ABSTRACT

Few studies have used online reviews to gain useful insights into homestay guests’ satisfaction. This study responds to demands from the existing literature on homestay tourism in a rural destination context to identify the factors that contribute to tourists’ satisfaction and dissatisfaction by examining homestay experiences in Vietnam’s Ben Tre province. User-generated content on Booking.com was analyzed using a netnographic approach. The data comprised 656 online posts. The findings suggest that guests achieve satisfaction from host families’ attitudes and language abilities, high-quality facilities in the bedrooms and grounds, authentic cuisine, a peaceful location, the availability of complementary services, and affordable prices. The findings contradict studies suggesting that homestay guests may seek familiarity, and this was largely not evident in terms of tourist food consumption while at the destination. In addition, the findings challenge studies indicating that prices have a strong influence on tourists’ satisfaction with homestay tourism.

Introduction

Initially envisioned as a budget-friendly means of enabling tourists to experience traditional cultures by lodging with indigenous people in their homes, homestays have come to play a significant role in the sustainable rural development policies and plans of many countries around the world. The benefits associated with homestay tourism are thought to include contributing to local economic growth, promoting the development of local infrastructure and services, providing sustainable livelihood options, assisting in poverty reduction, promoting food security, helping to preserve of local cultures and enabling community empowerment (McCall & Mearns, Citation2021; Pasanchay & Schott, Citation2021; Takaendengan et al., Citation2022). From a supply perspective, homestay tourism can be defined as a type of rural tourism in which tourists reside with local families (Liu et al., Citation2021). This allows guests to experience rural lifestyles, immerse themselves in local culture and spend time in rural areas (Karki et al., Citation2019). Facilities such as bathrooms and living spaces are typically shared by the hosts and guests in homestay accommodation. Homestay experiences often include the opportunity for guests to sample local cuisines and to learn about their hosts’ heritage, perhaps even joining in with traditional cultural practices (Rivers, Citation1998). Hosts benefit from a reciprocal exchange of knowledge about the cultural heritage, customs, and ways of life of their guests: an aspect of homestay accommodation that distinguishes it from traditional forms of accommodation such as hotels (Takaendengan et al., Citation2022; Yuan et al., Citation2018).

From a demand perspective, homestays offer guests a distinctive lodging experience, allowing them to immerse themselves in the local community by staying in the homes of local hosts. Homestay tourism also fosters cultural and social interactions between guests and host communities (Quang et al., Citation2023). These interactions provide insights into local lifestyles and indigenous knowledge, enriching the guest experience (Doan et al., Citation2023). Recent trends reveal a burgeoning demand for rural tourism (Xing et al., Citation2022) and the homestay model has emerged as a way of meeting this growth (Kulshreshtha & Kulshrestha, Citation2019).

Studies of the factors that contribute or detract from satisfying homestay experiences remain scarce (J. W. Bi et al., Citation2024; Quang et al., Citation2023). This is surprising given that the quality of the homestay experience directly influences guests’ overall satisfaction (Tang & Zhang, Citation2024). Existing studies have explored various aspects of homestay experiences such as the participation of women (Quang et al., Citation2023), customer loyalty (Xing et al., Citation2022), tourist awareness (Kasuma et al., Citation2016) and transformative learning (Inversini et al., Citation2022). Most of these studies are, however, based on surveys or interviews of local residents, homestay operators (Fong et al., Citation2017) or guests (Jinsu & Park, Citation2019; Lim et al., Citation2023; Quang et al., Citation2023). None has yet explored the potential of online reviews to serve as a rich source of user-generated data (Dai Quang et al., Citation2023), capable of delivering critical insights into guests’ satisfaction, and how this may in turn influence their decisions, behaviors, and future intentions (Gavilan et al., Citation2018)

In recent years, Vietnam has witnessed a significant growth in homestays in rural areas. This has been driven by the increased participation of women, which has offered them greater economic and social standing, as well as the empowerment of the local community more broadly (Quang et al., Citation2023). Ben Tre, which is in the Mekong Delta region of southern Vietnam, has seen the establishment of over 40 homestays, with the capacity to accommodate more than 1,000 guests per night. However, some of the challenges faced by these homestays in the Ben Tre province includes achieving consistent quality of experiences for guests. In addition, the facilities and services provided are frequently not capable of fully meeting the needs of guests. Indeed, many homestays have been developed without expert guidance and many do not conform to recognized quality standards. Some homestays have shifted their focus on catering to guests’ preferences by neglecting their own cultural identity, thus losing some of their authenticity and novelty (Long & Chau, Citation2022). Other homestays have started offering other tourist services such as sightseeing trips, standard accommodation, dining, and recreational activities, often based on set formulae. This has led to significant duplication in design, service style, menu offerings and experiential programs. Such homestays tend to cater to budget-conscious travelers, making only limited attempts to address the needs of high-end tourists. Meanwhile, homestay hosts and their families tend to have a farming background and are thus not typically trained in hospitality service provision, relying instead on general knowledge and instinct (Xay et al., Citation2018).

This study addresses the above-mentioned research gap by explores the factors that contribute to guests’ satisfaction and dissatisfaction with homestay experiences in Ben Tre province, a rural destination in Vietnam. Using a netnographic approach, user-generated content on Booking.com relating to five popular homestays in Ben Tre (Mekong Home, Charming Countryside, Quốc Phương, Nguyệt Quế and Phúc Sinh) was scrutinized for narratives of satisfaction and dissatisfaction with the guests stay. The dataset comprised 656 online narratives posted between June 2022 and June 2023. Content analysis was then applied to identify the principal sources of guests’ satisfaction and dissatisfaction with their stay. The study thus contributes to the literature on homestay visits. It also offers managerial implications for enhancing guest satisfaction with the homestay experience, benefiting not only to homestay service providers in Ben Tre but also extending its applicability to homestay operators in Mekong Delta provinces, which share a similar cultural context. The findings of this study enrich the growing body of homestay studies and provide guidance on factors that can impact upon the prosperity of rural homestay businesses.

Literature Review

Satisfaction and Homestay Tourism

Researchers suggest that increasing tourists’ satisfaction levels is of crucial significance across the tourism industry (Hallak et al., Citation2018). Providing satisfaction requires those who own and operate tourism businesses to anticipate and understand a person’s responses to the experiences they offer (Abbasi et al., Citation2024). Oliver (Citation2014, p. 8) defines satisfaction as the judgment of tourists that the tourism experience has provided “a pleasurable level of consumption-related fulfillment.” Others define positive satisfaction as the post-purchase evaluation of an experience that equals or exceeds pre-purchase expectations (Vega-Vázquez et al., Citation2017). Tourist satisfaction is, therefore, a subjective post-consumption evaluation of the service and experience encountered while traveling for tourism purposes (Su et al., Citation2011). Conversely, when the experience fails to meet or exceed the level of expectation, the tourist will be dissatisfied and left with a feeling of displeasure (Reisinger & Turner, Citation2003). In this way, consumers compare the quality of the experiences they have received with their prior expectations of that quality, and this results in confirmation or disconfirmation of those expectations (Kao et al., Citation2008). The affective responses resulting from confirmation or disconfirmation form the basis of customer satisfaction or dissatisfaction (Bigné et al., Citation2005).

