ABSTRACT

Traditionally a medium for social connectedness between parents and their children, playgroups have been reimagined to include older people. Intergenerational playgroups (IGPs) bring together participants that span across generations, facilitating interactions that promote self-esteem for older people and trans-generational learning for children. In response to challenges to well-being from social isolation experienced by elders, and exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, a virtual IGP was initiated by a playgroup organization, intended to harness technology to facilitate interactions between preschool-aged children, parents, and residents of aged-care facilities. This paper evaluates a virtual IGP program via the review of program development, implementation, and related wellbeing outcomes. The paper provides recommendations through a framework to enhance the planning and execution of future virtual IGPs.

Background

Playgroups are community-based groupings that bring children and their adults together for play and social experiences (Dadich & Spooner, Citation2008). A range of community organizations offer playgroups for purposes of socialization, novel play experiences, and to learn new skills. Participation in culturally and geographically diverse community playgroups has social benefits for participants (McLean et al., Citation2020), including developing friendships and informal social networks with other families through shared experiences of parenthood (Playgroup Australia, Citation2016). As community-based initiatives, playgroups are responsive to the needs of those who attend (Dadich & Spooner, Citation2008). The move by some playgroups to traverse into aged-care facilities is motivated by a desire for connection with older people, motivated also by a desire to reduce social isolation often felt by residents in aged-care facilities. Aged-care residential facilities are designed for older adults who cannot live alone, offering 24-hour accommodation and personal care, along with access to nursing and other health services (Australian government, Citationn.d).

Intergenerational playgroups (IGPs) push the boundaries of social connectedness by bringing different generations together in a play-based context with planned opportunities for gathering, connection and shared learning (O’Sullivan et al., Citation2021). IGPs offer the same benefits as more common playgroup models with the specific addition of promoting trans-generational interactions for social inclusion (Davis et al., Citation2012; Williams et al., Citation2012).

When conducted face-to-face, IGPs promote social connections within local communities (Gualano et al., Citation2018; Hernandez et al., Citation2020), with happiness, dignity, and self-esteem for older people all reported (Skropeta et al., Citation2014). Short‐DeGraff and Diamond (Citation1996) identified the social connectedness as a particular benefit for older people. The deliberate pairing of younger and older people enabled engagement, and reduced prejudice and promoted equal status between groups as they embarked on joint goals (such as activity set-up) (Gerritzen et al., Citation2020; Low et al., Citation2015). However, intergenerational playgroups are complex. Even when supported in face-to-face environments, social connectedness takes time. While careful planning and facilitation of playgroups leads to the active participation of people across generations, this requires skill and time (Hernandez et al., Citation2020).

Initial analyzes of intergenerational program reviews show there has yet to be a systematic review specifically focused on the nuances of IGPs. Existing reviews (published in the last five years) focus either on general intergenerational programs, or specific programs that cater for older people with dementia, for example (Gerritzen et al., Citation2020; Lu et al., Citation2020). Consequently, there is no research that consolidates the characteristics of IGPs, without which, the full potential of IGPs to deliver quality outcomes for participants is unrealized. Evaluations of IGPs are therefore a necessary first step to respond to this gap in the literature.

Wellbeing is a dynamic and multi-pronged construct capturing personal happiness, satisfaction, and mental capital (which encompasses resilience, self-esteem, cognitive capacity, and emotional intelligence). The pathways to wellbeing are varied and complex. “The Five Ways to Wellbeing” framework (Aked, Citation2011) provides a lens to view wellbeing across five key concepts: connecting, being active, taking notice, continuing to learn, and giving.

Connecting refers to how individuals associate and invest with one another, capturing broad and deep relationships with family, friends, local communities and, for the purposes of this study, playgroups. The benefits are well-established in the literature, linked to increased self-esteem, a sense of belonging and self-worth, and lower levels of depression. (Haslam et al., Citation2015)

Being active captures mental and physical activity with benefits extending beyond physical health (e.g., obesity, decrease in cardiovascular disease) to include improved sleep and lower levels of anxiety, stress, and depression.

Taking notice involves being aware of oneself, others, and the environment. Developing an understanding of “others” is important for children’s development of self-understanding and self-regulation. For adults, taking notice involves being present in the moment, being more conscious of surroundings and being more mindful of thoughts and emotions.

