Abstract

Evidence-based assessment (EBA) is foundational to high-quality mental health care for youth and is a critical component of evidence-based practice delivery, yet is underused in the community. Administration time and measure cost are barriers to use; thus, identifying and disseminating brief, free, and accessible measures are critical. This Evidence Base Update evaluates the empirical literature for brief, free, and accessible measures with psychometric support to inform research and practice with youth. A systematic review using PubMed and PsycINFO identified measures in the following domains: overall mental health, anxiety, depression, disruptive behavior, traumatic stress, disordered eating, suicidality, bipolar/mania, psychosis, and substance use. To be eligible for inclusion, measures needed to be brief (50 items or less), free, accessible, and have psychometric support for their use with youth. Eligible measures were evaluated using adapted criteria established by De Los Reyes and Langer (2018) and were classified as having excellent, good, or adequate psychometric properties. A total of 672 measures were identified; 95 (14%) met inclusion criteria. Of those, 21 (22%) were “excellent,” 34 (36%) were “good,” and 40 (42%) were “adequate.” Few measures had support for their use to routinely monitor progress in therapy. Few measures with excellent psychometric support were identified for disordered eating, suicidality, psychosis, and substance use. Future research should evaluate existing measures for use with routine progress monitoring and ease of implementation in community settings. Measure development is needed for disordered eating, suicidality, psychosis, and substance use to increase availability of brief, free, accessible, and validated measures.

Evidence-based assessment (EBA) is a cornerstone of high-quality evidence-based practice in mental health care (Hunsley & Mash, Citation2018; Jensen‐Doss, Citation2011; Youngstrom et al., Citation2017). EBA serves two key clinical functions. First, early in treatment, EBA is essential for guiding initial case conceptualization, supporting the identification of appropriate treatment targets, and guiding clinicians in the selection of evidence-based treatment strategies (Youngstrom, Choukas-Bradley, Calhoun, & Jensen-Doss, Citation2015). Second, after the initial assessment, EBA guides the monitoring of treatment progress and informs the personalization of treatment to optimize treatment success (Ng & Weisz, Citation2016; Youngstrom et al., Citation2015). Use of EBA both early in treatment and throughout the course of treatment (also referred to as measurement-based care; Scott & Lewis, Citation2015) has been associated with improved youth treatment engagement (Klein, Lavigne, & Seshadri, Citation2010; Pogge et al., Citation2001) and youth treatment response (Bickman, Kelley, Breda, de Andrade, & Riemer, Citation2011; Eisen, Dickey, & Sederer, Citation2000; Jensen-Doss & Weisz, Citation2008).

Use of EBA is particularly important when working with youth in routine and/or low-resource settings, such as community mental health clinics. In these settings, comorbidity is the norm (Southam-Gerow, Weisz, & Kendall, Citation2003; Weisz, Ugueto, Cheron, & Herren, Citation2013), so clinicians must adapt evidence-based treatment approaches often designed for single problem areas to suit the complex needs of their clients (Connor‐Smith & Weisz, Citation2003). Emerging evidence suggests that a flexible treatment approach that allows for such adaptation by tailoring the sequence of treatment techniques to address individual client needs outperforms traditional manualized treatment protocols in these settings (Weisz et al., Citation2012). Thus, EBA may have enormous potential for supporting clinical decision-making. For example, systematic assessment signaling a possible clinical deterioration can guide clinicians’ decisions to adapt or shift treatment focus (Bearman & Weisz, Citation2015; Lambert, Citation2007; Lambert et al., Citation2003; Shimokawa, Lambert, & Smart, Citation2010).

Despite the promise of EBA in usual care for youth, use is low (Jensen-Doss, Becker-Haimes, et al., Citation2018; Jensen-Doss & Hawley, Citation2010; Lyon, Dorsey, Pullmann, Silbaugh-Cowdin, & Berliner, Citation2015; Whiteside, Sattler, Hathaway, & Douglas, Citation2016). Although multiple barriers to EBA exist (Boswell, Kraus, Miller, & Lambert, Citation2015), surveys of practicing clinicians routinely demonstrate that the time and cost associated with engaging in EBA are most prohibitive (Kotte et al., Citation2016; Whiteside et al., Citation2016). Gold-standard diagnostic measures are costly, can take over three hours to administer (e.g., Kaufman et al., Citation1997; Lyneham, Abbott, & Rapee, Citation2007), and are typically non-billable services. They are therefore financially prohibitive, especially in publicly funded settings. Similarly, measurement and feedback systems, which provide an infrastructure for clinicians to regularly administer and interpret progress monitoring measures for youth, require substantial organizational investment that can be difficult to implement or sustain (Bickman et al., Citation2016; Lyon, Lewis, Boyd, Hendrix, & Liu, Citation2016). Although policy solutions to support insurance reimbursement for EBA have been proposed to circumvent the financial burden of these measures (Boswell et al., Citation2015), in the current healthcare landscape, many clinical settings cannot afford the costs associated with EBA. More research is needed on evidence-based strategies to reduce barriers to EBA implementation.

Brief, free, accessible, and validated measures to be used in EBA with youth can facilitate EBA adoption and uptake. Beidas et al. (Citation2015) conducted a review of such measures for prevalent youth mental health disorders (overall mental health, anxiety, depression, disruptive behavior, eating, bipolar, suicidality, and traumatic stress). This review yielded 20 instruments that were fewer than 50 items, free, and had at least modest psychometric support for use with youth (Beidas et al., Citation2015). An update and extension to this review is needed. First, the initial review primarily served as a clinical guide and reference for selecting measures and did not emphasize their psychometric properties. A comprehensive evaluation of the psychometric properties for identified measures is needed to inform our understanding of the current state of the science and to set an agenda for future research. Second, since the publication of this initial review, multiple repositories designed to house freely accessible measures were created, there has been an increased emphasis on developing pragmatic measures to be used in EBA (Jensen-Doss, Citation2015), and implementation efforts focused on EBA for youth are underway (e.g., Jensen-Doss, Ehrenreich-May, et al., Citation2018; Lyon et al., Citation2019). Related, the initial search was conducted prior to the publication of DSM-5 (American Psychological Association, Citation2013); in the past several years, new measures may have been developed to match updated diagnostic criteria and new diagnostic categories (e.g., avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder, disruptive mood dysregulation disorder). Finally, the original review did not include any measures related to the assessment of substance use. Given the growing public health crisis related to substance abuse in adolescence (Degenhardt, Stockings, Patton, Hall, & Lynskey, Citation2016), it is important to extend the initial review to cover measures of youth substance use.

This systematic review provides a comprehensive Evidence Base Update for brief, free, and accessible EBA measures for use in youth mental health, guided by criteria set forth by De Los Reyes and Langer (Citation2018; see ). The primary objectives of this review are to provide: (a) an overview of the state of the science for currently available brief, free, and accessible measures, (b) recommendations for areas of priority for future research, and (c) an expanded clinical resource for those seeking to implement EBA in community settings. We paid particular attention to evaluating measures with regard to their psychometric properties to routinely monitor treatment progress, in addition to reliability and validity, since mental health care is increasingly moving toward requiring clinicians and organizations to demonstrate the quality of care provided.

