Abstract

Objectives

Mirror syndrome (MS) is a condition characterized by the presence of maternal, fetal, and placental edema and is reversible through delivery or pregnancy termination. As fetal hydrops itself may be amenable to treatment, we sought to determine outcomes for MS primarily managed by fetal therapy through a narrative review of the literature and cases managed at our fetal center.

Study design

PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar databases were searched through January 2024 using key words: mirror syndrome, Ballantyne’s syndrome, fetal hydrops, maternal hydrops, pseudotoxemia, triple edema, maternal recovery, fetal therapy, and resolution. Manuscripts describing primary management by fetal therapy that included maternal and fetal outcomes were identified. Clinical details of MS patients managed with fetal therapy at our center were also included for descriptive analysis.

Results

16 of 517 manuscripts (3.1%) described fetal therapy as the primary intended treatment in 17 patients. 3 patients managed at our center were included in the analysis. Among 20 patients undergoing primary fetal therapy for management of mirror syndrome, median gestational age of presentation was 24 weeks and 5 days gestation; predominant clinical findings were maternal edema (15/20), proteinuria (10/20), pulmonary edema (8/20), and hypertension (8/20); the primary laboratory abnormalities were anemia (8/20) and elevated creatinine or transaminases (5/20). Condition-specific fetal therapies led to resolution of hydrops in 17 (85%) cases and MS in 19 (95%) cases. The median time to hydrops resolution was 7.5 days and to resolution of mirror syndrome was 10 days. Fetal therapy prolonged pregnancy by a median of 10 weeks with a median gestational age of 35 weeks and 5 days at delivery. All women delivered for indications other than mirror syndrome and 19/20 fetuses survived.

Conclusion

In appropriately selected cases, MS often resolves after fetal therapy of hydrops allowing for safe pregnancy prolongation with good maternal and infant outcomes.

Introduction

Mirror syndrome (MS) was first described in 1892 by Dr. Ballantyne and is clinically characterized by the triad of maternal, placental, and fetal edema [Citation1,Citation2]. The maternal symptoms of edema, weight gain, hypertension, elevated liver enzymes, anemia, headache, and visual disturbances have a significant clinical overlap with preeclampsia [Citation3,Citation4]. Mirror syndrome has been described complicating approximately 0.02% of all pregnancies during the second and third trimester [Citation4]. Due to the clinical overlap with preeclampsia, however, the prevalence of mirror syndrome is likely underreported, especially since third trimester maternal symptoms are more likely to prompt delivery rather than a detailed diagnostic evaluation including fetal ultrasound. Although the exact cause for mirror syndrome is unknown, hydropic placenta is believed to produce elevated levels of sFlT1 [Citation5]. Mirror syndrome presents with similar maternal symptoms regardless of the underlying etiology of fetal hydrops. A wide range of fetal conditions leading to hydrops have been reported in patients presenting with mirror syndrome, including isoimmunization, hemoglobinopathies, twin-twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS), viral infections, fetal cardiomyopathies, supraventricular tachycardia, chylothorax, and placental chorioangioma [Citation3,Citation4,Citation6–8].

Delivery or termination of pregnancy leads to resolution of MS. Accordingly, these management approaches and the range of underlying fetal conditions leading to hydrops and MS have been the focuses in the literature, which is primarily limited to case reports [Citation4,Citation6,Citation8]. Although some causes of hydrops are prenatally reversible through fetal treatment, primary management of MS by treatment of the inciting fetal condition is less emphasized [Citation9,Citation10]. In cases managed with fetal therapy, the primary treatment goal is the resolution of hydrops through correction of the underlying fetal condition with the intent to improve fetal outcome [Citation11]. This management strategy would be appropriate for fetal hydrops caused by potentially treatable fetal conditions, in the setting of access to necessary treatment and safe management of maternal symptoms. This narrative review’s aim, including cases managed at our center, was to evaluate maternal and perinatal outcomes following in utero treatment of fetal hydrops, as a primary management strategy of mirror syndrome. We hypothesized that treatment of the underlying fetal condition resolves MS in a high proportion of cases allowing for pregnancy prolongation.

