Abstract

Objective

To identify risk factors, maternal and neonatal adverse outcomes related to unintended lower segment uterine extension during cesarean delivery (CD).

Methods

A retrospective cohort analysis in a single, university-affiliated medical center between 1 January 2018 and 31 December 2019. All singleton pregnancies delivered by CD were included. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to identify maternal and obstetrical predictors for uterine extension during CD. For secondary outcomes, we assessed the correlation between uterine extension and any adverse maternal or neonatal outcome. Risk factors were analyzed using ROC statistics to measure their prediction performance for a uterine extension.

Results

Overall, 1746 (19.3%) CDs were performed during the study period. Of them, 121 (6.9%) CDs were complicated by unintended uterine extension. There was no difference in maternal demographics and clinical data stratified by uterine extension at CD. Uterine extensions were significantly more common following induction of labor, intrapartum fever, premature rupture of membranes, a trial of labor after cesarean, advanced gestational age, emergent CD, and in particular CD during the second stage of labor (37.2% vs. 6.5%) and after failed vacuum extraction (6.6% vs. 1.1%), p < .05 for all. The incidence of postpartum hemorrhage and re-laparotomy did not differ between the groups. Most of the extensions were caudal-directed (40.4%), and were closed by a two-layer closure (92%). Mean extension size was 4.5 ± 1.7 cm. Using multivariable analysis, the only factor that remained significant was CD at the second stage of labor (adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 54.2, 95% CI 4.5–648.9, p = .002), with an area under the ROC curve 0.653 (95% CI 0.595–0.712, p < .001). Emergent CD, body mass index, birth weight, failed vacuum attempt, and trial of labor after cesarean were not significant. For secondary outcomes, an unintended uterine extension was associated with longer operation time, higher estimated blood loss, greater pre- to post-CD hemoglobin difference, increased blood products transfusion, puerperal fever, and longer hospital stay. No clinically significant neonatal adverse outcomes were observed.

Conclusions

In our cohort, second-stage CD was the strongest predictor for an unintended uterine extension. Following uterine extension, women had increased infectious and blood-loss morbidity.

Introduction

Cesarean delivery (CD) is one of the most common surgical procedures performed worldwide with an approximate prevalence of 20–30% of all labors, depending upon geographic region, local medical practice, and various maternal characteristics [Citation1,Citation2]. Compared to vaginal delivery, a CD is associated with increased maternal morbidity, including bleeding, puerperal infection, bladder and bowel injury, thromboembolism, and risk of maternal readmission [Citation3–5]. Neonatal complications are also higher in CD in comparison to vaginal delivery [Citation3]. Multiple variables influence the risk for maternal and neonatal adverse outcomes in CD, such as maternal age, obesity, gestational age at delivery, number of previous CDs, and in-labor CD [Citation3,Citation6].

An unintended uterine incision extension is a defect in the uterine wall occurring outside the line of the originally intended incision that most commonly occurs during fetal extraction. Extensions can potentially cause injury to adjacent organs or blood vessels and increase operative time, therefore, be associated with maternal morbidities, such as puerperal infection and blood loss [Citation7–9].

In this study, we aim to identify modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors for an unintended uterine hysterotomy extension at the time of CD and evaluate the associated adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes. Awareness of such risk factors might assist in preventing modifiable factors and hence decrease complication rate.

Materials and methods

A retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data on all singleton pregnancies delivered by CD between 1 January 2018 and 31 December 2019 at a single, university-affiliated medical center. Cases with missing surgical reports or delivery outcomes were excluded. The study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board Committee (HYMC-20-0057). Informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study. Our primary outcome was to identify risk factors for an unintended uterine extension. For secondary outcomes, we assessed maternal and neonatal outcomes and compared them between the study group (CDs complicated by unintended uterine extension) and the control group (all other CDs).

The study cohort was identified using our computerized database. Women were included using ICD-9 code of CD (74.1). Both scheduled and emergent CDs were included. Our electronic medical report system was customized on 1 January 2018, to include a detailed report on every CD performed. The report is filled prospectively by the attending surgeon immediately after delivery and includes all steps of the operation and any maternal or neonatal complications. Each report includes a check box for any unintended uterine extension with available free text for elaboration. An unintended uterine extension is defined as any accidental elongation of the original uterine incision.