Continuing to Learn involves the acquisition of skills and knowledge, goal setting, and engagement in new experiences. Learning new things is important for cognitive growth and development (Park et al., Citation2014), and increases our capacity to problem-solve and cope with stressful situations.

Giving captures an individual’s ability to help others and includes acts such as joining a community playgroup, doing something for someone else, teaching a new skill, or helping someone to achieve a goal. Helping others is associated with increased life satisfaction, feelings of competence, improved health, reduced stress, and an elevated mood.

In the context of wellbeing, IGPs provide the potential for intergenerational connectedness, promoting both an individual and collective learning context in which wellbeing can be nurtured and achieved. Social isolation has detrimental effects on health, wellbeing, and cognitive functioning (Khosravi et al., Citation2016) and was exacerbated for all during the COVID-19 pandemic. Globally, residents of nursing homes were heavily impacted by the pandemic which brought many challenges (Chee, Citation2020; Wu, Citation2020). Reduced levels of social interactions due to infrequent contact with others was a particular concern (Barbosa Neves et al., Citation2019; Cloutier-Fisher et al., Citation2011; Wu, Citation2020).

To respond to the absence of opportunities for face-to-face interactions during the COVID-19 pandemic, innovative uses of technology was looked to as possible solutions to reduce feelings of social isolation and provide opportunity for social connectedness. Khosravi et al. (Citation2016) systematic review of technology-based interventions highlights approaches including social networking sites (SNS, such as X, formerly Twitter, Facebook and chatrooms), robotics (such as a digital pet), video games (such as Wii), tele-care (delivering professional health and support services), and 3D environments (using an avatar).

Previous intervention research shows feasibility in older and vulnerable populations (Ni et al., Citation2018) but it is still unknown how virtual models can successfully house a digital space to establish successful intergenerational programs, especially intergenerational playgroups.

The current study

Confronted by a desire to respond to social isolation amid the challenges of COVID-19, a playgroup organization in Australia initiated a pilot virtual IGP in collaboration with an aged-care residential facility with support from a technology company. This IGP aimed to harness the use of technology as a vehicle through which to facilitate the social connections between preschool aged children, their parents, and residents of older care facilities.

The study draws upon an organization’s long history of providing community playgroups that enable pre-school children and their parents to meet and play in a relaxed environment to generate fun, learning, and friendship. Intergenerational playgroups (IGPs) have become a particular focus and prior to the COVID-19 pandemic they worked in research partnership to explore facilitated IGP models in aged-care and early childhood facilities (Kervin et al., Citation2019-2021). The Australian state where this research occurred experienced two significant COVID-19 lockdown periods; the first March – August 2020, the second June – October 2021. During these periods, requirements for self-isolation, limits on gathering and movement, restrictions on businesses, and controls on entry into NSW were enforced.

Aims

This paper aims to evaluate the virtual IGP by reviewing the program and implementation, to understand wellbeing outcomes for participant groups. The study is shaped by the following research aims:

(1) To capture key stakeholder experiences and perspectives on the perceived benefits of attending the virtual playgroup.

These include parents, Mental Health Professionals at the aged-care facility, and older people residing at care facilities who participated in the playgroups.

(2) To gain insight into the establishment of the IGP and the developed program.

This was achieved through the identification of strengths and weaknesses of the program, considering the perspectives of all participants (i.e., older and younger people, and the different organizations involved) on the design and content of the playgroup.

The “Ways to Wellbeing” framework was used to identify and understand contributory factors for both successful implementation and sustainability of the playgroups.

Methods

Study setting, context and participants

Ten pre-school children and their families, with ten aged-care residents paired with ten Mental Health Professionals (MHPs) participated in the virtual IGP program. The weekly 45-min long playgroups ran for 9 weeks across June and August 2021, when state lockdown restrictions were enforced. In the first two sessions children, their families and MHPs, were divided into two groups to familiarize themselves with digital technology. Children and their families were based across Western Sydney, the Southern Highlands, and the South and North Coast of New South Wales. Older people resided in several aged-care facilities across Sydney, designed for senior Australians who can no longer live in their own homes (Australian Government, Citationn.d.). The researchers were brought in during the process for the purpose of evaluation. Adult participants provided informed consent, and child assent was sought in order to be part of the evaluation. The project had ethical approval from the Human Research Ethics Committee at the University of Wollongong.

