhaps best exemplified by .

FIGURE 6. Hardtack as diary entry, created by Captain James Campbell Stewart, 1915.

Source: Australian War Memorial, REL/11968.

This hardtack was inscribed on 10 February 1915 by Captain James Campbell Stewart of the 5th Battalion, Australian Imperial Force. He notes that the biscuit was:

Picked up at TUSSUM on the Canal. The owner a Turk was shot and his haversack was lying near his grave

Hardtacks as Photo Frames

In his study of trench art, Saunders (Citation2020) notes that many soldiers made use of scrap metal, bullet cartridges and souvenired glass to create their own photo frames. These frames represented ‘worlds within worlds’ (ibid, 82), incorporated into trench life yet keeping the photographed subject(s) apart. Hardtack biscuits could also be used in a similar way, repurposed into photo frames that served as triggers for memories of ‘another place and time separated by geographical and symbolic space’ (ibid). These frames can be seen as forms of ‘expressionistic destruction’ (Björkvall and Archer Citation2021) in that the soldier’s own emotions and feelings played a central role in the altering and restructuring of the hardtack’s original purpose as a food ration. This imbued the hardtack with a symbolic value, transforming it in ways that were meaningful to soldiers’ own lives; in this case, as vehicles of memory and an identity outside of soldierhood.

Just as the hardtack’s properties facilitated its transformation into a letter, so they also aided its reconfiguration as a photo frame. The shape of the biscuit bore a striking similarity to the shape of a typical photo frame, while its straight edges provided a clear border. Its thin surface also made it easy to scrape away the centre and scoop out a hollow, whether using utensils, writing implements, tools or weapons. This hollow then provided an ideal space to slot a photograph. Like with the letters, soldiers took advantage of the biscuit’s holes, often sewing thread through the top of the hardtack to create a hook, which then enabled the frame to be hung up in the trenches. Saunders’ (Citation2020) book on trench art includes a rare firsthand account by Lance Corporal Reginal Bunn of how he made a photo frame in the trenches using scrap metal. He describes the ‘crude workmanship […] made under circumstances over which [he] had no control’ (ibid:73) using whatever materials he had to hand. This account captures the combination of spontaneity, opportunism and logic that soldiers drew upon when repurposing everyday objects of war, including hardtacks, to maintain connections with those back home.

Perhaps as to be expected, the most common photographs to be displayed in hardtack frames were of loved ones, particularly wives or girlfriends, children, parents and siblings. Such photographs worked as aides-mémoires, offering soldiers a visual reminder of their families and, thus, a form of moral support. However, as Saunders (Citation2020, 82) notes, there was also a certain irony in the fact that the materials from which the frames were made and which protected the image also represented the very thing separating the soldier from the person in the image (i.e. war). Some soldiers also used their frames to display photos of their battalion. WW1 was the first conflict to be photographed in detail, with many soldiers bringing their own cameras to document their travels and experiences (Beurier Citation2004). Capturing photos of fellow comrades not only acted as a way to boost morale and keep one’s eye on the goal, but it also served as a form of remembrance of the fallen. Famous military figures like Lord Kitchener could also be found in photo frames, acting as a symbol of respect and national identity, while also reminding soldiers of their sense of duty.

Some hardtack frames were inscribed and sent back home to loved ones, with photos of the soldier in uniform displayed in the centre. These hardtacks would then be placed into a wooden photo frame and hung up on the wall or placed on a mantelpiece. According to Callister (Citation2007, 663), such photos were ‘invested with unforeseen emotional meanings.’ While they offered families a souvenir of their loved one, a chance to look at their face despite the distance and time keeping them apart, they could also take on more poignant meanings should anything happen to that soldier. Thus, they could also become ‘referents for absent bodies and as artefacts of mourning and memory’ (ibid).

shows a hardtack photo frame made by Rifleman George Mansfield of the 2/21st London Regiment in 1917. He served in Palestine and, later, on the Western Front. Mansfield carved a heart shape into the centre of his hardtack and placed a portrait of himself inside. A sense of the arduous labour that Mansfield underwent in creating the heart-shaped hollow is captured in the rough edges around the photograph and the hardtack crumbs still attached to its surface. Mansfield sent the framed photograph home to his mother as a message of reassurance that he was well. She subsequently placed the biscuit into a glazed case and added a hook to display it, thereby adding another layer of meaning to the item. Such acts enabled women like Mrs Mansfield to participate in their son’s war experience in a small way, but could also lead to feelings of helplessness. Thankfully, Mansfield survived the war and went on to work in the cloth trade in London.Footnote9

