Abstract

Background

In recent years, neonatal hearing screening (NHS) has gained rapid traction in both developed and developing nations. However, the efficacy of these efforts depends on comprehensive standardization across all screening facets. This study aimed to assess the status and quality of NHS by investigating the knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and practices of hearing screening practitioners regarding NHS.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was conducted, and an online questionnaire based on the knowledge-attitude/belief (A/B)-practice model was distributed to all NHS practitioners in Luzhou, western China. Valid questionnaires were examined and uniformly graded.

Results

A total of 63 valid questionnaires were collected. The practitioners were mainly female (96.83%), with nursing backgrounds (63.49%), and undergraduate degrees (66.67%). Most had ≤5 years of experience (74.60%) and had junior/intermediate titles (93.65%). The NHS within the Luzhou area started in 2006 with provincial institutions, expanding to 42 institutions by 2022. Statistically significant correlations were observed between the A/B score and the conducting years of each NHS institution (p < .05) as well as between the Knowledge (K) and Practice (P) scores (p < .01). No significant correlation was found between the K score, P score, A/B score, and working years of practitioners (p > .05), or in the total score of NHS institutions at different levels or in different counties by one-way ANOVA (p > .05).

Conclusions

It has been 17 years since the first medical institution in Luzhou launched NHS, and the overall performance of practitioners from different institutions has been consistent in terms of their knowledge, attitudes, or level of practice. However, there is room for further improvement in both the professional development of individuals and aspects related to work, such as health education and long-term follow-up.

Introduction

Hearing loss stands as the most common congenital defect affecting newborns globally, impacting approximately 34 million children, with a prevalence rate of 0.5–5 per 1000 newborns and infants [Citation1]. The World Health Organization predicts that over 700 million individuals will face disabling hearing loss by 2050 [Citation1]. Timely detection is essential, facilitating prompt interventions and averting setbacks in language acquisition and speech development. Consequently, neonatal hearing screening (NHS) assumes a pivotal role in early detection [Citation2], sparking growing interest, particularly in developing countries, where its cost-effectiveness is evident [Citation3–5]. In China, despite a notable increase in NHS coverage from 29.9% in 2008 to 86.5% in 2016 [Citation6], there remains a disparity compared to developed nations like the USA (98.0%) [Citation7], the UK (97.5%) [Citation8], Poland (96.0%) [Citation9], and some regions of Italy (99.3%) [Citation10]. Regional variations within China also exist, with eastern provinces reaching 93.1%, compared to 84.9% and 79.4% in central and western provinces. These disparities may stem from differences in NHS initiation, economic gaps between regions, limited healthcare resources, and lower prioritization of NHS [Citation11,Citation12].

NHS standards and guidelines vary between countries. Studies have shown that the NHS guidelines in the USA and the UK are high quality because of their well-established hearing screening programs, early initiation of screening, and comprehensive guidelines [Citation13,Citation14]. Similarly, China’s Technical Specification for Newborn Screening (2010 version), tailored to its developmental stage, maintains a high level of coherence and credibility [Citation15]. However, regional variations exist in China, such as Fujian Province requires practitioners have five years of experience [Citation16], whereas Hunan Province mandates three years [Citation17]. It’s worth mentioning that practitioners’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices are critical to the quality of screening. Studies have noted that practitioners in different specialties vary in the knowledge of NHS and show diversity in attitudes and practices [Citation18–22]. The accuracy of screening may be compromised by some practitioners due to a lack of systematic training [Citation18] or inadequate knowledge of NHS [Citation23–25]. Some practitioners demonstrate noncompliance and low regard for published guideline, further reducing the quality of screening [Citation21,Citation24]. Of concern is the failure of practitioners to keep up to date with the latest developments and updates in NHS, which may make screening methods lagging behind [Citation26].

The screening rate and quality varied according to factors such as regional income level, birth rate, and maternity distribution [Citation27]. Eighty percent of people with disabling hearing loss live in low- and middle-income countries [Citation28]. Luzhou, situated in the economically less developed southern Sichuan region, boasts a population exceeding 4.2 million within an area of approximately 12,000 km2. While the implementation of NHS in Luzhou has been gradual, there are concerns that it may not align with established normative standards. Hence, this study delves into the knowledge, attitudes, and practices among NHS practitioners in Luzhou. We hope that this study will offer a fundamental understanding of practitioner perspectives and practices in our region, contributing support for the normative implementation of NHS.