Table 1 Rubric for Evaluating Norms, Validity, and Utility

Methods

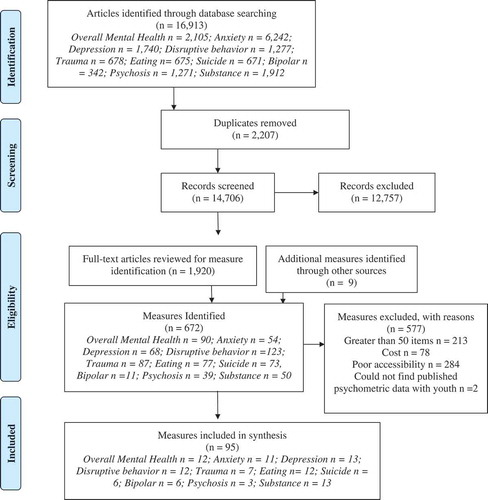

Our review process built on procedures used by Beidas et al. (Citation2015) in their initial review, which was conducted in 2012–2013. Search criteria were expanded and updated to include DSM-5 language. We employed a more rigorous three-stage systematic review process that included: (1) measure identification, (2) measure eligibility assessment, and (3) evaluation of measure psychometric properties. illustrates the PRISMA flow diagram.

Measure Identification

We searched PubMed and PsycINFO in October 2018 using the following search terms: (“disorder name/type”) AND (“instrument” OR “survey” OR “questionnaire” OR “measure” OR “assessment”) AND (“psychometric or “measure development” or “measure validation”). Each disorder name/type was searched individually, using the following terms: overall mental health: (“mental health” OR “behavioral health” AND “internalizing” OR “externalizing”); anxiety: (“anxiety” OR “obsessive-compulsive disorder” OR “panic” OR “worry” OR “generalized anxiety disorder” OR “stress” OR “phobia”); depression: (“depress*” OR “disruptive mood dysregulation disorder”); disruptive behavior disorders: (“conduct disorder” OR “oppositional defiant disorder” OR “attention-deficit” OR “disruptive behavior”); traumatic stress: (“traum*” OR “traum* exposure” OR “post-traumatic stress” OR “acute stress”); eating: (“eating disorder” OR “anorexia nervosa” OR “bulimia nervosa” OR “avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder” OR “binge eating” OR “picky eating”); suicide: (“suicide” OR “suicidality” OR “self-injurious”); bipolar: (“bipolar” OR “mania”); psychosis: (“schizophrenia” OR “psychosis” OR “psychotic”); substance use: “substance abuse” OR “substance use” OR “alcohol” OR “opioid” OR “tobacco” OR “nicotine” OR “marijuana” OR “cannabis”). We also conducted a hand-search for measures in three textbooks on youth EBA: Assessment of Childhood Disorders, Fourth Edition (Mash & Barkley, Citation2007), A Guide to Assessments that Work, Second Edition (Hunsley & Mash, Citation2018) and Diagnostic and Behavioral Assessment in Children and Adolescents: A Clinical Guide (McLeod, Jensen-Doss, & Ollendick, Citation2013).

This initial search returned 16,913 articles. Abstracts were screened for relevance by members of the authorship team (EBH, AT, BL, and RS). Articles were classified as “relevant” if they included a measure with a clearly defined youth sample (i.e., 18 or under) or were a review of measures for youth. Articles in this stage were excluded if they were clearly about diagnostic interviews, were not in English, or referenced a construct not of interest for this review (e.g., personality assessment). The team initially met and coded a subset of articles as a group (n = 20) and achieved perfect reliability. The remaining articles were therefore screened independently and the team met weekly to discuss any concerns and come to consensus when a coder was uncertain regarding the relevance of an abstract. A total of 1,920 articles were classified as relevant. These articles were subjected to full-text review in which the names of measures used in each article were extracted for the second phase of review; 663 measures were identified across the 1,920 articles included in this full-text review and were screened for eligibility inclusion criteria. The textbook search returned nine measures beyond the 663 obtained via literature search, for a total of 672 measures, lending support for the breadth of our search terms.

Measure Eligibility

Measures were required to meet four inclusion criteria to be eligible. Specifically, measures had to: (1) be brief (i.e., defined as 50 items or fewer, including sub-items), (2) be free (i.e., no associated cost for individual use), (3) be accessible (i.e., easily obtainable in ready-to-use format on the Internet), and (4) have available data for their psychometric properties for youth. To meet the “free” criterion, measures must have included a statement that the measure was available for individual use without charge. Measures did not have to be in the public domain to meet our criteria; thus, some identified measures are unalterable and may be subject to cost or institutional agreement if used by an organization. Of note, we excluded a subset of measures that met “brief” criteria that were freely available on the Internet in violation of copyright laws at the time of our search or could not be verified as freely available. To be considered “accessible,” the measure needed to be in a “ready-to-use” format (e.g., a list of measure items in a public-access journal article was not considered accessible, as it would require a clinician to reformat items in a separate document to add instructions and a rating scale).

Of the 672 measures initially identified, a subset of measures were excluded for length (n = 213), cost (n = 78), and poor accessibility (n = 284). Two additional measures were excluded because we were unable to find any published psychometric data in a youth sample. Our final sample constituted 95 measures.

Measure Psychometrics

Psychometric review was guided by criteria set forth by De Los Reyes and Langer (Citation2018). Given the number of measures identified, conducting a full psychometric review for each individual measure was not feasible. A subset of the identified measures has been subject to full systematic reviews of their psychometric properties (e.g., the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire; Kersten et al., Citation2016) or have publicly available instrument manuals. Whenever possible, we independently reviewed each measure’s psychometrics based on these existing reviews. When summative statements were not available (which was the norm), we examined psychometrics as reported both in the source manuscript for the measure and papers citing the source manuscript that focused on youth samples, using the “cited by” feature in Google Scholar (i.e., a “citation searching” approach to review; Wright, Golder, & Rodriguez-Lopez, Citation2014). Each measure was reviewed and classified as either having excellent, good, or adequate psychometric properties, consistent with the categories recommended by De Los Reyes and Langer (Citation2018).

