ABSTRACT

This paper presents a comparative analysis of the linguistic landscapes (LL) of two distinct ethnic areas in Shin-Ōkubo, Japan: Koreatown and Islamic Street. By paying particular attention to the difference in the formation of the two immigrant communities, this study aims to better understand various functions of language on signage and their impact on socio-cultural interactions between immigrants and the host society. The findings reveal distinct functions of languages in the LLs, showcasing their significance to the dynamic process of immigrant community formation. In Koreatown, a major centre of Korean culture consumption among the Japanese, the symbolic use of Korean asserts authenticity and offers Japanese tourists an exotic experience. This creates a cohesive space of commodification, vitalising the area in harmony with the local host community. In contrast, Islamic Street represents a multifaceted space shaped by a diverse array of languages and scripts, reflecting its recent emergence of ethnolinguistic vitality. The LL of Islamic Street, characterised by the informational use of language that caters to the daily needs and transnational practices of immigrants, reflects and fosters their social and cultural distance from the host society.

Introduction

While the ethnolinguistic homogeneity that was once viewed as the national ideology of Japan has been gradually fading, Japan, especially since the Japanese economic boom of the 1980s, has been transforming into an even more multilingual and multicultural society (Gottlieb, Citation2018; Shoji, Citation2019). According to the Immigration Services Agency, foreign residents from various countries reached 3 million as of 2022, accounting for 2.4% of the total population (125 million), with a one-million increase from 2012. The influx of migrants speaking various languages has significantly impacted language use across various contexts, including languages inscribed in public signage.

This study investigates the linguistic landscape of Shin-Ōkubo, an inner-city area of Tokyo, conducting a comparative analysis of ethnic businesses in two contrasting areas that are informally referred to as Koreatown and Islamic Street. The aim of this study is not only to showcase Japan’s increasing multilingualism with a growing number of different languages in public spaces, but also to examine the variation in the functions of languages on signage according to the diverse characteristics of immigrant communities, including their interactions with the host society. Shin-Ōkubo refers to the vicinity surrounding JR Shin-Ōkubo Station in Shinjuku, Tokyo, located adjacent to Kabukicho, one of the largest downtowns in Japan. As of December 2022, foreign residents in Shinjuku account for 11.6% of the total population (40,386/346,835), the highest among the central districts in Tokyo, and the proportion of foreign residents in Shin-Ōkubo is as high as 35.4% (7,005/19,792).Footnote1 summarises the demographic information of foreign residents in Shinjuku, indicating the Chinese residents are the largest group, followed by Koreans.

Table 1. Top 5 populations of foreign residents in Shinjuku, as of December 2022.

By focusing on an area with a significant immigrant population, we aim to better understand the diverse functions of language on signage and their impact on socio-cultural interactions between immigrants and the host society. As will be discussed later, Koreatown, with its strong cultural attractivity, serves as a major centre of Korean culture consumption with extensive interaction with the host society. In contrast, Islamic Street is a more recent, multi-ethnic area with limited cultural appeal to the host society, where ethnic businesses primarily target their own nationalities to facilitate transnational practices, resulting in a certain level of independence from the host society.

Research on linguistic landscape (hereafter LL) has delved into the multilingual and multicultural aspects of society, including studies on languages of immigrants (e.g. Buckingham, Citation2019; Karolak, Citation2022; Yao & Gruba, Citation2020). Regarding the functions of immigrant languages in the LL, one of the characteristics discussed in the literature, particularly relevant to Koreatown in our study, is the commodification of language (Leeman & Modan, Citation2009). Other than its informational role in conveying a message, such use of language serves a symbolic function as part of the ideological representation of space, transforming the area into a commodity. For example, Leeman and Modan (Citation2009) argue that Chinese signs in Washington D.C.’s Chinatown have been turned into a commodified display of ethnicity, facilitating an exotic experience for tourists.Footnote2 In a similar vein, concerning LL and tourism, Nie and Yao (Citation2022) investigated the use of Dongba script in the LL of Lijiang, China, and argued that the increasing visibility and prominence of the script reflect a shift in tourism stakeholders’ attitudes towards linguistic commodification, with Dongba language and culture packaged for tourist consumption.

Research on LL has also explored other semiotic modes such as images and architectural elements, referred to as semiotic landscape (Jaworski & Thurlow, Citation2010). For example, studies of Chinese ethnic enclaves have revealed a frequent use of semiotic modes other than the language to reinforce Chineseness of the space, including the colour red symbolising good luck and good fortune in Chinese culture (Xu & Wang, Citation2021, p. 185) and traditional Chinese architectures such as archways (Lee & Lou, Citation2019). In that sense, it has been argued that the use of languages and semiotic resources can visually aid in demarcating ethnic communities as identifiable areas (Amos, Citation2016; Lee & Lou, Citation2019; Zhao, Citation2021). The present study will also refer to semiotic and material resources, discussing how they shape the respective immigrant communities in conjunction with languages on signage.

