Abstract

The negative effects of pesticide use in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) are often blamed on the “misuse” of pesticides. The industry and government narrative is that the use of highly hazardous pesticides is safe when instructions are followed, and that harm occurs due to “irrational” and “improper” human behavior, linked to lack of knowledge by farmers. This assumption does not consider the real-life situations of pesticide users in LMICs, including structural, economic, and social barriers that make it impossible to follow “safety practices.” This “blame the farmer” narrative leads to ineffective risk mitigation measures, perpetuating and increasing people’s exposure to pesticide harms and endangering their lives. It is governments that allow the use of highly hazardous pesticides in their jurisdictions, and pesticide companies that produce them—not individual pesticide users in LMICs—who should bear the main responsibility for the prevention of the negative impact of these products. A human rights-based approach to pesticide management and the interpretation of international guidance that avoids the blaming narrative but puts real people, their health, and human rights first is needed to reduce and eliminate toxic exposure and save lives and health.

Introduction

Pesticides are designed to kill living organisms such as unwanted plants, animals, insects, and fungi; unfortunately, along with target organisms, they harm human health and the environment (Storck et al., Citation2017). They are currently the only toxic chemicals intentionally released into the environment on a large scale (Pretty, Citation2005). Synthetic chemical pesticides, introduced in the 1930s, especially the organochlorine and organophosphate (OP) insecticides, are more hazardous than their predecessors. Although many organochlorine pesticides have been banned, OPs are still widely used, constituting a large share of acutely toxic highly hazardous pesticides (HHPs).Footnote1 It is critical that exposure to all pesticides, but particularly HHPs, is minimized and/or prevented.

Many negative effects of pesticide use and harmful exposures are blamed by industry and governments on the “misuse” of pesticides in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs; see Goldberg, Citation1985; Larramendy & Soloneski, Citation2019; Singh, Citation2012). The pesticide industry states that pesticides, including HHPs, are “safe” if used according to instructions on the pesticide label and if other risk mitigation measures are implemented (CropLife International, Citation2006). This narrative asserts that people are exposed to and poisoned by pesticides because they lack knowledge of the health risks associated with pesticides, do not read the label where safety information is contained, do not wear appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE), or do not follow hygiene requirements. All of these acts of omission or commission are constructed as behavioral choices on the part of users (Syngenta, Citationn.d.).

Pesticide risk reduction measures for LMICs—suggested by the industry and encouraged by some governments and international guidelines—place the onus of risk reduction on individual pesticide users, many of whom are small-holder farmersFootnote2 or farm workers, rather than on commercial farmers or professional applicators. These “technocratic regimes of protection”Footnote3 shift the cause of the pesticide problem to the deficiencies of knowledge and local cultures and, importantly, to individual user behavior (Galt, Citation2013). They put the responsibility for the “correct” pesticide use on individual users, who are then blamed for the negative consequences of pesticide use.

This article discusses how the concepts of pesticide misuse and safe use (as it is used in relation to small-holders in LMICs) are exploited by powerful social actors to apportion the blame for pesticide harms to pesticide users, rather than acknowledge that some pesticides are simply too toxic for use. Instead of the blaming narrative, it suggests a human rights-based approach to mitigating the risks associated with pesticide use, based on encouraging participation in decision making, information sharing, and prioritization of the rights and interests of farmers and agricultural communities. This article consists of four parts. The first section provides the background on the harms associated with pesticides and their expanded presence in our lives. The second explores the common usage of the terms “misuse,” “responsible use,” and “safe use” of pesticides, and the challenges of the proposed solutions for minimizing pesticide harms.

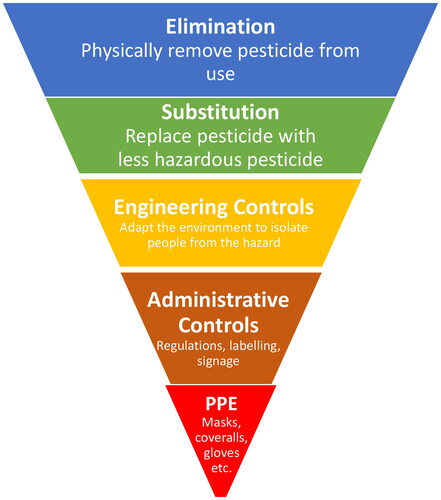

In the third section, to explain why, despite the robust and continuing criticism since the 1970s (Dinham, Citation1991), the safe use concept remains in use, we review international guidelines on pesticide management and the hierarchy of controls (HoC; see ), and their interpretation and implementation. We highlight analogies to other sectors in which evidence-based policies to reduce exposure to commercial determinants of health (CDoH) are undermined by similar claims regarding safe use, personal choice, and personal responsibility.

In the fourth section, we suggest that, to minimize harm to health and the environment, we must reject the “blame the farmer” narrative, together with concepts of safe use and misuse of pesticides. A shift toward a human-rights- and worker-rights-based approach to pesticide management is needed to give priority to voices and interests of farmers and to ensure that governments and businesses fulfill their duties and responsibilities. International guidance that emphasizes protection of health, environment, human rights and livelihoods of agricultural communities over industry’s profits must be given priority.

Pesticide peril

Kirchhelle distinguished four broad historical phases of human–toxic interaction illustrating the expanding presence of chemicals in our society (Kirchhelle, Citation2018). The still unfolding toxic story begins in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries with a period of normalizing toxic presence when chemicals became widely used in industries. During the second period, encompassing the early twentieth century, scientists started to measure and devise thresholds for the presence of toxins in human life to curb toxic exposure with technical fixes. These methods were organized around the goals of work productivity and efficacy of the product, rather than the desire to protect workers or the environment from hazards (Bertomeu Sánchez & Guillem Llobat, Citation2016). During these two periods, it was assumed that chemicals improved productivity and supported the concept of a “clean” and “disease free” home without detriment to humans and the environment.

In the third period, after World War II, with the first glimpses of the environmental impact of chemical toxicity, trust in technical fixes from toxic hazards diminished. Public awareness of the interconnectedness of humans with their environment resulted in concerns about poisoning and food safety, leading to the expansion in pesticide regulation and development of risk control measures. Amid scientific warnings about toxic exposure and media pressure (Mart, Citation2015), Rachel Carson’s 1962 book, Silent Spring, alerted scientists and the public in the United States and globally to the health harms of pesticide use (Carson, Citation2000). It influenced the ban of several persistent organic pollutants and organochlorine insecticides in industrialized countries (Mart, Citation2015). Ironically, this led to the use of less persistent but more toxic OP and carbamate insecticides, placing farmers and farmworkers in an increased danger of acute pesticide poisoning and chronic health outcomes (Galt, Citation2008).

The fourth—current—period is characterized by the ubiquity of pesticides (Shattuck, Citation2021a; Werner et al., Citation2022) in our lives. The realization that the hazard and risk minimization measures do not fully eliminate the negative health and environmental outcomes of chemical exposure led to calls for the reduction in pesticide use and for phasing out of HHPs. Although many high-income countries (HICs) have banned domestic use of HHPs, they continue to manufacture and export them to LMICs for use in agriculture and vector control, impacting the health and lives of farmers, farmworkers, and the public (Dowler, Citation2022; Food and Agriculture Organization & World Health Organisation, Citation2019; Gaberell & Viret, Citation2020).

The problem of pesticide use in agriculture-based LMICs became an international public issue of concern in the early 1980s, partly related to the 1981 publication of the book Circle of Poison by David Weir and Mark Schapiro (Pesticide Action Network Germany, Citation2016). The book highlighted how pesticides banned for use in the United States were exported to LMICs and reappeared as residues in products imported back to the United States. Not only were US citizens exposed to these HHPs, but farm workers in LMICs were starting to see health impacts. In the 1990s, the International Labor Organization (ILO), an international agency established to protect workers and their rights, warned of the “pesticide peril”: exposure to pesticides and agrochemicals that “represent[s] one of the major risks faced by farm workers” (International Labour Organization, Citation1997). In 1990, the ILO adopted the Chemicals Convention No. 170, which aimed to “prevent or reduce the incidence of chemically induced illness and injuries at work” and to protect the public and the environment (International Labour Organization, Citation1990).