Measures were classified as “excellent” if we were able to locate two or more separate psychometric studies that showed evidence of internal consistency > .9, test-retest > .7, some norms (e.g., M and SD for a large, relevant clinical sample), validity in at least two categories (e.g., convergent and discriminant), and treatment sensitivity (unless a screening measure). A measure could be classified as “good” in one of two ways: (1) if the measure met all of the psychometric properties outlined above under the “excellent” criteria, but we were only able to locate one study, or (2) if multiple studies demonstrated psychometric properties consistent with the criteria put forth by De Los Reyes and Langer for “good” measures (e.g., internal consistency values of .8–.9), evidence of at least one form of validity, minimal normative data, and at least some evidence for treatment sensitivity or test–retest reliability. We classified measures as “adequate” if the measure had some evidence of reliability or validity from one or more studies, but data were inconsistent (e.g., psychometric properties varied based on sample), limited (e.g., absence of normative data, no test–retest reliability data), or questionable (e.g., internal consistency values below .75). As we were unable to conduct a nuanced evaluation of validity, it is important to note that this adaptation of De Los Reyes and Langer’s criteria likely resulted in less conservative definitions of “excellent” and “good” psychometric strength, with measures more easily being categorized as excellent than if measures had been subjected to a full review. We also did not conduct reviews of measure inter-rater reliability, or repeatability. Twenty-two measures (23%) were randomly selected across the diagnostic categories for double coding and yielded excellent reliability (kappa = .79; Cicchetti, Citation1994).

Results

Supplemental Tables 1–10 display the following information for all identified measures: overall psychometric rating (i.e., excellent, good, or adequate), number of items, available forms (self, parent, clinician, or teacher report), intended age range for use, intended clinical use (screening, diagnostic aid/treatment planning, or progress monitoring), evidence of treatment sensitivity, and a link to the measure. We also denote which measures have freely available translations in other languages. illustrates an overview of all identified measures. A brief summary of the findings is below, by diagnostic category.

Overall Mental Health

Twelve of 90 identified measures of overall mental health met inclusion criteria (13%; Supplemental Table 1). Measures ranged from 6 to 48 items and covered youths age 1.5 to 18+ years old. In general, measures had strong psychometric properties, with four measures rated as having “excellent” psychometric support. Measures with excellent support included the Young Person’s Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation (Twigg et al., Citation2009), the Pediatric Symptom Checklist (Jellinek et al., Citation1988), the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (Goodman & Goodman, Citation2009), and the Ohio scales (Ogles, Melendez, Davis, & Lunnen, Citation2001). Three measures were rated as “good.” Five were rated as “adequate.”

Except for the Youth Top Problems Assessment (Weisz et al., Citation2011), all identified measures were standardized instruments assessing internalizing, externalizing, or general mental distress symptoms. Nine measures could be used for screening and/or aiding in diagnosis/treatment planning; eight were also intended for use with progress monitoring. Most measures had at least minimum evidence for internal consistency and construct validity; fewer had information about test–retest reliability, incremental validity, or treatment sensitivity. Five measures had support for their use for routine progress monitoring (at least monthly administration): the Ohio Youth Problems, Functioning, and Satisfaction Scales, the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire; the Symptoms and Functioning Severity Scale, the Behavior and Feelings Survey, and the Youth Top Problems; the latter three had support for their use on a weekly basis.

Anxiety

Eleven of 54 measures of anxiety met inclusion criteria for review (19%; Supplemental Table 2). Measures ranged from 7 to 47 items and provided coverage for youth ages 3 to 18+. Three measures were rated as having “excellent” psychometric properties and included the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (SCAS; Spence, Citation1998), the Screen for Child Anxiety-Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED; Birmaher et al., Citation1999), and the Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale (RCADS; Chorpita, Moffitt, & Gray, Citation2005). Five measures were rated as “good.” Three were rated as “adequate.”

All measures were designed to either screen for anxiety disorders and/or aid the diagnostic and treatment planning process with the exception of two, the PROMIS Anxiety (DeWalt et al., Citation2015) and the Short OCD Screener (Uher, Heyman, Mortimore, Frampton, & Goodman, Citation2007), which were designed specifically for screening in time-limited settings (e.g., primary care). Six measures were also intended for progress monitoring. Most measures rated as either “good” or “excellent” had support for their content, construct, and discriminant validity, but there was little information about the incremental validity of any measure. Only four measures had evidence of any treatment sensitivity: The Child Anxiety Life Interference Scale, RCADS, SCARED, and the SCAS. However, treatment sensitivity data were mixed and unclear as to the appropriate frequency with which these measures should be optimally administered for progress monitoring.

Depression

Thirteen of 68 measures of depressive (or mood) symptoms met inclusion criteria (19%; Supplemental Table 3). Measures ranged from 6 to 47 items and covered youth from the ages of 3 to 18+. Four measures met “excellent” criteria for psychometric properties: the Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (MFQ; Angold et al., Citation1995), the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; Johnson, Harris, Spitzer, & Williams, Citation2002), the Positive and Negative Affect Scale for Children (PANAS-C; Laurent et al., Citation1999), and the RCADS (Chorpita et al., Citation2005).Footnote1 Six measures were rated as “good.” Three were rated as “adequate.”

All measures were intended to be used for screening or aiding in diagnosis, with eight also intended for progress monitoring. All the measures rated as “good” or “excellent” had strong support for their reliability and validity and at least some evidence for their treatment sensitivity. However, treatment sensitivity data were primarily evidenced by pre- and post-treatment data in clinical trials; we identified little support for the use of any of the identified depression measures for routine progress monitoring with youth.

Disruptive Behavior

Twelve of 123 measures of disruptive behavior problems met inclusion criteria (10%; Supplemental Table 4). Measures ranged from 10 to 48 items and covered youth ages 2 to 18+. Four measures were classified as having “excellent” psychometric support: the IOWA Conners (Loney & Milich, Citation1982), the Strengths and Weaknesses of ADHD Symptoms and Normal-behavior scale (SWAN; Swanson et al., Citation2012), the Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham Rating Scale (SNAP-IV; Swanson et al., Citation2001), and the Vanderbilt ADHD Diagnostic Teacher Rating Scale (VADTRS; Wolraich et al., Citation2003). Four measures were rated as “good.” Four were rated as “adequate.”

The intended use of measures of disruptive behavior problems represented a range of screening, diagnostic aid, and progress monitoring tools. Some measures, such as the VADTRS, SNAP-IV, the Disruptive Behavior Disorders Rating Scale (DBDRS; Pelham, Gnagy, Greenslade, & Milich, Citation1992), and the Conduct Disorder Rating Scale (Waschbusch & Elgar, Citation2007) closely map on to DSM criteria and thus function as standalone diagnostic instruments for Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, Oppositional Defiant Disorder, or Conduct Disorder. Others are intended to assess disruptive or aggressive behavior more broadly to inform treatment planning and progress monitoring (e.g., the Inventory of Callous and Unemotional Traits; Essau, Sasagawa, & Frick, Citation2006). Although only five measures were intended for use as progress monitoring measures, eight had at least minimal evidence for their treatment sensitivity. Nearly all evidence for treatment sensitivity came from treatment trials where measures were administered pre- and post-treatment only. We identified little evidence for the use of any identified measures for routine progress monitoring with youth.

Traumatic Stress

Seven of 87 measures of traumatic stress met inclusion criteria (9%; Supplemental Table 5). Measures ranged from 8 to 36 items and covered youths age 2 to 18+. Only one measure met criteria for “excellent” psychometric support: the Child Post-Traumatic Cognitions Inventory (CPTCI; Meiser‐Stedman et al., Citation2009). Four measures were rated as “good.” Two were rated as “adequate.”

