Abstract

Objective

To examine the association between unknown maternal Group B Streptococcal (GBS) colonization and the risk of severe neonatal morbidity among individuals undergoing planned cesarean delivery.

Methods

We performed a secondary analysis of a multicenter, prospective observational study of individuals with singleton gestations and planned cesarean delivery ≥37 weeks gestation with cervical dilation ≤3 cm, intact membranes, and no evidence of labor or induction. GBS status was categorized as positive, negative, or unknown. The primary outcome was a composite of severe neonatal morbidity, including clinical or culture-proven sepsis, ventilator support in the first 24 h, respiratory distress syndrome, hypotension requiring treatment, intubation, necrotizing enterocolitis, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, or death. We compared individuals with unknown GBS status to those with positive and negative GBS status.

Results

In this cohort, 4,963 individuals met inclusion criteria; 72% had unknown GBS status, 25% were GBS negative and 3% were GBS positive. Among individuals with unknown GBS status, 208 (5.9%) had the primary composite neonatal outcome, compared with 75 (6%) of GBS negative individuals and 6 (4%) of GBS positive individuals. There was no difference in composite severe neonatal morbidity among GBS unknown, GBS negative, and GBS positive individuals (5.9% vs 6% vs 4%, p = .61). After adjusting for male sex and intrapartum antibiotic exposure, unknown GBS status was not associated with severe neonatal morbidity (adjusted risk ratio, 0.95; 95% confidence interval, 0.73–1.22).

Conclusion

GBS status at time of planned cesarean delivery does not appear to be associated with composite severe neonatal morbidity. The cost effectiveness and clinical utility of GBS screening among individuals undergoing planned cesarean delivery requires further investigation.

Introduction

Approximately 1 in 4 pregnant individuals are carriers of Group B Streptococcus (GBS). Maternal risk factors for GBS colonization include obesity, Black race, and working as a health care professional [Citation1,Citation2]. GBS is the leading cause of neonatal infection; each year 900 infants are diagnosed with early-onset GBS disease and 1,200 with late-onset GBS disease [Citation3]. Early-onset neonatal GBS disease can result in severe neonatal morbidity including sepsis, meningitis, pneumonia, and neonatal death [Citation4]. Cesarean delivery decreases the risk of neonatal GBS transmission among individuals who are GBS colonized [Citation5–7]. However, cesarean delivery does not eliminate the risk of neonatal transmission because GBS can cross intact membranes, [Citation8]. Intrapartum antimicrobial prophylaxis decreases the risk of early-onset neonatal GBS disease [Citation9–11]. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends routine GBS screening for all pregnant individuals, including those undergoing a planned cesarean section, due to the risk of labor and/or ruptured membranes prior to delivery [Citation8]. Despite this recommendation, some clinicians may opt to forego screening in individuals undergoing planned cesarean delivery who are unlikely to labor.

Neonatal risks associated with maternal GBS colonization in individuals undergoing planned cesarean delivery are not well known. The CDC endorses that the risk for early-onset GBS disease among full-term infants delivered via cesarean delivery prior to onset of labor and with intact amniotic membranes is low [Citation8]. This report is based on data from a single-center retrospective study in the U.S. [Citation12], a national population-based study from Sweden [Citation6], and a review of CDC active, population-based surveillance data (CDC, unpublished data, 1998–1999 and 2003–2004). While these data describe neonatal colonization rates, they do not define planned (or elective) cesarean delivery nor address specific neonatal morbidities. Furthermore, universal GBS screening among individuals planning a repeat elective cesarean may not be cost-effective in all populations, particularly those with a low GBS prevalence [Citation13].

In this study, our objective was to assess the risk of severe neonatal morbidity in the setting of unknown maternal GBS colonization among individuals undergoing cesarean delivery without evidence of labor. We hypothesized that unknown GBS status would be associated with an increased risk of severe neonatal morbidity.