Regarding homestay in particular, a study by D. Z. Chen (Citation2021) found that affinity, defined as hosts’ ability to become close with, attract and establish harmonious relationships with guests contributed positively to overall guest satisfaction. In another study, D. Chen et al. (Citation2024) suggested that when faced with homestays that perform poorly in other respects, guests still tend to leave high overall scores in their online reviews provided that the hosts show affinity with them. This finding is supported by other studies suggesting that homestays often perform poorly on attributes such as service quality, safety, and noise, but that the satisfaction generated by host-guest interaction can compensate for these shortcomings (Guttentag, Citation2015). Moreover, Tussyadiah and Zach (Citation2017) found that amenities, location, welcoming feel, and home comforts (“vibe” and hospitality) are common considerations for homestay guests. Studies have also found that homestay guests value a geographical location that allows convenient access to facilities such as shops, while good room facilities can meet the basic needs of guests while they are staying in an unconventional style of accommodation (M. Mody & Hanks, Citation2020; So et al., Citation2020). The room facilities variable also incorporates warmth of welcome, attractive layout, comfort, pleasure, relaxation (M. A. Mody et al., Citation2017). Furthermore, according to Guttentag (Citation2015), cost savings or affordable price, amenities and authentic experiences can all enhance the attractiveness of homestays. Examples of amenities include bed linen, cable TV, a hair dryer, hot water, and wine glasses (D. Chen et al., Citation2024).

Melubo et al. (Citation2024) study of homestay tourism in Tanzania found that most tourists from the global West valued the opportunity to taste healthy, natural, and reasonably priced local African dishes, while others can be sensitive to issues of food hygiene and quality. Ogucha et al. (Citation2017), meanwhile, focused on the impact of facilities and services on tourist satisfaction at homestays in the Lake Victoria area of Kenya. Their results indicate the significance of service quality in shaping tourists’ perceptions and overall satisfaction. In addition, Kasuma et al. (Citation2016) identified a positive relationship between tourists’ perceptions of service quality, infrastructure, promotion, and homestay business products. Danmei (Citation2019) investigated the core needs of visitors to Xitang homestays in China. Their study emphasized that tourists are particularly concerned about physical facilities, geographical location, and host’s attitude, which significantly impact their experience level of satisfaction. Xing et al. (Citation2022) examined the relationship between service quality and customer loyalty for rural homestays. Their study indicated that customers’ emotional connection with homestays significantly influences their loyalty.

Based on the above discussions, two gaps in the existing literature become apparent and merit further attention. First, the homestay literature remains open to further comprehensive understandings of visitor satisfaction/dissatisfaction, particularly in the Vietnamese context. Second, netnography as a method of data collection is underutilized as a means of exploring such phenomenon. This study proceeds with the intention of making a meaningful contribution in both areas.

Methodology

Study Area

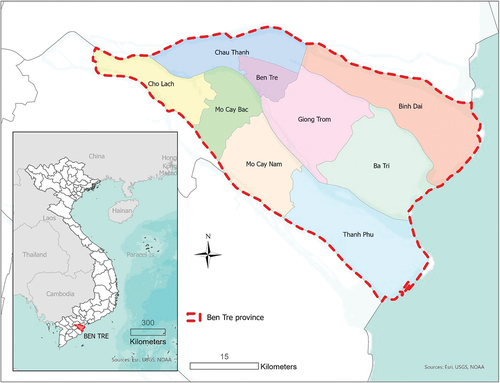

Ben Tre is a two-hour car journey from two major economic hubs in southern Vietnam: Ho Chi Minh City and Can Tho (). This propitious location positions Ben Tre as a favorable setting for the development of rural tourism and homestays in particular. Indeed, the region has a number of advantages that contribute to its potential as a homestay destination. First, Ben Tre has a relatively unspoiled natural landscape that has remained largely untouched by the encroachment of urbanization. The scenery provides an inviting backdrop for tourists seeking an escape from city life. Second, the region is renowned for traditional craft villages, each specializing in the production of distinctive goods. Ben Tre has rich cultural heritage, which is evident in the historical relics and various facets. Third the warm and welcoming disposition of the local population adds to the allure of this destination, providing tourists with an immersive experience in the local way of life. The combination of these factors in Ben Tre creates a compelling opportunity for homestays, allowing travelers to explore the region’s traditions and culture (VCCI, & FSPPM, Citation2020). Ben Tre has attracted an increasing number of international visitors in recent years. In 2019, the province received 1.9 million visitors, taking eighth place among the 13 provinces in the Mekong Delta region. In terms of international visitors specifically, however, Ben Tre was ranked second, receiving around 800,000 arrivals. This activity translated into a total revenue of VND 1,791 billion, positioning the province at sixth place among its Mekong Delta counterparts (VCCI, & FSPPM, Citation2020).

The Netnography Method

This study uses netnography (R. V. Kozinets, Citation2002) for the purposes of data collection. Kozinets (Citation2015, p. 2) defines netnography as “specific sets of research positions and accompanying practices embedded in historical trajectories, webs of theoretical constructs networks of scholarships and citation; it is a particular performance of cultural research followed by specific kinds of representation of understanding.” In tourism studies, netnography has been described as “a novel adaptation of traditional ethnography for the Internet as a virtual fieldwork site” (Mkono, Citation2012, p. 255). Netnography involves the researcher observing or participating in discussions on public online forums, which can provide valuable insight into consumer dialogs (Nelson & Otnes, Citation2005). It investigates narrative and attempts to comprehend social phenomena, while taking steps to maintain objectivity, serving as a faster, simpler, and more cost-effective alternative to traditional ethnography (R. V. Kozinets, Citation2002). R. Kozinets (Citation2010) maintains that when studying an online community, a “pure” netnography can be considered complete within itself and will usually require no off-line ethnographic research.

Netnography was used for three main reasons: first, online travel platforms have become increasingly important information sources for both tourists and researchers (Volo, Citation2010); second, netnography enables researchers to study the behavior of a specific group of people, in this context, rural homestay tourists in Vietnam; and third, narrative analysis of travel blogs can provide textual and pictorial information that allows researchers to understand visitors’ experiences and feelings (Zheng et al., Citation2024). In recent years a growing number of netnographic studies have been published in prominent tourism journals (Thanh & Kirova, Citation2018). Data are typically collected from traveler blogs, online tourist reviews, travel message boards and other virtual tourism Internet media, including chat forums and social networking sites. This is collectively referred to as “user-generated content” (UGC). The UGC is then analyzed thematically using a one or more of a variety of available techniques (Catterall & Maclaran, Citation2001).