Maternal demographics, general and obstetrical history, delivery data, and maternal and neonatal short-term delivery outcomes were retrieved from the comprehensive computerized database. Gestational diabetes mellitus was defined according to a pathological oral glucose tolerance test. Hypertensive disorder was defined as any gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, or HELLP syndrome. By convention, for every woman undergoing CD, blood is drawn for CBC before and 4–6 h after delivery. Hemoglobin difference was calculated as the difference between them. Estimated blood loss during CD refers to the amount of blood loss estimated by the attending surgeon at the end of the operation.

We used univariate analysis to identify maternal characteristics associated with a uterine extension. Mann–Whitney’s test was used for comparing continuous variables, and the chi-squared test was used for categorical data, augmented by the Fisher exact test if needed. All reported p values were two-sided and the level of p < .05 was considered statistically significant. Parameters with statistical significance in the univariate analysis, or those with potential clinical impact according to literature or experience, were examined via regression analysis: previous CD, body mass index (BMI), gestational age at delivery, induction of labor, regional anesthesia, rupture of membranes, intrapartum fever, a trial of labor after cesarean, failed attempt of vacuum extraction, emergent CD, operation during the second stage of labor and birth weight. Area under the receiver operating characteristics curve (AUC-ROC) statistics was used to evaluate the prediction performance of statistically significant variables. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 21.0 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Overall, 9068 women delivered during the study period. Of them, 204 carried multiple pregnancies and the rest were singleton. Out of all deliveries, 1746 (19.3%) were live birth CDs. A total of 121 (6.9%) cases of uterine extension were identified. Maternal demographics and clinical data stratified by uterine extension at CD are presented in . There was no difference in maternal age, BMI, maternal comorbidities, glucose profile, or rate of pregnancy hypertensive disorders between study and control groups.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical data of study cohort stratified by uterine extension.

Parturients at their first delivery (49.6% vs. 30.8%) and first CD (68.6% vs. 51.3%) were at higher risk for uterine extension during CD (with vs. without extension, p < .001 for all, ). Also, unintended uterine extension was more common following induction of labor (36.4% vs. 15.8%); intrapartum fever (6.6% vs. 1.5%); premature rupture of membranes (15.7% vs. 8.2%); trial of labor after cesarean (57.6% vs. 19.7%); higher gestational age at delivery (39.4 vs. 38.2 gestational weeks); when CD was emergent (88.4% vs. 49.7%) and at the second stage of labor (37.2% vs. 6.5%) and after failed vacuum extraction (6.6% vs. 1.1%), extension vs. no extension, p < .05 for all ( and ).

Table 2. Labor and maternal outcome stratified by uterine extension.

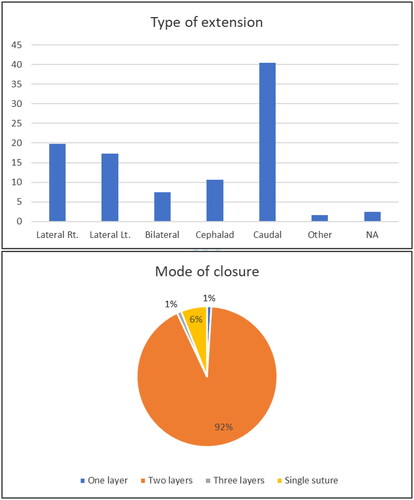

Characteristics of uterine extensions are presented in . Most of the extensions were caudal-directed (40.4%), followed by lateral right (19.8%), lateral left (17.3%), cephalad (10.7%), and bilateral (7.4%). The vast majority of extensions were closed by a two-layer closure. Mean extension size was 4.5 ± 1.7 cm.

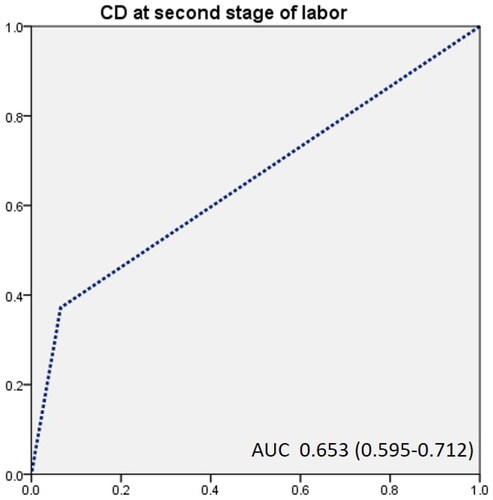

Using multivariable logistic regression analysis, the only factor that remained significantly associated with unintended uterine extension was CD at the second stage of labor (adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 54.2, 95% CI 4.5–648.9, p = .002) with an area under the ROC curve 0.653 (95% CI 0.595–0.712, p < .001) (, ).

