ABSTRACT

Background

Pertussis remains as one of the oldest leading vaccine-preventable diseases of childhood, despite many decades of primary vaccine doses’ and boosters’ implementation. Although the epidemiology is well understood in infants and children, premature babies and low-birth weight infants remain a special group where the disease incidence is unknown, severity of the disease is considerable, and specific vaccination recommendations are scarce.

Research design and methods

A retrospective review of the available evidence of pertussis vaccination in premature and low birth weight infants was analyzed from January 2000 to December 2022 in six selected countries: Argentina, Mexico, Colombia, Panamá, Costa Rica, and Chile.

Results

Chile had reports of adverse effects associated with vaccination of premature infants with the pentavalent vaccine, and their rationale to switching to the hexavalent vaccine. Colombia had reports of the justification for the use of hexavalent vaccine in prematures in the Neonatal Units and Kangaroo Mother Programs throughout the country. Mexico had selected publications of the vaccination status in prematures and low-birth weight infants.

Conclusion

Despite its importance, increased morbidity, and highest risk of complications in premature babies, there is a paucity of information of vaccine recommendations and coverage rates among selected Latin American infants.

1. Introduction

Pertussis is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in young infants in countries with low vaccination coverages. Among vaccine-preventable diseases affecting young children, especially those less than 3 months of age, pertussis is the oldest and leading cause of deaths worldwide, especially in developing nations. Although the epidemiology of pertussis has been studied and described extensively around the world [Citation1] and in Latin America [Citation2–9], publications focusing on pertussis vaccination in premature babies are scarce, especially from developing nations. In fact, in Latin America, this issue has not been analyzed in detail and consequently was one on the motivations to perform this analysis in selective countries from our region. The main objective of this study was to describe the experience of six Latin American countries that utilized combined acellular pertussis vaccines in preterm infants. Other objectives of this review were to analyze the impact of COVID-19 pandemic in the vaccination of premature babies with the acellular pertussis vaccine in participant countries.

2. Methods

A retrospective review of the available evidence of pertussis from January 2000 to December 2022 was obtained from six selected countries: Argentina, Mexico, Colombia, Panamá, Costa Rica, and Chile.

Information from each country was provided by local pediatric infectious disease specialists and vaccine experts from the Sociedad Latinoamericana de Infectología Pediátrica (SLIPE) https://slipe.org/web/. Information was retrieved from scientific publications in indexed and non-indexed literature, expert opinions, and databases from each participant country.

Investigators were requested to provide retrospective information from their countries in terms of gestational age and age of the first dose of acellular pertussis vaccine, intervals between each dose, coadministration with other pediatric vaccines, underlying diseases or medical conditions in patients, safety date, acceptance of combined vaccines by parents and health-care professionals, and to determine if there was an increase or decrease in vaccine coverages since the time of introduction of these combined vaccines. There was also a particular interest to study when acellular pertussis vaccines introduced in each country, what is the percentage of premature deliveries, and survival rates in each country.

Due to the nature of this study and that no clinical charts were reviewed for this analysis, no ethical approval by an institutional review board or ethics committee was required.

3. Results

3.1. Argentina

In Argentina, vaccination against B. pertussis includes a primary schedule of acellular vaccine (2-4-6 months) and two whole-cell boosters (15–18 months and 4–6 years), one dose at 11 years with acellular component (since 2010), and in each pregnancy, from week 20 of gestation, with triple acellular bacterial vaccine (since 2012).

Vaccines against diphtheria, tetanus, whooping cough, Haemophilus influenzae b (Hib), hepatitis B, and poliomyelitis are administered to premature infants (gestational age less than 37 weeks) and babies with birth weight less than 1,500 g to reduce hospitalization, morbidity, and mortality from these diseases and minimize in this population the serious adverse effects triggered by the application of vaccines with cellular component against B. pertussis. The first vaccination is administered at the adjusted age of 2 months or upon reaching a weight of 2 kg and then continues on the regular schedule.

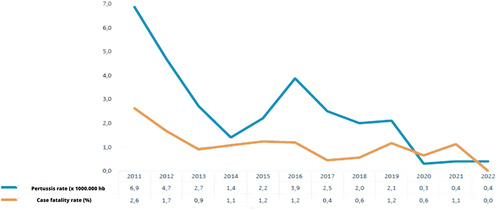

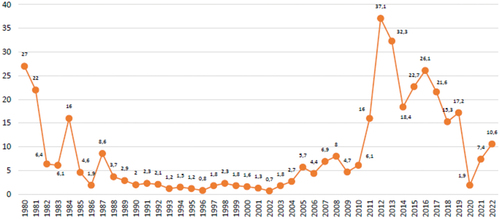

The reporting rate of suspected whooping cough cases over the past 39 years peaked in 2012. Since that year, an adequate sensitivity of the notification system has been observed, .

Figure 1. Pertussis: rate of notification of suspected cases per 100,000/inhabitants, Argentina, 1980–2022.

The higher mortality in recent years was coincidental with the peak incidence of the disease during the 2011–2012 season. During 2019, a total of 7870 suspected cases of pertussis were notified throughout the country to the Sistema Nacional de Vigilancia de la Salud (SNVS 2.0) (National Health Surveillance System), of which 975 cases (12.5%) were confirmed. The endemic corridor of cases during 2019 spent most of the period within the security area entering the alert zones between weeks 21–24, 36, and 45. During 2022, 4651 suspected pertussis cases were notified to the SNVS 2.0 in the country, of which 196 (4.2%) were confirmed. The highest incidence and mortality season was 2011–2012.

3.1.1. Incidence of pertussis, lethality, and vaccine coverage in Argentina (2011–2022)

Distribution by age showed that 65.3% of the confirmed cases occurred in children <1 year of age, and infants <1 month of life represented 5.6% of the cases; however, no information on how many patients were premature.

In , coverage rates against pertussis are shown. As seen, coverage rates decreased, and worsened after the initiation of COVID-19 pandemic.