The collective sharing of experiences and perspectives by tourists on digital platforms has given rise to a substantial database that businesses and scholars can readily access (Mellinas et al., Citation2016). A good example is Booking.com, which is a prominent platform in this domain. Online reviews have become an important reference for consumers when making purchase decisions, exerting a profound impact on their intentions to book accommodations, particularly when there are many positive reviews (Chan et al., Citation2017). Functioning as a form of electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM), online reviews offer users unparalleled convenience, anonymity, and the ability to overcome temporal and spatial constraints (Tsao et al., Citation2015). Gavilan et al. (Citation2018) emphasize the decisive influence of both overall rating scores and textual reviews on consumers’ online purchasing decisions, as such first-hand reviews are often considered to be trustworthy and reliable. Positive reviews have been found to hold greater influence over consumers’ intentions to book hotels than negative reviews (Chan et al., Citation2017; Tsao et al., Citation2015). It is argued that tourists are generally candid in sharing their personal experiences, including opinions on products, services, facilities, and other facets of hotels and destinations (Barreda & Bilgihan, Citation2013).

Data Collection

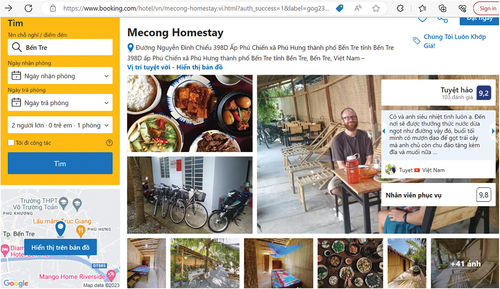

Following R. V. Kozinets (Citation2002), the first step was to identify the online communities most relevant to explore homestay service quality in Vietnam’s Ben Tre province from the tourist perspective. A decision was therefore made to use online reviews posted on Booking.com, a widely used source, for comparative analysis (Gursoy et al., Citation2022). Founded in 1996, in Amsterdam, Booking.com has rapidly grown from a local startup to a global frontrunner in digital travel information services. As per the information available on its website, Booking.com mandates that only guests who have completed a booking through their platform, including those making reservations on behalf of others, can leave reviews for accommodation (). Furthermore, reviews are restricted to submissions made within three months of the guest’s check-out date.

Figure 2. A snapshot of a homestay in Ben Tre province on Booking.com, displaying the overall rating score and tourists’ opinions.

The second step involved data collection. As with all netnography, exhaustiveness is not required: rather, the data-collection process aimed to gather illustrative examples of the phenomena under investigation. Out of the more than 40 homestays in the rural area, the selected sample for this study consisted of the five most popular homestays at the destination (). The selection criteria were twofold: first, the homestays with the highest overall rating scores were selected. This selection was designed to enable the study to comprehend the factors contributing to their high ratings while also identifying any potential areas of guest dissatisfaction; second, the homestays were required to have a sufficient number of reviews within a one-year timeframe, specifically from June 2022 to June 2023. displays the five homestays that were selected to be the subjects of this study.

Textual reviews were then undertaken of the five homestays. The total number of reviews obtained was 656 (). Of these, 87% were submitted by international tourists, with European visitors accounting for 73% of the total (). The reviews were then categorized into two main groups: “liked” and “disliked,” following the predefined classification on Booking.com. As most reviews were written by international tourists, in various languages, the Google Translate tool was used to enable the researchers to understand the content of these reviews. Google Translate is a widely used tool for language translation (Shukla et al., Citation2023). The updated version of Google Translate applies a method of example-based machine translation to improve the quality of translation by learning from millions of examples. It undertakes interlingual machine translation by encoding the semantics of the sentence, rather than simply utilizing phrase-to-phrase translations (Schuster et al., Citation2016).

Table 1. Homestays in Ben Tre selected for analysis.

Table 2. Nationalities of tourists staying at the homestays.

The third step related to the role of the researchers. In netnography, when researchers enter an active online community as participant observers, inquiring and leading communication, they should fully disclose their identities and purposes, obtain informed permission and conduct member checks with key informants (Wu & Pearce, Citation2014). However, when accessing review sites as non-participant observers, it is generally argued that there is no compelling need to communicate research objectives or obtain consent, as these are public (often anonymous) Internet forums, and the posts have often been made months or years in the past (Mkono, Citation2012). This study used a passive, covert approach: i.e., the researchers did not intervene with the naturally occurring or ongoing discussions, nor influence the study subjects. The covert netnographic approach applied here reflects a high personal and social distance between researchers and bloggers (Arsal et al., Citation2010).

Data Analysis

Content analysis was used to systematically explore the content of the UGC posts. This approach has been used to analyze online reviews in tourism research (Barreda & Bilgihan, Citation2013), streamlining text organization and theme identification (Kim & So, Citation2022). A manual coding approach was adopted. After coding, the reviews were categorized, and similar categories were merged (Krippendorff, Citation2022). Individual reviews were categorized within main groups and further condensed by combining similar content, resulting in six major categories that contributed to tourists’ satisfaction and dissatisfaction with the experiences offered by the five homestays ().

Table 3. Main categories and sub-categories with related content.

Findings

Factors Contributing to tourists’ Satisfaction with Homestay Experiences

The results suggest that guests achieve satisfaction from homestay experiences from features ranked in the following order: hosts, facilities, food, location, other services, and price (). In the discussion that follows, the positive attributes linked to specific categories will be presented, followed by the negative attributes.

Table 4. Main categories contributing to satisfaction with the homestay experience.

Hosts

The factor contributing to tourists’ satisfaction with homestay experience in the most posts was hosts. This emphasizes the important role hosts play in shaping tourists’ overall homestay experience. Guests greatly valued the warm hospitality, friendly attitude, and helpfulness shown by hosts and their families, creating a welcoming and comfortable environment during the homestay (66.4% of all posts). Efficient communication in foreign languages, particularly English, stands out as a key factor in guests’ positive impressions. For instance, one guest praised Quoc Phuong Homestay, stating, “He speaks English very well and organized fantastic excursions.” Mekong Home’s host received awards for proficiency in French, with a guest emphasizing its importance. Guests also praised hosts’ willingness to go the extra mile, organizing excursions and helping at inconvenient times of day. They also appreciated hosts’ efforts to find innovative solutions to problems, such as using translation tools to bridge the language gap effectively.

Facilities

Another factor that contributed greatly to tourists’ satisfaction was the facilities offered by the homestay. This was greatly appreciated by guests (48.1% of all posts). Across all the five homestays, the review posts highlighted offering and maintaining good facilities. These include having furniture in the bedroom and essential amenities, as well as external facilities such as a flower garden, a swimming pool or a relaxation area. This is further highlighted by the review post of a Malaysian guest, who mentioned that Charming Countryside’s rooms were equipped with amenities from hair dryers to air conditioning. Another Czech guest praised Phuc Sinh Homestay’s traditional-style bungalow, which featured a garden view and facilities for guests such as hammocks, mosquito nets and a minibar. Mekong Home and Quoc Phuong Homestay differentiated themselves from other homestay providers in the area by offering swimming pools. Indeed, 25.3% of the positive reviews for Quoc Phuong mentioned the swimming pool, while 37.3% of the positive reviews for Mekong Home praised the quality of their swimming pool. Guests used the following keywords to describe their swimming pools: “refreshing for a swim” and “beautiful, nestled amidst lush foliage.”

