ABSTRACT

With multiple blue crises unfolding, momentum exists to develop and implement transformative marine governance approaches towards sustainable use of our oceans. Such approaches will only be transformative when they foster reflexive governance that questions and changes existing values and structures of power and governance. Yet, we lack understanding of how transformative marine governance change relates to reflexivity. This article takes an actor perspective and conceptualises reflexivity through three elements: (1) the trigger that leads to (2) processes of single, double and triple loop learning and reflection, and (3) the capacity to enact change. Building on the duality of structure and agency, we argue that reflexive actors are able to enact transformative change by changing their policy practices and the governance arrangements they are embedded in. These changes can in turn lead to political modernization, i.e. the structural transformation processes within the political domain of society. This will also result in changes across multiple governance arrangements. However, reflexivity is a process both enabled and constrained by existing power and governance structures, and does not happen automatically. We therefore conclude that reflexivity and transformation require deliberation, contestation and the capacity to learn and break through vested interest, discourses and power structures.

1. Introduction

This article forms the theoretical basis for the Special Issue on Reflexive Marine Governance. Following the editorial, it puts forward a first theoretical exploration of what reflexivity is and how it relates to transformative change of marine governance. It therefore contributes to the Special Issue’s aim to advance theory and research into reflexive marine governance to deal with complex sustainability issues within the marine domain. As the editorial also outlines, multiple blue crises are unfolding simultaneously, from record temperatures of ocean water in the summer of 2023 to increasing evidence of chemical and plastic pollution that endangers not just marine mammals and fish (and therefore also humans), but also the broader health of ocean ecosystems. As a response to these crises, the momentum to develop new governance approaches is growing as illustrated by the UN Decade for Ocean Science, the adopted 2023 High Seas Treaty to protect marine biodiversity and the negotiations for a global Plastics Treaty.

Scholars of reflexive (sustainability) governance argue, however, that in order to effectively deal with sustainability challenges, the very foundations of governance itself need to be called into question (Feindt & Weiland, Citation2018; J. Voß & Kemp, Citation2005). As experiences with new governance concepts and approaches such as Ecosystem-based Management, Marine Spatial Planning and Blue Economy show, they – despite being based on ideas around transformative change – do not automatically lead to transformative, systemic changes (Cisneros-Montemayor et al., Citation2019; Evans et al., Citation2023; Kelly et al., Citation2019; Van Leeuwen et al., Citation2014; Schutter et al., Citation2021). Transformative change refers to a system-wide reorganization across technological, economic and social factors, including paradigms, goals and values (Visseren-Hamakers et al., Citation2021). Integrated and transformational ocean governance approaches – such as the Blue Economy (a sustainable and equitable economic development model based on oceans, similar to the Green economy) and Marine Spatial Planning (a system of ‘zoning’ ocean spaces to manage multiple uses) have in practice, however, been co-opted by vested interests and technocratic approaches that lead to incremental change at best, and a loss of sovereign decision-making power at worst, for instance when legal and financial provisions lead to philanthropic organizations grabbing control over ocean resources (Flannery et al., Citation2016; Mallin & Barbesgaard, Citation2020; Voyer et al., Citation2018).

We argue that a potential reason why these new governance concepts and approaches have not achieved the transformative change that was originally envisaged is because they have been integrated within existing values, power and political systems. As such, we contend that we need a better understanding of actors’ reflexive capacities (or abilities) to not only learn, but also reorientate and redirect governance systems and processes to build new social, political, economic, environmental and scientific structures in order to implement truly transformational change (cf. Donati, Citation2010; Pickering, Citation2018). In addition to typologies of reflexive sustainability governance (e.g. Van Tatenhove, Citation2017), there is a need to further theorise the link between reflexivity as a capacity of actors to reflect and learn, and the process of systemic change of governance structures to deal with contemporary social, policy and sustainability challenges.

We take the marine domain to explore these theoretical links between reflexivity and transformative change, as the marine domain and therefore its governance, has distinct characteristics that relate to and amplify the complexity of sustainability governance. In addition to the interplay between soil (seabed), air and (salt) water, oceans have a strong interaction with the earth climate through the exchange of water, energy and carbon (Pörtner et al., Citation2019) as well as with human and non-human communities around the world (Steinberg, Citation2001). Moreover, oceans are made up of liquid ecosystems and resources connecting continents with fluid boundaries (Tafon et al., Citation2022). However, liquidity not only refers to the physical characteristics of seas, but also of maritime activities, such as the mobility of for example fishing and shipping (Van Tatenhove, Citation2022). Due to the liquidity and mobility of ecosystems, activities and resources, the marine governance architecture and history differ from land. First, the invisibility of maritime activities and resources complicates its governing. Second, due to the mismatch between marine ecosystem borders and territorial waters of nation states marine governance is multi-layered as it includes not only the local and national, but also transnational levels. Third, there are no property rights related to the ‘ownership’ of ocean spaces or resources (Steinberg, Citation2018). Finally, economic development, which accelerated on land since the 1950s, knows a much more recent expansion in the marine domain, notably since 1990s–2000s (Jouffray et al., Citation2020).

