Abstract

Objective

To measure the prevalence of maternal anxiety, depression and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in those exposed to natural disasters.

Methods

A literature search of the PubMed database and www.clinicaltrials.gov from January 1990 through June 2020 was conducted. A PRISMA review of the available literature regarding the incidence and prevalence of maternal anxiety, depression and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) following natural disasters was performed. A natural disaster was defined as one of the following: pandemic, hurricane, earthquake and post-political conflict/displacement of people. Studies were selected that were population-based, prospective or retrospective. Case reports and case series were not used. The primary outcome was the prevalence of maternal anxiety, depression and PTSD in the post-disaster setting. Two independent extractors (I.F. & H.G.) assessed study quality using an adapted version of the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment tool. Given the small number of studies that met inclusion criteria, all 22 studies were included, regardless of rating. Data were extracted and aggregate rates of depression, anxiety, and PTSD were calculated to provide synthesized rates of maternal mental health conditions among participants.

Results

Twenty-two studies met the inclusion criteria. A total of 8357 pregnant or birthing persons in the antepartum and postpartum periods were studied. The prevalence of post-pandemic anxiety, depression and PTSD were calculated to be 48.2%, 27.3%, and 22.9%. Post-earthquake depression and PTSD rates were 38.8% and 22.4%. The prevalence of post-hurricane anxiety, depression and PTSD were 17.4%, 22.5%, and 8.2%. The rates of post-political conflict anxiety, depression and PTSD were 48.8%, 31.6% and 18.5%.

Conclusion

Given the high rates of anxiety, depression and PTSD among pregnant and birthing persons living through the challenges of natural disasters, obstetrician-gynecologists must be able to recognize this group of patients, and provide a greater degree of psychosocial support.

Introduction

Perinatal depression which occurs during pregnancy or in the first 12 months after delivery, is one of the most common medical complications during pregnancy and the postpartum period, affecting one in seven women [Citation1]. In 2011, 9% of pregnant persons and 10% of postpartum persons met the criteria for major depressive disorders [Citation1]. In the United States, up to 51% of people with perinatal depression are undiagnosed [Citation2]. The reported prevalence of anxiety in the perinatal period ranges widely with recent meta-analyses estimating a range between 8.5% to 15.2% prenatally and 9.9% postnatally with some of these studies also including PTSD [Citation3].

Despite the availability of tools to screen for perinatal depression, there is no consensus on which tool is most accurate, nor is there a universal policy on when and how to best screen patients with perinatal depression [Citation4,Citation5]. Untreated perinatal depression, anxiety and posttraumatic stress disorders (PTSD) can have devastating effects on both the parent and child [Citation1]. One example is the correlation with ADHD in children of mothers in the top 15% of symptoms of antenatal anxiety having twice the risk for ADHD at ages 4 and 7 [Citation3]. There have been studies finding low birth weight, as well as preterm deliveries associated with depressive disorder [Citation6]. Pregnant persons with anxiety have been found to have increased uterine artery resistance, which is associated with fetal growth restriction and preeclampsia [Citation6]. In 2019, the US Preventive Task Force changed its recommendation for adult depression screening in the general adult population to include pregnant and postpartum persons [Citation1,Citation7].

Studies have identified the major risk factors for maternal mental health disorders, especially postpartum depression, including low socioeconomic status, poor social support, immigrant status, marginalization in society, history of substance abuse disorders, additional mental health disorders, and stressful life events, such as natural disasters. Additionally, those with mental health conditions, including antepartum and postpartum depression and anxiety, have decreased bonding with their infants, low birth weight infants, and higher rates of mood disorders in their children [Citation6]. This paper aims to help fill the current gap in the literature pertaining to the relationship between natural disasters and maternal mental health disorders.

Objective

More recently, studies have examined the prevalence of maternal anxiety, depression and PTSD in the context of a world-wide pandemic. COVID-19 is the most recent of the many natural disasters to be researched as a potential contributor to mental health diseases [Citation8–12]. The purpose of this paper is to present a focused review of the available data on the overall prevalence of maternal mental health morbidities by comparing rates of mental health disease in the pre and -post-exposure to natural disaster cohorts and to describe the overall risk in patients exposed to natural disasters.

Materials and methods

Search strategy and information sources

The Quality of Reporting of Meta-analysis standards were followed using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews checklist [Citation13]. A search of the PubMed database and www.clinicaltrials.gov from January 1990 through June 2020 was conducted using the keywords “maternal anxiety and depression,” “maternal PTSD,” “natural disaster,” “Katrina,” “Sandy,” “Hurricane,” “Harvey,” “earthquake,” “tsunami,” “pandemic,” “HIV,” “COVID-19,” “SARS,” “H1N1,” “Spanish influenza,” and “refugees.”

Eligibility criteria

To be included, studies had to report original data on the association between exposure to natural disasters and the following maternal mental health diseases: anxiety, depression and PTSD. Studies had to be published in a peer-reviewed journal in the English language. Studies were excluded if they did not describe the prevalence of maternal mental health disease following a natural disaster as an outcome of the study. Case series and case reports were excluded.

