?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Intergenerational programs innovate constantly, but tools to evaluate them lag. Measures vary across programs and usually concentrate on outcomes without attending to programming dimensions that could influence results. Such features limit generalizability and comprehension of the mechanisms by which intergenerational programs achieve their objectives. Building on theory and evidence, we developed an evaluation tool for practitioners and researchers to use as a standalone evaluation tool or in conjunction with other measures. The current paper presents results of a Delphi study used to refine the Intergenerational Program Evaluation Tool (IPET) and establish its face and content validity. Results reinforce preexisting scholarship identifying the IPET as a reliable, valid tool that will help intergenerational scholars promote evidence-based practices and assess their impact on varied goals pursued through shared programming. We describe potential uses of the tool and next steps to advance its adoption through implementation research and psychometric assessment.

Introduction

Intergenerational programs linking young and older persons are constantly evolving, including shifts to remote programming during the height of COVID-19 (e.g., Jarrott et al., Citation2022), incorporation of the latest technology (Leedahl et al., Citation2019), and programs that stretch from the nursery (Radford et al., Citation2016) to the workplace (Pitt-Catsouphes et al., Citation2013). The evidence of their impact, however, lags behind program innovation (Jarrott, Scrivano, et al., Citation2021; Lee et al., Citation2020), creating a drag on program sustainability and replication (Canedo-García et al., Citation2017).

Researchers use a variety of methods to evaluate progress toward diverse goals pursued with intergenerational programs (e.g., Canedo-García et al., Citation2017; Jarrott, Scrivano, et al., Citation2021). Sally Newman, a founder of the intergenerational field, used structured observations (Newman & Ward, Citation1993) and interviews (Newman et al., Citation1997) as early as 1985 (Marks et al., Citation1985). Including work by Newman and colleagues, qualitative as well as quantitative measures consistently indicate that outcomes are generally positive (Jarrott, Citation2011; Lou & Dai, Citation2017). For example, recent studies determined that teens who joined intergenerational community programs demonstrated improvements in self-efficacy compared to age peers without such intergenerational opportunities (Murayama et al., Citation2022).

Less commonly found in intergenerational program evaluations are indicators of the procedures or mechanisms that facilitated change (Jarrott, Scrivano, et al., Citation2021; Laging et al., Citation2022). An exception can be found in the report of a video ethnographic study; researchers used visual transcripts to code facilitators and barriers to engagement (Kirsnan et al., Citation2022). Findings indicated that activities supported development of close relationships when facilitated with intergenerational pairs to encourage conversation. Themes of Kirsnan and colleagues’ work are echoed in a recent scoping review that associated practice strategies with program outcomes, such as preparing activity leaders and participants and incorporating mechanisms of friendship (Jarrott, Turner, et al., Citation2021).

We offer a new measure, the Intergenerational Program Evaluation Tool (IPET), intended to characterize some of the ways intergenerational programs contribute to measured outcomes. The measure reflects the authors’ belief that the goals of any intergenerational program are achieved through relationships; thus, diverse outcomes can be facilitated with intergenerational programs if positive intergenerational ties are supported. The IPET represents a measure revised through a multi-stage process, concluding with a Delphi panel of intergenerational experts, which is the focus of the current paper.

Literature review

Diverse health, education, and recreation professionals incorporate intergenerational strategies to achieve varied goals for participating youth and older adults. For example, Experience Corps research associated older adult volunteer support of elementary students with significant improvements in students’ reading performance, personal responsibility, and decision making (Porowski et al., Citation2019). Experience Corps volunteers with two years’ program experience demonstrated fewer depressive symptoms and functional limitations than members of a comparison group.

In care settings, intergenerational programming has supported a range of behavioral, affective, learning, and health outcomes (Galbraith et al., Citation2015; Laging et al., Citation2022), such as improved communication for youth (Brownell, Citation2008) and enhanced nursing home adaptation among older adult participants (Kim & Lee, Citation2018). The workplace has also been identified as an opportunity for intergenerational programs as life expectancy and workforce participation have increased. Approaches such as Gerhardt and colleagues’ gentelligence (Citation2021) emphasize the value of age diversity within the workplace and offer strategies to reduce conflict and build positive intergenerational ties that advantage individual employees and their employer.