Materials and methods

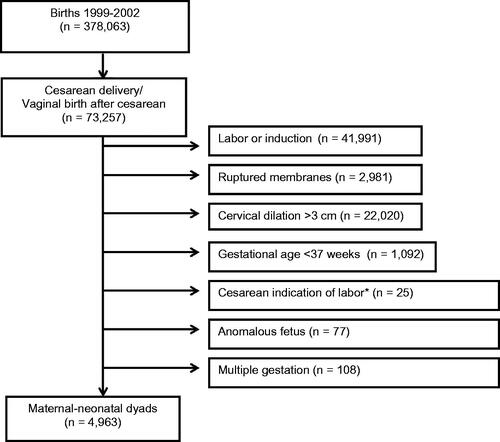

We performed a secondary analysis of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Cesarean Registry. This was a large, multi-center prospective observational study of pregnant individuals with previous cesarean delivery at 19 academic centers from 1999 to 2002 [Citation14]. The goal of the primary study was to determine maternal and neonatal risks associated with a trial of labor after cesarean compared with repeat cesarean delivery. This secondary analysis was reviewed and determined to be exempt by the Institutional Review Board of the University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill.

For the primary analysis, we included individuals with term (≥37 weeks), singleton, non-anomalous gestations undergoing cesarean delivery without evidence of labor. We excluded individuals with evidence of labor, defined as >3cm dilated, evidence of labor by cesarean indication, or evidence of induction. For the primary analysis, we excluded individuals with ruptured membranes. Our exposure was defined by GBS culture status: positive, negative, or unknown. GBS cultures were obtained per individual hospital protocol. Because infants exposed to GBS after ruptured membranes are at a higher risk for GBS acquisition than those with intact membranes, we performed a stratified analysis of individuals with ruptured membranes, but without evidence of labor, as defined above.

The primary outcome was a composite of severe neonatal morbidity and included one or more of the following: clinical or culture-proven sepsis, ventilator support in the first 24 h, respiratory distress syndrome (RDS), hypotension requiring treatment, intubation, necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE), or death. Secondary outcomes included other individual neonatal morbidities: base excess greater than 12 mmol/L, oxygen support without ventilation, transient tachypnea of the newborn, 5-min Apgar score <7, Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) admission, and days in NICU.

Maternal demographics and delivery characteristics were compared by GBS status using chi-square, Student’s t-test, Fisher’s exact, and analysis of variance, as appropriate. Multivariable Poisson regression models with robust variance estimates were used to estimate the association between GBS status and the composite severe neonatal morbidity adjusting for demographic differences (backward stepwise fashion), male sex, and intrapartum antibiotic use. These covariates were chosen a priori from literature review as being associated with the composite outcome. Due to small sample sizes, we did not model individual outcomes. All p-values were derived from a two-sided comparison. All analyses were performed using Stata® version 14.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

In this cohort, 4,963 individuals met inclusion criteria for this study; 3,557 (72%) were of unknown GBS status, 1,255 (25%) individuals were GBS negative, and 151 (3%) were GBS positive (). The three groups differed by the following demographic and baseline characteristics: maternal age, race/ethnicity, tobacco use, body mass index (BMI), maternal medical disease, and number of prior cesareans (, p < 0.05). Compared to GBS negative and unknown individuals, GBS positive individuals were more likely to receive antibiotics for GBS prophylaxis and less likely to receive antibiotics for surgical prophylaxis.

Figure 1. Study cohort selection from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Cesarean Registry.

Table 1. Maternal demographics and delivery characteristics of individuals undergoing cesarean without labor in the MFMU Cesarean Registry by GBS status (N = 4,963), 1999–2002.

