Abstract

Objective

To characterize the data on medications for lactating people in the LactMed database and evaluate the strength of the data for the most commonly administered medications in lactating women.

Methods

A retrospective analysis of all medications in the LactMed database in 12/2020 was performed. Each medication was classified into one of three categories: absent data, minimal-moderate data, strong data pertaining to safety in lactation. No data was defined as no available research studies associated with the medication. Minimal-moderate data was defined as absent research studies in one or more of the four LactMed categories: maternal drug levels, infant drug levels, effects on infants, effects on lactation, or if data was limited to a case report or observational study. Strong data was classified as availability of research studies in all four LactMed categories with data derived from pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic, cohort, case control, or randomized control studies. Additionally, the most commonly used medications in lactating women as defined by prior literature were analyzed for strength of data.

Results

1408 medications were evaluated: 714 (51%) had no associated data, 664 (47%) had minimal-moderate data, and 30 (2%) had strong data. Maternal drug level category had the highest proportion of rigorous supportive data while the effect on lactation category had the least supportive data. Of the most common mediations used in lactating women, sex hormones (contraception) and the nervous system medication classes had the most robust supportive data while respiratory, blood forming organs, and galactogogues had the weakest supportive data.

Conclusion

There is significant variability and dearth in the quality of data guiding recommendations for use of medications in lactation providing numerous opportunities for research.

Introduction

Breastfeeding has short and long term health benefits for parent and child. Approximately 83% of breastfeeding persons in the United States breastfeed at some point during the postpartum period [Citation1]. Postpartum women also face acute and chronic health problems that require medical management. According to the CDC Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), women of childbearing age have a 21.9% prevalence of depressive symptoms, 3.1% prevalence of diabetes, and 11% prevalence of hypertension [Citation2]. More than half of postpartum women require at least one medication [Citation3]. Women with medically complex pregnancies have more than 30% lower odds of exclusive breastfeeding as compared to women with uncomplicated pregnancies [Citation4]. Such discrepancy may stem from discouraging breastfeeding for women on medication due to lack of sufficient and reliable evidence regarding the medication’s effect on lactation [Citation5].

The National Library of Medicine and National Institutes of Health LactMed database is a comprehensive, publicly available online database (lact.nlm.nih.gov) commonly used by providers and the public. It includes information on the levels of the medication in breast milk and infant blood, the effect of the medication on breastfeeding, and the potential adverse effects of the medication on nursing infants. All data is derived from scientific literature, fully referenced, and updated monthly. LactMed is a comprehensive resource for lactating women, with an average of 15.1 references per medication, which is greater than other databases such as Lexicomp [Citation6]. Unfortunately, even LactMed often lacks the evidence necessary for health care providers to adequately counsel women on safety of medication use during breastfeeding [Citation7]. The aim of this study is to characterize the strength of data available for medications in the LactMed database and to evaluate the strength of data of the most commonly administered medications in lactating women.

Materials and methods

The LactMed database was reviewed for data associated with the most commonly administered medications for lactating women. The LactMed database was downloaded 12/2020, and the associated data for the drugs and chemicals was assessed between 12/2020 and 3/2021. LactMed sub-divides data for each medication into the following categories: drug levels – maternal, drug levels – infants, effects on breastfed infants, and effects on lactation and breastmilk. The breastfeeding recommendations for all medications in the LactMed database were analyzed for strength of data.

Medications were classified according to the World Health Organization (WHO) Anatomic Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system [Citation8]. If a drug belonged to multiple drug classes, the most common use delineated in the LactMed database was applied. For each medication, the data in the four categories in LactMed (maternal drug levels, infant drug levels, effects on infants, effects on lactation) was classified into one of three groups: absent data, minimal/moderate data, or strong data. Absent data was defined as no available research studies associated with the medication. Minimal-moderate data was defined as research studies that were limited to a case report or observational study. Strong data was defined as research studies with data derived from pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic, cohort, case control, or randomized control studies. Each medication was then assigned an overall classification score of absent, minimal/moderate, or strong data based on the strength of the sub-category data. The overall criteria for absent data was defined as no available data in any of the four sub-categories. The criteria for minimal/moderate data was defined as absent data in one or more of the four LactMed categories. Strong data was classified as availability of pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic, cohort, case control, or randomized control studies in all four LactMed categories. All medications were independently classified into one of the three categories by three authors (YF, JB, CYS). Discrepancies were resolved with joint discussion and review of literature.

Next, a modified list of the 103 most commonly prescribed medications during lactation was obtained from prior reviews on drugs in breastmilk [Citation9]. The category and overall classification classes for each of the most commonly used medications were reviewed and compared against the general LactMed database. Statistical analysis included Chi-Square and Fishers exact with p < 0.05 considered significant.