Data quality assessment

Two independent extractors (I.F. & H.G.) assessed study quality using an adapted version of the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment tool [Citation14]. Studies were rated as strong, moderate, or weak based on study design, selection bias (response rate, representativeness), confounding (percentage of confounders controlled for), detection bias (outcome measure validity), and attrition bias (loss to follow-up, missing data). Nevertheless, given the small number of studies that met inclusion criteria, all 22 studies were included, regardless of rating.

Assessment of risk of bias

All reports were considered regardless of obstetrical or demographic characteristics. Two authors (I.F. & H.G.) independently extracted information on the prevalence, risk factors, outcomes and screening methods, obtaining similar search results. When the studies not conforming to the preestablished eligibility and inclusion criteria were excluded, the same study investigators (I.F. & H.G.) independently reviewed the data collection for a second time.

Data extraction

When available, the rates of maternal mental health conditions were recorded. Since no tool has been established as the most accurate or as the standard of care for screening for maternal anxiety, depression and PTSD [Citation4,Citation5], this review compiled and included all tools used worldwide to screen for maternal depression, anxiety and PTSD. This review is exempt from institutional review board approval because of the research design as a review article. The majority of articles were either cross-sectional studies or cohort studies. Data from systematic reviews were extracted from individual studies if reported, but not in aggregate. The prevalence of maternal mental health morbidities in the pre-disaster population was gathered using the pre-disaster cohorts, while post-disaster prevalence was gathered using the post-disaster cohorts and those investigated in cross-sectional post-disaster studies. The numbers of those with and without each disorder were summed across studies and the average rates were calculated. The prevalence of each mental health disease was then compared to pre-disaster cohorts, when available, using the Chi square test for categorical nominal data. A p Value <.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

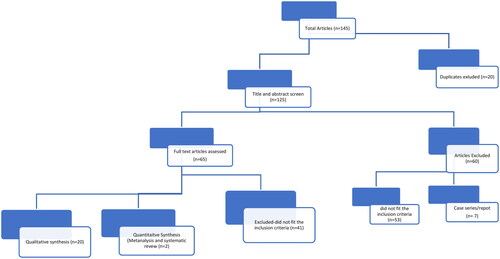

A total of 145 abstracts were reviewed based on the keyword search criteria. Out of 145 results, 20 were duplicates. One hundred twenty-five titles and abstracts were screened, out of which 60 studies were excluded (53 did not meet inclusion criteria and seven were case reports and case series) (). Studies selected were population-based, prospective or retrospective.

Twenty-two studies met the inclusion criteria and are summarized in . Five studies had perinatal depression rates as their primary outcome; five described the rates for both depression and anxiety; eight studies evaluated depression and PTSD rates; and four described the rates of depression, anxiety and PTSD. There was a single study that examined the rates of PTSD alone and a single study that described the prevalence of anxiety alone. There were five case-control studies, seven cross-sectional studies, nine cohort studies and one systematic review.

Table 1. Studies of maternal mental health morbidities organized by type of natural disaster.

Data were extracted for synthesis from 18 of the 22 studies. One study was not included due to data presented as trajectories [Citation15]. Three articles included data from populations that were in prior publications and therefore were excluded [Citation16–18]. The data was included in the original publications [Citation19–21]. Data presented in the systematic review was included after ensuring that the data had not been previously included in another study [Citation22–25]. The aggregated prevalence and rates of depression, anxiety and PTSD based on the type of natural disaster are summarized in .

Table 2. Rates of depression, anxiety and ptsd in each type of natural disaster.

A total of 8357 pregnant and birthing persons in the antepartum and postpartum periods were studied. Of those, 1281 were in the pre-disaster cohorts and 7248 were included in the post-disaster cohorts. The primary outcomes are summarized in . The prevalence of post-pandemic anxiety, depression and PTSD were calculated to be 48.2%, 27.3%, and 22.9%. These rates were significantly higher than pre-pandemic cohorts. Post-earthquake depression and PTSD rates were 38.8% and 22.4%. Post-earthquake anxiety rates were not available to comment on. The prevalence of post-hurricane anxiety, depression and PTSD were 17.4%, 22.5%, and 8.2%. The rates of post-political conflict anxiety, depression and PTSD were 48.8%, 31.6%, and 18.5%. P values were recorded when a pre- and post-disaster prevalence were available. The baseline prevalence of each mental health disease by country of article origin was also included (see ). Secondary outcomes were the adverse outcomes from pregnancies complicated by mental health conditions following exposure to natural disasters, and are summarized in . Previous literature quotes the rate of preterm birth in the general population of the United States at 12.7% and the rate of alcohol abuse in pregnancy at 10.2% [Citation49,Citation50]. The association of alcohol abuse and preterm birth with depression, anxiety and PTSD in subjects exposed to natural disasters is unclear and further investigation is warranted.

Table 3. Secondary outcomes.

Comment

Main findings

Pandemics

Financial instability, forced isolation and the commonality of disease will undoubtedly contribute to the widespread emotional distress and increased risk for psychiatric illness associated with COVID-19. When examining psychiatric disorders following worldwide pandemics, several studies discuss prevalence and screening tools and offer management solutions to decrease the severity of mental health diseases among pregnant patients exposed to infectious causes of global unrest. Pre and post-terminology refers to the relationship between the onset of the disaster and the time period in which patients were studied for psychopathology. To clarify, “post” does not necessarily mean post-disaster. The rates of psychopathology in relation to COVID 19 were assessed at the height of the pandemic with no clear timeline of resolution and unique based on its global impact. The true rates of psychopathology during the aftermath of the COVID 19 are yet to be known.