Hardtacks as Objets d’art

Strongly linked to their repurposing as photo frames, hardtacks could also be transformed into objets d’art – small decorative or artistic objects. As Saunders (Citation2020) notes, WW1 was recognised at the time as a war of matériel or Material-schlacht. Trench art played a key role in this, occupying a ‘dynamic point of interplay’ (1) between animate and inanimate worlds and encouraging a gaze beyond the physicality of objects to the hybrid and constantly renegotiated relationships between such objects and people. Trench art was often created as a means of escapism and to combat boredom, but could also be a way of restoring order and purpose to a soldier’s tumultuous life.

The ways in which hardtacks were creatively transformed for artistic purposes showcases the personal and idiosyncratic interpretations of war as physical objects directly associated with conflict were manipulated and imbued with new symbolic meanings. Hardtacks were frequently painted upon with images of entwined flags, interlocking hands, flowers and horseshoes, all serving to indicate conviviality, solidarity and positivity in the face of adversity. Others featured detailed drawings of picturesque landscapes far from the realities of warfare, perhaps conjuring up memories of a distant past or an imagined future. They could also be emblazoned with mottos and inspiring quotes, or elaborated by sewed-on artillery shells or reshaped and cut to represent medals.

In many cases, these items were taken home after the war by soldiers and displayed in the domestic setting as souvenirs, thereby reclaimed for domestic remembrance and transformed into a ‘comfortable aspect of daily life’ (Whittingham Citation2008, 114). In this way, the hardtacks became ‘relics and intermediaries between the visible and invisible world of experience and death’ (ibid:115), bridging the gap between everyday life and events from a chaotic past. Following the war, they also played an important role in shaping the culture of public remembrance, often displayed in museums and churches as signs of the fallen.

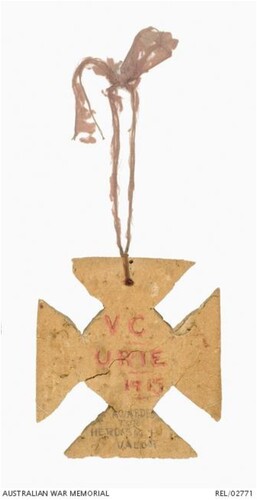

A particularly striking example of how trench art aestheticised reality and offered a permanent memory of wartime experience can be seen in . It shows a hardtack expertly cut into the shape of a Maltese cross and suspended from a piece of ribbon. The Maltese cross would have been instantly recognisable to soldiers and loved ones back home as the shape of the Victoria Cross – the highest and most prestigious decoration of the British honours system, awarded to members of the British Armed Forces for valour ‘in the presence of the enemy.’ Here, the creator, V.C. Urie, engages in a cheeky act of rebellion, pastiching the prestigious medal and awarding the hardtack medal to himself for ‘heroism and valour.’ Drawing upon shared knowledge of wartime experiences, Urie implies that the hardtack is so inedible that he deserves a medal for being brave enough to eat it – a joke that would have been well appreciated by his fellow comrades. Despite the trying circumstances of war, humour was, in fact, a frequent part of daily life. As Madigan (Citation2013) notes, a robust rejection of victimhood and an emphasis on perseverance was often articulately expressed through humour. The hardtack, thus, serves as a form of ‘expressionistic destruction’ (Björkvall and Archer Citation2021), with Urie ‘destroying’ the object’s original intention and ‘value adding’ through his own repurposing. Urie’s name and date are written in the centre of the cross in black ink and then overlayed with red crayon to accentuate the words. The reason for award is written in lead pencil at the bottom of the cross, the capital letters tightly compacted together to fit into the small space. Private Urie enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force in 1915 at 18 years old. He served in France with the 16th Field Ambulance and the 5th Field Ambulance, surviving the war and returning home on the SS Armagh in 1919.Footnote10