3.1.2. Average interval between doses

In the case of maternal vaccination, acellular vaccine is indicated in each pregnancy, the dose of 11 years is unique, and in the case of premature infants, the regular schedule is recommended. Pertussis vaccines are administered according to the NIP and co-administration occurs when indicated.

In Argentina, vaccination in premature infants with acellular vaccine started in 2015, maternal vaccination in 2012, and vaccination in adolescents (single dose) in 2010. The hypothetical cohort includes 569,732 full-term births, 2,513 preterm births <28 weeks, 4,996 preterms between 28 and 32 weeks and 48,200 preterms between 32 and 36 weeks according to vital statistics from Argentina. There are no specific reports of safety and adverse events associated with pertussis vaccination in this specific age group. Nevertheless, and despite the absence of published data, acceptance of vaccines in premature patients by their parents is very high.

In this country, reports of adverse events of pediatric vaccination do not distinguish between preterm and term infants and are not registered separately. There is a vaccine safety committee (CONASEVA) that at this moment is focused more on COVID vaccines but at the time also attended and continues to do so the Events Supposedly Attributed to Vaccination or Immunization (ESAVI) in calendar.

3.2. Chile

The hexavalent combination vaccine administered to infants starting at 2 months of chronological age in Chile since 1 February 2018, provides protection against infections caused by Corynebacterium diphtheriae, Clostridium tetani, polio virus, Haemophilus influenzae type b, hepatitis B virus, and B. pertussis (with acellular component). It is given as a primary 3-dose schedule at 2, 4, 6 months with a booster at 18 months of age. Preterm (PT) and low birth weight (LBW) infants are known to have an increased susceptibility to Hib infection and B. pertussis mainly [Citation10].

In Chile, adverse events are registered as a whole age group event rather than events in prematures. A relevant situation that occurred in recent years in Chile was related precisely to the report of adverse effects associated with vaccination of premature infants with the pentavalent vaccine, which included a whole-cell pertussis component, where an increase in ESAVI was reported by the Vaccine Pharmacovigilance section of the Institute of Public Health of Chile [Citation11]. It was reported that the total number of ESAVI associated with pentavalent vaccine increased 85% when comparing the period January 2014–May 2015 and the period January 2016–May 2017, apneas increased by 31%, while in preterm patients, specifically, these registered an increase of 400%. Regarding this increase in ESAVI, the only change from one period to another corresponded to the pentavalent vaccine used in the country’s PNI (Quinvaxem®) pentavalent vaccine from Glaxo Smith Kline in the first period versus pentavalent vaccine of the Serum Institute of India in the second period). These facts, among other reasons, motivated the Advisory Committee on Vaccination and Immunizations (CAVEI, Ministry of Health, Chile) to recommend the incorporation of the hexavalent combined vaccine, with acellular pertussis component, in a 4-dose scheme (2, 4, 6, and 18 months) progressively, starting the doses of 2 and 4 months in February 2018 and the remaining doses of 6 and 18 months in February 2019 [Citation12]. With this, the Chilean National Immunization Program aligned itself with the WHO’s global polio eradication strategy, implementing a complete schedule with intramuscular polio vaccine, and concomitantly, a decrease in the rates of ESAVI in premature population was observed in association with the pentavalent vaccine during the period 2016–2017. Specifically, after the introduction of the hexavalent combination vaccine in the Chilean NIP, a 67% reduction was observed in the notification rate of ESAVI between 2016 and 2019 in relation to vaccines that contain DTP, especially in the group of premature infants. According to a recent communication, in this period [Citation13] there were 38 ESAVI in prematures, 16 associated with the whole-cell component pertussis vaccine, 13 with the acellular vaccine, and 9 cases in which no information was obtained. In cases associated with the whole-cell component-associated vaccine, 75% of ESAVIs were serious (n = 12), while for vaccines with acellular component it was 8%. In a recent study by Aguirre-Boza et al. [Citation14] regarding the ESAVI associated with pertussis vaccination, it was observed that the total number of notifications was 1,697, of which 815 corresponded to whole-cell vaccines, 417 to acellular pertussis component vaccines, and 465 of unknown type. The reporting rates for the years 2015 to 2020 were 40.1, 56.2, 37.1, 24.7, 19.1, and 12.2 per 100,000 doses administered, respectively. The most reported EAPVs were injection site erythema (42%), pyrexia (35%), and injection site pain (29%). Among all cases, 5.8% were SAE (n = 98), 5.9% were SAE for whole-cell pertussis vaccines (n = 48), and 5.3% were for acellular pertussis vaccines (n = 22). Therefore, a significant decrease in ESAVI reports was observed since 2018, the year in which the hexavalent combination vaccine was introduced in the NIP in Chile.

In addition, prior to the implementation of the complete hexavalent vaccine scheme nationwide, the Sub Secretary of Public Health of the Ministry of Health of Chile, established on 5 May 2017 a special program for the vaccination of all premature newborns with less than 37 weeks of gestation in public and private maternities, administering them the hexavalent combination vaccine given at 2, 4, 6, and 18 months of chronological age given the observed increase in episodes of apnea and bradycardia in this population.

The overall vaccination coverage in the country at 2, 4, 6, and 18 months, respectively, is described ahead. Unfortunately, data on vaccination coverage in the preterm population of Chile are scarce and not publicly available. includes the vaccination coverage information for the combined hexavalent vaccine between 2018 and 2021, including the recent years of the COVID-19 pandemic (Source: National Immunization Registry 2018–2021, Ministry of Health, Chile).

Table 1. Pentavalent/Hexavalent vaccination coverage in Chile between 2018 and 2021 (in red: year 2020, March 3 start of the COVID-19 pandemic in the country).Preterm newborns and survival in Chile.