Methods

Eligibility criteria, information sources, search strategy

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board on 11 June 2020. An online search was conducted by two separate authors for articles published from inception through January 2024 using PubMed database, Embase, Web of Science, Scopus and Google Scholar. Studies were identified using the following.

Manually searched references from the included articles were also used if they did not already exist in the database search.

Study selection

A publication was considered eligible for inclusion if the primary management intention was treatment of the fetal condition, if details on fetal treatment were available, and if subsequent maternal and fetal outcomes were reported. Selective fetal reduction as the primary treatment in a twin pair was not considered if another life-preserving treatment option for the second twin would have been available. Studies were excluded if delivery was the primary management choice, if fetal demise occurred, or if the patient chose pregnancy termination because the aim of this review was to examine outcomes of cases managed with fetal therapy.

Data extraction and analysis

Variables collected included fetal diagnosis, gestational age at treatment, type of intervention, maternal symptoms at presentation, additional maternal treatment provided, time to resolution of hydrops, time to resolution of maternal symptoms, indication for delivery, gestational age at delivery, and fetal or neonatal outcome. The type of in utero treatment was noted. The analysis was descriptive.

Assessment of bias

The initial search was done in a standardized manner. To minimize bias, a second author did an additional separate search to ensure no relevant studies were excluded. All manuscripts from PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Scopus and Google Scholar that met inclusion criteria were selected. After duplicates were removed, manuscripts were then excluded if they did not address both fetal and maternal response to an in utero fetal intervention.

Results

Study selection

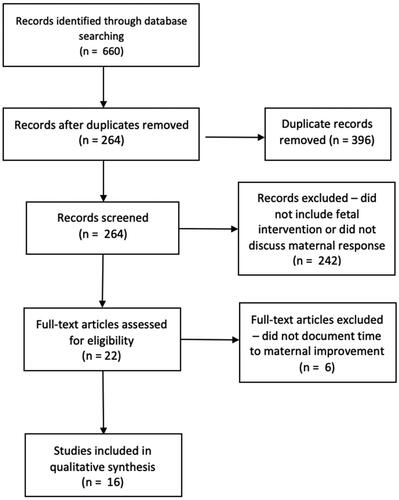

By searching PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Scopus and Google Scholar with the given keywords, 660 manuscripts were identified (). After duplicates were removed, 264 remained. These records were screened and all manuscripts that did not include a fetal intervention or discuss maternal response were excluded (242 records). The remaining 22 records had full text assessment for inclusion. After full text review, 6 additional manuscripts were excluded as they did not provide sufficient detail on maternal response including time to improvement, which left 16 reports that were eligible for inclusion describing the course of 17 patients. In addition, clinical characteristics of 3 cases managed at our institution were included for analysis, of which 1 has been previously published [Citation12].

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram for mirror syndrome search. illustrates the flow of study identification and selection. Initial search resulted in 660 manuscripts, which after removal of duplicates and those that did not include a fetal intervention or discuss maternal response, yielded 16 reports that were eligible for inclusion.

Study characteristics: cases managed at the Johns Hopkins Center for Fetal Therapy