Anxiety

Studies whose primary outcome was the prevalence of anxiety have noted that the trigger for anxiety in most cases was fear of vertical transmission, as well as the spread of disease to family and friends [Citation29]. Three studies used the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) questionnaire. In the first, the overall prevalence of STAI >36 (above normal anxiety) was 68% (68 of 100). More than half of pregnant persons rated the psychological impact of the COVID-19 outbreak as severe, and two-thirds reported higher-than-normal anxiety [Citation29]. In the second, moderate to high anxiety (STAI-state score >40) was identified in 72% of the cases compared with 29% in the pre-COVID-19 pandemic control [Citation30]. A third study found that the SARS cohort had significantly higher anxiety STAI-state scores than the pre-SARS cohort (37.2 ± 9.7 vs. 35.5 ± 9.3, p =.02) [Citation36].

A second standardized tool used to assess maternal anxiety was the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI). The BAI is a summation of ratings of 21 clinical anxiety symptoms experienced by patients in a previous month, scored on a scale of 0 to 63 of increasing severity [Citation27]. In this study, the initial step was to separate cases and controls by their Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale (EPDS) score (>/<13). Higher BAI scores were found among those who screened positive with EPDS scores >13 (mean BAI score of 22.087 ± 8.689 vs.8.607 ± 5.988 p < .001). Social isolation exerted a statistically significant influence on the EPDS and BAI scores of the participants [Citation27].

Depression

Perinatal depression has been linked to both maternal and fetal adverse outcomes including preterm delivery, fetal growth restriction, as well as the long-term consequences of increased risk of future anxiety and depression and cognitive delays for the offspring [Citation30,Citation1–53]. Although clinical diagnosis and treatment via psychological or pharmacological treatment remain front line as therapeutic approaches, the COVID-19 pandemic has introduced a new challenge, namely, reduced access and/or attendance to health care visits [Citation54].

Similar to anxiety, the prevalence of depression has been studied using different screening tools. One study examined depression prevalence using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Survey [Citation30]. An EPDS score >13 (indicative of depression) was self-identified in 15% of controls pre-pandemic and in 40.7% who were exposed to the COVID 19 pandemic (7.5 ± 4.9 vs. 11.2 ± 6.3, respectively; p < .01) [Citation30]. Similarly, a study compared the rates of depression during COVID-19 using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and the EPDS and found significant correlations between BDI and EPDS scores and between social isolation and both BDI and EPDS scores (p < .01) [Citation27]. While high rates of depression have been found in the COVID-19 literature, a study that compared pre-SARS to post-SARS cohorts did not find a difference in perinatal depression rates [Citation36]. In studies on the reliability and accuracy of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) scale in HIV infected patients, HIV-infected pregnant persons scored 6.2 points higher on the CES-D than HIV-uninfected persons (p = .032) [Citation32]. A different study examined the prevalence of depression among HIV positive persons using the CES-D, which was calculated at 50% [Citation34].

PTSD

A single study examined PTSD among pregnant patients in the context of a pandemic. The sample included 70 mother–child dyads, each being HIV infected. It described the self-reported prevalence of PTSD among HIV-positive mothers using the Harvard Trauma Scale (HTS), which was calculated to be 22.9% [Citation34].

Earthquakes

PTSD and depression have mainly been reported in those who have lived through these traumatic events [Citation40,Citation41]. Four studies investigated the impact of earthquake exposure on patients in the antepartum and immediate postpartum periods [Citation38,Citation40,Citation41,Citation55]. The earthquakes include the 2008 Sichuan earthquake in China, the 1999 Taiwan earthquake, and the 2007 Noto Peninsula earthquake in Japan [Citation38, 0,Citation41,Citation55].

Depression

Three studies examined depression as the primary outcome with two using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) for screening [Citation40,Citation41], whereas the third study used the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) [Citation38].

Pregnant persons in the Noto region of Japan three to ten months after a 2007 earthquake were also studied. Ninety-nine women were surveyed with the EPDS before and after delivery. Multiple logistic regression analysis showed that persons’ EPDS scores after delivery were significantly correlated with ‘existing anxiety about an earthquake’ (p < .01), parity (p < .01), and EPDS during pregnancy (p < .01). The mean level of EPDS for the study participants after delivery was 3.8 ± 4.1, and the percentage of high-risk individuals (those with an EPDS score >9 points) was 13.1% before delivery and 8.1% after. When compared to the general population in Japan, this is lower than a previously reported prevalence of postnatal depression (13.9%), which may be explained by a generally low prevalence in the rural Noto area or by the earthquake having little psychological impact [Citation41].

In a second study, 311 pregnant persons living in the Sichuan province of China were surveyed 18 months after the 2008 earthquake with the EPDS (>9). The rate of major depression was 40.8% (95% CI, 35.5–46.4). The risk of depression increased with an increase in the stresses of pregnancy (OR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.12–1.27; p < .001) and decreased with strong familial support (OR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.73–0.98; p = .022). Persons between the ages of 18 to 24 years old had a lower risk of depression than those older than 30 years (OR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.20–0.90; p = .025) [Citation40].