Cuisine

The third factor driving tourists’ satisfaction with the homestay experience was cuisine. Guests were highly satisfied with the offered cuisine during their stay (47% of posts). Situated in rural areas with limited dining options nearby, homestays become the primary choice for many guests to enjoy meals. This offers visitors a chance to experience local cuisine and distinct culinary characteristics of each family. Guests frequently used words like “delicious food,” “excellent dishes,” “fresh ingredients,” “diverse menu,” and “generous portions” to describe their satisfaction with the dining experiences at the homestays. For example, a British tourist praised Nguyet Que homestay, describing the dinner as the best meal during their entire trip in Vietnam. Likewise, a German guest praised Mekong Home, stating that it served the best meals throughout their journey. Another Italian guest highlighted Mekong Home’s impressive variety of cuisines prepared with fresh ingredients every day. In addition, guests appreciated the opportunity to taste traditional Vietnamese cuisine prepared by the homestay hosts, fostering a deep connection with the local food-and-drink culture.

Location

The findings suggest that the location of the homestay and its surrounding landscape also contributed to the satisfaction with the homestay experience (39.2% of posts). An American tourist praised Nguyet Que homestay for its location and considered it one of their favorite homestay locations, featuring canals, coconut groves and beautiful gardens in the surrounding area. A Swiss guest, meanwhile, commended Quoc Phuong homestay for its peaceful and beautiful location, surrounded by trees and coconut palms. The peaceful location of Phuc Sinh homestay also garnered praise from a Vietnamese guest who appreciated the peacefulness of the location. This is further highlighted by the following keywords in the positive reviews: “quiet,” “serene,” “located right by the Mekong River,” “beautiful scenery” and “abundance of nature.”

Other Services

The findings also emphasize the role of other services, particularly activities, in enhancing guests’ satisfaction with homestay experience (38.6% of posts). Homestays offer a diverse range of organized activities, catering to the diverse interests of their guests. The most popular activities offered include complimentary bicycles, motorcycle rental and sightseeing tours by boat, bicycle, or motorcycle. Guests greatly appreciated and were satisfied with the ease of exploring the surrounding area, particularly when their hosts acted as guides. Positive guest reviews highlighted these experiences and the satisfaction these activities added to their homestay experience. Mekong Home, for instance, offered sunset boat tours, complimentary cooking classes, and free foot massages.

Price

Price also contributed to tourists’ satisfaction with their homestay experience (4.4% of posts). Such posts pertained mainly to room rates, food and drink, and sightseeing services. Among the five homestays, Quoc Phuong received 17 positive reviews linked to price, followed by Phuc Sinh with nine mentions. Guests’ comments highlighted the delicious food offered at a reasonable price in Quoc Phuong and the excellent pricing for the Mekong River trip at Phuc Sinh. The findings indicate that price is not a major concern for some guests as a driver of satisfaction, the focus being on the hosts’ warmth of hospitality, facilities, cuisine, and the location of the homestay. The ability of homestays to offer delightful experiences, culturally enriching activities, and a serene environment seem to outweigh price-related considerations for many guests.

Factors Contributing to tourists’ Dissatisfaction with the Homestay Experience

According to the findings, the factor that received the highest number of negative mentions was the location, with a total of 91 reviews covering issues related to insects, noise, convenience of location and pollution. The second factor related to facilities, with 54 reviews, followed by price, with 16 reviews, other services, with 12 reviews, food with seven reviews, and just one negative review about the host ().

Table 5. Main categories contributing to dissatisfaction with the homestay experience.

Location

In terms of customer dissatisfaction with the homestay experience, location emerged as the most significant factor (14% of posts). The most common complaint among guests was noise, the sources of which were roosters and karaoke activities. Phuc Sinh homestay had the highest number of review posts about rooster noise in the area. This disturbing noise from roosters was reported to be present at all hours, impacting not only the quality of guests’ sleep but also their overall satisfaction with the homestay experience. Noisy karaoke activities were reported as another major concern, affecting both Mekong Home and Quoc Phuong. Guests at these homestays mentioned that Vietnamese people, mainly in rural areas, are fond of karaoke, leading to loud singing in the vicinity.

The convenience of the homestay location also received some criticism (4.3% of posts). Guests highlighted that the homestays’ rural settings make them feel alone and found it challenging to travel because of poor transportation services. Moreover, the rural location of homestays offered guests limited dining options, making them solely dependent on the homestay, which may not always meet their needs.

Insect-related issues, particularly mosquitoes, were also mentioned (3.2% of posts). Guests reported encounters with mosquitoes at Quoc Phuong. Italian guests also shared an upsetting experience of finding mouse feces in their room at Quoc Phuong. Meanwhile, six review posts were related to pollution in the area, i.e., not directly attributed to the homestays. Guests expressed concerns about pollution, such as dirty water and poor waste management, impacting both the homestay environment and the local community.

Facilities

This category emerged as the second factor that contributed to guests’ dissatisfaction with the homestay experience (8.2% of posts). One of the main issues was the discomfort experienced with the beds provided. Numerous negative review posts centered on the quality of mattresses, with guests frequently noting that the beds were excessively firm, making it challenging to have a restful sleep. This aspect significantly impacted upon their overall comfort and led to dissatisfaction. Another common concern reported by guests, particularly at Mekong Home, related to the functionality of the hot-water systems. As the homestay’s hot-water supply relied on solar energy, guests encountered challenges in accessing a constant supply of hot water. The fluctuating hot-water supply interrupted their showering, leading to dissatisfaction among some guests.

In addition, issues related to poor soundproofing in the rooms were mentioned in some of the review posts as a main cause of dissatisfaction. This lack of privacy and soundproofing contributed to a less-than-ideal environment for relaxation. Moreover, a minor concern mentioned by guests at some homestays related to the upkeep and maintenance of certain facilities. For example, some guests noticed instances where certain amenities or rooms were not properly maintained.

Price, Other Services, and Cuisine

Guest dissatisfaction was also linked to other aspects, for example, price. Mekong Home had the most complaints (11 out of 16). Guests, mainly German and Australian, found services like food, drinks, and boat tours costly compared to neighboring areas. Other services were also mentioned. For example, Quoc Phuong received the most complaints (seven out of 12), concerning poorly maintained bicycles and boats. Phuc Sinh faced similar issues with overcrowded Mekong tours. There were seven negative review posts linked to food and guests at Quoc Phuong and Phuc Sinh reported that these did not meet their expectations. Only one review post was linked to the host at Phuc Sinh Homestay due to poor English language skills, which was a cause of dissatisfaction for guests from the Czech Republic.