Case 1

A 50-year-old gravida 4, para 3 presented at 25 weeks and 4 days with progressive edema and elevated liver enzymes with Aspartate Aminotransferase (AST) of 196 U/L and Alanine Transaminase (ALT) of 277 U/L. Her baseline systolic and diastolic blood pressures in the 120 and 60 mmHg range rose as high as 153/87 respectively. Ultrasound showed fetal hydrops, an amniotic fluid index of 28 cm and an elevated middle cerebral artery peak systolic velocity (MCA PSV) of 64.92 cm/s (1.78 Multiples of the Median (MoM)) suggesting fetal anemia. At initial blood sampling the fetal hemoglobin was 2.2 g/dL and required two sequential blood transfusions for correction. With these interventions, placental hydrops resolved but fetal hydrops did not. During the hospital course, maternal AST and ALT rose to 569 and 664 U/L, respectively and serum creatinine rose to 1.1 mg/dL. Pulmonary edema, clinically suspected and confirmed by chest x-ray, with maternal oxygen requirements up to 10 L/minute accompanied an elevated brain natriuretic peptide of 2800 pg/mL. Complete resolution of MS occurred after the second transfusion and the patient was discharged home asymptomatic on day nine. A female infant (birth weight 1730 grams, Apgar score 2, 2, 2 at 1, 5 and 10 min, respectively) was delivered by emergency cesarean section for placental abruption at 28 weeks and 2 days gestation (cord artery pH 7.37). Postnatally, the infant required repeat blood transfusion and exome genetic testing identified a PIEZO1 mutation. The infant was discharged home at 3 months of age ().

Table 1. Maternal mirror syndrome cases.

Case 2

A 33-year-old gravida 3, para 2 presented at 26 weeks and 4 days gestation with fetal hydrops and an elevated MCA PSV of 68.36 cm/s − 1.99 MoM due to suspected fetomaternal hemorrhage, confirmed on Maternal Kleihauer Betke testing. She underwent fetal blood transfusion increasing the initial fetal hemoglobin of 3.9–10.4 g/dL, followed by a second transfusion after two days increasing the opening hemoglobin of 7.9–16.3 g/dL. The patient developed dyspnea with radiographic evidence of pulmonary edema leading to maternal hypoxia with oxygen requirement of 10 L/minute. Baseline systolic and diastolic blood pressures in the 110 and 60 mmHg range rose as high as 149/97 mmHg, respectively. Pro-brain natriuretic peptide was elevated at 1234 pg/mL, and she had elevated liver enzymes to 73/99 U/L (AST/ALT). After the second transfusion, the patient’s clinical status started to improve, and she was discharged home on post-operative day five. Fetal hydrops resolved after one week. The patient delivered a female infant (birthweight 3380 grams, Apgar score 8 and 8 at 1 and 5 min, respectively) by uncomplicated vaginal delivery at 39 + 1 weeks. The infant did not require further therapy after birth ().

Case 3

A 26-year-old gravida 1, para 0 presented at 25 + 1 weeks with monochorionic-diamniotic twins with Stage 4 TTTS and coexisting twin anemia polycythemia sequence (TAPS) and underwent emergent fetoscopic laser ablation of placental vessels. The patient’s immediate post-operative course was complicated by pulmonary edema and associated hypoxia, with an oxygen requirement of 5 L/minute. Her baseline systolic and diastolic blood pressures in the 110 and 60 mmHg range rose as high as 148/88 mmHg respectively. She also developed an elevated creatinine of 1.1 mg/dL, elevated lactate dehydrogenase of 323 U/L, and liver enzymes of 55/39 U/L (AST/ALT). After laser, fetal hydrops and maternal status slowly improved over 5 days allowing discharge on post-operative day 7. She delivered vaginally at 35 weeks after premature rupture of membranes delivering male infants weighing 2200 grams with Apgars of 8 and 9 for both twins. The neonates required 12 days of neonatal care for prematurity and respiratory management ().

Study characteristics: cases from the literature

17 Cases were identified in the literature (). The majority of underlying fetal conditions were anemia (n = 8), followed by stage 4 TTTS (n = 4), fetal arrhythmia (n = 2), bilateral hydrothorax (n = 2), and fetal pelvic mass causing obstruction (n = 1). All of the patients received disease-specific treatment consisting of correction of the anemia by fetal transfusion, fetoscopic laser ablation of placental vessels, antiarrhythmic therapy, and peritoneal-amniotic or pleural-amniotic shunting, respectively.