Despite predominantly positive outcomes (Galbraith et al., Citation2015; Jarrott, Scrivano, et al., Citation2021; Laging et al., Citation2022), intergenerational practitioners, advocates, and researchers remain frustrated by the limited resources available to support high-quality outcomes research in this arena. Concerns about intergenerational research studies, documented repeatedly in the literature (e.g., Laging et al., Citation2022; Lee et al., Citation2020; Scrivano & Jarrott, Citation2023, November 10), include small sample sizes, posttest only design, absence of standardized measures, and inability to distinguish contextual influences on outcomes. While examples of studies employing exemplary research evaluation methods can be found (e.g., Gruenewald et al., Citation2016), documentation of the myriad programs falling under the umbrella “intergenerational” seems inherently constrained. A profile of intergenerational programs in the US reveals some of the challenges evaluators face in collecting and synthesizing data (Jarrott & Lee, Citation2022). For example, the number of participants can range from single digits to thousands, which would necessarily impact evaluation methods. The diversity of program participants also plays a role in documentation of outcomes; evaluation tools need to be responsive to cultural contexts (Patton, Citation2023).

Practitioners understand the need for program evaluation; a United States sample identified demonstrating impact of their intergenerational services as their number one challenge (Jarrott & Lee, Citation2022). Providers recognized that photos and videos of young and older people enjoying time together are valuable but do not, on their own, translate the impact of programming to potential participants, employees, or funders. In addition to the challenges described above, organizations may face barriers such as availability and training of staff to conduct evaluations, the cost of hiring a professional evaluator, and availability of evaluation resources specific to intergenerational programs (Herbert, Citation2014). Research tools, like the Intergenerational Observation Scale (Jarrott & Smith, Citation2011), which informed the IPET, are often cumbersome to use, limiting their utility to practitioners seeking to understand and improve their programs.

The IPET is intended to be useful on its own or in conjunction with other outcome measures, thereby helping to reduce the lag between intergenerational program innovation and evaluation. If the measure proves psychometrically sound and practical to adopt, it could be used by many intergenerational programs, thereby allowing for greater sample sizes and generalizability across participants and programs.

IPET background

Reflecting the belief that positive intergenerational relationships can be the outcome of intergenerational programs or the means of achieving other desired outcomes, our work draws on Allport’s (Citation1954) and Pettigrew’s (Citation1998) theory of intergroup contact. According to the theory, positive intergroup contact is more likely to occur when characterized by stakeholder support, equal group status of participants, collaboration on a common goal, and mechanisms of friendship. A second influential theory, environmental press (Lawton, Citation1982), depicts the influence of modifiable physical and social environmental features on individual performance, thereby linking participant well-being to the actions of persons such as program leaders. Research linking higher levels of intergenerational interaction with activity leaders’ use of practices reflecting these theories demonstrated their value to intergenerational practice (Jarrott & Smith, Citation2011). Subsequently, researchers conceptualized the practice strategies into intergenerational training materials and a corresponding measure, the Best Practices Checklist, that could be used by researchers and practitioners alike.

The Best Practices Checklist, designed to be completed for an individual activity (Jarrott, Turner, et al., Citation2021; Juckett et al., Citation2021), achieved acceptable inter-rater reliability (IRR; Cohens K > .60) on all but one item (K = .35) between practitioners and observers who completed training on implementing and assessing use of the best practices (Juckett et al., Citation2021). As well, when activity leaders used more of the pairing and person-centered strategies (e.g., when leaders discussed the activity in relation to participant experiences to encourage intergenerational interaction), both children and older adult participants demonstrated higher levels of intergenerational interaction, as measured with the Intergenerational Observation Scale, compared to their individual means (see Jarrott, Turner, et al., Citation2021), which notes predominant social behavior of youth and older adult participants during the activity.

Despite indicators of the Best Practices Checklist reliability, several drivers led us to revise it. First, some items on the Checklist were almost never used or were almost always used (Juckett et al., Citation2021), suggesting that they did little to differentiate outcomes. Second, interviews with practitioners who used the Best Practices Checklists indicated that some items duplicated each other, and other items could be more precisely worded (Juckett et al., Citation2021). Third, multi-level modeling indicated that some but not all items of the Best Practices Checklist predicted higher levels of intergenerational interaction (Jarrott, Turner, et al., Citation2021). Taken together, these data sources suggested that some items might be eliminated due to poor predictive ability and others might be made clearer, contributing to a shorter and more reliable, valid Best Practices Checklist. Finally, the Best Practices Checklist had to be used in conjunction with another measure to link activity leader practices with participant outcomes, such as behavioral and affective response captured by the Intergenerational Observation Scale, a complex observation research instrument (Jarrott & Smith, Citation2011). Thus, we revised the Best Practices Checklist into the IPET to represent both activity leader practices and participant responses to those strategies.