Regarding the use of foreign languages in the LL of Japan, Backhaus (Citation2006), from a quantitative perspective, revealed that, while English was ubiquitous, other foreign languages accounted for less than 10% of the total of multilingual signs investigated in Tokyo. In the literature, the predominant use of English on signs in Japan is said to serve two purposes: an informational function for a broad international readership, and a symbolic function for both a foreign and a Japanese readership that conveys modernity and globalisation (Backhaus, Citation2006; Rowland, Citation2016). The present study will report that English was primarily used for informational purposes in Islamic Street, whereas the symbolic use of English was also found in Koreatown.

Regarding studies on LL of immigrant communities in Japan, for instance, Nambu (Citation2021) investigated the use of Brazilian Portuguese in Japanese-Brazilian communities as return migrants and highlighted that one of the areas incorporates its use for commodification to assist the revitalisation of the town. Suzuki (Citation2022) examined the use of Chinese in the LL of Chinatown in Yokohama, a well-established tourist destination where more than 90% of visitors are Japanese. Suzuki concludes that Chinese on signage serves as a medium for tourists’ identification of the space, indicating a strong affinity between tourism and LL with the language functioning as a resource for revitalising the area. Backhaus (Citation2010) investigated foreign languages used on signs in Tokyo and identified a prominent use of Korean on store signs in Shin-Ōkubo, our research site, although only a few signs in Korean by public authorities were found. Backhaus (Citation2010) also identified Korean-monolingual signs in the area, arguing that such use is informational in serving a Korean-speaking audience and is thus indexical of the local Korean community. Besides the informational function, we will highlight an extensive symbolic use of Korean in Koreatown, reflecting the recent rise of the K-pop boom and showcasing the commodification of the language as a vital component in providing a holistic and exotic experience to Japanese tourists in Koreatown.

Regarding the use of Korean in the LL of Korean communities in Japan, Kim (Citation2009) paid particular attention to a diachronic change in the use of scripts on signage. Kim (Citation2009) noted that, while the use of Hangul script on signs is prevalent in communities of recently arrived immigrants (often referred to as ‘newcomers’), communities of pre-war immigrants (‘oldcomers’) typically use Japanese scripts to transliterate Korean on signs. Kim (Citation2009) also argues that, in recent years, with the influx of newcomers into oldcomer communities, the use of Hangul script has become more common. As will be discussed in the next section, the different script choices on signage underscore a socio-historical gap between oldcomers and newcomers, reflecting the social changes surrounding them, including a shift away from social pressure for oldcomers to master the Japanese language and assimilate into Japanese society (see also Fukumoto, Citation2021).

Koreatown and Islamic Street in Shin-Ōkubo

Shin-Ōkubo saw a rapid increase in the number of foreign residents in the late 1980s, followed by the emergence of ethnic business facilities in the 1990s (Ono, Citation2020). Korean residents and businesses became especially concentrated in this area, leading to the formation of Koreatown as a community of Korean newcomers (Fukumoto, Citation2021). Initially, until the early 1990s, Korean businesses in the area mainly targeted Korean residents, including international calling card sales and international money transfer companies (Kim, Citation2020), which Vertovec (Citation2009) identifies as representative transnational practices. Gradually, the area became known for authentic Korean cuisine among the Japanese, and the Korean culture boom in the early 2000s, fuelled by events such as the soccer world cup jointly hosted by Japan and Korea in 2002 and the rise of Korean dramas, transformed the area into a hub for K-pop consumption among Japanese fans (Murohashi, Citation2020). Shifting away from businesses to assist transnational practices, the area has since been established as a tourist destination, with many Korean stores selling Korean goods and cosmetics (Kim, Citation2020).

Phillips and Baudinette (Citation2022) conducted an ethnographic study in Shin-Ōkubo and revealed how K-pop culture consumption shapes the Koreatown’s cityscape, such as K-pop music being played at many storefronts that sell K-pop idol goods as part of the soundscape. In particular, they argue that K-pop has been tied to young Japanese women’s consumer culture via Shin-Ōkubo, which caters to their needs, such as offering Korean cosmetics and Korean idol goods (see also Fukumoto, Citation2020). The present study will contribute to the understanding of the formation of Koreatown by highlighting how linguistic and non-linguistic objects, such as Hangul script on store signs and posters of K-pop idols at storefronts, offer Japanese visitors a unique experience in the commodified space.

Note that the current Koreatown in Shin-Ōkubo, shaped by Korean cultural power, emerged in the context of the long history of Korean immigrants in Japan. Koreans were the largest ethnic group in Japan during WWII with a population of 2.4 million, comparable to the entire foreign population today, until overtaken by the Chinese in 2007 (Fukumoto, Citation2021; Ishikawa, Citation2021). Despite the gradual decrease in the number of Korean immigrants since then, oldcomer Korean communities across Japan have increased the familiarity with Korean culture among the Japanese, laying the foundation for the development of Koreatown in Shin-Ōkubo. Another key aspect to understand Koreatown and its LL is the local Japanese business community, which has played a significant role in promoting Korean culture as the primary resource for vitalising the area. Kim (Citation2020) noted that many Korean stores in the area have joined the Shin-Ōkubo shopping district association led by Japanese locals, and the association has incorporated Korean cultural power to invigorate the area.

