Abstract

Objective

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of maternal deaths in high-income countries. This study aimed to assess the characteristics of maternal deaths due to CVDs and the quality of care provided to patients, and to identify elements to improve maternal care in Japan.

Methods

This descriptive study used the maternal death registration data of the Maternal Deaths Exploratory Committee of Japan between 2010 and 2019.

Results

Of 445 eligible pregnancy-related maternal deaths, 44 (9.9%) were attributed to CVD. The most frequent cause was aortic dissection (18 patients, 40.9%), followed by peripartum cardiomyopathy (8 patients, 18.2%), and pulmonary hypertension (5 patients, 11.4%). In 31.8% of cases, cardiopulmonary arrest occurred within 30 min after initial symptoms. Frequent symptoms included pain (27.3%) and respiratory symptoms (27.3%), with 61.4% having initial symptoms during the prenatal period. 63.6% of the patients had known risk factors, with age ≥35 years (38.6%), hypertensive disorder (15.9%), and obesity (15.9%) being the most common. Quality of care was assessed as suboptimal in 16 (36.4%) patients. Cardiac risk assessment was insufficient in three patients with preexisting cardiac disease, while 13 patients had symptoms and risk factors warranting intensive monitoring and evaluation.

Conclusion

Aortic dissection was the leading cause of maternal death due to CVDs. Obstetrics care providers need to be familiar with cardiac risk factors and clinical warning signs that may lead to impending fatal cardiac events. Timely risk assessment, patient awareness, and a multidisciplinary team approach are key to improving maternal care in Japan.

Introduction

As more women give birth later in life and as non-communicable diseases become more prevalent in high-income countries, maternal deaths due to cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are steadily increasing. In the United States, CVD is the major cause of maternal death, accounting for >25% of pregnancy-related mortalities [Citation1]. In the United Kingdom, CVD is the leading cause of indirect maternal death and overall death, with a rate of 2.31 per 100,000 pregnancies [Citation2].

CVDs potentially resulting in maternal death include coronary artery disease, peripartum cardiomyopathy, aortic dissection, arrhythmia, valve disease, congenital heart disease, pulmonary hypertension (PH), and myocarditis. The mortality rate for aortic dissection and PH in pregnancy is higher than for other CVDs, at 50% for aortic dissection in Japan [Citation3] and between 30 and 56% for PH globally [Citation4]. For coronary artery diseases, mortality rates of 9% for myocardial infarction and 4% for spontaneous coronary artery dissection during pregnancy have been reported [Citation5,Citation6]. Globally, peripartum cardiomyopathy accounts for 9% of maternal mortality [Citation7], while severe mitral valve stenosis and aortic valve stenosis are associated with mortality rates of 3% and 2%, respectively [Citation8].

In Japan, where 99.9% of about 1,000,000 annual births occur at facilities, approximately half of these occur at local clinics with one or two full-time obstetricians, and the other half occur at hospitals having more full-time obstetricians [Citation9]. Japan has seen an increase in pregnant women over the age of 35 (28.1% in 2015), as well as a trend in first births among older women (mean of 30.7 years old in 2015) [Citation10]. Between 2010 and 2017, 45 maternal deaths, on average, occurred annually [Citation11]. Tanaka [Citation12] reported an increasing trend in maternal death due to CVD in 2010–2011 in Japan. As maternal death due to CVD has become a major public health issue, further understanding of pregnancies complicated with CVD in Japan is warranted. Therefore, we aimed to assess clinical characteristics in each maternal death attributed to CVD in Japan. We also assessed the quality of obstetric care provided to each patient to address strategies to alleviate such maternal deaths.

Materials and methods

In this observational study, maternal death registration data between 2010 and 2019 from the Maternal Deaths Exploratory Committee in Japan was used. The committee was started in 2010 by The Japan Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists as a nation-wide registration system to collect and review detailed information on deaths during pregnancy or during the year following pregnancy in Japan. The committee members, including 15 obstetricians and other relevant specialists, assess and prepare a causal analysis report on each case to report on the most attributable causes of death, preventability, and concerns related to the clinical care provided to patients [Citation11,Citation13,Citation14]. The preventability decision was made by a majority vote [Citation14]. For direct and indirect maternal deaths, the committee used the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision (ICD-10) definition [Citation15]: deaths with a direct causal link to pregnancy status and deaths for which pregnancy status is unrelated to the cause of death, respectively. Late maternal death was categorized separately and defined as the death of a woman >42 days but <1 year after the termination of a pregnancy [Citation15]. This system assessed the same maternal deaths as the number reported in the vital statistics published by Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare in Japan, as health institutions are recommended to report maternal deaths to the committee [Citation11].