Design & procedure

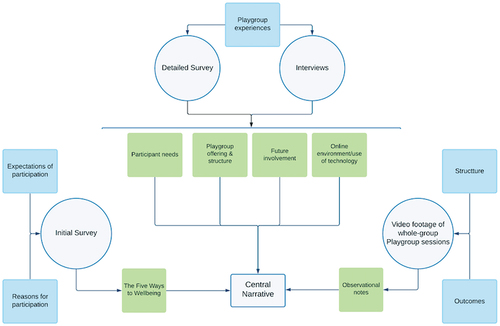

Playgroup philosophy, content and design/structure were developed by early childhood professionals who had previous experience of facilitating face-to-face IGPs. The project used qualitative methods to explore the experiences from the perspective of the stakeholder groups. Details of data collection, in relation to the research aims are in .

Table 1. Table detailing method of data collection in relation to overall and specific research aims, and how many were completed by each stakeholder group.

Data analysis

Initial survey results were analyzed according to “The Five Ways to Wellbeing” (Aked et al, 2008) and the research aims of the evaluation (). Analyses of playgroup experiences focused on i) participant needs (reasons for participation, expectations, perceived benefits of involvement), ii) playgroup structure (quality of activities, flexibility, planning input), iii) future involvement in a similar program, and iv) online environment and technology use (usability, fulfilling perceived expectations). Video footage gathered across the breadth of playgroup recordings (360 min) were viewed by the research team to understand playgroup structure and outcomes as a result of participation and to inform understanding of the explicit aims and objectives of the sessions, predictable routines, and activities. Data were triangulated in connection with research aims, shaping the findings into a central narrative (), used to frame the discussion of results.

Results

The results are organized into two distinct areas.

Part 1: Rationale and aspirations for the virtual IGP.

Part 2: Planning and implementation of the IGP sessions.

Part 1: aspirations for the virtual IGP

In this section we draw upon semi-structured interviews and initial surveys (see ) to capture different interests of virtual IGPs participants. We look to reasons given for participation and expectations of participation in the playgroups in three domains: connecting, taking notice, and giving.

Connecting

A desire for connection was a clear driver for the adult participants. A third of parent responses identified their reason for participation were within the connecting theme. Collectively they expressed they wanted their children to develop relationships with the older generation through meaningful conversations and 1:1 connection with comments: “to develop healthy relationships with older people” and “to bring some joy to the lives of elderly people who may be lonely and in need of friendship.” Older people’s answers to the questionnaire were also predominantly related to connecting, accounting for just over a third of their responses. Older people perceived connection in a similar way to parents and expressed an interest in meeting with and talking to children, meeting new people in general, and engaging in 1:1 time with children and their parents. In their responses, older people identified: “to meet the children,” “I could meet new people and it would get me out of myself” and “I hope to get one-to-one time with a child and parent” as particular motivators expectations of IGPs.

Giving

Featured as reasons for participation, parents felt that their attendance with their children could contribute to reducing the social isolation felt by residents in aged-care facilities and “put a smile on their faces” by being able to “give something back to the elderly” (Parent). Similarly, older people wanted to share their stories and experiences with the children. This sentiment was also echoed by support staff working directly with the older people in the program who mentioned that opportunities to share stories gave older people purpose. The playgroups were seen as “a fantastic way for older people to feel important and have a sense of purpose” and bring about “positive social change” through how “children learn through our elders”. (support staff at aged-care facility).

Taking notice

Parents, in particular, saw IGPs as an opportunity for children to be more conscious of their surroundings and take notice through listening to others and hearing of their experiences. Specifically, parents identified opportunities to appreciate and respect others, hoping their child would develop a sense of compassion and understanding of differences through participation. For older people, they wanted to learn about children’s families, and to see children playing, identifying this would bring them a sense of joy.

Part 2: planning and implementation of the playgroups

In our focus on planning and implementation of the IGPs, we address three contributory factors: use of technology, the IGP program, and building of community.