3.2.1. Preterm newborns and survival in Chile

In Chile, during the last two decades there has been a significant increase in preterm deliveries, ranging from 6.2% in 1991 to 8% in 2012. This finding is related to an increase in maternal age (>35 years) at first pregnancy (10.6% in 1991 to 16.6% in 2012) and therefore a higher relative risk of prematurity [Citation15]. In 2014, among 250,977 live births in the nation, 8% corresponded to premature births, with 1.2% born before 32 weeks or ‘extreme preterm’ [Citation16,Citation17]. In 2018, a total of 236,400 births were estimated in the country [Citation18]. Although birth rates have decreased in recent years, with an average of 1.77 children per woman (National Institute of Statistics, Chile, 2017) among the factors that have contributed to the increase in the number of premature babies is the increase in both maternal age and foreign pregnant women, who are also at risk mainly due to poor health conditions. The neonatal mortality rate per 1000 live births reached 5.2 in Chile (2018) and in 2016, 6.3% of the births corresponded to a weight less than 2,500 g (low birth weight).

According to the Department of Statistics and Health Information of the Chilean Ministry of Health, in 2016, a total of 8.2% of the births under 37 weeks of gestational age (GE) was reported (0.1% under 24 weeks, 0.3% between 24 and 27 weeks, 0.8% between 28 and 31 weeks, and 7% between 32 and 36 weeks). Regarding births in the country according to weight at birth, 6.3% of them corresponded to newborns with 2,999 g or less (1.1% less than 1,500 g and 5.2% between 1500 and 2,999 g). In a local experience, in the maternity ward of the Barros Luco Trudeau Hospital, a reference hospital of the public health system of the southern area of Santiago de Chile, 2.5% of the births weighing less than 1,500 g and 2.6% under 32 weeks of gestational age were reported in the period 2018–2019.

3.3. Colombia

3.3.1. Prematurity in Colombia

Currently, prematurity in Colombia is included in the indicators of low birth weight, which is considered a determinant of mortality and morbidity of newborns and a public health problem.

In 2016, the National Institute of Health INS published a research conducting a descriptive cross-sectional study, using the Vital Statistics database (DANE), identifying premature newborns for each of the years included in the analysis (https://www.dane.gov.co). Among 6,755,835 live birth registrations, 9.1% were preterm infants. The lowest percentage of premature infants was found in 2007 (8.49%) and the highest in 2016 (9.49%), documenting a sustained increase in the last years of the study. According to the characterization, 4.03% of preterm infants were extreme preterms, which corresponds to a rate of 3.66 per 1,000 live births; 10.46% were very preterm with a rate of 9.48 per 1,000 live births and 85.51% were moderate or late preterm with a rate of 71.11 per 1,000 live births.

In Colombia, for every 100 full-term live births, there are 10 preterm live births. It is estimated that between 12% and 20% of newborns are premature, which means around 80,000 premature babies on average per year. In 2018 of 637,669 neonates 76,520 were premature. The number of births in Colombia between January and March 2020 was 145,619, reflecting a reduction of 2.6% compared to the same period in 2019, when 149,528 were counted [Citation19].

3.3.2. Kangaroo Mother Program

The Kangaroo mother program was started in Colombia in 1979 with the philosophy of a change in the traditional management of the preterm and/or term low birth weight newborns, aiming an early discharge from the hospital to continue to be monitored as an outpatient basis. The country has been considered a pioneer in this program, and there is currently training of referents from more than 35 countries in several hospitals nationwide. Currently, there are 57 programs in operation in the country where premature infants are admitted when leaving the Neonatal Units with an approximate weight of 1700–1,800 g.

3.3.3. Extended immunization program in Colombia (PAI)

Colombia still does not have acellular vaccines in its schedule, but since 2017, the Colombian Association of Neonatology (ASCON) and the Colombian Society of Pediatrics (SCP) have been requesting and making pressure to the government for the introduction of aP in premature babies. In addition, vaccination has been promoted at 2 months regardless of weight or gestational age, starting at 6 weeks to encourage vaccination in the babies <1,800 grams who are still hospitalized.

In 2019, a consensus of experts was made among Neonatologists, Pediatricians, and Infectious Disease Specialists regarding the justification of hexavalent vaccine in prematures to be used in the Neonatal Units and Kangaroo Mother Programs throughout the country. Although the results are preliminary and the number of completed surveys is small, the preliminary results have allowed the Ministry of Health to consider the inclusion of hexacombined vaccines with aP for premature babies as a priority. Also, it has been achieved that the health paying entities authorize by formulation the application of these vaccines, especially in preterm babies hospitalized at 2 months of age.

It should be noted that in Colombia the adverse events after vaccination should be reported to the National Institute of Health; however, local and systemic events are not reported to this institution in many cases, and even worse, reports among premature infants are scarce. Documentation of apneas has been requested for this age group in particular.

After the start of the surveys and the initial meetings with the Ministry, the use of acellular vaccines in some neonatal units increased. The Colombian Association of Neonatology and the Ministry of Health began a pilot program carrying out the vaccination schedule at 2,4 and 6 months in a cohort of premature newborns weighing less than or equal to 2,000 g born on or after 1 July 2022, with acellular hexavalent vaccine, according to the national immunization schedule.

3.4. Mexico

In Mexico, every year more than 200,000 premature babies are born, and this condition is responsible for 28.8% of overall neonatal mortality. According to reports by the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, this group represents 9.75% of all births, which is higher than the average of 7.3% reported for Latin America [Citation20]. On the other hand, data provided by the National Institute of Perinatology find that with variations according to place of birth, these numbers range from 9% to 14% depending on the implicated risk factors. However, these numbers may be overestimated because this center only attends high-risk pregnancies [Citation20].