CONCLUSION

Hardtack biscuits provide an untapped resource for understanding the materiality of WW1. Issued as food rations by the army but frequently repurposed by soldiers for a range of communicative intentions, they offer a unique and unmediated way to document WW1 experiences. This paper has offered a first attempt to understand the forms and functions of these repurposed hardtacks using a unique combination of multimodal and archival research. It has found that soldiers often drew upon the affordances of the hardtack, viewing its hard surface as a ‘blank canvas’ on which to write letters back home, record diary entries or mark declarations of ownership. Equally, soldiers gave hardtacks new leases of life as photo frames or objet d’arts, channelling their emotions into the creation of new decorative objects for themselves or to send to loved ones – what Björkvall and Archer (Citation2021) see as forms of ‘expressionistic destruction.’ Creating these objects not only eased boredom in the trenches, but also gave them a touch of domestic normality, transforming items associated with warfare into innocuous items of peace.

While most soldiers used ink pens or indelible pencils to inscribe their hardtacks, they also found other resourceful ways to individualise them, drawing upon other implements and materials in their possession, such as paints, threads, luggage labels, glazed cases, metal tins and wooden frames. The idiosyncrasies and imperfections of each hardtack, thus, imbues them with an emotional immediacy not felt when just reading a soldier’s name in an official record, demonstrating their important role as ‘psychological visiting cards’ (O’Hagan Citation2023a, 152) that indicate hidden aspects of a person’s wartime experiences. Letters and diary entries on hardtacks gave soldiers an opportunity to make sense of their everyday lives and navigate the different aspects of their self (i.e. their identities back home and as a soldier). Their writings typically document events with precise dates and locations, but they are also peppered with more banal comments about the weather or expressions of longing for home. Above all else, however, is an overwhelming focus on the poor quality of food, the physicality of the hardtack serving as first-hand evidence of this. Across all forms of semiotic remediation, humour – perhaps surprisingly – is highly apparent, clearly used by soldiers as a coping mechanism and a form of detachment from the harrowing scenes around them.

Beyond the actual messages inscribed into the hardtacks, a multimodal ethnohistorical perspective draws attention to both the materiality of the biscuit and the visual nature of the writing inscribed on its surface. First, the type of writing implement used provides details of technological development and the availability of resources to soldiers, indicating that choice was predominantly motivated by practical factors like availability and durability over symbolic meanings (O’Hagan Citation2021, 168). Second, the differences in thickness and weight of pen strokes show subtle differences in the material construction of the hardtack and visible signs of wear and tear. Third, soldiers’ use of underlining or capitals indicate salience, underscoring topics that they considered particularly important, while layout was largely influenced by conventions carried over from letter – and postcard-writing, although space could also be used performatively, particularly when cut into certain shapes (e.g. a photo frame or medal; string weaved through holes to make sections). Hardtacks could also provide evidence of how some letters were subject to censorship, with certain words scraped off in a bid to maintain morale (e.g. ‘deserved’ in Percy’s statement ‘what have I done to deserve this?’). The hardtacks also reveal an interesting space where the official and unofficial meet, as apparent through the embossed Huntley & Palmer’s brand name as a backdrop to Rifleman George Mansfield’s photograph. This emphasises the disruption of the hardtack’s primary purpose (i.e. as a food ration) and its subversion as a material object with a new sociocultural function.

Post-war, the hardtacks also served an important function as objects of memorialisation. For those who survived and returned home, the hardtacks stood as mementos of life at the front, yet, as Whittingham (Citation2008, 97) notes, the placement of war souvenirs in the civilian home could be ‘disconcerting’ for soldiers. For those who did not survive, their hardtacks acquired new simultaneous functions as memento mori, secular relics and mourning artefacts, carrying an aura that embodied the deceased and, thus, helped the bereaved cope with their loss, especially in the absence of a body (cf. O’Hagan Citation2023a). In these cases, the hardtacks acted as a meeting point between life and death, materiality and selfhood, body and personality, thereby acquiring symbolic meanings disproportionate to their everyday value. Such hardtacks also played a key role in the culture of public remembrance, often displayed in museums or churches or even sold in shops following a fad for selling WW1 souvenirs.