Materials and methods

Questionnaire respondents

This study surveyed frontline clinical practitioners and professionals involved in NHS work in the entire Luzhou area. We aimed to involve at least one representative from each eligible NHS institution in the questionnaire survey, excluding administrative, logistical, or internship staff.

Instrument

We conducted an online questionnaire survey using the Knowledge-Attitude-Belief-Practice (KABP) model. The questionnaire consisted of two parts. The first part collected demographic information of respondents. The second part focused on the core content of the questionnaire, designed based on the Technical Specification for Newborn Hearing Screening (2010 version) [Citation29] and Clinical Audiology section on NHS [Citation30]. It aimed to assess practitioners’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to NHS. Following the KABP model, the second part was further divided into knowledge-related questions (items 8, 9, 10, 14, 16, and 20), attitude- and belief-related questions (items 24, 25, and 27), and practice-related questions (items 11, 12, 13, 15, 17, 18, 19, 21, 22, and 23). Each segment was scored individually, resulting in K, attitude/belief (A/B), and P to ensure the validity and clarity of the questionnaire, a preliminary version was tested with hearing screening practitioners at The Affiliated Hospital of Southwest Medical University. Their feedback led to iterative improvements in the content and structure of the questionnaires. This preliminary survey confirmed the clarity and surface validity of the questionnaire.

Distribution and collection of questionnaires

We received support from the Luzhou Branch Center for Neonatal Hearing Impairment Diagnosis and Treatment in Sichuan Province as well as the Luzhou Hearing Screening Office. The online questionnaire was distributed as a formal administrative document notification after informed consent and administrative authorization were obtained. It was accessible for 30 days and completed voluntarily and anonymously. We also ensured that at least one individual from each medical institution participated in the study. If we encountered ambiguous responses that could have affected the analysis, we proactively contacted the respective agency’s leader by phone to seek clarification.

Statistical analysis

The study commenced by presenting basic information. Data from the second part were analyzed using SPSS 23.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL), generating descriptive statistics for respondents’ basic information. Spearman’s correlation analysis explored relationships between various scores and relevant factors. One-way ANOVA compared total scores of NHS institutions across different grades and counties. Subjective questionnaire responses were summarized based on key points, and insights from open-ended questions were independently documented by two authors and not scored, resolving any disparities through collaborative discussion.

Results

The basic characteristics of the respondents

Ultimately, a total of 63 valid questionnaires were obtained. The basic information of the respondents () is as follows: the gender distribution was predominantly female (96.83%); the educational background consisted mostly of undergraduate degrees (66.67%); the primary profession reported was nurse (63.49%), followed by obstetrician–gynecologist (12.70%); the majority of practitioners had less than or equal to five years of working experience (74.60%); and the prevalent job titles were junior and intermediate positions (93.65%).

Table 1. The basic characteristics of respondents.

Overview of newborn hearing screening coverage in the Luzhou area

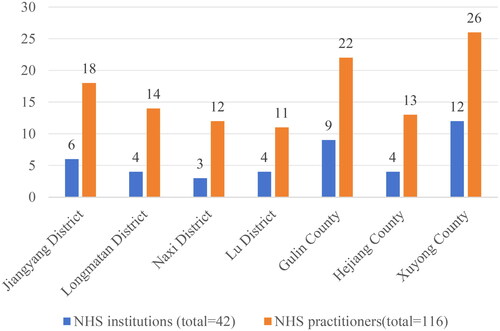

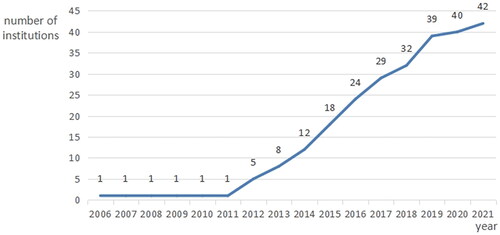

The Luzhou area comprises four counties and three districts, with a population exceeding 4.2 million. The survey covered all NHS-conducting medical institutions (42 institutions) and majority of NHS practitioners (63 out of 116) in the region (). Classified by the level of medical institutions conducting NHS, there were 15 primary institutions, 13 secondary institutions, and 14 tertiary medical, maternal. From the time of implementation, the work first began in 2006, initiated by a provincial tertiary medical institution, to the 2012–2019 large-scale succession, and the rise in the last two years tapered off ().