Use of technology

Each playgroup was held weekly via WebEx, a cloud-based platform on which group video calls can be made, screens can be shared, and breakout rooms enabled. The platform also enables group and 1:1 messaging, and IGP sessions engaged participant communication through verbal and visual interaction (via simple hand-gestures like thumbs up). WebEx affordances also enable enhanced speech perception and noise reduction, automatic transcription of calls and real-time subtitles and translation to promote inclusivity. Participants used a tablet (iPad) to attend playgroups. On these devices various applications (apps) were installed, intended to facilitate engagement. One of these apps was Seesaw, a learning platform that enables people to communicate via sharing photographs, posting comments and liking posts within a private group. All playgroup participants were encouraged to share pictures and make comments between virtual playgroup sessions via Seesaw. Inspired by the theme of the week for the IGP (e.g., dinosaurs, pajama day), data saw parents post pictures of their children’s aligned activities after that playgroup session. There was some parent confusion around the function and purpose of the different platforms and apps (WebEx and Seesaw). In particular, one parent didn’t, “anticipate the need for the time needed for Seesaw, with juggling work etc. it was a time restraint.” This extra time pressure meant that this parent did not engage with SeeSaw, and described “a reliance on Seesaw to develop the relationship rather than the session itself.” (Parent). Another parent reported that they, “did not use a lot of Seesaw, I’m not sure we ever used it” due to technical issues. “At the start there was always a conflict, and I would have to call [the facilitator] and she would call [the other facilitator], they needed a passcode and it got too complicated, too much of a bother – so I gave up.”

Technology experts led training for playgroup facilitators and the families in the first two playgroup sessions of the program. Facilitators were trained in the use of the iPads and functionality of both WebEx and Seesaw. Children and families were taught some online-etiquette “ground rules” which included being off-mic (on mute) except when speaking, waving to notify the facilitator if they wanted to speak, and using “thumbs-up” to agree with or like contributions from other playgroup members.

The enlisting of mental health professionals (MHPs) and subsequent recruitment of older people occurred in the later stages of playgroup organization and, as a result, neither the MHPs nor the older participants received technical training on functions such as “using a touch screen, swipe motions, even turning it on”. Data showed that many of the older people who were recruited experienced some anxiety over the use of the devices, which impacted their sustained participation. An MHP described older people didn’t sign up or withdrew “due to anxiety around technology, lack of experience, or with poor previous experience” (Aged-care facility).For those older people that did consent, many required additional support to be able to fully interact with the chosen technologies with “no existing skills to build on” (Aged-care facility). Further, their lack of previous experience with both technology and playgroup structures, was confounded by recent poor experiences with telehealth consultations and health issues, for example, “for those with hearing impairment and connectivity with the external speaker” (Aged-care facility).

The MHPs also experienced issues with the usability of the technology and were often unable to answer their clients’ questions. Feelings of low confidence in the use of technology (by older residents) accompanied by a lack of effective support resulted in early attrition from the playgroups. MHPs were “under the impression we would be getting a Silver Sneakers [type program], and they would be coming out for two weeks beforehand so we could introduce them [older people] and train them on the technology.” (Silver Sneakers is a community exercise outreach program for older people). MHPs were aware of the initial reluctance of older people to get involved, based on their inexperience of using technology. This lack of familiarity with the technology impacted retentions, and the aged-care residences had “early drop-outs because we didn’t have the [technology] support” (Aged-care facility).

The lack of familiarity and fluidity with technology also impacted the frequency of how often the older people could access the tablets. It was felt by most participants that technology-use support would have contributed positively to the development of a sense of community and connection across the generations. This therefore presents as a clear opportunity for improvement.

There was some discrepancy in the data collected in terms of whether support staff had been trained. There was also some confusion around the access that older people had to the tablets. While it was the expectation of the technology partners that the older people would have access to devices both during and between sessions, this did not appear to have happened. Sustained support from MHPs at the aged-care facility was critical for older people’s engagement in IGPS.

Key findings about the use of technology include 1) the need for clarity around the purpose of each component of the digital resources and their expected use in the IGPs and 2) availability of technology training for all participants.

IGP program

The team of MHPs were enlisted in the latter stages of planning, a short time prior to playgroup commencement. The evaluation team were also commissioned after the IGPs had started. The late involvement of both stakeholders meant there were minimal opportunities to influence the program. Adequate time to familiarize the older participants with the technology was not planned in, aged-care professionals were not consulted on the playgroup design and the potential for playgroup participants to consent to be research participants was hindered.

Analysis of recorded footage from the playgroups, supported by conversations with the facilitators, revealed each playgroup session followed a predictable structure, where each element was led by a playgroup facilitator and lasted an average of 43 minutes (noting that variations time for the individual playgroups was influenced by participation of participants, see ).

Table 2. Table to show the general structure of the playgroups.

The data demonstrate consensus amongst participants that the IGPs were early childhood focused, and not always relevant across generations. While the early childhood facilitators utilized their expertise to design virtual playgroup activities informed by previous experience with face-to-face IGPs, the challenge of pivoting to a virtual platform in a short time frame – reactive to the COVID-19 pandemic – is worthy of attention. Participants reported there was very little opportunity to contribute to or provide input to the design of IGP sessions, feeling the program was attempting to directly transfer the face-to-face playgroups into a virtual context.

Moving face-to-face elements (such as sharing and discussion) to whole group interaction in an online environment made spontaneous interactions difficult. Respondents further reported the activities did not promote cross-generational interaction. For example, singing child-focused songs while muting the speaker meant it was difficult for older people to contribute. This was attributed to the virtual nature (highlighting the lack of adaptation of the activities from an in-person to a virtual context), underutilization of the affordances of the technology, and the collective limitation of the technology and IGP structure to enable fluid conversation (due to group size, the encouraged mute function, lack of spontaneity, breaking conversation or forgetting what was going to be said). One MHP suggested “some consultation for what activities they [facilitators] did would have been good to help that connection…either coming up with a story or theme that connects them [older people] with something about their life.” Collaboration with aged-care professionals with specific knowledge of proven successful aged-care appropriate activities would have benefitted the planning stages.

Playgroup facilitators did engage in ongoing reflection and made modifications across the sessions. Parents reported that the activities improved toward the end of the program with the inclusion of interactive activities (such as Crazy Hair Day and Bingo) which involved all participants. While these activities were reported as being more engaging, they were still governed by defined roles of those involved and rules of participation. This included, but is not confined to, the educator-led nature of the playgroup in which participants were invited to speak by the facilitator. These acted as operational barriers to conversational, fluid, and spontaneous participant contributions.

Despite this change in the latter stages there was a general feeling that the virtual platform prevented a deeper connection between children and older people. The full extent of usability services of the platforms were not utilized, Contributory factors included a lack of small group or 1:1 communication, heavy weighting on facilitator-led activities, and a lack of engagement outside the playgroup designated time. In response to the introduction of smaller groups using the break-out feature, one MHP reported that “everyone loved, it was so much better to have 5 min of no structure and be a bit silly.” However, the challenges with attrition and health of older people did result in changes to who was able to participate, an MHP reports, “The smaller groups used to change every week though – no consistent pairing”.

Key findings about the IGP program include: consultation with all participants to inform program planning, acknowledgment that the virtual environment requires different strategies for interactions than face-to-face (with unique affordances), and IGP experiences need to be cross generational.

Building of community

While there is potential for community building in IGPs, it took some time to realize the potential. One parent expressed that the program was advertised as an IGP, yet she felt there was “very little opportunity to form personal connections with an older person,” an opinion echoed by other parents. Similarly, MHPs did not feel that the playgroup fulfilled the expectations of the older participants as they also weren’t able to make personal connections with children, assuming more of a viewer role. Moments when older people and children could connect through direct conversation were beneficial to all stakeholders. The introduction of break-out rooms in later sessions increased the one-to-one conversations and highlighted the potential for virtual intergenerational connection.

Among aged-care professionals it was felt that the cohort of residents had a significant impact on the success of the IGP. By consequence of collaborating with a specific MHP team, older participants in this study came into the IGP experience with significant illness and high-support needs (including anxiety, depression, and dementia), and this is likely to have affected their ability to adapt, learn and benefit from the virtual program. MHPs visited their older people once per week. Dependency of older people on their assigned MHPs was clear when further lockdown restrictions prevented visitation, resulting in many older people departing from the playgroups. This highlights the inability of the older people to independently engage with the technology required for the virtual playgroups. In retrospect, it was felt that the IGPs may have provided greater benefits to older people who are at-risk of ill health due to their social isolation (which was worsened by pandemic restrictions).