Overall, in their singular ability to provide novel accounts of WW1 experiences, hardtacks are an important resource that should be given just as much value as forms of trench art made from munitions and other war detritus. Reconstructing the stories behind these repurposed objects can help gain a better sense of the aestheticisation of war and the different ways that soldiers on the frontline coped in WW1 and tried to maintain connections with loved ones back home. They, thus, stand as a testimony to the resourcefulness of humans in testing circumstances. Studying these unique objects emphasises why visual culture studies must extend beyond image-based inquiries and consider the materiality of objects and their semiotic resources (e.g. typography, colour, texture), as well as the broader sociocultural and historical circumstances that constitute their construction (cf. Pauwels and Mannay Citation2020, 4). In the context of the current study, this approach has facilitated a better understanding of everyday life in WW1 and how individuals modified functional items and imbued them with new communicative purposes. This is even more important today when there are no more people alive who lived through the conflict. These hardtacks, therefore, hold a wealth of knowledge about WW1 that no living person possesses. For this reason, it is important to preserve and conduct further research on surviving examples in both private and public collections in order to keep these individuals’ voices and stories alive.

From a theoretical and methodological perspective, the study has also demonstrated the benefits of combining multimodal semiotics and historical ethnography. Drawing on archival resources helps to ground multimodal analyses in concrete evidence rather than relying on subjective judgements or narrow focuses restricted by the descriptive labels and rules of visual grammar (O’Hagan Citation2023b). Furthermore, anchoring communicative practices in the systems and institutions of the social world uncovers the connections between specific semiotic choices, meaning-making practices and their sociocultural effects. This, in turn, enables the accurate reconstruction of cultural practices, leading to a better understanding of the complexities of historical events (in this case, WW1) and a recognition that semiotic choices are embedded in individual experiences and attitudes, as well as socially situated activities and traditions. It is hoped that the results fostered by this approach in the context of WW1 hardtacks will encourage other scholars to apply multimodal ethnohistory to visual objects or, at the very least, use the approach to challenge the supposed novelty of contemporary multimodal texts and situate them within a broader tradition of sociocultural practices, sociopolitical forces and patterned uses.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Lauren Alex O’Hagan

Lauren Alex O’Hagan is a Research Fellow in the School of Languages and Applied Linguistics at the Open University and an Affiliated Researcher in the Department of Media and Communication Studies at Örebro University. She specialises in performances of social class and power mediation in the late 19th and early 20th century through visual and material artefacts, using a methodology that blends social semiotic analysis with archival research. She has published extensively on the sociocultural forms and functions of book inscriptions, food advertisements, postcards, and writing implements.

Notes

1 James Williams’ army records are available via the National Archives of Australia (https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Gallery151/dist/JGalleryViewer.aspx?B=1808694&S=1&N=41&R=0#/SearchNRetrieve/NAAMedia/ShowImage.aspx?B=1808694&T=P&S=4).

2 Although Williams states in his letter that he is on his way to France, the army records show that his destination was, in fact, Plymouth in England, demonstrating the unpredictable future that awaited many soldiers posted overseas.

3 Although outside of scope here, other significant visual artefacts associated with post-WW1 memorialisation are war memorials and cenotaphs (cf. Machin Citation2014).

4 Similar schemes were established in the US and Australia.

5 ‘Disobedient Objects’ was, in fact, the name of a 2014–15 exhibition at the V&A Museum, which sought to examine the powerful role of objects in movements for social change.

6 ‘God punish Germany’ – a play on the anti-British slogan ‘Gott strafe England’ used by the German Army during World War I.

7 All details on Lockett have been gathered from census and military records on www.ancestry.com and the catalogue description of the hardtack in the Museum of the Manchester Regiment.

8 All details on Campbell Stewart have been gathered from census and military records on www.ancestry.com and the catalogue description of the hardtack in Reading Museum.

9 All details on Mansfield have been gathered from census and military records on www.ancestry.com and the catalogue description of the hardtack in Reading Museum.

10 All details on Urie have been gathered from census and military records on www.ancestry.com and the catalogue description of the hardtack in the Museum of the Manchester Regiment.