Overall, measures of traumatic-stress were primarily intended for use as screening tools or diagnostic aids. No measures were designed for progress monitoring, although five had at least some support for their treatment sensitivity as measured pre- and post-treatment: the CPTCI, the Child and Youth Resilience Measure Revised (CYRM; Jefferies et al., Citation2018), the Child and Adolescent Trauma Screen (CATS; Sachser et al., Citation2017), Child Stress Disorders Checklist (CSDC; Saxe et al., Citation2001), and Children’s Revised Impact of Event Scale (CRIES; Perrin, Meiser-Stedman, & Smith, Citation2005). Of note, three measures represented recent revisions or new measures, most likely in light of changed diagnostic criteria from DSM-IV to DSM-5. These measures (the CYRM, the CATS, and the Child PTSD Symptom Scale for DSM-5 [CPSS-5; Foa, Asnaani, Zang, Capaldi, & Yeh, Citation2018]) were classified as “good” solely because they had only one published study on their psychometric properties for the revised measure at the time of review, but may be classified as “excellent” as more studies with DSM-5 criteria are published.

Eating Disorders

Twelve of 77 measures of disordered eating met inclusion criteria (16%; Supplemental Table 6). Measures ranged from 6 to 40 items and were intended for use primarily with adolescents, although several had some psychometric data for their use with youth as young as 6 years old. Two measures, the Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale (EDDS; Stice, Telch, & Rizvi, Citation2000) and the Bulimic Investigatory Test (BITE; Henderson & Freeman, Citation1987) met criteria for excellent support. Four measures were rated as “good.” Six were rated as “adequate.”

All measures were intended for use as screening tools or diagnostic aids, with three also intended for progress monitoring. Most represented downward extensions of measures with ample psychometric support for their use with undergraduate or adult samples but either had limited psychometric data to support their use with youth or have demonstrated inconsistent or unstable factor structures when applied to adolescent samples. Five measures were shown to have at least minimal treatment sensitivity (i.e., evidence of change from “pre” to “post” treatment) in a youth or adolescent sample: the EDDS, the BITE, the Children’s Eating Attitudes Test (ChEAT; Maloney, McGuire, & Daniels, Citation1988), the Body Checking Questionnaire (BCQ; Reas, Whisenhunt, Netemeyer, & Williamson, Citation2002), and the Ideal Body Stereotype Scale-Revised (IBSS-R; Stice, Citation2001). Only the BITE had support for its use beyond pre- and post-treatment and can be used on a monthly basis.

Suicidality

Six of 73 measures of suicidality met inclusion criteria (8%; Supplemental Table 7). Measures ranged from 4 to 40 items and covered youths aged 5 and up, although most measures were designed for use with adolescents only. Only one measure was classified as “excellent” with respect to its psychometrics: the Alexian Brothers Urge to Self-Injure Scale (ABUSI; Washburn, Juzwin, Styer, & Aldridge, Citation2010). One measure was rated as “good.” Four were rated as “adequate.”

Identified measures of suicidality were designed for screening and/or risk assessment, with the exceptions of the ABUSI and the Functional Assessment of Self-Mutilation (Lloyd-Lloyd-Richardson, Perrine, Dierker, & Kelley, Citation2007), which were designed primarily to inform treatment or safety planning. With the exceptions of the Columbia Suicide Screen Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS; Posner et al., Citation2008), which was classified as having “good” support for its use with youth, and the ABUSI, identified measures had limited or inconsistent published psychometric data to support their use. Only the ABUSI and C-SSRS had any data to support their treatment sensitivity; the ABUSI has support for its use pre- and post-treatment only, while the C-SSRS has demonstrated sensitivity to change over a six-week period. No measure had support for its use as a routine progress monitoring tool.

Bipolar/Mania

Six of 11 measures of bipolar or manic symptoms met inclusion criteria (55%; Supplemental Table 8). Measures ranged from 10 to 21 items and were intended for youths aged 5 to 18 +. Only one measure, the Child Mania Rating Scale-Parent Version (CMRS-P; Pavuluri, Henry, Devineni, Carbray, & Birmaher, Citation2006), met criteria for excellent psychometric properties. Four measures were rated as “good.” One was rated as “adequate.”

All identified measures were intended as screening tools or diagnostic aids; two were also intended for use with progress monitoring. Overall, measures had adequate support for their internal consistency, convergent, and discriminant validity, although evidence for test–retest reliability and treatment sensitivity were more limited. The CMRS-P and YMRS were the only identified measures with evidence for treatment sensitivity. The CMRS-P can be administered weekly for progress monitoring.

Psychosis

Three of 39 measures of psychosis met inclusion criteria (8%; Supplemental Table 9). Measures ranged from 21 to 42 items. All three measures were intended for adolescents aged 12 and up and were designed to be used primarily for screening. No measure was rated as having “excellent” psychometric properties. Only one measure was classified as “good” with respect to psychometric properties, the Prodromal Questionnaire Brief (Loewy, Pearson, Vinogradov, Bearden, & Cannon, Citation2011), which showed good internal consistency and concurrent and predictive validity but lacked data on test–retest reliability and treatment sensitivity. Two measures were classified as “adequate.” There was no evidence for test–retest reliability or treatment sensitivity for any identified measure to support its use as a progress monitoring tool with youth.

Substance Use

Thirteen of 50 measures of substance use/abuse met inclusion criteria (26%; Supplemental Table 10). Measures ranged from 4 to 35 items and were intended for individuals ages 12 and up. Only one measure, the Hooked on Nicotine Checklist (HONC; DiFranza et al., Citation2002) met criteria for “excellent” psychometric properties. Four measures were rated as “good.” Eight were rated as “adequate.”

All measures were intended as screening tools or to support the diagnostic process; two were also intended for use with progress monitoring. Identified substance use measures varied as to whether they represented broad or specific measures of substance use. Six measures were designed to measure substance use broadly, three specifically assessed nicotine addiction, three assessed cannabis use/abuse, and one measure focused on alcohol. Seven measures were designed as screening tools only and represented downward extensions of measures developed with undergraduate or adult samples and had limited psychometric data for their use with adolescent samples. Only two measures had marginal support for their treatment sensitivity (pre-treatment to 6 months later): the HONC and the Cannabis Use Problems Identification Test (CUPIT; Bashford, Flett, & Copeland, Citation2010). No measure had any psychometric evidence for its utility as a routine progress monitoring tool with youth.

Discussion

This systematic review offers the most comprehensive information available on the psychometric properties of brief, free, and accessible clinical measures for youth mental health. The measures described represent the current state of the science for pragmatic EBA measures and can also serve as an expanded reference to inform selection and use of EBA measures in routine and low-resource clinical settings. Our review identified over 600 measures of youth mental health symptoms, yet relatively few (14%, n = 95) were pragmatic tools that may be easily implemented in the community. We identified nearly five times the number of brief, free, accessible, and validated measures than the initial review conducted by Beidas et al. (Citation2015). Existing measures generally covered a wide age range (2 to 18+) and, with the exception of psychosis measures, all diagnostic areas had at least one measure classified as having excellent psychometric support. However, only a small subset of available measures (3%, n = 21) were classified as having “excellent” psychometric properties – even with less conservative evaluative criteria than those delineated by De Los Reyes and Langer (Citation2018). There were notable gaps in the availability of brief, free, accessible, and validated youth measures for disordered eating, suicide, psychosis, and substance use. Furthermore, even among measures with relatively strong reliability and validity data that we classified as having excellent psychometric properties, treatment sensitivity data were limited; only seven measures (1%) across all of the examined diagnostic categories had treatment sensitivity data to support monthly administration for routine progress monitoring. As more frequent administration of measures may be needed to inform clinical decision-making with respect to treatment sequencing and personalization, this suggests a major weakness in the current literature.

Taken together, results suggest more work is needed to advance the science of pragmatic measures to be used in EBA for youth mental health. Future research should focus on developing pragmatic measures that can be used to monitor treatment progress and evaluating their psychometric properties in the settings where youth are most likely to receive treatment (e.g., community mental health clinics, schools, primary care offices). Below, we delineate several important next steps to achieve this aim and to increase the likelihood that EBA will be implemented in diverse community settings.

Measure Development

Our review highlights several key areas for measure development. First, there is a dearth of well-validated measures in key areas of public health concern in youth: disordered eating, suicidality, psychosis, and substance use. There is an urgent need to develop new measures or improve existing measures to adequately assess these areas. Measures should be developed specifically for youth and adolescent needs, rather than as downward extensions of adult measures. As can be seen in Supplemental Tables 6, 7, 9, and 10, many of the identified measures in these areas rely primarily on youth self-report. Thus, new measures should be designed to be completed by multiple informants (e.g., youth and caregivers). Second, only one of our 95 identified measures was an idiographic, or individualized, assessment measure (the Youth Top Problems; Weisz et al., Citation2011). There is evidence that practicing clinicians view idiographic assessment tools more positively and use them more often than standardized assessment tools (Jensen-Doss, Becker-Haimes, et al., Citation2018). Thus, future measure development should focus on developing pragmatic, individualized assessment measures that can be used to support the delivery of evidence-based treatments. Third, to enhance the likelihood that measures will be readily implemented in community settings, we recommend that future research consider a community-partnered approach to measure development. Involving practicing clinicians and other stakeholders (e.g., agency leaders, clients) in the design and evaluation of new youth measures could ensure that the measure will be viewed as acceptable, feasible, and clinically informative for use in community settings.

Treatment Sensitivity and Clinical Utility in Measure Development

Our review indicates there is a need for greater attention to evaluating the treatment sensitivity of measures to inform their use in routine progress monitoring in future research. This could be done in several ways and begs the question of whether new measures should be developed to specifically monitor treatment progress or whether existing freely available measures should be further studied. One possible low-cost way to examine the utility of current measures for progress monitoring is to mine existing clinical trials datasets that administered many assessment measures at frequent time points over the course of youth treatment (e.g., Walkup et al., Citation2008). As noted above, development and evaluation of new measures to monitor treatment progress would ideally be done in collaboration with key stakeholders in community settings.

Evaluate Psychometric Properties of Measures in Community Settings

Research is needed that explicitly focuses on the performance of youth measures in routine clinical settings. Just as evidence-based treatments often show reduced effect sizes when delivered in the community (Weisz, Ng, & Bearman, Citation2014), measures may not perform comparably psychometrically when applied to youth presenting in settings such as community mental health or primary care (Youngstrom, Meyers, Youngstrom, Calabrese, & Findling, Citation2006). Future meta-analytic work examining psychometric performance of brief measures might also consider coding for the setting and population features to test whether setting characteristics moderate psychometric performance.

Comparative trials of the psychometric properties of established youth measures within problem areas in these settings are also needed to inform EBA implementation efforts. Currently, there is little empirical data to guide decision-making for the use of one measure over another. Comparative trials examining the utility of specific batteries of pragmatic measures across multiple problem areas are also needed. In particular, it would be useful for future studies to test the reliability, validity, and utility of a collection of brief screeners or diagnostic aids. Such a battery could then be tested relative to gold-standard diagnostic interviews to determine whether the lengthier and often more costly interviews provide incremental utility over a carefully curated set of pragmatic questionnaires. This could shed light on how to best implement EBA in community settings given time and resource constraints.

Develop Criteria for Assessing Measures for EBA Implementation Readiness

An important next step in evaluating pragmatic measures to be used in EBA is to add dimensions related to their acceptability and feasibility of implementation. As noted above, clinicians report varying levels of acceptability for different measures (e.g., standardized vs. individualized assessment; Jensen-Doss, Becker-Haimes, et al., Citation2018). A measure’s brevity does not indicate that it is easy to administer, score, and interpret. For example, some measures (e.g., the RCADS) provide freely available tools to assist clinicians with scoring and interpretation, but many do not. Future research should examine the acceptability and feasibility of measures from the perspectives of key stakeholders such as consumers, clinicians, and organizational leadership. Such work could help select specific measures most likely to have buy-in and be sustainably implemented.

It is worth noting that, through the course of our review, we identified the existence of multiple repositories designed to house measures (See Supplementary Materials 2 for an overview of identified repositories) as well as several additional repositories that are under development. The growth of these repositories likely contributed to our identification of a significantly greater number of freely available measures than the initial review conducted by Beidas et al. (Citation2015). However, the measures contained in each repository often did not overlap and were not always updated with the latest versions of the measure. Repositories varied in how they selected measures to include; some required authors to self-submit and self-report on the measure’s psychometric evidence, others gathered experts to recommend measures for inclusion. The dynamic nature of these repositories suggests that the landscape of freely available measures may shift quickly; however, in the absence of a single, coordinated effort to house pragmatic measures, these repositories are unlikely to keep pace with advancing science.

Results should be taken in the context of limitations. First, while we tried to be as comprehensive as possible in our review, it is possible additional measures exist that were not identified through our literature search. Future reviews might expand search methods to include screening published practice parameters for assessment and meta-analyses of published measures (e.g., by crossing the disorder-specific search terms with “AND meta-analysis”). Most notably, we did not conduct a formal systematic review of the psychometric properties for each of the measures within each of the De Los Reyes and Langer (Citation2018) categories and instead employed a “citation searching” approach to review. Thus, it is possible that some of our measures had additional psychometric support beyond what is reported here; this may be particularly true for measures that have multiple “primary source” citations. As previously noted, our adapted evaluation criteria likely resulted in an overestimation of the strength of the psychometric support for certain measures. However, given the relatively few measures identified as having excellent psychometric properties, we do not feel a more conservative application of psychometric review criteria would have substantially changed our recommendations for future research. Related, we note that the De Los Reyes and Langer (Citation2018) criterion for internal consistency values may be in conflict with our focus on brief measures, as typical interpretation of Cronbach’s alpha values may not be the appropriate approach for very short scales (Streiner & Kottner, Citation2014). Future reviews should consider alternative review criteria for ultra-brief measures, such as average inter-item values or use of a “sliding scale” for alpha values commensurate with scale length (e.g., .90 remains the criterion for “excellent” support for items with 20 or more items, but lower values are used to establish “excellent” support for shorter scales) and reducing the weight placed on alpha values for measure classifications (Youngstrom, Salcedo, Frazier, & Perez Algorta, Citation2019).

