Abstract

Introduction: Hypernatremic dehydration in neonates is an uncommon but serious reason for re-hospitalization, especially in exclusively breastfed neonates. The aim was to study the incidence, associated maternal and neonatal characteristics and risk factors, and presenting features of neonatal hypernatremic dehydration (NHD).

Methods: A prospective study design was employed to enroll full-term newborns admitted with serum sodium concentrations of ≥145 mEq/L from April 2022 to March 2023 at a tertiary care rural hospital. Maternal and neonatal characteristics and breastfeeding practices of these mother-baby pairs were recorded and observed. Healthy control for every mother-baby pair was taken. Ethical clearance and informed consent were obtained from mothers.

Result: 34 newborns out of total 672 NICU admissions were admitted due to NHD, with an incidence of 4.7%. Primiparous mothers were 23 (67.6%) in the cases and 10 (29.4%) in the control group (p = 0.0017). Disparity in maternal breastfeeding practices of cases, such as delayed initiation time 2.3 h vs. 1.27 h (p < 0.0001), less frequency of breastfeeding 6.5 times vs. 9.3 times (p < 0.0001), and duration of breastfeeding sessions 23.3 min vs. 32 min (p = 0.0014) respectively in cases and controls were found to be potential contributing factors. 61.7% of mothers had breast issues in the cases and 17.6% in the control group (p = 0.0002) with average LATCH score of 4.29 in cases as compared to 8.08 in controls (p < 0.0001) at time of baby’s admission to NICU. The average neonatal age at presentation was six days and average weight loss was 11.4% in cases vs. 2.8% in controls (p < 0.0001). The main presenting features were excessive weight loss 30 (88.2%), lethargy 20 (58.8%), jaundice 18 (52.9%) and fever 14 (41.1%).

Conclusion: Neonatal hypernatremic dehydration (NHD) poses a significant clinical challenge, particularly in full-term, exclusively breastfed healthy neonates. We found an incidence of 4.7%. Delayed initiation of breastfeeding, inadequate breastfeeding techniques, and maternal breast-related issues were significant contributors to NHD. Primiparous mothers were found to be at higher risk, emphasizing the need for targeted breastfeeding education and support for primiparous mothers. The study reaffirmed the critical role of frequent and effective duration of breastfeeding and daily weight monitoring for preventing NHD.

Introduction

Exclusive breastfeeding is endorsed for the initial six months in newborns. It is sufficient for every nutritional need of a baby during the first six months fulfilling all micro and macronutrients, calories, and even water such that there is no need to give anything above breastfeeding. There is ample evidence that states the health benefits of exclusive breastfeeding for mother and baby [Citation1,Citation2]. But breastfeeding is not a simple or natural job; it is a skill that must be taught to nursing mothers, especially during the early postnatal period and in new mothers, as these mothers face many barriers and hurdles in breastfeeding socially and physically [Citation3]. Adequate breastfeeding of the baby depends on various factors, such as effective milk production and output and proper delivery of breast milk to the baby. Adequate delivery of milk to baby is determined by appropriate attachment of neonate and proper suck, confident mother, how frequent and for how much duration she feeds the baby. Baby should be breastfed at least 8-10 times daily, with a minimum of 15-30 min each session, emptying one breast each time (4). In the early postpartum period, initiation of breastfeeding is difficult due to several reasons. These include cesarean section, painful conditions in the mother making her less motivated for breastfeeding, inappropriate position, and attachment of baby by new and anxious mothers leading to decrease output and delivery of milk. Some local rituals prohibit early initiation of breastfeeding, hence delaying mother-baby bonding. Furthermore, various nipple and breast issues make the continuation of appropriate and adequate breastfeeding a problematic task.

A healthy term baby with a birth weight appropriate for gestational age (AGA) typically loses weight daily of approximately three percent daily during the first seven days of life. By the tenth day, they usually regain their birth weight, with the maximum weight loss reaching up to ten percent. Breastfeeding issues that lead to inadequate breastfeeding and milk supply to baby, in exclusively breastfed babies can cause excessive weight loss beyond the expected range giving rise to serious complications such as neonatal hypernatremic dehydration (NHD) [Citation4,Citation5]. NHD is a very overlooked problem in newborns but sometimes leads to serious complications such as seizures, intracranial hemorrhage, cerebral edema, and vascular thrombosis [Citation6–8]. In our prospective study, we investigated the incidence, maternal and newborn characteristics, presenting symptoms, clinical and laboratory features in newborns with NHD getting admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). We compared them with healthy, matched controls as mother-baby pairs coming for routine follow-up in the out-patient department.