Discussion

While homestay has been growing rapidly as a form of tourist accommodation in many areas, there have been relatively few studies that attempt to identify the main sources of guest satisfaction and dissatisfaction. Such knowledge is crucial to homestay operators in order for them to remain competitive and, perhaps more importantly, to deliver an authentic homestay experience to their guests. By applying a narrative content analysis UGC data from Booking.com, this study set out to explore the factors that contributed to satisfaction and dissatisfaction with homestay experiences in Vietnam’s Ben Tre province. The study findings suggest that six main factors contributed to tourists’ satisfaction with the homestay experience in Ben Tre province: hosts, facilities, cuisine, location, other services, and price. Meanwhile, five factors contributed to tourists’ dissatisfaction with the homestay experience in Ben Tre province: convenience of the location, facilities, price, other services, and food.

These findings relating to sources of satisfaction were in some ways as expected. First, the findings underscore the pivotal role of hosts in shaping tourists’ satisfaction with the overall homestay experience. Indeed, previous studies have argued that the core of a successful homestay experience relates to the dynamics between the host and the guest (Gunasekaran & Anandkumar, Citation2012). When hosts and their families are warm, friendly, and helpful, guests are more likely to state they have had a satisfactory experience. This is known as “hospitality hosting behavior” – or simply being hospitable to guests – and is widely reported in the literature to be a positive determinant of tourist satisfaction (e.g., Ariffin et al., Citation2013). Related to this is the importance of good communication skills on the part of hosts, which greatly enhance their ability to interact with their guests in a hospitable manner (Scerri & Presbury, Citation2020).

Second, the findings also concur with existing studies emphasizing the importance of accommodation facilities and amenities as one of the most important factors influencing guests’ satisfaction with a homestay experience (G. Bi & Yang, Citation2023; Danmei, Citation2019). However, while there are some similarities within in-room amenities between the homestays and hotels, homestay accommodation is characterized by a lack of standardization due to the varying nature of different properties, and this can be a weakness (Cheng & Jin, Citation2019).

Third, the findings of this study are supported by existing studies indicating that cuisine plays a pivotal role in enhancing guests’ satisfaction with homestay experiences (Ogucha et al., Citation2017; Sengel et al., Citation2015). According to Murphy et al. (Citation2000) and Truong and King (Citation2009), cuisine is one of the factors linked to a sustainable homestay destination that offers additional compelling attractions to potential tourists. In line with existing studies, the review posts show that meals served within homestays left a profound impression among guests. Rural homestays, often nestled in secluded areas devoid of conventional dining establishments, compel visitors to partake in home-cooked meals. This can be considered a form of novelty seeking, where tourists look for new food and consumption experience (Lee & Crompton, Citation1992). Tourist food consumption is a unique form of eating that often occurs in a foreign context (Cohen & Avieli, Citation2004) and the meaning of tourist food consumption goes beyond being a daily, routine practice, to become a significant aspect of the holiday experience (Sthapit, Citation2017). Eating novel foods during a holiday is a mark of an authentic experience that many visitors seek out (Wijaya et al., Citation2013).

Fourth, the study indicates that homestays often appeal to guests due to their location (Tussyadiah & Zach, Citation2017). This finding corresponds to the findings of a study by Danmei (Citation2019) among visitors to Xitang homestay, which indicate the importance of geographic location with guests who are often seeking a quiet homestay. The findings also resonate with Dey et al. (Citation2020) study, which identifies the competitive advantage that can be earned from culturally enriching and naturally captivating homestay locations. Furthermore, the findings emphasize the importance of complementary activities in enhancing tourists’ satisfaction and in offering genuine cultural engagement (Xing et al., Citation2022).

With regard to the factors that contributed to tourists’ dissatisfaction with the homestay experience, many of the findings were again as expected. First, while the peaceful and scenic settings of the homestays contribute to tourist satisfaction, noise from roosters and karaoke parties in the homestay area resulted in guest dissatisfaction. In addition, lack of good facilities, particularly the discomfort experienced with the beds, short supply of hot water and poor soundproofing of rooms, including poor maintenance of certain facilities, resulted in dissatisfaction. The findings are supported by studies highlighting the comfort of beds in the accommodation context (Marshall, Citation2004; Min et al., Citation2002). This can be linked to the concept of sleep-in tourism and that “after sleeping badly, the following day – or a night out, for that matter – is incorrigibly ruined; the service provider (or its competitor) cannot possibly make up for the damage” (Valtonen & Veijola, Citation2011, p. 187). Other dissatisfiers included relative high price, poor quality of other services (particularly linked to poorly maintained bicycles and boats), and poor English-language skills of hosts.

A number of unexpected findings were also noted. First, contrary to some studies indicating that guests to homestays may seek familiarity (Dey et al., Citation2020; Quang et al., Citation2023), this was largely not evident in this study. Indeed, when taken together, the review posts suggest that guests tend to be novelty seekers, particularly when it comes to tourist food consumption while at the destination. This suggests that guests are choosing homestay accommodation not because it is more homely than a traditional hotel but because they can experience the new and different aspects of the home life of their hosts. While the former may be seen as a push factor, the latter is clearly a pull factor. As such, homestay cannot rely on being more homely than hotels: they must also strive to deliver an experience that is novel and interesting for their guests.

Second, contrary to studies indicating that price is an important attribute in influencing accommodation choice (Dey et al., Citation2020) and that a principal reason for booking homestay accommodation is the typically lower price (Sthapit & Jimenez-Barreto, Citation2018), this study found that price was spoken of positively in only 4.4% of the reviews. The finding also challenges some studies suggesting that utilitarian factors, such as price, have a demonstrable influence on tourists’ participation in homestay tourism (Stors & Kagermeier, Citation2015; Tussyadiah & Pesonen, Citation2016). As such, homestay operators cannot rely simply on low prices to satisfy their guests; they must provide value-added facilities and services to generate guest satisfaction.

Third, this study suggests that contrary to studies that emphasize single elements linked to the homestay service experience, such as host-guest interactions or amenities (Pasanchay & Schott, Citation2021; Thapa & Malini, Citation2017), there is a wide range of interacting factors that contribute to homestay guest satisfaction. The findings suggest that homestay guest satisfaction is a multifaceted and complex concept. Many homestay operators do, however, lack specific training in hospitality, while others have only limited language abilities, which may together represent a barrier to the continued growth of the sector and hence its ongoing contribution to sustainable rural development.

Conclusions, Implications, and Limitations

This study contributes to the existing literature by exploring the factors that contribute to tourists’ satisfaction and dissatisfaction with the homestay services in Ben Tre province, a rural tourism destination in Vietnam. In doing so, it challenges several established views presented in the homestay literature, including the view that guests tend to choose homestay accommodation because of its homeliness and lower price. Contrary to expectations, this study found that a major source of satisfaction of homestay guests was the opportunity to experience the home life of others, including their food and family traditions. Price, meanwhile, was neither a major satisfier nor dissatisfier, suggesting that other features of the homestay, such as the hospitality shown to the guests, can outweigh price considerations. An important finding of this study, therefore, is that the factors that influence satisfaction and dissatisfaction with the homestay experience cannot realistically be separated, tending to interact strongly with one another. This may allow one factor to compensate for another, or for more than factor to combine to have a stronger effect. Most previous studies tend to assume that satisfiers and dissatisfiers are independent and can thus be managed individually to raise overall levels of guest satisfaction. The present study suggests that this is not necessarily the case.