Table 3. Regression analysis of risk factors for extension during CD.

Parturients undergoing CD that was complicated by unintended uterine extension had a longer mean operation time (53 vs. 40 min, p < .001); higher estimated blood loss (843 vs. 652 ml, p < .001), and respectively greater hemoglobin level difference before and after CD and a higher rate of blood products transfusion (12.4 vs. 4.2%, p < .001). Postpartum, women with unintended uterine extension had a higher prevalence of puerperal fever (1.7 vs. 0.1%, p < .001) and longer hospitalization duration (5.3 vs. 5.0 days, p < .001) ().

No significant differences were observed regarding neonatal characteristics and outcomes except for higher birthweights and lower mean pH levels for neonates in the study group (7.22 vs. 7.26, p < .001). Nevertheless, the risk for neonatal pH levels lower than 7.1 was similar between groups (). Fetal macrosomia (>4000 g) did not appear to be a risk factor for uterine extension. There were no cases of fetal fractures or bruises.

Table 4. Neonatal outcome stratified by uterine extension.

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the risk factors and outcomes of CDs complicated by unintended uterine extension. Our study results demonstrate: (1) the prevalence of unintended uterine extension during CD was 6.9%; (2) most of the extensions were caudal-directed (40.4%), and were closed by a two-layer closure (92%); (3) most risk factors for uterine extension were factors associated with in-labor CD, including induction of labor, premature rupture of membranes, intrapartum fever, a trial of labor after cesarean, emergent CD, CD at the second stage and following failed attempt of vacuum extraction. Using multivariable logistic regression analysis, the only factor that remained statistically significant was CD at the second stage of labor (aOR 54.2, 95% CI 4.5–648.9, p = .002). No modifiable risk factors were noted in this study; (4) unintended uterine extension was associated mainly with maternal adverse outcomes including higher blood loss, need for blood transfusion, puerperal fever, and longer postoperative admission length. For the neonate, an unintended uterine extension was associated with mildly higher birthweights and lower pH levels, without higher rates of fetal acidemia or fetal macrosomia.

Only a few studies had been published regarding unintended lower uterine segment extension during CD. In our study, 6.9% of CDs were complicated by extensions, like the rate reported in the literature [Citation7,Citation8]. de la Torre et al. [Citation8] conducted a retrospective analysis of all CDs in a single center between 1999 and 2002 and reported 6.8% of unintended extension (186/2811). In agreement with our study, factors that were associated with unintended uterine extension were those associated with in-labor CD: primary CD, chorioamnionitis, cervical dilatation >8 cm, complete effacement, fetal station above +1, and fetal occiput posterior position. Arrest of descent as an indication of CD was found to be an independent risk factor for the occurrence of extensions during CD (odds ratio 2.6, 95% CI 1.5–4.5, p = .001) [Citation8]. Also, similar to our results, when extensions were present, the length of surgery was longer, and estimated blood loss was greater with a higher difference in hematocrit levels measured before and after delivery. Unlike our study, the authors reported similar rates of need for blood transfusion and no increase in febrile morbidity or maternal hospital length admission following CD complicated by uterine extension. It is important to note that their study included mainly Hispanic population (70%) and although there was a greater hematocrit drop in the extension group, there was no difference in the post-delivery hematocrit level. Finally, the authors concluded that extensions during CD were not associated with maternal morbidity [Citation8]. Patel et al. also evaluated the outcome following CD complicated by unintended uterine extension [Citation7]. The authors conducted a retrospective case-control study that included 126 CDs complicated by extension that were compared to 126 control CDs. CDs were included only if they were primary and at full term. Unlike previous reports and more like our results, women with extensions had higher estimated blood loss and a higher rate of composite maternal morbidity that included blood transfusion, endometritis, or readmission. Additionally, women with extensions had an increased risk of postpartum hemorrhage and were associated with prolonged lengths of hospital stay [Citation7]. Compared to this study, our study included all CDs (primary and non-primary, elective, and emergent) and without restriction to term.