Decades later, the global demand for and production and use of pesticides are still increasing, including in LMICs, where capacity to regulate pesticides and control exposures is the weakest (FAOSTAT, Citation2023). Pesticides are pervasive in the environment, including soils, surfaces, and groundwater; their adverse impacts have been observed on bees and natural enemies of pests, bird populations, aquatic organisms, and biodiversity (Food and Agriculture Organization & World Health Organisation, Citation2019; Sarkar et al., Citation2021; United Nations Environment Programme, Citation2022; World Health Organisation, Citation2019). People living and working in LMICs bear the brunt of the negative impact of pesticide exposure and poisoning, affecting their health, lives, and human rights (Chapman & Carbonetti, Citation2011; United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Implications for Human Rights of the Environmentally Sound Management and Disposal of Hazardous Substances and Wastes, 2019). Pesticides affect the estimated 1.3 billion people engaged in agriculture worldwide, constituting half of the global workforce (International Labour Organization, Citation2022).

In low-income countries, more than two-thirds of all workers are engaged in the agricultural sector, as opposed to less than one-third in middle-income countries, and even fewer in HICs (International Labour Organization, Citation2016). The most vulnerable are the 300 to 500 million minority, migrant, casual and temporary workers, small-scale farmers, and unpaid family members, many of whom live in conditions of poverty (International Labour Organization, Citation2022). Pesticide exposure and poisoning cause multiple health problems, from acute injuries to chronic health effects, and are compounded by these conditions (World Health Organization, Citation2018; World Health Organization & Food and Agriculture Organization, Citation2019). Another impact of extensive pesticide use is self-harm with these products: An estimated 385 million cases of unintentional pesticide poisonings, with 11,000 fatalities (Boedeker et al., Citation2020) and 110,000 to 168,000 fatal poisonings due to self-harm with pesticides (Mew et al., Citation2017), occur annually globally.

The prevailing narrative of ‘misuse’ and ‘safe use’

‘Misuse’ of pesticides

The term pesticide “misuse” commonly refers to use, application, and storage practices that are inconsistent with the label instructions (Rother, Citation2018). It is rarely defined, but is often accompanied by such terms as “abuse,” “indiscriminate” (Pingali, Citation1995), “unsafe” (Orozco et al., Citation2009), “improper” or “incorrect” (Larson et al., Citation2021) and “irresponsible,” “ignorant” (London, Citation2003), or simply “off label” useFootnote4 (Verdoorn, Citation2013). The descriptions of such actions are broad and include use for the wrong target pest, at the wrong time, in the wrong dosage, as well as the sale or use of unregistered, adulterated, or misbranded products; combining or mixing pesticides with other chemicals; and inadequate home storage (Larson et al., Citation2021). Failure to implement risk mitigation measures—such as violating specific safety instructions, not wearing PPE, and not using other safety equipment—is also included in this category.

Overuse and overapplication are frequently presented as examples of misuse (Goldberg, Citation1985; Larramendy & Soloneski, Citation2019; Singh, Citation2012). This happens, for example, when farmers spray on a routine basis (advised by extension officers, pesticide vendors, or company representatives) rather than when a pest problem occurs, and when they apply more than the necessary amount of pesticides advised on the label (Pretty, Citation2005). “Misuse” appears to encompass everything not aligned with the good agricultural practices, defined as “the officially recommended or nationally authorized uses of pesticides under actual conditions necessary for effective and reliable pest control” (Food and Agriculture Organization & World Health Organization, Citation2014, p. 14). The US Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA) defined pesticide misuse as “the use of a pesticide in a way that violates laws regulating their use or endangers humans or the environment” (FIFRA Citation1947). Importantly, any consequence of pesticide use may be labeled as misuse and blamed on indiscriminate, improper, irrational, and incorrect use of pesticides (see and ).

Table 1. Examples of the use of the ‘misuse’ concept.

Table 2. Examples of the ‘safe use’ concept.

In the HICs, where most agricultural actors are large family farms and corporations engaged in mechanized agriculture, employing licensed and trained applicators, and where governments have resources to ensure compliance with safety procedures, the responsibility for pesticide use lies with the employer. ILO’s Occupational Safety and Health (OSH) rules specify that it is employers’ duty to protect their employees’ health, safety, and welfare (Alli, Citation2008). In the European Union, the Registration, Evaluation, Authorization and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) legislation—additional OSH standards in chemical management that came into force in 2007—places the responsibility to ensure that manufacturing, importing, distribution, and use of substances does not cause adverse effects onto manufacturers, importers, distributors, and downstream usersFootnote5—companies and professionals, not individual users (Hammerschmidt & Marx, Citation2014). Manufacturers, importers, and downstream users have the responsibility to ensure that they manufacture, place on the market, or use substances that do not adversely affect human health or the environment.

By contrast, in the LMICs—where most pesticide users are small-holder farmers and farm workers on commercial farms and OSH standards are rarely, if ever, effectively enforced, especially in agriculture (International Labour Office, Citation2011; Molina-Guzmán & Ríos-Osorio, Citation2020)—the term “misuse” shifts the blame from pesticide manufacturers, importers, distributors, and commercial farm employers to individual pesticide users. Farmers, agricultural workers, and the population, in general, are held responsible for the unintended effects of pesticide use.

Intentional pesticide ingestion for self-harm at moments of mental crisis—a widespread problem in many agricultural LMICs—has also been considered misuse (Chemical Review Committee & Rotterdam Convention on the Prior Informed Consent Procedure for Certain Hazardous Chemicals and Pesticides in International Trade, Citation2009; Konradsen et al., Citation2005). Pesticides are used in acts of self-harm and suicide not only by agricultural workers but by others in the community, including adolescents (Rother, Citation2010). Intentional poisoning has historically been treated differently from unintentional and occupational poisonings, and is excluded from discussions on the prevention of pesticide poisoning, as it is seen to be the responsibility of the individual involved, beyond the scope of any producer’s responsibility (Syngenta, Citation1987). Even in countries in which a large proportion of suicides are due to pesticide self-poisoning, a clear likelihood of self-harm has not been considered during risk assessment for pesticide registration or reevaluation.

Even though this behavior is clearly linked to easy access to HHPs, this type of harm to health and life has been considered irrelevant for registration processes, as vulnerable people are seen as not deserving protection. Evidence shows that many impulsive self-harm incidents with pesticides are due to their wide availability in rural communities, and that many can be prevented by removing acutely toxic HHPs from circulation (Gunnell et al., Citation2017). Pesticide bans in Sri Lanka between 1995 and 2015 contributed to one of the greatest decreases in suicide rate ever seen, with over a 70% reduction, saving estimated 93,000 lives (Knipe et al., Citation2017). In 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) recommended that the problem of self-poisoning is explicitly considered during pesticide regulation processes (World Health Organisation & Food and Agriculture Organisation, Citation2019).

Despite such recognition by WHO and FAO, intentional misuse is still excluded from the Rotterdam Convention on the Prior Informed Consent Procedure for Certain Hazardous Chemicals and Pesticides in International Trade. Annex II of the Convention clearly states that intentional misuse is not an adequate reason to include a chemical in Annex III of chemicals subject to the prior informed consent (). presents examples of the misuse language used by national authorities and international actors in pesticide management.

‘Safe use’ of pesticides

Inherently connected to the concept of misuse is that of “safe use” of pesticides. The idea that pesticide use is safe when it happens according to label instructions, “correctly” (Sherwood, Citation2009), “properly” (Food and Agriculture Organization, Citation2016), “responsibly” (CropLife International, Citation2017), and “rationally,” and that harm can therefore be avoided, was developed by the pesticide industry, and initially supported by the FAO (Murray & Taylor, Citation2000; Shattuck, Citation2021b). Examples of the safe use concept include statements that pesticides can be used safely if proper precautions are taken (International Labour Organization, Citation1991); if they are applied to crops correctly, according to good agricultural practices (World Health Organization & United Nations Environment Programme, Citation1990); or if they are used according to instructions and labels (World Health Organization, Citation2016b). As early as 1959, the FAO, together with the International Group of National Associations of Manufacturers of Agrochemical Products (GIFAP, now CropLife International) and other industry representatives, started prioritizing safe use programs over other risk mitigation measures, such as reduction in use (Murray, Citation1994; Sherwood & Paredes, Citation2014), and the “safe use pilot project” was globally launched in 1991 with funding from GIFAP (Murray & Taylor, Citation2000).