Implications

Various implications for homestay operators are offered by this study. First, in view of the importance of the host in shaping tourists’ satisfaction with the homestay experience, hosts should strive to be welcoming and friendly, and to interact actively with the guests, checking in on them and answering any questions they may have. Second it is evident that guests greatly value the facilities, both indoor and outdoor, offered by the homestay during their stay. These include, for example, having air conditioning or a regular supply of hot water for showering, or a swimming pool or outdoor relaxation area. Homestays offering such facilities may have an advantage over others that offer merely a room. Hosts would be well advised, therefore, to provide ample information on what facilities are available, along with photos, on their online homestay profile. Third, many homestay guests are interested in sampling the local cuisine and appreciate the opportunity to enjoy home-cooked meals with their host family. Homestay hosts should therefore aim to provide the option for their guests to eat traditional local food, with authentic ingredients and serving styles. Fourth, homestay operators should be clear on their profiles about the location of the homestay, as well as information about the homestay’s proximity to nearby tourist attractions, restaurants, and transport. Hosts of homestays not located close to such services could consider providing transportation services for their guests. Some already offer the use of bicycles and motorbike hire, but many guests would doubtless welcome the offer of lifts by car or jeep.

While many of the above implications are confirmatory, the study also offers some insights that have not been previously reported. While existing studies have tended to emphasize the tendency for guests to wish to avoid staying in hotels, with their highly standardized, often bland, and impersonal offer, seeking something more similar to their home environment, this study suggests that homestay guests often seek difference. As such, they are seeking not the familiarity of their own home but the novelty of their hosts.’ In this respect, the lack of standardization of homestays may be understood as one of their strengths rather than as a weakness. While lack of standardization is often deemed to be a risk in terms of generating dissatisfaction among guests, it may equally be the case that guests value the unique features of their homestay. It is these that attract the guest to choosing homestay accommodation, rather than dissatisfaction with the standard hotel experience.

The findings also suggest that price is not a strong satisfier or dissatisfier of the homestay experience. Guests are typically concerned with other aspects of their stay and, as long as these are present, do not comment on the price of their stay. This suggests that the factors that stimulate satisfaction and dissatisfaction with the homestay experience tend to be highly interconnected: possibly more so than is the case with other styles of accommodation such as hotels. This is undoubtedly because the guest and host are in much closer quarters to one another, with much greater possibility of both formal and informal interaction with one another. This complicates the task of managing a homestay, implying reinforcing effects as well as tradeoffs. Given that many homestay hosts lack formal training in hospitality, and sometimes have limited language skills, this can be said to represent a significant barrier to the continued growth of the homestay sector. Given its importance in many countries in delivering their rural sustainable development plans, this study emphasizes the importance of providing such training opportunities for homestay providers.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

The limitations in this research must be acknowledged. First, this study is highly destination specific, being restricted to Ben Tre province in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam. Future studies should be conducted in other homestay tourism destinations to attempt to replicate the findings of this study. Second, only five homestays were chosen as the focus for this study. This decision was based on the observation that many homestays have not yet established a robust online presence on prominent platforms like Booking.com. Third, the small sample size of this study calls for future studies to explore a more diverse range of homestay ratings and incorporating broader perspectives, particularly those of domestic travelers. Fourth, this study analyzed the content of comments posted on the Booking.com site. Future research should also utilize other online travel agent websites for a more holistic understanding of their homestay experiences. Fifth, this study assumed a passive, covert lurker position to avoid interfering with the naturally ongoing discussion. Other researchers have suggested, however, that it is important that the researcher becomes a member of the relevant online community when conducting netnography, which is closer to traditional ethnographic standards of participant observation, prolonged engagement, and deep immersion (Zhang & Hitchcock, Citation2017). Future research could therefore adopt an active netnography approach, perhaps by visiting each of the homestays so that they can join in with the discussion on the web platform concerned.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abbasi, A. Z., Rather, R. A., Hooi Ting, D., Nisar, S., Hussain, K., Khwaja, M. G., & Shamim, A. (2024). Exploring tourism-generated social media communication, brand equity, satisfaction, and loyalty: A PLS-SEM-based multi-sequential approach. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 30(1), 93–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/13567667221118651

- Ariffin, A. A. M., Nameghi, E. N., & Zakaria, N. I. (2013). The effect of hospitableness and servicescape on guest satisfaction in the hotel industry. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences / Revue Canadienne des Sciences de l’Administration, 30(2), 127–137. https://doi.org/10.1002/cjas.1246

- Arsal, I., Woosnam, K. M., Baldwin, E. D., & Backman, S. J. (2010). Residents as travel destination information providers: An online community perspective. Journal of Travel Research, 49(4), 400–413. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287509346856

- Barreda, A., & Bilgihan, A. (2013). An analysis of user‐generated content for hotel experiences. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Technology, 4(3), 263–280. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTT-01-2013-0001

- Bigné, J. E., Andreu, L., & Gnoth, J. (2005). The theme park experience: An analysis of pleasure, arousal and satisfaction. Tourism Management, 26(6), 833–844. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2004.05.006

- Bi, J. W., Wang, Y., Han, T. Y., & Zhang, K. (2024). Exploring the effect of “home feeling” on the online rating of homestays: A three-dimensional perspective. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 36(1), 182–217. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-08-2022-1032

- Bi, G., & Yang, Q. (2023). The spatial production of rural settlements as rural homestays in the context of rural revitalization: Evidence from a rural tourism experiment in a Chinese village. Land Use Policy, 128, 106600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2023.106600

- Catterall, M., & Maclaran, P. (2001). Body talk: Questioning the assumptions in cognitive age. Psychology and Marketing, 18(10), 1117–1133. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.1046

- Chan, I. C. C., Lam, L. W., Chow, C. W., Fong, L. H. N., & Law, R. (2017). The effect of online reviews on hotel booking intention: The role of reader-reviewer similarity. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 66, 54–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.06.007

- Chen, D. Z. (2021). Research on the concept, dimensions and the influence of hosts’ affinity on customer satisfaction in homestay: From the perspective of customer perception. Nankai University.