References

- Anderson, S. M. 2018. The Art the Soldiers Made During the First World War. Museum Crush (18 September), https://museumcrush.org/the-art-the-soldiers-made-during-the-first-world-war/ (Accessed: 4 April 2024).

- Assmann, A. 1999. Cultural Memory and Western Civilisation: Arts of Memory. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Auslander, L., and T. Zahra. 2018. Objects of War: The Material Culture of Conflict and Displacement. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Banda, F., and H. Jimaima. 2014. “The Semiotic Ecology of Linguistic Landscapes in Rural Zambia.” Journal of Sociolinguistics 19 (5): 643–670. https://doi.org/10.1111/josl.12157.

- Beach, J., and R. Duffett. 2023. “Tommies, Food, and Drink: A Microhistory, 1914-18.” Journal of War & Culture Studies 16: 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/17526272.2021.1879455.

- Beurier, J. 2004. “Death and Material Culture: The Case of Pictures During the First World War.” In Matters of Conflict: Material Culture, Memory and the First World War, edited by N. J. Saunders, 109–123. London: Routledge.

- Björkvall, A., and A. Archer. 2021. “Semiotics of Destruction: Traces on the Environment.” Visual Communication 21 (2): 218–236. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470357220957375.

- Bolter, J. D., and R. Grusin. 2000. Remediation: Understanding New Media. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Bouvier, P., R. Mayou, M. Rueff, and I. Schulte-Tenkhoff. 2019. Prisoners’ Objects: The Collection of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Museum. Milan: 5 Continents Editions.

- Brown, L., and T. Cook. 2022. “The Lives and Afterlives of Material Culture: New First World War Artifacts at the Canadian War Museum.” Canadian Military History 31 (2): 1–46.

- Callister, S. 2007. “Picturing Loss: Family, Photographs and the Great War.” The Round Table 96 (393): 663–678. https://doi.org/10.1080/00358530701634242.

- Cambria, M. 2018. “Naming the Unnamable: The Pre-Texts of WW1 Posters.” In Un-representing the Great War: New Approaches to the Centenary, edited by M. Cambria, G. Gregorio, and C. Resta, 97–113. Newcastle Upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars.

- Cook, A. 2004. “Sailing on The Ship: Re-enactment and the Quest for Popular History.” History Workshop Journal 57: 247–255. https://doi.org/10.1093/hwj/57.1.247.

- Davis, W. C. 2003. A Taste for War: The Culinary History of the Blue and the Gray. Mechanicsburg: Stackpole Books.

- Demm, E. 1993. “Propaganda and Caricature in the First World War.” Journal of Contemporary History 28 (1): 163–192. https://doi.org/10.1177/002200949302800109.

- Duffett, R. 2008. “A War Unimagined: Food and the Rank and File Soldier of the First World War.” In British Popular Culture and the First World War, edited by J. Meyer, 47–70. Leiden: BRILL.

- Duffett, R. 2012. “A Taste of Amy Life: Food, Identity and the Rankers of the First World War.” Cultural and Social History 9 (2): 251–269. https://doi.org/10.2752/147800412X13270753068885.

- Duffett, R. 2017. “Indigestion and Digestion on the Western Front in Saunders N.J.” In Modern Conflict and the Senses, edited by P. Cornish, 171–183. London: Routledge.

- Ferris, F., and F. Banda. 2018. “Recontextualisation and Reappropriation of Social and Political Discourses in Toilet Graffiti at the University of the Western Cape.” Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics Plus 55: 27–45. https://doi.org/10.5842/55-0-778, https://www.ajol.info/index.php/splp/article/view/184485.

- Flood, G., and C. Grindon. 2014. Disobedient Objects. London: V&A Publishing.

- Fox, J. 2013. “Conflict and Consolation: British Art and the First World War, 1914–1919.” Art History 36 (4): 810–833. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8365.12033.

- Fritz, J. 2024. The Canon of Images of the First World War as Reflected in the Illustrated Press, https://ww1.habsburger.net/en/chapters/canon-images-first-world-war-reflected-illustrated-press (Accessed: 4 April 2024).

- Gillen, J. 2023. The Edwardian Picture Postcard as a Communications Revolution: A Literacy Studies Perspective. New York: Routledge.