We designed the Best Practices Checklist to be utilized in settings engaging different groups of youth and older participants, but we had only tested it with preschoolers, usually in shared site programs with older care recipients. Thus, after using our data to create the IPET, we conducted a Delphi panel with researchers and practitioners experienced in intergenerational work with diverse groups to help ensure the IPET’s utility in diverse settings.

A Delphi panel engages panelists with topical expertise to provide anonymous feedback and generate ideas related to a product, such as a framework, protocol, or instrument (Hsu & Sandford, Citation2007). Through multiple rounds, researchers present their product to the panel, gather and synthesize evaluative feedback, and revise the product accordingly. Researchers typically specify in advance a maximum number of rounds that panelists will complete or a level of consensus that must be achieved for the product to be accepted (Diamond et al., Citation2014). The current paper presents the Delphi study that resulted in the current IPET (see Appendix A).

Methods

Participants (panel selection)

For the current study, an expert panel of intergenerational researchers and practitioners served as Delphi panelists. The first author and collaborators at Generations United identified potential respondents (OSU IRB#2018E0058); requirement of signed consent from participants was waived by the authorizing ethics review board. Research experts came from university settings, primarily in the United States; practitioners included a mix of United States program directors and activities leaders. The first author sent e-mail invitations describing the project goals and time frame, asking individuals to share their expertise to evaluate and shape the IPET for use with diverse intergenerational programs. Of 30 professionals invited to participate, six declined the invitation for varied reasons (e.g., pending retirement), and three did not respond to multiple e-mail invitations. Twenty-one professionals agreed to participate as Delphi panelists with an even distribution between researchers and practitioners. Because they were asked to provide feedback on a topic related to their professional expertise, participants were not required to complete a consent form.

Materials and procedure

Step one of a Delphi study typically invites panelists to set or agree upon criteria against which to evaluate the product, in this case the IPET. We described the intended users and purpose of the IPET, sharing a set of 19 potential evaluation criteria representing dimensions of: (a) relevance of criteria to intergenerational programs, (b) criteria comprehensiveness, and (c) item construction. From April to May 2019 panelists accessed a Qualtrics link to evaluate whether each criterion was essential to evaluate an intergenerational activity, using dichotomous yes/no ratings and offering comments or suggestions. A summary report of the ratings and the resultant criteria were shared with panelists.

With evaluation criteria established, Delphi panelists next accessed a Qualtrics link in June–July 2019 and completed the Round 1 rating of the IPET against the criteria using a 4-point Likert scale (1=poor, 2=fair, 3=good, 4=excellent). Panelists were also invited to provide qualitative feedback on the IPET as a whole and related to each criterion. The first author made follow-up contact with panelists as needed to check understanding of open-ended comments. Ratings and qualitative feedback informed revisions to the IPET. A summary of raters’ Round 1 feedback and resultant changes were shared with panelists.

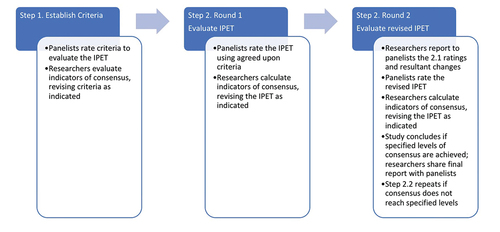

Panelists then completed Round 2 ratings in August 2019. They were provided with the original version of the IPET, for reference, and the revised IPET. Panelists evaluated the revised version using a Qualtrics survey. We again revised the IPET, sharing summary feedback and the final IPET with panelists. graphically represents the Delphi process.

The means by which Delphi researchers determine their product is acceptable varies widely (Diamond et al., Citation2014). Some investigators predefine criteria rating agreement levels needed to accept their product; alternately, they may specify a maximum number of rounds they will complete before finalizing the product (Boulkedid et al., Citation2011). In the current study, we planned to conduct a minimum of two rounds of evaluation and defined consensus as achieving high agreement for each criterion using analyses described in the following section. We also used qualitative comments to guide revisions to the IPET.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated using panelists’ criteria rating scores. Reflecting the most common measure of central tendency in Delphi studies (Boulkedid et al., Citation2011), median scores were calculated for each criterion. A median of 3 “good” was set to indicate minimum acceptable criterion rating. The interquartile range (IQR), or the difference between scores at the first and third quartile of ratings, was calculated as an indicator of variance for each criterion (Campbell et al., Citation2021), with a smaller IQR indicating lower variance and closer agreement among panelists. These two indicators were used to categorize level of agreement for each criterion (Campbell et al., Citation2021). Level of agreement was coded as follows: (a) high – median score of 4 and IQR , (b) moderate – median score of 3 and IQR

, or (c) low – median score of 2 and IQR > 2. We considered the IPET accepted when each criterion achieved high agreement.