We also focused our review primarily on symptoms for a range of presenting youth mental health concerns; other measures may of interest to community clinicians (e.g., functioning, quality of life) or of clinical use with respect to progress monitoring to track target mechanisms of treatment (e.g., emotion regulation, social skills, family accommodation, parenting practices, intolerance of uncertainty), particularly as the field’s understanding of key treatment mechanisms continues to develop (McKay, Citation2019). These constructs may be targeted in future reviews. Given the number of measures identified, and the vast and complex literature regarding informant agreement for youth (De Los Reyes et al., Citation2015), we also did not conduct a review of measure interrater reliability (i.e., correlations between parent, youth, and teacher report). However, as emerging evidence suggests informant disagreement can be used to inform monitoring of treatment progress (Becker-Haimes, Jensen-Doss, Birmaher, Kendall, & Ginsburg, Citation2018; Goolsby et al., Citation2018), a future review may focus specifically on informant agreement for brief, free, and accessible measures. Finally, an additional challenge that emerged in our review concerned how to review measures that represented revisions to reflect new diagnostic criteria (e.g., the CPSS updated to reflect DSM-5 criteria). In the absence of established criteria, we elected to review the properties of the revised measure as its own entity. Future work should establish clear criteria for evaluating revised measures in which there is substantial psychometric evaluation of the original measure.

This review also has notable strengths. We employed a rigorous review process to identify and evaluate a broad range of youth measures to be used in EBA; many measures have been evaluated in so many studies as to warrant possible Evidence Base Updates on their own. Our emphasis on examining the treatment sensitivity of EBA measures fills a critical gap in current evidence-based assessment reviews, particularly with increased moves to implement EBA in routine community settings and increasing efforts across the field to tie payment to outcomes and quality metrics (such as in value-based purchasing; Kilbourne et al., Citation2018) and highlights the need for more work developing free, brief, and accessible measures with adequate treatment sensitivity for use in progress monitoring in community settings.

Conclusions

There is much to be done with respect to the development, evaluation, and implementation of measures for youth mental health to be used in EBA efforts. Our review identified measures that can be freely used by community clinicians. However, there are limited options for clinicians when it comes to selecting measures to monitor treatment progress. More research is needed to expand upon existing measures and improve our understanding of the feasibility of implementing these measures in diverse clinical contexts.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (79.4 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The RCADS measure was identified in both our search for measures of anxiety and measures of depression. As such, it is counted separately for each category in our review, despite being the same measure.

References

- Adamson, S. J., & Sellman, J. D. (2003). A prototype screening instrument for cannabis use disorder: The Cannabis Use Disorders Identification Test (CUDIT) in an alcohol-dependent clinical sample. Drug and Alcohol Review, 22(3), 309–315. doi:10.1080/0959523031000154454

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: Author.

- Angold, A., Costello, E. J., Messer, S. C., Pickles, A., Winder, F., & Silver, D. (1995). The development of a short questionnaire for use in epidemiological studies of depression in children and adolescents. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 5, 1–12.

- Athay, M. M., Riemer, M., & Bickman, L. (2012). The Symptoms and Functioning Severity Scale (SFSS): Psychometric evaluation and discrepancies among youth, caregiver, and clinician ratings over time. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 39(1–2), 13–29. doi:10.1007/s10488-012-0403-2

- Bashford, J., Flett, R., & Copeland, J. (2010). The Cannabis Use Problems Identification Test (CUPIT): Development, reliability, concurrent and predictive validity among adolescents and adults. Addiction, 105(4), 615–625. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02859.x

- Bearman, S. K., & Weisz, J. R. (2015). Comprehensive treatments for youth comorbidity–Evidence‐guided approaches to a complicated problem. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 20(3), 131–141. doi:10.1111/camh.12092

- Becker-Haimes, E. M., Jensen-Doss, A., Birmaher, B., Kendall, P. C., & Ginsburg, G. S. (2018). Parent–Youth informant disagreement: Implications for youth anxiety treatment. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 23(1), 42–56. doi:10.1177/1359104516689586

- Beidas, R. S., Stewart, R. E., Walsh, L., Lucas, S., Downey, M. M., Jackson, K., … Mandell, D. S. (2015). Free, brief, and validated: Standardized instruments for low-resource mental health settings. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 22(1), 5–19. doi:10.1016/j.cbpra.2014.02.002

- Beusenberg, M., & Orley, J. H., & World Health Organization. (1994). A user’s guide to the self reporting questionnaire (SRQ (No. WHO/MNH/PSF/94.8. Unpublished). Geneva: Author. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/61113

- Bickman, L., Douglas, S. R., De Andrade, A. R. V., Tomlinson, M., Gleacher, A., Olin, S., & Hoagwood, K. (2016). Implementing a measurement feedback system: A tale of two sites. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43(3), 410–425. doi:10.1007/s10488-015-0647-8

- Bickman, L., Kelley, S. D., Breda, C., de Andrade, A. R., & Riemer, M. (2011). Effects of routine feedback to clinicians on mental health outcomes of youths: Results of a randomized trial. Psychiatric Services, 62(12), 1423–1429. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.002052011

- Birelson, P. (1981). The validity of depressive disorder in childhood and development of a self-rating scale: A research report. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 22, 73–88. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.1981.tb00533.x

- Birmaher, B., Brent, D. A., Chiappetta, L., Bridge, J., Monga, S., & Baugher, M. (1999). Psychometric properties of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): A replication study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 38(10), 1230–1236. doi:10.1097/00004583-199910000-00011

- Bland, J. M., & Altman, D. (1986). Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. The Lancet, 327(8476), 307–310. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(86)90837-8

- Bohn, K., Doll, H. A., Cooper, Z., O’Connor, M., Palmer, R. L., & Fairburn, C. G. (2008). The measurement of impairment due to eating disorder psychopathology. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46(10), 1105–1110. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2008.06.012

- Boswell, J. F., Kraus, D. R., Miller, S. D., & Lambert, M. J. (2015). Implementing routine outcome monitoring in clinical practice: Benefits, challenges, and solutions. Psychotherapy Research, 25(1), 6–19. doi:10.1080/10503307.2013.817696

- Brooks, S. J., Krulewicz, S. P., & Kutcher, S. (2003). The Kutcher adolescent depression scale: Assessment of its evaluative properties over the course of an 8-week pediatric pharmacotherapy trial. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 13(3), 337–349. doi:10.1089/104454603322572679

- Brown, R. L., & Rounds, L. A. (1995). Conjoint screening questionnaires for alcohol and other drug abuse: Criterion validity in a primary care practice. Wisconsin Medical Journal, 94(3), 135–140.