CES-D was used in a study in which the screening scores formed different risk groups, that is, those with little or no symptoms of depression (CES-D score <16), mild depressive symptoms (16–20), moderate depressive symptoms (21–25), and severe depression (≥26). According to this cutoff scale, 29% (95% CI, 24.3–34.3) of 317 studied persons had depressive symptoms, and of these, 14.2% (95% CI, 10.8–18.5) met the criteria of moderate depression or severe depression within one week after delivery [Citation38].

PTSD

Three studies described the prevalence of PTSD after earthquakes. Two studies used Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R) [Citation40,Citation41], and the third study used the Post-traumatic Stress Reaction Checklist (PTSRC) [Citation55]. One study using the IES-R interviewed 317 persons who had delivered within one week in the location of the earthquake with varying levels of exposure; the overall prevalence rate of PTSD was 19.9%. By DSM-IV criteria, 9.5% (95% CI, 6.7–13.2) were diagnosed with full PTSD with scores on all three subscales of the IES-R equal to or greater than 1.8. The prevalence of partial PTSD was met in 10.4% (95% CI, 7.5–14.3) by scoring on any two subscales equal to or greater than 1.8. Both full and partial PTSD were included in prevalence calculations. The study found that individuals with high earthquake exposure had higher rates of PTSD (odds ratio 5.91, 95% CI 1.75–19.97, p < .001) [Citation40].

Another study looked at PTSD measured with the IES-R in 311 pregnant persons during the 18 months after the 2008 Sichuan province earthquake in China. The prevalence rate of PTSD symptoms was 12.2% (95% CI, 9.0–16.4). PTSD was directly correlated with pregnancy-related stress (OR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.07– 1.32; p = 0.001) and increased exposure to the earthquake (OR, 1.80; 95% CI, 1.43–2.26; p < 0.001). Patients ages 18–24 years old had lower rates of PTSD (OR, 0.10, 95% CI, 0.03–0.31; p < 0.001). Higher levels of PTSD were correlated with the death of a family member and witnessing others being trapped under ruins [Citation41].

A final study looked at PTSD in current pregnant persons six months after an earthquake in Taiwan in 1999, measured by the PTSRC, and also looked at perinatal outcomes and minor psychiatric morbidity. In 171 surveyed pregnant persons, 9.3% rated ‘profound’ on ‘impact on mood’ and ‘impact on daily function.’ Of the patients who scored higher than three groups in the Chinese Health Questionnaire (CHQ-12), 29.2% were found to have a minor psychiatric disease. These patients all had higher PTSD scores [Citation55].

Hurricanes

Seven studies were identified that address maternal psychological outcomes after exposure to Hurricanes Katrina and Sandy [Citation15–21,Citation56].

Anxiety

Two studies examined anxiety in pregnancy after a hurricane [Citation16,Citation19]. Both studies used the Revised Prenatal Distress Questionnaire to evaluate for prenatal anxiety. It is a 17-item survey using a Likert scale with scores >17 suggesting prenatal anxiety [Citation19]. The first study qualitatively evaluated pregnant persons’ mental health, psychosocial concerns and sources of stress living in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina [Citation16]. The authors found higher scores of pregnancy-related anxiety (17.41) and perceived stress (17.66). In the second study performed by the same investigators in the same group of patients, 402 pregnant persons living in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina were interviewed to assess for post-disaster maternal mental health, and to determine if the use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) affected the rates of maternal mental health morbidity [Citation19]. Overall, this study found no significant associations between CAM and PTSD or perceived stress. Interestingly, aromatherapy, one of the CAM methods used in this study, was found to be associated with higher rates of both pregnancy-related anxiety and depression. Social support played a key role in the risk of mental health problems, including pregnancy-related anxiety [Citation16,Citation19].

Depression

Seven studies investigated depression as a primary outcome. The majority of the studies used the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) to screen for depression, using a score of 12 as the cutoff for positive depression screening.

One study that utilized the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) to screen for depression examined 283 patients three to seven months after Hurricane Katrina, and followed them for two years with serial surveys at four different periods of time [Citation15]. Three trajectories for maternal depression among persons exposed to the hurricane were identified: low–low exposure (61%), resilient - low or minimal symptoms over time despite higher exposure (29%), and chronic-high symptoms over time, same exposure as resilient group (10%). Social support was identified as a protective factor. For every additional social support variable, patients were 0.03 times less likely to fall into the chronic-high symptom group (OR = 0.97, 95% CI = 0.95 − 0.99) [Citation15].