Open-ended responses allowed panelists to provide qualitative feedback on each item, criteria of relevance, and construction of items. Responses across the data set were compiled to make sense of common themes and followed six phases of thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2014). The first author became familiar with the data (phase 1), generated initial codes (phase 2), and then searched for themes (phase 3). The patterns of responses from initial codes shifted into themes related to individual items and the overall IPET. Then the first and second author reviewed the potential themes (phase 4) and defined them (phase 5). Themes were used in conjunction with the measures of central tendency, variance, and agreement to modify the IPET following each round of criteria rating by Delphi panelists.

Results

Evaluation criteria rating form

Each of the 19 proposed evaluation criteria was endorsed by 75–100% of the 20 responding panelists (95%) as a critical indicator of the quality of an intergenerational program evaluation tool. Ratings and qualitative feedback led to a small number of revisions, including modifications to eliminate jargon, reduce potential overlap, improve item construction, enhance item clarity, and more fully represent participant experiences. As a result, the criteria rating form consisted of 20 items against which the IPET was judged (see ).

Table 1. Qualitative feedback themes and resultant changes to the IPET.

Rating the IPET

Consensus, which we defined as high agreement on each criterion, was achieved after the second round of Delphi ratings of the IPET. Round 1 ratings were completed by 19 panelists (90%). Their ratings of the initial version of the IPET against each criterion were favorable (Median 3; IQR = 1; Level of agreement = medium-high). Panelists who assigned lower ratings to a criterion often provided qualitative feedback regarding potential modifications. The qualitative responses yielded three themes from Round 1 and an additional theme in Round 2 (see ). Panelist responses to open-ended questions revealed a theme to use clearer language by avoiding jargon (e.g., “what is social history?” and “role-appropriate doesn’t capture ‘developmentally appropriate’”). The second theme focused on revising the IPET to reflect diverse program contexts, such as incorporating more inclusive language reflecting participant diversity (e.g., “[ask] if any modifications would need to be made to accommodate cultural/language needs”). Finally, panelist responses reflected a third theme to add content to improve quality and utility of the IPET. For example, creating a user guide, adding space for qualitative notes to individual items, and adding an affective quality rating for participant behavior.

Taken together, the quantitative criteria ratings and qualitative themes led investigators to make modifications. Resultant modifications to IPET items included: (a) using jargon-free terminology, (b) depicting participant diversity (items 2 and 3 of the current version), and (c) adding an answer option of “not applicable” to items 5 and 9. We added two Likert-scale items representing predominant affect of youth and older adult participants to represent participant experiences more fully. We added space for respondents to clarify IPET item ratings and reflect on the activity, and we expanded directions for using the IPET.

The IPET rated in Round 2 earned higher ratings for each criterion with 17 panelists (81%), which are presented in . Ratings of each criterion achieved a high level of agreement (median score = 4 and IQR ≤ 1). Qualitative feedback on the revised IPET informed final revisions to the tool. Specifically, continued feedback about inclusivity of diverse participants led us to modify youth and older adult participant illustrations to depict racial and ethnic diversity (item 13). presents Round 2 indicators for each criterion, including the percentage of scores equal to or greater than 3, the interquartile range, and the resultant level of agreement for each criterion.

Table 2. Round 2 IPET criteria rating indicators.

Ratings of each criterion achieved a high level of agreement (median score = 4 and IQR ≤ 1). Qualitative feedback on the revised IPET informed final revisions to the IPET. Specifically, continued feedback about inclusivity of diverse participants led us to modify youth and older adult participant illustrations to depict racial and ethnic diversity (item 13). presents Round 2 indicators for each criterion, including the percentage of scores equal to or greater than 3, the interquartile range, and the resultant level of agreement for each criterion.

Discussion

In response to the identified need for intergenerational program evaluation tools that can be adopted by practitioners and researchers (Jarrott & Lee, Citation2022), we endeavored to create a valid, reliable measure of intergenerational implementation practices and participant responses. Knowing that intergenerational programs are highly variable, the IPET was created for use with programs engaging diverse ages, abilities, and numbers of younger and older participants who engage in varied programming conducted in diverse settings. Findings from studies using precursors of the IPET (i.e., The Best Practices Checklist and the Intergenerational Observation Scale) that suggest reliability (Juckett et al., Citation2021) and criterion validity (Jarrott, Turner, et al., Citation2021) informed the IPET creation. The Delphi study presented here supports the face and content validity of the new instrument. In this section we address implications of our findings, strengths and limitations of the Delphi study, and next steps.