Material and methods

Our prospective study was conducted in a tertiary care center in central India, Shalinitai Meghe Hospital and Research Center, from April 2022 to March 2023. Our setting has approximately 2000 deliveries per year. Postnatal routine counseling and checkup are done by a pediatric resident and consultant with special care for breastfeeding. Vaginally delivered mothers are discharged on the fifth day, and cesarean section delivered mothers are discharged on the eighth day in normal circumstances without any complications to mother or baby. In the meantime, mothers are counseled, educated, and motivated for exclusive breastfeeding, and any breastfeeding-related issues are dealt in pediatric rounds of the postnatal ward. Ethical clearance was obtained from our Institutional Ethics Committee. We had a total of 2179 deliveries in the said study period. Total NICU admissions were 672 in the period of study, out of which 35 had hypernatremia and were included as cases for further evaluation of associated maternal and neonatal characteristics and risk factors, and presenting features of NHD based on following inclusion criteria –

serum sodium >145 mEq/L at the time of admission.

term baby (completed 37weeks) with weight appropriate for gestational age (AGA) at birth (>2.5kg).

was shifted to mother side at the time of birth without any complication, or NICU stay.

rehospitalized within 28 days of life.

One case was excluded from the study due to a positive sepsis screen at admission. Finally, a total of 34 mother-baby pairs were taken into the study. Parallelly, 34 mother-baby pairs were selected as controls having healthy term babies (completed 37 weeks, birth weight >2.5 kg, serum sodium <145mEq/L) from routine follow-up in outpatient. Informed consent was obtained from participating mothers.

We recorded various blood and other investigations, maternal antenatal and natal issues, breastfeeding issues, and weights of babies at birth and at admission in NICU, clinical features of babies at admission. Blood investigations sent were serum sodium, potassium, urea, creatinine, complete blood count with hematocrit, C-reactive protein, blood culture (where required), and direct and indirect serum bilirubin. Neurosonogram and blood gas analysis were performed wherever clinically needed. Maternal factors recorded were age, parity, weight gain in pre-post pregnancy, education, pregnancy complications, breast size increase pre-post pregnancy, breast issues and breastfeeding position, let-down reflex, time of breastfeeding initiation, and breastfeeding sessions per day. Breastfeeding information and issues were collected by direct questioning, observing breastfeeding sessions, examining the breasts, and documenting in our “breastfeeding monitoring proforma” (attached as an Appendix). Breastfeeding issues encountered were mastitis, cracked nipples, flat/inverted nipples, and big nipples, difficulty in holding baby in proper position (breastfeeding position was taken as a classical position with the baby’s back fully supported along with the head in a straight line, the baby’s abdomen touching the mother’s chest, mother having complete back support). The latching and swallowing were observed during sessions. These issues were quantified with LATCH scoring for comparison. The knowledge and experience of expert senior professionals in the field were instrumental in shaping the content and structure of the proforma, guaranteeing its relevance and effectiveness in collecting essential information related to breastfeeding practices.

We matched the mode of delivery of cases and controls to remove the confounding factor of normal vaginal delivery versus cesarean section. Neonatal factors included age at admission, 5-min APGAR score, gestational age, sex, birth weight, admission weight, percentage weight loss, duration of breastfeeding per session, and the number of times urine was passed per day. Let down reflex was milk production and ejection on sucking of the nipple by the baby. All babies in the case group were managed in NICU with supervised feeding or intravenous fluids.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyzes were performed using SPSS 22.0. Values were expressed as mean ± SD and percentages. The Student’s t-test assessed the comparisons of two groups in the case of continuous data, and categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test. P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Maternal characteristics

( near here) We compared the characteristics of both cases and control, with a total of 68 mothers in the study (34 in each group). We found no significant difference in mother education, pre-post-pregnancy weight gain, or the presence of breast enlargement during pregnancy (p > 0.05, ).

Table 1. Maternal and neonatal characteristics in cases and controls.