Although Shin-Ōkubo is mostly known as Koreatown, located on the east side of Shin-Ōkubo station, there is a growing presence of businesses from other ethnic groups in recent years. In particular, a small district on the west side of Shin-Ōkubo station has become known among the Japanese as ‘Islamic Street’. The area earned this name due to the presence of Muslim-related facilities such as a mosque. The area serves as home to a diverse range of ethnic businesses, mainly halal food stores, including those of India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Myanmar, and Nepal (Ono, Citation2020). Although called ‘Islamic’, not all stores are owned by Muslims. Stores owned by non-Muslims gather in this area due to the commonality in food culture, offering common products to their own and other nationalities. Therefore, collectively referring to the area as ‘Islamic Street’ (Isuramu Yokochō in Japanese) underscores the host society’s lack of recognition of the diversity present within the community. As will be discussed later, such recognition reflects the distance between the host society and the immigrants in the area, and also influences how immigrants view themselves and engage with the host society.

In contrast to Koreatown, Islamic Street is filled with transnational practices. For instance, many halal stores cater to specific needs of their respective nationalities, including discounted flight tickets to their home countries and international calling cards. The presence of international money transfer agencies that target immigrants is one of the unique characteristics of the area (Ono, Citation2020). These representative transnational practices exemplify the relative independence of immigrants’ businesses in Islamic Street from the host society. Furthermore, unlike businesses in Koreatown, those in Islamic Street are less engaged in working together with the Shin-Ōkubo shopping district association to vitalise the area.

The distinctive characteristics of the two areas discussed above signify the varying degrees of their socio-cultural adaptation, particularly concerning the extent of communication and interaction between immigrants and the host society, which is key for ‘cross-cultural adaptation’ (Kim, Citation2001). For instance, the significant presence of Korean cultural attractions in Japan, on top of the long history of Korean immigrants, facilitates such adaptation; the incorporation of cultural commodification by Korean businesses, with a focus on K-pop and Korean cosmetics and fashion, demonstrates their accommodation to the Japanese clientele’s specific needs, thereby enhancing communication with, and adaptation to, the host society. On the contrary, the same level of adaptation is not observed in Islamic Street. Our study highlights how the distinct functions of language use on signage in the two areas both mirror and further foster these differences within the two immigrant communities.

Methodology

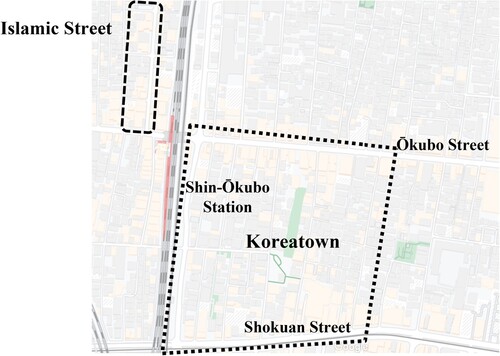

Building on the discussions in the previous sections, we draw attention to language use and script choice on signs in Shin-Ōkubo, as well as the use of images and other semiotic resources. As marked on the map of Shin-Ōkubo in , Koreatown is located between Ōkubo street to the north and Shokuan street to the south, while Islamic Street refers to the area centred on the street adjacent to the west of Shin-Ōkubo station.

We conducted fieldwork in Shin-Ōkubo in 2022, centred on the two areas marked on the map in . We collected photographs of signs for ethnic businesses, such as restaurants, that contain foreign languages, excluding temporary notes posted at storefronts, supplemented by administrative signs to provide additional contextual information. This focus aligns with this study’s aim of scrutinising varied forms of immigrant communities in the areas, rather than discussing government policies through investigating signs by public authorities. With the limited presence of foreign languages other than English on signage (Backhaus, Citation2006), the current study focuses on examining how individual languages are used in different manners, rather than identifying which language is more frequently used in the given area. Therefore, to facilitate a more-in-depth understanding of the LLs, this study adopted a qualitative approach to identify and discuss noteworthy trends according to the unique characteristics of the immigrant communities. The data contains a total of 166 signs, and each sign in the data was coded for its photographed location, language(s) contained, relationship between the languages (e.g. mutual translation, transliteration), type of semiotic resources along with the language use, and genre (e.g. type of business). When more than one language was identified on a sign, their relative prominence was taken into consideration in terms of visual characteristics of the text such as font size and colour contrast (Scollon & Scollon, Citation2003). Genre information was supplementarily used since the use of linguistic and non-linguistic materials may differ depending on the authorship and intended readership (Androutsopoulos & Chowchong, Citation2021; Nambu, Citation2021; Pietikäinen et al., Citation2011).

Furthermore, we incorporated our field notes and data from life history interviews with two immigrant owners of ethnic businesses in Islamic Street, which were originally conducted as part of a separate project. Where necessary, we referred to websites of the stores to provide further context on the use of languages and semiotic resources on signage.