Delphi panelists representing intergenerational practice and research expertise endorse the dimensions essential to evaluation of intergenerational programs – relevance, comprehensiveness, and construction of items. Items’ relevance and comprehensiveness highlight the diversity of intergenerational programs, which are implemented in varied settings, with participants of richly diverse backgrounds and abilities, variable staffing, and fabulously diverse content. Panelists understand that the IPET will be most useful if it captures the key domains of intergenerational programming.

In addition to comprehensive representation of core intergenerational program dimensions, panelists endorse the item construction criteria reflecting the usability of the IPET. Knowing that researchers and practitioners with varied training and resources evaluate intergenerational programs, a useful tool is free of jargon, bias, complex directions, excessive answer categories or open-ended prompts, and immoderate length. An instrument to be used by interdisciplinary professionals must be acceptable and feasible if it is to be adopted (e.g., Proctor et al., Citation2011).

Turning to the results of the IPET evaluation, the instrument achieved high marks for each criterion, and ratings improved from Round 1 to Round 2 with data-informed revisions. The high level of agreement supports the measure’s face and content validity. Panelists endorse the IPET as a measure that comprehensively represents key dimensions needed to evaluate intergenerational programming and that can feasibly be adopted by intended users. The instrument may prove useful to practitioners and researchers alike. On a day-to-day basis, practitioners can use the IPET to remind them of best practices to use and reflect on an activity after it has concluded. It may prove particularly useful to practitioners when an inexperienced staff member begins leading programming, when changes are made to programming, or if participant engagement drops off.

The use of more IPET practices should correspond with higher levels of intergenerational interaction (Jarrott, Turner, et al., Citation2021) and more positive affect (see Galbraith et al., Citation2015). IPET data can help practitioners evaluate young and older participants’ engagement in and response to intergenerational programming – a useful outcome indicator on its own. The IPET may also be used in conjunction with other measures reflecting programming goals. For example, if the goal for older adult participants of an intergenerational program is to reduce feelings of loneliness, the association between data gathered with the IPET and repeated measures of the UCLA loneliness scale (Russell, Citation1996) could be studied. Researchers may associate the use of specific IPET practices or the implementation of more IPET practices with changes in participant loneliness scores.

Strengths and limitations

The Delphi methodology represents a strength of our study to refine the IPET. Panelists were able to provide their feedback in an efficient manner without the influence of other panelists (Hsu & Sandford, Citation2007). The even representation of intergenerational research and practice experts who work with diverse participants and program content is a strength, highlighting important considerations such as feasibility of scale adoption by intended users and representing participant diversity in the items.

Delphi methods vary widely, and our study reflects best practices for this method (Boulkedid et al., Citation2011; Diamond et al., Citation2014). These include: (a) pre-specifying the level of agreement we would achieve and number of rounds of evaluation we would complete before accepting the IPET, (b) engaging multiple stakeholder groups as panelists, (c) reporting response rates of each round of evaluation to panelists, (d) maintaining panelist anonymity, and (e) reporting multiple indicators of central tendency and variation.

The current study also has limitations. A larger panel may have provided us with more insight into the breadth of intergenerational programs and their variations. Two panelists, one researcher and one practitioner, who indicated interest in participation and who evaluated the criteria rating form did not evaluate the IPET. However, our 17 panelist sample (Round 2 evaluation of the IPET) matches the median sample size identified in the Boulkedid et al. (Citation2011) report on 76 Delphi panels. Finally, a best practice identified in a scoping review of Delphi studies that ours lacked includes reporting on panelists’ years of experience (Boulkedid et al., Citation2011). Being familiar with the panelists, we know that their experience ranges from several years to decades in the intergenerational field, but we did not ask panelists to specify this information.

Next steps

Next steps involve planning for and then testing implementation of the IPET in the field. Related research should address dimensions of implementation and psychometric indicators of the IPET.

Starting with factors influencing the adoption of the IPET, an implementation framework can guide us. First, we want to establish that the IPET is appropriate, acceptable, and feasible to intended users (Proctor et al., Citation2011), intergenerational practitioners, and researchers. Studies designed to capture factors influencing uptake of an intervention or assessment process, such as those presented in the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR: Damschroeder et al., Citation2009), are particularly valuable for intergenerational programs, which are frequently limited by these factors (Jarrott & Lee, Citation2022). For example, relative priority, a sub-construct of the implementation climate factor of the CFIR model has been identified as a limiter by intergenerational program leaders when they perceive that other tasks take a higher priority than program documentation or even programming itself (Weaver et al., Citation2019). A mixed methods pre-implementation study would invite respondents to rate the IPET on these constructs and describe expected facilitators and barriers to IPET adoption in their setting, which could then be compared to later experiences with the IPET by adopters (Proctor et al., Citation2011).