- Cheng, M., & Jin, X. (2019). What do Airbnb users care about? An analysis of online review comments. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 76, 58–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.04.004

- Chen, D., Zhang, W., Bi, J. W., Qiu, H., & Lyu, J. (2024). Hosts’ online affinities and their impacts on the number of online reviews on peer-to-peer platforms. Tourism Management, 100, 104817. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2023.104817

- Cohen, E., & Avieli, N. (2004). Food in tourism: Attraction and impediment. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(4), 755–778. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2004.02.003

- Dai Quang, T., Dang Vo, N. M., Van Nguyen, H., Thi Nguyen, Q. X., Ting, H., & Vo-Thanh, T. (2023). Understanding tourists’ experiences at war heritage sites in Ho chi minh city, Vietnam: A netnographic analysis of TripAdvisor reviews. Leisure Studies, 1(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2023.2249252

- Danmei, Z. (2019). Research on online commentary characteristics of Xitang homestay based on network text analysis. Frontiers in Management Research, 3(4), 157–164. https://doi.org/10.22606/fmr.2019.34003

- Dey, B., Mathew, J., & Chee-Hua, C. (2020). Influence of destination attractiveness factors and travel motivations on rural homestay choice: The moderating role of need for uniqueness. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 14(4), 639–666. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCTHR-08-2019-0138

- Doan, T., Aquino, R., & Qi, H. (2023). Homestay businesses’ strategies for adapting to and recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic: A study in Vietnam. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 23(2), 213–225. https://doi.org/10.1177/14673584221103185

- Fong, S. F., Lo, M. C., Songan, P., & Nair, V. (2017). Self-efficacy and sustainable rural tourism development: Local communities’ perspectives from Kuching, Sarawak. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 22(2), 147–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2016.1208668

- Gavilan, D., Avello, M., & Martinez-Navarro, G. (2018). The influence of online ratings and reviews on hotel booking consideration. Tourism Management, 66, 53–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.10.018

- Gunasekaran, N., & Anandkumar, V. (2012). Factors of influence in choosing alternative accommodation: A study with reference to Pondicherry, a coastal heritage town. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 62, 1127–1132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.09.193

- Gursoy, D., Akova, O., & Atsız, O. (2022). Understanding the heritage experience: A content analysis of online reviews of world heritage sites in Istanbul. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 20(3), 311–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766825.2021.1937193

- Guttentag, D. (2015). Airbnb: Disruptive innovation and the rise of an informal tourism accommodation sector. Current Issues in Tourism, 18(12), 1192–1217. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2013.827159

- Hallak, R., Assaker, G., & El-Haddad, R. (2018). Re-examining the relationships among perceived quality, value, satisfaction, and destination loyalty: A higher-order structural model. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 24(2), 118–135. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766717690572

- Inversini, A., Rega, I., & Gan, S. W. (2022). The transformative learning nature of Malaysian homestay experiences. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Management, 51, 312–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2022.03.008

- Jinsu, K., & Park, Y. J. (2019). A study on the service quality of homestays and pensions in damyang county using mystery shoppers. The Tourism Sciences Society of Korea, 43(2), 101–116. https://doi.org/10.17086/JTS.2019.43.2.101.116

- Kao, Y. F., Huang, L. S., & Wu, C. H. (2008). Effects of theatrical elements on experiential quality and loyalty intentions for theme parks. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 13(2), 163–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941660802048480

- Karki, K., Chhetri, B. B. K., Chaudhary, B., & Khanal, G. (2019). Assessment of socio-economic and environmental outcomes of the homestay program at amaltari village of nawalparasi, Nepal. Journal of Forest and Natural Resource Management, 1(1), 77–87. https://doi.org/10.3126/jfnrm.v1i1.22655

- Kasuma, J., Esmado, M. I., Yacob, Y., Kanyan, A., & Nahar, H. (2016). Tourist perception towards homestay businesses: Sabah experience. Journal of Scientific Research & Development, 3(2), 7–12.

- Kim, H., & So, K. K. F. (2022). Two decades of customer experience research in hospitality and tourism: A bibliometric analysis and thematic content analysis. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 100, 103082. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.103082

- Kozinets, R. (2010). Netnography: Doing ethnographic research online. Sage.

- Kozinets, R. V. (2002). The field behind the screen: Using netnography for marketing research in online communities. Journal of Marketing Research, 39(1), 61–72. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.39.1.61.18935

- Kozinets, R. V. (2015). Netnography: Redefined. Sage.

- Krippendorff, K. (2022). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Sage.

- Kulshreshtha, S., & Kulshrestha, R. (2019). The emerging importance of “homestays” in the Indian hospitality sector. Worldwide Hospitality & Tourism Themes, 11(4), 458–466. https://doi.org/10.1108/WHATT-04-2019-0024

- Lee, T., & Crompton, J. (1992). Measuring novelty seeking in tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 19(4), 732–751. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(92)90064-V

- Lim, T. Y., Leong, C. M., Lim, L. T. K., Lim, B. C. Y., Lim, R. T. H., & Heng, K. S. (2023). Young adult tourists’ intentions to visit rural community-based homestays. Young Consumers, 24(5), 540–557. https://doi.org/10.1108/YC-11-2022-1637

- Liu, F., Wu, X., Xu, J., & Chen, D. (2021). Examining cultural intelligence, heritage responsibility, and entrepreneurship performance of migrant homestay inn entrepreneurs: A case study of Hongcun village in China. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Management, 48, 538–550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2021.08.007

- Long, N. T., & Chau, V. M. (2022). Các Yếu Tố Ảnh Hưởng Đến Quyết Định Tham Gia Du Lịch Homestay Của Du Khách Tại Tỉnh Bến Tre. Journal of Science and Technology – IUH, 58(4). https://doi.org/10.46242/jstiuh.v58i04.4496

- Marshall, A. (2004). Gray matters how to profit from an aging marketplace. Hotel & Motel Management, 219(5), 8.

- McCall, C. E., & Mearns, K. F. (2021). Empowering women through community-based tourism in the Western Cape, South Africa. Tourism Review International, 25(2–3), 157–171. https://doi.org/10.3727/154427221X16098837279967

- Mellinas, J. P., María-Dolores, S. M. M., & García, J. J. B. (2016). Effects of the Booking.com scoring system. Tourism Management, 57, 80–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.05.015

- Melubo, K., Timothy, D. J., Shoo, R. A., & Masuruli, M. B. (2024). The influence of nationality on the activities of international tourists: Perspectives of Tanzanian safari guides. Tourism Planning & Development, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2023.2300146

- Min, H., Min, H., & Chung, K. (2002). Dynamic benchmarking of hotel service quality. Journal of Services Marketing, 16(4), 302–321. https://doi.org/10.1108/08876040210433211

- Mkono, M. (2012). Netnographic tourist research: The internet as a virtual fieldwork site. Tourism Analysis, 17(4), 553–555. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354212X13473157390966

- Mody, M., & Hanks, L. (2020). Consumption authenticity in the accommodations industry: The keys to brand love and brand loyalty for hotels and Airbnb. Journal of Travel Research, 59(1), 173–189. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287519826233

- Mody, M. A., Suess, C., & Lehto, X. (2017). The accommodation experience scape: A comparative assessment of hotels and Airbnb. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(9), 2377–2404. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-09-2016-0501

- Murphy, P., Pritchard, M. P., & Smith, B. (2000). The destination product and its impact on traveller perceptions. Tourism Management, 21(1), 43–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(99)00080-1

- Nelson, M. R., & Otnes, C. C. (2005). Exploring cross-cultural ambivalence: A netnography of intercultural wedding message boards. Journal of Business Research, 58(1), 89–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(02)00477-0

- Ogucha, E. B., Riungu, G. K., Kiama, F. K., & Mukolwe, E. (2017). The influence of homestay facilities on tourist satisfaction in the Lake Victoria Kenya tourism circuit. In Ecotourism in Sub-Saharan Africa (pp. 203–226). Routledge.

- Oliver, R. L. (2014). Satisfaction: A behavioral perspective on the consumer. (2nd ed.) Routledge.

- Pasanchay, K., & Schott, C. (2021). Community-based tourism homestays’ capacity to advance the sustainable development goals: A holistic sustainable livelihood perspective. Tourism Management Perspectives, 37, 100784. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2020.100784

- Quang, T. D., Phan Tran, N. M., Sthapit, E., Thanh Nguyen, N. T., Le, T. M., Doan, T. N., & Thu-Do, T. (2023). Beyond the homestay: Women’s participation in rural tourism development in Mekong Delta, Vietnam. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 14673584231218103. https://doi.org/10.1177/14673584231218103

- Reisinger, Y., & Turner, L. W. (2003). Cross-cultural behavior in tourism: Concepts and analysis. Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Rivers, W. P. (1998). Is being there enough? The effects of homestay placements on language gain during study abroad. Foreign Language Annals, 31(4), 492–500. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.1998.tb00594.x

- Scerri, M., & Presbury, R. (2020). Airbnb superhosts’ talk in commercial homes. Annals of Tourism Research, 80, 102827. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.102827

- Schuster, M., Johnson, M., & Thorat, N. (2016, November 22). Zero-shot translation with Google’s multilingual neural machine translation system. Google research blog. https://research.googleblog.com/2016/11/zero-shot-translation-withgoogles.html

- Sengel, T., Karagoz, A., Cetin, G., Dincer, F. I., Ertugral, S. M., & Balık, M. (2015). Tourists’ approach to local food. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 195, 429–437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.06.485

- Shukla, A., Bansal, C., Badhe, S., Ranjan, M., & Chandra, R. (2023). An evaluation of Google translate for Sanskrit to English translation via sentiment and semantic analysis. arXiv preprint arXiv: 2303.07201. Natural Language Processing Journal, 4, 100025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nlp.2023.100025

- So, K. K. F., Kim, H., & Oh, H. (2020). What makes Airbnb experiences enjoyable? The effects of environmental stimuli on perceived enjoyment and repurchase intention. Journal of Travel Research, 60(5), 1018–1038. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287520921241

- Sthapit, E. (2017). Exploring tourists’ memorable food experiences: A study of visitors to Santa’s official hometown. Anatolia, 28(3), 404–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2017.1328607

- Sthapit, E., & Jimenez-Barreto, J. (2018). Exploring tourists’ memorable hospitality experiences: An Airbnb perspective. Tourism Management Perspectives, 28, 83–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2018.08.006

- Stors, N., & Kagermeier, A. (2015). Motives for using Airbnb in metropolitan tourism: Why do people sleep in the bed of a stranger? Regions Magazine, 299(1), 17–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/13673882.2015.11500081

- Su, H. J., Cheng, K. F., & Huang, H. H. (2011). Empirical study of destination loyalty and its antecedent: The perspective of place attachment. The Service Industries Journal, 31(16), 2721–2739. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2010.511188

- Takaendengan, M. E., Avenzora, R., Darusman, D., & Kusmana, C. (2022). Similiarity check: Socio-cultural factors on the establishment and development of communal homestay in eco-rural tourism. Jurnal Manajemen Hutan Tropika, 28(2.

- Tang, J., & Zhang, X. (2024). A comparative study of emotional solidarity between homestay hosts and tourists. Journal of Travel Research, 63(1), 153–174. https://doi.org/10.1177/00472875221145127

- Thanh, T. V., & Kirova, V. (2018). Wine tourism experience: A netnography study. Journal of Business Research, 83, 30–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.10.008

- Thapa, B., & Malini, H. (2017). Guest reasons for choosing homestay accommodation: An overview of recent researches (sic.). Asia Pacific Journal of Research, 1(4), 2320–5504.

- Truong, T. H., & King, B. (2009). An evaluation of satisfaction levels among Chinese tourists in Vietnam. International Journal of Tourism Research, 11(6), 521–535. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.726

- Tsao, W. C., Hsieh, M. T., Shih, L. W., & Lin, T. M. (2015). Compliance with eWOM: The influence of hotel reviews on booking intention from the perspective of consumer conformity. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 46, 99–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2015.01.008

- Tussyadiah, I. P., & Pesonen, J. (2016). Impacts of peer-to-peer accommodation use on travel patterns. Journal of Travel Research, 55(8), 1022–1040. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287515608505

- Tussyadiah, I. P., & Zach, F. (2017). Identifying salient attributes of peer-to-peer accommodation experience. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 34(5), 636–652.

- Valtonen, A., & Veijola, S. (2011). Sleep in tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(1), 175–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2010.07.016

- VCCI, & FSPPM. (2020). Báo cáo kinh tế thường niên đồng bằng sông Cửu Long 2020. https://fsppm.fulbright.edu.vn/download/VCCI-Fulbright-Mekong-Report-2020_Final_M.pdf

- Vega-Vázquez, M., Castellanos-Verdugo, M., & Oviedo García, M. Á. (2017). Shopping value, tourist satisfaction and positive word of mouth: The mediating role of souvenir shopping satisfaction. Current Issues in Tourism, 20(13), 1413–1430. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2014.996122

- Volo, S. (2010). Bloggers’ reported tourist experiences: Their utility as a tourism data source and their effect on prospective tourists. Journal of Travel Research, 16(4), 297–311. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766710380884

- Wijaya, S., King, B., Nguyen, T.-H., & Morrison, A. (2013). International visitor dining experiences: A conceptual framework. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Management, 20, 34–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2013.07.001

- Wu, M. Y., & Pearce, P. L. (2014). Appraising netnography: Towards insights about new markets in the digital tourist era. Current Issues in Tourism, 17(5), 463–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2013.833179

- Xay, H., Ly, C., & Dang, T. (2018). Du lịch nông nghiệp vùng Đồng bằng Sông Cửu Long: Sản phẩm độc nhưng chưa lạ. Báo Dân Việt.

- Xing, B., Li, S., & Xie, D. (2022). The effect of fine service on customer loyalty in rural homestays: The mediating role of customer emotion. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 964522. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.964522

- Yuan, J., Tsai, T., & Chang, P. (2018). Toward an entrepreneurship typology of bed and breakfasts. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 42(8), 1315–1336. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348017736570

- Zhang, Y., & Hitchcock, M. J. (2017). The Chinese female tourist gaze: A netnography of young women’s blogs on Macao. Current Issues in Tourism, 20(3), 315–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2014.904845

- Zheng, Y., Wei, W., Zhang, L., & Ying, T. (2024). Tourist gaze at Chinese classical gardens: The embodiment of aesthetics (Yijing) in tourism. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 48(2), 353–379. https://doi.org/10.1177/10963480221085958