Prior to the analysis in the next section, we first describe the use of language on signs by public authorities to provide the contextual background for the languages of the respective immigrants in Shin-Ōkubo. As mentioned earlier, the use of foreign languages other than English is relatively limited in Japan. In our research area, signs by public authorities are primarily monolingual Japanese or bilingual Japanese-English, consistent with the previous report by Backhaus (Citation2010). As the Tokyo Metropolitan government recommends prioritising the use of English, Chinese, and Korean on public signs in this order, which reflects the number of foreign residents and tourists in Tokyo (Gottlieb, Citation2018), there are multilingual signs showing this arrangement (a). However, we also observed signs where Korean is more prominent than Chinese (b) and signs with Korean but no Chinese (c). Since the number of Chinese residents outweighs the number of Koreans in Shinjuku, as shown in , the deviation from the government’s recommendation is not due to the demographics but may be a manifestation of the area’s unique characteristics as Koreatown. In the Islamic Street area, no languages other than the four languages mentioned above were found on signs by public authorities.

Figure 2. Signs by public authorities in Shin-Ōkubo (sign installer noted at the bottom of each sign). (a): Sign by the Shinjuku education committee; (b): Sign by the Shinjuku government; (c): Sign by the Shinjuku police department.

In what follows, we will analyse the data obtained in Koreatown, followed by the analysis of Islamic Street, to compare how linguistic and non-linguistic objects shape the two distinct communities that constitute the heterogeneous place: Koreatown, a well-established place of commodification serving Japanese tourists, and Islamic Street, a newly emerging ethnically mixed place that caters to the immigrants’ daily needs and transnational practices.

Koreatown as an established tourist destination

Upon arrival at the entrance to Koreatown in front of Shin-Ōkubo station, one can see a large Korean flag paired with a Japanese flag on the building on the corner of Ōkubo street (). The building, which houses a department store selling Korean goods, has been a symbol of Koreatown since 2005. The installation of the paired flags in 2005 can be interpreted as symbolising the emerging relationship between the two nations in the context of the soccer world cup jointly hosted by Japan and Korea in 2002 and the Korean drama boom in 2003. The presence of the large flag ornament in the area defines the space and serves as a landmark to direct visitors to Koreatown, much like traditional archways in Chinatown (Lee & Lou, Citation2019).

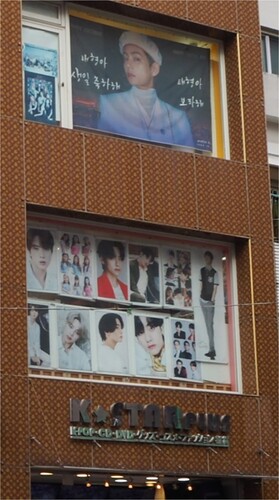

However, unlike Chinatowns, with their traditional architectural elements such as archways reinforcing Chineseness, there are no architectural representations of Korean culture that define the space. Rather, what lies at the centre of Koreatown in Shin-Ōkubo is a manifestation of contemporary consumer culture, catering not only to consumers of the traditional Korean food culture but also to Korean idol fandom and Korean cosmetic and fashion clientele. One of the most conspicuous items that marks the place as identifiable as Koreatown is Korean idol posters, with some of them being as large as a whole shop window as shown in , which is a K-pop idol goods store.

Phillips and Baudinette (Citation2022) reported that Japanese young women, who consist of the majority of the visitors, come to this area and take pictures of Korean idol posters as a fandom practice. Korean idol posters were not only found at the storefronts selling Korean idol goods (), but also at Korean cosmetics stores and restaurants, capitalising on the K-pop popularity and fandom practices. For example, the Korean cosmetics store in a displays a large panel of a K-pop idol promoting a Korean product, and the Korean restaurant in b exhibits pictures of K-pop idols introducing the restaurant’s cuisine in its storefront.

Figure 5. K-pop idol posters at non-K-pop goods storefronts. (a) Korean cosmetic store; (b) Korean restaurant

In such materiality of Koreatown in Shin-Ōkubo, the emplacement of Korean texts also reflects Korean culture consumption, offering visitors a unique experience through commodification of the language. Regarding script choice for Korean, it can be written in Hangul, Hanja (a Korean writing system using Chinese characters), or transliteration into Roman alphabet or Japanese (Kata)Kana. Among such choices, Koreatown in Shin-Ōkubo was notable for its abundant use of Hangul script in the LL. exemplifies this case, as the food stand name is written in Hangul, while the Japanese Katakana, in a smaller size below Hangul, serves as a transliteration of the product name for Japanese customers. The choice of Hangul can be considered reasonable, as it asserts Koreanness more strongly than each of the other script options. Given that most visitors in this area are Japanese attracted by Korean idols, cosmetics, and fashion, this demographic is considered the primary target of the authenticity expressed through the signs.

