Abstract

Objective

To demonstrate the surgical and morbidity differences between upper and lower parametrial placenta invasion (PPI).

Materials and methods

Forty patients with placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) into the parametrium underwent surgery between 2015 and 2020. Based on the peritoneal reflection, the study compared two types of parametrial placental invasion (PPI), upper or lower. Surgical approach to PAS follows a conservative-resective method. Before delivery, surgical staging by pelvic fascia dissection established a final diagnosis of placental invasion. In upper PPI cases, the team attempted to repair the uterus after resecting all invaded tissues or performing a hysterectomy. In cases of lower PPI, experts performed a hysterectomy in all cases. The team only used proximal vascular (aortic occlusion) control in cases of lower PPI. Surgical dissection for lower PPI started finding the ureter in the pararectal space, ligating all the tissues (placenta and newly formed vessels) to create a tunnel to release the ureter from the placenta and placenta suppletory vessels. Overall, at least three pieces of the invaded area were sent for histological analysis.

Results

Forty patients with PPI were included, 13 in the upper parametrium and 27 in the lower parametrium. MRI indicated PPI in 33/40 patients; in three, the diagnosis was presumed by ultrasound or medical background. The intrasurgical staging categorizes 13 cases of PPI performed and finds diagnosis in seven undetected cases. The expertise team completed a total hysterectomy in 2/13 upper PPI cases and all lower PPI cases (27/27). Hysterectomies in the upper PPI group were performed by extensive damage of the lateral uterine wall or with a tube compromise. Ureteral injury ensued in six cases, corresponding to cases without catheterization or incomplete ureteral identification. All aortic vascular proximal control (aortic balloon, internal aortic compression, or aortic loop) was efficient for controlling bleeding; in contrast, ligature of the internal iliac artery resulted in a useless procedure, resulting in uncontrollable bleeding and maternal death (2/27). All patients had antecedents of placental removal, abortion, curettage after a cesarean section, or repeated D&C.

Conclusions

Lower PAS parametrial involvement is uncommon but associated with elevated maternal morbidity. Upper and lower PPI has different surgical risks and technical approaches; consequently, an accurate diagnosis is needed. The clinical background of manual placental removal, abortion, and curettage after a cesarean or repeated D&C could be ideally studied to diagnose a possible PPI. For patients with high-risk antecedents or unsure ultrasound, a T2 weight MRI is always recommended. Performing comprehensive surgical staging in PAS allows the efficient diagnosis of PPI before using some procedures.

Introduction

Placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) is a heterogeneous disease with severe maternal morbidity and fewer severe forms. Therefore, treatment by expert groups implies a relatively low frequency of complications, but highly complex cases may require many hospital resources and lead to severe maternal morbidity [Citation1] and even death [Citation2]. In addition, the location of placental invasion is related to a particular surgical difficulty and morbidity [Citation1], especially when the lower part of the bladder, cervix, or parametrium are involved [Citation3].

Information about PAS with parametrial involvement is negligible [Citation4]. In addition, few existing articles describe the clinical results of these women, almost always mentioning the use of a high number of transfusions [Citation5–7], aortic occlusion [Citation5, Citation7], multiple admissions to the operating theater [Citation8], elevated illness, and long-term severe sequelae [Citation8].

PAS with parametrial placental invasion (PPI) cases implies the involvement of many arterial pedicles through multiple sources, and the obstetrician does not often handle them. Moreover, the parametrial space, mainly located under the peritoneal reflection, is the pelvis’s narrow and deep area near the ureter and multiple vascular structures [Citation7]. Thus, it is necessary to establish management guidelines for PAS specialists and general obstetricians. PPI may be divided into upper or lower cases based on their position with the peritoneal reflection. While upper PPI may only require an average procedure, an inadequate approach to lower PPI could lead to fast, uncontrollable bleeding, severe morbidity, and even mortality [Citation9].

Although PAS is not an actual placental invasion, just a placental protrusion, we continue using the term “invasion” because average readers frequently use it.

We describe the clinical results of PAS cases with parametrial placenta invasion (PPI) in three low- and middle-income countries and propose a sequential approach for management accordingly.