Five studies were conducted by one research team evaluating pregnant persons in Louisiana after Hurricane Katrina. In the first study, 402 patients were screened with EPDS. The goal of this study was to determine if the use of CAM had an effect on depression rates among pregnant patients at the time of the storm. This study noted that massage therapy was protective against depression (EPDS <8) [Citation19]. Of those surveyed, 30.7% were found to have depression [Citation19]. With this same population, a second study concluded that depression was associated with poor social support indicators during Hurricane Katrina. Another study utilized the EPDS to screen 292 persons who had been pregnant during or shortly after Hurricane Katrina [Citation20]. Eighteen percent met criteria for depression at two months postpartum. Two or more severe exposures to the storm were associated with an increased risk for depression (RR 1.77, 95% CI 1.08–2.89). Of these, 35% felt their lives were in danger during the storm and 87% were evacuated. Black women were more likely to have perceived or experienced danger. Among the same 292 individuals who gave birth in Baton Rouge or New Orleans after Katrina, the authors then examined depression and infant temperament; 24% screened positive for postpartum depression and 18% were exposed to three or more hurricane-related stressors [Citation17]. Maternal postpartum depression symptoms were significantly correlated with difficult infant temperament at two months (aOR 3.05, 95% CI 1.41–6.63) and twelve months (aOR 3.16, 95% CI 1.22–8.20). In a third study, among 301 studied, the rate of depression was 14.4% using the EPDS [Citation21]. The frequency of low birth weight was higher in those with high hurricane exposure (14.0%) than persons without high hurricane exposure (4.7%) (aOR 3.3; 95% CI: 1.13 − 9.89; p < 0.01). Preterm birth rates were also higher in those with high hurricane exposure (14.0%) than those without high hurricane exposure (6.3%) (aOR: 2.3; 95% CI: 0.82 − 6.38; p > 0.05). However, this study found no difference in the rates of low birth weight or preterm labor in individuals with PTSD or depression compared to those without these conditions [Citation21]. The last study in this series aimed to determine PTSD and depression in this group [Citation21]. The overall rate of depression was 14.4%, and the frequency was higher among those with high hurricane exposure (32.3%) than individuals without high hurricane exposure (12.3%) (aOR 3.3, 95% CI 1.6–7.1). The risk of depression increased with an increasing number of severe hurricane events [Citation18].

A study evaluated maternal depression using the EPDS and the Infant Behavior Questionnaire – Revised (IBQ-R) at six months postpartum in New York after Hurricane Sandy [Citation56]. The author examined 301 mother-child dyads that were exposed or unexposed to Hurricane Sandy during pregnancy. Prenatal maternal depression was associated with greater levels of infant activity, distress, approach, and shorter duration of attention only when also exposed to Sandy in utero [Citation56]. Values from this study were not reported amenably for inclusion in prevalence calculations.

PTSD

Six of the studies examined PTSD as a primary outcome. The Posttraumatic Stress Diagnostics Scale (PDS) was utilized to evaluate 283 persons living in New Orleans three to seven months post-disaster with a scoring of mild = 1–10; moderate = 11–20; moderate-severe = 21–35; severe = 36 and greater [Citation15]. The mean post-traumatic stress scores were mean= 26.99, SD = 17.51, indicating moderate-severe levels of post-traumatic stress severity. Nineteen percent perceived life threat with hurricane exposure, and 31% reported at least one actual life-threatening event (mean = 0.48, SD = 0.92) [Citation15].

The Post-Traumatic Stress Checklist (PCL), a 17-item inventory of PTSD-like symptoms with a cutoff value of 50, was used in a study on the use of CAM and its effect on pregnant persons living in post-disaster New Orleans after Katrina [Citation19]. Nine percent of the 402 patients were found to have PTSD, but the PTSD diagnosis was not significantly associated with CAM use [Citation19].

In another study using the PCL as a screening tool in persons who were pregnant during or shortly after Katrina, the authors found 13% met criteria for PTSD at 2 months postpartum. Exposure to two or more severe experiences during the storm was associated with an increased risk of PTSD (RR 3.68, 95% CI 1.80–7.52) [Citation20].

The PCL-Civilian Version was utilized to screen 292 persons who gave birth in Baton Rouge or New Orleans after Katrina, examining PTSD, depression and infant temperament [Citation17]. Seven percent of these patients screened positive for PTSD, and maternal PTSD symptoms were significantly correlated with infant temperament at 12 months (OR 3.42, 95% CI 1.45–8.08) [Citation17]. The same authors used the PCL-Civilian Version on 301 persons who were pregnant during or immediately after Hurricane Katrina [Citation21]. There were no differences in rates of preterm birth or low birth weight in those with or without PTSD. However, persons who experienced three or more severe hurricane events had a higher risk of preterm delivery or low birth weight. These authors concluded that the rate of PTSD was 4.4% overall; it was higher among individuals with high hurricane exposure (13.8%) than those without high hurricane exposure (1.3%), (aOR 16.8, 95% CI 2.6-106.6) after adjustment for maternal race, age, education, smoking and alcohol use, family income, parity, and other confounders [Citation18,Citation21]. Individuals with four or more severe hurricane events had an increased risk of PTSD (aOR: 31.9; 95% CI 2.2–471.8) [Citation18].

Migration & displacement

The United Nations estimated that in 2019, there are approximately 272 million international migrants, in addition to hundreds of millions of internal migrants, globally, seeking better opportunities for education, employment, health, or security and experiencing more acute drivers for migration, such as natural disasters, violence, and conflict [Citation45]. Determinants of prenatal mental disorders among these individuals are complex and include economic, psychosocial, obstetric, migration and health systems factors [Citation22,Citation23]. Four studies were reviewed on the relationship between political disasters and maternal mental health: three on depression, two on PTSD, and one on anxiety [Citation22–25].