In Koreatown, the symbolic use of Hangul script extends beyond Korean-related businesses. shows a sign by a chain discount store that is not of Korean origin, but where Hangul script is displayed above the smaller Japanese text. Considering that other stores of the same chain in different areas do not use Hangul script, the large Hangul text can be interpreted as a deliberate strategy to capitalise on the prevailing Korean consumption culture trend in the area, representing a commodification of the language.

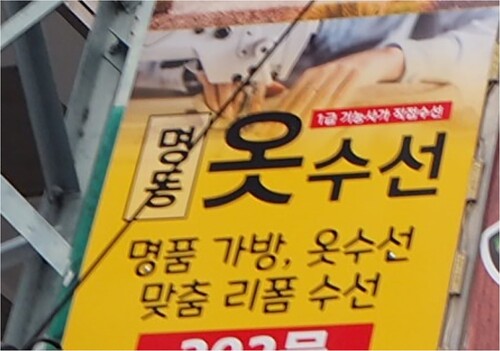

Alongside the predominant symbolic use of Korean on signage, there were also occasional instances of informational monolingual Korean business signs specifically targeting local Korean residents. is such an example, displaying the Hangul text ‘bags and clothing repair’. Considering the nature of the business, this sign is informational targeting a Korean readership, as it is less likely to attract Japanese tourists who visit Koreatown for cultural experiences. Such informational monolingual Korean signs were typically found on side streets and tended to be smaller in size compared to symbolic Korean signs designed for Japanese tourists.

Korean also appears in Roman characters as a transliteration. For example, the cafe sign in is written in large Roman characters alongside its smaller, less prominent Hangul counterpart. While this may appeal to a general readership, it also holds a symbolic interpretation that, much unlike Katakana, conveys modernness to Japanese (Backhaus, Citation2006; Rowland, Citation2016), who constitute the majority of visitors to Koreatown. In , there is a spelling error: ‘NAMCHINI’ on the main store sign is misspelled as ‘NAMHCINI’ at the bottom of the same sign, further supporting the interpretation that the presentation of Roman characters matters more than the content. The symbolic appeal aligns with the business theme, targeting the youth generation that forms the core of Korean culture and K-pop fandom (Phillips & Baudinette, Citation2022). This observation is further supported by monolingual English signs found at Korean stores, such as the Korean dessert chain store in a and the Korean clothing store in b. In these two examples, there are no visual cues on the storefronts that explicitly indicate them as Korean businesses. However, it is worth noting that their websites do identify them as Korean, and also prominently showcase pictures and videos of young Japanese women enjoying their foods and products, indicating that this particular demographic is their primary target audience.Footnote3 The youth generation tied to Koreatown has been proven to be actively engaged in social media, enabling them to easily recognise and locate Korean stores through their interactions and engagements on online platforms. For instance, Fukumoto (Citation2020) conducted a survey in Koreatown in Osaka and found that, in contrast to the participants in their 30s and older, a significant majority of younger participants use Instagram and YouTube to engage with Korean culture. Fukumoto (Citation2020) also noted that many younger individuals upload photos taken in Koreatown to social media. In these cultural contexts, the monolingual English signs for Korean stores can be interpreted as symbolically appealing to this demographic, exemplifying that the marketing in Koreatown plays an important role in shaping the LL.

Islamic Street as a newly emerged ethnic area

In contrast to Koreatown, where the symbolic use of Korean on signs creates a cohesive space of commodification, Islamic Street, as an ethnically mixed small area, exhibits the informational use of various languages on signs that manifest the immigrants’ daily needs and transnational practices. In other words, the LL of Islamic Street represents a recent emergence of ethnolinguistic vitality of the respective ethnic groups in the area. For example, there is Bengali in Bengali script on the sign of a halal store run by a Bangladeshi owner (), as well as Urdu in Urdu script by a Pakistani owner (), and Nepalese in Devanagari script by a Nepalese owner ().

The sign in exemplifies how the store facilitates transnational practices by offering international calling cards. During our interview with the Nepalese owner of the halal food store, he explained that even though he is not Muslim, he decided to open the halal food store in this area where there are several other halal stores, due to its convenience for other Nepalese, since many ingredients for Nepalese cuisine in Japan can only be purchased at halal food stores. Therefore, the commonality in food culture contributes to the diversity in the LL of Islamic Street.

In the examples shown in , English is prominently displayed on all of the signs, accompanied occasionally by their respective languages presenting the same information. This is likely because halal food stores aim to attract not only speakers of the respective languages but also customers who share the same food culture. Another possible reason is that countries on the Asian subcontinent, such as India, due to their colonial past have a long history of English being widely spoken. The use of English is therefore considered informational rather than symbolic, especially given that the nature of these ethnic businesses is not centred around portraying a modern image targeting the youth generation. In addition, unlike the case of Koreatown, there are no instances of transliteration using Japanese or Roman script. This suggests that the use of their own languages is primarily informational, targeting their own nationalities.