Facilitators reflected that when a cluster of older people from a facility took part in the playgroup they collaborated and were able to come together between the playgroup sessions. In turn, they became less socially isolated with their own co-residents, with the playgroup acting as a springboard on which reflection and shared discussion ensued. The virtual IGP sessions created opportunities to create community within organizations as residents had a shared experience.

In response to the initial survey, one parent strongly agreed that they would continue with the virtual playgroup and would recommend it to other pre-school children (her child did not attend a formal preschool or daycare). In answer to the same question, the remaining two parents answered, “somewhat agree.” All parents said they would recommend the group to older people, an opinion not shared by the MHPs. The MHPs all said they would not want to participate in a similar group in the future.

Key findings about building community include: building virtual community takes time and careful attention to affordances of technology, and virtual connection becomes more powerful when supported with opportunity too for physical connection.

Discussion: recommendations for the IGPs for wellbeing

Overwhelmingly, the desire to participate in opportunities to connect with each other in genuine and meaningful ways was central to all participants. Building upon findings from three contributory factors for the planning and implementation of IGPs, we now return to the “The Five Ways to Wellbeing” framework (Aked etal., Citation2008) and its five key concepts to consider each domain. In doing so, we identify recommendations for future virtual IGPs. provides key considerations for each domain. It is important to note that while we have separated the components of “Ways of Wellbeing” to identify specific affordances of the technology, as interrelated concepts, wellbeing outcomes are best considered simultaneously. As such, recommendations are organized by playgroup design and execution, and discussed in terms of how these may contribute to wellbeing outcomes.

Table 3. Ways to Wellbeing and opportunities for digital interaction.

Facilitating successful collaboration between younger and older individuals necessitates a mediator to establish an environment conducive to small group dialogue and communication, where joint participation in activities is enabled. Activities that integrate music, story, visual arts and movement lend themselves to trans-generational engagement and interaction. This offers all participants opportunities to actively contribute and feel valued (contrary to passive participation). Creating a space that encourages creativity, spontaneity, and playful for all further enhances this sense of connectedness.

Activities need to be more consciously designed for an intergenerational audience for mutually beneficial outcomes for older people and children and to nurture a sense of connection. Activities that integrate music, story, visual arts and movement lend themselves to trans-generational engagement and interaction. Participants from across generations are more likely to experience wellbeing outcomes in smaller social groups and when activities themselves are cross-generational (i.e., neither only child-like nor focused on older people) with inclusive activities for all participants. Examples of such activities could include storytelling about shared experiences (e.g., what you can see out your window). Activities that promote conversation among participants (Gualano et al., Citation2018) about topics of significance (such as family, pets) build community. While there are limitations to achieving fluid conversation between participants on a virtual platform, it is likely that smaller groups and full usability of the technology (such as breakout groups where a child and their parent could be partnered with an older person and their MHP) could help to nurture a sense of connection through dialogue and more intimate conversation exchange.

Collaboration and consultation with key stakeholders (early childhood and aged-care professionals and families) is of utmost importance. Each participant group needs to feel useful to the experience with opportunity to give; consolidated by van Vliet et al. (Citation2017), feelings of usefulness are described as “being helpful to others,” feelings of a “sense of purpose,” and “linked to social well-being.” Cross-generational experiences, characterized by mutual goals, provide opportunities for participants to share experiences and knowledge for the benefit of everyone involved.

Recruitment of participants is critical for IGPs. The virtual context may be more appropriate for older people at risk of developing mental ill-health due to loneliness, rather than those already suffering from dementia, anxiety, and/or depression. Participants need to be receptive to learning new technology skills to reduce the time pressures placed on others to enable their engagement. All participants need to have access to the necessary technology and time to practice and explore to enable autonomy of use, both within and external to the playgroup sessions.

Opportunities for physical connection around the virtual IGPs is important. For children and their parents/carers they were able to talk with each other and revisit experiences. For older people, being part of a participant-group that includes other residents from their facility, would enable in-person connections beyond virtual interactions. Creating a community of practice from the shared experience enables conversations, recollections and reflections beyond the IGP sessions.

In summary virtual IGPs should take into account

An understanding of what “intergenerational” means to all stakeholders and how these understandings can be encapsulated in planning and implementation of playgroup sessions to foster meaningful intergenerational connection that meets the expectations of all participants.