Maternal age, primiparous, breast problems, improper latching and holding, absence of letdown reflex, and absence of empty breast after feeding were significantly more in cases than controls (p < 0.05, ). The LATCH score was significantly better in controls than cases (p < 0.0001, ).

23 (67.6%) mothers of newborns with NHD were primiparous in cases as compared to 10 (29.4%) in controls (p < 0.0017). In cases, 31 (91.1%) had delayed or absent letdown reflexes with less milk production. Six of these mothers had poor pregnancy and postpartum breast enlargement. 21(61.7%) mothers of babies with NHD had breast issues (six had mastitis, five had cracked nipples eight had flat nipples, and two had big nipples) with significant p = 0.0002. On examining breastfeeding sessions of mothers of babies having NHD, 25 (73.5%) mothers were found to have inappropriate baby-holding positions or improper attachment of the baby to the breast (p < 0.0001). Only 23 (67.6%) mothers had empty breast feelings after breastfeeding in the NHD group compared to 34 (100%) in the control group (p = 0.0003).

Neonatal characteristic

The incidence of NHD was 4.7% (34 out of a total of 672 admissions to the NICU). There were no significant differences between the two groups in sex, APGAR score, or gestational age. There was also no significant difference in birth weight, but weight at admission to NICU was significantly low in the NHD group (p < 0.0001). The neonatal age of admission to NICU for NHD ranged from 3 to 15 days (average 6.5 ± 2.9 days).

The average number of feeding sessions per day in the NHD group was 6.5 times while in the control group, it was 9.3 times per day. The average duration of each feeding session was 23 min in cases compared to 32 min in the control group. There were more outliers with less than 10 min (10 babies) and more than 40 min (4 babies) in the NHD group, showing more ineffectiveness of breastfeeding in the cases. Urine was passed on an average of three times in cases compared to more than eight times in controls. The average weight loss percentage since birth in babies with NHD was 11.4%, while only 2.8% in controls. At presentation, 30 newborns (88.2%) had >10% weight loss, 20 (58.8%) had poor feeding/lethargy, 18 (52.9%) had jaundice, 14 (41.1%) had a fever, 19 (55.8%) had excessive sleepiness, and two had a seizure.

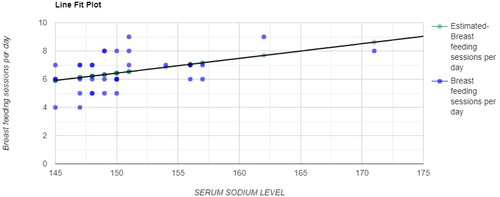

The mean serum sodium concentration in newborns with NHD was 150.67 mEq/L, and the median was 149 mEq/L (147-162 mEq/L). In the correlation calculation, there was a moderate direct relationship between serum sodium levels and the number of daily breastfeeding sessions, highlighting the importance of frequent feedings ().

Figure 1. Correlation (R) = 0.4469 p-value = 0.008, a moderate direct relationship between serum sodium level and breastfeeding sessions per day.

The most common consequence in newborns with NHD was acute kidney injury (AKI) with mean serum creatinine levels of 1.10 ± 0.22 mg/dL and mean urea levels of 59 ± 1.7 mg/dL and decreased urine output in the last 12 h.

The mean hospital stay for complete hypernatremia correction was 2.8 days. Only 7 out of 34 required intravenous fluids, while others were treated with supervised and measured “katori spoon” feeding along with training of mothers, resolving breastfeeding issues, and making them confident.

Discussion

The incidence of NHD has surprisingly increased with the implementation of exclusive breastfeeding under the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative (B.F.H.I.) [Citation7]. In our study, we found an incidence of NHD of 4.7%. Previous studies have reported a wide range of incidences, 3.4%, 1.9%, 0.16%, 10%, 1.33%, 5.6% [Citation4,Citation9–13]. The incidence in our study was in the range of previous studies. Hypernatremia is a dangerous condition if it is not detected in early stages. Consequences of moderate to severe NHD can be brain hemorrhage, cerebral infarction, brain edema, acute kidney injury, liver failure, peripheral venous and arterial thrombosis, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and even death [Citation6,Citation8]. A serum sodium excess of 160 mEq/L is correlated with increased morbidity and mortality [Citation14].