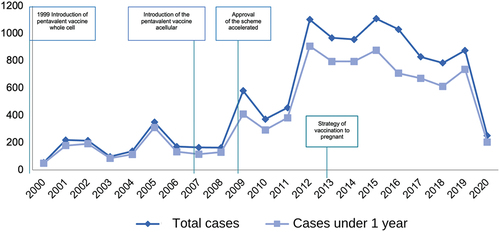

In Mexico, the massive application of whole-cell vaccine against diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus began in 1954. In 1999, the pentavalent vaccine against diphtheria, pertussis and tetanus with whole-cell vaccine, hepatitis B, and Haemophilus influenzae type b (DPT + HB + Hib) was accepted. Later, in 2007, it was replaced by the pentavalent vaccine containing the acellular pertussis component and an inactivated vaccine against poliomyelitis, with a schedule aimed mainly at infants and preschoolers with primary doses at 2, 4, 6 and 18 months and a booster with DPT vaccine at 4 years. In 2009, CONAVA temporarily approved the accelerated schedule with acellular pentavalent vaccine from 6 weeks, 3, 4 and 18 months as an early protection measure for children under 6 months [Citation21,Citation22], due in part to the epidemic outbreak that occurred in the northern States of the country from epidemiological week 48 of 2008 to week 22 of 2009. The special epidemiological surveillance subsystem of the Mexican Institute of Social Security (IMSS) reported that in the northern region, there were 79.8% of the cases notified in the country and of these 75% occurred in children under 1 year of age. In a 19-year study, the authors found a vaccination history of confirmed cases in a range of 27.3% to 61.5%, which highlights the decrease in vaccination coverage [Citation23].

In Mexico, pertussis among children under 1 year of age occurs in 13.1 per 100,000 inhabitants and up to 39.6 per 100,000 inhabitants depending on the year. Although it is a disease of mandatory and immediate notification in Mexico, there are no specific data on children with a history of prematurity, since these are included in the reports of children under 1 year of age [Citation24]. The Unified Information System for Epidemiological Surveillance (SUIVE) of the General Direction of Epidemiology in Mexico reported for the year 2020 a total of 251 cases of pertussis in the general population, with an incidence of 0.20 per 100,000 inhabitants and of these cases, 203 (81%) occurred in children under 1 year of age, mainly in winter months () [Citation25]. In the Epidemiological and Statistical System of Deaths in 2019, 46 deaths from vaccine-preventable diseases were reported, of which 31 (67%) occurred in children under 1 year of age [Citation22,Citation26,Citation27].

Figure 3. Reported cases of pertussis by year and those corresponding to children under one year of age in Mexico 2000–2020.

Own elaboration with data from Morbidity Yearbooks, General Direction of Epidemiology. Ministry of Health. Mexico [Citation25].

In 2010, Meza-Perez et al. reported the epidemiological aspects of pertussis in patients from the newborn period to preschool age from 2005 to 2008 at a reference hospital in Jalisco, Mexico [Citation28]. The prevalence for children under 2 months was 32.1%, transmission in general was 50–80%, and among household contacts from 30% to 87%; incomplete or absent vaccination schedule was documented in 93% of the cases. Complications occurred in 5% to 6% of the cases, among which the most important were pneumonia (22%), seizures (2%), encephalopathy (<5%), and the mortality rate was reported at 0.39 per 100 000 population.

In 2011, Gómez Rivera et al. reported 48 cases in children under 1 year of age with pertussis and pertussis-like syndrome that required hospitalization, out of a total of 250 cases treated at the Children’s Hospital of Sonora during 2009 and 2010. A 52% of cases corresponded to children aged 1–2 months and 35% to those aged 2–6 months; 73% lacked any dose of pertussis vaccine. In this series, mortality was 15%, which is 15 times higher than that reported by the WHO for the same period [Citation29].

Cruz-Romero et al., in 2013, conducted 56 surveys to caregivers of patients under 28 months and found that 85.3% had a complete vaccination schedule for their age, 30.3% received their vaccines with a delay from 1 to 11 months, and the vaccines with the greatest delay were the hepatitis B, influenza, and pneumococcal vaccine, highlighting the importance that for infants under 2 months and premature, delays in the application give them a significant risk [Citation30].

Arreola Ramírez et al. analyzed the vaccination status in premature infants under 1,500 g who were treated at the National Institute of Perinatology [Citation31]. This is the only Mexican report of vaccination status in premature babies and included 158 children with a history of prematurity captured in pediatric follow-up visits, with mean gestational age of 29.6 ± 2.4 and weight of 1135.8 ± 238.2 g, who remained hospitalized for 52.4 ± 28.3 days, whose weight at discharge varied between 1680 and 4800 g. Delays in vaccination were observed with a post-discharge time ranging from 5 to 151 days for the first dose of any indicated vaccine. In the case of the pentavalent acellular vaccine (DpaT, IPV, Hib), this was administered to 73.5% of the children in the study and the rest received the whole-cell pentavalent vaccine. These children received the first dose at the average age of 112.8 ± 41.2 days (3.7 months), the second dose at 181.5 ± 52.8 days (6 months), and the third dose at 259.4 ± 75 days (8.6 months); the causes of the delay in the administration of the vaccine were low weight and/or prematurity (30.4%), acute illness and/or hospitalization (11.4%), transfusion history (10.8%), and shortage (9.5%). For BCG vaccine, coverage rate was 98.1%, and 59.5% met completed rotavirus schedule, only 28% received three doses of pneumococcal vaccine, and for Hepatitis B, 95.5% received the vaccine alone or combined and 75.9% received three doses (). With this data, it was concluded that, on average premature babies of less than 1500 g receive their first vaccine with an average delay of 50 days after their hospital discharge, . Since most children are discharged with an average weight of 2000 g, it is suggested to vaccinate them before their discharge to avoid delays and be able to monitor them after the vaccine application, in case of adverse events, while other authors report that the delay in immunization of premature infants extends to 3 years of life [Citation32].

Table 2. Vaccination coverage in premature infants under 1500 g. (N = 158).

There has been a lag in compliance with the systematic universal vaccination schedule. It is reported that 30% of the children were not vaccinated because the service was stopped, 15% because appointments were rescheduled, and another 30% did not go to vaccination centers for fear of SARS-CoV2 contagion.