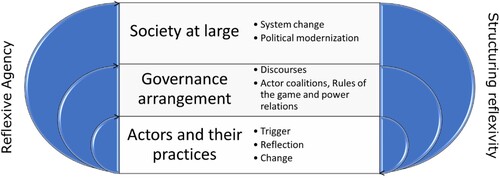

Recently, research within marine governance and Marine Spatial Planning focuses on transformative changes, power, inequalities and reflexivity (Flannery et al., Citation2016; Jay, Citation2022; Kelly et al., Citation2019; Tafon et al., Citation2022; Tatenhove, Citation2017). This article builds upon these insights from marine governance scholars, but aims to contribute to these by advancing the conceptual understanding of how reflexivity relates to transformative marine governance change. We do so by defining reflexivity as a capacity of agents that needs to be triggered to engage in a process of reflection, learning and change (section 2). In section 3, we argue that such reflections are processes of social learning. We then ask in section 4: How does reflexivity – and processes of social learning – relate to transformative marine governance change? We argue that it is through the interplay between agency and structure that we can start to understand how reflexivity of an actor translates into transformation at three levels: the interactions between actors in policy practices, the governance arrangement in which the interactions between actors take place and the wider institutional governance context (political, social and economic systems) in which this governance arrangement is embedded. We end this article with concluding in section 5 that reflexive actors are bounded actors, meaning that reflexivity is often curtailed by the political and institutional setting, making reflexivity and transformational change challenging to achieve.

2. Defining reflexivity

This section first discusses reflexivity in how it relates to ideas around reflexive modernization and risk society, before defining reflexivity in terms of the three elements of a trigger, social learning and capacity to change.

2.1. Reflexive modernization and reflexivity

Beck, Giddens and Lash (Beck et al., Citation1994) use the term reflexivity in relation to reflexive modernization and the risk society. The concept of a ‘risk society’ encapsulates a shift in the societal ethos, from one that was characterised by security and predictability associated with inherited traditions and entrenched cultural and social norms, to one which collectively identifies with an increasing dislocation, fragmentation, the breaking down of cultural norms and a growing sense of vulnerability to risk (Ekberg, Citation2007). The emergence of a risk society has been heightened by the mounting pressures on global sustainability, such as biodiversity loss, plastic and chemical pollution, and climate change. Risk society forces reflexivity, especially when confronted with the extent of the planetary crises we face, evidenced by extreme weather, pollution and biodiversity events. Beck defines reflexivity as self-confrontation; ‘reflexive modernization means self-confrontation with the effects of risk society that cannot be dealt with and assimilated in the system of industrial society (…)’ (Beck, Citation1994). Beck, however, was not interested in reflexivity as such, but rather emphasised reflexive modernization as a distinct phase in the modernization of society, one in which modern society transforms from modern to a late modern society. According to Beck (Citation2006) the transition to reflexive modernity brings with it the challenge of developing a new logic of action and decision, which no longer finds its orientation in the principle ‘either this or that’, but rather in the principle ‘this and that both’. The both/and principle means that the institutions of the first modernity are not replaced by reflexive modernity, but are still an integral part of it.

This turn to reflexivity, in response to a heightened understanding of the inherent risks embedded within modern society, ultimately drives reflection, debate and discussion around the questions of what societal transformation should look like. What aspects of modern society need to be transformed, who should be included in transformation and how is this best facilitated? A variety of responses to this question have been put forward as models through which the effects of the risk society might be addressed. For example, post-capitalist or degrowth agendas respond to the current planetary crises by calling for a transformative shift away from current patterns of growth and consumption (Hickel & Kallis, Citation2020; Schmelzer et al., Citation2022). Postcolonial writers respond to historic and current injustice by arguing for repatriation and reparations of Indigenous land and seas and decolonization of western approaches to governance which support and enable unsustainable and inequitable outcomes (Carter, Citation2018; Tuck & Yang, Citation2021). Feminist scholars challenge the rationalist and positivist scientific traditions which underpin modern governance structures and call for a move towards more ‘care-full’, relational and inclusive approaches (Plumwood, Citation1991). What is common across these writings is a call for radical shifts in the institutional frameworks that govern modern society.

In response to such increased attention for the transformation of society, we emphasise that there is a need for reflexive governance, which we define as a calling into question of how patterns and processes of governance themselves challenge the success of sustainable development (Beck, Citation2006; J. Voß & Kemp, Citation2005). Reflexive governance then is about how sites of reflexivity (reflexive arrangements) are situated within their broader socio-political context, including multiple arena’s, actors and forms of political communication (Hendriks & Grin, Citation2007). These sites of reflexivity are where current governance practices and structures are scrutinised, both in terms of how existing discourses and governance arrangements reproduce (un)sustainable outcomes and in terms of how governance structures and processes could facilitate reflexivity (Boström et al., Citation2017; Feindt & Weiland, Citation2018).

2.2. Elements of reflexivity

In this article, we focus on reflexivity to better understand the enabling and constraining conditions of long-term political and transformative change. This means centralizing the role of the agent and agency in conceptualizations of how societies and their political systems modernise. In general, agency refers to individual or group abilities (intentional or otherwise) to affect their environment (Giddens, Citation1984). In marine governance, an agent refers to all public and private actors who are (directly and indirectly) involved in steering and governing activities (on land and at sea) and their consequences for the marine environment. Which actors are involved and whose reflexivity is leading to transformative change is an empirical question depending on the specific maritime and marine activities and issues studied. This will be further elaborated in section 4.

For Archer (Citation2007) reflexivity is ‘the regular exercise of the mental ability shared by all normal people to consider themselves in relation to their social contexts and vice versa’. Following (Pickering, Citation2018), we see reflexivity consisting of three elements. The first is the process of self-confrontation when faced with unintended side effects that cannot be ignored (Beck, Citation2006; Pickering, Citation2018). The modern ‘risk society’ is an expression of multiple ways in which society is confronted with unintended consequences which can act as pathways to reflexivity. In a marine governance context, resource use conflicts, climate shocks, natural disasters and ecosystem or species collapse force attention to the efficacy of existing governing processes and conditions (Tafon et al., Citation2022). In this regard, reflexivity is (in part) reactive in that it occurs in response to an undesirable set of circumstances or unwanted change that act as a trigger for the second element of reflexivity, which is reflection and learning (Pickering, Citation2018). The third element is the actor’s capacity, i.e. capability, to respond to this reflection and learning, by reorientating and building new or changing existing social structures.