There were 289 (5.8%) infants with the severe composite morbidity; 75 (6%) among GBS negative individuals, 6 (4%) among GBS positive individuals, and 208 (5.9%) among individuals with unknown GBS status (not significant, p = 0.61, ). There was no difference in culture proven sepsis among GBS unknown, negative and positive individuals (0.4%, 0.0%, 0.7%, respectively, p = 0.06). GBS positive individuals were more likely to have a neonate with hypotension requiring treatment, but the event rate was small (p = 0.02). The risk of other individual neonatal outcomes were similar among the groups as presented in . In adjusted regression analyses controlling for demographic differences (backward stepwise fashion), male sex, and intrapartum antibiotic use, unknown GBS status was not associated with the composite severe neonatal morbidity, as compared with negative GBS status (adjusted risk ratio, aRR, 0.95 (95% confidence interval, CI, 0.73–1.22, ).

Table 2. Neonatal outcomes among individuals undergoing cesarean delivery without labor and intact membranes* in the MFMU Cesarean Registry (n = 4,963).

Table 3. Multivariable regression model for composite severe neonatal morbidity by GBS status among individuals undergoing cesarean delivery without evidence of labor* in the MFMU Cesarean Registry (n = 4717).

Among individuals undergoing cesarean delivery with ruptured membranes, there were were no significant differences in the severe composite morbidity; 9 (4.8%) among GBS negative individuals, 82 (5.8%) among GBS positive individuals, and 229 (5.7%) among individuals with unknown GBS status (p = 0.85, ). These rates were similar to those seen in the primary analysis (). GBS positive individuals appeared to have higher rates of culture proven sepsis in their infants compared with GBS unknown and negative individuals, but the event rate was small (0.6, 0.4, 0%, respectively, p = 0.05).

Table 4. Neonatal outcomes among individuals undergoing cesarean delivery without evidence of labor* with ruptured membranes in the MFMU Cesarean Registry (n = 5,586).

Discussion

In this secondary analysis of individuals undergoing cesarean section without evidence of labor, we found that GBS status was not associated with the primary composite of severe neonatal morbidity.

Our study adds to the limited information available about GBS status and neonatal risk for individuals delivered via unlabored cesarean. Prior studies of GBS in individuals undergoing cesarean section have focused primarily on infant colonization rates and/or have poorly defined “elective” or “planned” cesarean. In 2006, Berardi et al. examined rates of neonatal colonization (via ear swab) among GBS positive individuals undergoing “planned” cesarean delivery without labor and intact membranes compared to individuals undergoing vaginal delivery [Citation5]. This study found that infants born to individuals in the cesarean group (n = 75) had a 0% rate of colonization compared with 2.4% in individuals undergoing vaginal delivery who received complete antimicrobial chemoprophylaxis and 22.6% in those who received an incomplete course. In 2008, Hakansson et al. also reported infant colonization rates (via combined cheek, umbilicus, groin swab) among individuals undergoing vaginal or cesarean delivery [Citation6]. GBS positive individuals undergoing “acute” cesarean delivery had an infant colonization rate of 30% (10/33) and individuals undergoing “elective” cesarean had an infant colonization rate of 0% (0/29). Notably “acute” and “elective” were not defined. Similarly, Fairlie et al. reported an infant colonization rate of 7% (17/924) among individuals undergoing “non-emergent” cesarean delivery [Citation15]. In 1997, Bramer, et al. reported a decreased risk of early-onset GBS disease among infants born by cesarean section (OR 0.13) but planned versus unplanned cesarean was not defined and confidence intervals were not reported [Citation7]. The retrospective single-hospital study cited by the CDC did not collect maternal GBS or infant cultures, but reported zero cases of GBS-related infection among individuals undergoing planned cesarean delivery (n = 3,546) without labor and intact membranes. This study was only published in abstract form [Citation12].