Turning to the tool’s psychometric properties, we aim to establish inter-rater reliability by having multiple trained observers complete the IPET for the same activity to analyze the level of agreement. To test criterion validity, the IPET should be used in conjunction with other measures relevant to intergenerational programs and the core dimensions of the IPET. The IPET reflects our belief that intergenerational program outcomes are achieved through positive intergenerational interaction (IPET items 13 and 14), which is supported through implementation of the strategies depicted in IPET items 1–10. Thus, analyses could determine the association between scores on IPET items 1–10 and items 13 and 14.

In the future, convergent validity can be established by a positive correlation between IPET constructs and other measures of similar constructs, while divergent validity can be indicated by a negative association between distinct and unrelated constructs. To our knowledge a reliable, valid measure of intergenerational activity leader practices did not previously exist, which provided the inspiration to develop the IPET. Epstein and Boisvert’s (Citation2006) measure associates teacher behaviors with responses to intergenerational programs over a two-week observation period following teacher training, but the scale is specific to early childhood settings, has not been validated, and appears not to be currently in use. Convergent and divergent validity of IPET items 13–14 could be estimated by administering them with other instruments. For example, the Menorah Park Engagement Scale could be used with item 13 (Judge et al., Citation2000) to look for correspondence between coded observations of participant behavior. The Apparent Affect Rating Scale (Lawton et al., Citation1996) could be used with item 14 to address different affective states. However, because intergenerational programs engage participants of varied ability, validity of items 13–14 may need to be established separately with measures appropriate for the focal participant groups. To illustrate, the scales mentioned above (Judge et al., Citation2000; Lawton et al., Citation1996) were validated with frail older adults, and different measures might need to be used with healthy older adults or with youth.

Additional steps need to be taken before the IPET can be promoted for wide-scale adoption in diverse intergenerational contexts. The Delphi study results support continued exploration of the instrument’s utility for researchers and practitioners alike.

Conclusion

Extending the work that Dr. Sally Newman began in the 20th century, the IPET represents an effort to create a valid, reliable evaluation tool that is accessible to intergenerational practitioners and researchers alike. Studies by our and other research teams repeatedly highlight the importance of the activity leader to intergenerational program outcomes (e.g., Varma et al., Citation2015). Activity leaders benefit from support that promotes their intergenerational practice skills (e.g., Juckett et al., Citation2021). The IPET incorporates practices activity leaders can use to promote positive intergenerational relationships, which are captured in the IPET and which, in turn, are the method by which other programmatic objectives can be obtained (Jarrott, Scrivano, et al., Citation2021). Activity leaders who learn to use the IPET may find it useful for ongoing documentation or focused evaluation practice.

Researchers can also benefit from the IPET. As new types of intergenerational programs continue proliferating, a measure designed for use across participant, organizational, and content variations offers needed flexibility. Researchers seeking to understand the impact of intergenerational programs on myriad outcomes of interest can better understand their findings if they can interpret them with evidence of the strategies used by activity leaders and the nature of intergenerational contact in the setting.

The Delphi study of the IPET represents a next step toward providing an evidence-based evaluation tool that is sorely needed within the field. Subsequent evaluation of the tool’s acceptability by intended users and indicators of reliability and validity will yield a resource of value to the richly diverse intergenerational programs currently in operation and yet to be developed.

Contribution to the Field

The current study advances the field of intergenerational program research by:

1. Identifying key dimensions that should inform selection of evaluation tools for use with diverse intergenerational programs.

2. Presenting the research that informed the freely available Intergenerational Program Evaluation Tool, which was designed for use by intergenerational practitioners and researchers.

3. Describing how the resultant tool can be used in conjunction with other outcome measures to demonstrate mechanisms by which results are achieved.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (721.3 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, [SJ]. The data are not publicly available due to the authorized IRB protocol (OSU IRB#2018E0058).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/15350770.2024.2349927

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Addison-Wesley.