The WHO and UNICEF made a classification according to coverage data issued by the countries, in this Mexico occupies the fifth position with the greatest reduction in the rate of childhood vaccination. In addition to the problem of biological shortages reported in 2019 by PAHO, the Mexican Vaccination Observatory reported that in 2020, 3.5 million children did not receive the first dose of vaccine against diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus and as of 30 September 2021, 1,038,661 vaccines had not been applied.

By 2010, when pentavalent vaccine with acellular pertussis fraction was applied, according to the National Vaccination Coverage Survey (ENCOVA), the coverage of three doses of DPT vaccine in children under 2 years of age was 90.8%, but in the group of children under 1 year it was 70% and 60% in those of 2–4 months who are at higher risk of acquiring the disease and have complications or even death.

According to the National Health and Nutrition Survey (ENSANUT) 2018–19, it was estimated that 71% of the children in Mexico received at least three doses of acellular pentavalent vaccine according to the national vaccination schedule for that time. However, from 2012 to 2018, coverage for this vaccine in children under 5 years of age decreased by 18% points. The vaccination coverage in Mexico, considering those who accredited the doses applied with a national vaccination card or other official document for a scheme with four vaccines: BCG (one dose), Hepatitis B (three doses), acellular pentavalent (three doses) and Measles, rubella and mumps (one dose) [Citation33], which are significantly lower than estimated taking into account cases that do not present an official document, but the caregiver confirms its application, and no relationship is established with the type of vaccine applied.

Prematurity is an important health problem for Mexico and constitutes an indicator of the health conditions of a population. It reflects maternal health, timely access to health services, quality of care, and public policies on maternal and perinatal health and childcare programs. For this reason, it is necessary to establish strategies to prevent preterm delivery and maximize the quality of care for this vulnerable group and in this sense, one of the main strategies that should be promoted is timely vaccination and efficiency in coverage.

3.5. Costa Rica

In Costa Rica, pertussis was among the leading causes of vaccine-preventable deaths in the last decades, despite vaccine whole-cell pentavalent coverage rates close to 90% for the primary immunization schedule. However, vaccination data and coverage rates distributed by preterm or term infants have not been available.

A large pertussis outbreak that started in early 2006 was the worst in the country over the last 40 years and was associated with high morbidity and mortality rates [Citation34]. This led to a nationwide Tdap post-partum universal maternal vaccination, aiming to predominantly decrease hospitalizations and death. The results of this successful intervention have been previously reported [Citation34].

Since then, in 2012 the postpartum strategy was changed to maternal immunization with Tdap in the second or third trimester, and in every subsequent pregnancy. A combination and continuation of these strategies has maintained very low rates of pertussis admissions, and virtually no deaths have been reported in the last 3 years. However, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Tdap coverage rates for 2022 in pregnant women were only 67.6%. Pentavalent vaccine with IPV and acellular pertussis was introduced in 2010 and coverage increased, especially in the lowest development quintiles.

3.6. Panama

Since November 2014, the acellular hexavalent vaccine DTaP+Hib+HepB+ Inactivated polio was introduced and replaced the pentavalent vaccine. The current vaccination schedule for whooping cough includes acellular hexavalent vaccine at 2, 4, and 6 months (interval between doses 4–8 weeks); quadrivalent whole-cell TDP+Hib: 18 months (it can be given up to 47 months as a first booster, if the child does not arrive in a timely manner), TDP at 4 years which is considered as a second booster (from 2 1/2 to 3 years, after the first Tetravalent booster)

The plan for 2023 is to eliminate oral polio and the complete pertussis vaccine from our scheme by replacing the first booster at 18 months with acellular hexavalent and the second booster at 4 years with acellular tetravalent (DTaP+ inactivated polio).

In this country, reports of adverse events from acellular vaccines are available. Security data is reported to the Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI). These events are recorded by chronological age; however, gestational age for premature infants is not included. Reviewing the IAP data, it was evident that ESAVI reports have decreased since the start of the acellular vaccine. Since at these ages several concomitant vaccines are applied, it is uncertain to define exactly with which specific vaccine the effect is related.

According to the staff in charge of the National Immunization Program in Panama, the acellular vaccine has been very well accepted by family members and health personnel. For health workers, it means easier preparation and administration procedures and minimal risk of programmatic errors and needle costs. For family members, fewer reactions in their children have been described. Between 2010 and 2014 prior to inclusion of the acellular vaccine, an average coverage of has remained around 85%, and it has remained similar from after the inclusion of the acellular vaccine 2016 to 2018, with an average coverage of 85.1%. The year 2015 was excluded from the analysis due to vaccine shortages during that year, where coverage decreased to 70.9% [Citation35].

In Panama, epidemiological surveillance of pertussis was established in 1978 with an aggregated case collection system. In 2003, this system was changed to an individualized data collection system, allowing the capture of more epidemiological information. Since 1978: Weekly collective mandatory notification occurs.

The pertussis incidence rate decreased from a peak in 2006 of 4.0/100.00 inhabitants and then 1.3 in 2012 to a rate of 0.22 per 100,000 inhabitants in 2018 [Citation36]. From 2002, the Gorgas Memorial Institute of Health Studies (LCRSP-ICGES) introduced the conventional PCR methodology for the diagnosis of whooping cough and implemented at the same time the culture of Bordetella spp with different trainings over the years.

4. Discussion

Numerous studies conducted in recent decades have confirmed adequate immunogenicity and efficacy of the hexavalent vaccine in preterms, including those with very low birth weight, starting at 2 months of chronological age, and administered at similar doses than term babies and in newborns that are still hospitalized [Citation10]. Although the vaccine-induced antibody levels achieved in premature infants with the primary regimen are lower than those in full-term newborns, they reach adequate protective levels. There is a tendency to have a slight lower antibody response in low-birth-weight newborns for some of the pertussis components that increase with the booster dose at 18 months, emphasizing the importance of administration of this dose [Citation11].