Results

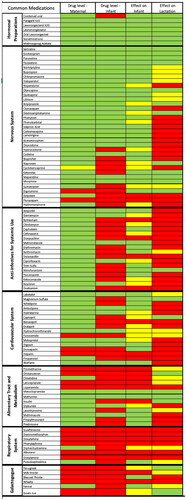

One-thousand four hundred and eight medications were analyzed. The most common medications were classified as the anti-infectives for systemic use (232, 16.5%), nervous system (228, 16.2%), and antineoplastic and immunomodulating agents (157, 11.2%) (). No associated data was available for 714 medications (51%), minimal-moderate data was available for 664 medications (47%), and strong data was available for 30 medications (2%) (). When evaluating the strength of data within each category, the maternal drug level had the highest proportion of strong data (417, 30%) while the effect on lactation had the lowest proportion of strong data (110, 8%) ().

Figure 1. (a) Percent of LactMed medications classified into absent, minimum/moderate, or strong categories based on strength of available data. (b) Classification of data that comprises each of the main four LactMed sub-groups into absent, minimum/moderate, or strong categories.

Table 1. ATC chemical classification system of LactMed medications.

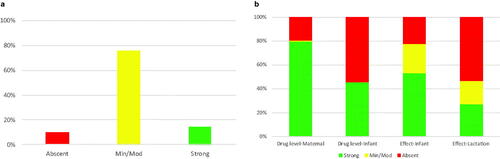

Evaluation of the most commonly used medications in lactation included the nervous system (n = 32), anti-infectives and anti-parasitics (n = 18), endocrine (n = 15), cardiovascular system (n = 12), alimentary tract/metabolism (n = 9), genitourinary system and sex hormones (n = 7), respiratory (n = 7), and various medications such as galactogogues (n = 6), gastrointestinal (n = 6), systemic hormonal preparation (n = 4), musculoskeletal system (n = 4), blood/blood forming organs (n = 3) (). Of the most commonly used medications during lactation, the strength of data varied across drug categories (p < 0.001, ). The strongest data was found for medications classified in the nervous system and genitourinary system/sex hormones drug classes. The weakest data was found in the respiratory system, blood and blood forming organs, and various galactogogue drug classes.

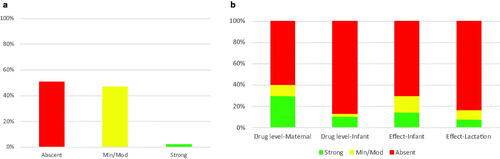

With regard to the most commonly used lactation medications, no associated data was available for 10 medications (10%), minimal-moderate data was available for 78 medications (75%), and strong data was available for 15 mediations (15%) (). When evaluating the strength of data within each category, the maternal drug level had the highest proportion of strong data (82, 80%) while the effect on lactation had the lowest proportion of strong data (28, 27%) (). The strength of data for each of the four LactMed categories for the most common 103 medications used in lactating women is depicted by a heatmap in .

Figure 2. (a) Percent of the most common medications classified into absent, minimum/moderate, or strong categories based on strength of available data. (b) Classification of data that comprises each of the main four LactMed sub-groups into absent, minimum/moderate, or strong categories amongst most commonly used medications.

Discussion

Only 2% of the medications in LactMed have recommendations that are supported by rigorous research in all four categories. Of the medications commonly used in the postpartum period, drug classes with the most rigorous data include are the genitourinary/sex hormones and the nervous system while the drug classes with the least amount of data include the respiratory system and galactagogues.

When comparing the overall LactMed data to the top 103 most common medications in the postpartum period, there was a statistically significant increase in the overall strength of data (2% vs 15%). The largest improvement in data strength was reported in the maternal drug level category (30% vs 80%). The smallest improvement in data strength was reported in the effect of medication on lactation category (8% vs 28%).

Our findings are in line with Mazer-Amirshahi et al. who reviewed labeling data of 213 new pharmaceuticals approved between January 2003 – December 2012, and concluded that 47.9% of the new medications had no associated data regarding breastfeeding, 42.7% had animal data only and 4.7% had human data [Citation10]. Our analysis of LactMed resulted in a similar conclusion, with approximately 51% of all medications having no associated data. The difference of 3% may be due to the inclusion of all therapeutic chemicals, not just FDA approved drugs, in our dataset.

Although our study identified contraception and antidepressants as classes of drugs with the strongest data, many consider the lactation research associated with these classes of medications to be limited. For example, in a Cochrane review of combined hormonal versus nonhormonal versus progestin-only contraception in lactation, the quality of evidence has been viewed as low-to-moderate quality due to the inconsistency of the results amongst trials [Citation11]. Similarly, a systematic review of data comparing the benefits and harms of anti-depressives in the postpartum period concluded that the evidence was largely inadequate to allow for informed decisions about treatment [Citation12].