Materials and methods

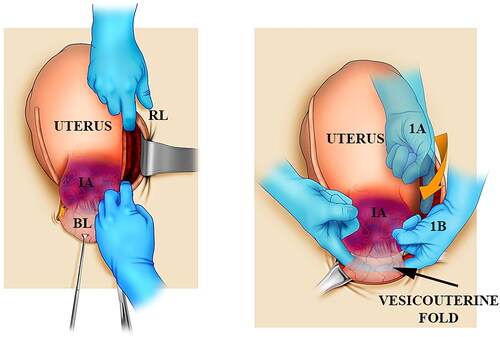

Forty patients with PAS into the parametrium underwent surgery between January 2015 and December 2020. The specialist team received the patients in private, university, and public hospitals in Buenos Aires, Argentina, in the Valle de Lili Foundation, Cali, Colombia, and in the Dr. Soetomo General Hospital, Indonesia. Furthermore, the senior specialist performed a prenatal study image in all the patients, including abdominal, transvaginal ultrasound, and T2 weight, ultrafast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). In addition, the study split patients into two types of PPI groups regarding whether the placental invasion was above (upper) or below (lower) the peritoneal reflection line. The surgical approach to PAS was performed following a general description mentioned by a conservative-resective method [Citation10]. Before delivery, the surgeon performed a pelvic coalesced fascia dissection to achieve a definitive diagnosis of placental invasion. Experts performed surgical staging after cutting inside the round ligament, completed a dissection of the broad ligament folds, and separated the entire vesicouterine fold (). Direct observation of the parametrial space between the two sheets of the broad ligament was classified as follows: class 0, no PPI; class A, PPI-like lateral uterine dehiscence, without strong tissue adherence of neovascularization; and class B, PPI with evidence of newly formed vessels in the placenta or with firm tissue adherence to the pelvic wall.

Figure 1. A scheme showing the basic steps for intrasurgical PAS staging. Left: After cutting the peritoneum medially to the round ligament (RL), fingers open the parametrial space between avascular fascia sheets. Right: From the upper position (A), the index goes down (B) by the subperitoneal tissue until crossing the fingers behind the bladder (BL) to perform a Pelosi maneuver. IA: invaded area.

In upper PPI cases, the surgical team attempts to repair the uterus after resection of invaded tissues or performing a hysterectomy; overall, hemostasis was completed by uterine artery clamping taking part of the myometrium. Which procedure (conservative repair or resective-ablative) was performed depending on the women’s desire for future pregnancy. In cases of lower PPI, experts performed a hysterectomy in all instances. First, the urologist inserted a simple ureteral catheter. In cases of lower PPI, a recurrent stopping to ureteral catheter advance indicated that the procedure should be stopped due to the risk of PPI rupture and massive, unexpected bleeding [Citation11]. Next, the urologist repaired any detected cases of ureteral injuries by resection borders, use of a double J catheter, four stitches for ureteral approximation, and drainage; immediate repair could bring satisfactory surgical results and fewer complications [Citation12]. In cases of hidden ureteral damage, its integrity was reestablished by ureteral reimplantation within 7–10 days. Specialists only used upper proximal vascular control in all patients with lower PPI. In four instances, the vascular surgeons used an elastomeric infrarenal aortic balloon (REBOA™, Prytime Medical, Boerne, TX). In three placed abdominal aortic loops [Citation13], an obstetrician performed internal aortic compression, and in two, a bilateral internal iliac artery was ligated.

Surgical dissection for lower PPI cases started finding the ureter in the pararectal space (Video 1). Then, a surgical retractor separated the round ligament laterally to expose a PPI area covering the ureter (Supplementary Material 1, F1). Later, the surgeon ligated the placenta and newly formed vessels above the ureter using Vicryl number 0 (Supplementary Material 1, F2), creating a tunnel to release the ureter from the placenta and connecting vessels. Due to the pelvic ureteral blood supply coming to the lateral side, ligatures must be applied internally to the ureter (Supplementary Material 1, F3). Then, the PPI is wholly separated to perform hysterectomy [Citation14], reducing the risk of unexpected bleeding.

In all cases, at least three pieces of the invaded area were sent for histological analysis. Continuous statistical variables were expressed as medians and interquartile ranges and analyzed with the Mann–Whitney U-test. Categorical variables included proportions and comparisons using the Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test (Statistical Package Stata, version 14.0, StataCorp., College Station, TX). Approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee under protocol number 550-2015.