The main adverse reaction after vaccination is apnea, usually occurring within 72 h of the hexavalent vaccine administration and with a peak in the initial 12–24 h. These reactions occur more commonly in premature babies with associated comorbidities associated to prematurity [Citation12]. The events described as apneas and/or low saturation rates recover spontaneously and are more common following the first vaccine dose. In the case of a cardiorespiratory event with the first dose, it is recommended to administer the second dose under a hospital setting in case of an emergency of life-threatening event [Citation13].

Premature and low birth at weight babies remain a high-risk group for developing severe acute respiratory disease due to pertussis, ending up in hospitalization, prolonged mechanical ventilation, or death. Therefore, delaying early immunizations in life has important implications, and this was one of the reasons for performing this analysis in selected Latin American countries. In an Italian study by Guarnieri et al. of pertussis hospitalizations [Citation37], preterm infants corresponded to 6.5% of these admissions, but of concern, delays in pertussis vaccinations in preterm infants occurred in 80%. In another study from England, Byrne et al. [Citation38] found that preterm infants have not benefited from the maternal pertussis immunization program to the same extent of full-term infants. Mothers of full-term infants were more often vaccinated than those premature, and of concern, preterms were more often admitted to the intensive care unit, had coinfections, and among pertussis fatalities, 38.5% were premature infants. Also, preterms had significantly longer hospitalizations than full-term babies, which probably indicates less protection due to shorter time periods of antibody transfer. More recently, in another study from England [Citation39,Citation40], extending the timing of maternal pertussis vaccination had positive effects in young preterm infants. Earlier vaccination during pregnancy led to a reduction of pertussis case hospitalizations.

Preterms are not only at greater risk of suffering from pertussis disease in early infancy compared with term infants [Citation41], but in the case of unvaccinated mothers against pertussis, may also be at higher risk of immunological interference or blunting [Citation40]. They may also be at a higher probability of suffering complications, including mechanical ventilation admission to PICU’s, and prolonged stays [Citation42]. Therefore, it is crucial to have quality of data among premature infants. In this review, we identified several gaps across the selected countries, despite recognizing the fact that these six countries have achieved significant major successes regarding vaccination against pertussis and other vaccine-preventable diseases. As shown, Argentina is the country with more robust and updated data. However, premature-focused data is lacking. On the other hand, Colombia has achieved successful numbers in terms of prematurity prevention, identification of high-risk groups to be immunized, and in implementing kangaroo programs. Overall, all six countries had useful basic pertussis information that is necessary to identify major obstacles, areas of improvement in terms of vaccination, surveillance, and disease prevention. However, information on areas of vaccine intervention for premature and low-birth weight infants was scarce.

We acknowledge the limitations of the study. First, the retrospective nature of our study and the lack of a standardized case collection form limited the amount of information we could retrieve at the end. Second, we focused our analysis in only six selected countries from Latin America which differ broadly in terms of millions of inhabitants, geographic distribution, and ethnic groups, among others. Third, many of the available publications did not distinguish between preterm and term babies nor babies who had low or normal birth weight. This failure was very common among the publications that we reviewed from different world regions. Fourth, we could not obtain information about breastfeeding in these infants due to the retrospective nature of the study. Certainly, this is a variable to analyze in similar but prospective studies, due to the well-known benefits to decrease chance of infections. Maternal Tdap vaccination induces high immunoglobulin levels in breast milk and these antibodies remain present through lactation period [Citation43]. Lastly, although there is robust evidence that the COVID-19 pandemic crisis has led to worsening of vaccine coverage rates in general, this study was retrospective, and therefore we could not focus in advance on pertussis vaccination rates among premature infants. On the other hand, the findings of this study highlight the importance of vaccination in premature infants and raises the concern about expanding the knowledge in this particular and vulnerable age group. In general, the administration of routine vaccinations during the first year of life in preterm infants is associated with protective antibody levels against most antigens [Citation44]; however, the response is lower in infants with very low birth weight or in extreme prematures. Encouraging vaccination of prematures with the available pentavalent and hexavalent acellular vaccines [Citation45,Citation46] should be a public health priority in Latin America and elsewhere, and the negative impact of delaying these immunizations should be a topic for discussion and education not only in antenatal care visits but also in maternities and health-care centers [Citation47].

5. Conclusion

With the decrease in vaccination coverage rates globally and in Latin America in particular, premature infants, who are a risk group, could be more affected. Countries should report vaccination coverage, breaking down premature infants as a separate group. It is known that the number of zero dose children has increased, Brazil is among the top 10 countries in the world with the largest number of children in this group. Similarly, other countries such as Mexico, Colombia, Venezuela, Haiti have increased the number of zero doses, which represents a risk for the entire region.

Premature and low birth weight infants should be a priority group for coverage and especially for catch-up campaigns, they should be included as a risk group apart from the rest of the child population.

Declaration of interests

M Avila-Agüero has received honorariums as a speaker from Sanofi for pertussis-related conferences, and economic support from Sanofi and the Global Pertussis Initiative (GPI) to attend pertussis-related meetings. C Mariño has received honorariums as a speaker from Sanofi for pertussis-related conferences and economic support from Sanofi and the Global Pertussis Initiative (GPI) to attend pertussis-related meetings. J Pablo Torres has received honorariums as a speaker from Sanofi for pertussis-related conferences and economic support from Sanofi and the Global Pertussis Initiative (GPI) to attend pertussis-related meetings. R Ulloa-Gutierrez has received honorariums as a speaker from Sanofi, GSK for pertussis-related conferences and economic support from Sanofi and the Global Pertussis Initiative (GPI) to attend pertussis-related meetings. A Gentile has received honorariums as a speaker from Sanofi for pertussis-related conferences and economic support from Sanofi to attend pertussis-related meetings. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or material discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contribution statement

All authors have made a significant contribution to the work reported; all have written and substantially revised the article; all have agreed on the journal to which the article will be submitted; all have reviewed and agreed on all versions of the article before submission, during revision, and the final version accepted for publication; all agree to take responsibility and be accountable for the contents of the article and to share responsibility to resolve any questions raised about the accuracy or integrity of the published work.

