Abstract

Background

In 2017, China proposed to achieve the goal that 50% of infants aged 0-6 months should be exclusively breastfed by 2025 proposed by the World Health Assembly in 2012. However, delayed onset lactogenesis II has adverse effects on breastfeeding and thus on neonatal health. There has been no meta-analysis of the prevalence and risk factors of delayed onset lactogenesis II among parturient women in China. To provide best practices, updated evidence-based evidence is needed to supplement reviews on this topic.

Objective

The purpose of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to quantitatively analyze the prevalence and risk factors of delayed onset lactogenesis II in China.

Methods

We identified relevant studies by searching literature published prior to October 2022 in PubMed, Web of Science, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, Wanfang, and VIP databases for all available observational studies. Stata 16.0 were used for performing the systematic review and meta-analysis.

Results

The researchers examined data from 14 observational studies involving 17610 females. The prevalence of delayed onset lactogenesis II from these studies was 31% (95% CI = 25.0%–38.0%, p < .001), and the prevalence showed a significant increasing trend in China over the past decade. The frequency of breastfeeding was >2 times per day at 24–48 h after delivery was one protective factor against delayed onset lactogenesis II (OR = 0.41). The significant risk factors for delayed onset lactogenesis II were breastfeeding initiation > 30min after birth (OR = 1.31), maternal age > 35 years (OR = 2.19), primiparous women (OR = 2.38), maternal overweight/obesity (OR = 2.22), cesarean section (OR = 1.33), anxiety (OR = 3.23), depression (OR = 3.21) and gestational hypertension (OR = 3.43).

Conclusions

There is a high incidence of delayed onset lactogenesis II in Chinese parturient women. We identified eight risk factors and one protective factor for DOL II. These findings suggest health care professionals should pay attention to these risk parturients so as to better provide early preventive interventions to increase the breastfeeding rate.

Introduction

The onset of lactogenesis II (OL) defined as the onset of copious milk secretion, which occurs between 36 and 92 h after delivery and is usually measured by the perception of maternal breast hardness, fullness, or leakage of colostrum [Citation1]. The timing of OL is important for the success of breastfeeding and the health of newborns. Women who develop lactation symptoms more than 72 h postpartum are considered to have delayed onset lactogenesis II (DOL II) [Citation2]. DOL II was proved to increase the risk of breast-feeding cessation within 6 months, shorten the duration of breast-feeding, increase the risk of neonatal overweight, and reduce the risk [Citation3,Citation4].

Women and children are the key groups that need to solve health problems in the outline of “Healthy China 2030”, which is related to the implementation of the national health strategy [Citation5]. Breastfeeding is beneficial to maternal and infant health, and has short-term and long-term health benefits for lactating women and infants [Citation6]. Since 2007, more breastfeeding initiatives and interventions have been taken to promote breastfeeding in China. Early skin-to-skin contact significantly improved the rate of exclusively breastfeeding at one or six months of age among neonates [Citation7]. In 2017, China began to implement that newborns and their mothers should keep uninterrupted skin contact for at least 90 min. In recent years, maternity leave has increased from 90 d to 120–180 d in China. However, the exclusive breastfeeding rate of infants under 6 months in China is only 20.8%, which is far below the global target of 50% set by WHO [Citation8]. One reason is that several researchers in China have found an occurrence rate of DOL II between 18% and 39%, higher than in some other countries, and DOL II can lead to chronic supplementation of infant formula and poor exclusive breastfeeding rates [Citation9]. The second reason is that China has one of the highest prevalence of Cesarean section in the world, reaching 60% in some areas of China. Cesarean delivery is an established risk factor for DOL II and is strongly linked with poorer breastfeeding practices [Citation10]. As a simple and convenient early clinical marker, DOL II can help identify women who need additional breastfeeding support or intervention to increase milk production and extend exclusive breastfeeding. Therefore, it is important to explore the prevalence and potential influencing factors of delayed initiation of lactation stage II.