- Boulkedid, R., Abdoul, H., Loustau, M., Sibony, O., Alberti, C., & Wright, J. M. (2011). Using and reporting the Delphi method for selecting healthcare quality indicators: A systematic review. Public Library of Science ONE, 6(6), e20476. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0020476

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2014). What can “thematic analysis” offer health and wellbeing researchers? International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 9(1), 26152. https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v9.26152

- Brownell, C. (2008). An intergenerational art program as a means to decrease passive behaviors in patients with dementia. American Journal of Recreation Therapy, 7(3), 5–12. https://doi.org/10.5055/ajrt.2008.0016

- Campbell, M., Stewart, T., Brunkert, T., Campbell-Enns, H., Gruneir, A., Halas, G., Hoben, M., Scott, E., Wagg, A., & Doupe, M. (2021). Prioritizing supports and services to help older adults age in place: A Delphi study comparing the perspectives of family/friend care partners and healthcare stakeholders. Public Library of Science ONE, 16(11), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0259387

- Canedo-García, A., Garcia-Sánchez, J., & Pacheco-Sanz, D. (2017). A systematic review of the effectiveness of intergenerational programs. Frontiers in Psychology, 8. Article 1882. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01882

- Damschroeder, L. J., Aron, D. C., Keith, R. E., Kirsh, S. R., Alexander, J. A., & Lowery, J. C. (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 4(1), 50. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-4-50

- Diamond, I. R., Grant, R. C., Feldman, B. M., Pencharz, P. B., Ling, S. C., Moore, A. M., & Wales, P. W. (2014). Defining consensus: A systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67(4), 401–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.12.002

- Epstein, A. S., & Boisvert, C. (2006). Let’s do something together: Identifying effective components of intergenerational programs. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships, 4(3), 87–109. https://doi.org/10.1300/J194v04n03_07

- Galbraith, B., Larkin, H., Moorhouse, A., & Oomen, T. (2015). Intergenerational programs for persons with dementia: A scoping review. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 58(4), 357–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2015.1008166

- Gerhardt, M., Nachemson-Ekwall, J., & Fogel, B. (2021). Gentelligence: The revolutionary approach to leading an intergenerational workforce. Rowan & Littlefield.

- Gruenewald, T. L., Tanner, E. K., Fried, L. P., Carlson, M. C., Xue, Q. L., Parisi, J. M., Reebok, G. W., Yarnell, L. M., & Seeman, T. E. (2016). The baltimore experience corps trial: Enhancing generativity via intergenerational activity engagement in later life. Journals of Gerontology, 71(4), 661–670. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbv005

- Herbert, J. H. (2014). Towards program evaluation for practitioner learning: Human service practitioners’ perceptions of evaluation. Australian Social Work, 68(4), 438–452. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2014.946067

- Hsu, C., & Sandford, B. A. (2007). The delphi technique: Making sense of consensus. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 12(10), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.7275/pdz9-th90

- Jarrott, S. E. (2011). Where have we been and where are we going? Content analysis of evaluation research of intergenerational programs. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships, 9(1), 37–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/15350770.2011.544594

- Jarrott, S. E., & Lee, K. (2022). Shared site intergenerational programs: A national profile. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 35(3), 393–410. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420.2021.2024410

- Jarrott, S. E., Leedahl, S. N., Shovali, T. E., DeFries, C., DelPo, A., Estus, E., Ganji, C., Hasche, L., Juris, J., MacInnes, R., Schilz, M., Scrivano, R. M., Steward, A., Taylor, C., & Walker, A. (2022). Intergenerational programming during the pandemic: Transformation during (constantly) changing times. Journal of Social Issues, 78(4), 1038–1065. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12530

- Jarrott, S. E., Scrivano, R. M., Park, C., & Mendoza, A. (2021). Implementation of evidence-based practices in intergenerational programming: A scoping review. Research on Aging, 43(7–8), 283–293. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027521996191

- Jarrott, S. E., & Smith, C. L. (2011). The complement of research and theory in practice: Contact theory at work in non-familial intergenerational programs. The Gerontologist, 51(1), 112–121. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnq058

- Jarrott, S. E., Turner, S. G., Juris, J., Scrivano, R. M., Weaver, R. H., & Meeks, S. (2021). Program practices predict intergenerational interaction among children and older adults. The Gerontologist, 62(3), 385–396. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnab161

- Jarrott, S. E., Turner, S. G., Naar, J. J., Juckett, L. M., & Scrivano, R. M. (2021). Increasing the power of intergenerational programs: Advancing an evaluation tool. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 41(3), 763–768. https://doi.org/10.1177/07334648211015459

- Juckett, L., Jarrott, S. E., Naar, J. J., Scrivano, R., & Bunger, A. C. (2021). Implementing intergenerational best practices in community-based settings: A pre-implementation study. Health Promotion Practice, 23(3), 473–481. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839921994072

- Judge, K. S., Camp, C. J., & Orsulic-Jeras, S. (2000). Use of montessori-based activities for clients with dementia in adult day care: Effects on engagement. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias, 15(1), 42–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/153331750001500105

- Kim, J., & Lee, J. (2018). Intergenerational program for nursing home residents and adolescents in Korea. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 44(1), 32–41. https://doi.org/10.3928/00989134-20170908-03