Supporting this view, our interview data revealed that the use of their languages on signage serves to inform individuals of the same nationality about their services and to establish their stores as a hub for the ethnic community, rather than appealing to Japanese customers. For example, the Nepalese owner of the halal store mentioned that since he opened the store in 2008, he has served as a casual consultant to Nepalese immigrants who visit his store, offering advice on all aspects of their lives. Furthermore, the following comments highlight that his store’s primary target is not the Japanese: ‘To the Japanese, our store is like a ‘museum’. It’s more of a place for them to observe rather than to buy products. It’s a spice museum, a showcase for ethnic cuisine products’ (interview conducted in Japanese, translated by the authors). Considering this, the use of Nepalese on the store sign, especially in conjunction with the Nepalese flag alongside (), targets their own nationality, rather than aiming to attract Japanese customers. This interviewee, who is not Muslim, also mentioned that he prefers the term ‘Halal Street’ to ‘Islamic Street’. His remark illuminates the gap between how the Japanese perceive the ethnic businesses in the area and how the immigrants view their own identity. Furthermore, voices among immigrants in this area suggest that they feel a lack of acceptance from the Japanese community. In an interview with a successful Bangladeshi business owner, who operates several stores including a halal store and travel agency, he mentioned ‘Only few Japanese want to get close to us … I believe they don’t want us to be part of their (business) community. (They may be wondering) how we manage to become so successful here, considering we’re from a different country, and with our business thriving, (they might fear) we could even attract some of their customers … ’ (interview conducted in Japanese, translated by the authors). He also points out the difference in how foreign ethnic store owners display their products in stores, a practice he believes local Japanese store owners do not appreciate and perceive as disorganised.

The data and discussion above suggest that the LL of Islamic Street reflects more than just the multilingual and multicultural aspect of the area through the presence of diverse languages on signage. It further illuminates how the ethnic businesses interact with the host society, particularly featuring the social and cultural gap that leads to their business orientation being disconnected from the host society. Therefore, this analysis underscores the importance of LL in understanding the diverse processes of immigrant community formation.

Discussion

The comparative analysis of the two areas revealed contrasting characteristics of their LLs, highlighting the diversity in the use of foreign languages on signage and providing insights into the dynamic process of immigrant community formation.

In Koreatown, along with semiotic resources such as K-pop idol posters, Korean signs primarily serve to commodify the area and assert the authenticity of businesses within the context of K-pop culture consumption. Even a non-Korean chain store uses Hangul script on their sign to capitalise on the commodification of Korean language and culture. Such use of Hangul script by non-Korean businesses is also considered a manifestation of the social changes experienced by Korean immigrants in Japan, shifting away from assimilation into Japanese society in the past and towards leveraging the K-pop boom through the commodification of the language. Moreover, the dominance of the modern K-pop consumption culture in Koreatown may explain the absence of traditional Korean architectural materials and colours, which is in stark contrast with the abundance of traditional cultural elements in Chinatown (e.g. Suzuki, Citation2022; Xu & Wang, Citation2021). Furthermore, the symbolic use of monolingual English signs for Korean stores demonstrates that the marketing of Koreatown towards the youth generation as the core of the consumption culture, who obtain and distribute information through online platforms, plays an important role in shaping the LL.

In contrast to the LL of Koreatown, which revolves around the commodification of the language, the LL of Islamic Street, with its diverse range of languages and scripts, primarily serves an informational purpose. Supported by the interview data, it reflects that their ethnic businesses, with fewer cultural attractions to the host society, mainly cater to the immigrants’ daily needs and transnational practices. As Parzer and Huber (Citation2015) discuss, migrant businesses not only contribute to the economic and social development of urban neighbourhoods but also play a key role in symbolically transforming the areas through representations of ethnic and cultural diversity coded in various materials (Parzer & Huber, Citation2015, p. 1270). In a similar way, the linguistic diversity observed in the LL of ethnic businesses in Islamic Street manifests the ethnolinguistic vitality of the respective ethnic groups. Furthermore, the present study revealed the social and cultural distance between the immigrants in the area and the host society. In contrast to the LL of Koreatown that mirrors and promotes intensive socio-cultural interactions with the host society, the LL of Islamic Street manifests fewer interactions, suggesting a lesser extent of cross-cultural adaptation to the host society (Kim, Citation2001). The limited socio-cultural interaction as well as the absence of strong cultural appeals to the Japanese may be symbolised by the name ‘Islamic Street’ (Isuramu Yokochō in Japanese), since the label reflects how the host society perceives the area, which actually includes businesses that are not Muslim-owned.Footnote4 Relevant to the point, it is important to note that the mere presence of a language on signs does not necessarily increase the visibility or the recognition of a particular ethnic group in a given area (Grey, Citation2021). Instead of focusing solely on the presence and absence of a language on signage, this study provides insight into how the language use in the LLs both shapes and is shaped by the surroundings of each immigrant community; that is, LL serves as a manifestation and part of socio-cultural dynamics of immigrant communities including cultural power and varying degrees of interactions and adaptation to the host society. Therefore, this study demonstrates that exploring the complex interplay of such socio-cultural factors that influence the formation of immigrant communities contributes to a deeper understanding of their LLs and vice versa.