- Bush, G., Fink, M., Petrides, G., Dowling, F., & Francis, A. (1996). Catatonia. I. Rating scale and standardized examination. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 93(2), 129–136. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb09814.x

- Chorpita, B. F., Moffitt, C. E., & Gray, J. (2005). Psychometric properties of the revised child anxiety and depression scale in a clinical sample. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 43(3), 309–322. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2004.02.004

- Chorpita, B. F., Tracey, S. A., Brown, T. A., Collica, T. J., & Barlow, D. H. (1997). Assessment of worry in children and adolescents: An adaptation of the Penn State worry questionnaire. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 35(6), 569–581. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(96)00116-7

- Cicchetti, D. V. (1994). Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychological Assessment, 6, 284–290. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.6.4.284

- Connor‐Smith, J. K., & Weisz, J. R. (2003). Applying treatment outcome research in clinical practice: Techniques for adapting interventions to the real world. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 8(1), 3–10. doi:10.1111/1475-3588.00038

- Cooper, P. J., Taylor, M. J., Cooper, Z., & Fairburn, C. G. (1987). The development and validation of the body shape questionnaire. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 6(4), 485–494. doi:10.1002/1098-108X(198707)6:4<485::AID-EAT2260060405>3.0.CO;2-O

- Couwenbergh, C., Van Der Gaag, R. J., Koeter, M., De Ruiter, C., & Van den Brink, W. (2009). Screening for substance abuse among adolescents validity of the CAGE-AID in youth mental health care. Substance Use & Misuse, 44(6), 823–834. doi:10.1080/10826080802484264

- De Los Reyes, A., Augenstein, T. M., Wang, M., Thomas, S. A., Drabick, D. A., Burgers, D. E., & Rabinowitz, J. (2015). The validity of the multi-informant approach to assessing child and adolescent mental health. Psychological Bulletin, 141(4), 858. doi:10.1037/a0038498

- De Los Reyes, A., & Langer, D. A. (2018). Assessment and the journal of clinical child and adolescent psychology’s evidence base updates series: Evaluating the tools for gathering evidence. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 47(3), 357–365. doi:10.1080/15374416.2018.1458314

- Degenhardt, L., Stockings, E., Patton, G., Hall, W. D., & Lynskey, M. (2016). The increasing global health priority of substance use in young people. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(3), 251–264. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00508-8

- DeWalt, D. A., Gross, H. E., Gipson, D. S., Selewski, D. T., DeWitt, E. M., Dampier, C. D., … Varni, J. W. (2015). PROMIS® pediatric self-report scales distinguish subgroups of children within and across six common pediatric chronic health conditions. Quality of Life Research, 24(9), 2195–2208. doi:10.1007/s11136-015-0953-3

- DiFranza, J. R., Savageau, J. A., Fletcher, K., Ockene, J. K., Rigotti, N. A., McNeill, A. D., … Wood, C. (2002). Measuring the loss of autonomy over nicotine use in adolescents: The DANDY (Development and Assessment of Nicotine Dependence in Youths) study. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 156(4), 397–403. doi:10.1001/archpedi.156.4.397

- Edwards, S. L., Rapee, R. M., Kennedy, S. J., & Spence, S. H. (2010). The assessment of anxiety symptoms in preschool-aged children: The revised Preschool Anxiety Scale. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 39(3), 400–409. doi:10.1080/15374411003691701

- Eisen, S. V., Dickey, B., & Sederer, L. I. (2000). A self-report symptom and problem rating scale to increase inpatients’ involvement in treatment. Psychiatric Services, 51(3), 349–353. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.51.3.349

- Essau, C. A., Sasagawa, S., & Frick, P. J. (2006). Callous-unemotional traits in a community sample of adolescents. Assessment, 13(4), 454–469. doi:10.1177/1073191106287354

- Fabiano, G. A., Pelham., W. E., Jr., Waschbusch, D. A., Gnagy, E. M., Lahey, B. B., Chronis, A. M., … Burrows-MacLean, L. (2006). A practical measure of impairment: Psychometric properties of the impairment rating scale in samples of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and two school-based samples. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 35(3), 369–385. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp3503_3

- Farmer, C. A., & Aman, M. G. (2009). Development of the children’s scale of hostility and aggression: Reactive/proactive (C-SHARP). Research in Developmental Disabilities, 30(6), 1155–1167. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2009.03.001

- Faulstich, M. E., Carey, M. P., Ruggiero, L., Enyart, P., & Gresham, F. (1986). Assessment of depression in childhood and adolescence: An evaluation of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Children (CES-DC). American Journal of Psychiatry, 143(8), 1024–1027. doi:10.1176/ajp.143.8.1024

- Foa, E. B., Asnaani, A., Zang, Y., Capaldi, S., & Yeh, R. (2018). Psychometrics of the child PTSD symptom scale for DSM-5 for trauma-exposed children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 47(1), 38–46. doi:10.1080/15374416.2017.1350962

- Garner, D. M., Olmsted, M. P., Bohr, Y., & Garfinkel, P. E. (1982). The eating attitudes test: Psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psychological Medicine, 12(4), 871–878. doi:10.1017/S0033291700049163

- Gearhardt, A. N., Roberto, C. A., Seamans, M. J., Corbin, W. R., & Brownell, K. D. (2013). Preliminary validation of the Yale food addiction scale for children. Eating Behaviors, 14(4), 508–512. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.07.002

- Gleason, M. M., Dickstein, S., & Zeanah, C. H. (2006). Further validation of the early childhood screening assessment. Presented at the 53rd Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry National Meeting, San Diego, CA.