Acknowledgments

We thank Oscar Hidalgo, MD from the Instituto de Investigación en Ciencias Médicas (IICIMED) in San José, Costa Rica for his logistical contribution to organize the group, receive the material and organize the meetings for this manuscript.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Tan T, Dalby T, Forsyth K, et al. Pertussis across the globe: recent epidemiologic trends from 2000 to 2013. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2015;34(9):e222–32. doi: 10.1097/inf.0000000000000795

- Gentile Á, Torres-Torreti JP, López-López P, et al. Epidemiologic changes and novelties on vaccination against Bordetella pertussis in Latin America. Rev Chilena Infectol. 2021;38(2):232–242. English, Spanish. doi: 10.4067/s0716-10182021000200232

- Falleiros-Arlant LH, Torres JR, Lopez E, et al. Current regional consensus recommendations on infant vaccination of the Latin American pediatric infectious diseases society (SLIPE). Expert Rev Vaccines. 2020;19(6):491–498. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2020.1775078

- Hozbor D, Ulloa-Gutierrez R, Marino C, et al. Pertussis in Latin America: recent epidemiological data presented at the 2017 Global pertussis Initiative meeting. Vaccine. 2019;37(36):5414–5421. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.07.007

- Nunes A, Abreu A, Furtado B, et al. Epidemiology of pertussis among adolescents, adults, and older adults in selected countries of Latin American: a systematic review. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17(6):1733–1746. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2020.1827613

- Ulloa-Gutierrez R, Hozbor D, Avila-Aguero ML, et al. The global pertussis initiative: meeting report from the regional Latin America meeting, Costa Rica, 5-6 December, 2008. Hum Vaccin. 2010;6(11):876–880. PMID: 20980794. doi: 10.4161/hv.6.11.13077

- Gentile A, Bricks L, Ávila-Agüero ML, et al. Pertussis in Latin America and the Hispanic Caribbean: a systematic review. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2019;18(8):829–845. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2019.1643241

- Folaranmi T, Pinell-McNamara V, Griffith M, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of pertussis epidemiology in Latin America and the Caribbean: 1980-2015. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2017;41:e102. doi: 10.26633/rpsp.2017.102

- Falleiros Arlant LH, de Colsa A, Flores D, et al. Pertussis in Latin America: epidemiology and control strategies. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2014;12(10):1265–1275. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2014.948846

- Omeñaca F, Vázquez L, Garcia-Corbeira P, et al. Gómez IP, Liese J, Knuf M. Immunization of preterm infants with GSK’s hexavalent combined diphtheria-tetanus-acellular pertussis-hepatitis B-inactivated poliovirus-Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccine: a review of safety and immunogenicity. Vaccine. 2018;36(7):986–996.

- MINSAL. Instituto de Salud Pública, Ministerio de Salud de Chile. Informe Ejecutivo número 001 de fármacovigilancia en vacunas. Santiago: Instituto de Salud Pública, Ministerio de Salud de Chile, 10 de agosto de 2017. 2010. p. 10.

- Ministerio de Salud de Chile. Consejo Asesor de Vacunas e Inmunización. Postura del CAVEI ante la incorporación de la vacuna inactivada contra poliomielitis en el marco de la suspensión del uso de OPV y evaluación de inmunización del lactante con vacuna hexavalente. Santiago de Chile: Ministerio de Salud; 2018 de 10.

- Eventos adversos antes y después de la introducción de una vacuna DTaP-IPV-HBV-Hib (Hexaxim) al programa nacional de inmunizaciones en Chile”, Poster presentado en el Congreso Argentino de Pediatría, 2020.

- Aguirre-Boza F, San Martín PP, Valenzuela BM. How were DTP-related adverse events reduced after the introduction of an acellular pertussis vaccine in Chile? Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17(11):4225–4234. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1965424

- López Orellana P. Increase in preterm birth during demographic transition in Chile from 1991 to 2012. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:845968. doi: 10.1155/2015/845968

- Beck S, Wojdyla D, Say L, et al. The worldwide incidence of preterm birth: a systematic review of maternal mortality and morbidity. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88(1):31–38. doi: 10.2471/blt.08.062554

- Blencowe H, Cousens S, Chou D, et al. Born too soon: the global epidemiology of 15 million preterm births. Reprod Health. 2013;10(Suppl 1):SD: 1–14. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-10-s1-s2

- Indicadores básicos: Situación de Salud de las Américas. 2018. Organización Panamericana de la Salud (OPS) y Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS) para las Américas.

- https://fundacioncanguro.co/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Comportamiento-de-la-prematuridad-en-Colombia-durante-los-años-2007-a-2016.pdf

- Villanueva Egan LA, Contreras Gutiérrez AK, Pichardo Cuevas M, et al. Perfil epidemiológico del parto prematuro. Ginecol Obstet Mex. 2008;76(9):542–548. https://www.medigraphic.com/pdfs/ginobsmex/gom-2008/gom089h.pdf

- López-García B, Ávalos Antonio N, Díaz Gómez NB. Incidencia de prematuros en el Hospital General Naval de Alta Especialidad 2015-2017. Rev Sanid Milit Mex. 2018;72(1):19–23. https://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/rsm/v72n1/0301-696X-rsm-72-01-19.pdf

- Suárez-Iduela L, Herbas-Rocha I, Gómez-Altamirano CM, et al. Tos ferina, un problema vigente de salud pública en México. Planteamiento de la necesidad para introducir una nueva vacuna. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 2012;69(4):314–320. https://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/bmim/v69n4/v69n4a10.pdf

- Hernández PM, González SN. ¿Vacunar contra tos ferina? Rev Enfer Infec Pediatr. 28(107):428–432. 20014;27. https://www.medigraphic.com/pdfs/revenfinfped/eip-2014/eip141i.pdf

- Pérez-Pérez GF, Rojas-Mendoza T, Cabrera-Gaytán DA, et al. Panorama epidemiológico de la tosfrina: 19 años de estudio epidemiológico en el Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social. Rev Med Inst Mex Seguro Soc. 2015;53(2):164–170. https://www.medigraphic.com/pdfs/imss/im-2015/im152k.pdf

- Ojeda-González PC. Comparación del comportamiento epidemiológico de Tos ferina en menores de cinco años, de 1990-1997; 1999-2006 y 2008-2015 en México. Proyecto de titulación para obtener el grado de maestría en Salud Pública con área de concentración en enfermedades infecciosas. 2017.