Conclusion

This paper presented a comparative study of the LLs of Koreatown and Islamic Street in Shin-Ōkubo, Tokyo. The findings revealed that the increasing multilingualism in Japan encompasses not only the growing presence of foreign languages in public spaces but also the heterogeneity of LLs of immigrant communities. The two LLs illuminate and encompass the socio-cultural dynamics in the formation of the respective immigrant communities. Characterised by symbolic language use, the LL of Koreatown contributes to the creation of the commodified space with extensive engagement with the host society, mirroring the K-pop culture consumption. Conversely, the LL of Islamic Street, with its informational language use, reflects and promotes a certain degree of independence and separateness from the host society.

The findings from the current study suggest that a comparative study of LLs across various immigrant communities in a given area may reveal varying patterns of immigrant community formation, highlighting different degrees of sociocultural interaction and adaptation to the host society. While the difference in the LLs of compared communities may not be immediately obvious to passers-by, semiotic resources, as well as other contextual information, can assist in interpreting the functions of languages on signs. This was evident in our study, which showcased how the surrounding semiotic resources, along with information obtained from interviews, indicate the various functions of immigrant languages and English, which are dependent on the nature of interaction between the immigrant communities and the host society. Future research could explore additional elements, such as physical materials of signs – whether wood, plastic, or other materials – and also conduct a comparative analysis of online spaces including SNS utilised by ethnic businesses. Such approaches would offer additional insights into their intended audiences, thus further enriching our understanding of the LL in question.

Ethics and consent

The study was approved by Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (Project number 38533).

Acknowledgements

We express our appreciation to Louisa Willoughby and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments on this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In this paper, the population of Shin-Ōkubo is defined as the sum of the populations of Hyakuninchō 1-chome and 2-chome and Ōkubo 1-chome and 2-chome, in accordance with the scholarly consensus (see Ono, Citation2020).

2 Leeman and Modan (Citation2009) point out that the function of languages on signs, whether symbolic or informational, partly relies on the audience’s comprehension. For example, while ethnic authenticity can be perceived by those unable to read the language, those who can read it are also able to interpret the information provided (Leeman & Modan, Citation2009, p. 351; also see Sharma, Citation2021).

3 https://www.cafe-binggo.com/, http://placjapan.com/, accessed 15 November 2022.

4 The name ‘Koreatown’ (Koria Taun in Japanese) is also a simplification, as the loanword koria, instead of kankoku (South Korea), fails to differentiate between North and South Korea.

References

- Amos, H. W. (2016). Chinatown by numbers: Defining an ethnic space by empirical linguistic landscape. Linguistic Landscape. An International Journal, 2(2), 127–156. https://doi.org/10.1075/ll.2.2.02amo

- Androutsopoulos, J., & Chowchong, A. (2021). Sign-genres, authentication, and emplacement: The signage of Thai restaurants in Hamburg, Germany. Linguistic Landscape. An International Journal, 7(2), 204–234. https://doi.org/10.1075/ll.20011.and

- Backhaus, P. (2006). Multilingualism in Tokyo: A look into the linguistic landscape. International Journal of Multilingualism, 3(1), 52–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790710608668385

- Backhaus, P. (2010). Multilingualism in Japanese public space: Reading the signs. Japanese Studies, 30(3), 359–372. https://doi.org/10.1080/10371397.2010.518598

- Buckingham, L. (2019). Migration and ethnic diversity reflected in the linguistic landscape of Costa Rica’s Central Valley. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 40(9), 759–773. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2018.1557666

- Fukumoto, T. (2020). Kanryū būmu ka deno ōsaka-ikuno koriataun no hen’yō: Esunikku taun no kachi to chiiki kasseika [Transformation of Koreatown in Ikuno, Osaka under the Korean Wave: Value of the ethnic town and its revitalization]. Geographical Space, 13(3), 231–251. https://doi.org/10.24586/jags.13.3_231

- Fukumoto, T. (2021). The contrasting enclaves between Korean oldcomers and newcomers. In Y. Ishikawa (Ed.), Ethnic enclaves in contemporary Japan (pp. 71–98). Springer.

- Gottlieb, N. (2018). Multilingual information for foreign residents in Japan: A survey of government initiatives. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 2018(251), 131–149. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijsl-2018-0007

- Grey, A. (2021). Perceptions of invisible Zhuang minority language in Linguistic Landscapes of the People’s Republic of China and implications for language policy. Linguistic Landscape. An International Journal, 7(3), 259–284. https://doi.org/10.1075/ll.20012.gre

- Ishikawa, Y. (2021). Introduction. In Y. Ishikawa (Ed.), Ethnic enclaves in contemporary Japan (pp. 1–16). Springer.

- Jaworski, A., & Thurlow, C. (2010). Introducing semiotic landscapes. In A. Jaworski, & C. Thurlow (Eds.), Semiotic landscapes: Language, image, space (pp. 187–205). Bloomsbury.