In this report, we analyzed the summarized overall results of each maternal death case, which the committee concluded. We extracted maternal death cases attributed to the following CVDs: (i) coronary artery disease (ischemic heart disease), (ii) peripartum cardiomyopathy, (iii) aortic dissection, (iv) arrhythmia, (v) valve disease (cardiac valvular disease), (vi) congenital heart diseases, (vii) PH, (viii) myocarditis, and (ix) others [Citation1,Citation16]. Patients who died of accidental causes were excluded from the analysis.

First, the causes of death and the characteristics of the patients with CVD were analyzed as follows: the incidence of maternal death due to CVD, the number of cases with each type of CVD, types of maternal death (direct/indirect), patient age, parity, the occurrence of the first symptom (prenatal, during labor, postpartum), and length of time between the occurrence of the first symptom and cardiopulmonary arrest (CPA). Through this process, we extracted data from the overall results that the committee reported on the occurrence of the first symptom, which reflects the time at which the patients’ reported their symptoms for the first time based on the retrospective medical chart review by facilities at which the death occurred. We also assessed each case for initial symptoms and cardiac risk conditions, including physical risk factors and existing cardiac disease. We used the risk factors listed in the 8th Report of the Confidential Inquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom [Citation2] and the 2019 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists guidelines [Citation17], including age (≥35 years), hypertension, and obesity, along with all relevant medical histories of patients and family members. In this study, we considered hypertension to include all conditions defined as hypertensive disorders of pregnancy [Citation18], and we defined obesity as a recorded body mass index (BMI) of >30 at death. We also compared each CVD in terms of these characteristics.

Second, for cases categorized as preventable by the committee, we performed additional analysis on what elements in each clinical course contributed to the decision and identified opportunities for improvement in care quality. We focused on three conditions: (i) in cases with preexisting cardiac disease, whether the cardiac disease was appropriately assessed before or during early pregnancy, in line with the standard assessment described in the modified World Health Organization (mWHO) classification [Citation19]; (ii) in cases where CVD developed or exacerbated during pregnancy or postpartum, whether sufficient pre-diagnostic assessment and examination of emerging symptoms or risk factors had been provided; and (iii) in all cases where CVD either preexisted or developed during pregnancy or the postpartum period, whether optimal post-diagnostic management was provided through multidisciplinary measures and/or intensive care.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committees of the National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center of Japan (receipt number N18-34) and the Japan Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Results

Characteristics of maternal deaths due to CVDs

Between 2010 and 2019, the committee evaluated 452 maternal deaths. Seven deaths due to accidental causes were excluded; 445 cases were included in the analysis. Forty-four patients (9.9%) concluded CVDs as a cause of death by the committee were eligible for this analysis. The characteristics of 44 cardiovascular cases are summarized in .

Table 1. Characteristics of maternal deaths due to cardiac disease (n = 44).

The most frequent cause was aortic dissection (n = 18, 40.9%), followed by peripartum cardiomyopathy (n = 8, 18.2%). Only nine cases (eight peripartum cardiomyopathy cases and one arrythmia case) were classified as direct maternal deaths. The remaining deaths comprised 34 indirect maternal deaths and one late maternal death. CVD ranked the highest as the cause of indirect maternal death, comprising approximately one-third (31.5%) of all indirect maternal deaths.

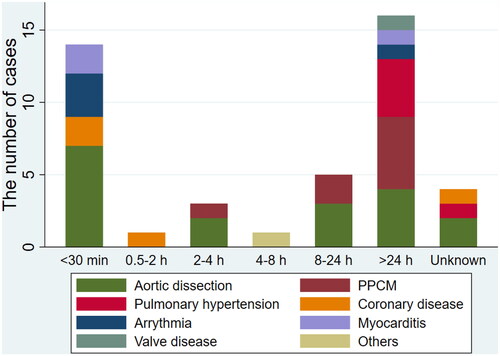

In 54.5% (n = 24) of patients, CPA occurred within 24 h of the first symptom (). Of these, 14 (31.8%) patients had a more severe course, with a CPA occurring within 30 min. Sixteen (36.4%) patients had a CPA >24 h after the first clinical signs, ranging from one to 114 days.

Figure 1. The length of time between the occurrence of the first symptom and CPA according to diagnosis. PPCM: peripartum cardiomyopathy; CPA: cardiopulmonary arrest.