- Graficas: Anuarios de morbilidad. Dirección General de Epidemiología. Secretaria de Salud, México. Accessed in: https://www.gob.mx/salud/acciones-y-programas/anuarios-de-morbilidad-1984-a-2020

- Dirección General de Epidemiología. Anuario de morbilidad 1984-2020. Consultado en. https://epidemiologia.salud.gob.mx/anuario/html/morbilidad_nacional.html

- Panorama Epidemiológico y estadístico de la mortalidad por causas sujetas a vigilancia epidemiológica en México 2019. Consultado en: https://www.gob.mx/salud/documentos/panorama-epidemiologico-y-estadistico-de-la-mortalidad-por-causas-sujetas-a-vigilancia-epidemiologica-en-mexico-2019

- Meza PA, Rodarte ER, Vázquez CJL. Panorama clínico-epidemiológico de tos ferina en un hospital de referencia. Pediatr Mex. 2010;12(1):6–10. https://www.medigraphic.com/pdfs/conapeme/pm-2010/pm101b.pdf

- Gómez-Rivera N, García-Zarate MG, Álvarez-Hernández G, et al. Tos ferina y síndrome coqueluchoide en niños menores de 1 año de edad: factores de riesgo asociada a mortalidad. Etsudio transversal descriptivo de 48 casos. Bol Clin Hosp Infant Edo Son. 2011;28(1):2–6. https://www.medigraphic.com/pdfs/bolclinhosinfson/bis-2011/bis111b.pdf

- Cruz-Romero EV, Pacheco-Ríos A. Causas de incumplimiento y retraso del esquema primario de vacunación en niños atendidos en el Hospital Infantil de México “Federico Gómez”. Aten Fam. 2013;20(1):6–11. https://www.elsevier.es/es-revista-atencion-familiar-223-pdf-S1405887116300785

- Langkamp DL, Hoshaw-Woodard S, Boye ME, et al. Delays in receipt of immunizations in low-birth-weight children: a nationally representative sample. Archives Of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2001;155(2):167–172. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.2.167

- ENSANUT. 2018-19. https://ensanut.insp.mx/encuestas/ensanut2018/doctos/informes/ensanut_2018_informe_final.pdf

- O’Ryan M, Calvo AE, Espinoza M, et al. Parent reported outcomes to measure satisfaction, acceptability, and daily life impact after vaccination with whole-cell and acellular pertussis vaccine in Chile. Vaccine. 2020;38(43):6704–6713. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.08.046

- Avila-Agüero ML, Camacho-Badilla K, Ulloa-Gutierrez R, et al. Epidemiology of pertussis in Costa Rica and the impact of vaccination: a 58-year experience (1961-2018). Vaccine. 2022 Jan 21;40(2):223–228. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.11.078

- Boletín estadístico 2018. Ministerio de Salud. Dirección General de Salud. Departamento de Epidemiología. Programa Ampliado de inmunizaciones. Panamá. 2018. https://www.minsa.gob.pa/sites/default/files/programas/boletin_2018.pdf

- Boletín epidemiológico #1.Ministerio de Salud-Dirección general de salud. Departamento de Epidemiología Panamá. Octubre 2019. https://www.minsa.gob.pa/sites/default/files/publicacion-general/boletin_3_hasta_se42-tos_ferina.pdf

- Guarnieri V, Giovannini M, Lodi L, et al. Severe pertussis disease in a paediatric population: the role of age, vaccination status and prematurity. Acta Paediatr. 2022;111(9):1781–1787. doi: 10.1111/apa.16436

- Byrne L, Campbell H, Andrews N, et al. Hospitalisation of preterm infants with pertussis in the context of a maternal vaccination programme in England. Arch Dis Child. 2018;103(3):224–229. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2016-311802

- Tessier E, Campbell H, Ribeiro S, et al. Impact of extending the timing of maternal pertussis vaccination on hospitalized infant pertussis in England, 2014-2018. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(9):e2502–e2508. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa836

- Abu-Raya B. Extending timing of immunization against pertussis during pregnancy and protection of premature infants from whooping cough disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(9):e2509–e2511. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa831

- Riise OR, Laake I, Vestrheim D, et al. Risk of pertussis in relation to degree of prematurity in children less than 2 years of age. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2017;36(5):e151–e156. doi: 10.1097/inf.0000000000001545

- van der Maas NAT, Sanders EAM, Versteegh FGA, et al. Pertussis hospitalizations among term and preterm infants: clinical course and vaccine effectiveness. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):919. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-4563-5

- Orije MRP, Larivière Y, Herzog SA, et al. Breast milk antibody levels in Tdap-vaccinated women after preterm delivery. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(6):e1305–e1313. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab260

- Rouers EDM, Bruijning-Verhagen PCJ, van Gageldonk PGM, et al. Association of routine infant vaccinations with antibody levels among preterm infants. JAMA. 2020;324(11):1068–1077. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12316

- Chiappini E, Petrolini C, Caffarelli C, et al. Hexavalent vaccines in preterm infants: an update by Italian society of pediatric allergy and immunology jointly with the Italian society of Neonatology. Ital J Pediatr. 2019;45(1):145. doi: 10.1186/s13052-019-0742-7

- Maertens K, Orije MRP, Huoi C, et al. Immunogenicity of a liquid hexavalent DTaP-IPV-HB-PRP∼T vaccine after primary and booster vaccination of term and preterm infants born to women vaccinated with Tdap during pregnancy. Vaccine. 2023;41(3):795–804. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.12.021