With the help of GIFAP, the safe use model was entrenched as “the cornerstone for international regimes of protection” in the first version of the International Code of Conduct on the Distribution and Use of Pesticides (1985) (Shattuck, Citation2021c). This voluntary guideline on pesticide management defined the criteria for safe handling, storage, and use of pesticides, embedding the concept of safe use. The code emphasized that safe use could be ensured by proper handling (1.5.3), and by providing information and instructions for use (3.4.3), thus legitimizing the idea that training can ensure the safe use of pesticides (Murray & Taylor, Citation2000).

With the continuing criticism of the safe use concept (elaborated below), the United Nations, including the FAO, has minimized its use of the term. It was dropped from the 2002 revision of the International Code of Conduct on the Distribution and Use of Pesticides and is absent from the fourth (current) version of the Code, now called the FAO/WHO International Code of Conduct on Pesticide Management (Food and Agriculture Organization & World Health Organisation, Citation2014). In 2006, the FAO Council recognized that certain pesticides could not be used without harm in LMICs (Pesticide Action Network Germany, Citation2016) and began to support a progressive ban on HHPs (Food and Agriculture Oganization, Citation2006).

Meanwhile, leading pesticide companies and associations continue to argue that their safe use programs (now referred to as “safe and effective use”) fulfill their responsibility to steward their products. Industry stewardship is defined as “responsible and ethical management of crop protection products from discovery through to ultimate use and beyond” (Croplife International, Citationn.d.), and focuses on administrative and engineering controls, particularly PPE (CropLife International, Citation2006). For example, Syngenta promotes “golden rules for safe use,” which include: (1) caution at all times, (2) understanding the product label, (3) washing after spraying, (4) maintaining application equipment, and (5) using personal protective clothing and equipment (Syngenta Crop Protection AG, Citation2022). illustrates the evolution of the usage of the “safe use” term by national and international actors.

How effective are the suggested pesticide risk mitigation measures?

Analyzing the concept of safe use of pesticides in the context of the HoC will help us understand the effectiveness of the current system of pesticide management in relation to small-holder farmers in LMICs. The HoC, was introduced by the US National Safety Council in 1950, with the aim to control exposures to hazards to protect workers (International Labour Organization, Citation2001; National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health [NIOSH], Citation2015). Control measures are placed in order of decreasing effectiveness and increased supervision required for implementation—elimination of the hazard, substitution of the hazard, engineering controls, administrative controls, and PPE (). Pesticide industry safe use programs incorporate the last three (least effective) elements of the hierarchy, prioritizing PPE as the main risk reduction control measure. Below we discuss in detail the feasibility and effectiveness of the different risk mitigation measures of the HoC in LMICs.

Elimination of hazards is the most effective measure in the HoC. In relation to controlling pesticide hazards, it means the banning and withdrawal of hazardous pesticides from the market. Banning of HHPs responsible for fatal poisonings in Sri Lanka led to over 70% reduction in suicide rate, saving an estimated 93,000 lives between 1995 and 2015 (Knipe et al., Citation2017). Scouting and monitoring to quantify pest pressure to eliminate pesticide usage when pest populations are not above a manageable threshold is also an elimination technique.

Substitution with less hazardous pesticide is promoted by the HoC when pesticide use is unavoidable. Substitution has its risks, as lower toxicity pesticides can still affect beneficial insects or have negative health and environmental effects (Weinberg et al., Citation2009). Furthermore, examples of regrettable substitutions are known, such as when a chemical is replaced with another with unknown or unforeseen hazard (Maertens et al., Citation2021).

Engineering controls involve introducing physical changes to the chemical (e.g., changing a formulation from vapor to solid), equipment, or the environment, including use of special application equipment and arrangements for storage, handling, and disposal of pesticides. These measures would include closed spray systems, leak-proof container packaging of pesticides, reducing the size of pesticide containers, or self-dissolving packaging. They are criticized for having limited effectiveness in LMICs because of cost and difficulty of usage and maintenance (Lamosa et al., Citation2013).

Administrative controls are designed to mitigate hazards through policies and regulations related to restrictions on pesticide use (i.e., the sale of pesticides to licensed applicators, limiting the time and dosage of applications, terms for entry, crop restrictions). Pesticide label requirements is one way of displaying administrative controls; in most countries, a pesticide label is a legally binding document and perceived “misuse” can incur legal penalties. However, the ineffectiveness of labels is common in LMICs: labels are often difficult to read and understand, with many small-scale farmers and farm workers illiterate or unable to follow instructions on the label, particularly when it is written in a foreign language (Rother, Citation2018; Terwindt et al., Citation2018). A 2018 study revealed that labels on pesticide containers in Punjab were frequently written in Hindi and English, but not Punjabi, with letters too small for older people to read (World Health Organization, Citation2016a). Furthermore, in many LMICs, pesticides may be sold after decanting and/or being diluted into informal packaging (e.g., beverage bottles), with the end-user not being able to see the original packaging with the label. Furthermore, the effectiveness of administrative control measures is limited by the difficulties in enforcing restrictions in countries with low regulatory capacity (Dawson et al., Citation2010; Krause et al., Citation2013; Patel et al., Citation2012; Weerasinghe et al., Citation2020; World Health Organization, Citation2009).

Personal protective equipment (i.e., skin, eye, and respiratory protective equipment) is recommended to physically protect applicators from exposure. However, PPE is often absent in work situations, even in HICs, as users note thermal and mechanical discomfort and its high cost (Damalas & Abdollahzadeh, Citation2016; Garrigou et al., Citation2020). In LMICs, PPE is further limited due to a lack of access to the correct equipment specified on the label, and the need to regularly maintain and replace the equipment (Damalas & Abdollahzadeh, Citation2016; Rengam et al., Citation2018; Sharifzadeh et al., Citation2017). Further, PPE only protects the workers who apply pesticides and not other people living in the community (Sherwood & Paredes, Citation2014). When respirators are provided, they are not fully effective in removing the hazard and must be fit tested for each person to be effective (Garrigou et al., Citation2020; Johnson, Citation2016). In practice, most farm workers in LMICs are provided with cheap dust masks to be seen as complying with the rules, yet these may increase exposure if made of absorbent material. Cognizant of these limitations, ILO notes that PPE should be considered as the last line of defense after all other measures of the HoC have been taken (International Labor Organization).

The current, fourth version of the FAO/WHO International Code of Conduct on Pesticide Management includes many administrative and engineering control measures (e.g., restrictions on the availability of WHO hazard Class I and Class II HHPs to licensed operators, provisions on PPE), but also recognizes their limitations. It notes that “pesticides whose handling and application require the use of personal protective equipment that is uncomfortable, expensive, or not readily available should be avoided, especially in the case of small-scale users and farm workers in hot climates” (Article 3.6). Article 7.5 notes, “prohibition of the importation, distribution, sale, and purchase of highly hazardous pesticides may be considered if, based on risk assessment, risk mitigation measures or good marketing practices are insufficient to ensure that the product can be handled without unacceptable risk to humans and the environment” (Food and Agriculture Organization & World Health Organization, Citation2014).

Other provisions of the code emphasize minimizing potential health and environmental risks of pesticides (Articles 1.5 and 1.7.3), production and use of less toxic formulations (Article 5.2.4), and special precautions for vulnerable groups (Article 11.1). Echoing the importance of these measures, the FAO/WHO JMPM Guidelines on Highly Hazardous Pesticides, developed to provide guidance to regulators, particularly in LMICs, note that the main risk mitigation measures—eliminating and substituting HHPs with less hazardous pesticides—are at the top of the efficacy scale of the HoC for reducing HHP risks (Food and Agriculture Organization, Citation2016).

Even in HICs, with a higher financial and human resource capacity to implement the HoC, the first three elements lack effectiveness in reducing pesticide risks (Coffman et al., Citation2009; Garrigou et al., Citation2020; Levesque et al., Citation2012). In LMICs, these measures are dramatically insufficient. None of these control methods is relevant to self-poisoning with pesticides. By concentrating on the least effective elements of the HoC, the safe use narrative diverts attention and resources from the evidence-based interventions with proven effectiveness, thus increasing harms. The focus of implementation of the code should be on elimination and substitution of HHPs, with less hazardous alternatives. A phase-out of HHPs in LMICs’ agriculture is consistent with the principles laid out in the code and has been proven to be effective in reducing pesticide deaths and poisonings (Gunnell et al., Citation2017; Lee et al., Citation2021).

Real life situations of small-holder farmers and farm workers

The assumption that pesticide harms happen due to irrational, improper behavior and lack of knowledge (e.g., ignorance) by farmers and farm workers points to good guys—the industry—who worry about farmers and food security, and bad guys—the users who fail to use industry’s products “safely” and are not able to follow instructions (Jansen, Citation2017).

The real-life situations in which pesticides are used are not that simple. What is defined as safe and assumed to be safe and reasonable during pesticide risk assessments may be unreasonable in the climates and real-life situations of most LMICs. For example, registering HHPs under the proviso of PPE use is unrealistic in climates experiencing high temperatures and where the required PPE is not readily available.

Safe use training that the industry relies on as the main method of delivering knowledge rests on an overly simplistic model of behavior, focusing on a single constraint—lack of information (Galt, Citation2008). This emphasis on knowledge ignores numerous other constraints—political, economic, cultural, individual, and environmental (Galt, Citation2013). As Pretty pointed out, “Contrary to the assumption that farmers handle pesticides in a risky manner because of the lack of knowledge about dangers of pesticides, most farmers do generally know that pesticides are toxic” (Pretty, Citation2005). Studies show that lack of knowledge is not a strong predictor of poisoning risk (Lekei et al., Citation2014), and that knowledge alone does not produce changes in behavior, as safe practices are not adopted or maintained when they are costly or inconvenient (Afshari et al., Citation2021; Naidoo et al., Citation2010). “Health effects of pesticides are at least ‘partially known’ by farmers, but do not register as urgent, actionable, or particularly important given the range of other risks people face in their everyday lives, and the range of choices about how to avoid it” (Shattuck, Citation2021b).

Similarly, London noted that pesticide exposure and poisoning take place in a wider social context, beyond the simplicity of the ignorance-poisoning nexus, because of factors over which victims of pesticide poisoning have no, or limited, control. He noted that, instead of blaming workers for “ignorance,” “carelessness,” and “negligence,” these notions would be more appropriately applied to the employers, public officers, and health professionals who failed to act to prevent poisoning (London, Citation2003). Rother extended this, noting that, in order to follow the rules (e.g., label instructions), farmers and other agricultural workers need not only to know about the dangers of pesticides but also to be provided with the means to be able to comprehend them (Rother, Citation2018). Importantly, nonusers who are not working directly with pesticides—but who are at risk of pesticide exposures from drift, washing contaminated clothing, harvesting in sprayed fields, and eating foods with residues—are not protected by pesticide company instructions; protective equipment and training does not prevent these exposures (Asmare et al., Citation2022; Sherwood & Paredes, Citation2014).

These real-life situations point to inequality and social, political, cultural, and other constrains faced by agricultural communities and small-holder farmers in LMICs in pesticide risk reduction. An alternative to the current technocratic regime is needed to take account of the real-life situations of pesticide use in LMIC, vulnerabilities of farmers and agricultural communities, and the power imbalance between the actors. What is needed is a human rights-based approach to pesticide management as a normative basis for claiming the central role for agricultural communities and farmers in LMICs in pesticide risk reduction and decision making.

The need for a human rights-based approach to pesticide management

Many socio-economic factors make it difficult for people working and living in LMICs to protect themselves from the negative effects of pesticides. Poverty; lack of employment opportunities and social, health, and community services; gender inequality; domestic violence; dowry issues; power inequalities in the workplace; and long distances to urban areas where higher quality services are available—all of these factors put farmers, farm workers, and rural communities in situations of vulnerability (Chapman & Carbonetti, Citation2011; United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Implications for Human Rights of the Environmentally Sound Management and Disposal of Hazardous Substances and Wastes, 2019). Inability to meaningfully participate in decision making, corruption and corporate capture of government agencies, violence, lack of remedy to protect themselves, threat of reprisals, and difficulties gathering evidence of harm exacerbate this vulnerability further. The UN Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas affirms that people living and working in rural areas—being especially affected by climate change, poverty, and the changing dynamics in agriculture, input and food markets, food security, and modes of livelihood—are among the world’s most vulnerable groups (United Nations Human Rights Council, Citation2018), underlining that special measures need to be taken to lessen the impact of pesticides on their rights and lives.

The misuse narrative further exacerbates the already unequal power relations between small-holder farmers and agricultural corporations, and between farm workers and employers, absolving corporations of responsibility and contributing to people’s vulnerability to the negative effects of pesticide use (Dinham, Citation1991; Murray, Citation1994; Murray & Taylor, Citation2000).

The need to counter inequality inherent in pesticide management makes a strong case for the application of a human rights approach to pesticide management. Human rights provide a universal framework for advancing justice and equality, transforming moral imperatives into legal entitlements (Gostin et al., Citation2018). This approach would provide an analysis of the various vulnerabilities of actors and inequalities at the heart of the pesticide management regime to redress of the discriminatory practices and the unjust distributions of power (Orozco et al., Citation2009). This approach would also start the process of holding governments accountable for their actions, implemented through a human rights critique of their policies, by challenging their actions through litigation, demanding redress in cases of violation, and proactively developing policies consistent with human rights. It would support the mobilization of farmers’ and other grassroots groups, strengthening the agency and participatory and decision-making involvement of the rights-holders to amplify the voices of the affected communities.

A human rights-based approach is especially important in holding governments accountable for their legal obligations to protect the rights of vulnerable groups. It reshapes the power dynamic and strengthens claims of discriminated-against, powerless, and disenfranchised peoples. It can provide an equality-based solution to a wide range of public health threats, transforming recipients of government benevolence and victims of corporate greed into right-holders.

Human rights, the pesticide industry, and the CDoH

Reliance on shifting the narrative for exposure to health harming products onto individual users of the product has been identified as a common strategy industry uses to avoid evidence-based policies across a range of risk exposures for noncommunicable diseases. Strategies emphasizing personal responsibility (or “freedom of choice” to use harmful products) have been adopted by the tobacco (Carter, Citation2003; Friedman et al., Citation2015), gambling (van Schalkwyk et al., Citation2022), alcohol (Maani Hessari & Petticrew, Citation2017; McCambridge et al., Citation2018; Mialon & McCambridge, Citation2018), and unhealthy food industries (Yates et al., Citation2021; Zaltz et al., Citation2022). So far, the analysis of the CDoH—defined as strategies and approaches used by the private sector to promote products and choices that are detrimental to health—including decontextualizing risk and converting it into a matter of personal behavior choice, has not been used in relation to pesticide industry. It is, however, important that the CDoH lens is applied to the pesticide industry, allowing scholars and advocates to analyze and learn how to respond to the playbook used by industries seeking to protect their markets for potentially health-harming products (Jacquet, Citation2022; Lacy-Nichols et al., Citation2022).

The human rights-based approach to pesticide management offers at least a partial response to the questions presented by the CDoH and the influence of the pesticide industry in dictating consumer choices. Empowering pesticide users—particularly small-holder farmers in LMICs—with legal and human rights tools will help to account for their power imbalance in relation to the pesticide industry. Where CDoH may undermine actions aimed at protecting health and lives through political and economic clout and nontransparent business practices, the human rights-based approach can help to limit corporate power in favor of the individual user/farmer, facilitating access to information, resources, and ability to resist the “blame the farmer” narrative, and insisting on human rights due diligence to identify and prevent negative human rights impacts of corporate activities (United Nations Human Rights Council, Citation2023).

Applying the human rights-based approach to pesticide management

Under international human rights law, states have a legal obligation to respect, protect, and fulfill the human rights of people residing in their territories. The obligation to respect human rights requires states to refrain from engaging in conduct that interferes with the enjoyment of human rights. States should avoid registering HHPs, eliminate tax incentives and subsidies for their use, and refrain from marketing and advertising their use.

The obligation to protect human rights requires states to protect individuals and groups from human rights abuses and ensure that third parties respect these rights. States must ensure that pesticide and agricultural industries and employers comply with environmental, human rights, and other standards, provide adequate information while marketing their products, and limit marketing that is harmful.

The obligation to fulfill requires states to take positive action to facilitate the enjoyment of human rights, including by creating legal, institutional, and procedural conditions to fully realize human rights implicated by pesticides. This may include the duty to enact and enforce necessary laws and policies on sound management of chemicals and pesticides and adopt legislation addressing the heightened vulnerability of farmers and agricultural workers. Within this obligation, states should provide extension services free of corporate influence and access to biomonitoring and risk assessment services, actively build capacity of farmers, and fund research into pesticide replacement and non-pesticide pest control. Overall failure to take measures to limit the harmful effects of exposure to pesticides is a breach of a state’s obligation to respect, protect, and fulfill it human rights obligations (Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, UNEP, Citationn.d.).

Pesticide manufacturers have a responsibility to respect human rights and must refrain from any action that may have harmful effect on them. To do so, they are required to exercise human rights due diligence to identify, prevent, mitigate, and account for the impacts of their activities on human rights (United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, Citation2011). These responsibilities are delineated in the voluntary Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, endorsed by the UN Human Rights Council in 2011. Currently, the global community is working to elaborate an international legally binding instrument to regulate, in international human rights law, the activities of transnational corporations and other business enterprises (United Nations Human Rights Council, Citation2023).

Employers and pesticide manufacturers need to bear the responsibility to ensure safety at work and that HHPs do not adversely affect health and the environment (United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, Citation2011; United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Implications for Human Rights of the Environmentally Sound Management and Disposal of Hazardous Substances and Wastes, 2019). Pesticide manufacturers and employers—not users—bear the primary responsibility for the consequences of exposures of workers to toxic substances at the workplace (United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, Citation2011; United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Implications for Human Rights of the Environmentally Sound Management and Disposal of Hazardous Substances and Wastes, Citation2017). They and governments must ensure that chemicals that cannot be used safely by end-users are not placed on the market. Workers’ rights include a right to adequate knowledge, and a right to stop work in the case of imminent danger to safety or health (Alli, Citation2008). In 2019, the UN Human Rights Council confirmed that workers have the right to be protected from pesticide exposure and poisoning (Human Rights Council, Citation2019).

Protection of life and health at work are of particular importance in the context of pesticide management and are a part of the human rights framework. In 2022, the ILO recognized health and safety at work as a fundamental right, further entrenching work health and safety as parts of the human rights framework. It forms a foundation for the states’ and businesses’ duty to protect the human rights of workers to prevent exposures to toxic substances and the acknowledgment that hazard elimination is paramount in preventing exposure.

Human rights are interdependent and indivisible, which means that one right cannot be fully enjoyed without the others. Exposure to pesticides threatens not only the right to health but also the rights to life, bodily integrity, and healthy environment. The right to life includes an obligation of the state to adopt appropriate measures to protect life from all reasonably foreseeable threats, including from acts and omissions that may be expected to cause unnatural or premature death (United Nations Human Rights Committee, Citation2018). This includes measures to prevent self-poisonings and suicide, particularly for people in the situation of vulnerability (Utyasheva & Eddleston, Citation2021). The right to health includes access to health-related information, including on pesticide hazards and the ways to avoid them (United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, Citation2000). The right to food involves affordable, adequate, and safe food free of toxic chemicals (Elver, Citation2017). The right to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment includes creation of a nontoxic environment for current and future generations (United Nations General Assembly, Citation2022). Together, a comprehensive human rights-based approach to pesticide management integrates the right to health; the right to life; the rights to a healthy environment, health, and safety at work; participation in decision making; the right to information; and the right to benefit from science.

Shifting the dialogue

Applying the human rights-based approach to the Code of Conduct means identifying those whose health and rights are disproportionately affected by pesticides and using its provisions to protect them. Analysis of the code in terms of farmers’ and farm workers’ rights will help address the health and human rights effects of pesticide use and counter the inequalities inherent in the current system of pesticide management.

The human rights-based approach to pesticide management aligns with the mounting pressure to address pesticide dependency, particularly the use of HHPs in LMICs. In 2006, the FAO Council recommended that member states consider a progressive ban of HHPs. The 2015 International Conference on Chemicals Management (ICCM4) supported this call. The 2019 FAO/WHO “Detoxifying Agriculture” report called for a progressive phase out of HHPs by more sustainable alternatives (Food and Agriculture Organization & World Health Organisation, Citation2019). This is further supported by the guidance developed by the UN Special Rapporteur on human rights and toxics, which reaffirms the paramount importance of hazard elimination in preventing exposure to pesticides and supporting human rights protection (Pearson et al., Citation2017; United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Implications for Human Rights of the Environmentally Sound Management and Disposal of Hazardous Substances and Wastes, 2019). Yet, to date, these remain as words on paper rather than action in countries.

The application of the human rights-based approach implies the following:

The concept of misuse of pesticides by individual users in LMICs should be phased out as an explanatory factor at population level, and the distinction between intentional and unintentional misuse of pesticides reconfigured in policy terms as unwarranted. This is because “misuse” may be one of the few possible actions available to users in the prevailing circumstances on the ground.Footnote6 These concepts must be avoided in policy, research, and legislation.

The fact that some pesticides are too toxic to be used by small-holder farmers and farm workers in the LMICs needs to be recognized. The focus of implementation of the Code of Conduct should be on the elimination and substitution of HHPs with less hazardous alternatives rather than reliance on ineffectual safe use trainings, as well as regulating from a hazard-based rather than a risk-based approach.

Pesticide poisonings, including pesticide suicides and self-harm, should be considered an occupational health condition when “work provides easy access to potential dangers,” similar to alcoholism among bar staff (Schilling, Citation1989). Pesticide poisonings happen due to the wide availability and accessibility of highly toxic pesticides in everyday lives, and governments have a duty to take positive actions to protect people’s rights and eliminate these substances from use, particularly in LMICs.

Pesticide manufacturers must be held accountable to take responsibility for the life cycle impact of their products on human health and must ensure that their products do not adversely affect health and the environment.

Mainstreaming human rights into pesticide policies and regulations, including the Code of Conduct, means that rights and voices of the agricultural communities, farmers, and farm workers need to become the primary consideration of pesticide management, providing guidance to pesticide use reduction and poisoning prevention efforts. Farmers’ and farm workers’ rights to access and understand information about the impact of pesticide exposure and poisoning, to have access to or know about the alternatives, and to participate in decision making are important elements of the human rights-based approach.

Conclusion

Concepts of pesticide misuse and safe use must be removed from global and national pesticide management policies and regulatory narratives, together with the view that HHPs can ever be used safely. In a human rights-based approach to pesticide management, the recommendation of the FAO/WHO International Code of Conduct on Pesticide Management to prioritize measures to minimize harm to health needs to be taken seriously. Human rights—such as the rights to life; health; information; science; remedy; a safe, clean, healthy, and sustainable environment; clean water and food; safe working conditions; and participation—need to come together to protect farmers, farm workers, rural communities, and the general population in LMICs against pesticide exposure and poisoning. Protection, fulfillment, and respect for human rights in relation to pesticide management will help the implementation of all Sustainable Development Goals, particularly the ones directly related to health and toxic chemicals, including addressing pesticide poisoning (i.e., Target 3.9).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to extend their gratitude to Baskut Tuncak, director of the Massachusetts Toxics Use Reduction Institute (TURI) and the UN Human Rights Council’s Special Rapporteur on human rights and toxics (2014–2020) for insightful comments on the article.

Disclosure statement

Andrea Rother and Michael Eddleston at the time of writing were members of the FAO/WHO Joint Meeting on Pesticide Management (JMPM).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Leah Utyasheva

Leah Utyasheva is a Policy Director for the Centre for Pesticide Suicide Prevention (CPSP) at the University of Edinburgh. Leah holds a PhD in and has extensive experience as a human rights researcher and policy and law reform analyst. She has worked on gender equality, migration, health, and protection from discrimination for vulnerable communities. Her current interests include human rights-based approach to pesticide management, prevention of pesticide suicide, policy initiatives to improve suicide reporting, and decriminalization of suicide attempt.

Hanna-Andrea Rother

Hanna-Andrea Rother is a Professor and Head of the Environmental Health Division in the School of Public Health at the University of Cape Town, South Africa. Her research and teaching focus on pesticide/chemical risk management, risk communication, children’s environmental health, commercial determinants of health, capacity building for LMIC regulators and the development of risk reduction interventions. She is a WHO panel advisor for the FAO/WHO Joint Meeting on Pesticide Management and an international Board Member for the European Partnership for the Assessment of Chemicals (PARC). She contributes extensively to national, regional and international pesticide/chemicals policies and conventions advocating for risk reduction/prevention for vulnerable populations in LMICs, especially Africa.

Leslie London

Leslie London is a Professor in Public Health in the School of Public Health at the University of Cape Town, South Africa. He is Head of the Division of Public Health Medicine and leads the Health and Human Rights programme in the School and is an active researcher in the Centre for Environmental and Occupational Health Research in areas related to pesticides, farm worker health, neurotoxic chemicals and environmental health policy. He is a Fellow of the Collegium Ramazzini, a member of the International Commission on Occupational Health, active in the Peoples Health Movement and part of the steering committee of the network on Governance and Conflict of Interest in Public Health (GECI-PH).

Michael Eddleston

Michael Eddleston Michael is Professor of Clinical Toxicology in the Pharmacology, Toxicology and Therapeutics Unit of the University of Edinburgh, and Consultant Physician at the National Poisons Information Service, Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh. He trained in medicine at Cambridge and Oxford, with an intercalated PhD at the Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla. Michael’s primary research aim is to reduce deaths from pesticide and plant self-poisoning globally, a cause of as many as 200,000 premature deaths each year and the number two global means of suicide. To do this, he performs clinical trials in South Asian district hospitals to better understand the pharmacology & effectiveness of antidotes and community-based controlled trials to identify effective public health interventions. He has established the Centre for Pesticide Suicide Prevention (www.centrepsp.org) and a NIHR RIGHT Programme: Preventing deaths from acute poisoning in low- and middle-income countries at the University of Edinburgh to drive research into suicide prevention and acute poisoning.

Notes

1 Highly hazardous pesticides are defined as “Pesticides that are acknowledged to present particularly high levels of acute or chronic hazards to health or environment according to internationally accepted classification systems such as WHO or GHS or their listing in relevant binding international agreements or conventions. In addition, pesticides that appear to cause severe or irreversible harm to health or the environment under conditions of use in a country may be treated as highly hazardous.” HHPs are primarily older, off-patent chemicals that are no longer permitted in many high-income countries due to unacceptable risks to human health and the environment but are still used in LMICs because of inadequate regulation and monitoring (Food and Agriculture Organization, Citation2012).

2 Following the definition provided by the FAO, small-holder farmers are small-scale farmers who manage areas varying from less than one hectare to 10 hectares. Small-holder farmers are characterized by family-focused motives, using mainly family labor for production, and using part of the produce for family consumption. Small-holders provide up to 80% of food supply in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, where more than 1.5 billion people live in small-holder households (Food and Agriculture Organization, Citation2012).

3 Galt defined technocratic regimes of protection as efforts to protect lives that are limited to (1) technical rationality that focuses exclusively on issues of instrumental action that attempts to predict and control events, objects, and people; and (2) didactic communication of pesticide hazards to people seen to be at risk because of their individual decision-making. In this framing, he pointed out, “poisonings are considered the consequence of misuse or abuse of pesticides, and ‘safe use’ is the responsibility of the farmer” Galt (pp. 336–337 Citation2013).

4 Verdoorn listed the following consequences of off-latel use: “[s]uicide attempts, incorrect treatment of household and garden pests, unsafe storage of pesticides, illegal sales of decanted pesticides in unmarked containers, homicides, excessive use of pesticides in home and home garden applications, illegal storage in unmarked food and beverage containers, and blatant ignorance” Verdoorn (Citation2013, p. 288).

5 Downstream user means any natural or legal person established within the community, other than the manufacturer or the importer, who uses a substance, either on its own or in a mixture, in the course of his industrial or professional activities. A distributor or a consumer is not a downstream user. (Article 3(13); European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) (Citation2014).

6 A shift, like the one that is happening with the rejection of the terms of alcohol use disorder and substance misuse, is necessary to avoid stigma and judgment and to recognize the complex social factors underlying these phenomena.

References

- Afshari, M., Karimi-Shahanjarini, A., Khoshravesh, S., & Besharati, F. (2021). Effectiveness of interventions to promote pesticide safety and reduce pesticide exposure in agricultural health studies: A systematic review. PLoS One, 16(1), e0245766. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245766

- Alli, B. (2008). Fundamental principles of occupational health and safety. International Labour Organisation.

- Asmare, B., Freyer, B., & Bingen, J. (2022). Women in agriculture: Pathways of pesticide exposure, potential health risks and vulnerability in sub-Saharan Africa. Environmental Sciences Europe, 34(1), 89–103. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-022-00638-8

- Bertomeu Sánchez, J. R., & Guillem Llobat, X. (2016). Following poisons in society and culture (1800-2000): A review of current literature. Actes D’Historia De La Ciencia I de La Tecnica. Nova Epoca, 9, 9–36.

- Boedeker, W., Watts, M., Clausing, P., & Marquez, E. (2020). The global distribution of acute unintentional pesticide poisoning: Estimations based on a systematic review. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1875–1894. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09939-0

- Carson, R. (2000). Silent spring. Penguin.

- Carter, S. M. (2003). From legitimate consumers to public relations pawns: The tobacco industry and young Australians. Tobacco Control, 12(Suppl 3), 71–78. https://doi.org/10.1136/tc.12.suppl_3.iii71

- Chapman, A., & Carbonetti, B. (2011). Human rights protections for vulnerable and disadvantaged groups: The contributions of the UN Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights. Human Rights Quarterly, 33(3), 682–732. https://doi.org/10.1353/hrq.2011.0033

- Chemical Review Committee & Rotterdam Convention on the Prior Informed Consent Procedure for Certain Hazardous Chemicals and Pesticides in International Trade. (2009). Additional legal opinion on intentional misuse anf the application of criterion (d) of Annex II to the Convention (Review of the outcome of the fourth meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Rotterdam Convention relevant to the Committee’s work).

- Coffman, C. W., Stone, J. F., Slocum, A. C., Landers, A. J., Schwab, C. V., Olsen, L. G., & Lee, S. (2009). Use of engineering controls and personal protective equipment by certified pesticide applicators. Journal of Agricultural Safety and Health, 15(4), 311–326. https://doi.org/10.13031/2013.28886

- CropLife International. (2006). Guidelines for the safe and effective use of crop protection products. https://croplife.org/wp-content/uploads/pdf_files/Guidelines-for-the-safe-and-effective-use-of-crop-protection-products.pdf

- CropLife International. (2017). Pesticide retailer course. Trainer Manual. https://croplife.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Pesticide-Retailer-Course_VApril2017.pdf

- Croplife International. (n.d.). Promoting stewardship. CropLife International. https://croplife.org/crop-protection/stewardship/

- Damalas, C. A., & Abdollahzadeh, G. (2016). Farmers’ use of personal protective equipment during handling of plant protection products: Determinants of implementation. Science of the Total Environment, 571, 730–736. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.07.042

- Dawson, A. H., Eddleston, M., Senarathna, L., Mohamed, F., Gawarammana, I., Bowe, S. J., Manuweera, G., & Buckley, N. A. (2010). Acute human lethal toxicity of agricultural pesticides: A prospective cohort study. PLoS Medicine, 7(10), e1000357. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000357

- Dinham, B. (1991). FAO and pesticides: Promotion or proscription? The Ecologist (1979), 21(2), 61–76.

- Dowler, C. (2022). Revealed: UK shipped more than 10,000 tonnes of banned pesticides overseas in 2020. https://unearthed.greenpeace.org/2022/02/22/bees-syngenta-paraquat-uk-exports/

- Elver, H. (2017). Report of the Special Rapporteur on the right to food. A/HRC/34/48.

- European Chemicals Agency (ECHA). (2014). Guidance for downstream users. https://echa.europa.eu/documents/10162/23036412/du_en.pdf/9ac65ab5-e86c-405f-a44a-190ff4c36489

- FAOSTAT. (2023). Pesticide trade. FAO. https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/?#data/RP/visualize

- FIFRA. (1947). Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodeniticide Act of 1947.

- Food and Agriculture Organization. (2006). Report of the Council of FAO.

- Food and Agriculture Organization. (2012). Smallholders and family farmers. Factsheet. (Sustainability Pathways. https://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/nr/sustainability_pathways/docs/Factsheet_SMALLHOLDERS.pdf

- Food and Agriculture Organization. (2016). International code of conduct on pesticide management. Guidelines on highly hazardous pesticides. https://www.fao.org/documents/card/en?details=a5347a39-c961-41bf-86a4-975cdf2fd063

- Food and Agriculture Organization. (2017). FAO’s Position on the use of pesticides to combat fall armyworm. https://www.fao.org/3/i8022e/i8022e.pdf

- Food and Agriculture Organization. (2022). Pesticides use, pesticides trade and pesticides indicators. Global, regional and country trends, 1990-2020 (FAOSTAT Analytica Brief 46, Issue. https://www.fao.org/3/cc0918en/cc0918en.pdf

- Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations. (2022). Pest and pesticide management. FAO. https://www.fao.org/pest-and-pesticide-management/pesticide-risk-reduction/pesticide-management/en/

- Food and Agriculture Organization & World Health Organisation. (2014). The international code of conduct on pesticide management. FAO. http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/agphome/documents/Pests_Pesticides/Code/CODE_2014Sep_ENG.pdf

- Food and Agriculture Organization & World Health Organisation. (2019). Detoxifying agriculture and health from highly hazardous pesticides - A call for action. http://www.fao.org/3/ca6847en/ca6847en.pdf

- Friedman, L. C., Cheyne, A., Givelber, D., Gottlieb, M. A., & Daynard, R. A. (2015). Tobacco industry use of personal responsibility rhetoric in public relations and litigation: Disguising freedom to blame as freedom of choice. American Journal of Public Health, 105(2), 250–260. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2014.302226

- Gaberell, L., Viret, G. (2020). Banned in Europe: How the EU exports pesticides too dangerous for use in Europe. https://www.publiceye.ch/en/topics/pesticides/banned-in-europe

- Galt, R. E. (2008). Beyond the circle of poison: Significant shifts in the global pesticide complex, 1976–2008. Global Environmental Change, 18(4), 786–799. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2008.07.003

- Galt, R. E. (2013). From Homo economicus to complex subjectivities: Reconceptualizing farmers as pesticide users. Antipode, 45(2), 336–356. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.2012.01000.x

- Garrigou, A., Laurent, C., Berthet, A., Colosio, C., Jas, N., Daubas-Letourneux, V., Filho, J.-M J., Jouzel, J.-N., Samuel, O., Baldi, I., Lebailly, P., Galey, L., Goutille, F., & Judon, N. (2020). Critical review of the role of PPE in the prevention of risks related to agricultural pesticide use. Safety Science, 123, 104527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2019.104527

- Goldberg, K. A. (1985). Efforts to prevent misuse of pesticides exported to developing countries: progressing beyond regulation and notification. Ecology Law Quarterly, 12(4), 1025–1051. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24112835

- Gostin, L. O., Meier, B. M., Thomas, R., Magar, V., & Ghebreyesus, T. A. (2018). 70 years of human rights in global health: Drawing on a contentious past to secure a hopeful future. Lancet, 392(10165), 2731–2735. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32997-0

- Gunnell, D., Knipe, D., Chang, S.-S., Pearson, M., Konradsen, F., Lee, W. J., & Eddleston, M. (2017). Prevention of suicide with regulations aimed at restricting access to highly hazardous pesticides: A systematic review of the international evidence. The Lancet Global Health, 5(10), e1026–e1037. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2214-109x(17)30299-1

- Hammerschmidt, T., & Marx, R. (2014). REACH and occupational health and safety. Environmental Sciences Europe, 26(1), 6–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/2190-4715-26-6

- Human Rights Council. (2019). Resolution on protection of the rights of workers exposed to hazardous substances and wastes (42/21e). https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3836800

- Imperial Chemical Industries PLC. (1983). Response to IPCS Environmental Health Criterai Document: Paraquat [Response to report].

- International Labour Office. (2011). Safety and health in agriculture. (ILO Code of practice., Issue. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/–-ed_dialogue/–-sector/documents/normativeinstrument/wcms_161135.pdf

- International Labour Organization. (1979). Guide to health and hygiene in agricultural work http://www.nzdl.org/cgi-bin/library.cgi?e=d-00000-00–-off-0cdl–00-0––0-10-0–-0–-0direct-10–-4–––-0-1l–11-en-50–-20-preferences–-00-0-1-00-0-0-11-1-0utfZz-8-10&a=d&c=cdl&cl=CL1.194&d=HASH2af972bd68a2a8ac71b4ad.6.1

- International Laboiur Organization. (1985). Safe use of pesticides (Occupational Safety and Health Seeries, Issue. http://www.nzdl.org/cgi-bin/library?e=d-00000-00–-off-0cdl–00-0––0-10-0–-0–-0direct-10–-4–––-0-1l–11-en-50–-20-about–-00-0-1-00-0–4––0-0-11-10-0utfZz-8-10&cl=CL2.19&d=HASH01aad7a1ebf21356c0688032.2&x=1

- International Labour Organization. (1990). Convention concerning safety in the use of chemicals at work (C170). https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_INSTRUMENT_ID:312315

- International Labour Organization. (1991). Safety and health in the use of agrochemicals. A Guide.

- International Labour Organization. (1997). ILO warns on farm safety. Agriculture mortality rates remain high. Pesticide pose major health risks to global workforce. https://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_008027/lang–en/index.htm

- International Labour Organization. (2001). Safety and health in agriculture. Recommendation. No 192. https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:R192

- International Labour Organization. (2016). Key indicators of the labour market. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/–-dgreports/–-stat/documents/publication/wcms_498929.pdf

- International Labour Organization. (2022). Agriculture: a hazardous work. ILO. https://www.ilo.org/safework/areasofwork/hazardous-work/WCMS_110188/lang–en/index.htm

- Jacquet, J. (2022). The playbook: How to deny science, sell lies, and make a killing in the corporate world. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. https://books.google.ca/books?id=595CEAAAQBAJ

- Jansen, K. (2017). Business conflict and risk regulation: Understanding the influence of the pesticide industry. Global Environmental Politics, 17(4), 48–66. https://doi.org/10.1162/GLEP_a_00427

- Johnson, A. (2016). Respirator masks protect health but impact performance: a review. Journal of Biological Engineering, 10(1), 4–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13036-016-0025-4

- Kirchhelle, C. (2018). Toxic tales—recent histories of pollution, poisoning, and pesticides (ca. 1800–2010). NTM, 26(2), 213–229. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00048-018-0190-2

- Knipe, D., Chang, S.-S., Dawson, A., Eddleston, M., Konradsen, F., Metcalfe, C., & Gunnell, D. (2017). Suicide prevention through means restriction: Impact of the 2008-2011 pesticide restrictions on suicide in Sri Lanka. PLoS One, 12(3), e0172893. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0172893

- Konradsen, F., van der Hoek, W., Gunnell, D., & Eddleston, M. (2005). Missing deaths from pesticide self-poisoning at the IFCS Forum IV. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 83(2), 157–158. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/260560

- Krause, K.-H., van Thriel, C., De Sousa, P., Leist, M., & Hengstler, J. (2013). Monocrotophos in Gandaman village: India school lunch deaths and need for improved toxicity testing. Archives of Toxicology, 87(10), 1877–1881. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00204-013-1113-6

- Lacy-Nichols, J., Marten, R., Crosbie, E., & Moodie, R. (2022). The public health playbook: Ideas for challenging the corporate playbook. The Lancet Global Health, 10(7), e1067–e1072. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(22)00185-1

- Lamosa, S., Marey-Perez, M., Cabaleiro, C., & Barrasa, M. (2013). Analysis of pesticide application and applicator’s training level in greenhouse farms in Galicia, Spain. Agricultural Economics Review, 14(2), 5–13.