- Kirsnan, L., Kosiol, J., Golenko, X., Radford, K., & Fitzgerald, J. A. (2022). Barriers and enablers for enhancing engagement of older people in intergenerational programs in Australia. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships, 21(3), 360–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/15350770.2022.2065400

- Laging, B., Slocombe, G., Liu, P., Radford, K., & Gorelik, A. (2022). The delivery of intergenerational programmes in the nursing home setting and impact on adolescents and older adults: A mixed studies systematic review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 133, 104281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2022.104281

- Lawton, M. P. (1982). Competence, environmental press, and the adaptation of older people. In M. P. Lawton, P. G. Windley, & T. O. Byerts (Eds.), Aging and the environment: Theoretical approaches (pp. 33–59). Springer Publishing Company.

- Lawton, M. P., Van Haitsma, K., & Klapper, J. (1996). Observed affect in nursing home residents with Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences, 51B(1), 3–P14. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/51B.1.P3

- Leedahl, S. N., Brasher, M. S., Estus, E., Breck, B. M., Dennis, C. B., & Clark, S. C. (2019). Implementing an interdisciplinary intergenerational program using the cyber seniors© reverse mentoring model within higher education. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education, 40(1), 81–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701960.2018.1428574

- Lee, K., Jarrott, S. E., & Juckett, L. A. (2020). Documented outcomes for older adults in intergenerational programming: A scoping review. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships, 18(2), 113–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/15350770.2019.1673276

- Lou, V. W. Q., & Dai, A. A. N. (2017). A review of nonfamilial intergenerational programs on changing age stereotypes and well-being in east asia. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships, 15(2), 143–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/15350770.2017.1294427

- Marks, R., Newman, S., & Onawola, R. (1985). Latency-aged children’s views of aging. Educational Gerontology, 11(2–3), 89–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/0380127850110202

- Murayama, Y., Yamaguchi, J., Yasunaga, M., Kuraoka, M., & Fujiwara, Y. (2022). Effects of participating in intergenerational programs on the development of high school students’ self-efficacy. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships, 20(4), 406–423. https://doi.org/10.1080/15350770.2021.1952133

- Newman, S., Faux, R., & Larimer, B. (1997). Children’s views on aging: Their attitudes and values. Gerontologist, 37(3), 412–417. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/37.3.412

- Newman, S., & Ward, C. (1993). An observational study of intergenerational activities and behavior change in dementing elders at adult day care centers. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 36(4), 321–333. https://doi.org/10.2190/7pn1-l2e1-ulu1-69ft

- Patton, M. Q. (2023). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice. SAGE Publications.

- Pettigrew, T. F. (1998). Intergroup contact theory. Annual Review of Psychology, 49(1), 65–85. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.65

- Pitt-Catsouphes, M., Mirvis, P., & Berzin, S. (2013). Leveraging age diversity for innovation. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships, 11(3), 238–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/15350770.2013.810059

- Porowski, A., de Mars, M., Kahn-Boesel, E., & Rodriguez, D. (2019). Experience corps social-emotional learning evaluation. AARP Foundation. https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/aarp_foundation/2020/pdf/AARP_Foundation_Experience_Corp_Abt_SEL.pdf

- Proctor, E., Silmere, H., Raghavan, R., Hovmand, P., Aarons, G., Bunger, A., Griffey, R., & Hensley, M. (2011). Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(2), 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7

- Radford, K., Oxlade, D., Fitzgerald, A., & Vecchio, N. (2016). Making intergenerational care a possibility in Australia: A review of the Australian legislation. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships, 14(2), 119–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/15350770.2016.1160732

- Russell, D. (1996). UCLA loneliness scale (version 3): Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 66(1), 20–40. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2

- Scrivano, R. M., & Jarrott, S. E. (2023) self-directed ageism outcomes associated with ageism-reduction interventions: A scoping review [ Poster presentation]. Gerontological Society of America Annual Scientific Meeting, Tampa, FL.

- Varma, V. R., Carlson, M. C., Parisi, J. M., Tanner, E. K., McGill, S., Fried, L. P., Song, L. H., & Gruenewald, T. L. (2015). Experience corps Baltimore: Exploring the stressors and rewards of high-intensity civic engagement. The Gerontologist, 55(6), 1038–1049. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnu011

- Weaver, R., Naar, J. J., & Jarrott, S. E. (2019). Using contact theory to assess staff perspectives on training initiatives of an intergenerational programming intervention. Advance online publication. The Gerontologist, 59(4), 270–277. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnx194