Abstract

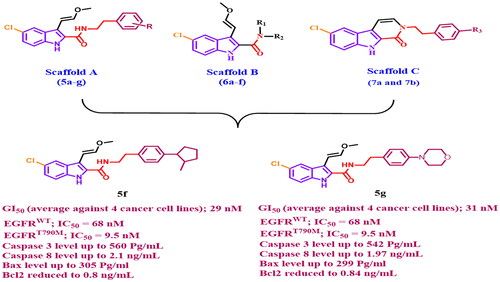

A new series of indole-2-carboxamides 5a-g, 6a-f and pyrido[3,4-b]indol-1-ones 7a and 7b have been developed as new antiproliferative agents that target both wild and mutant type EGFR. The antiproliferative effect of the new compounds was studied. 5c, 5d, 5f, 5 g, 6e, and 6f have the highest antiproliferative activity with GI50 values ranging from 29 nM to 47 nM in comparison to the reference erlotinib (GI50 = 33 nM). Compounds 5d, 5f, and 5 g inhibited EGFRWT with IC50 values ranging from 68 to 85 nM while the GI50 of erlotinib is 80 nM. Moreover, compounds 5f and 5 g had the most potent inhibitory activity against EGFRT790M with IC50 values of 9.5 ± 2 and 11.9 ± 3 nM, respectively, being equivalent to the reference osimertinib (IC50 = 8 ± 2 nM). Compounds 5f and 5 g demonstrated excellent caspase-3 protein overexpression levels of 560.2 ± 5.0 and 542.5 ± 5.0 pg/mL, respectively, being more active than the reference staurosporine (503.2 ± 4.0 pg/mL). they also increase the level of caspase 8, and Bax while decreasing the levels of anti-apoptotic Bcl2 protein. Computational docking studies supported the enzyme inhibition results and provided favourable dual binding modes for both compounds 5f and 5 g within EGFRWT and EGFRT790M active sites. Finally, in silico ADME/pharmacokinetic studies predict good safety and pharmacokinetic profile of the most active compounds.

Introduction

Cancer, defined as the uncontrolled, rapid, and pathological proliferation of abnormal cells, is the second leading cause of death after cardiovascular diseaseCitation1. Every year, cancer claims the lives of approximately 9.6 million peopleCitation2. While significant progress has been made in the development of anticancer drugs, there are still many barriers to cancer treatment, such as poor efficacy, high toxicity, and drug resistance, all of which have had a significant impact on patients’ daily livesCitation3. The search for active, safe anticancer compounds with high selectivity is thus a critical issue in contemporary cancer researchCitation4.

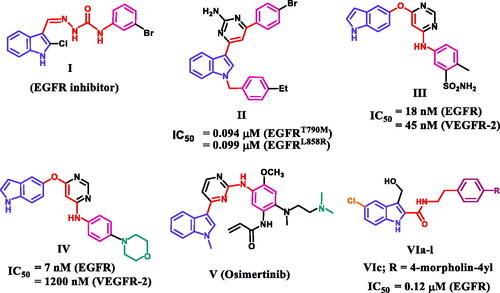

As a transmembrane-bound molecule, the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) regulates cell proliferation, apoptosis, migration, differentiation, and survivalCitation5. Increased EGFR activity caused by EGFR gene overexpression, mutation, or amplification contributes to many human cancers, including glioblastoma, epithelial cancers of the head and neck, breast cancers, and lung cancers, particularly non-small-cell lung cancers (NSCLCs)Citation6. As a result, blocking the EGFR signalling pathway, either extracellularly by blocking the EGFR binding site or intracellularly by inhibiting tyrosine kinase activity, is significant in cancer prevention and treatmentCitation7. Advanced EGFR mutant NSCLC patients’ survival has been significantly improved by first (gefitinib or erlotinib) and second (afatinib or dacomitinib)-generation EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) ()Citation8,Citation9. But the appearance of acquired point mutations, particularly the T790 M mutation, has reduced their therapeutic efficacy and resulted in drug resistanceCitation10. As a result, third-generation EGFR inhibitors targeting the T790 M mutation (osimertinib and rociletinib) have been developedCitation11. Unfortunately, the C797S point mutation and/or other mechanisms have been linked to acquired resistance to third-generation EGFR TKIsCitation12. As a result, fourth-generation EGFR TKIs such as EAI045 and other inhibitors are being developed to provide a significant breakthrough against this mutationsCitation13. However, the need for novel small molecule inhibitors or therapeutic strategies to treat EGFR multipoint mutations remains unfulfilled.

On the other hand, the indole skeleton, which can be found in many active ingredients and natural products, is one of the most popular structures with potent antitumor activityCitation14. Many indole derivatives are potent anticancer drugs thus far, and some of them have even been applied in clinicsCitation15–17. A large number of indole-based derivatives with TK inhibitory activity were also discovered in the literature reviewCitation18–21. Li et al. reported compound I to have potent anticancer activity against a panel of four cancer cell lines (IC50 = 1.43–5.48 µM)Citation18. A western blot mechanistic assay of compound I revealed promising EGFR inhibitory activity. Compound II was discovered to be a dual EGFR (T790M)/c-MET inhibitor capable of targeting resistant NSCLCCitation19. Compound II inhibited EGFR (T790M), EGFR (L858R), and c-MET with IC50 values of 0.094, 0.099, and 0.595 µM, respectively ().

Song et al. reported a series of indole derivatives as dual EGFR/VEGFR-2 inhibitorsCitation20. Compound III demonstrated dual inhibitory activities against EGFR and VEGFR-2, with IC50 values of 18 and 45 nM, respectively. Compound IV was also reported as a dual EGFR/VEGFR-2 inhibitor, with a prominent effect against EGFR compared to III, indicating the significance of morpholino moiety for EGFR inhibitory activity. Osimertinib (V) is an EGFR TKI with a selectivity index of about 200-fold towards EGFR T790M/L858R protein over wild-type EGFRCitation21. Because of its selectivity and activity, osimertinib was approved by the FDA in 2015 to treat EGFR T790M-positive NSCLCCitation21. We recentlyCitation22 reported on the development of a novel series of 5-chloro-3-hydroxymethyl-indole-2-carboxamides VIa-l () as EGFR-TK antiproliferative agents. The most potent antiproliferative agent, compound VIc (R = 4-morpholin-4-yl), demonstrated significant EGFR inhibitory activity with an IC50 value of 0.12 µM.

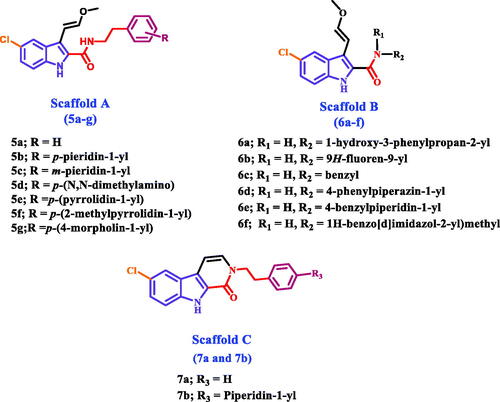

Herein, we present the synthesis and antiproliferative evaluation of a number of new 5-chloro-3–(2-methoxyvinyl)-indole-2-carboxamides 5a-g (Scaffold A), 6a-f (Scaffold B), and pyrido[3,4-b]indol-1-ones 7a and 7b (Scaffold C) derivatives as EGFR inhibitors (). In order to increase the binding affinities of the newly designed compounds towards the EGFR active sites, the new compounds were subjected to structural modifications, including the extension of the hydroxymethyl group at C3 of compounds VIa-l to methoxyvinyl group. The chlorine atom in position C8 of the new compounds was retained because it produces the best results when compared to the other groups. Furthermore, amidic NH and methoxyvinyl groups were cyclized to pyridine moiety in compounds 7a and 7b to evaluate the effect of cyclisation on the antiproliferative action of these compounds.

MTT assay was used to assess the antiproliferative activity of the target compounds against a panel of four different cancer cell lines [A-549 (epithelial cancer cell line), MCF-7 (breast cancer cell line), Panc-1 (pancreas cancer cell line), and HT-29 (colon cancer cell line)]. Furthermore, the most active compounds were tested for EGFR (EGFRWT and EGFRT790M) inhibitory activity. Additionally, apoptosis assays against caspase 3, caspase 8, Bax, and antiapoptotic Bcl2 have been accomplished for the most effective compounds. Finally, docking and ADME experiments for the most active compounds will be performed to determine their binding modes within the active sites of the target enzymes or to determine their pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic features.

Results and discussions

Chemistry

Scheme 1 describes the synthesis of target compounds 5a-g, 6a-f, 7a, and 7b. 5-chloro-3-formyl indole-2-carboxylate (1) was reacted with NaH and Di-tert-butyl dicarbonate [(Boc)2O] in DMF to afford the protect N-Boc indole (2)Citation23. The aldehyde (2) was treated with CH3OCH2P+(C6H5)3Cl- in the presence of potassium tert-butoxide in dry THF under Wittig reaction conditions to yield intermediate (3)Citation24. The trans (E) isomer of 3 was hydrolysed with aqueous NaOH to afford corresponding carboxylic acid (4)Citation25. The carboxylic acid (4) was coupled with appropriate amine derivatives using BOP as the coupling reagent in the presence of DIPEA in DCM to obtain carboxamides (5a-g and 6a-f). Carboxamides 5a and 5b were cyclised by PTSA in the reflux toluene to yield the desired pyrido[3,4-b]indol-1-one products 7a and 7b. NMR spectroscopy and mass spectral analysis were used to determine the structures of new compounds 5a-g, 6a-f, 7a, and 7b. The presence of additional peaks in the 1H and 13C NMR spectra of the new compounds distinguished them from the carboxylic acid starting material 4. In the 1H NMR spectrum of 5e (as a representative example), the disappearance of the acidic OH signal and the appearance of the amidic NH singlet signal at δ 6.60 ppm (1H) indicate amide formation. In addition, the 1H NMR spectrum of 5e revealed the characteristic signals of the methoxyvinyl group at 3-position in the form of two doublet signals of one proton each at δ 6.81 and δ 5.59 ppm corresponding to two vinyl protons (CH=CHOCH3). and a singlet signal of methyl protons at 3.52 ppm (CH = CHOCH3). The spectrum also showed two signals (each of 2H) at 3.77 (q) and 2.85 (t) ppm corresponding to NCH2CH2 group, as well as the pyrrolidinyl protons. The 13C NMR spectrum of 5e revealed two signals at δ 41.20 and δ 34.61 ppm for (NCH2CH2) and (NCH2CH2), respectively, as well as four additional carbon signals in the aromatic. HRESI-MS with [M + H]+ ion at m/z 424.1789 also validated the 5e structure.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of compounds 5a-g, 6a-f, 7a, and 7b. Reagents and conditions: (a) NaH, (Boc)2O, DMF, 0 °C to rt, overnight, 79%; (b) CH3OCH2P+(C6H5)3Cl-, t-BuOK, THF, 0 °C to rt, overnight, 76%; (c) 5% NaOH, EtOH, 40 °C, 93%; (d) Amine, BOP, DIPEA, DCM, rt, overnight; (e) PTSA, toluene, reflux, overnight.

Biology

Antiproliferative assay

Cell viability assay

A cell viability assay was performed on the MCF-10A (human mammary gland epithelial) cell line to investigate the effect of compounds 5a-g, 6a-f, 7a, and 7b on normal cell linesCitation26,Citation27. This study employs a concentration of 50 µM of the investigated compound for four days before assessing cell viability. Compounds 5a-g, 6a-f, 7a, and 7b have no toxic effect and have greater than 87% cell viability, as shown in .

Table 1. IC50 of compounds 5a-g, 6a-f, 7a, and 7b against four cancer cell lines.

Antiproliferative assay

The newly synthesised compounds 5a-g, 6a-f, 7a, and 7b were tested for antiproliferative activity against four different types of cancer cellsCitation28,Citation29: A-549 (epithelial cancer cell line), MCF-7 (breast cancer cell line), Panc-1 (pancreas cancer cell line), and HT-29 (colon cancer cell line). The results of calculating the IC50 of each compound using erlotinib as the reference are shown in .

In general, the newly investigated compounds 5a-g, 6a-f, 7a, and 7b demonstrated promising antiproliferative activity against the four cancer cell lines tested, with mean GI50 ranging from 29 nM to 102 nM against the four cancer cell lines when compared to the reference erlotinib, which had a GI50 of 33 nM. The compounds with the highest antiproliferative activity were 5c, 5d, 5f, 5 g (Scaffold A), 6e, and 6f (Scaffold B), with GI50 values ranging from 29 nM to 47 nM. With a GI50 of 29 nM, compound 5f (R = p-2-methyl pyrrolidin-1-yl, Scaffold A) was the most potent derivative, outperforming the reference erlotinib’s GI50 of 33 nM. Compound 5f suppressed all cancer cell lines more efficiently than erlotinib except HT-29 (colon cancer cell line). Compounds 5 g (R = p-4-morpholin-1-yl, Scaffold A) and 5d (R = p-N,N-dimethyl amino, Scaffold A) ranked second and third in activity, with GI50 values of 31 nM and 36 nM, respectively, and were comparable to the reference erlotinib against the four tested cancer cell lines. The unsubstituted derivative, 5a (R = H, Scaffold A), was 2.5-fold less potent than compound 5f, whereas compounds 5b (R = p-piperidin-1-yl, Scaffold A) and 5e (R = p-pyrrolidin-1-yl, Scaffold A) showed moderate antiproliferative action with GI50 values of 77 nM and 70 nM, respectively, indicating the significance of the para substitution on the phenethyl ring of compounds 5a-g, with activity increasing in the following order: 2-methyl pyrrolidine > 4-morpholine > N,N-dimethylamine > pyrrolidine > H > piperidine.

Compound 5c (R = m-piperidin-1-yl, Scaffold A) demonstrated good antiproliferative activity against the four tested cell lines, with a GI50 value of 47 nM, being 1.6-fold more potent than compound 5b (R = p-piperidin-1-yl, Scaffold A), indicating that the meta position of the phenethyl ring moiety may be tolerated for antiproliferative action than the para one. However, because only one meta-derivative (5c) is being prepared in the current study, this argument may require further investigation in the future.

Scaffold B compounds 6e (R1 = 4-benzylpiperidin-1-yl) and 6f (R1 = 1H-benzo[d]imidazole-2-yl)methyl) showed promising antiproliferative action with GI50 values of 45 nM and 41 nM, respectively, approximately 1.5-fold less potent than 5c. The remaining Scaffold B compounds 6a-d showed moderate to weak GI50 values ranging from 66 nM to 102 nM.

Finally, Scaffold C compounds 7a (R2 = H) and 7b (R2 = p-piperidin-1-yl) demonstrated greater antiproliferative activity than their open-form Scaffold A counterparts 5a and 5b. The GI50 values for 7a and 7b were 54 nM and 57 nM, respectively, compared to 76 nM and 77 nM for 5a and 5b, indicating that the cyclized 1H-pyrido[3,4-b]indol-1-ones 7a and 7b are more tolerated for antiproliferative activity than the uncyclized. 3–(2-methoxyvinyl)-1H-indole-2-carboxamides 5a and 5b. Unfortunately, only two 1H-pyrido[3,4-b]indol-1-one derivatives (Scaffold C) have been synthesised. However, more Scaffold C derivatives are required to obtain a precise SAR.

EGFR inhibitory assay

The six most potent antiproliferative derivatives (5c, 5d, 5f, 5 g, 6e, and 6f) were tested for inhibitory action against wild-type EGFR (EGFRWT)Citation30,Citation31 as a potential target for their antiproliferative activity. Results are presented as IC50 values in . The results of this assay are consistent with those of the antiproliferative assay, in which the most potent antiproliferative derivatives, compounds 5f (R = p-2-methyl pyrrolidin-1-yl, Scaffold A) and 5 g (R = p-4-morpholin-1-yl, Scaffold A), were the most potent EGFRWT inhibitors, with IC50 values of 68 ± 5 nM and 74 ± 5 nM, respectively, being more potent than the reference erlotinib (IC50 = 80 ± 5). Compound 5d (R = p-N,N-dimethylamino, Scaffold A) is the third most active compound, with an IC50 value of 85 ± 5, which is equivalent to erlotinib.

Table 2. IC50 of compounds 5c, 5d, 5f, 5 g, 6e, and 6f against EGFRWT and EGFRT790M.

Compounds 5c (R = m-piperidin-1-yl, Scaffold A), 6e (R1 and R2 = 4-benzylpiperidin-1-yl, Scaffold B) and 6f (R1 = H, R2 = 1H-benzo[d]imidazole-2-yl)methyl, Scaffold B) exhibited moderate anti-EGFR activity with IC50 values of 102 ± 7 nM, 98 ± 07 nM, and 93 ± 06, respectively being less potent than erlotinib. These findings demonstrated that compounds 5f and 5 g have potent EGFRWT inhibitory activity and are potential antiproliferative candidates.

The inhibitory activity of the most potent compounds, 5f and 5 g, against mutant-type EGFR (EGFRT790M) was assessed using the HTRF KinEASE-TK assayCitation30,Citation31, with Osimertinib as the positive control. Compounds 5f and 5 g, as shown in , had excellent inhibitory activity against EGFRT790M, with IC50 values of 9.5 ± 2 and 11.9 ± 3 nM, respectively, being equivalent to the reference osimertinib (IC50 = 8 ± 2 nM), which may explain their potent antiproliferative activity. These findings suggested that 2-methyl pyrrolidine and morpholine substitutions in the para-position of the phenethyl moiety are essential for the inhibitory effect on EGFRT790M.

Apoptotic marker assays

The development of novel medications that target apoptosis has become vitally important for clinical application since aberrations in apoptosis in cancer cells represent the main obstacle to the therapeutic efficacy of anticancer treatmentsCitation32. Compounds 5f and 5 g were evaluated for their ability to initiate the apoptosis cascade in order to reveal their proapoptotic potential.

Caspase-3 assay

Caspases have an important role in the induction and completion of apoptosisCitation33. Among caspases, caspase-3 is an important caspase that cleaves various proteins in cells, resulting to apoptosisCitation34. Compounds 5f and 5 g, the most potent derivatives, were tested as caspase-3 activators against pancreatic cancer cell line (Panc-1)Citation32, and the results are shown in . Compounds 5f and 5 g demonstrated excellent caspase-3 protein overexpression levels of 560.2 ± 5.0 and 542.5 ± 5.0 pg/mL, respectively. They increased the protein caspase-3 in the Panc-1 human pancreatic cancer cell line by approximately 8 times when compared to control untreated cells, and they were even more active than the reference staurosporine (503.2 ± 4.0 pg/mL). These results indicate that the tested compounds act as caspase-3 activators and can therefore be regarded as apoptotic inducer agents.

Table 3. Caspase-3 level for compounds 5f, 5 g, and staurosporine in human pancreatic cancer cell line (Panc-1).

Caspase 8, Bax, and Bcl-2 assay

Compounds 5f and 5 g were further examined for their effect on caspase-8, Bax, and Bacl-2 levels against the human pancreatic cancer cell line (Panc-1)Citation32 using staurosporine as a reference, as presented in . The results showed that 5f and 5 g significantly raised the levels of caspase-8 and Bax when compared to staurosporine.

Table 4. Caspase-8, Bax and Bcl-2 levels for compounds 5f, 5 g and staurosporine on human pancreatic cancer cell line (Panc-1).

Compound 5f had the maximum level of caspase-8 overexpression (2.10 ng/mL), followed by 5 g (1.97 ng/mL), and reference staurosporine (1.75 ng/mL). 5f and 5 g elevated the caspase-8 level by 25-folds and 23-folds, respectively in comparison to the control untreated cell.

Additionally, in comparison to untreated Panc-1 cancer cells, compounds 5f and 5 g produced 37- and 36-fold higher levels of Bax induction (305 pg/mL and 299 pg/mL, respectively) than staurosporine (276 pg/mL, a 33-fold induction). Finally, compounds 5f and 5 g induced equipotent down-regulation of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 protein levels in the Panc-1 cell line when compared to staurosporine.

Molecular modeling

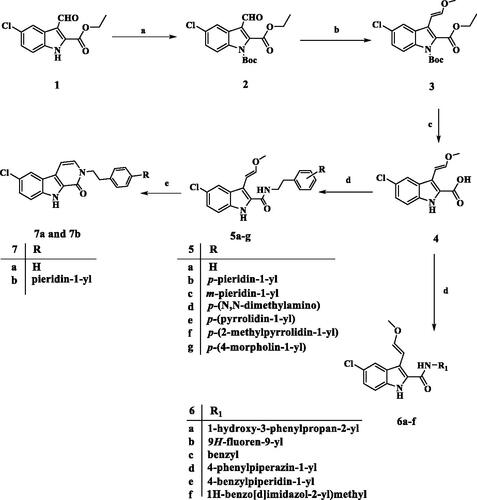

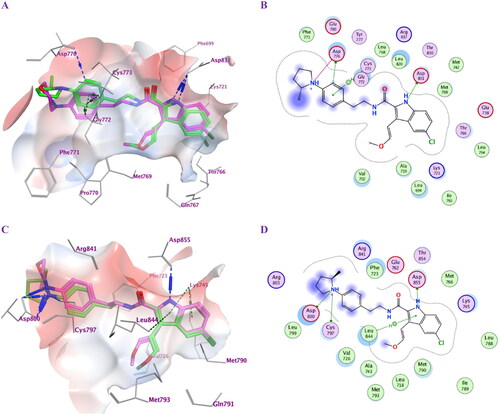

The most active antiproliferative compounds (5c, 5d, 5f, 5 g, 6e, and 6f) were subjected to in silico docking study with the aim of studying their binding modes within EGFRWT active site. Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) softwareCitation35 was used along with the crystal structure of the wild-type EGFRWT (PDB: 1M17)Citation36. According to the prior reportCitation37,Citation38, ligand and protein files were prepared into the pdbqt format. The accuracy of docking simulation within the binding site of EGFR was validated via redocking the co-crystallized ligand showing S score of −9.37 kcal/mol with RMSD value of 1.39 Å, (S1) (). Analysis of the binding score amongst the examined compounds revealed that compounds 5f and 5 g showed the highest negative scores (-9.88 and −9.47 kcal/mol, respectively) comparable to the co-crystalized ligand. Binding mode analysis revealed that all compounds tested fit comfortably within the large active site. Compounds 5d, 5f and 5 g with (R = p-N,N-dimethyl amino, p-2-methylpyrrolidin-1-yl and p-4-morpholin-1-yl moieties), respectively, exhibited better binding conformations within the binding pocket than compounds 5c, 6e and 6f. Compounds 5f and 5 g showed almost similar binding modes. The indolyl NH of 5f and 5 g ligands donates an H-bond to the key amino acid Asp831 (3.25 and 3.19 Å, respectively). Also, they formed additional π-H interactions with Cys773 and Gly772 (). Moreover, the p-2-methyl pyrrolidin-1-yl moiety of compound 5f forms an ionic bond (4.00 Å) as well as donates an H-bond (3.40 Å) to the amino acid residue Asp776 at the gate of the active site. The later interaction augments the binding pattern of compound 5f over compound 5 g. Both compounds exhibited comparable hydrophobic interactions and fulfilled the electrostatic interaction surface of the protein binding site (). Compound 5d exhibited also good binding mode but with different orientation within the EGFR active site. Compound 5d extends deeply into the hydrophobic pocket with its p-N,N-dimethylamino phenyl moiety forming ionic interaction with Glu738 (3.69 Å). The complex also is stabilised by accepting H-bond interaction from the key amino acid Met769 (2.84 Å) residue to the ligand amidic carbonyl group. In addition, the ligand forms pi-H interaction with Leu694 from the 5-chloro-indolyl moiety which projects parallel to the erlotinib ether chain. Compounds 5c and 6e resemble compounds 5f and 5 g in their binding modes, however losing interaction with Asp766 at the opening of the active site. Furthermore, compound 6f probes the space of the active site in an analogous pattern to that of compound 5d while missing interaction with the amino acid residue Glu738 at the hydrophobic pocket. Other ligands interactions within the active site include hydrophobic ones with Leu694, Leu820, Val702, Gly722, Thr766 and Phe771.