Discussion

Main findings

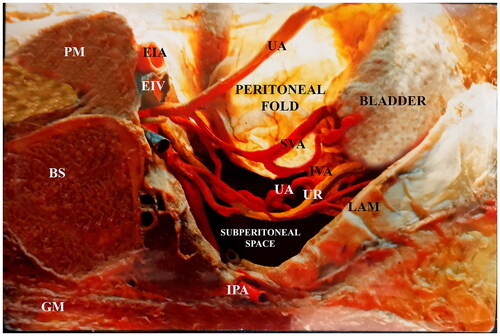

Lower parametrial PAS involvement is an infrequent but potentially life-threatening situation [Citation15]. At surgery, the surgical team confirmed 40 cases of PPI, 13 in the upper parametrium and 27 in the lower parametrium. MRI indicated PPI in 21/32 patients; in seven, the identification was performed by surgical staging, and in three, the diagnosis was presumed by ultrasound [Citation16]. False-positive ultrasound interpretations resulted in cases in which accreta were suspected to be a clinical concern but turned out to not be present [Citation17]. Conversely, false-negative readings may lead to a circumstance with unanticipated complications or tragic consequences [Citation18]; for this reason, high-risk patients must be operated on as PAS-positive to decrease maternal morbidity [Citation19]. The coexistence of MRI signs in the lateral uterine wall was associated with an elevated risk of bleeding [Citation20] and complications [Citation21]; an MRI study would facilitate preoperative planning and evaluation of maternal outcomes in most cases with maternal risk factors. Therefore, MRI should be used for at-risk patients to accurately identify the placental location, regardless of the ultrasonography results. The intrasurgical staging categorizes the position and features of the invaded placenta and newly formed between the lateral uterus and the iliac internal vascular fascia ().

Figure 2. Parasagittal cut on the right female pelvis. An embalmed corpse, the peritoneal sheet of the parametrium was transilluminated. Notice that the parametrium in a straight space has plenty of arteries, veins, and the ureter.

All PPIs had a medical background, for instance, manual removal of the placenta [Citation22], iterative D&C [Citation23], and curettage after cesarean section or abortion [Citation24]. Lower PPI showed more complications, blood loss, a requirement of proximal vascular control, longer operative time, and urinary injuries than upper PPI (). The possibility of unexpected massive bleeding increases in lower PPI; heavy bleeding is associated with the presence of newly formed vessels but not connected with the size of the lower PPI (Supplementary Material F4). Surgical diagnosis of lower PPI with the mentioned features means the rise of unwanted blood loss [Citation7] and the alert to stop any dissection until aortic vascular control is performed. The efficiency of aortic vascular management was directly associated with its application, obtaining the best results when used before and not during or after the parametrial dissection. The use of iliac internal vascular control resulted in uncontrollable massive bleeding and fasted and not immediately recognized blood loss volume [Citation25,Citation26], coagulopathy, and metabolic acidosis that lead to two cases of maternal death. In both cases, the surgical team underestimated a small piece of lower PPI and surprised by uncontrollable bleeding despite bilateral internal iliac vascular control. During active bleeding or persistent oozing, damage control surgery [Citation27] was attempted using pelvic packing. However, it was completely useless because blood and clots went unsuspectingly through pelvic subperitoneal spaces and retroperitoneal areas (Supplementary Material F5). In upper PPI, control bleeding was efficiently controlled only using uterine vessel compression (Supplementary Material F6). In all cases of upper PPI, the uterine repair was technically possible, but the decision for a resective procedure was the final choice of the obstetrician according to the mother’s preferences. All cases of ureteral ligature occurred in patients without ureteral catheterization due to complete identification; then, the ureter was reimplanted [Citation28] within 7–10 days without further complications.

Table 1. Clinical results of patients with upper and lower type 2 PAS placenta invasion.

Internal manual compression of the aorta effectively controls pelvic bleeding in unexpected parametrial bleeding and facilitates dissection maneuvers. Histology analysis confirmed PAS, and over 120 samples (three samples from 40 cases) were collected in a 100% placenta percreta. PAS is not an authentic invasion but just a placental protrusion, although morbidity and blood loss are closely associated with the invasion topography and not with a placental degree invasion [Citation10].

Strengths and limitations

The study’s main strength is that is we collected a high number of cases of this uncommon PAS location. The use of aortic vascular control and precise ureteral dissection demonstrated safety and decreased blood loss [Citation29] in patients with a lower PPI. Compared to existing papers, this study represents the most extensive series about PPI and could be an outstanding guide for experts and beginners. A surgical guide in severe cases of PAS proposes an alternative to leaving the placenta in situ; although, this option is connected with severe maternal morbidity, especially in placenta percreta [Citation30]. The main limitation of our study is a poor comparison with other publications because they are only a few case reports. Furthermore, lower PPI is connected with hazardous surgery, massive and uncontrollable bleeding, severe maternal morbidity, and even death; probably by this cause, hospitals or doctors are not prone to publish their results.