Depression

A systematic review of 40 studies, comprising 19,349 individuals, including 7895 migrant persons with the mean age range of 24 to 33 years, primarily focused on the rate of postpartum depression among migrants [Citation22]. These persons originated from middle-to-high income countries and resettled in North America, Europe, or Australasia. The pooled prevalence of depression across studies was determined using standardized and comparable cut‐off scores on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES‐D), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI‐II) and Postpartum Depression Screening Scale (PDS). It further classified the positive screening by any depressive disorder defined as EPDS ≥10, CES‐D ≥ 16, BDI‐II ≥14 or PDSS ≥60, and major depressive disorder, defined as EPDS ≥13, CES‐D ≥ 24, BDI‐II ≥20 or PDSS ≥80. The pooled prevalence of any depressive disorder across 16 studies (3,492 participants) was 31.4% (95% CI 23.2–40.2%, p = .00, I2 96.4%) and that of major depressive disorder across 17 studies (3186 participants) was 17.3% (95% CI 12.4–22.8%, p = .00, I2 92.5%). Importantly, the rates of depressive disorders did not differ significantly according to the screening test used, study design, pregnancy status, type of migrant, or region [Citation22].

A comparison of recent newcomers to Canada (within 5 years) showed that newcomers, when compared to those Canadian-born, had a significant increase in positive screening for postpartum depression [Citation23]. Overall, 35% of immigrants, 31% of asylum seekers, and 26% of refugees compared to 8% control population had EPDS> =10 (p = .0008) [Citation23]. All groups of newcomers had lower social support as measured by Personal Resource Questionnaire [Citation23]. These findings were similar to a study of 12 Syrian refugees during a focus group [Citation23]. More than half (7/12) of these refugees screened positive for possible depression (EPDS ≥ 10) [Citation23].

PTSD

A case-control study of newborns to pregnant persons diagnosed with PTSD in the Northern district of Swat in Pakistan, who were internally displaced during the armed conflict between Taliban and Security forces in 2008, showed that PTSD was independently associated with low birth weight (LBW) [Citation25]. In this study, those with known mental health problems or serious medical conditions were excluded. Those with known cervical insufficiency, twin gestations, or medically indicated induced labor and newborns with recognizable congenital anomalies were also excluded. PTSD was diagnosed through the MINI Neuropsychiatric Interview 5.0, which has been shown to be a valid and reliable diagnostic tool in pregnant persons and meets the DSM-V diagnostic criteria. Factors significantly associated with LBW included <5 years of paternal schooling (48% versus 37%, OR 1.58, 95% CI 1.08–2.30), and PTSD (31.6% versus 5.8%, OR 7.52, 95% CI 4.02–14.07). PTSD was six times more likely to cause LBW independent of other risk factors [Citation25].

Maternal and neonatal outcomes

In addition to maternal mental health morbidity, many of the papers also commented on other maternal and neonatal pregnancy-related and unrelated outcomes. These outcomes are summarized in . Common findings included preterm birth [Citation17], high rates of cesarean delivery [Citation29,Citation38], higher rates of alcohol abuse in the antenatal and postpartum periods [Citation34], and low birth weight and difficult infant temperament in those with maternal mental health disorders [Citation17,Citation34]. The association of alcohol abuse and preterm birth with depression, anxiety and PTSD in subjects exposed to natural disasters is unclear and further investigation is warranted. The high rates of cesarean delivery (67.8%) [Citation29,Citation38], as well as the moderate-severe psychological impact of these disasters on patients (50.2%) [Citation29,Citation30,Citation55] require the immediate attention of the obstetrical community.

Limitations

The main limitation of this review was the small number of articles that met the inclusion criteria. Therefore, all studies regardless of quality and rating were included. The other limitation was that although hurricanes, earthquakes, displacement and pandemics are types of natural disasters, the pathophysiology behind the adverse pregnancy outcomes is likely to be different in each of these sub-categories. Nevertheless, the focus of this review is to emphasize the emotional and psychological distress that follows exposure to such catastrophic events.

Psychopathology, such as major depression or PTSD, meet the criteria for a chronic condition (compared to adjustment disorder or acute stress disorder) [Citation57]. While certain disasters last longer, the diagnosis of psychopathology is made by patient’s symptoms and the duration of those symptoms. The studies presented here point to higher detection rates of psychopathology when studied in the context of a disaster, yet the final diagnosis based on duration of symptoms is lacking.

Comparison to existing literature

To date, this is the first systematic review to examine the prevalence of maternal anxiety, depression and PTSD following the different types of natural disasters mentioned in this paper. Our review adds to the literature by comprehensively describing the prevalence of the disease, potential risk factors, and suggested interventions to prevent worsening disease. Above all, our review brings the discussion of maternal mental health disease to the forefront of the academic obstetrical community during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusion and implications

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommend that obstetrical care providers screen patients at least once during the perinatal period for depression and anxiety symptoms. It is recommended that all such providers complete a full assessment of mood and emotional well-being during the postpartum visit for each patient [Citation1]. When indicated, obstetrical care providers should initiate medical therapy and take an active role in both the treatment and referral of patients to appropriate behavioral health resources [Citation1].

As obstetricians, it is our role to identify, treat and provide appropriate referrals and follow up for patients suffering from mental health conditions in order to provide comprehensive obstetrical care, and prevent both pregnancy-related and unrelated sequelae of mental health morbidities. Obstetrical providers should be familiar with the suggested interventions to address those that have been exposed to natural disasters ().