Figure 3. Docking representation models for compounds 5f and 5 g; (A) 3D-docked models of compound 5f (green) aligned with 5 g (purple) within the active site of EGFRWT showing the interaction surface of the protein (electrostatics; green: hydrophobic, blue; positive and red: negative); (B) 2D-docked model of compound 5f within the active site of EGFRWT; (C) 3D-docked models of compound 5f (green) aligned with 5 g (purple) within the active site of EGFRT790M showing the interaction surface of the protein (electrostatics; green: hydrophobic, blue; positive and red: negative); (D) 2D-docked model of compound 5f within the active site of EGFRT790M.

Table 5. Ligand-protein complex interactions of the tested compounds 5c, 5d, 5f, 5 g, 6e and 6f within the active site of EGFRWT.

The most potent compounds 5f and 5 g were further subjected to a docking study within the active pocket of the EGFR mutant type T790M for a deep understanding of their inhibition mode using the crystal structure of protein entry (PDB: 5J9Z)Citation39 for a deep understanding of their inhibition mode. The docking protocol was validated by redocking the co-crystallized ligand that exhibited S score of −10.42 kcal/mol with RMSD value of 0.88 Å, (S2). Compounds 5f and 5 g showed good negative scores (–9.43 and −9.31 kcal/mol) () comparable to the co-crystalized ligand although they did not bind in a covalent fashion. The ligand 5-chloro-indolyl moiety is inserted deeply inside the hydrophobic pocket where the indolyl NH donates an H-bond interaction to the amino acid Asp855 (2.99 and 3.01 Å). Also, their quaternary amine moieties form ionic bonds (2.98 and 2.94 Å) as well as H-bond interactions with Asp800 (3.31 and 3.17 Å) at the gate of the binding site. Moreover, the compounds formed additional π-H and π-cation interactions with Leu844 and Lys745, respectively, although they missed interactions with Met790, Gln791 and Met793 amino acid residues at the hydrophobic pocket. (). They exhibited comparable hydrophobic interactions with Asp800, Phe723, Leu844, Cys797, Leu718, Val726, Met790, Lys745 that strengthen the stability of the complexes within the protein binding site. The docking simulations tried to examine the binding mode of the most active compounds within the binding site of wild-type EGFR as well as EGFR mutant type T790M and confirmed the dual inhibitory effects of compounds 5f and 5 g.

Table 6. Ligand-protein complex interactions of the tested compounds 5f and 5 g within the active site of EGFRT790M.

In silico ADME/pharmacokinetics studies

The most potent compounds 5f and 5 g were subjected to in silico ADME studies using the web tool SwissADMECitation40 by entering a list of two compounds’ SMILES (Simplified Molecule Input Line Entry Specification) provided by ChemDraw software. The in silico pharmacokinetic data () showed that both compounds are orally active as they obey Lipinski’s rules of five with zero violation. Both compounds are actively effluxed by P-gp and exhibit high intestinal absorbance. Also, both compounds are capable to cross BBB. Drug permeability is a significant parameter that predicts the destiny of a drug. Based on Lipinski’s rules, it should be ≤ 5. Both compounds exhibited good permeability as indicated by logP values of 4.68 and 3.83. Only compound 5f is likely to be metabolised by CYP1A2 while both compounds are going to be CYP2D6, CYP3A4, CYP2C19 and CYP2C9 inhibitors. The results predict that both compounds exhibit good Pharmacokinetics and ADME properties ( and ).

Table 7. Physicochemical and pharmacokinetic properties (Lipinski parameters) of compounds 5f and 5 g.

Table 8. ADME properties of compounds 5f and 5 g.

Conclusion

A new series of 5-chloro-3–(2-methoxyvinyl)-indole-2-carboxamide and pyrido[3,4-b] Indol-1-one derivatives were synthesised and structurally characterised utilising several spectroscopic methods of analysis. The compounds had no cytotoxic effects on normal cell lines but showed promising antiproliferative properties against four human cancer cell lines. Some of the compounds tested showed potent inhibitory activity against both wild-type and mutant-type EGFR, as well as apoptotic-inducing activity. In silico docking studies attempted to explore the binding mode of the most active antiproliferative compounds within the binding site of EGFRWT-TK. Results proved the best binding modes for compounds 5f and 5 g that confirmed their highest potency compared to erlotinib. Also, docking results of both compounds against EGFRT790M conclude that addressing the hydrophobic pocket that comprises the Met790 amino acid with lipophilic scaffold may explain their affinity owing to reduced interactions with the polar Thr790 in EGFRWT. In silico ADME and pharmacokinetic prediction validated that the most potent compounds 5f and 5 g have good bioavailability and pharmacokinetic profiles. After structural modifications, 5f and 5 g may act as anticancer agents targeting EGFRT790M, but more in vitro and in vivo testing is required.

Experimental

General details: See Appendix A (Supplementary File)

Chemistry

Synthesis of 1-tert-butyl 2-ethyl 5-chloro-3-formyl-1H-indole-1,2-dicarboxylate (2)

A solution of indole ester 1 (1 g, 3.97 mmol) in DMF (0.2 M) was added dropwise at 0 °C to a suspension of NaH (0.25 g, 5.96 mmol, 60% dispersion in mineral oil) in DMF (0.2 M). After stirring 0.5 h, the resulting mixture was treated dropwise with (Boc)2O (1.34 g, 5.96 mmol). The cooling bath was removed, and the mixture was stirred overnight at rt. The reaction mixture was diluted with EtOAc and successively washed twice with water. EtOAc layer was washed with brine, dried over MgSO4, and concentrated under reduced pressure to yield compound 2 (1.1 g, 71%) as a white solid after purification by flash chromatography on silica gel using a mixture of EtOAc, hexanes (1:10) as eluent; mp 58–59 °C.

ν max (KBr disc)/cm−1 2983, 2939, 2872, 1750 (C = O), 1721 (C = O), 1670 (C = O), 1555, 1443, 1384, 1225, 1150, 840, 802, 764, 697. 1H NMR (250 MHz, CDCl3): δ 10.11 (1H, s, CHO); 8.29 (1H, s); 7.95 (1H, d, J = 8.8 Hz); 7.39 (1H, d, J = 9.3 Hz); 4.49 (2H, q, J = 7.0 Hz); 1.60 (9H, s); 1.43 (3H, t, J = 7.0 Hz). 13C NMR (62.5 MHz, CDCl3): δ (62.5 MHz, CDCl3): δ 185.6; 160.7; 147.9; 138.9; 133.9; 131.1; 127.7; 125.8; 122.5; 119.9; 116.0; 87.2; 63.0; 27.8; 14.2. HRESI-MS m/z calcd for [M + H]+ C17H19ClNO5: 352.0946, found: 352.0950.

Synthesis of (E)-1-tert-butyl 2-ethyl 5-chloro-3–(2-methoxyvinyl)-1H-indole-1,2-dicarboxylate (3)

To a stirred suspension of CH3OCH2P+(C6H5)3Cl- (2.17 g, 3 equiv) in anhydrous THF (20 ml) at 0 °C under N2 atmosphere, t-BuOK (2.17 g, 3 equiv) was added. The resulting mixture was stirred for additional 10 min at 0 °C before treating dropwise with a solution of 2 (0.74 g, 2.10 mmol, 1 equiv) in THF (20 ml). The cooling bath was removed, and the mixture was stirred overnight at rt. After concentration of the solvent in vacuo, the residue was taken up in EtOAc, washed with saturated solution of NaHCO3, brine, dried over MgSO4, and concentrated under reduced pressure. Flash chromatography of the crude product using (1:10) EtOAc/hexanes provided 3 (E) (0.53 g, 66%) as a white solid; mp 98–99 °C which was used for alkaline hydrolysis step and cis (Z) isomer (0.12 g, 15%) as a yellow oil.