Synthesis of results

In this series, the median gestational age of presentation was 24 + 5 weeks gestation with the predominant findings of maternal edema (15/20), proteinuria (10/20), pulmonary edema (8/20), and hypertension (8/20; ). Maternal laboratory abnormalities were anemia (8/20) and elevated creatinine or transaminases (5/20). The median time to resolution of hydrops was 7.5 days (range 1–35) and to resolution of mirror syndrome was 10 days (range 1.5–32). Fetal therapy prolonged pregnancy by a median of 10 weeks (3–16 weeks) with a median gestational age of 35 + 5 weeks at delivery (27 + 1 − 41 + 0 weeks’ gestation). All women delivered for indications other than mirror syndrome and all but one treated fetus survived ().

Table 2. Maternal and fetal clinical characteristics.

Discussion

While there are a variety of manuscripts on mirror syndrome, only a small fraction of reports focus on fetal treatment as the primary management strategy. Much of the literature instead focuses on recognition of the syndrome as a unique maternal condition, with most cases undergoing pregnancy termination or delivery for maternal indications as the primary treatment strategies [Citation6,Citation7,Citation13]. Cases identified by this review undergoing fetal treatment typically presented in the late second trimester, all with fetal diagnoses identified as being amenable to treatment. In this cohort, pregnant patients improved with fetal therapy, and ultimately were delivered for indications unrelated to their initial presentation. In fact, in 7 of the cases, fetuses were able to be delivered at full-term given in utero intervention. In addition, none of the patients had an adverse event related to the resolution of their mirror syndrome, which, to our knowledge, is the first time the implications of treatment of the fetus have been highlighted beyond case reports. Our data suggests that when a reversible fetal cause can be identified and treated, maternal symptoms and hydrops resolve in a high proportion of cases within 2 weeks. These observations provide reassurance that fetal treatment can be selected as the primary management approach in select cases of mirror syndrome.

A small body of recent literature has emerged highlighting the potential role for fetal therapy in appropriately selected cases with favorable outcomes associated with these interventions. Trad et al. published a review in 2022 regarding the diagnosis and management of mirror syndrome and underscored the role of fetal therapy in cases of surgical intervention on fetal sacrococcygeal teratoma, shunt placement, and in utero transfusion [Citation14]. Similarly, Chimenea et al. published a small case series in 2019 that highlighted the promising role of fetal therapy using shunt placement and in utero transfusion in treatment of fetal hydrops and resolution of MS [Citation15]. Our review adds to the limited existing literature and provides an important option for maternal and fetal benefit to appropriately selected patients beyond delivery or pregnancy termination. Taken together, the published literature and this report highlight the importance of prenatal access to a wide scope of treatment options because there are many underlying conditions that can lead to hydrops [Citation11]. This emphasizes the importance of early diagnosis of mirror syndrome and referral to a fetal center for expedited evaluation and treatment.

Resolution of mirror syndrome (19/20 cases) was 10% higher than resolution of hydrops (17/20 cases) in this cohort managed by fetal therapy as the primary treatment modality. In the two cases where hydrops did not resolve, the patient delivered a liveborn infant at 32 weeks’ gestation and in the other, there was a neonatal demise after delivery at 30 weeks’ gestation. The reasoning for this discrepancy remains unclear and additional information is required to determine what signs and symptoms herald resolution of fetal hydrops and MS. Understanding this will help to monitor disease progression. This information could be obtained through the creation of a large international registry with a focus on specific markers of successful treatment of MS.

Our study has several strengths and limitations. Limitations include the small sample size, the lack of standardized assessment of patients across the publications included, and the potential for publication bias. Fetal hydrops and subsequent mirror syndrome are rare and heterogenous in presentation, therefore the accumulation of large numbers of cases that are similarly documented is difficult. The creation of a multi-center registry with standardized reporting and collection of uniform data could potentially address this and answer important diagnostic and management questions. These questions include the key maternal parameters that define disease severity and herald improvement, the determinants and indicators of maternal resolution after initiation of fetal therapy, and the overall success rate with fetal treatment stratified by the underlying condition. In addition, this would help minimize publication bias, as cases of unsuccessful fetal therapy are likely underrepresented in the literature. A notable strength of this study is that it collates cases with a specific emphasis on the relationship between fetal treatment and resolution of maternal disease. While it has been demonstrated that fetal and placental edema can lead to MS, the converse has not been emphasized to the same degree. This finding is especially important for providers when a patient has symptoms of pre-eclampsia or mirror syndrome, as this should prompt a detailed fetal evaluation for the presence of and potential treatment options for hydrops.