The leading cause of NHD is inadequate milk supply to the baby, which may be due to low maternal milk production or ineffective milk delivery to a baby, or reasons that can be a combination of both. Reduced breastfeeding frequency is related to the rise in breast milk sodium levels. Usually, colostrum contains a mean sodium concentration of 64.8 ± 4.4 mmol/L, which gradually decreases to 7.0 ± 2.0 mmol/L in mature milk in two weeks [Citation15]. Failure to drop in the concentration of sodium levels in breast milk is seen in cases of decreased breastmilk production [Citation16,Citation17]. In a case report, breastmilk sodium was monitored till the 30th day of neonate and found to be twice the normal range, concluding that the delayed maturation of breast milk may be a risk factor for NHD [Citation18].

Early initiation of breastfeeding has an impact on milk production and breastfeeding continuation. Our study has shown that the cases had delayed breastfeeding initiation than the controls (p < 0.0001). Mode of delivery directly impacts early initiation of breastfeeding, having delayed initiation of breastfeeding in cesarean section [Citation19]. Many studies have established that cesarean section is more associated with NHD [Citation12,Citation20]. Although in a study, Saxena et al. [Citation10] found that feeding is more supervised in a cesarean section until the mother is capable of caring for baby feedings. Therefore, we matched cesarean sections and vaginal deliveries in cases and controls to remove bias of mode of delivery in incidence of NHD. Hence the findings of our study matched various previous studies concluding that delayed initiation of first breastfeeding was a critical associated risk factor for NHD [Citation20,Citation21].

In our study, 61.7% of mothers in the NHD group had breast problems in the form of mastitis, cracked nipples, flat nipples, and large nipples, and around 75% of mothers had problems with holding babies and proper latching, corresponding to various previous studies [Citation11,Citation22]. Several previous studies have also reported that the incidence of NHD is higher in babies with primiparous mothers [Citation10,Citation23,Citation24]. The expected reason is ineffective galactopoiesis in the first few days in a first-time mother, coupled with no experience in dealing with the signals of newborn and postpartum exhaustion. New mothers had more breast-nipple issues and holding-latching issues. This study also found that almost two-thirds of the mothers were primiparous. Hence inspection of the breast is an integral part of the examination in the immediate postpartum period, and education of, especially among new mothers, is also essential regarding proper holding of the baby, latching the baby to the breast, and taking care of the breast issues in the early postpartum period. Early breast examination and education will make mothers confident and motivated for appropriate breastfeeding and help them identify early cues and danger signs of NHD in their babies. The mean age of presentation of hypernatremia was six days in our study. A similar age of presentation has been reported in a previous study by Sarin et al. [Citation14] with a range of 6-10 days; others reported a mean of 4.3 days and seven days [Citation5,Citation25].

The presenting features of babies in our study were lethargy or poor feeding at 58.8%, excessive sleepiness accounting for 55.8%, jaundice at 52.9%, fever at 41.1%, and 5.8% with seizures. Almost 88% of neonates in the NHD group experienced more than 10% weight loss at presentation, with the mean percentage weight loss recorded at 11.4%, compared to 2.8% in the control group (p < 0.0001). Our finding matched that of Ergenekon et al. who reported the mean weight loss percentage 11.5%. Uras et al. [Citation13] in their research, concluded that a weight loss percentage of more than 7% is increasingly associated with NHD. Similarly, Del-Castillo et al. [Citation7] also concluded that taking 10% weight loss as standard is an overestimation to newborns’ tolerance of weight loss. It is physiological to lose weight in the early neonatal period, but there is a proven difference in weight loss between healthy breastfed newborns and babies with NHD. Therefore, it is vital to have a policy of weighing babies in the early neonatal period. Iyer et al. [Citation26] studied the effect of the policy of weighing babies. They found that after the policy there was a significant reduction in percentage weight loss, maximum serum sodium increase, and higher frequency of breastfeeding. In the mentioned context, developing and using "weight loss charts” is essential, which can be valuable tools in early detection and preventing newborns from developing breastfeeding-associated hypernatremic dehydration [Citation27].