Our data suggest that maternal GBS screening in individuals undergoing planned cesarean delivery, even in the absence of signs of labor, may not provide clinically useful information predictive of neonatal morbidity. However, in our dataset, the rate of GBS colonization was 33.5% (7,202/21,491). At this prevalence, screening all individuals for GBS regardless of planned delivery mode could prove to be a cost-effective strategy [Citation13]. Furthermore, given that labor is an unpredictable event, screening would allow appropriate chemoprophylaxis for individuals who do not undergo immediate cesarean delivery after labor onset alternatively, rapid GBS testing via nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) could be performed on this small subset of patients.

The strengths of our study are noteworthy. Our work was derived from a large, multi-center, prospective study, increasing the generalizability and power. To our knowledge, this is the first published study to report on a wide range of specific neonatal morbidities in a well-defined cohort of planned, unlabored cesarean deliveries. Additionally, this is one of the largest published studies to date and the only published study from the United States.

The limitations of our work should also be mentioned. The CDC first recommended universal antepartum GBS screening in 2002; the Cesarean Registry concluded in 2002 and thus, screening practices were variable and universal screening was not reliably performed. Infant colonization rates were not available in this study. Additionally, we did not have data regarding neonatal pneumonia or meningitis rates- two important sequelae of neonatal GBS disease. Certain individual neonatal outcomes were too infrequent to assess further. Lastly, we did not have information regarding the speciation of culture-proven sepsis cases.

In conclusion, GBS status prior to planned cesarean does not appear to be associated with composite severe neonatal morbidity. Future research is needed to assess the cost-effectiveness and clinical utility of universal GBS screening in the planned cesarean population and the association of GBS status with other neonatal and maternal outcomes in this population.

Condensation

Unknown GBS status at time of planned cesarean delivery is not associated with severe neonatal morbidity.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Disclosure statement

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network Cesarean Section Registry Database.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Stapleton RD, Kahn JM, Evans LE, et al. Risk factors for group B streptococcal genitourinary tract colonization in pregnant women. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:1246–1252.

- Kleweis SM, Cahill AG, Odibo AO, et al. Maternal obesity and rectovaginal group B Streptococcus colonization at term. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2015;2015:586765–586767.

- CDC GBS Fast Facts. https://www.cdc.govgroupbstrepaboutfast-facts.html.

- Phares CR. Epidemiology of invasive group B streptococcal disease in the United States, 1999–2005. JAMA. 2008;299(17):2056–2065.

- Berardi A, Rossi K, Pizzi C, et al. Absence of neonatal streptococcal colonization after planned cesarean section. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006;85(8):1012–1013.

- Håkansson S, Axemo P, Bremme K, et al. Group B streptococcal carriage in Sweden: a national study on risk factors for mother and infant colonisation. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2008;87(1):50–58.

- Bramer S, van Wijk F, Mol B, et al. Risk indicators for neonatal early-onset GBS-related disease: a case-control study. J Perinat Med. 1997;25(6):469–475.

- Verani JR, McGee L, Schrag SJ, et al. Prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease–revised guidelines from CDC, 2010. MMWR. Recommendations and Reports: morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Recommendations and Reports. 2010;59:1–36.

- Larsen JW, Sever JL. Group B Streptococcus and pregnancy: a review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(4):440. 440-8-discussion 448–50.

- Schuchat A. Impact of intrapartum chemoprophylaxis on neonatal sepsis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22(12):1087–1088.

- Schuchat A. Group B streptococcus. Lancet. 1999;353(9146):51–56.

- Ramus R, McIntire D, Wendell G. Antibiotic chemoprophylaxis for group B strep is not necessary with elective cesarean section at term. Am J Obstetr Gynecol. 1999;180(suppl):85.

- Albright CM, MacGregor C, Sutton D, et al. Group B streptococci screening before repeat cesarean delivery: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(1):111–119.

- Landon MB, Hauth JC, Leveno KJ, et al. Maternal and perinatal outcomes associated with a trial of labor after prior Cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(25):2581–2589.

- Fairlie T, Zell ER, Schrag S. Effectiveness of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis for prevention of early-onset group B streptococcal disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(3):570–577.