- Karolak, M. (2022). Linguistic landscape in a city of migrants: A study of Souk Naif and Dubai. International Journal of Multilingualism, 19(4), 605–629. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2020.1781132

- Kim, M. (2009). Gengo keikan ni okeru imin gengo no arawarekata: Korian komyuniti no gengo hen’yō o jirei ni [The occurrence of immigrant languages in the linguistic landscape: A case study of linguistic transformation in Korean communities]. In H. Shoji, P. Backhaus, & F. Coulmas (Eds.), Nihon no gengo keikan [Linguistic landscapes in Japan] (pp. 187–205). Sangensha.

- Kim, Y. (2020). Tokyo-to Shinjuku-ku ōkubo chiku ni okeru kankoku kei bijinesu no shūseki to chiiki kasseika: Chiiki shigen to shite no esunishiti to daitoshi no ‘machi’ no saihen [Concentration of Korean businesses and regional revitalization in the Ōkubo district of Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo: Ethnicity as a regional resource and the restructuring of ‘town’ in large city]. Annals of the Japan Association of Economic Geographers, 66(4), 279–298. https://doi.org/10.20592/jaeg.66.4_279

- Kim, Y. Y. (2001). Becoming intercultural: An integrative theory of communication and cross-cultural adaptation. Sage Publications.

- Lee, J. W., & Lou, J. J. (2019). The ordinary semiotic landscape of an unordinary place: Spatiotemporal disjunctures in Incheon's Chinatown. International Journal of Multilingualism, 16(2), 187–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2019.1575837

- Leeman, J., & Modan, G. (2009). Commodified language in Chinatown: A contextualised approach to linguistic landscape. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 13(3), 332–362. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9841.2009.00409.x

- Murohashi, H. (2020). Rupo shin ōkubo: Imin saizensen toshi o aruku [Report on Shin-Ōkubo: Walking in the city of immigration frontline]. Tatsumi Publishing.

- Nambu, S. (2021). Linguistic landscape of immigrants in Japan: A case study of Japanese Brazilian communities. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2021.2006200

- Nie, P., & Yao, X. (2022). Tourism, commodification of Dongba script and perceptions of the Naxi minority in the linguistic landscape of Lijiang: A diachronic perspective. Applied Linguistics Review, Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2021-0176

- Ono, M. (2020). Daitoshi Tokyo no ‘tabunka kūkan’ de ikiru hitobito: Shinjuku Ōkubo no 24jikan hoikuen no kiroku [Individuals in multicultural space in the Tokyo metropolis]. Harvest-sha.

- Parzer, M., & Huber, F. J. (2015). Migrant businesses and the symbolic transformation of urban neighborhoods: Towards a research agenda. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 39(6), 1270–1278. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12347

- Phillips, K., & Baudinette, T. (2022). Shin-Ōkubo as a feminine ‘K-pop space’: Gendering the geography of consumption of K-pop in Japan. Gender, Place & Culture, 29(1), 80–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2020.1857341

- Pietikäinen, S., Lane, P., Salo, H., & Laihiala-Kankainen, S. (2011). Frozen actions in the Arctic linguistic landscape: A nexus analysis of language processes in visual space. International Journal of Multilingualism, 8(4), 277–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2011.555553

- Rowland, L. (2016). English in the Japanese linguistic landscape: A motive analysis. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 37(1), 40–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2015.1029932

- Scollon, R., & Scollon, S. W. (2003). Discourses in place: Language in the material world. Routledge.

- Sharma, B. K. (2021). The scarf, language, and other semiotic assemblages in the formation of a new Chinatown. Applied Linguistics Review, 12(1), 65–91. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2019-0097

- Shoji, H. (2019). Japan as a multilingual society. In P. Heinrich, & Y. Ohara (Eds.), Routledge handbook of Japanese sociolinguistics (pp. 184–196). Routledge.

- Suzuki, Y. (2022). Commodification of culture and its value as a tourist resource: Drawing from the linguistic landscape of Yokohama Chinatown. Bulletin of the Institute for Humanities Research, 67, 121–136. The Institute for Humanities Research, Kanagawa University.

- Vertovec, S. (2009). Transnationalism. Routledge.

- Xu, S. Z., & Wang, W. (2021). Change and continuity in Hurstville’s Chinese restaurants: An ethnographic linguistic landscape study in Sydney. Linguistic Landscape. An International Journal, 7(2), 175–203. https://doi.org/10.1075/ll.20007.xu

- Yao, X., & Gruba, P. (2020). A layered investigation of Chinese in the linguistic landscape: A case study of Box Hill, Melbourne. Australian Review of Applied Linguistics, 43(3), 302–336. https://doi.org/10.1075/aral.18049.yao

- Zhao, F. (2021). Linguistic landscapes as discursive frame: Chinatown in Paris in the eyes of new Chinese migrants. Linguistic Landscape. An International Journal, 7(2), 235–257. https://doi.org/10.1075/ll.20009.zha