Quality profiling of NHS in Luzhou area (KABP model)

Knowledge

More than half of the respondents (65.08%) reported receiving systematic training in NHS at the provincial or municipal level. About 61.90% of the participants mentioned regularly learning about the latest developments related to NHS to stay abreast of the latest advancements. However, 22.22% admitted a lack of comprehensive knowledge regarding the parameters of screening equipment, restricting them to basic operations. A consensus emerged on the purpose and significance of health education in hearing screening (). Correlations between the K score and working years of practitioners were tested, revealing no statistically significant correlation (r = 0.017, p > .05) ().

Table 2a. Questions in the questionnaire related to knowledge and attitudes/belief.

Table 2b. Questions in the questionnaire related to practice.

Table 3. Spearman’s correlation analysis.

Attitude/belief

Some respondents (39.68%) thought that NHS practice in their institutions generally adhered to relevant norms and did not necessitate further standardization, and the vast majority (95.24%) concurred that standardized work could improve the accuracy and pass rate of screening (). The open-ended question regarding recommendations to standardize NHS in Luzhou city (item 27) garnered eight comprehensive responses. Five participants stressed the importance of heightened publicity, two suggested regular training, and one proposed the sharing of big data. Despite the limited responses, all contributors underscored the urgency of promoting awareness about NHS and expressed anticipation for corresponding training initiatives. To explore potential relationships, Spearman’s correlation analyses were conducted. First, a correlation was examined between the A/B score and the conducting years of each institution, revealing a statistically significant correlation (p < .05). Similarly, Spearman’s correlation analysis was conducted between the working years of practitioners and the conducting years of each institution, uncovering a statistically significant correlation (p < .01). However, the correlation between the A/B score and the working years of practitioners was not statistically significant (p > .05) ().

Practice

Otoacoustic emission (OAE) was extensively used for primary screening in all NHS institutions in Luzhou, with over 90% equipped with dedicated hearing screening rooms. Most strictly adhered to the Technical Specification for Newborn Hearing Screening (2010 version). In terms of health education, respondents widely agreed on the purpose and significance of NHS (97.62%) and demonstrated a strong understanding of the screening process (92.86%) and its associated aspects. However, there were limited educational efforts (<50%) on hearing loss diagnosis, intervention, and prognosis. Some institutions (45.24%) used sedation for excited newborns during screening. Different institutions targeted distinct screening populations, with general wards achieving a high newborn screening rate (97.62%). Only 66.67% of institutions used both paper and electronic data archiving, while 33.33% relied on a single method (). Spearman’s correlation analysis showed no significant correlation between practitioners’ working years and the P score (p > .05). However, a significant correlation existed between the P- and K-scores (p < .01) in the same context ().

Total score

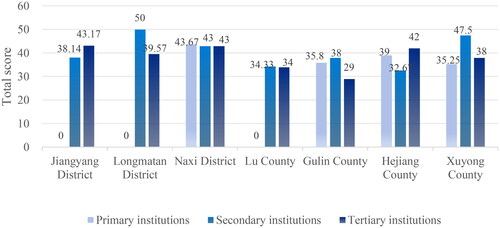

The total score, ranging from 0 to 54, was derived from the sum of the K score, AB score, and P score. Artificial inferences were made based on the respondents’ perspectives, and the mean total scores were classified into three levels (0–32, 33–43, and 44–54) to assess their knowledge, attitudes, or practices relative to the norms. The grading results showed that practitioners in 11 institutions scored low, in 23 institution practitioners were in the middle of the pack, while practitioners in eight institutions received high scores. However, a subsequent one-way ANOVA on the mean total scores of practitioners from agencies at different levels or districts showed that the difference was not statistically significant (p > .05) ().

Discussion

NHS is widely adopted in Luzhou, covering institutions at various levels and reflecting a balanced distribution. The number of NHS institutions has significantly increased over the past decade, possibly linked to the rapid development of medical and healthcare in China [Citation31]. However, this growth has slowed in the past two years, likely due to the unprecedented impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. During the pandemic, centralized training for hearing screening faced challenges, resulting in limited standardized training for new practitioners and the establishment of new screening institutions [Citation32]. The lack of formal education and training may result in practitioners having a poor understanding of screening processes, standards, and techniques, which, in turn, may diminish the accuracy of the screening process.