Compound 3 (E): ν max (KBr disc)/cm−1 2981, 2935, 1729 (C = O), 1710 (C = O), 1635 (C = C), 1532, 1447, 1353, 1209, 1123, 1123, 962, 827, 777, 642. 1H NMR (250 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.00 (1H, d, J = 6.3 Hz); 7.65 (1H, s); 7.32 (1H, d, J = 9.3 Hz); 7.23 (1H, d, J = 13.5 Hz); 5.98 (1H, d, J = 13.3 Hz); 4.34 (2H, q, J = 7.0 Hz); 3.68 (3H, s); 1.60 (9H, s); 1.34 (3H, t, J = 7.0 Hz). 13C NMR (62.5 MHz, CDCl3): δ 162.5; 152.5; 149.1; 135.2; 128.9; 128.3; 126.9; 121.1; 120.7; 116.3; 94.5; 84.9; 61.5; 56.5; 53.5; 27.9; 14.2. HRESI-MS m/z calcd for [M + H]+ C19H23ClNO5: 380.1259, found: 380.1261.

Synthesis of (E)-5-Chloro-3–(2-methoxyvinyl)-1H-indole-2-carboxylic acid (4)

To a solution of compound 3 (trans isomer) (0.67 g, 1.76 mmol) in ethanol, (0.5 M), 5% NaOH (9 ml, 5 equiv) was added. The reaction mixture was kept at 40 °C with stirring overnight. The residue after removal of ethanol under reduced pressure was then taken into water, precipitated out at pH = 1 using 5% HCl and the precipitate extracted with EtOAc, dried over MgSO4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to afford 4 (0.41 g, 93%) as a pale-yellow solid; mp 132–134 °C.

ν max (KBr disc)/cm−1 33427 (NH), 3100 (br, OH), 2941, 1680 (C = O), 1643 (C = C), 1529, 1448, 1333, 1256, 1114, 929, 814, 796, 778. 1H NMR (250 MHz, CD3OD): δ 7.78 (1H, s); 7.48–7.10 (3H, m); 6.65 (1H, d, J = 13.3 Hz); 3.76 (3H, s). 13C NMR (62.5 MHz, CD3OD): δ 163.5; 149.8; 135.1; 125.6; 125.2; 124.9; 123.6; 120.5; 118.1; 113.2; 98.0; 55.2. HRESI-MS m/z calcd for [M + H]+ C12H11ClNO3: 252.0422, found: 252.0425.

Synthesis of compounds 5a-g and 6a-f

A mixture of indole-2-carboxylic acid 4 (0.52 mmol), BOP (0.34 g, 0.77 mmol), and DIPEA (0.17 ml, 1.03 mmol) in DCM (0.05 M) was stirred for 10 min at rt before addition of the appropriate amine (0.62 mmol), and the resulting reaction mixture was stirred overnight at rt. After removing of the solvent in vacuo, the residue was extracted with EtOAc, washed with 5% HCl, saturated NaHCO3 solution, brine, dried over MgSO4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to give a crude product which was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel using a mixture of EtOAc, hexanes (1:2) as an eluent.

(E)-5-Chloro-3–(2-methoxyvinyl)-N-phenethyl-1H-indole-2-carboxamide (5a)

Yield 76%; mp 150–152 °C; ν max (KBr disc)/cm−1 3257 (NH), 2950, 1650 (C = O), 1622 (C = C), 1637, 1451, 1218, 1163, 960, 801, 700; 1H NMR (250 MHz, CDCl3): δ 9.84 (s br, 1H, indole NH), 7.58 (s, 1H, Ar-H), 7.56–7.19 (m, 7H, Ar-H), 6.77 (d, J = 13.00 Hz, 1H, CH = CHOCH3), 6.59 (s br, 1H, amide NH), 5.54 (d, J = 13.00 Hz, 1H, CH=CHOCH3), 3.81 (q, J = 6.25 Hz, 2H, NHCH2CH2), 3.52 (s, 3H, OCH3), 2.95 (t, J = 6.25 Hz, 2H, NHCH2CH2); 13C NMR (62.5 MHz, CDCl3): δ 162.01 (C = O), 153.41, 138.75, 133.67, 128.94, 128.83, 128.11, 126.72, 126.03, 125.13, 120.04, 113.08, 111.31, 93.37, 56.71, 40.84, 35.64; HRESI-MS m/z calcd for [M + H]+ C20H20ClN2O2: 355.1208, found: 355.1211.

(E)-5-chloro-3–(2-methoxyvinyl)-N-(4-(piperidin-1-yl)phenethyl)-1H-indole-2-carboxamide (5b)

Yield 81%; mp 170–172 °C; ν max (KBr disc)/cm−1 3378 (NH), 3228 (NH), 2929, 2845, 1634 (C = O), 1620 (C = C), 1540, 1451, 1326, 1214, 1162, 1130, 959, 863, 804, 777, 693; 1H NMR (400 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 9.66 (s, 1H, indole NH), 7.59 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.33 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.21 (dd, J = 8.7, 2.0 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.11 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 6.89 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 6.79 (d, J = 13.0 Hz, 1H, CH = CHOCH3), 6.58 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H, amide NH), 5.59 (d, J = 13.0 Hz, 1H, CH=CHOCH3), 3.76 (q, J = 6.5 Hz, 2H, NHCH2CH2), 3.56 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.16–3.08 (m, 4H, piperidin-H), 2.86 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H, NHCH2CH2), 1.76–1.65 (m, 4H, piperidin-H), 1.63–1.52 (m, 2H, piperidin-H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, cdcl3) δ 161.86, 153.29, 151.07, 133.57, 129.28, 128.90, 128.85, 128.21, 125.96, 125.02, 119.98, 116.76, 112.98, 111.20, 93.42, 56.67, 50.67, 40.93, 34.63, 25.89, 24.27; HRESI-MS m/z calcd for [M + H]+ C25H29ClN3O2: 438.1943, found: 438.1943.

(E)-5-chloro-3–(2-methoxyvinyl)-N-(3-(piperidin-1-yl)phenethyl)-1H-indole-2-carboxamide (5c)

Yield 86%; mp 80–82 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.05 (s, 1H, indole NH), 7.59 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.36 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.25–7.15 (m, 2H, Ar-H), 6.85–6.75 (m, 3H, Ar-H, CH = CHOCH3), 6.70 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 6.66 (s, 1H, amide NH), 5.59 (d, J = 13.0 Hz, 1H, CH=CHOCH3), 3.81 (q, J = 6.7 Hz, 2H, NHCH2), 3.55 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.15–3.08 (m, 4H, piperidin-H), 2.91 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 2H, NHCH2CH2), 1.71–1.61 (m, 4H, piperidin-H), 1.60–1.50 (m, 2H, piperidin-H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 162.08 (C = O), 153.26, 152.61, 139.40, 133.79, 129.36, 128.80, 128.12, 125.91, 125.02, 119.96, 119.30, 116.77, 114.59, 113.10, 111.37, 93.44, 56.64, 50.46, 40.87, 35.95, 25.80, 24.25; HRESI-MS m/z calcd for [M + H]+ C25H29ClN3O2: 438.1943, found: 438.1944.

(E)-5-chloro-N-(4-(dimethylamino)phenethyl)-3-(2-methoxyvinyl)-1H-indole-2-carboxamide (5d)

Yield 82%; mp 177–179 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.72 (s, 1H, indole NH), 7.59 (s, 1H, Ar-H), 7.34 (d, J = 8.7, Hz, 1H. Ar-H), 7.21 (dd, J = 8.7, 2.0 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.11 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 6.80 (d, J = 13.0 Hz, 1H, CH = CHOCH3), 6.71 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 6.59 (s, 1H, amide NH), 5.58 (d, J = 13.0 Hz, 1H, CH=CHOCH3), 3.76 (q, J = 66 Hz, 2H, NHCH2), 3.53 (s, 3H, OCH3), 2.93 (s, 6H, N(CH3)2), 2.85 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H, NHCH2CH2); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 161.87 (C = O), 153.27, 149.52, 133.60, 129.37, 128.88, 128.23, 126.26, 125.95, 125.00, 119.97, 113.02, 113.00, 111.22, 93.40, 56.56, 41.04, 40.68, 34.53; HRESI-MS m/z calcd for [M + H]+ C22H25ClN3O2: 398.1630, found: 398.1628.