The CVD characteristics are described in . Twenty-seven (61.4%) patients had their first symptoms during pregnancy, of which the most common trimester was the third trimester (n = 16, 36.4%). Patients with aortic dissection and PH developed the first symptom mainly during the prenatal period, while all patients with cardiomyopathy developed it during the postpartum period, except for two patients in whom it occurred in the third trimester.

Table 2. Disease-specific characteristics of maternal deaths due to cardiac disease.

Regarding initial symptoms, pain or respiratory symptoms (e.g. dyspnea and cough) were reported in 54.6% (n = 24) of patients. Pain, mainly chest and back pain, was the most frequent among patients with aortic dissection. Three-quarters of the peripartum cardiomyopathy patients presented with respiratory symptoms.

Multiple risk factors were common among maternal deaths due to cardiac causes, although 16 (36.4%) patients had no known risk factor. The most common risk factor was age, with one-third of the patients being ≥35 years old. Three out of 18 patients with aortic dissection had CVD-related histories, including pre-diagnosed connective tissue disorder, preexisting arteritis, and a family history of sudden death. For peripartum cardiomyopathy cases, five of eight patients had hypertension. All deaths involving twin pregnancies were due to cardiomyopathy. There were no cases complicated by cardiac disease classified as either mWHO class IV or V.

Quality of care assessment and preventability

Overall, 28 maternal deaths occurred either under optimal care or with the unexpected, sudden development of severe cardiac condition. Therefore, the committee considers these deaths difficult to prevent. We analyzed the remaining 16 cases categorized as suboptimal in the quality of care. Specific patient care was provided during the following periods: (i) pre-pregnancy period (n = 3); (ii) pre-diagnostic period (n = 10); and (iii) post-diagnostic period (n = 3).

Possible cardiac risk assessment before or during early pregnancy

Among six cases with preexisting cardiac conditions, three patients showed insufficient preliminary cardiac risk assessment. In one case, cardiac risk assessment during early pregnancy could have been performed if there was good communication between the physician who followed the patient for her cardiac disease and her primary obstetrician. In another case, a patient presented with progressively worsening cardiac condition while undergoing assisted reproductive technology. Referral and communication between a cardiologist and fertility physicians assisting with reproduction were warranted. In yet another case, the patient’s CVD-related diagnosis was not shared with the care providers.

Pre-diagnostic assessment/examination

Among the 44 cases in which CVD developed or exacerbated during pregnancy or postpartum, ten cases with emerging cardiac symptoms and risk factors may have benefited from prompt examinations and resuscitation. One case was attributed to a patient education factor: a lack of patient awareness regarding dyspnea. The remaining cases were attributed to provider factors, including delays in recognizing heart failure symptoms (dyspnea and edema) (n = 2) and providing advanced examinations and management, including contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) for persistent or unexplained pain and transthoracic echocardiography for unexplained respiratory symptoms or symptoms of circulatory failure (n = 6). For the remaining case with electrolyte abnormalities, the reason for suboptimal care assessment was insufficient monitoring for possible adverse cardiac events.

Post-diagnostic management

Among the 44 cases in which CVD either preexisted or developed during pregnancy or the postpartum period, well-coordinated multidisciplinary/intensive management was insufficient after the diagnosis of CVD in three cases. In one case, a diagnosis of CVD, which could have led to a sudden cardiac arrest, was not shared on time among care providers. As a result, possible contraindicated medicine could not be avoided. Another case developed severe cardiac failure at term. The best mode of delivery for the cardiac condition and the importance of intensive hemodynamic management should have been better discussed among a multidisciplinary team. The last case experienced sudden onset of a critical CVD condition. Although a more advanced medical unit would have been a better option considering the severity of the disease and the possibility of a worse clinical course, it was not provided.

Discussion

This study identified important aspects of maternal deaths due to CVDs in Japan. First, CVD was a major cause of indirect maternal deaths in Japan (31.5%), with aortic dissection being the leading cause. In many high-income countries, CVD is the largest individual cause of maternal death [Citation1,Citation2,Citation16,Citation20]. Aortic dissection is one of the major causes of maternal death due to CVD in several European countries [Citation2,Citation16,Citation20]. In contrast, some countries showed more frequent incidences of maternal death due to cardiomyopathy, ischemic heart disease, and arrhythmia [Citation16,Citation20,Citation21].