The fact that shorter work experience and lower titles among hearing screening practitioners indicates the rapid expansion of the screening workforce. Unfortunately, in audiology-related screening tests, many nursing professionals fulfill specialized roles without audiology expertise. This prevalence, coupled with a shortage of audiological professionals across various institutions, may inadvertently lead to a compromise the quality of the screening process [Citation33]. Despite the seemingly straightforward nature of hearing screening, its successful execution requires the collaboration of numerous practitioners [Citation34]. For example, the staffing requirements and specific roles for screening practitioners, testers, and administrative staff are comprehensively outlined in the Hearing Screening Technical Specification (2010 version). A study emphasizes the need for substantial human and material resources, along with strengthened training for hearing screening teams to ensure smooth and successful implementation [Citation35].

In addition, the P and K scores were not significantly correlated with the number of working years for each practitioner, whereas the K score was correlated with the P score. This suggests that the threshold for practitioners working in NHS is not high, but much work experience and theoretical knowledge are needed to improve the quality of hearing screening [Citation36]. The A/B score was positively correlated with the number of years that each NHS institution had been in operation, suggesting that newly established screening institution and their practitioners are not yet motivated to further standardize this work. This may be the result of a combination of factors, including a lack of standardized processes in the early years of an institution’s existence, inexperienced practitioners or a lack of awareness of the importance of processes [Citation11,Citation12]. In order to increase the importance of NHS among practitioners in new institutions, there is a need to inform and educate them about the standardization of NHS in order to increase the importance of the process.

Long-term follow-up poses a significant challenge for all hearing screening institutions [Citation37], especially those in Luzhou with shorter establishment times and lower hospital levels in our study. Previous studies have found that poor healthcare accessibility, incomplete documentation of hearing screening, and lack of knowledge of NHS outcomes among primary care providers increase the risk of lost visit [Citation38]. Socio-demographic factors of infants and parents can also influence adherence to follow-up after NHS referral [Citation39]. In terms of health education, while almost all NHS practitioners agree on its purpose and significance, there is uneven understanding of the content, and awareness of the importance of hearing screening needs enhancement. Studies have also shown that many parents’ lack of awareness of the significance of the NHS may lead them to believe that further screening is not necessary even if their child has a hearing problem [Citation32], which may result in newborns missing out on the golden years of language development. In Luzhou, newborns who did not pass the primary screening were not able to attend hearing screening institutions for rescreening in time, resulting in interruption of the hearing screening process, which can be attributed to both objective factors like remoteness and poor economic conditions, and the lack of attention to rescreening and follow-up mechanisms in these institutions [Citation40]. To enhance the follow-up in Luzhou’s NHS, there is an urgent need to improve internal processes, staff training, and raise public awareness about the significance of hearing screening through social education.

In the present study, practitioners in lower-level NHS institutions score relatively low on knowledge, attitudes, or practices. This may stem from a lack of theoretical knowledge, non-standardized working practices, inadequate management of screening data, and insufficient referral processes between screening and diagnostic institutions [Citation34]. Some practitioners in Luzhou have undergone NHS training but may not meet provincial health administration requirements. Staying informed about the latest NHS developments can enhance expertise and encourage the adoption of advanced techniques [Citation26]. However, some individuals do not actively seek information on the latest developments. Despite these challenges, Spearman’s correlation analysis indicated that the differences in means were not statistically significant. This lack of correlation may be attributed to the maturity of hearing screening practices, well-established systems and industry standards, and comprehensive understanding and mastery of core methods by various healthcare providers.

However, this study had some limitations. First, KABP survey captures opinions, which may not necessarily align with actual practices, and future follow-up through field research and other means may be needed to better reflect the current status of NHS quality. Second, this study was a voluntary sample, not all practitioners participated in the survey, and the portion of practitioners who did not participate in the survey may have contributed to a degree of skewing of the results. In order to improve the robustness of the findings, a stratified sampling method could be used in future studies, taking into account the size of the different levels in the target population.

Conclusions

It has been 17 years since the first medical institution in Luzhou launched NHS, and the overall performance of practitioners from different institutions has been consistent in terms of their knowledge, attitudes, or level of practice. However, there is room for further improvement in both the professional development of individuals and aspects related to work, such as health education and long-term follow-up.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval and consent to participate were obtained from the Luzhou Branch Center for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Neonatal Hearing Impairments in Sichuan Province (No. 5105025092121).