Previous studies have reported a wide range of risk factors, such as cesarean delivery, difficulty positioning the infant at the breast, flat or inverted nipples, and excessive weight gain during pregnancy, have been related to delayed onset lactogenesis II [Citation11,Citation12]. Despite the fact that the estimated prevalence and risk factors of DOL II are widely investigated, these results are still discrepant. Because of the differences in medical practice and local diet, people may not always be able to extend the research results to all people. Therefore, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to reliably estimate the prevalence and risk factors of delayed onset lactogenesis II among Chinese mothers so as to provide better targeted evidence-based recommendations for DOL II.

Materials and methods

Systematic search and strategy

Our meta-analysis followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [Citation13]. A comprehensive search of PubMed, Web of Science, CNKI (China National Knowledge Infrastructure), Wanfang (Chinese), and VIP (Chinese) databases were conducted for studies related to lactation II delay prior to October 2022. The following search terms were used: (“lactation II” OR “lactogenesis stage II” OR “stage II lactogenesis” OR “lactation initiation” OR “lactogenesis II” OR “onset of Lactation” OR “secretory activation”) AND (“factor” OR “risk factor”) AND (“China” OR “Chinese). We limited our language of publications to English and Chinese and searched the reference list to include all relevant research as comprehensively as possible. The study was limited to studies that assessed parturient women in China.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The selected studies were required to meet the following criteria in order to fit the analysis requirements and reduce selection bias. (1) Study population: Chinese women who had delayed onset lactogenesis II. (2) Period: the time range of this research is limited to October 2022. (3) Study type: observational studies with case-control, cross-sectional, or cohort designs. (4) Information: the prevalence or influencing factors of delayed onset lactogenesis II were reported. Articles published in the form of conference abstracts, reviews, narrative reviews, and case reports were excluded.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two researchers extracted data independently, and any disagreement was resolved through discussion with the third researcher. The extracted data were recorded in Microsoft Excel file format, and the following variables were extracted from each eligible research: first author, year of publication, study design, sample size, period, study region, the prevalence of DOL II, and the influencing factors mentioned. If there is missing or unclear data, we requested it by emailing the corresponding author of the article. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) criteria was used to analyze the quality of the included articles [Citation14]. There were three factors of patient selection, group comparability, and outcome assessment. The higher the score, the higher the quality. A score of 7 or more out of 9 indicated a high-quality article.

Outcome measurements

There were two main outcomes. The primary outcome measure of prevalence was the number of women with delayed onset lactogenesis II in the study divided by the total number of women in a study multiplied by 100. To analyze secondary outcomes (factors associated with DOL II), we extracted data on factors found to be associated with DOL II in the literature, such as breastfeeding initiation > 30 min after birth; the frequency of breastfeeding was >2 times per day at 24–48 h after delivery; maternal age > 35 years; primiparous women; maternal overweight/obesity: overweight and obesity defined as BMI of >25 kg/m2 and >30 kg/m2, respectively; cesarean section; anxiety: the scale to assess perinatal anxiety was Self-rating Anxiety Scale(SAS); depression: the scale to assess perinatal depression was Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS); and gestational hypertension.

Statistical analysis

We analyzed the extracted data using STATA statistical software, version 14. Heterogeneity between studies was evaluated using I2 statistic, which shows the percentage of variation across studies. If the data showed low or moderate heterogeneity (I2 < 50%), a fixed-effect model was used; otherwise, a random-effect model was used. Sensitivity analysis was used to analysis the data after sequentially excluding individual studies. Subgroup analysis was carried out when necessary to solve heterogeneity. In addition, Egger’s statistical test was used to analyze whether publication bias had statistical significance.