- Goffman, E. 1981. Forms of Talk. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Hanna, M. 2003. “A Republic of Letters: The Epistolary Tradition in France During World War I.” The American Historical Review 108 (5): 1338–1361. https://doi.org/10.1086/529969.

- Hanna, M. 2004. “War Letters: Communication Between Front and Home Front.” In International Encyclopedia of the First World War, edited by Oliver Janz, 1–14. Berlin: Freie Universität Berlin. https://revfrankhughesjr.org/images/_War_Letters_Communication_between_Front_and_Home_Front.pdf (accessed 21 November 2023).

- Helmers, M. 2016. “Out of the Trenches: The Rhetoric of Letters from the Western Front.” In Languages and the First World War: Representation and Memory, edited by Christophe Declercq, and Julian Walker, 54–72. London: Palgrave-Macmillan.

- Hengst, J. A., and P. A. Prior, eds. 2010. Exploring Semiotic Remediation as Discourse Practice. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- James, P. 2009. Picture This: World War I Posters and Visual Culture. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Karageorgos, E., and B. Wood. 2022. “Health and Fitness of the Queensland Contingents to the South African War, 1899–1902.” Health and History 24 (1): 25–46. https://doi.org/10.1353/hah.2022.0001.

- Kelley, L. 2002b. “Everyday Militarisms in the Kitchen: Baking Strange with Anzac Biscuits.” In Food in Memory and Imagination: Space, Place, and Taste, edited by B. Forrest, and G. de St. Maurice, 239–255. London: Bloomsbury.

- Kelley, L. 2022a. “Biscuit Production and Consumption as War Re-Enactment.” Continuum 36 (5): 763–775. https://doi.org/10.1080/10304312.2022.2106357.

- Kress, G., and T. van Leeuwen. 1996. Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design. London: Routledge.

- Latham, J. 2006. “Technology and” Reel Patriotism” in American Film Advertising of the World War I Era.” Film & History: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Film and Television Studies 36 (1): 36–43. https://doi.org/10.1353/flm.2006.0013.

- Ledin, P., and D. Machin. 2018. “Doing Critical Discourse Studies with Multimodality: From Metafunctions to Materiality.” Critical Discourse Studies 16 (5): 497–513. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2018.1468789.

- Lejeune, P. 1989. Cher cahier: témoignages sur le journal personnel. Paris: Gallimard.

- Lillis, T. 2013. The Sociolinguistics of Writing. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Lubin, D. 2015. Flags and Faces: The Visual Culture of America’s First World War. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Machin, D. 2014. The Language of War Monuments. London: Bloomsbury.

- Machin, D., and A. Mayr. 2012. How to Do Critical Discourse Analysis: A Multimodal Introduction. London: SAGE.

- Madigan, E. 2013. “‘Sticking to a Hateful Task’: Resilience, Humour, and British Understandings of Combatant Courage, 1914–1918.” War in History 20 (1), https://doi.org/10.1177/0968344512455900.

- Martin, N. 2017. “And all Because it is war!’: First World War Diaries, Authenticity and Combatant Identity.” In Writing War, Writing Lives, edited by K. McLoughlin, L. Feigel, and N. Martin. London: Routledge. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.43249781315529615-9/war-first-world-war-diaries-authenticity-combatant-identity-nancy-martin.

- McCaffrey, J. M. 2008. Inside the Spanish-American War. Jefferson: McFarland & Co.

- Murray, A. 2018. Constructing the Memory of War in Visual Culture Since 1914: The Eye on War. London: Routledge.

- O’Hagan, L. A. 2020. “Steal Not This Book My Honest Friends: Threats, Warnings, and Curses in the Edwardian Book.” Textual Cultures 13 (2): 244–274.

- O’Hagan, L. A. 2021. The Sociocultural Forms and Functions of Edwardian Book Inscriptions: Taking a Multimodal Ethnohistorical Approach. New York: Routledge.

- O’Hagan, L. A. 2022. “Introducing Ethnohistorical Research to Multimodal Studies.” Multimodality & Society 2 (4), https://doi.org/10.1177/26349795221132471.