Consent form

The questionnaire was designed to be anonymous and informed consent was obtained from each respondent. The data were kept confidential, and the results did not identify the respondents personally.

Author contributions

Dan Lai and Hongli Lan contributed to the study conception and design. Hongli Lan supervised all aspects of its execution and wrote the manuscript. Maojie Liu assisted with data analysis and interpretation and wrote the manuscript; Dan Lai contributed to manuscript revision. All authors helped to conceptualize ideas, interpret findings, and review the drafts of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all respondents for participating in the survey.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Olusanya BO. Highlights of the new WHO report on newborn and infant hearing screening and implications for developing countries. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;75(6):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2011.01.036.

- Escobar-Ipuz FA, Soria-Bretones C, García-Jiménez MA, et al. Early detection of neonatal hearing loss by otoacoustic emissions and auditory brainstem response over 10 years of experience. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;127:109647. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2019.109647.

- Li PC, Chen WI, Huang CM, et al. Comparison of newborn hearing screening in well-baby nursery and NICU: a study applied to reduce referral rate in NICU. PLOS One. 2016;11(3):e0152028. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152028.

- Bussé AM, Qirjazi B, Goedegebure A, et al. Implementation of a neonatal hearing screening programme in three provinces in Albania. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;134:110039. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2020.110039.

- Malesci R, Del Vecchio V, Bruzzese D, et al. Performance and characteristics of the newborn hearing screening program in Campania region (Italy) between 2013 and 2019. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2022;279(3):1221–1231. doi: 10.1007/s00405-021-06748-y.

- Yuan X, Deng K, Zhu J, et al. Newborn hearing screening coverage and detection rates of hearing impairment across China from 2008–2016. BMC Pediatr. 2020;20(1):360. doi: 10.1186/s12887-020-02257-9.

- Subbiah K, Mason CA, Gaffney M, et al. Progress in documented early identification and intervention for deaf and hard of hearing infants: CDC’s hearing screening and follow-up survey, United States, 2006–2016. J Early Hear Detect Interv. 2018;3(2):1–7.

- Wood SA, Sutton GJ, Davis AC. Performance and characteristics of the newborn hearing screening programme in England: the first seven years. Int J Audiol. 2015;54(6):353–358. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2014.989548.

- Greczka G, Wróbel M, Dąbrowski P, et al. Universal neonatal hearing screening program in Poland – 10-year summary. Otolaryngol Pol. 2015;69(3):1–5. doi: 10.5604/00306657.1156325.

- Bubbico L, Tognola G, Grandori F. Evolution of Italian universal newborn hearing screening programs. Ann Ig. 2017;29(2):116–122.

- Harris MS, Dodson EE. Hearing health access in developing countries. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;25(5):353–358. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0000000000000392.

- Galhotra A, Sahu P. Challenges and solutions in implementing hearing screening program in India. Indian J Community Med. 2019;44(4):299–302. doi: 10.4103/ijcm.IJCM_73_19.

- Joint Committee on Infant Hearing Year 2019 position statement: principles and guidelines for early hearing detection and intervention programs. J Early Hear Detect Interven. 2019;4(2):1–44.

- Kamenov K, Chadha S. Methodological quality of clinical guidelines for universal newborn hearing screening. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2021;63(1):16–21. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.14694.

- Wen C, Zhao X, Li Y, et al. A systematic review of newborn and childhood hearing screening around the world: comparison and quality assessment of guidelines. BMC Pediatr. 2022;22(1):160. doi: 10.1186/s12887-022-03234-0.

- Fujian Provincial Health Department, & Fujian Federation of Persons with Disabilities. Implementation plan for hearing screening in Fujian Province. Ministry of Health in Fujian Province, No. 327, Document of Fujian Health Bureau; 2004. Available from: https://max.book118.com/html/2017/0214/91265268.shtm

- People’s Government of Hunan Province. Notice of the Ministry of Health on the issuance of the technical specification for the screening of newborn diseases; 2020. Available from: https://www.hunan.gov.cn/hnszf/xxgk/wjk/zcfgk/202007/t20200730_44d308fe-e86d-4f6b-8cd2-aa48b82b0ceb.html

- Moeller MP, White KR, Shisler L. Primary care physicians’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to newborn hearing screening. Pediatrics. 2006;118(4):1357–1370. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1008.