- Larramendy, M., & Soloneski, S. (2019). Pesticides - use and misuse and their impact in the environment. IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.78909

- Larson, A. J., Paz-Soldán, V. A., Arevalo-Nieto, C., Brown, J., Condori-Pino, C., Levy, M. Z., & Castillo-Neyra, R. (2021). Misuse, perceived risk, and safety issues of household insecticides: Qualitative findings from focus groups in Arequipa, Peru. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 15(5), e0009251. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0009251

- Lee, Y. Y., Chisholm, D., Eddleston, M., Gunnell, D., Fleischmann, A., Konradsen, F., Bertram, M. Y., Mihalopoulos, C., Brown, R., Santomauro, D. F., Schess, J., & van Ommeren, M. (2021). The cost-effectiveness of banning highly hazardous pesticides to prevent suicides due to pesticide self-ingestion across 14 countries: An economic modelling study. The Lancet Global Health, 9(3), e291–e300. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30493-9

- Lekei, E. E., Ngowi, A. V., & London, L. (2014). Farmers’ knowledge, practices and injuries associated with pesticide exposure in rural farming villages in Tanzania. BMC Public Health, 14(1), 389–402. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-389

- Levesque, D. L., Arif, A. A., & Shen, J. (2012). Effectiveness of pesticide safety training and knowledge about pesticide exposure among hispanic farmworkers. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 54(12), 1550–1556. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45010006 https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0b013e3182677d96

- London, L. (2003). Human rights, environmental justice, and the health of farm workers in South Africa. International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health, 9(1), 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1179/107735203800328876

- Maani Hessari, N., & Petticrew, M. (2017). What does the alcohol industry mean by ‘responsible drinking’? A comparative analysis. Journal of Public Health, 40(1), 90–97. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdx040

- Maertens, A., Golden, E., & Hartung, T. (2021). Avoiding regrettable substitutions: Green toxicology for sustainable chemistry. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering, 9(23), 7749–7758. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.0c09435

- Mart, M. (2015). Pesticides, a love story: America’s enduring embrace of dangerous chemicals. University Press of Kansas.

- McCambridge, J., Mialon, M., & Hawkins, B. (2018). Alcohol industry involvement in policymaking: A systematic review. Addiction, 113(9), 1571–1584. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14216

- Mew, E. J., Padmanathan, P., Konradsen, F., Eddleston, M., Chang, S.-S., Phillips, M. R., & Gunnell, D. (2017). The global burden of fatal self-poisoning with pesticides 2006-15: Systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 219, 93–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.05.002

- Mialon, M., & McCambridge, J. (2018). Alcohol industry corporate social responsibility initiatives and harmful drinking: a systematic review. European Journal of Public Health, 28(4), 664–673. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cky065

- Mishara, B. (2005). Report on the International Workshop on Secure Access to Pesticides in Conjunction with the Annual Congress of the International Association for Suicide Prevention, Durban, South Africa.

- Molina-Guzmán, L. P., & Ríos-Osorio, L. A. (2020). Occupational health and safety in agriculture. A systematic review. Revista de la Facultad de Medicina, 68(4), 625–638. http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0120-00112020000400625&nrm=iso https://doi.org/10.15446/revfacmed.v68n4.76519

- Murray, D. L. (1994). Cultivating crisis: The human cost of pesticides in Latin America. University of Texas Press.

- Murray, D. L., & Taylor, P. L. (2000). Claim no easy victories: Evaluating the pesticide industry’s global safe use campaign. World Development, 28(10), 1735–1749. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(00)00059-0

- Naidoo, S., London, L., Rother, H.-A., Burdorf, A., Naidoo, R., & Kromhout, H. (2010). Pesticide safety training and practices in women working in small-scale agriculture in South Africa. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 67(12), 823–828. https://doi.org/10.1136/oem.2010.055863

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). (2015). Hierarchy of controls. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/hierarchy/default.html

- Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, UNEP. (n.d.). Human rights and hazardous substances: Key messages. https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Issues/ClimateChange/materials/KMHazardousSubstances25febLight.pdf

- Orozco, F. A., Cole, D. C., Forbes, G. A., Kroschel, J. R., Wanigaratne, S., & Arica, D. (2009). Monitoring adherence to the international code of conduct: Highly hazardous pesticides in central Andean agriculture and farmers’ rights to health. International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health, 15(3), 255–268. https://doi.org/10.1179/oeh.2009.15.3.255

- Patel, A., Dewan, A., & Kaji, B. (2012). Monocrotophos poisoning through contaminated millet flour. Arhiv za Higijenu Rada i Toksikologiju, 63(3), 377–383. https://doi.org/10.2478/10004-1254-63-2012-2158

- Pearson, M., Metcalfe, C., Jayamanne, S., Gunnell, D., Weerasinghe, M., Pieris, R., Priyadarshana, C., Knipe, D. W., Hawton, K., Dawson, A. H., Bandara, P., DeSilva, D., Gawarammana, I., Eddleston, M., & Konradsen, F. (2017). Effectiveness of household lockable pesticide storage to reduce pesticide self-poisoning in rural Asia: A community-based cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet, 390(10105), 1863–1872. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31961-X

- Pesticide Action Network Germany. (2016). Stop pesticide poisonings! A time travel through international pesticide policies.

- Pingali, P. L. (1995). Impact of pesticides on farmer health and the rice environment: An overview of results from a multidisciplinary study in the philippines. In P. L. Pingali & P. A. Roger (Eds.), Impact of pesticides on farmer health and the rice environment (pp. 3–21). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-0647-4_1

- Pretty, J. N. (2005). The pesticide detox: towards a more sustainable agriculture. (J. Pretty, Ed.). Routledge.

- Rengam, S., Serrana, M., Quijano, I.-I., Castillo, D., Ravindran, D. (2018). Of rights and poisons: Accountability of the agrochemical industry. https://panap.net/resource/of-rights-and-poisons-accountability-of-the-agrochemical-industry/

- Rosenthal, E. (2003). The tragedy of Tauccamarca: A human rights perspective on the pesticide poisoning deaths of 24 children in the Peruvian Andes. International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health, 9(1), 53–58. https://doi.org/10.1179/oeh.2003.9.1.53

- Rother, H.-A. (2010). Falling through the regulatory cracks: Street selling of pesticides and poisoning among urban youth in South Africa. International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health, 16(2), 202–213. https://doi.org/10.1179/107735210799160336

- Rother, H.-A. (2018). Pesticide labels: Protecting liability or health? – Unpacking “misuse” of pesticides. Current Opinion in Environmental Science & Health, 4, 10–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coesh.2018.02.004

- United Nations General Assembly. (1998). Rotterdam Convention on the prior informed consent procedure for certain hazardous chemicals and pesticides in international trade. p. 337 http://www.picint/TheConvention/Overview/TextoftheConvention/tabid/1048/language/en-US/Default.aspx

- Sarkar, S., Dias Bernardes Gil, J., Leeley, J., Mohring, N., Jansen, K. (2021). The use of pesticides in developing countres and their impact on health and the right to food (EP/EXPO/DEVE/FWC/2019-01/LOT3/R/06). (Directorate-General for External Policies. Policies Department, European Union). https://www.europarl.europa.eu/cmsdata/219887/Pesticides%20health%20and%20food.pdf

- Schilling, R. S. (1989). Health protection and promotion at work. British Journal of Industrial Medicine, 46(10), 683–688. https://doi.org/10.1136/oem.46.10.683

- Sharifzadeh, M. S., Damalas, C. A., & Abdollahzadeh, G. (2017). Perceived usefulness of personal protective equipment in pesticide use predicts farmers’ willingness to use it. The Science of the Total Environment, 609, 517–523. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.07.125

- Shattuck, A. (2021a). Generic, growing, green?: The changing political economy of the global pesticide complex. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 48(2), 231–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2020.1839053

- Shattuck, A. (2021b). Risky subjects: Embodiment and partial knowledges in the safe use of pesticide. Geoforum, 123, 153–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.04.029

- Shattuck, A. (2021c). Toxic uncertainties and epistemic emergence: Understanding pesticides and health in Lao PDR. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 111(1), 216–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2020.1761285