The limitation of this study is that this study was conducted in a single center, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to a broader population. Incidence of NHD is subjected to regional variations in healthcare practices and patient demographics. Also, this study has provided data at a specific point in time, longitudinal data on the follow-up of the cases will allow a more accurate understanding of cases of the course and outcomes of NHD over time. However, our study provided detailed information on various factors related to NHD, including, maternal and neonatal characteristics and risk factors, clinical presentations, and potential complications. These comprehensive data provide a deeper understanding of the problem. Our study highlights the importance of using weight loss charts as a tool for early detection and prevention of breastfeeding associated NHD and suggests a practical intervention for healthcare providers.

Conclusion

Neonatal hypernatremic dehydration (NHD) poses a significant clinical challenge, particularly in term, exclusively breastfed healthy neonates. In our prospective study, we found an incidence of 4.7%, highlighting the importance of vigilant monitoring of breastfeeding practices to identify issues in breastfeeding promptly. Maternal factors such as delayed breastfeeding initiation, inadequate breastfeeding techniques, and maternal breast-related issues were identified as significant contributors to NHD. Primiparous mothers were found to be at higher risk, emphasizing the need for targeted breastfeeding education and support for primiparous mothers. Neonatal characteristics, including weight loss beyond expected ranges and decreased urine output, were key indicators of NHD along with other presenting features such as lethargy, jaundice. The study reaffirmed the critical role of frequent and effective breastfeeding in maintaining proper hydration levels in neonates and preventing NHD.

In essence, our findings highlight the critical role of sound breastfeeding practices, early support for new mothers, and strategic use of tools like daily weight monitoring and weight loss charts to prevent and address NHD in infants.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (47.3 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

STROBE CHART mentioned in Appendix.

Data availability statement

The data supporting this study’s findings are available in Figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.23599305.v1. Ref. [Citation28].

Additional information

Funding

References

- Eidelman AI. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk: an analysis of the American academy of pediatrics 2012 breastfeeding policy statement. Breastfeed Med. 2012;7(5):1–7. Epub 2012 Sep 4. PMID: 22946888. doi:10.1089/bfm.2012.0067.

- Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJ, et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet. 2016;387(10017):475–490. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01024-7.PMID: 26869575.

- Mundagowa PT, Chadambuka EM, Chimberengwa PT, et al. Barriers and facilitators to exclusive breastfeeding practices in a disadvantaged community in Southern Zimbabwe: a maternal perspective. World Nutr. 2021;12(1):73–91. doi:10.26596/wn.202112173-91.

- Bhat SR, Lewis P, David A, et al. Dehydration and hypernatremia in breast-fed term healthy neonates. Indian J Pediatr. 2006;73(1):39–41. PMID: 16444059. doi:10.1007/BF02758258.

- Wang AC, Chen SJ, Yuh YS, et al. Breastfeeding-associated neonatal hypernatremic dehydration in a medical center: a clinical investigation. Acta Paediatr Taiwan. 2007;48(4):186–190. PMID: 18265538.

- Musapasaoglu H, Agildere AM, Teksam M, et al. Hypernatraemic dehydration in a neonate: brain MRI findings. Br J Radiol. 2008;b81(962):e57-60–e60. PMID: 18238917. doi:10.1259/bjr/28766369.

- Del Castillo-Hegyi C, Achilles J, Segrave-Daly BJ, et al. Fatal hypernatremic dehydration in a term exclusively breastfed newborn. Children (Basel). 2022;9(9):1379. PMID: 36138688; PMCID: PMC9498092. doi:10.3390/children9091379.

- Bhattacharya D, Angurana SK, Sundaram V, et al. Cerebral sinovenous thrombosis due to hypernatremic dehydration in a neonate. Neurol India. 2021;69(1):164–166. PMID: 33642292. doi:10.4103/0028-3886.310090.

- Nair S, Singh A, Jajoo M. Clinical profile of neonates with hypernatremic dehydration in an outborn neonatal intensive care unit. Indian Pediatr. 2018;55(4):301–305. Epub 2018 Feb 9. PMID: 29428916.

- Saxena A, Kalra S, Shaw SC, et al. Correction of hypernatremic dehydration in neonates with supervised breast-feeding: a cross-sectional observational study. Med J Armed Forces India. 2020;76(4):438–442. Epub 2019 Jul 11. PMID: 33162653; PMCID: PMC7606081. doi:10.1016/j.mjafi.2019.05.002.

- Yaseen H, Salem M, Darwich M. Clinical presentation of hypernatremic dehydration in exclusively breastfed neonates. Indian J Pediatr. 2004;71(12):1059–1062. doi:10.1007/BF02829814.