- Khan NB, Joseph L, Adhikari M. The hearing screening experiences and practices of primary health care nurses: indications for referral based on high-risk factors and community views about hearing loss. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2018;10(1):e1–e11. doi: 10.4102/phcfm.v10i1.1848.

- Malas M, Aboalfaraj A, Alamoudi H, et al. Pediatricians’ knowledge and attitude toward hearing loss and newborn hearing screening programs. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2022;161:111265. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2022.111265.

- Goedert MH, Moeller MP, White KR. Midwives’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to newborn hearing screening. J Midwife Womens Health. 2011;56(2):147–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-2011.2011.00026.x.

- Zaitoun M, Rawashdeh M, AlQudah S, et al. Knowledge and practice of hearing screening and hearing loss management among ear, nose, and throat physicians in Jordan. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;25(1):e98–e107. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1709112.

- Arnold CL, Davis TC, Humiston SG, et al. Infant hearing screening: stakeholder recommendations for parent-centered communication. Pediatrics. 2006;117(5 Pt 2):S341–S354. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2633N.

- Wall TC, Senicz E, Evans HH, et al. Hearing screening practices among a national sample of primary care pediatricians. Clin Pediatr. 2006;45(6):559–566. doi: 10.1177/0009922806290611.

- Colozza P, Anastasio AR. Screening, diagnosing and treating deafness: the knowledge and conduct of doctors serving in neonatology and/or pediatrics in a tertiary teaching hospital. Sao Paulo Med J. 2009;127(2):61–65. doi: 10.1590/S1516-31802009000200002.

- Ravi R, Gunjawate DR, Yerraguntla K, et al. A national survey of knowledge, attitude and practices among pediatricians towards newborn hearing screening in India. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;95:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2017.01.032.

- Chung YS, Oh SH, Park SK. Results of a government-supported newborn hearing screening pilot project in the 17 cities and provinces from 2014 to 2018 in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35(31):e251. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e251.

- The L: hearing loss: time for sound action. Lancet. 2017;390(10111):2414.

- Ministry of Health of the People’s Republic of China. Technical specifications for newborn hearing screening [EB/OL] [2010 edition, No. 96]; 2010 [cited 2010 Dec 1). Available from: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/fys/s3585/201012/170f29f0c5c54d298155631b4a510df0.shtml

- Dongyi H. Clinical audiology. Beijing (China): Peking Union Medical College Press; 2008.

- Wen C, Huang LH. Newborn hearing screening program in China: a narrative review of the issues in screening and management. Front Pediatr. 2023;11:1222324. doi: 10.3389/fped.2023.1222324.

- Edmond K, Chadha S, Hunnicutt C, et al. Effectiveness of universal newborn hearing screening: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health. 2022;12:12006. doi: 10.7189/jogh.12.12006.

- Olusanya BO, Luxon LM, Wirz SL. Benefits and challenges of newborn hearing screening for developing countries. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2004;68(3):287–305. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2003.10.015.

- Ravi R, Gunjawate DR, Yerraguntla K, et al. Systematic review of knowledge of, attitudes towards, and practices for newborn hearing screening among healthcare professionals. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;104:138–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2017.11.004.

- Xiaojing Y. Study on hearing screening of newborns – a case study in Tai’an, Shandong province. Electron J Clin Med Literature. 2017;4(3):583–584.

- Ismail AI, Abdul Majid AH, Zakaria MN, et al. Factors predicting health practitioners’ awareness of UNHS program in Malaysian non-public hospitals. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;109:78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2018.03.030.

- Mahmood Z, Dogar MR, Waheed A, et al. Screening programs for hearing assessment in newborns and children. Cureus. 2020;12(11):e11284. doi: 10.7759/cureus.11284.

- Ravi R, Gunjawate DR, Yerraguntla K, et al. Follow-up in newborn hearing screening – a systematic review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;90:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2016.08.016.

- Atherton KM, Poupore NS, Clemmens CS, et al. Sociodemographic factors affecting loss to follow-up after newborn hearing screening: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2023;168(6):1289–1300. doi: 10.1002/ohn.221.

- Fang BX, Cen JT, Yuan T, et al. Etiology of newborn hearing impairment in Guangdong province: 10-year experience with screening, diagnosis, and follow-up. World J Pediatr. 2020;16(3):305–313. doi: 10.1007/s12519-019-00325-4.