Our study provides clinicians with data that systematically evaluates the strength of current literature presented in LactMed. These findings may further assist clinicians in counseling patients on medication use during lactation post-partum. Our study suggests that future research efforts should prioritize understanding of how medications effect lactation, with particular attention focused on respiratory system and galactagogues drug classes. We recognize that clinical lactation studies are costly, time consuming, and raise practical as well as ethical limitations [Citation7, Citation13]. Looking forward, attention can be directed toward non-clinical research methods such as in vitro (i.e. controlled environment such as petri dish), in vivo (i.e. within living organisms such as animal models), and physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models to fill the knowledge gap [Citation14]. In vitro cell culture models of mammary epithelium can predict medication partition into breast milk by both passive and active transport [Citation15]. In vivo studies use swine as a generally accepted model due to the anatomical and physiological similarities to human lactation [Citation16]. In silico techniques, such as physiologically based pharmacokinetic models (e.g. computer modeling) can be used to predict transfer of compounds into breastmilk. Mechanistic models (e.g. mode of action studies) have also been used to predict medication transfer into breastmilk [Citation17]. Lastly, although non-clinical research studies and PBPK models are important for bridging the knowledge gap, the value of human studies cannot be understated.

The strength of our study is the evaluation of all medications in the LactMed database with a sub-analysis for each of the four categories and the comprehensiveness of the evaluation. The limitations to this study include its cross-sectional nature, only evaluating the data at one distinct time point. Additionally, the National Library of Medicine and National Institutes of Health maintain the LactMed database, and although updated frequently, there may be a lag time between generation of new data and the update to the database. Additionally, we were not able to differentiate the quality of data for drug levels due to the nature of of a large database. Finally, other databases such as Lexicomp that may also contain lactation data were not included in this study.

The benefits of breastfeeding for both mothers and infants have been well documented and include reduced maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality; however, the paucity of data on medications’ effect on lactation limits a parent’s ability to breastfeed without concern for effects to the newborn. This study highlights the degree of variability in the rigor of data that comprises therapies used in lactating women and identifies areas for further research in specific sub-categories of commonly used drugs in lactation. Specifically, over-the-counter medications such as upper respiratory medications (respiratory category) and galactagogues (various category) are among the commonly used medications with most limited available data. Improved understanding of how medicine effects breastfeeding will have a positive impact on postpartum care.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Healthy People 2020 [Internet]. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. 2021. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/data-search/Search-the-Data#objid=4859

- Robbins C, Boulet SL, Morgan I, et al. Disparities in preconception health Indicators – Behavioral risk factor surveillance system, 2013-2015, and pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system, 2013-2014. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2018;67(1):1–16.

- Saha MR, Ryan K, Amir LH. Postpartum women’s use of medicines and breastfeeding practices: a systematic review. Int Breastfeed J. 2015;10:28.

- Kozhimannil KB, Jou J, Attanasio LB, et al. Medically complex pregnancies and early breastfeeding behaviors: a retrospective analysis. PloS One. 2014;9(8):e104820.

- Hussainy SY, Dermele N. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of health professionals and women towards medication use in breastfeeding: a review. Int Breastfeed J. 2011;6:11.

- Holmes AP, Harris JB, Ware S. Evaluation of lactation compatibility reference recommendations. Ann Pharmacother. 2019;53(9):899–904.

- Byrne JJ, Spong CY. Is it safe?” – the many unanswered questions about medications and Breast-Feeding. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(14):1296–1297.

- Guidelines for ATC classification and DDD assignment. WHO collaborating centre for drug statistics methodology. 2020. https://web.archive.org/web/20150806013259/http:/www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_publications/guidelines/

- Newton ER, Hale TW. Drugs in breast milk. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2015;58(4):868–884.

- Mazer-Amirshahi M, Samiee-Zafarghandy S, Gray G, et al. Trends in pregnancy abelling and data quality for US-approved pharmaceuticals. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211(6):690 e1–11–690.e11.

- Lopez LM, Grey TW, Stuebe AM, et al. Combined hormonal versus nonhormonal versus progestin-only contraception in lactation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;3: CD003988.

- McDonagh MS, Matthews A, Phillipi C, et al. Depression drug treatment outcomes in pregnancy and the postpartum period: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(3):526–534.

- Weld ED, Bailey TC, Waitt C. Ethical issues in therapeutic use and research in pregnant and breastfeeding women. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2022;88(1):7–21.

- Nauwelaerts N, Deferm N, Smits A, et al. A comprehensive review on non-clinical methods to study transfer of medication into breast milk – A contribution from the ConcePTION project. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021;136:111038.

- Kimura S, Morimoto K, Okamoto H, et al. Development of a human mammary epithelial cell culture model for evaluation of drug transfer into milk. Arch Pharm Res. 2006;29(5):424–429.

- Roura E, Koopmans SJ, Lallès JP, et al. Critical review evaluating the pig as a model for human nutritional physiology, Nutr Res Rev. 2016;29:60–90.

- Corley RA, Mast TJ, Carney EW, et al. Evaluation of physiologically based models of pregnancy and lactation for their application in children’s health risk assessments. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2003;33(2):137–211.