- Samayam P, Ravichander B. Hypernatremia and excessive weight loss in exclusively breastfed term infants in early neonatal period. Indian J Child Health. 2017;4(1):15–17. doi:10.32677/IJCH.2017.v04.i01.005.

- Uras N, Karadag A, Dogan G, et al. Moderate hypernatremic dehydration in newborn infants: retrospective evaluation of 64 cases. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2007;20(6):449–452. PMID: 17674254. doi:10.1080/14767050701398256.

- Sarin A, Thill A, Yaklin CW. Neonatal hypernatremic dehydration. Pediatr Ann. 2019;48(5):e197–e200. PMID: 31067335. doi:10.3928/19382359-20190424-01.

- Heldrich FJ, Shaw SS. Case report and review of literature: hypernatremia in breast-fed infants. Md Med J. 1990;39(5):475–478. 2185394.

- Humenick SS, Hill PD, Thompson J, et al. Breast-milk sodium as a predictor of breastfeeding patterns. Can J Nurs Res. 1998;30(3):67–81. PMID: 10030186.

- Mujawar NS, Jaiswal AN. Hypernatremia in the neonate: neonatal hypernatremia and hypernatremic dehydration in neonates receiving exclusive breastfeeding. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2017;21(1):30–33. PMID: 28197048; PMCID: PMC5278587. doi:10.4103/0972-5229.198323.

- Peters JM. Hypernatremia in breast-fed infants due to elevated breast milk sodium. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1989;89(9):1165–1170. doi:10.1515/jom-1989-890913.

- Lamba I, Bhardwaj MK, Verma A, et al. Comparative study of breastfeeding in caesarean delivery and vaginal delivery using LATCH score and maternal serum prolactin level in early postpartum period. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2023;73(2):139–145. Epub 2022 Nov 17. PMID: 37073235; PMCID: PMC10105808. doi:10.1007/s13224-022-01698-9.

- Lavagno C, Camozzi P, Renzi S, et al. Breastfeeding-Associated hypernatremia: a systematic review of the literature. J Hum Lact. 2016;32(1):67–74. Epub 2015 Nov 3. PMID: 26530059. doi:10.1177/0890334415613079.

- Caglar MK, Ozer I, Altugan FS. Risk factors for excess weight loss and hypernatremia in exclusively breast-fed infants. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2006;39(4):539–544. Epub 2006 Apr 3. PMID: 16612478. doi:10.1590/s0100-879x2006000400015.

- Boskabadi H, Maamouri G, Ebrahimi M, et al. Neonatal hypernatremia and dehydration in infants receiving inadequate breastfeeding. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2010;19(3):301–307. PMID20805072.

- Celik K, Ozbek A, Olukman O, et al. Hypernatremic dehydration risk factors in newborns: Prospective case-Controlled study. Klin Padiatr. 2021;233(4):194–199. English Epub 2021 Jul 21. PMID: 34289509. doi:10.1055/a-1443-6017.

- Shivanagouda J, Gayathri K, Roopa BN. Hypernatremic dehydration in exclusively breast fed neonates: a clinical study. J PediatrRes. 2017;4(08):525–530. doi:10.17511/ijpr.2017.i08.05.

- Kumar M, Pattar R, Yelamali B, et al. Clinical spectrum and outcome of dehydration fever in term healthy neonates -a teaching hospital based prospective study. Med Innov. 2020;6:20–23.

- Iyer NP, Srinivasan R, Evans K, et al. Impact of an early weighing policy on neonatal hypernatraemic dehydration and breast feeding. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93(4):297–299. Epub 2007 May 2. Erratum in: arch Dis Child. 2008 Jun;93(6):547. PMID: 17475691. doi:10.1136/adc.2006.108415.

- van Dommelen P, Boer S, Unal S, et al. Charts for weight loss to detect hypernatremic dehydration and prevent formula supplementing. Birth. 2014;41(2):153–159. Epub 2014 Apr 3. PMID: 24698284. doi:10.1111/birt.12105.

- Arora I, Juneja H. 01 Neonatal hypernatremic dehydration in breastfed neonates: a prospective study unmasking the influences of breastfeeding practices and early weight monitoring. Figshare. Dataset. 2023. doi:10.6084/m9.figshare.23599305.v1.