Moreover, the low frequency of PPI made it impossible to collect information from centers with limited PAS cases by year. Although Argentina legalized abortion some years ago, Argentina, Colombia, and Indonesia are countries with a high rate of unlawful abortions, procedures closely connected to uterine damage. Maternal mortality in percreta is approximately 7% [Citation31], but this is a general value; this rate is likely significantly higher in lower PPI. Although the publication appears to be substantial, the relative values for PAS complications are not enough to estimate a real statistical significance [Citation32].

Interpretation

The presence of newly formed vessels or a direct placental attachment (without serosa) in the lower PPI indicated the possibility of uncontrollable massive bleeding [Citation33] independent of extrauterine placenta size. Lower PPI bleeding is associated with challenging hemostasis, first by the diversity of their blood supply source [Citation34] and second by the particularly deep and narrow placental invasion anatomy. Upper PPI seems impressive, but it is not technically difficult to handle when performing expertise groups. Due to the thick and healthy myometrium in the upper uterus concerning the lower PPI, the use of aortic vascular control is only recommended in cases of lower PPI, especially in the presence of newly formed vessels or firm placental adherence to iliac internal elements. First, the newly formed vessels have multiple connections with the lower anastomotic circle [Citation35]; second, the possibility of undiagnosed extension to the ischiorectal through the levator ani muscle (roof of the ischiorectal fossae) is unknown until deep dissection.

The concomitant use of aortic vascular control and ureteral-specific dissection is safe to minimize the surgical risk in lower PPI. It is expected that the surgeons handling a complicated case of PAS think to avoid touching the placenta and leaving it in situ as a definitive treatment or addressing it later with a delayed hysterectomy. In the case of early and massive, unexpected bleeding, a surgical solution is problematic, first, due to placental placement and second, due to the risk of coagulopathy, hypovolemic shock, and metabolic acidosis. In these cases, primary aortic vascular control is a priority to have time to replace volume, restore a clot, and stabilize hemodynamic parameters [Citation36]. Although unpublished, massive embolization by lower PPI is not recommended in the case of a wide pelvic and extra pelvic anastomotic net [Citation37]. Although there are some prospective randomized trials [Citation38,Citation39], retrospective cohort and physiology research about the internal iliac ligature [Citation40], and studies that have demonstrated its inefficacy in cases of pelvisubperitoneal bleeding, the use of internal iliac artery occlusion is associated with severe complications [Citation41–43] and even death [Citation44,Citation45].

Conversely, the aortic vascular control below renal arteries blocks the iliac internal, external, some aortic, and femoral anastomotic components bilaterally in a simple way. Consequently, it is an invaluable tool to achieve hemostasis in lower PPI. Comparable efficacy of aortic blocking has been demonstrated using a specific aortic balloon, an aortic cross-clamp [Citation46], or inexpensive aortic slinging [Citation13].

Conclusions

Lower PAS parametrial involvement is uncommon but is associated with elevated maternal morbidity. Upper and lower PPI have different surgical risks and require different technical approaches; consequently, accurate identification is greatly needed.

Women with a clinical background of manual placental removal, abortion, or repeated D&C must be carefully examined to diagnose a possible PPI. For patients with high-risk antecedents or doubtful ultrasound, a T2 weight MRI is recommended. Performing comprehensive surgical staging in PAS allows the efficient diagnosis of PPI efficiently and before using any dissection maneuvers that cause unexpected massive bleeding. Knowing what to do or not do is essential for avoiding unnecessary organ ablation and uncontrollable massive bleeding.

Author contributions

Palacios-Jaraquemada JM contributed to the conception, planning and carrying out analysis, and writing up of this work. Nieto-Calvache A, Aditya Aryananda R, and Basanta N contributed to carrying out, analyzing, and correcting the manuscript.

Supplemental Material

Download MP4 Video (4.9 MB)Supplemental Material

Download MP4 Video (209.8 MB)Supplemental Material

Download PDF (993.2 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank Fabián Cabrera, graphic design program Professor, from Universidad del Valle, Cali, Colombia.