(E)-5-chloro-3-(2-methoxyvinyl)-N-(4-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)phenethyl)-1H-indole-2-carboxamide (5e)

Yield 83%; mp 185 - 187 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.97 (s, 1H, indole NH), 7.59 (s, 1H, Ar-H), 7.35 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.21 (dd, J = 8.7, 2.0 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.09 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 6.81 (d, J = 13.0 Hz, 1H, CH = CHOCH3), 6.60 (s, 1H, amide NH), 6.53 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 5.59 (d, J = 13.0 Hz, 1H, CH=CHOCH3), 3.77 (q, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H, NHCH2), 3.52 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.30–3.22 (m, 4H, pyrrolidin-H), 2.85 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H, NHCH2CH2), 2.05–1.96 (m, 4H, pyrrolidin-H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 161.95 (C = O), 153.21, 146.85, 133.72, 129.44, 128.81, 128.28, 125.88, 124.93, 124.87, 119.93, 113.09, 111.94, 111.20, 93.47, 56.53, 47.64, 41.20, 34.61, 25.47; HRESI-MS m/z calcd for [M + H]+ C24H27ClN3O2: 424.1786, found: 424.1789.

(E)-5-chloro-3-(2-methoxyvinyl)-N-(4-(2-methylpyrrolidin-1-yl)phenethyl)-1H-indole-2-carboxamide (5f)

Yield 85%; mp 151–153 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.64 (s, 1H, indole NH), 7.59 (s 1H, Ar-H), 7.34 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.21 (dd, J = 8.7, 2.0 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.08 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 6.81 (d, J = 13.0 Hz, 1H, CH = CHOCH3), 6.62–6.51 (m, 3H, amide NH, Ar-H), 5.59 (d, J = 13.0 Hz, 1H, CH=CHOCH3), 3.88–3.70 (m, 3H, pyrrolidin-H, NHCH2), 3.52 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.41 (dd, J = 9.4, 7.3 Hz, 1H, pyrrolidin-H), 3.13 (m, 1H, pyrrolidin-H), 2.83 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H, NHCH2CH2), 2.13–1.93 (m, 3H, pyrrolidin-H), 1.71 (m, 1H, pyrrolidin-H), 1.17 (d, J = 6.2 Hz, 3H, CHCH3); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 161.82 (C = O), 153.24, 146.10, 133.56, 129.48, 128.87, 128.28, 125.93, 124.97, 124.66, 119.98, 112.97, 112.00, 111.19, 93.37, 56.48, 53.68, 48.27, 41.13, 34.55, 33.12, 23.31, 19.43; HRESI-MS m/z calcd for [M + H]+ C25H29ClN3O2: 438.1943, found: 438.1941.

(E)-5-chloro-3-(2-methoxyvinyl)-N-(4-morpholinophenethyl)-1H-indole-2-carboxamide (5 g)

Yield 87%; mp 180–182 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.50 (s, 1H, indole NH), 7.90 (t, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H, amide NH), 7.74 (s, 1H, Ar-H), 7.40 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.24–7.15 (m, 2H, Ar-H, CH = CHOCH3), 7.10 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 6.85 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 6.33 (d, J = 13.2 Hz, 1H, CH=CHOCH3), 3.73–3.66 (m, 4H, morph-H), 3.63 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.48 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H, NHCH2), 3.06–2.98 (m, 4H, morph-H), 2.76 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H, NHCH2CH2); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 161.87 (C = O), 150.14, 149.96, 134.58, 130.36, 129.58, 128.80, 126.50, 124.82, 124.30, 120.57, 115.70, 114.20, 113.14, 97.73, 66.57, 56.68, 49.13, 41.26, 34.63; HRESI-MS m/z calcd for [M + H]+ C24H27ClN3O3: 440.1735, found: 440.1737.

(E)-5-chloro-N-(1-hydroxy-3-phenylpropan-2-yl)-3-(2-methoxyvinyl)-1H-indole-2-carboxamide (6a)

Yield 80%; mp 152–154 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.41 (s, 1H, indole NH), 7.58 (s, 1H, Ar-H), 7.35–7.18 (m, 7H, Ar-H), 6.93 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 6.82 (d, J = 13.0 Hz, 1H, CH = CHOCH3), 5.67 (d, J = 13.0 Hz, 1H, CH=CHOCH3), 4.44–4.40 (m, 1H, NHCH), 3.86–3.71 (m, 2H, CH2OH), 3.68 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.01 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H, CHCH2), 2.56 (t, J = 5.3 Hz, 1H, OH); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 162.19 (C = O), 153.47, 137.42, 133.58, 129.20, 128.82, 128.73, 127.75, 126.80, 126.12, 125.29, 120.08, 112.93, 111.93, 93.43, 64.06, 56.67, 53.09, 37.17; HRESI-MS m/z calcd for [M + H]+ C21H22ClN2O3: 385.1313, found: 385.1313.

(E)-5-chloro-N-(9H-fluoren-9-yl)-3-(2-methoxyvinyl)-1H-indole-2-carboxamide (6b)

Yield 86%; mp 240–241 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.46 (s, 1H, indole NH), 8.59 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H, amide NH), 7.88 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.81 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.61 (q, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.48–7.32 (m, 5H, Ar-H), 7.28 (d, J = 13.3 Hz, 1H, CH = CHOCH3), 7.21 (dd, J = 8.7, 2.0 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 6.65 (d, J = 13.3 Hz, 1H, CH=CHOCH3), 6.25 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, NHCH), 3.66 (s, 3H, OCH3); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 162.73 (C = O), 149.92, 145.08, 140.63, 134.74, 128.94, 128.12, 127.76, 126.13, 125.50, 124.91, 124.62, 120.84, 120.66, 114.91, 114.21, 98.52, 56.61, 54.85; HRESI-MS m/z calcd for [M + H]+ C25H20ClN2O2: 415.1208, found: 415.1209.

(E)-N-benzyl-5-chloro-3-(2-methoxyvinyl)-1H-indole-2-carboxamide (6c)

Yield 82%; mp 170–172 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.82 (s, 1H, indole NH), 7.60 (d, J = 2.0, Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.41–7.16 (m, 7H, Ar-H), 6.95 (s, 1H, amide NH), 6.85 (d, J = 13.0 Hz, 1H, CH = CHOCH3), 5.81 (d, J = 13.0 Hz, 1H, CH=CHOCH3), 4.71 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H, NHCH2), 3.63 (s, 3H, OCH3); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 161.99 (C = O), 153.45, 137.85, 133.73, 128.86, 128.85, 127.91, 127.71, 127.58, 126.06, 125.20, 120.00, 113.09, 111.53, 93.80, 56.75, 43.85; HRESI-MS m/z calcd for [M + H]+ C19H18ClN2O2: 341.1051, found: 341.1053.

(E)-(5-chloro-3–(2-methoxyvinyl)-1H-indol-2-yl)(4-phenylpiperazin-1-yl) methanone (6d)

Yield 78%; mp 102–104 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.98 (s, 1H, indole NH), 7.68 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.33–7.23 (m, 3H, Ar-H), 7.21–7.14 (m, 1H, Ar-H), 7.00 (d, J = 13.0 Hz, 1H, CH = CHOCH3), 6.96–6.86 (m, 3H, Ar-H), 5.87 (d, J = 13.0 Hz, 1H, CH=CHOCH3), 3.81 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 4H, piperazin-H), 3.72 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.16 (t, J = 5.2 Hz, 4H, piperazin-H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 164.47 (C = O), 150.75, 150.13, 134.78, 129.29, 126.91, 126.50, 125.92, 124.40, 120.71, 119.96, 116.74, 113.07, 111.86, 96.45, 56.88, 49.74; HRESI-MS m/z calcd for [M + H]+ C22H23ClN3O2: 396.1473, found: 396.1474.

(E)-(4-benzylpiperidin-1-yl)(5-chloro-3–(2-methoxyvinyl)-1H-indol-2-yl) methanone (6e)

Yield 79%; mp 95–97 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.74 (s, 1H, indole NH), 7.65 (s, 1H, Ar-H), 7.33–7.07 (m, 7H, Ar-H), 6.96 (d, J = 13.0 Hz, 1H, CH = CHOCH3), 5.82 (d, J = 13.0 Hz, 1H, CH=CHOCH3), 3.72 (s, 3H, OCH3), 2.89–2.85 (m, 2H, piperidin-H), 2.53 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H, CHCH2), 1.84–1.65 (m, 4H, piperidin-H), 1.31–1.14 (m, 3H, piperidin-H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 164.17 (C = O), 149.75, 139.73, 134.60, 129.05, 128.32, 127.61, 126.53, 126.10, 125.77, 124.09, 119.84, 112.93, 111.31, 96.61, 56.82, 42.86, 38.16, 32.27; HRESI-MS m/z calcd for [M + H]+ C24H26ClN2O2: 409.1677, found: 409.1678.

(E)-N-((1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)methyl)-5-chloro-3–(2-methoxyvinyl)-1H-indole-2-carboxamide (6f)

Yield 80%; mp 205–207 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.33 (s, 1H, indole NH), 11.60 (s, 1H, imidazol NH), 8.52 (t, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H, amide NH), 7.79 (s, 1H, Ar-H), 7.53–7.40 (m, 3H, Ar-H), 7.31–7.19 (m, 1H, Ar-H), 7.16– 7.12 (m, 2H, Ar-H), 6.54 (d, J = 13.2 Hz, 1H, CH=CHOCH3), 4.74 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 2H, NHCH2), 3.70 (s, 3H, OCH3); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 162.11 (C = O), 152.47, 150.45, 134.76, 128.08, 126.44, 124.92, 124.60, 121.94, 120.74, 114.28, 114.17, 97.79, 56.65, 38.01; HRESI-MS m/z calcd for [M + H]+ C20H18ClN4O2: 381.1113, found: 381.1113.

Synthesis of compounds 7a and 7b

A mixture of 5a or 5b (0.32 mmol, 1equiv) and PTSA (0.03 g, 0.5 equiv) in toluene (20 ml) was refluxed with stirring overnight. After concentration of the solvent in vacuo, the residue was extracted with EtOAc, washed with saturated solution of NaHCO3, brine, dried over MgSO4, and concentrated under reduced pressure to yield a crude product which purified by flash chromatography using EtOAc/hexanes (1:1) then EtOAc to yield 7a or 7b

6-chloro-2-phenethyl-2,9-dihydro-1H-pyrido[3,4-b]indol-1-one (7a)

Yield 88%; mp 265–267 °C; νmax (KBr disc)/cm−1 3114 (NH), 3029, 2954, 1652 (C = O), 1581, 1443, 1285, 1258, 805, 781, 745, 699; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.12 (s, 1H, indole NH), 8.11 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.49 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.38 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.1 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.29–7.12 (m, 6H, Ar-H, CH = CHN), 6.96 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H, CH=CHN), 4.25 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H, NCH2CH2), 2.99 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H, NCH2CH2); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO): δ 155.12 (C = O); 138.79 (C8a); 138.04 (C1’); 129.63 (C9a); 129.26 (C2’, 6′); 129.07 (C3); 128.84 (C3’, 5′); 126.83 (C4b); 126.72 (C4’); 124.39 (C6); 123.38 (C7); 123.23 (C5); 121.21 (C4a); 114.55 (C8); 100.16 (C4); 49.77 (NCH2CH2); 35.43 (NCH2CH2).

6-chloro-2–(4-(piperidin-1-yl)phenethyl)-2,9-dihydro-1H-pyrido[3,4-b]indol-1-one (7b)

Yield 81%; mp 293–295 °C; νmax (KBr disc)/cm−1 3129 (NH), 2936, 2850, 1657 (C = O), 1583, 1514, 1449, 1279, 1236, 1131, 810, 781, 754, 652; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.12 (s, 1H, indole NH), 8.14 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.52 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.41 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.1 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.27 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H, CH = CHN), 7.06 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 6.99 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H, CH=CHN), 6.83 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 4.22 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H, NCH2CH2), 3.10–3.03 (m, 4H, piperidin-H), 2.90 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H, NCH2CH2), 1.65–1.46 (m, 6H, piperidin-H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 155.08, 150.72, 138.02, 129.68, 129.65, 129.09, 128.47, 126.67, 124.36, 123.38, 123.20, 121.18, 116.35, 114.52, 100.06, 50.18, 50.03, 34.61, 25.71, 24.33; HRESI-MS m/z calcd for [M + H]+ C24H25ClN3O: 406.1681, found: 406.1676.

Biology

Appendix A has detailed information on all biological tests (Supplementary File)

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (4.7 MB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- You W, Henneberg M. Cancer incidence increasing globally: the role of relaxed natural selection. Evol Appl. 2018;11(2):140–152.

- Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424.

- Al-Sanea MM, Gotina L, Mohamed MF, Grace Thomas Parambi D, Gomaa HAM, Mathew B, Youssif BGM, Alharbi KS, Elsayed ZM, Abdelgawad MA, et al. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of new HDAC1 and HDAC2 inhibitors endowed with ligustrazine as a novel cap moiety. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2020;14:497–508.

- Youssif BGM, Gouda AM, Moustafa AH, Abdelhamid AA, Gomaa HAM, Kamal I, Marzouk AA. Design and synthesis of new triaryl imidazole derivatives as dual inhibitors of BRAFV600E/p38α with potential antiproliferative activity. J. Mol. Struct. 2022;1253:132218.

- Goffin JR, Zbuk K. Epidermal growth factor receptor: pathway, therapies, and pipeline. Clin Ther. 2013;35(9):1282–1303.

- Nadeem Abbas M, Kausar S, Wang F, Zhao Y, Cui H. Advances in targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor pathway by synthetic products and its regulation by epigenetic modulators as a therapy for glioblastoma. Cells. 2019;8(4):350–361.

- Tebbutt N, Pedersen MW, Johns TG. Targeting the ERBB family in cancer: couples therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13(9):663–673.

- Bhatia P, Sharma V, Alam O, Manaithiya A, Alam P, Alam MT, Imran M., Kahksha . Novel quinazoline-based EGFR kinase inhibitors: a review focusing on SAR and molecular docking studies (2015-2019). Eur J Med Chem. 2020;204:112640.

- Wright NMA, Goss GD. Third-generation epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2019;8(Suppl 3):S247–S264.

- Yu HA, Arcila ME, Rekhtman N, Sima CS, Zakowski MF, Pao W, Kris MG, Miller VA, Ladanyi M, Riely GJ, et al. Analysis of tumor specimens at the time of acquired resistance to EGFR-TKI therapy in 155 patients with EGFR-mutant lung cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(8):2240–2247.

- Walter AO, Sjin RTT, Haringsma HJ, Ohashi K, Sun J, Lee K, Dubrovskiy A, Labenski M, Zhu Z, Wang Z, et al. Discovery of a mutant-selective covalent inhibitor of EGFR that overcomes T790M-mediated resistance in NSCLC. Cancer Discov. 2013;3(12):1404–1415.

- Patel H, Pawara R, Ansari A, Surana S. Recent updates on third generation EGFR inhibitors and emergence of fourth generation EGFR inhibitors to combat C797S resistance. Eur J Med Chem. 2017;142:32–47.

- Shen J, Zhang T, Zhu S-J, Sun M, Tong L, Lai M, Zhang R, Xu W, Wu R, Ding J, et al. Structure-based design of 5- methylpyrimidopyridone derivatives as new wild-type sparing inhibitors of the epidermal growth factor receptor triple mutant (EGFR(L858R/T790M/C797S)). J Med Chem. 2019;62(15):7302–7308.

- Mishra RDLA. Anticancer potential of plants and natural products: a review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013;1:622–628.

- Youssif BGM, Abdelrahman MH, Abdelazeem AH, Abdelgawad MA, Ibrahim HM, Salem OIA, Mohamed MFA, Treambleau L, Bukhari SNA. Design, synthesis, mechanistic and histopathological studies of small-molecules of novel indole-2-carboxamides and pyrazino[1,2-a]indol-1(2H)-ones as potential anticancer agents effecting the reactive oxygen species production. Eur J Med Chem. 2018;146:260–273.

- Abdelrahman MH, Aboraia AS, Youssif BGM, Elsadek BEM. Design, Synthesis and Pharmacophoric Model Building of New 3-Alkoxymethyl/3-Phenyl indole-2-carboxamides with Potential Antiproliferative Activity. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2017;90(1):64–82.

- Al-Wahaibi LH, Gouda AM, Abou-Ghadir OF, Salem OIA, Ali AT, Farghaly HS, Abdelrahman MH, Trembleau L, Abdu-Allah HHM, Youssif BGM, et al. Design and synthesis of novel 2,3-dihydropyrazino[1,2-a]indole-1,4-dione derivatives as antiproliferative EGFR and BRAFV600E dual inhibitors. Bioorg Chem. 2020;104:104260.

- Li W, Qi Y‐Y, Wang Y‐Y, Gan Y‐Y, Shao L‐H, Zhang L‐Q, Tang Z‐H, Zhu M, Tang S‐Y, Wang Z‐C, et al. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of sorafenib derivatives containing indole (ketone) semicarbazide analogs as antitumor agents. J Heterocyclic Chem. 2020;57(6):2548–2560.

- Singh PK, Silakari O. Molecular dynamics guided development of indole based dual inhibitors of EGFR (T790M) and c-MET. Bioorg Chem. 2018;79:163–170.

- Song J, Yoo J, Kwon A, Kim D, Nguyen HK, Lee B-Y, Suh W, Min KH. Structure-Activity Relationship of Indole-Tethered Pyrimidine Derivatives that Concurrently Inhibit Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor and Other Angiokinases. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0138823.

- Zhang H. Three generations of epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors developed to revolutionize the therapy of lung cancer. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2016;10:3867–3872.

- Mohamed FAM, Gomaa HAM, Hendawy OM, Ali AT, Farghaly HS, Gouda AM, Abdelazeem AH, Abdelrahman MH, Trembleau L, Youssif BGM, et al. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of novel EGFR inhibitors containing 5-chloro-3-hydroxymethyl-indole-2-carboxamide scaffold with apoptotic antiproliferative activity. Bioorg Chem. 2021;112:104960.

- Mostafa HA, Alaa AKMH, Laurent KT. Synthesis and molecular docking of novel indole-2-carboxamide derivatives with anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive activities. J. Adv. Chem. 2014;10:3143–3159.

- Gomaa HAM, Shaker ME, Alzarea SI, Hendawy OM, Mohamed FAM, Gouda AM, Ali AT, Morcoss MM, Abdelrahman MH, Trembleau L, et al. Optimization and SAR investigation of novel 2,3-dihydropyrazino[1,2-a]indole-1,4-dione derivatives as EGFR and BRAFV600E dual inhibitors with potent antiproliferative and antioxidant activities. Bioorg Chem. 2022;120:105616.

- Youssif BGM, Mohamed AM, Osman EEA, Abou-Ghadir OF, Elnaggar DH, Abdelrahman MH, Treamblu L, Gomaa HAM. 5-chlorobenzofuran-2-carboxamides: from allosteric CB1 modulators to potential apoptotic antitumor agents. Eur J Med Chem. 2019;177:1–11.

- Mohassab AM, Hassan HA, Abdelhamid D, Gouda AM, Youssif BGM, Tateishi H, Fujita M, Otsuka M, Abdel-Aziz M. Design and Synthesis of Novel quinoline/chalcone/1,2,4-triazole hybrids as potent antiproliferative agent targeting EGFR and BRAFV600E kinases. Bioorg Chem. 2021;106:104510.

- Mekheimer RA, Allam SMR, Al-Sheikh MA, Moustafa MS, Al-Mousawi SM, Mostafa YA, Youssif BGM, Gomaa HAM, Hayallah AM, Abdelaziz M, et al. Discovery of new pyrimido[5,4-c]quinolines as potential antiproliferative agents with multitarget actions: Rapid synthesis, docking, and ADME studies. Bioorg Chem. 2022;121:105693.

- Ramadan M, Abd El-Aziz M, Elshaier YAMM, Youssif BGM, Brown AB, Fathy HM, Aly AA. Design and synthesis of new pyranoquinolinone heteroannulated to triazolopyrimidine of potential apoptotic antiproliferative activity. Bioorg Chem. 2020;105:104392.

- El-Sherief HAM, Youssif BGM, Abdelazeem AH, Abdel-Aziz M, Abdel-Rahman HM. Design, Synthesis and Antiproliferative Evaluation of Novel 1,2,4-Triazole/Schiff Base Hybrids with EGFR and B-RAF Inhibitory Activities. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2019;19(5):697–706.

- Abdel-Aziz SA, Taher ES, Lan P, Asaad GF, Gomaa HAM, El-Koussi NA, Youssif BGM. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of new pyrimidine-5-carbonitrile derivatives bearing 1,3-thiazole moiety as novel anti-inflammatory EGFR inhibitors with cardiac safety profile. Bioorg. Chem. 2021;111:104890.

- Zhang B, Liu Z, Xia S, Liu Q, Gou S. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of sulfamoyl phenyl quinazoline derivatives as potential EGFR/CAIX dual inhibitors. Eur J Med Chem. 2021;216:113300.

- Abou-Zied HA, Youssif BGM, Mohamed MFA, Hayallah AM, Abdel-Aziz M. EGFR inhibitors and apoptotic inducers: Design, synthesis, anticancer activity and docking studies of novel xanthine derivatives carrying chalcone moiety as hybrid molecules. Bioorg Chem. 2019;89:102997.

- Martin SJ. Caspases: executioners of apoptosis. Pathobiol Hum Dis. 2014;145:145–152.

- Rudel T. Caspase inhibitors in prevention of apoptosis. Herz. 1999;24(3):236–241.

- Chemical Computing Group ULC, 1010 Sherbooke St. West, Suite #910, Montreal, QC, Canada, H3A 2R7, 2020.

- Stamos J, Sliwkowski MX, Eigenbrot C. Structure of the epidermal growth factor receptor kinase domain alone and in complex with a 4-anilinoquinazoline inhibitor. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(48):46265–46272.

- Ibrahim TS, Bokhtia RM, Al-Mahmoudy AMM, Taher ES, AlAwadh MA, Elagawany M, Abdel-Aal EH, Panda S, Gouda AM, Asfour HZ, et al. Design, Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Novel 5-((substituted quinolin-3-yl/1-naphthyl)methylene)-3-substituted imidazolidin-2,4-dione as HIV-1 Fusion Inhibitors. Bioorg Chem. 2020;99:103782. [InsertedFromOnlin

- Shaykoon MS, Marzouk AA, Soltan OM, Wanas AS, Radwan MM, Gouda AM, Youssif BGM, Abdel-Aziz M. Design, synthesis and antitrypanosomal activity of heteroaryl-based 1,2,4-triazole and 1,3,4-oxadiazole derivatives. Bioorg Chem. 2020;100:103933.

- Engel J, Becker C, Lategahn J, Keul M, Ketzer J, Mühlenberg T, Kollipara L, Schultz-Fademrecht C, Zahedi RP, Bauer S, et al. Insight into the Inhibition of Drug-Resistant Mutants of the Receptor Tyrosine Kinase EGFR. Angew Chem Int Ed. (36)2016;55:10909–10912.

- Daina A, Michielin O, Zoete V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci Rep. 2017;7:42717.