- O’Hagan, L. A. 2023a. “In Memoriam. Documenting Illness, Death and Grief in the Book Inscription (1870-1914).” Textual Cultures 15 (2): 129–158.

- O’Hagan, L. A. 2023b. “In Search of the Social in Social Semiotics: A Historical Perspective.” Social Semiotics, https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2023.2167594.

- Pauwels, L., and D. Mannay. 2020. “Visual Dialogues Across Different Schools of Thought.” In The SAGE Handbook of Visual Research Methods, edited by L. Pauwels, and D. Mannay, 1–13. London: SAGE.

- Pichel, B. 2021. Picturing the Western Front: Photography, Practices and Experiences in First World War. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Prior, P., J. Hengst, K. Roozen, and J. Shipka. 2006. “‘I’ll Be the Sun’: From Reported Speech to Semiotic Remediation.” Text & Talk - An Interdisciplinary Journal of Language, Discourse Communication Studies 26 (6), https://doi.org/10.1515/TEXT.2006.030.

- Reynaud, D. 2020. “‘All Was Not Well With the Soldiers’ Diet’: An Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Official Australian Imperial Force Food Provisions, 1914–18.” First World War Studies 11 (3): 241–256.

- Richardson, M. 2015. The Hunger War: Food, Rations & Rationing 1914-1918. Barnsley: Pen and Sword Military.

- Rose, C. 1994. Property and Persuasion: Essays on the History, Theory, and Rhetoric of Ownership. Boulder: Westview Press.

- Santlofer, J. 2007. ““Hard as the Hubs of Hell”: Crackers in War.” Food, Culture and Society 10 (2): 191–209.

- Saunders, N. J. 2000. “Bodies of Metal, Shells of Memory: ‘Trench Art’, and the Great War Re-cycled.” Journal of Material Culture 5 (1), https://doi.org/10.1177/135918350000500103.

- Saunders, N. J. 2011. Trench Art: A Brief History & Guide, 1914–1939. Barnsley: Pen and Sword Military.

- Saunders, N. J. 2020. Trench Art: Materialities and Memories of War. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Slade, L. 2015. “Trench Art: Sappers and Shrapnel.” Artlink 35 (1): 21–25.

- Smith, M. M. 2015. The Smell of Battle, the Taste of Siege: A Sensory History of the Civil War. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Spijkerman, R., O. Luminet, and A. Vrints. 2018. “Fighting and Writing. The Psychological Functions of Diary Writing in the First World War.” In Experience and Memory of the First World War in Belgium: Comparative and Interdisciplinary Insights, edited by G. Warland, 23–45. Munster: Waxmann.

- Strong, H. 2022. “Tommy’s Teeth: Trench Mouth, Dentures and Dental Health Among British Army Recruits in WW1.” In Cultures of Oral Health: Discourses, Practices and Theory, edited by C. L. Jones, and B. J. Gibson. London: Routledge.

- Stroud, C., and D. Jegels. 2014. “Semiotic Landscapes and Mobile Narrations of Place: Performing the Local.” International Journal of the Sociology of Language, https://doi.org/10.1515/ijsl-2014-0010.

- Supski, S. 2006. “Anzac Biscuits – A Culinary Memorial.” Journal of Australian Studies 30 (87): 51–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/14443050609388050.

- Tester, F. J. 2006. “Art and Disarmament: Turning Arms into Ploughshares in Mozambique.” Development in Practice 16 (2): 169–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614520600562389.

- Thurlow, C., and A. Jaworski. 2014. “Tourism Discourse: Languages and Banal Globalization.” Applied Linguistics Review 2 (1): 285–312.

- Ulrich, B., and B. Ziemann. 2010. German Soldiers in the Great War. Letters and Eyewitness Accounts. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military.

- Venter, L., and A. Wessels. 2022. “British Soldiers’ Anglo-Boer War Experiences as Recorded in Their Diaries.” South African Journal of Cultural History 36 (2), https://doi.org/10.54272/sach.2022.v36n2a4.

- Whittingham, C. 2008. “Mnemonics for War: Trench Art and the Reconciliation of Public and Private Memory.” Past Imperfect (edmonton, Alta ) 14), https://doi.org/10.21971/P76306.