Table 4. Protective Factors.

Our review illuminates the elevated rates of anxiety, depression and PTSD in the antepartum and postpartum periods among pregnant persons exposed to natural disasters. In the context of the current global pandemic of COVID-19, these rates are undoubtably high. It is critical that obstetrician-gynecologists recognize that these patients are in need of closer attention and greater psychosocial support as they are living through challenging times of natural disasters. It is urgent that we adopt a gender and racial equity lens to study the current COVID-19 pandemic and its effects, including the policies and actions that are put into place at the global, national, and local levels. This may be especially important in disadvantaged populations and resource-poor communities, where pregnant and birthing persons are especially vulnerable [Citation46,Citation58].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s). No external funding was used for this review.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Committee opinion no. 757. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2018;132(5):e208–e212.

- Lewis Johnson T, Clare C, Johnson J, et al. Preventing perinatal depression now: a call to action. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2020;29(9):1143–1147.

- Fawcett EJ, Fairbrother N, Cox ML, et al. The prevalence of anxiety disorders during pregnancy and the postpartum period: a multivariate bayesian Meta-Analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80(4):18r12527.

- Ukatu N, Clare C, Brulja M. Postpartum depression screening tools: a review. Psychosomatics. 2018;59(3):211–219.

- Owora A, Carabin H, Reese J, et al. Diagnostic performance of major depression disorder case-finding instruments used among mothers of young children in the United States: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2016;201:185–193.

- Rogal S, Poschman K, Belanger K, et al. Effects of posttraumatic stress disorder on pregnancy outcomes. J Affect Disord. 2007;102(1-3):137–143.

- Recommendation: Perinatal Depression: Preventive Interventions | United States Preventive Services Taskforce. Uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/perinatal-depression-preventive-interventions. Published 2020.

- Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the national comorbidity survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52(12):1048–1060.

- Norris F, Friedman M, Watson P, et al. 60,000 Disaster victims speak: part I. An empirical review of the empirical literature, 1981–2001. Psychiatry. 2002;65(3):207–239.

- Neria Y, Nandi A, Galea S. Post-traumatic stress disorder following disasters: a systematic review. Psychol Med. 2008;38(4):467–480.

- Goenjian AK, Steinberg AM, Najarian LM, et al. Prospective study of posttraumatic stress, anxiety, and depressive reactions after earthquake and political violence. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(6):911–916.

- Tang B, Liu X, Liu Y, et al. A meta-analysis of risk factors for depression in adults and children after natural disasters. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):623.

- Prisma-statement.org. http://www.prisma-statement.org/documents/PRISMA-P-checklist.pdf. Published 2020.

- Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies. Effective Public Healthcare Panacea Project. https://www.ephpp.ca/quality-assessment-tool-for-quantitative-studies/?doing_wp_cron=1601530463.1595399379730224609375. Published 2020.

- Lai BS, Tiwari A, Beaulieu BA, et al. Hurricane katrina: maternal depression trajectories and child outcomes. Curr Psychol. 2015;34(3):515–523.

- Giarratano GP, Barcelona V, Savage J, et al. Mental health and worries of pregnant women living through disaster recovery. Health Care Women Int. 2019;40(3):259–277.

- Tees MT, Harville EW, Xiong X, et al. Hurricane katrina-related maternal stress, maternal mental health, and early infant temperament. Matern Child Health J. 2010;14(4):511–518.

- Xiong X, Harville EW, Mattison DR, et al. Hurricane Katrina experience and the risk of post-traumatic stress disorder and depression among pregnant women. Am J Disaster Med. 2010; 5(3):181–187.

- Barcelona de Mendoza V, Harville E, Savage J, et al. Association of complementary and alternative therapies with mental health outcomes in pregnant women living in a postdisaster recovery environment. J Holist Nurs. 2016;34(3):259–270.

- Harville EW, Xiong X, Pridjian G, et al. Postpartum mental health after hurricane Katrina: a cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009;9(1):21.

- Xiong XU, Harville EW, Buekens P, et al. Exposure to hurricane Katrina, post-traumatic stress disorder and birth outcomes. Am J Med Sci. 2008;336(2):111–115.

- Fellmeth G, Fazel M, Plugge E. Migration and perinatal mental health in women from low- and Middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG. 2017;124(5):742–752.

- Ahmed A, Bowen A, Feng CX. Maternal depression in syrian refugee women recently moved to Canada: a preliminary study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):240. ul

- Stewart DE, Gagnon A, Saucier J-F, et al. Postpartum depression symptoms in newcomers. Can J Psychiatry. 2008; 53(2):121–124.

- Rashid HU, Khan MN, Imtiaz A, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder and association with low birth weight in displaced population following conflict in malakand division, Pakistan: a case control study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020; 20(1):166.

- Karaçam Z, Çoban A, Akbaş B, et al. Status of postpartum depression in Turkey: a meta-analysis. Health Care Women Int. 2018;39(7):821–841.

- Durankuş F, Aksu E. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on anxiety and depressive symptoms in pregnant women: a preliminary study. J Maternal-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022;35(2):205–211.