Second, chest or back pain and dyspnea are frequent initial symptoms among maternal deaths due to CVDs. Patients with chest or back pain should be examined for aortic dissection, especially if the pain is persistent or severe. Obstetric care providers should not hesitate to perform CECT, if necessary [Citation17]. Similarly, dyspnea, palpitations, and edema are key symptoms that may indicate a cardiac condition. These symptoms can mimic conditions that frequently reflect hemodynamic changes in the second half of pregnancy in healthy pregnant women [Citation17,Citation22]. In 2018 and 2019, the committee recommended clinicians suspect CVD if pregnant women presented with persistent or severe respiratory symptoms and to examine for aortic dissection if a patient complained of severe pain around the chest or back [Citation23,Citation24]. A similar recommendation has been published in several countries, highlighting the importance of discerning varied cardiac conditions [Citation16,Citation25].

Third, age ≥35 years (38.6%), hypertensive disorder (15.9%), and obesity (15.9%) were the most common risk factors among patients who died due to CVDs. The percentage of maternal deaths due to CVD in Japan in patients aged ≥35 years was similar to that in other high-income countries [Citation20,Citation25]. However, the percentage of patients with obesity was much less than that seen in the Nordic countries (27%) [Citation20], the USA (37.5%) [Citation25], and the UK (60%) [Citation2]. Further research is warranted to investigate other putative factors that could explain why CVD is the major cause of maternal death in Japan since we observed a lower rate of obesity in this cohort. Considering that aortic dissection has several risk factors other than those related to lifestyle [Citation26], ethnicity and genetic variations may contribute to a higher frequency of aortic dissection in Japanese population.

Finally, avoidable factors were identified in one-third of patients in relation to various clinical events that resulted in maternal death. CVDs can preexist or develop during pregnancy. Pregnant women with known heart disease should be evaluated for their cardiac status and undergo risk assessment [Citation27]. They also benefit the most through timely counseling, from preconception to early pregnancy, by an obstetrician, which focuses on educating them about the disease and its risks during pregnancy. Some patients develop adverse maternal conditions, such as preeclampsia, during pregnancy and postpartum, which can pose an additional risk to existing CVD or trigger the development of acute cardiac diseases. Repeated risk assessment and timely referral to a multidisciplinary team headed by cardiac and obstetric specialists are key to improving care and ultimately saving mothers [Citation28]. Also, every checkup visit is an important opportunity for raising patient awareness. Their primary obstetricians should focus on checking warning signs as well as educating patients about critical symptoms.

This study had some limitations. First, the committee categorized maternal causes of death based on registered reports; however, the classification may have been erroneous due to limited data in the reports. Second, cardiac symptoms may manifest as benign pregnancy-related symptoms, which has been reported as a reason for the delay in recognition of disease onset from both patient and provider perspectives [Citation25]. In this instance, the time from the first symptom to CPA may have been underestimated. Third, we used BMI at death as a proxy measure of the BMI status of our population in this report. Using BMI at death could result in an overestimation of obesity in our population. Lastly, we were unable to include social-economic components such as insurance and education status as possible contributors to maternal deaths due to CVDs [Citation29].

In conclusion, CVD represented as aortic dissection substantially affected maternal mortality in Japan. Building a universal system that encompasses three critical care points, namely, early risk assessment, patient awareness, and a multidisciplinary team approach, is likely to improve maternal care in Japan. From preconception to the postpartum period, a continuum of care that involves patient education and interdisciplinary cooperation can help identify and prevent a series of clinical events that may otherwise result in maternal death.

Author contributions

TM, AT, and SA conceptualized, designed, and conducted the study. TA, AS, JH, HT, SK, MN, TM, TI, and II collected data and contributed to the analysis of each maternal death due to CVD. TM, AT, and SA drafted the study result, and JH, HT, SK, MN, TM, TI, and II contributed to critically reviewing and revising the content. All authors are responsible for the integrity of the study and accuracy of the work during the analysis.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all members of the committee for their dedication and work in reviewing maternal deaths.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Knypinski J, Wolfe DS. Maternal Mortality due to cardiac disease in pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2020;63(4):799–807.

- Cantwell R, Clutton-Brock T, Cooper G, et al. Saving Mothers’ lives: reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer: 2006-2008. The eighth report of the confidential enquiries into maternal deaths in the United Kingdom. Bjog. 2011;118(Suppl 1):1–203.

- Tanaka H, Kamiya CA, Horiuchi C, et al. Aortic dissection during pregnancy and puerperium: a japanese nationwide survey. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2021;47(4):1265–1271.

- Weiss BM, Zemp L, Seifert B, et al. Outcome of pulmonary vascular disease in pregnancy: a systematic overview from 1978 through 1996. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31(7):1650–1657.

- Elkayam U, Jalnapurkar S, Barakkat MN, et al. Pregnancy-associated acute myocardial infarction: a review of contemporary experience in 150 cases between 2006 and 2011. Circulation. 2014;129(16):1695–1702.