Disclosure statement

Palacios Jaraquemada JM is an Editorial Board of the Journal of Maternal, Fetal, and Neonatal Medicine. Basanta N, Nieto-Calvache A, and Aditya Aryananda R have no conflicts of interest to declare. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were performed according to the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committees. Informed consent was obtained from the patients included in the study. The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Kingdom JC, Hobson SR, Murji A, et al. Minimizing surgical blood loss at cesarean hysterectomy for placenta previa with evidence of placenta increta or placenta percreta: the state of play in 2020. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223(3):322–329.

- Nieto-Calvache AJ, Palacios-Jaraquemada JM, Osanan G, et al. Lack of experience is a main cause of maternal death in placenta accreta spectrum patients. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021;100(8):1445–1453.

- Palacios-Jaraquemada JM, D'Antonio F, Buca D, et al. Systematic review on near-miss cases of placenta accreta spectrum disorders: correlation with invasion topography, prenatal imaging, and surgical outcome. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020;33(19):3377–3384.

- Palacios Jaraquemada JM, Bruno CH. Magnetic resonance imaging in 300 cases of placenta accreta: surgical correlation of new findings. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2005;84(8):716–724.

- Al-Omari W, Elbiss HM, Hammad FT. Placenta percreta invading the urinary bladder and parametrium. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;32(4):396–397.

- Borekci B, Ingec M, Kumtepe Y, et al. Difficulty of the surgical management of a case with placenta percreta invading towards parametrium. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2008;34(3):402–404.

- Seoud M, Cheaib S, Birjawi G, et al. Successful treatment of severe retroperitoneal bleeding with recombinant factor VIIa in women with placenta percreta invading into the left broad ligament: unusual repeated antepartum intra-abdominal bleeding. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2010;36(1):183–186.

- Vahdat M, Mehdizadeh A, Sariri E, et al. Placenta percreta invading broad ligament and parametrium in a woman with two previous cesarean sections: a case report. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2012;2012:251381.

- Zhu B, Yang K, Cai L. Discussion on the timing of balloon occlusion of the abdominal aorta during a caesarean section in patients with pernicious placenta previa complicated with placenta accreta. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:8604849.

- Palacios-Jaraquemada JM, Fiorillo A, Hamer J, et al. Placenta accreta spectrum: a hysterectomy can be prevented in almost 80% of cases using a resective-reconstructive technique. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022;35(2):275–282.

- Dyer RB, Chen MY, Zagoria RJ, et al. Complications of ureteral stent placement. Radiographics. 2002;22(5):1005–1022.

- Rao D, Yu H, Zhu H, et al. The diagnosis and treatment of iatrogenic ureteral and bladder injury caused by traditional gynaecology and obstetrics operation. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012;285(3):763–765.

- Long ML, Cheng CX, Xia AB, et al. Temporary loop ligation of the abdominal aorta during cesarean hysterectomy for reducing blood loss in placenta accrete. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;54(3):323–325.

- Takeda S, Takeda J, Murayama Y. Placenta previa accreta spectrum: cesarean hysterectomy. Surg J. 2021;7(Suppl. 1):S28–S37.

- Chen X, Shan R, Song Q, et al. Placenta percreta evaluated by MRI: correlation with maternal morbidity. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2020;301(3):851–857.

- Calì G, Foti F, Minneci G. 3D power Doppler in the evaluation of abnormally invasive placenta. J Perinat Med. 2017;45(6):701–709.

- Bowman ZS, Eller AG, Kennedy AM, et al. Accuracy of ultrasound for the prediction of placenta accreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211(2):177.e1–177.e7.

- Nageotte MP. Always be vigilant for placenta accreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211(2):87–88.

- Reeder CF, Sylvester-Armstrong KR, Silva LM, et al. Outcomes of pregnancies at high-risk for placenta accreta spectrum following negative diagnostic imaging. J Perinat Med. 2022;50(5):595–600.

- Bourgioti C, Zafeiropoulou K, Fotopoulos S, et al. MRI prognosticators for adverse maternal and neonatal clinical outcome in patients at high risk for placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) disorders. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2019;50(2):602–618.

- Woodward PJ, Kennedy AM, Einerson BD. Is there a role for MRI in the management of placenta accreta spectrum? Curr Obstet Gynecol Rep. 2019;8(3):64–70.

- Sivasankar C. Perioperative management of undiagnosed placenta percreta: case report and management strategies. Int J Womens Health. 2012;4:451–454.