Results

Search results

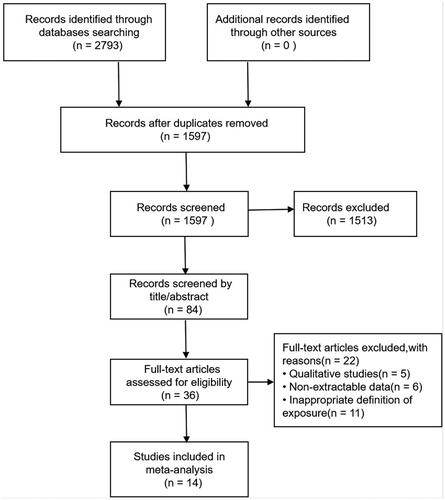

Our initial searches identified 2793 records and removed 1196 duplicate records. After title and abstract screening, 36 studies were found eligible for full-text screening. A total of 14 studies [Citation15–28] were finally qualified, with 17,610 perinatal Chinese women in China. Details of the study selection process are shown in . shows the detailed characteristics of the 14 selected studies. In the quality assessment scale, the quality of all included studies ranged from 6 to 9, indicating that the quality of the studies was fair.

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies.

Meta analysis results

Pooled prevalence rates of DOL II

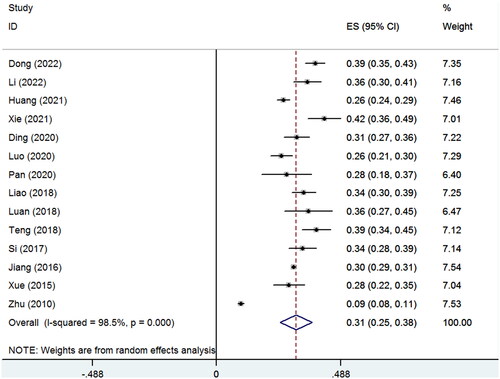

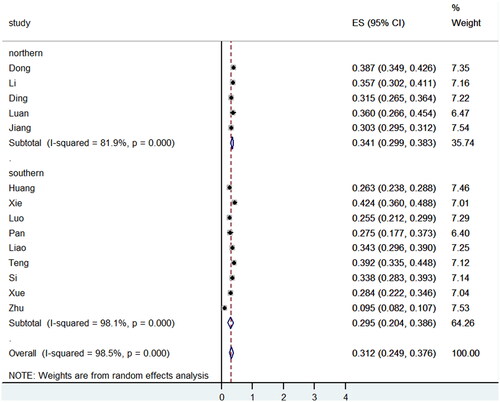

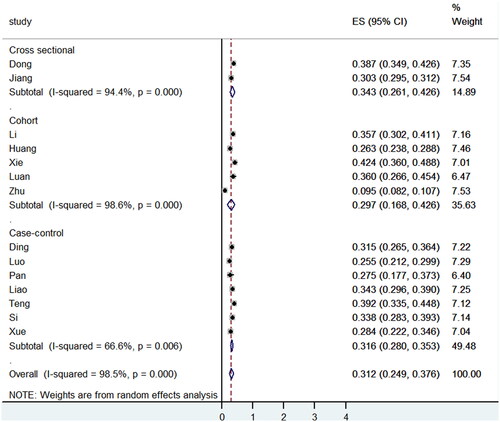

The random effects model showed that the pooled prevalence of DOL II was 31% (95% CI = 25.0%–38.0%, p < .001). The data presented significant heterogeneity with a high I2 value of 98.5% (). Subgroup analyses were performed according to the China region and study type (). Regionally, the pooled prevalence in southern China (29.5%, 95% CI: 20.4–38.6%) was lower than that of northern China (34.1.0%, 95% CI: 19.9–38.3%) in China. The prevalence of DOL II among the study types of cross-sectional, cohort, and case-control, the prevalence of DOL II was similar (34.3, 29.7 and 31.6%, respectively). Sensitivity analysis was used to exclude the studies one by one, and there was no significant change in the prevalence of delayed initiation of lactation stage II. Egger’s test confirmed that there was no significant risk of bias (p = .322).

We systematically reviewed the important risk factors for DOL II and categorized them into two categories: (1) Maternal-related factors; (2) Infant-related factors. describes the detailed information.

Table 2. Pooled influencing factors of delayed onset lactogenesis II.

Infant-related factors

Three studies found that breastfeeding initiation > 30 min after birth carried a higher risk of DOL II (OR = 1.31, 95% CI: 1.07–1.59, p = .009). However, significant heterogeneity was present(p < .001, I2 = 92.5%). Sensitivity analysis showed that Jiang was the main source of heterogeneity. After removing Jiang from the meta-analysis, Breastfeeding initiation > 30 min after birth was still a significant risk factor (OR = 1.10, 95% CI: 1.05–1.15, p < .001), while the remaining two studies were homogeneous (p = .581, I2 = 0%). Two studies found the frequency of breastfeeding was >2 times per day at 24–48 h after delivery as a protective factor associated with DOL II (OR = 0.41, 95% CI: 0.25–0.66, p < .001).

Maternal-related factors

Six studies reported maternal age > 35 years as a risk factor associated with delayed onset lactogenesis II (OR = 2.19, 95% CI: 1.81–2.65, p < .001). Primiparous women was mentioned as a risk factor by seven studies (OR = 2.38, 95% CI:1.99–2.86, p < .001). Five studies found associations with maternal overweight/obesity (OR = 2.22, 95% CI: 1.28–3.33, p = .004). Anxiety (OR = 3.23, 95% CI: 2.17–4.82, p = .000) and depression (OR = 3.21, 95% CI: 2.19–4.70, p < .001) in the perinatal period were identified by three studies as potential risk factors for DOL II. Cesarean section was also identified as a risk factor for DOL II (OR = 1.33, 95% CI: 1.21–1.47, p < .001). Four studies revealed an association between gestational hypertension and DOL II (OR = 3.43, 95% CI: 2.54–4.61, p < .001).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive review of the evidence on this condition in China. We found that the pooled estimate of delayed onset lactogenesis II prevalence among subjects in China was 31% (95% CI: 0.25–0.38). Our estimated prevalence was similar to a study in the United States [Citation29] (34%), and higher than that reported for women in Brazil [Citation12] (19%). As the largest developing country, China is experiencing an emerging epidemic of delayed onset lactogenesis II, which might be related to the recently issued “three-child” policy. Our review revealed that the prevalence of delayed onset lactogenesis II among Chinese mothers has obviously increased over the past decade (from 9.0 to 39.0%) in China. As a result, the exclusive breastfeeding rate of infants in China is only 29% at 6 months, far lower than the World Health Assembly’s goal [Citation30] to “increase exclusive breastfeeding rate in the first 6 months to at least 50% by 2025”. Our results of potential influencing factors related to delayed initiation of lactation stage II indicated a statistically significant correlation with nine factors: breastfeeding initiation > 30 min after birth, the frequency of breastfeeding was >2 times per day at 24–48 h after delivery, maternal age > 35 years, primiparous women, maternal overweight/obesity, cesarean section, anxiety, depression, and gestational hypertension.

Breastfeeding initiation > 30 min after birth was a risk factor, and the frequency of breastfeeding was >2 times per day at 24–48 h was one protective factor against DOL II. This finding was consistent with the results of a review [Citation31]. After the placenta is delivered, the level of progesterone in the maternal women drops rapidly, triggering secretion activation. With the onset of secretory activity, women usually experience a feeling of breast fullness for the first few days. However, milk synthesis will decline without an infant or breast pump to draw out the milk [Citation32]. Sucking is the main stimulus of prolactin secretion after delivery, and the sucking reflex of newborns is strongest within 30 min after delivery. Therefore, the early sucking of newborns is responsible for the establishment and maintenance of the lactation reflex of the parturient. Matthews [Citation33] mentioned that proper feeding position, timely and effective sucking are necessary conditions for successful breastfeeding. However, about 60% of newborns in the world fail to be breastfed within one hour of birth, with one of the lowest rates (32%) recorded in China [Citation34]. Thus, it is critical to encourage Chinese mothers to breastfeed early and frequently. Meanwhile, medical staff could provide education and support on breastfeeding and infant feeding clues for pregnant women, and enhance their confidence in breastfeeding.

The results of this review indicated that maternal overweight/obesity was also a risk factor for delayed onset lactogenesis II. Rapid industrialization and urbanization in China are likely to lead to accelerated changes in lifestyle and nutrition, which may increase the proportion of obesity and overweight Chinese women. A study of primiparous women in California showed that 45% of overweight women and 54% of women with obesity had delayed lactogenesis II [Citation35]. The possible reason is that obesity could increase insulin resistance, and insulin resistance may delay the time it takes to reach the concentration necessary for the onset of mature milk production [Citation36]. Additionally, obese women may have greater mechanical difficulties in latching on and correctly positioning their feeding positions [Citation37]. A systematic review by De Bortoli and Amir found that gestational hypertension may lead to delayed lactogenesis II and insufficient lactation [Citation38]. Our review also found that gestational hypertension was a risk factor related to DOL II. The possible role of hypertension in lactation disorders is not fully understood. However, placental dysfunction is a characteristic feature of preeclampsia and is often considered an underlying cause of delayed onset lactogenesis II. It is theoretically possible that placental hormones (e.g. progesterone) that affect the proliferation during pregnancy are compromised in preeclampsia [Citation39]. This suggests that healthcare professionals should pay more attention to maternal lifestyle and help them successfully establish breastfeeding before discharge from the hospital.

Primiparous women and maternal age over 35 are risk factors for delayed lactogenesis II, which was consistent with previous studies in different countries [Citation40]. It may be related to the incorrect breastfeeding posture of primiparas, the psychological influence of childbirth fear, and too long labor process. With the increase of employment opportunities for Chinese women, more and more women join the workforce with strong career ambition, which lead to an increasing proportion of advanced maternal age among pregnant women [Citation41]. But the parturients over 35 years old are high-risk pregnant woman, mammary tissue begins to regress after age 35, and metabolism may be more stressed with aging gain. In addition, our review indicated that delayed onset lactogenesis II was more likely to occur in women who delivered by cesarean section compared to women who delivered vaginally. Further analysis showed a significantly higher incidence of DOL II in women who underwent emergency cesarean section [Citation42]. This may be related to increased maternal and fetal stress levels due to emergency cesarean section or prolonged labor [Citation43]. However, we did not distinguish between emergency and scheduled cesarean sections due to insufficient data, so future research is warranted to clarify the relationship.

Our review showed that anxiety and depression present during delivery may negatively affect lactogenesis, consistent with the findings of previous studies [Citation12]. Chronic physiological or psychological stress may inhibit oxytocin and the milk ejection reflex, also negatively affecting lactation [Citation44]. At the same time, maternal depression and anxiety may lead to poor sleep, which can further dampen the oxytocine system and the milk ejection reflex. Casey found that delayed onset lactogenesis II was associated with less efficient sleep in the third trimester and irregular nighttime sleep schedules [Citation29]. Considering its negative effect on maternal and infant health, medical staff should give psychological guidance to puerpera in time to reduce perinatal anxiety and depression symptoms. Furthermore, a good level of family support, especially the emotional and behavioral support and encouragement of infants’ fathers, can greatly enhance mothers’ mood.

Limitation

In spite of the strengths of this systematic review, our review has some limitations. The literature included in this review has high heterogeneity, which may be different from the research object, differences in the study area, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and research methods are related. In addition, there are few studies on DOL II in China at present, and further studies are needed to verify the results.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis provides the first quantitative synthesis of the prevalence and influencing factors for delayed onset lactogenesis II in China, further expanding our knowledge in this topic area. So that health care professionals could better identify women at risk during pregnancy or early postpartum and give them effective guidance, like timely breastfeeding management, flagging and intervening for psychological concerns early, providing anticipatory guidance on getting enough sleep. Considering the huge population of China, even modest progress in the preventive management of DOL II could significantly improve good breastfeeding levels.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, yiqun miao, yanan li and yuanyuan zhang; Data curation, shuliang zhao; Formal analysis, yiqun miao and shuliang zhao; Investigation, yiqun miao, huimin jiang and yanan li; Methodology, yiqun miao, huimin jiang and wenwen liu; Project administration, wenwen liu; Software, huimin jiang and yanan li; Supervision, aihua wang and yuanyuan zhang; Validation, shuliang zhao and aihua wang; Visualization, aihua wang; Writing-original draft, yiqun miao and shuliang zhao; Writing-review & editing, aihua wang and yuanyuan zhang.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

No additional data available

Additional information

Funding

References

- Neville MC, Morton J, Umemura S. Lactogenesis. The transition from pregnancy to lactation. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2001;48(1):35–52.

- Chapman DJ, Pérez-Escamilla R. Maternal perception of the onset of lactation is a valid, public health indicator of lactogenesis stage II. J Nutr. 2000;130(12):2972–2980.

- Farah E, Barger MK, Klima C, et al. Impaired lactation: review of delayed lactogenesis and insufficient lactation. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2021;66(5):631–640.

- Lavagno C, Camozzi P, Renzi S, et al. Breastfeeding-Associated hypernatremia: a systematic review of the literature. J Hum Lact. 2016;32(1):67–74.

- Tan X, Zhang Y, Shao H. Healthy China 2030, a breakthrough for improving health. Glob Health Promot. 2019;26(4):96–99.

- Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJ, et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet. 2016;387(10017):475–490.

- Huang C, Hu L, Wang Y, et al. Effectiveness of early essential newborn care on breastfeeding and maternal outcomes: a nonrandomized controlled study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22(1):707.

- Shi H, Yang Y, Yin X, et al. Determinants of exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months in China: a cross-sectional study. Int Breastfeed J. 2021;16(1):40.

- Tatum M. China’s three-child policy. Lancet. 2021;397(10291):2238.

- İsik Y, Dag ZO, Tulmac OB, et al. Early postpartum lactation effects of cesarean and vaginal birth. Ginekol Pol. 2016;87(6):426–430.

- Nommsen-Rivers LA. Does insulin explain the relation between maternal obesity and poor lactation outcomes? An overview of the literature. Adv Nutr. 2016;7(2):407–414.

- Rocha BO, Machado MP, Bastos LL, et al. Risk factors for delayed onset of lactogenesis II among primiparous mothers from a Brazilian baby-friendly hospital. J Hum Lact. 2020;36(1):146–156.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLOS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

- Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(9):603–605.

- Jiang S, Duan YF, Pang XH, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for delayed onset lactation in Chinese lactating Mowen in 2013. Chin J Prev Med. 2016;50(12):1061–1066.

- Xiao XX, Zhao MH. Current status of delayed onset of lactogenesis II of high-risk pregnant women in maternal intensive care unit and its influence factors: a 229-case study. J Nurs. 2021;28(07):49–53.

- Ding PP, Zhao M, Zhang FY, et al. Nutrients intake in the third trimester and associated factors of delayed onset of lactogenesis II in maternal women. Chinese Gen Pract. 2020;23(05):534–539. In Chinese)

- Teng ZN, Tan XX, Zhou YZ, et al. Status of delayed onset of lactogenesis and its related factors among women of advanced reproductive age. J Nurs Sci. 2018;33(10):33–35.

- Xue XC, Xu Q, Liu L, et al. Dietary intake and factors influencing delayed onset of lactation among postpartum women in guangzhou. South China J Prev Med. 2015;41(03):218–223.

- Dong FX, Li L, Zhu KH, et al. Analysis of current status and influencing factors of lactation initiation delay in women with vaginal delivery. Chin J Prac Nurs. 2022;38(19):1496–1502.

- Li JJ, Yu XR, Wang YF, et al. The influencing factors of delayed onset of lactogenesis II in preterm parturient women separated from their infants]. Chin J Nurs Educ. 2022;19(04):368–373.

- Pan HY, Zhao X, Li HX. Influencing factors of delayed lactation initiation in parturient after cesarean section. Qilu Nurs J. 2020;26(18):86–88.

- Liao Y, Xu MY. Factor analysis of delayed lactation onset in gestational diabetes patients. Chin Nurs Res. 2018;32(23):3785–3788.

- Si ML, Gu P, Zhang AX, et al. Risk factors of delayed onset of lactogenesis among puerpera with gestational diabetes mellitus. J Nurs Sci. 2017;32(08):19–21.

- Luo FJ, Bao NZ, Li SH. Establishment and validation of a predictive model for the risk of delayed lactation initiation in pregnant women with gestational diabetes mellitus. J Clin Pathol Res. 2020;40(06):1394–1400.

- Huang HL, Gu XQ, Feng HW. Status and influencing factors of delayed initiation of lactation phase II in parturients in baoshan district, shanghai. South China J Prev Med. 2021;47(12):1493–1496.

- Zhu P, Tao FB, Jiang JM, et al. Impact of stressful life event, weight gain during pregnancy and mode of delivery on the delayed onset of lactation in primiparas. Wei Sheng Yan Jiu. 2010;39(4):478–482.

- Luan DD, Yu XR, Lin XY. Correlation between the onset time of lactation period II and lactation yield of the early stage after delivery preterm’s mothers. Chin J Mod Nurs. 2018;24(08):874–879.

- Casey T, Sun H, Burgess HJ, et al. Delayed lactogenesis II is associated with lower sleep efficiency and greater variation in nightly sleep duration in the third trimester. J Hum Lact. 2019;35(4):713–724.

- Kang L, Liang J, He C, et al. Breastfeeding practice in China from 2013 to 2018: a study from a national dynamic follow-up surveillance. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):329.

- Tao XY, Huang K, Yan SQ, et al. Pre-pregnancy BMI, gestational weight gain and breast-feeding: a cohort study in China. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20(6):1001–1008.

- Truchet S, Honvo-Houéto E. Physiology of milk secretion. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;31(4):367–384.

- Matthews MK. Developing an instrument to assess infant breastfeeding behaviour in the early neonatal period. Midwifery. 1988;4(4):154–165.

- Wu W, Zhang J, Silva Zolezzi I, et al. Factors influencing breastfeeding practices in China: a meta-aggregation of qualitative studies. Matern Child Nutr. 2021;17(4):e13251.

- Nommsen-Rivers LA, Chantry CJ, Peerson JM, et al. Delayed onset of lactogenesis among first-time mothers is related to maternal obesity and factors associated with ineffective breastfeeding. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92(3):574–584.

- Preusting I, Brumley J, Odibo L, et al. Obesity as a predictor of delayed lactogenesis II. J Hum Lact. 2017;33(4):684–691.

- Garner CD, McKenzie SA, Devine CM, et al. Obese women experience multiple challenges with breastfeeding that are either unique or exacerbated by their obesity: discoveries from a longitudinal, qualitative study. Matern Child Nutr. 2017;13(3):e12344.

- De Bortoli J, Amir LH. Is onset of lactation delayed in women with diabetes in pregnancy? A systematic review. Diabet Med. 2016;33(1):17–24.

- Demirci J, Schmella M, Glasser M, et al. Delayed lactogenesis II and potential utility of antenatal milk expression in women developing late-onset preeclampsia: a case series. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):68.

- Froh EB, Lee R, Spatz DL. The critical window of opportunity: lactation initiation following cesarean birth. Breastfeed Med. 2021;16(3):258–263.

- Gao C, Sun X, Lu L, et al. Prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus in mainland China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Diabetes Investig. 2019;10(1):154–162.

- Dewey KG, Nommsen-Rivers LA, Heinig MJ, et al. Risk factors for suboptimal infant breastfeeding behavior, delayed onset of lactation, and excess neonatal weight loss. Pediatrics. 2003;112(3 Pt 1):607–619.

- Scott JA, Binns CW, Oddy WH. Predictors of delayed onset of lactation. Matern Child Nutr. 2007;3(3):186–193.

- Dimitraki M, Tsikouras P, Manav B, et al. Evaluation of the effect of natural and emotional stress of labor on lactation and breast-feeding. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016;293(2):317–328.