- Lanes A, Kuk JL, Tamim H. Prevalence and characteristics of postpartum depression symptomatology among Canadian women: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):302.

- Saccone G, Florio A, Aiello F, et al. Psychological impact of coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnant women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223(2):293–295.

- Davenport M, Meyer S, Meah V, et al. Moms are not OK: COVID-19 and maternal mental health. Front Glob Womens Health. 2020;1:1.

- Arach AAO, Nakasujja N, Nankabirwa V, et al. Perinatal death triples the prevalence of postpartum depression among women in Northern Uganda: a community-based cross-sectional study. Plos One. 2020;15(10):e0240409.

- Natamba B, Achan J, Arbach A, et al. Reliability and validity of the center for epidemiologic studies-depression scale in screening for depression among HIV-infected and -uninfected pregnant women attending antenatal services in Northern Uganda: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14(1):303.

- Sawyer A, Ayers S, Smith H. Pre- and postnatal psychological wellbeing in Africa: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2010;123(1-3):17–29.

- Nöthling J, Martin C, Laughton B, et al. Maternal post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and alcohol dependence and child behaviour outcomes in mother–child dyads infected with HIV: a longitudinal study. BMJ Open. 2013;3(12):e003638.

- Kang YT, Yao Y, Dou J, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of maternal anxiety in late pregnancy in China. IJERPH. 2016;13(5):468.

- Lee D, Sahota D, Leung T, et al. Psychological responses of pregnant women to an infectious outbreak: a case-control study of the 2003 SARS outbreak in Hong Kong. J Psychosom Res. 2006;61(5):707–713.

- Tokumitsu K, Sugawara N, Maruo K, et al. Prevalence of perinatal depression among Japanese women: a meta-analysis. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2020;19(1):41.

- Hibino Y, Takaki J, Kambayashi Y, et al. Health impact of disaster‐related stress on pregnant women living in the affected area of the Noto peninsula earthquake in Japan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009;63(1):107–115. Feb

- Lee D, Yip A, Chiu H, et al. A psychiatric epidemiological study of postpartum Chinese women. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(2):220–226.

- Qu Z, Wang X, Tian D, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and depression among new mothers at 8 months later of the 2008 Sichuan earthquake in China. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2012;15(1):49–55. Feb 1

- Qu Z, Tian D, Zhang Q, et al. The impact of the catastrophic earthquake in China’s Sichuan province on the mental health of pregnant women. J Affect Disord. 2012;136(1-2):117–123.

- Dekel S, Stuebe C, Dishy G. Childbirth induced posttraumatic stress syndrome: a systematic review of prevalence and risk factors. Front Psychol. 2017;8:560.

- O'Hara M, Swain AM. Rates and risk of postpartum depression—a meta-analysis. Int Rev Psychiatry. 1996;8(1):37–54.

- Rahman A, Iqbal Z, Harrington R. Life events, social support and depression in childbirth: perspectives from a rural community in the developing world. Psychol Med. 2003;33(7):1161–1167.

- Nations U. World Migration Report 2020. United Nations; 2019.

- Gausman J, Langer A. Sex and gender disparities in the COVID-19 pandemic. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2020;29(4):465–466.

- Ford E, Shakespeare J, Elias F, et al. Recognition and management of perinatal depression and anxiety by general practitioners: a systematic review. Fam Pract. 2017;34(1):11–19.

- Fairbrother N, Janssen P, Antony MM, et al. Perinatal anxiety disorder prevalence and incidence. J Affect Disord. 2016;200:148–155.

- Tan CH, Denny CH, Cheal NE, et al. Alcohol use and binge drinking among women of childbearing age—United States, 2011-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(37):1042–1046.

- Martin JA. MPH. Preterm Births United States 2007. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). January 14, 2011.

- Glover V. Prenatal stress and its effects on the fetus and the child: possible underlying biological mechanisms. Adv Neurobiol. 2015;10:269–283.

- Carnegie R, Araya R, Ben-Shlomo Y, et al. Cortisol awakening response and subsequent depression: prospective longitudinal study. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;204(2):137–143.

- O'Donnell KJ, Glover V, Jenkins J, et al. Prenatal maternal mood is associated with altereddiurnal cortisol in adolescence. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38(9):1630–1638.

- Moreno C, Wykes T, Galderisi S, et al. How mental health care should change as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(9):813–824.

- Chang HL, Chang TC, Lin TY, et al. Psychiatric morbidity and pregnancy outcome in a disaster area of Taiwan 921 earthquake. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2002;56(2):139–144.

- Nomura Y, Davey K, Pehme PM, et al. Influence of in utero exposure to maternal depression and natural disaster‐related stress on infant temperament at 6 months: the children of superstorm sandy. Infant Ment Health J. 2019;40(2):204–216.

- Cahill SP, Pontoski K. Post-traumatic stress disorder and acute stress disorder I: their nature and assessment considerations. Psychiatry. 2005;2(4):14–25.

- (a) Engel SM, Berkowitz GS, Wolff MS, et al. Psychological trauma associated with the world trade center attacks and its effect on pregnancy outcome. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2005; 19(5):334–341. (b) Gausman J, Langer A. Sex and gender disparities in the COVID-19 pandemic. J Womens Health. 2020;29(4):465–466.