Reflexivity is therefore grounded in processes of reflection, which includes examining, learning and reforming practices based on incoming information. As such, information is a key resource for reflexivity (Boström et al., Citation2017; Toonen & Tatenhove, Citation2020). According to Donati (Citation2010, Citation2011), reflexivity should be understood as a social relation between ‘Ego’ and ‘Alter’ within a social context. He makes a distinction between personal, social and systemic reflexivity. Personal reflexivity is about an internal conversation (where Alter is Ego), social reflexivity refers to an interaction in which Alter is a different person and actors gain insights (learn) from the interaction. Systemic reflexivity refers to the socio-cultural structures and their interactive ‘parts’, with their powers and qualities (Donati, Citation2011). Reflexivity therefore refers to the ability of actors to turn or bend back on themselves (Hendriks & Grin, Citation2007). According to Archer (Citation2010) reflexivity depends upon a clear subject-object distinction, because it is ‘precluded by “central conflation”, where the properties and powers respective to structures and to agents are elided’. It refers to the ability of actors to recognise and reflect upon the governance contexts and social structure within which they operate and respond by making meaningful adjustments to their (institutional) circumstances and practices (Kamil et al., Citation2021).

Reflexivity is more than a reactive process (as suggested by Beck) that leads to self-confrontation; it is about reflection, learning and having the capacity for reorientation and redirection helping to build up new social structures (Donati, Citation2010). Reflexivity can be partial, i.e. a trigger does not have to lead to reflection and learning, and reflection and learning does not have to translate into an actual response. However, we propose that having the capacity to consider how one’s organizational and governance practices require change and acting upon it is a critical element for understanding the way in which reflexivity translates into transformative change. As Pickering (Citation2018) notes, reflexivity is a latent capacity that manifests itself periodically through shifts in values and (corresponding) practices. A practice is defined as ‘an ensemble of doings, sayings and things in a specific field of activity’ (Arts et al., Citation2014) – in this case governing oceans and their users. Whether or not organizational and policy practices and governance arrangements change as a result of reflexivity then becomes an empirical question.

In sum, we define reflexivity as the capability to engage in the cognitive process of dealing with incoming information in order to enact change (based on Boström et al. (Citation2017); Pickering (Citation2018)), by challenging dominant discourses and changing institutional rules (Van Tatenhove, Citation2022). Reflexivity consists of three elements: the trigger (the first element) that leads to a process of learning and reflection (the second element), and the capacity to enact change (the third element). As outlined in the introduction, we argue that the trigger for reflexive marine governance is an unintended outcome, a disrupting event or a social movement or environmental pressure point which forces a conscious re-examination of the existing governing system. The emergence of the Anthropocene, and the myriad of planetary crises currently impacting ocean environments and communities that rely on them is an example of a significant trigger that has driven the current focus on reflexive marine governance. The next section will explore the second and cognitive element of reflexivity through the perspective of social learning.

3. Reflexivity and social learning

Social learning extends individual cognitive processes by acknowledging that these take place in a broader social or institutional system. According to Reed et al. (Citation2010) social learning is defined as a change in understanding that goes beyond the individual to become situated within wider social units or communities of practice through social interactions between actors within social networks. Social learning refers not just to individual learning being influenced by a social context and norms, but also that learning takes place in social interaction where people learn from each other in ways that can benefit wider social-ecological systems. A consequence is that learning does not only take place at individual level, but can also take place at group or organizational and societal levels (Reed et al., Citation2010).

A distinction that is often used to clarify how learning at different levels relates to this social context is that of single, double and triple loop learning (McLoughlin & Thoms, Citation2015; Tosey et al., Citation2012). Thinking about social learning in terms of loops stems from Argyris and Schön (Citation1997), who define single loop learning as detecting or correcting an error without questioning or altering the underlying values of the system (Tosey et al. Citation2012). Single loop learning is learning about the results and consequences of existing behavior and daily practices (McLoughlin & Thoms, Citation2015). By observing the consequences of action and by using that knowledge to adjust subsequent action to avoid similar mistakes in the future, successful patterns of behavior and daily practices are developed (Hatch, Citation1997). It is thus instrumental in nature focused on performing actions in the right way to achieve a desired outcome (Reed et al., Citation2010) and rests on an ability to detect and correct error in relation to a given set of operating norms (Johannessen et al., Citation2019; Morgan, Citation1997).

Single loop learning, however, ignores why problems arise and why daily practices need to be corrected in the first place (Hatch, Citation1997). Double loop learning refers to questioning patterns of actions and behavior and knowledge, assumptions and norms that inform these patterns (McLoughlin & Thoms, Citation2015). It is often a response to being faced with a new situation that requires a reconsideration of current frames (Johannessen et al., Citation2019) within the systems that determine what appropriate behavior is. It relies on being able to take a ‘double look’ at the situation by questioning the relevance of operating norms and policies by asking whether these norms or policies lead to the right actions or practices to achieve a desired outcome (Morgan, Citation1997). As such, double loop learning is about discursive learning and change, through which existing frames and norms become questioned.