- Havakuk O, Goland S, Mehra A, et al. Pregnancy and the risk of spontaneous coronary artery dissection: an analysis of 120 contemporary cases. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10(3):e004941.

- Kerpen K, Koutrolou-Sotiropoulou P, Zhu C, et al. Disparities in death rates in women with peripartum cardiomyopathy between advanced and developing countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2019;112(3):187–198.

- Ducas RA, Javier DA, D'Souza R, et al. Pregnancy outcomes in women with significant valve disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart. 2020;106(7):512–519.

- Ministry of Health. Labour and welfare of Japan. Survey of Medical Institutions 2014. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/iryosd/14/

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan. The final count of the vital statistics 2015. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/jinkou/kakutei15/

- Hasegawa J, Katsuragi S, Tanaka H, et al. Decline in maternal death due to obstetric haemorrhage between 2010 and 2017 in Japan. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):11026.

- Tanaka H, Katsuragi S, Osato K, et al. The increase in the rate of maternal deaths related to cardiovascular disease in Japan from 1991-1992 to 2010-2012. J Cardiol. 2017;69(1):74–78.

- Katsuragi S, Tanaka H, Hasegawa J, Maternal Death Exploratory Committee in Japan and Japan Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, et al. Perinatal outcome in case of maternal death for cerebrovascular acute disorders: a nationwide study in Japan. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022;35(13):2429–2434.

- Hasegawa J, Sekizawa A, Tanaka H, Japan Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, et al. Current status of pregnancy-related maternal mortality in Japan: a report from the maternal death exploratory committee in Japan. BMJ Open. 2016;6(3):e010304.

- World Health Organization. The WHO application of ICD-10 to deaths during pregnancy, childbirth and puerperium: ICD-MM. Geneva: world Health Organization 2012. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/70929/9789241548458_eng.pdf;jsessionid=760373AA8A881D03E12D07772DA4EF42?sequence=1

- Lameijer H, Schutte JM, Schuitemaker NWE, Dutch Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Committee, et al. Maternal mortality due to cardiovascular disease in The Netherlands: a 21-year experience. Neth Heart J. 2020;28(1):27–36.

- ACOG Practice Bulletin No 212: pregnancy and heart disease. Obstetri Gynecol. 2019;133(5):e320–e356.

- Brown MA, Magee LA, Kenny LC, International Society for the Study of Hypertension in Pregnancy (ISSHP), et al. Hypertensive Disorders of pregnancy: ISSHP classification, diagnosis, and management recommendations for international practice. Hypertension. 2018;72(1):24–43.

- Pijuan-Domenech A, Galian L, Goya M, et al. Cardiac complications during pregnancy are better predicted with the modified WHO risk score. Int J Cardiol. 2015;195:149–154.

- Nyflot LT, Johansen M, Mulic-Lutvica A, et al. The impact of cardiovascular diseases on maternal deaths in the nordic countries. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021; Jul100(7):1273–1279.

- Lima FV, Yang J, Xu J, et al. National Trends and in-Hospital outcomes in pregnant women with heart disease in the United States. Am J Cardiol. 2017 May 15;119(10):1694–1700.

- Sherman-Brown A, Hameed AB. Cardiovascular Disease screening in pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2020;63(4):808–814.

- The Japan Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (JAOG) and the Japan Maternal Death Exploratory Committee (JMDEC). Recommendations for saving mother. (Vol. 9). Tokyo: JAOG and JMDEC; 2018.

- The Japan Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (JAOG) and the Japan Maternal Death Exploratory Committee (JMDEC). Recommendations for saving mother. (Vol. 10). Tokyo: JAOG and JMDEC; 2019.

- Hameed AB, Lawton ES, McCain CL, et al. Pregnancy-related cardiovascular deaths in California: beyond peripartum cardiomyopathy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(3):379 e1–379.e10.

- Sen I, Erben YM, Franco-Mesa C, et al. Epidemiology of aortic dissection. Semin Vasc Surg. 2021;34(1):10–17.

- Regitz-Zagrosek V, Roos-Hesselink JW, Bauersachs J, ESC Scientific Document Group, et al. 2018 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(34):3165–3241.

- Sharma G, Zakaria S, Michos ED, et al. Improving Cardiovascular workforce competencies in Cardio-Obstetrics: current challenges and future directions. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(12):e015569.

- Kramer MR, Strahan AE, Preslar J, et al. Changing the conversation: applying a health equity framework to maternal mortality reviews. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221(6):609.e1–609.e9.