We found that uterine extensions were significantly associated with increased blood loss estimation and need for blood transfusion, which is probably related to the increase in the hysterotomy closure time. Also, both lateral and vertical extensions can involve injury to branches of the uterine arteries that can potentially bleed profoundly until closure.

All studies suggest that second-stage CD is associated with uterine extension. Compared to elective or even CDs performed at the first stage of labor, CD at the second stage of labor is more challenging and demands higher technical skills from the surgeon [Citation10–12]. Extraction of the fetal head, which is sometimes impacted low in the maternal pelvis, requires dislodgement of the fetal head, safely pulling the baby out. At this stage, any erroneous maneuver or hand manipulation might cause an unintended elongation of the original incision. Moreover, CDs performed during the second stage are often emergent, especially if prolonged second stage, following failed attempt of vacuum extraction or accompanied by suspected fetal distress. This by itself may increase the risk of surgeon stress leading to sub-optimal surgical technique [Citation10,Citation11,Citation13,Citation14]. A study by Vitner et al. had shown that the risk for unintentional uterine incision extension during CD in the second stage of labor is almost seven times higher when compared to CD during the first stage of labor [Citation12]. In our study, CD during the second stage of labor was the only independent risk factor for uterine extension with an aOR of 54.2, nearly eight times higher compared to Vitner et al. results. Karavani et al. assessed 397 CDs performed in the second stage of labor with extensions and found that past CD and failed vacuum attempt were independent parameters associated with unintended uterine incision extension [Citation14].

Previous studies had compared different operation techniques as a risk factor for unintended extension rate: sharp vs. blunt technique for uterine opening, transversal (lateral–lateral) vs. cephalad–caudad direction incision expansion. Most studies found that blunt expansion is safer compared to sharp expansion and that cephalad–caudad incision expansion is less associated with uterine extensions [Citation9,Citation15–19]. In our medical center, it is customary to perform low transverse CD for both term and preterm deliveries. The sharp uterine incision is then followed by blunt transverse expansion of the incision. Most studies did not detail the direction of uterine extension. In our study, most of the extensions were vertical (51.1%), mostly caudal-directed, and 44.5% were lateral, mostly (83%) unilateral. One study reported that two-thirds of extensions were lateral, mostly unilateral [Citation14].

Our study demonstrated that CDs complicated by extension were associated with larger babies and a lower pH level at delivery. Most studies did not evaluate neonatal outcomes. However, neonatal birth weight was similarly reported higher in de la Torre study [Citation8]. Patel et al. reported similar neonatal birthweights without differences in neonatal intensive care unit admission between groups [Citation7]. In any case, birthweight did not remain a statistically significant risk factor in our multi-regression analysis.

As no modifiable risk factors for uterine extensions were identified, and given the maternal and neonatal morbidity associated with this issue, efforts should be made to raise awareness for this complication. Other techniques for fetal extraction, especially in the second stage of labor, should be introduced and evaluated. The evidence regarding other methods of fetal extraction is limited and conflicting, including reverse breech extraction [Citation20,Citation21], assisted vaginal pushing of the fetal head by an assistant [Citation22,Citation23], and the “fetal pillow” [Citation24,Citation25]. A 2016 Cochrane review suggested that reversed breech extraction may improve maternal and fetal outcomes, but with limited evidence [Citation26]. Further randomized controlled trials are needed to evaluate the role of these techniques.

Our study has several strengths. First, our data were based on our computerized database which is under constant prospective meticulous review by senior attending physicians. Second, it includes a large number of participants with detailed information on both maternal and neonatal outcomes. Lastly, unlike previous studies, our cohort included all CDs primary and non-primary at all gestational ages in a heterogeneous population of patients.

However, our study is not free of limitations. Our study is restricted due to its retrospective design. We could not evaluate the effect of surgical technique, mode of fetal extraction, or surgeon level of expertise on the prevalence of extensions. Also, only a few neonatal outcomes were assessed in our study.

In conclusion, according to our study, CD performed during the second stage of labor is the most important determinant for an unintended uterine extension. Pros and cons of second-stage CD should be weighted individually, considering its associated morbidity.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK, et al. Births: final data for 2017. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2018;67(8):1–50.

- Boerma T, Ronsmans C, Melesse DY, et al. Global epidemiology of use of and disparities in cesarean sections. Lancet. 2018;392(10155):1341–1348.

- ACOG Committee Opinion No. 761. Cesarean delivery on maternal request; 2023.

- Hammad IA, Chauhan SP, Magann EF, et al. Peripartum complications with cesarean delivery: a review of maternal-fetal medicine units network publications. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014;27(5):463–474.

- Belfort MA, Clark SL, Saade GR, et al. Hospital readmission after delivery: evidence for an increased incidence of non-urogenital infection in the immediate postpartum period. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(1):35.e1–35–e7.

- Pallasmaa N, Ekblad U, Aitokallio-Tallberg A, et al. Cesarean delivery in Finland: maternal complications and obstetric risk factors. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010;89(7):896–902.

- Patel SS, Koelper NC, Srinivas SK, et al. Adverse maternal outcomes associated with uterine extensions at the time of cesarean delivery. Am J Perinatol. 2019;36(8):785–789.

- de la Torre L, González-Quintero VH, Mayor-Lynn K, et al. Significance of accidental extensions in the lower uterine segment during cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(5):e4–e6.

- Asıcıoglu O, Gungorduk K, Asıcıoglu BB, et al. Unintended extension of the lower segment uterine incision at cesarean delivery: a randomized comparison of sharp versus blunt techniques. Am J Perinatol. 2014;31(10):837–844.

- Chopra S, Bagga R, Keepanasseril A, et al. Disengagement of the deeply engaged fetal head during cesarean section in advanced labor: conventional method versus reverse breech extraction. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2009;88(10):1163–1166.

- Pergialiotis V, Vlachos DG, Rodolakis A, et al. First versus second stage C/S maternal and neonatal morbidity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;175:15–24.

- Vitner D, Bleicher I, Levy E, et al. Differences in outcomes between CD in the second versus the first stages of labor. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;32(15):2539–2542.

- Giugale LE, Sakamoto S, Yabes J, et al. Unintended hysterotomy extension during caesarean delivery: risk factors and maternal morbidity. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;38(8):1048–1053.

- Karavani G, Chill HH, Reuveni-Salzman A, et al. Risk factors for uterine incision extension during cesarean delivery. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022;35(11):2156–2161.

- Hameed N, Ali MA. Maternal blood loss by expansion of uterine incision at caesarean section – a comparison between sharp and blunt techniques. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2004;16(3):47–50.

- Cromi A, Ghezzi F, Di Naro E, et al. Blunt expansion of the low transverse uterine incision at cesarean delivery: a randomized comparison of 2 techniques. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(3):292.e1–292.e6.

- Morales A, Reyes O, Cárdenas G. Type of blunt expansion of the low transverse uterine incision during caesarean section and the risk of postoperative complications: a prospective randomized controlled trial. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2019;41(3):306–311.

- Saad AF, Rahman M, Costantine MM, et al. Blunt versus sharp uterine incision expansion during low transverse cesarean delivery: a metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211(6):684.e1–684.e11.

- Xodo S, Saccone G, Cromi A, et al. Cephalad–caudad versus transverse blunt expansion of the low transverse uterine incision during cesarean delivery. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;202:75–80.

- Veisi F, Zangeneh M, Malekkhosravi S, et al. Comparison of “push” and “pull” methods for impacted fetal head extraction during cesarean delivery. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2012;118(1):4–6.

- Fasubaa OB, Ezechi OC, Orji EO, et al. Delivery of the impacted head of the fetus at caesarean section after prolonged obstructed labour: a randomised comparative study of two methods. J Obstet Gynaecol J Inst Obstet Gynaecol. 2002;22:375–378.

- Levy R, Chernomoretz T, Appelman Z, et al. Head pushing versus reverse breech extraction in cases of impacted fetal head during cesarean section. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005;121(1):24–26.

- Manning JB, Tolcher MC, Chandraharan E, et al. Delivery of an impacted fetal head during cesarean: a literature review and proposed management algorithm. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2015;70(11):719–724.

- Safa H, Beckmann M. Comparison of maternal and neonatal outcomes from full-dilatation cesarean deliveries using the fetal pillow or hand-push method. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2016;135(3):281–284.

- Sacre H, Bird A, Clement-Jones M, et al. Effectiveness of the fetal pillow to prevent adverse maternal and fetal outcomes at full dilatation cesarean section in routine practice. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021;100(5):949–954.

- Waterfall H, Grivell RM, Dodd JM. Techniques for assisting difficult delivery at caesarean section. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2016:CD004944.