- Cooper AC. The rate of placenta accreta and previous exposure to uterine surgery. Yale Medicine Thesis Digital Library; 2012. p. 1702. Available from: http://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ymtdl/1702

- Harris LH, Grossman D. Complications of unsafe and self-managed abortion. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(11):1029–1040.

- Bhananker SM, Ramaiah R. Trends in trauma transfusion. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2011;1(1):51–56.

- Hancock A, Weeks AD, Lavender DT. Is accurate and reliable blood loss estimation the 'crucial step’ in early detection of postpartum haemorrhage: an integrative review of the literature. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:230.

- Carvajal JA, Ramos I, Kusanovic JP, et al. Damage-control resuscitation in obstetrics. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022;35(4):785–798.

- Rizvi JH, Zuberi NF. Prevention and treatment of urinary tract injuries during obstetrics and gynaecological procedures. In: Ratnam SS, editor. Textbook of obstetrics and gynecology for post-graduates. Vol. 2. London: Orient Longman; 2003. p. 366–374.

- Soleymani Majd H, Collins SL, Addley S, et al. The modified radical peripartum cesarean hysterectomy (Soleymani-Alazzam-Collins technique): a systematic, safe procedure for the management of severe placenta accreta spectrum. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225(2):175.e1–175.e10.

- Marcellin L, Delorme P, Bonnet MP, et al. Placenta percreta is associated with more frequent severe maternal morbidity than placenta accreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219(2):193.e1–193.e9.

- O'Brien JM, Barton JR, Donaldson ES. The management of placenta percreta: conservative and operative strategies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175(6):1632–1638.

- Leppink J, Winston K, O'Sullivan P. Statistical significance does not imply a real effect. Perspect Med Educ. 2016;5(2):122–124.

- Ishibashi H, Miyamoto M, Iwahashi H, et al. Criteria for placenta accreta spectrum in the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics Classification, and topographic invasion area are associated with massive bleeding in patients with placenta previa. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021;100(6):1019–1025.

- Palacios-Jaraquemada JM, García-Mónaco R, Barbosa NE, et al. Lower uterine blood supply: extrauterine anastomotic system and its application in surgical devascularization techniques. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007;86(2):228–234.

- González J, Albeniz LF, Ciancio G. Vascular problems of the pelvis. In: Lanzer P, editor. PanVascular medicine. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2015. p. 3793–3820.

- Palacios-Jaraquemada J, Fiorillo A. Conservative approach in heavy postpartum hemorrhage associated with coagulopathy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010;89(9):1222–1225.

- Brătilă E, Brătilă CP, Coroleucă CB, et al. Collateral circulation in the female pelvis and the extrauterine anastomosis system. Rom J Anat. 2015;14(2):223–227.

- Yu SCH, Cheng YKY, Tse WT, et al. Perioperative prophylactic internal iliac artery balloon occlusion in the prevention of postpartum hemorrhage in placenta previa: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223(1):117.e1–117.e13.

- Hussein AM, Dakhly DMR, Raslan AN, et al. The role of prophylactic internal iliac artery ligation in abnormally invasive placenta undergoing caesarean hysterectomy: a randomized control trial. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;32(20):3386–3392.

- Burchell RC. Internal iliac artery ligation: hemodynamics. Obstet Gynecol. 1964;24:737–739.

- Gandhi MR, Kadikar GK. Laceration of the internal iliac vein during internal iliac artery ligation. Natl J Med Res. 2013;3(2):190–192.

- Gagnon J, Boucher L, Kaufman I, et al. Iliac artery rupture related to balloon insertion for placenta accreta causing maternal hemorrhage and neonatal compromise. Can J Anaesth. 2013;60(12):1212–1217.

- Dzsinich C. Ligation of the large vessels in the pelvis. CME J Gynecol Oncol. 2004;9:38–40.

- Oderich GS, Panneton JM, Hofer J, et al. Iatrogenic operative injuries of abdominal and pelvic veins: a potentially lethal complication. J Vasc Surg. 2004;39(5):931–936.

- Burchell RC, Mengert WF. Internal iliac artery ligation: a series of 200 patients. J Int Fed Obstet Gynecol. 1969;7(2):85–92.

- Stubbs MK, Wellbeloved MA, Vally JC. The management of patients with placenta percreta: a case series comparing the use of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta with aortic cross clamp. Indian J Anaesth. 2020;64(6):520–523.