Finally, triple loop learning is a more recent addition to this framework of learning loops and its conceptualization is subject to debate (Tosey et al., Citation2012). While triple loop learning is seen as a deeper or higher level of learning, there is a lack of consensus what it exactly entails. Some scholars define triple loop learning as reflecting on and discovering why we learn the way we learn (Johannessen et al., Citation2019). Triple loop learning then focuses on the ability to improve the organizations’ capacity for single and double loop learning, by ‘learning about learning’ or ‘learning to learn’ (Keijser et al., Citation2020). Keijser et al. (Citation2020) point at a learning paradox in for example Maritine Spatial Planning. This learning paradox refers to the recognition of the importance of learning, but a lack of a critical appraisal of questions of who, what, why, and how. Posing these questions will point to Marine Spatial Planning and learning processes being contextual in nature, i.e. existing in relation to space and place and the cultures with which they are associated. This points to a second way of defining third loop learning, which is about how we decide what actions or behavior, and thus what policies, norms and frames, are right given the context in which these are situated, i.e. the wider systems of knowledge, values and paradigms that drive the articulation of norms and frames (the object of double loop learning) and of certain actions (the object of single loop learning). Third loop learning is therefore about recognizing root causes of undesired outcomes and the need for a change in epistemology (Gupta, Citation2016; Tosey et al., Citation2012). Achieving the desired outcome means changing existing values and paradigms as well as the knowledge base that shape decision making. At the same time, the fact that triple loop learning is challenging, risky and does not necessarily lead to better outcomes should be considered as well (Tosey et al., Citation2012). In this article, we follow this second conceptualization and define third loop learning as recognizing the structural conditions, including paradigms and social structures, that shape the (re)formulation of social norms and behavior.

Exploring the three loops of learning helps to better define what reflection processes can focus on, such as what is learned, and whether the learning is about (own) behavior/daily practices (single loop learning), frames and norms (double loop learning), or broader powerful social and governing structures and paradigms (triple loop learning). Reflexivity is related to these intersecting learning loops, however, while a cognitive process might lead to a change in understanding of how a marine sustainability issue relates to daily practices, dominant discourses, rules of the game or power relations, it does not necessarily lead to change (Pickering, Citation2018). The next section will therefore further explore how this cognitive element of reflexivity relates to transformative change through the (bounded) capacity of actors to reorient and redirect practices and governance systems. It is also here that we return to the distinction of social learning by individuals, organizations or society. We will also discuss the distinction between reflexivity as an actor capacity and the structural conditions in which reflexivity takes place.

4. Reflexivity and transformative governance change; a multilevel perspective

The third and last element of reflexivity, which is when reflection through social learning translates into reorientation and redirection, brings in the notion of transformative governance change. Learning can focus on reflecting on daily practices, frames and discourses, and broader (governance) context/structures. This section will explore how, due to the duality between structure and agency, reflexivity involves a multi-level dynamic between learning at the actor level (i.e. individual, group, and/or organizational level) and governance learning and change at levels that go beyond the actor level (e.g. at societal level).

We take inspiration from a theory of institutional change in environmental governance, called the policy arrangement approach (Arts & Goverde, Citation2006; Van Tatenhove & Leroy, Citation2000) to explore this multi-level dynamic between reflexivity and transformative governance change. We first discuss how reflexivity at actor level leads to change in policy practices. Second, following the policy arrangement approach, we identify two analytical levels at which transformative governance change can take place. First, at the level of governance arrangements in which actors form coalitions and in interactions use certain discourses, resources and rules of the game to govern a certain policy domain. Second, at the structural level of the political (or societal) system at large (Van Tatenhove, Citation2017; Van Tatenhove, Citation2022; Voß & Bornemann, Citation2011).

4.1. Reflexivity and change at actor level

Single, double, and triple loop learning and reflection by an actor (which can be both an individual, a group or organization) is a process of self-critical introspection and analytical scrutiny of the self, i.e. an actor’s own practices and frames (single and double loop), as well as to how the actor is embedded in a governance arrangement or the broader (political) context, consisting of structures and paradigms that dominate in society (triple loop). Actors are the key agents of reflexivity as these have the agency and capability to reorient and redirect their own ensembles of saying, doings and things (practices). However, such actors are also ‘structured agents’, that is they are embedded in rather stable social institutions making conduct rule directed (Arts & Goverde, Citation2006; Trang et al., Citation2023). Actors and their practices and capacity for reflexivity are guided by a social structure in terms of existing rules of the game, discourses and resources (Van Tatenhove, Citation2022). Reflexivity is thus shaped by the interplay between structure and (reflexive) agency. While agency refers to the capacity of agents (an individual or a group) to affect their own practices as well as the physical, economic and socio-cultural environments within which these practices are situated, structure refers to the organizational and systemic conditions that make up these environments (Toonen & Van Tatenhove, Citation2020).

As a consequence, change does not emerge automatically or easily. Social and institutional structures shape when and how an actor is able to translate its learning into actual de-routinization and (re)developing of its practices. There is as such, a tension between stability and continuity within practices (interactions between actors), governance arrangements and social or political institutional structures (e.g. in order to make decisions) on the one hand and reflexivity on the other (Boström et al., Citation2017). Reflexivity leads to questioning and opening up these practices – and governance structures – for change, but the ability to break out of structures to (re)develop (new) practices is what defines and challenges reflexivity.

Social and political structures can shape reflexivity by constraining or enabling reflection and change. Vested interests play a role in determining whose and what knowledge (as an outcome of learning) counts, and consequently, whether new insights find fertile ground (or not). Societal transformation, learning and reflection – and particularly acting upon it – can be challenged by varying ideas of whether and how transformative governance change is needed, for whom and at what pace. It should thus not be assumed that reflexivity always leads to (transformative) change nor that change is always sustainable. This is illustrated by the variety of ways in which different actors have responded to supposedly transformational governance approaches, such as the Blue Economy, whereby the transformational capacity of the concept to enhance sustainable use of our oceans and resources is widely contested (Cisneros-Montemayor et al., Citation2022; Fusco, Knott, et al., Citation2022; Fusco, Schutter, et al., Citation2022; Hassanali, Citation2020; Schutter et al., Citation2021; Voyer et al., Citation2018). Yet, while social structures guide actors, actors are also able to, through reorientation and redirection, and whilst navigating power and institutional structures, change these governance structures. For example, despite its contested and ambiguous nature, local actors have been able to mobilise the Blue Economy concept to drive governance changes with varying degrees of success and using various interpretations of the concept (Benzaken et al., Citation2022; Hassanali, Citation2020; Schutter & Hicks, Citation2019). How they do so and when this leads to transformative governance change is something we will discuss in the next section.

4.2. Reflexivity and transformative governance change

The actor capacity of single, double and triple loop learning and reflexivity is the starting point of our exploration of how transformative change in governance systems comes about. Structure does not only enable or constrain actors and their reflexivity; it is through this reflexivity and the change in interactions, that agents are able to change the governance structure they are embedded in. Reflexivity is the outcome of the interplay between structure and agency, also because by being reflexive, actors are able to, through interaction, set in motion societal learning and change within a governance arrangement, or even the broader patterns at the level of the political and social system. In fact, in order for change to be transformational, it should transcend the actor’s own changing (organizational) practices.

Reflexivity is only transformational when it leads to a system-wide reorganization across technological, economic and social factors, and paradigms, goals and values (Visseren-Hamakers et al., Citation2021). Transformation is about a significant reordering, one that challenges existing structures to produce something fundamentally novel (Blythe et al., Citation2018). In that sense, transformation is often assumed to be ‘radical’ in nature, referring to addressing the underlying root drivers of a problem rather than its proximate causes and symptomatic effects (Evans et al., Citation2023; Morrison et al., Citation2022; Visseren-Hamakers et al., Citation2021). Transformational change does not necessarily happen quickly and suddenly, as we will discuss below, it can also be a process that unfolds over time. Transformation is also an open-ended process, meaning that it can also lead to unsustainable outcomes, something that Blythe et al. (Citation2018) call the dark side of transformation. Moreover, transformation can only take place through concerted effort at all levels of governance and at multiple locations (Visseren-Hamakers et al., Citation2021). Understanding how different interventions can work synergistically to address the root causes of sustainability issues is one of the analytical challenges that social sustainability scientists face (Morrison et al., Citation2022).

Reflexivity, activated during interaction, is an expression of agency, which mediates the structures within which agents operate (Donati, Citation2010). To understand the relation between transformative governance change and reflexivity, we argue one has to understand reflexivity and change at the level of interactions within governance arrangements (agency) and at the level of governance arrangements in relation to the wider socio-political system (structure) (see ). A governance arrangement is defined as the temporary stabilization of the content and organization of a policy domain (Arts et al., Citation2006). Examples of a governance arrangement are the International Maritime Organization dealing with the prevention of pollution from shipping (Van Leeuwen, Citation2010) or the emerging Deep Seabed Mining Governance Arrangement in the Clarion Clipperton Fracture Zone (Van Tatenhove, Citation2022). The organization of a governance arrangement, i.e. its rules of the game, resources and actor coalitions as well as its content (the discourses) allow governance arrangements to be temporarily stable. Rules of the game are the formal rules and procedures in the different stages of the policy-making process as well as the informal rules that shape and routinise interactions within marine governance.

Following the distinction between single, double and third loop learning, we differentiate between reflectiveness and reflexivity (Van Tatenhove, Citation2017) with reflectiveness referring to a partial change within a governance arrangement. Reflectiveness can take two forms. First, structural reflectiveness refers to the ability of actors to use rules and resources of different institutional settings within an existing discourse, but without changing the rules of the game itself. Second, performative reflectiveness refers to the ability of actors to challenge the dominant discourse, but within existing rules of the game (Van Tatenhove, Citation2017). Reflexivity, however, challenges both discourses, rules of the game and power relations (and thus actors involved), leading to a change of both the organization and content of a governance arrangement. Thus where reflectiveness refers to partial transformation of governance arrangements, reflexivity affects both the content and organization of a policy arrangement. Governance arrangements are then seen as reflexive if actors in an interaction are capable and able to confront, question, learn and amend existing rules, and have the capability to change the rules of the game and mobilise (new) resources to change power relations.

This ability to challenge and change practices is mediated by existing configurations of power, as powerful actors can prevent the unlocking of new practices, values and paradigms (Johannessen et al., Citation2019). Arts and Van Tatenhove (Citation2006) define power as

the organisational and discursive capacity of agencies, either in competition with one another or jointly, to achieve outcomes in social practices, a capacity which is however co-determined by the structural power of those social institutions in which these agencies are embedded.

Transformational change, however, can also take place at the broader level of society itself, i.e. in its political, economic and social domains. Reflexive governance scholars indeed point to the need for changing the foundations of governance itself (Feindt & Weiland, Citation2018; J. Voß & Kemp, Citation2005). Political modernization refers to such structural transformation processes within the political domain of society and emerges from a great variety of social interaction, learning and change in several governance arrangements (Arts & Van Tatenhove, Citation2006). Political modernization is the result of multiple reflexive actors that have been able to change their practices as well as the governance arrangements in which they are embedded. It is as such, an indirect and emergent process of structural governance change (at the level of society at large) and an outcome of the interaction between processes of social learning and change in multiple governance arrangements (Arts & Van Tatenhove, Citation2006). An example is the increased regionalization of marine governance in the European Union (Van Hoof et al., Citation2012), which also affected the governance of pollution from shipping, because next to the International Maritime Organization, also a European governance arrangement for shipping emerged (Van Leeuwen, Citation2010, Citation2015). Such structural change can thus even affect other governance arrangements leading to transformations in discourses, rules of the game, resources and the interaction between actors (Van Tatenhove, Citation2022). Political modernization is thus not only the outcome of processes of reflexivity, but in turn also (re)structures the reflexivity of actors within governance arrangements by defining the enabling and constraining conditions for reflection, and actors capacity to enact social learning and change (see ).

5. Conclusions

Understanding and studying reflexivity and transformational change is urgent as multiple blue crises are already challenging the livelihoods of many ecosystems, communities and industries across the globe. The UN Ocean Decade, the 2023 High Seas Treaty to reverse ocean biodiversity loss, and the Global Plastic Treaty illustrate that global recognition for the need to develop new governance efforts and approaches to protect and enhance ocean sustainability exist. However, as this article and Special Issue argues, such efforts will only lead to transformative change if the very governance foundation on which these efforts are negotiated and adopted transforms too.

This article presented a theoretical exploration of how reflexivity as a cognitive and change process at the actor level relates to transformational change at different levels of actor practices, governance arrangements and wider socio-political structures of society. While putting actors front and center as reflexive agents, the theory proposes that reflexivity is more than a cognitive process of reflection and learning, but also requires a trigger to engage in reflection and learning, and the capacity to change as a result of reflection and learning. The latter is a crucial element for transformative change. It is then through the interaction between structure and agency, that reflexivity can become transformational in nature, i.e. leading to structural change within a governance arrangement and the wider governance system. While reflexivity is an internal source of change enacted by actors within a governance arrangement, it requires spilling over to other governance arrangements to result in wider socio-political system change.

Both reflexivity and transformational governance change are, however, not a given. This article discussed how reflexivity is latent and change only occurs when actors use their capability to translate learning into a change in governance practices and arrangemetns. Reflexivity and change, as the outcome of the interplay between structure and agency, is further restricted because structural elements in terms of resources, discourses and rules of the game do not always enable reflexivity or change. Processes of reflexivity and transformation are inherently political as they involve actors, knowledge, interaction, institutions and power dynamics that shape the process of translating learning into new governance practices, and in structural change in governance arrangements and society. Reflexivity and transformation are therefore not a given and not an easy outcome to achieve; they will require deliberation, contestation and the capacity to break through vested interest, discourses and power structures.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all contributing authors to this Special Issue and others present during either the two online special issue workshops (held June 2022 and April 2023) and/or the June 2023 MARE People and the Sea Amsterdam Conference panels on Reflexive Marine Governance for their constructive discussion and feedback on earlier versions of this article. We would also like to thank the three anonymous reviewers for the valuable comments to further sharpen the theoretical framework developed in this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Judith van Leeuwen

Judith van Leeuwen is Associated Professor at the Environmental Policy Group at Wageningen University. Her research focuses on how public and private actors co-shape the way in which policy concepts and policy instruments are shaped and foster industrial sustainability transitions to reduce marine pollution.

Jan van Tatenhove

Jan van Tatenhove is Professor of Marine and Delta Governance at Wageningen University & Research and the Delta Climate Center both in the Netherlands. His research focuses on processes of institutionalization of marine and delta governance arrangements, reflexive governance, power, and processes of regionalization at regional seas.

Marleen Schutter

Marleen Schutter is a Postdoctoral Fellow at WorldFish in Penang, Malaysia and Ocean Nexus at the University of Washington. Her research interests include the discourse and political economy of defining and enacting sustainability transformations, such as the emergent blue economy.

Michelle Voyer

Michelle Voyer is an Associate Professor with the Australian National Centre for Ocean Resources and Security (ANCORS). Michelle's research focuses on the governance challenges associated with the ‘Blue Economy’, with a particular focus on exploring opportunities for community and Indigenous input, engagement and codesign in emerging and established maritime industries.

References

- Archer, M. S. (2007). Making our way through the world: Human reflexivity and social mobility. Cambridge University Press.

- Archer, M. S. (2010). Conversations about reflexivity. Routledge.

- Argyris, C., & Schön, D. A. (1997). Organizational learning: A theory of action perspective. Reis, 77/78, 345–348. https://doi.org/10.2307/40183951

- Arts, B., Behagel, J., Turnhout, E., de Koning, J., & van Bommel, S. (2014). A practice based approach to forest governance. Forest Policy and Economics, 49, 4–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2014.04.001

- Arts, B., & Goverde, H. (2006). The governance capacity of (new) policy arrangements: A reflexive approach. In B. Arts & P. Leroy (Eds.), Institutional dynamics in environmental governance (pp. 69–92). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/1-4020-5079-8_4

- Arts, B., Leroy, P., & Van Tatenhove, J. P. M. (2006). Political modernisation and policy arrangements: A framework for understanding environmental policy change. Public Organization Review, 6(2), 93–106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-006-0001-4

- Arts, B., & Van Tatenhove, J. (2006). Political modernisation. In B. Arts & P. Leroy (Eds.), Institutional dynamics in environmental governance (pp. 21–43). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/1-4020-5079-8_2

- Beck, U. (1994). The reinvention of politics: Towards a theory of reflexive modernization. In U. Beck, A. Giddens, & S. Lash (Eds.), Reflexive modernization: Politics, tradition, and aesthetics in the modern social order (pp. 1–55). Stanford University Press.

- Beck, U. (2006). Reflexive governance: Politics in the global risk society. In J.-P. Voß, D. Bauknecht, & R. Kemp (Eds.), Reflexive governance for sustainable development (pp. 31–56). Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

- Beck, U., Giddens, A., & Lash, S. (1994). Reflexive modernization: Politics, tradition and aesthetics in the modern social order. Stanford University Press.

- Benzaken, D., Voyer, M., Pouponneau, A., & Hanick, Q. (2022). Good governance for sustainable blue economy in small islands: Lessons learned from the Seychelles experience. Frontiers in Political Science, 4, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2022.1040318

- Blythe, J., Silver, J., Evans, L., Armitage, D., Bennett, N. J., Moore, M. L., Morrison, T. H., & Brown, K. (2018). The dark side of transformation: Latent risks in contemporary sustainability discourse. Antipode, 50(5), 1206–1223. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12405

- Boström, M., Lidskog, R., & Uggla, Y. (2017). A reflexive look at reflexivity in environmental sociology. Environmental Sociology, 3(1), 6–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/23251042.2016.1237336

- Carter, P. (2018). Decolonising governance: Archipelagic thinking. Routledge UK.

- Cisneros-Montemayor, A. M., Croft, F., Issifu, I., Swartz, W., & Voyer, M. (2022). A primer on the “blue economy:” Promise, pitfalls, and pathways. One Earth, 5(9), 982–986. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2022.08.011

- Cisneros-Montemayor, A. M., Moreno-Báez, M., Voyer, M., Allison, E. H., Cheung, W. W. L., Hessing-Lewis, M., Oyinlola, M. A., Singh, G. G., Swartz, W., & Ota, Y. (2019). Social equity and benefits as the nexus of a transformative Blue Economy: A sectoral review of implications. Marine Policy, 109, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2019.103702

- Donati, P. (2010). Reflexivity after modernity. From the viewpoint of relational sociology. In M. S. Archer (Ed.), Conversations about reflexivity (pp. 144–164). Routledge.

- Donati, P. (2011). Modernization and relational reflexivity. International Review of Sociology, 21(1), 21–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/03906701.2011.544178

- Ekberg, M. (2007). The parameters of the risk society. Current Sociology, 55(3), 343–366. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392107076080

- Evans, T., Fletcher, S., Failler, P., & Potts, J. (2023). Untangling theories of transformation: Reflections for ocean governance. Marine Policy, 155, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2023.105710

- Feindt, P. H., & Weiland, S. (2018). Reflexive governance: Exploring the concept and assessing its critical potential for sustainable development. Introduction to the special issue. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 20(6), 661–674. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2018.1532562

- Flannery, W., Ellis, G., Nursey-Bray, M., Van Tatenhove, J. P. M., Kelly, C., Coffen-Smout, S., Fairgrieve, R., Knol, M., Jentoft, S., Bacon, D., & O'Hagan, M.A. (2016). Exploring the winners and losers of marine environmental governance/Marine spatial planning: Cui bono?/'More than fishy business': epistemology, integration and conflict in marine spatial planning/Marine spatial planning: power and scaping/Surely not all planning is evil?/Marine spatial planning: a Canadian perspective/Maritime spatial planning – 'ad utilitatem omnium'/Marine spatial planning: 'it is better to be on the train than being hit by it'/Reflections from the perspective of recreational anglers and boats for hire/Maritime spatial planning and marine renewable. Planning Theory & Practice, 17(1), 121–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2015.1131482

- Fusco, L. M., Knott, C., Cisneros-Montemayor, A. M., Singh, G. G., & Spalding, A. K. (2022). Blueing business as usual in the ocean: Blue economies, oil, and climate justice. Political Geography, 98, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2022.102670.

- Fusco, L. M., Schutter, M. S., & Cisneros-Montemayor, A. M. (2022). Oil, transitions, and the Blue Economy in Canada. Sustainability, 14(13), 8132. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14138132

- Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society: Outline of a theory of structuration. University of California Press.

- Gupta, J. (2016). Climate change governance: History, future, and triple-loop learning? WIREs Climate Change, 7(2), 192–210. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.388

- Hassanali, K. (2020). CARICOM and the blue economy – Multiple understandings and their implications for global engagement. Marine Policy, 120, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104137

- Hatch, M. J. (1997). Organization theory. Modern, symbolic, and postmodern perspectives. Oxford University Press.

- Hendriks, C. M., & Grin, J. (2007). Contextualizing reflexive governance: The politics of Dutch transitions to sustainability. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 9(3–4), 333–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/15239080701622790

- Hickel, J., & Kallis, G. (2020). Is green growth possible? New Political Economy, 25(4), 469–486. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2019.1598964

- Jay, S. (2022). Experiencing the sea: Marine planners’ tentative engagement with their planning milieu. Planning Practice & Research, 37(2), 136–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2021.2001149

- Johannessen, Å, Gerger Swartling, Å, Wamsler, C., Andersson, K., Arran, J. T., Hernández Vivas, D. I., & Stenström, T. A. (2019). Transforming urban water governance through social (triple-loop) learning. Environmental Policy and Governance, 29(2), 144–154. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.1843

- Jouffray, J.-B., Blasiak, R., Norström, A. V., Österblom, H., & Nyström, M. (2020). The blue acceleration: The trajectory of human expansion into the ocean. One Earth, 2(1), 43–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2019.12.016

- Kamil, N., Bush, S. R., & Gupta, A. (2021). Does climate transparency enhance the reflexive capacity of state actors to improve mitigation performance? The case of Indonesia. Earth System Governance, 9, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esg.2021.100111

- Keijser, X., Toonen, H. M., & Van Tatenhove, J. P. M. (2020). A ‘learning paradox’ in maritime spatial planning. Maritime Studies, 19(3), 333–346. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40152-020-00169-z/Published

- Kelly, C., Ellis, G., & Flannery, W. (2019). Unravelling persistent problems to transformative marine governance. Frontiers in Marine Science, 6(APR), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2019.00213

- Mallin, F., & Barbesgaard, M. (2020). Awash with contradiction: Capital, ocean space and the logics of the Blue Economy Paradigm. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 113, 121–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.GEOFORUM.2020.04.021

- McLoughlin, C. A., & Thoms, M. C. (2015). Integrative learning for practicing adaptive resource management. Ecology and Society, 20(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-07303-200134

- Morgan, G. (1997). Images of organization. SAGE Publications Inc.

- Morrison, T. H., Adger, W. N., Agrawal, A., Brown, K., Hornsey, M. J., Hughes, T. P., Jain, M., Lemos, M. C., McHugh, L. H., O’Neill, S., & Van Berkel, D. (2022). Radical interventions for climate-impacted systems. Nature Climate Change, 12(12), 1100–1106. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-022-01542-y

- Pickering, J. (2018). Ecological reflexivity: Characterising an elusive virtue for governance in the Anthropocene. Environmental Politics, 28(7), 1145–1166. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2018.1487148

- Plumwood, V. (1991). Nature, self, and gender: Feminism, environmental philosophy, and the critique of rationalism. Hypatia, 6(1), 3–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-2001.1991.tb00206.x

- Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D. C., Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E., & Weyer, N. (2019). The ocean and cryosphere in a changing climate. IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate, 1155.

- Reed, M. S., Evely, A. C., Cundill, G., Fazey, I., Glass, J., Laing, A., Newig, J., Parrish, B., Prell, C., Raymond, C., & Stringer, L. C. (2010). What is social learning? Ecology and Society, 15(4), 1–10. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/volXX/issYY/artZZ/

- Schmelzer, M., Vetter, A., & Vansintjan, A. (2022). The future is degrowth: A guide to a world beyond capitalism. Verso BOoks.

- Schutter, M. S., & Hicks, C. C. (2019). Networking the Blue Economy in Seychelles: Pioneers, resistance, and the power of influence. Journal of Political Ecology, 26(1), 425–447. https://doi.org/10.2458/v26i1.23102

- Schutter, M. S., Hicks, C. C., Phelps, J., & Waterton, C. (2021). The blue economy as a boundary object for hegemony across scales. Marine Policy, 132, 1–8 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104673

- Steinberg, P. E. (2001). The social construction of the ocean. Cambridge University Press.

- Steinberg, P. E. (2018). The ocean as frontier. International Social Science Journal, 68(229-230), 237–240. https://doi.org/10.1111/issj.12152

- Tafon, R., Glavovic, B., Saunders, F., & Gilek, M. (2022). Oceans of conflict: Pathways to an ocean sustainability PACT. Planning Practice & Research, 37(2), 213–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2021.1918880

- Toonen, H. M., & Van Tatenhove, J. P. M. (2020). Uncharted territories in tropical seas? Marine scaping and the interplay of reflexivity and information. Maritime Studies, 19(3), 359–374. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40152-020-00177-z

- Tosey, P., Visser, M., & Saunders, M. N. K. (2012). The origins and conceptualizations of ‘triple-loop’ learning: A critical review. Management Learning, 43(3), 291–307. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350507611426239

- Trang, T. T., Bush, S. R., & Van Leeuwen, J. (2023). Enhancing institutional capacity in a centralized state: The case of industrial water use efficiency in Vietnam. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 27(1), 210–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.13367

- Tuck, E., & Yang, K. W. (2021). Decolonization is not a metaphor. Tabula Rasa, 38(38), 61–111. https://doi.org/10.25058/20112742.n38.04

- Van Hoof, L., Van Leeuwen, J., & Van Tatenhove, J. P. M. (2012). All at sea; regionalisation and integration of marine policy in Europe. Maritime Studies, 11(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/2212-9790-11-9

- Van Leeuwen, J. (2010). Who greens the waves? Changing authority in the environmental governance of shipping and offshore oil and gas production. Wageningen Academic Publishers.

- Van Leeuwen, J. (2015). The regionalization of maritime governance: Towards a polycentric governance system for sustainable shipping in the European Union. Ocean & Coastal Management, 117, 23–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2015.05.013

- Van Leeuwen, J., Raakjaer, J., Van Hoof, L., Van Tatenhove, J. P. M., Long, R., & Ounanian, K. (2014). Implementing the Marine Strategy Framework Directive: A policy perspective on regulatory, institutional and stakeholder impediments to effective implementation. Marine Policy, 50, 325–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.MARPOL.2014.03.004

- Van Tatenhove, J. P. M. (2017). Transboundary marine spatial planning: A reflexive marine governance experiment? Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 19(6), 783–794. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2017.1292120

- Van Tatenhove, J. P. M. (2022). Liquid institutionalization at sea: Reflexivity and power dynamics of Blue Governance Arrangements. Springer International Publishing.

- Van Tatenhove, J. P. M., & Leroy, P. (2000). The institutionalisation of environmental politics. In J. van Tatenhove, , B. Arts, & P. Leroy (Eds.), Political modernisation and the environment: The renewal of environmental policy arrangements (pp. 17–33). Springer.

- Visseren-Hamakers, I. J., Razzaque, J., McElwee, P., Turnhout, E., Kelemen, E., Rusch, G. M., Fernandez-Llamazares, A., Chan, I., Lim, M., & Islar, M. (2021). Transformative governance of biodiversity: Insights for sustainable development. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 53, 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2021.06.002

- Voß, J., & Kemp, R. (2005). Reflexive governance: Learning to cope with fundamental limitations in steering sustainable development. Strategies, 31, 1–39.

- Voß, J.-P., & Bornemann, B. (2011). The politics of reflexive governance: Challenges for designing adaptive management and transition management. Ecology and Society, 16(2), 1–23.

- Voyer, M., Quirk, G., McIlgorm, A., & Azmi, K. (2018). Shades of blue: What do competing interpretations of the Blue Economy mean for oceans governance? Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 20(5), 595–616. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2018.1473153