Overall, our study indicates that in cases of mirror syndrome, evaluation for a possible underlying fetal condition is essential as it may identify fetal hydrops amenable to treatment. If disease-specific treatment for fetal hydrops can be offered, and the maternal condition can be safely managed with supportive therapy, fetal therapy as the primary treatment has the potential to produce favorable outcomes in terms of pregnancy prolongation and neonatal survival.

Acknowledgements

This research did not receive a grant from any funding agency.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Kaiser IH. Ballantyne and triple edema. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1971;110(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(71)90226-2.

- Hirata G, Aoki S, Sakamaki K, et al. Clinical characteristics of mirror syndrome: a comparison of 10 cases of mirror syndrome with non-mirror syndrome fetal hydrops cases. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;29(16):2630–2634.

- Yeom W, Paik ES, An JJ, et al. Clinical characteristics and perinatal outcome of fetal hydrops. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2015;58(2):90–97. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2015.58.2.90.

- Jung E, Romero R, Yeo L, et al. The etiology of preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;226(2S):S844–S866. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.11.1356.

- Stepan H, Faber R. Elevated sFlt1 level and preeclampsia with parvovirus-induced hydrops. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(17):1857–1858. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc052721.

- Allarakia S, Khayat HA, Karami MM, et al. Characteristics and management of mirror syndrome: a systematic review (1956–2016). J Perinat Med. 2017;45(9):1013–1021.

- Braun T, Brauer M, Fuchs I, et al. Mirror syndrome: a systematic review of fetal associated conditions, maternal presentation and perinatal outcome. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2010;27(4):191–203. doi: 10.1159/000305096.

- Duthie SJ, Walkinshaw SA. Parvovirus associated fetal hydrops: reversal of pregnancy induced proteinuric hypertension by in utero fetal transfusion. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1995;102(12):1011–1013. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1995.tb10913.x.

- Matsubara M, Nakata M, Murata S, et al. Resolution of mirror syndrome after successful fetoscopic laser photocoagulation of communicating placental vessels in severe twin-twin transfusion syndrome. Prenat Diagn. 2008;28(12):1167–1168. doi: 10.1002/pd.2128.

- Moon-Grady AJ, Baschat A, Cass D, et al. Fetal treatment 2017: the evolution of fetal therapy centers – a joint opinion from the International Fetal Medicine and Surgical Society (IFMSS) and the North American Fetal Therapy Network (NAFTNet). Fetal Diagn Ther. 2017;42(4):241–248. doi: 10.1159/000475929.

- Baschat AA, Blackwell SB, Chatterjee D, et al. Care levels for fetal therapy centers. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139(6):1027–1042. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004793.

- Christino Luiz MF, Baschat AA, Delp C, et al. Massive fetomaternal hemorrhage remote from term: favorable outcome after fetal resuscitation and conservative management. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2019;45(5):361–364. doi: 10.1159/000492750.

- Biswas S, Gomez J, Horgan R, et al. Mirror syndrome: a systematic literature review. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2023;5(9):101067. doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2023.101067.

- Teles Abrao Trad A, Czeresnia R, Elrefaei A, et al. What do we know about the diagnosis and management of mirror syndrome? J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022;35(20):4022–4027. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2020.1844656.

- Chimenea A, García-Díaz L, Calderón AM, et al. Resolution of maternal mirror syndrome after successful fetal intrauterine therapy: a case series. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):85. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-1718-0.