Greater understanding by those who plan and interact with playgroups of the affordances of technology, and how synchronous playgroup sessions can be supported through asynchronous activities.

Support and specific training for all participants (including support people) to use technology and other virtual platforms independently enough to enable genuine social connection.

Co-design of playgroups to ensure professional expertise (from both early childhood and aged-care experts), children and older people are represented, embedded, and consolidated throughout the design and implementation phases to ensure the needs of all participants are met, including how participants are recruited.

Opportunities to nurture a community of older people both during and between playgroup activities, including opportunities offered by aged-care facility recreation programs to enable older people to maintain connection with other residents in the program.

Conclusion

In the context of a virtual playgroup implemented to support community members in light of COVID-19 restrictions, there was overwhelming support for the potential for IGPs to engage children, parents, and older people in playful activities for the benefit of all participants. There was support from all participants for the creative endeavor of IGPs.

“The Five Ways to Wellbeing” framework provides a way to evaluate the program of play activity and experiences within. Overwhelmingly, participants chose to engage with the IGP to connect, take notice, and give. Families saw the playgroups as a social opportunity for their children to connect with older people. For older people, the playgroups provided an opportunity to belong to a group where relationships with younger people may be formed. Given the context of the virtual IGP during the COVID-19 pandemic, the playgroup was seen as an opportunity to be a social-connector, for older people and children and their parents to be a part of “something” during a time of social isolation.

There is a clear gap between face-to-face intergenerational program models and their translation to virtual environments. While the power of technology is clear, as is its potential to encourage intergenerational interactions, there needs to be stronger understandings about how technology can redefine opportunities. There is a risk of using technology as a substitution or modification to existing face-to-face social practices without considering how we can fundamentally transform an experience to benefit all participants. A clear rationale for the adoption of technology devices and platforms is essential to ensure they are used to their full potential, ensuring users are enabled to fully participate and experience associated benefits.

The pilot program evaluated here provides important lessons and guideposts on how to transform IGPs through virtual interactions aimed at reducing social isolation. This evaluation prompts critical reflection by posing the following questions: How is play theorized to underpin IGP design and implementation? How might virtual IGPs more authentically embrace and facilitate meaningful social connection and interaction? How might a virtual design enable all participants to leverage technology through co-design processes that may engage and empower individuals in the IGP experience?

Limitations

We recognize a limitation in our research was the inability to interview older individuals or include children’s voices in our study. This limitation arose as a consequence of the state-wide lockdown, which restricted access to these vulnerable participants.

Contribution to the field

This is the first evaluation of a virtual intergenerational playgroup program.

The evaluation adopts a wellbeing framework that is applicable to elders, parents, and young children.

Findings of this paper pose considerations for both the design and implementation features for future virtual intergenerational playgroups.

Acknowledgments

We thank Associate Professor Lyn Phillipson for sharing her expertise and offering her invaluable assistance throughout the evaluation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aked, J. (2011). Five ways to wellbeing: New applications, new ways of thinking. New Economics Foundation.

- Australian Government. (n.d.). About Residential Aged Care. Retrieved March 27, 2024, from: https://www.health.gov.au/our-work/residential-aged-care/about-residential-aged-care#:~:text=Residential%20respite%20care-,What%20is%20residential%20aged%20care%3F,residential%20care%20to%20eligible%20people

- Barbosa Neves, B., Sanders, A., & Kokanović, R. (2019). “It’s the worst bloody feeling in the world”: Experiences of loneliness and social isolation among older people living in care homes. Journal of Aging Studies, 49, 74–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2019.100785

- Chee, S. Y. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic: The lived experiences of older adults in aged care homes. Millennial Asia, 11(3), 299–317. https://doi.org/10.1177/0976399620958326

- Cloutier-Fisher, D., Kobayashi, K., & Smith, A. (2011). The subjective dimension of social isolation: A qualitative investigation of older adults’ experiences in small social support networks. Journal of Aging Studies, 25(4), 407–414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2011.03.012

- Dadich, A., & Spooner, C. (2008). Evaluating playgroups: An examination of issues and options. The Australian Community Pscyhologist, 20(1), 95–104.

- Davis, H., Vetere, F., Gibbs, M., & Francis, P. (2012). Come play with me: Designing technologies for intergenerational play. Universal Access in the Information Society, 11(1), 17–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-011-0230-3

- Gerritzen, E. V., Hull, M. J., Verbeek, H., Smith, A. E., & de Boer, B. (2020). Successful elements of intergenerational dementia programs: A scoping review: Research. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships, 18(2), 214–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/15350770.2019.1670770

- Gualano, M. R., Voglino, G., Bert, F., Thomas, R., Camussi, E., & Siliquini, R. (2018). The impact of intergenerational programs on children and older adults: A review. International Psychogeriatrics, 30(4), 451–468. https://doi.org/10.1017/S104161021700182X

- Haslam, C., Cruwys, T., Haslam, S. A., & Jetten, J. (2015). Social connectedness and health. In N. A. Pachana (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Geropsychology (pp. 1–10). Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-080-3_46-2

- Hernandez, G. B. R., Murray, C. M., & Stanley, M. (2020). An intergenerational playgroup in an Australian residential aged-care setting: A qualitative case study. Health & Social Care in the Community, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13149

- Kervin, L., Phillipson, L., Nielsen-Hewett, C., Mantei, J., & Verenikina, I. (2019-2021). Play connections. A project in connections for life with dementia (led by L Phillipson). Global Challenges Keystone Project UOW.

- Khosravi, P., Rezvani, A., & Wiewiora, A. (2016). The impact of technology on older adults’ social isolation. Computers in Human Behavior, 63, 594–603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.092

- Low, L.-F., Russell, F., McDonald, T., & Kauffman, A. (2015). Grandfriends, an intergenerational program for nursing-home residents and preschoolers: A randomized trial. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships, 13(3), 227–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/15350770.2015.1067130

- Lu, L.-C., Lan, S.-H., Hsieh, Y.-P., & Lan, S.-J. (2020). Effectiveness of intergenerational participation on residents with dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nursing Open, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.919

- McLean, K., Edwards, S., & Mantilla, A. (2020). A review of community playgroup participation. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 45(2), 155–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/1836939120918484

- Ni, Z., Liu, C., Wu, B., Yang, Q., Douglas, C., & Shaw, R. J. (2018). An mHealth intervention to improve medication adherence among patients with coronary heart disease in China: Development of an intervention. International Journal of Nursing Sciences, 5(4), 322–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnss.2018.09.003

- O’Sullivan, A., Fredericks, T., Blacklaw, A., Kervin, L., Phillipson, L., Neilsen-Hewett, C., Mantei, J., & Verenikina, I. (2021). Play groups for all ages: A handbook for understanding and implementing intergenerational playgroups for wellbeing. UOW.

- Park, D. C., Lodi-Smith, J., Drew, L., Haber, S., Hebrank, A., Bischof, G. N., & Aamodt, W. (2014). The impact of sustained engagement on cognitive function in older adults: The synapse project. Psychological Science, 25(1), 103–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613499592

- Playgroup Australia. (2016). Playgroup Australia. Retrieved from: https://playgroupaustralia.org.au

- Short‐DeGraff, M. A., & Diamond, K. (1996). Intergenerational program effects on social responses of elderly adult day care members. Educational Gerontology, 22(5), 467–482. https://doi.org/10.1080/0360127960220506

- Skropeta, C. M., Colvin, A., & Sladen, S. (2014). An evaluative study of the benefits of participating in intergenerational playgroups in aged care for older people. BMC Geriatrics, 14(1), 1–11. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/1471-2318-14-109

- van Vliet, D., Persoon, A., Bakker, C., Koopmans, R. T. C. M., de Vugt, M. E., Bielderman, A., & Gerritsen, D. L. (2017). Feeling useful and engaged in daily life: Exploring the experiences of people with young-onset dementia. International Psychogeriatrics, 29(11), 1889–1898. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610217001314

- Williams, S., Renehan, E., Cramer, E., Lin, X., & Haralambous, B. (2012). ‘All in a day’s play’ – an intergenerational playgroup in a residential aged care facility. International Journal of Play, 1(3), 250–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/21594937.2012.738870

- Wu, B. (2020). Social isolation and loneliness among older adults in the context of COVID-19: A global challenge. Global Health Research and Policy, 5(1), 27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41256-020-00154-3