- Goodman, A., & Goodman, R. (2009). Strengths and difficulties questionnaire as a dimensional measure of child mental health. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 48(4), 400–403. doi:10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181985068

- Goolsby, J., Rich, B. A., Hinnant, B., Habayeb, S., Berghorst, L., De Los Reyes, A., & Alvord, M. K. (2018). Parent–Child informant discrepancy is associated with poorer treatment outcome. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(4), 1228–1241. doi:10.1007/s10826-017-0946-7

- Gossop, M., Darke, S., Griffiths, P., Hando, J., Powis, B., Hall, W., & Strang, J. (1995). The Severity of Dependence Scale (SDS): Psychometric properties of the SDS in English and Australian samples of heroin, cocaine and amphetamine users. Addiction, 90(5), 607–614. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.1995.tb02199.x

- Green, J. G., Gruber, M. J., Sampson, N. A., Zaslavsky, A. M., & Kessler, R. C. (2010). Improving the K6 short scale to predict serious emotional disturbance in adolescents in the USA. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 19(S1), 23–35. doi:10.1002/mpr.314

- Hamilton, M. A. X. (1959). The assessment of anxiety states by rating. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 32(1), 50–55. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8341.1959.tb00467.x

- Heatherton, T. F., Kozlowski, L. T., Frecker, R. C., & Fagerstrom, K. O. (1991). The Fagerström test for nicotine dependence: A revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction, 86(9), 1119–1127. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x

- Henderson, M., & Freeman, C. P. L. (1987). A self-rating scale for bulimia: The ‘BITE’. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 150(1), 18–24. doi:10.1192/bjp.150.1.18

- Henry, J. D., & Crawford, J. R. (2005). The 21-item version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS–21): Normative data and psychometric evaluation in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44(22), 227–239. doi:10.1348/014466505X29657

- Horowitz, L. M., Bridge, J. A., Teach, S. J., Ballard, E., Klima, J., Rosenstein, D. L., … Joshi, P. (2012). Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ): A brief instrument for the pediatric emergency department. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 166(12), 1170–1176. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2012.1276

- Hunsley, J., & Mash, E. J. (2008). Developing criteria for evidence-based assessment: An introduction to assessments that work. In J. Hunsley & E. J. Mash (Eds.), A guide to assessments that work (pp. 3–14). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Hunsley, J., & Mash, E. J. (2018). A guide to assessments that work (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Jefferies, P., McGarrigle, L., & Ungar, M. (2018). The CYRM-R: A Rasch-validated revision of the child and youth resilience measure. Journal of Evidence-Informed Social Work, 16(1), 70–92. doi:10.1080/23761407.2018.1548403

- Jellinek, M. S., Murphy, J. M., Robinson, J., Feins, A., Lamb, S., & Fenton, T. (1988). Pediatric symptom checklist: Screening school-age children for psychosocial dysfunction. The Journal of Pediatrics, 112(2), 201–209. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(88)80056-8

- Jensen-Doss, A. (2015). Practical, evidence-based clinical decision making: Introduction to the special series. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 22(1), 1–4. doi:10.1016/j.cbpra.2014.08.001

- Jensen‐Doss, A. (2011). Practice involves more than treatment: How can evidence‐based assessment catch up to evidence‐based treatment? Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 18(2), 173–177. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2850.2011.01248.x

- Jensen-Doss, A., Becker-Haimes, E. M., Smith, A. M., Lyon, A. R., Lewis, C. C., Stanick, C. F., & Hawley, K. M. (2018). Monitoring treatment progress and providing feedback is viewed favorably but rarely used in practice. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 45(1), 48–61. doi:10.1007/s10488-016-0763-0

- Jensen-Doss, A., Ehrenreich-May, J., Nanda, M. M., Maxwell, C. A., LoCurto, J., Shaw, A. M., … Ginsburg, G. S. (2018). Community Study of Outcome Monitoring for Emotional Disorders in Teens (COMET): A comparative effectiveness trial of a transdiagnostic treatment and a measurement feedback system. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 74, 18–24. doi:10.1016/j.cct.2018.09.011

- Jensen-Doss, A., & Hawley, K. M. (2010). Understanding barriers to evidence-based assessment: Clinician attitudes toward standardized assessment tools. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 39(6), 885–896. doi:10.1080/15374416.2010.517169

- Jensen-Doss, A., Smith, A. M., Becker-Haimes, E. M., Ringle, V. M., Walsh, L. M., Nanda, M., … Lyon, A. R. (2018). Individualized progress measures are more acceptable to clinicians than standardized measures: Results of a national survey. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 45(3), 392–403. doi:10.1007/s10488-017-0833-y

- Jensen-Doss, A., & Weisz, J. R. (2008). Diagnostic agreement predicts treatment process and outcomes in youth mental health clinics. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(5), 711–722. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.76.5.711

- Johnson, J. G., Harris, E. S., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2002). The patient health questionnaire for adolescents: Validation of an instrument for the assessment of mental disorders among adolescent primary care patients. Journal of Adolescent Health, 30(3), 196–204. doi:10.1016/S1054-139X(01)00333-0

- Joiner, T. E., Jr., Pfaff, J. J., & Acres, J. G. (2002). A brief screening tool for suicidal symptoms in adolescents and young adults in general health settings: Reliability and validity data from the Australian National general practice youth suicide prevention project. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 40(4), 471–481. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(01)00017-1

- Kaufman, J., Birmaher, B., Brent, D., Rao, U. M. A., Flynn, C., Moreci, P., … Ryan, N. (1997). Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(7), 980–988. doi:10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021

- Kazdin, A. E., Rodgers, A., & Colbus, D. (1986). The hopelessness scale for children: Psychometric characteristics and concurrent validity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 54(2), 241–245. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.54.2.241

- Kelly, S. M., Gryczynski, J., Mitchell, S. G., Kirk, A., O’Grady, K. E., & Schwartz, R. P. (2014). Validity of brief screening instrument for adolescent tobacco, alcohol, and drug use. Pediatrics, 133(5), 819–826. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-2346

- Kenardy, J. A., Spence, S. H., & Macleod, A. C. (2006). Screening for posttraumatic stress disorder in children after accidental injury. Pediatrics, 118(3), 1002–1009. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-0406

- Kersten, P., Czuba, K., McPherson, K., Dudley, M., Elder, H., Tauroa, R., & Vandal, A. (2016). A systematic review of evidence for the psychometric properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 40(1), 64–75. doi: 10.1177%2F0165025415570647

- Keyes, C. L. (2006). The subjective well-being of America’s youth: Toward a comprehensive assessment. Adolescent & Family Health, 4(1), 3–11.

- Kilbourne, A. M., Beck, K., Spaeth-Rublee, B., Ramanuj, P., O’Brien, R. W., Tomoyasu, N., & Pincus, H. A. (2018). Measuring and improving the quality of mental health care: A global perspective. World Psychiatry, 17(1), 30–38. doi:10.1002/wps.20482

- Klein, J. B., Lavigne, J. V., & Seshadri, R. (2010). Clinician‐assigned and parent‐report questionnaire‐derived child psychiatric diagnoses: Correlates and consequences of disagreement. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 80(3), 375–385. doi:10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01041.x

- Knight, D. K., Becan, J. E., Landrum, B., Joe, G. W., & Flynn, P. M. (2014). Screening and assessment tools for measuring adolescent client needs and functioning in substance abuse treatment. Substance Use & Misuse, 49(7), 902–918. doi:10.3109/10826084.2014.891617

- Kotte, A., Hill, K. A., Mah, A. C., Korathu-Larson, P. A., Au, J. R., Izmirian, S., … Higa-McMillan, C. K. (2016). Facilitators and barriers of implementing a measurement feedback system in public youth mental health. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43(6), 861–878. doi:10.1007/s10488-016-0729-2

- Kronenberger, W. G., Giauque, A. L., & Dunn, D. W. (2007). Development and validation of the outburst monitoring scale for children and adolescents. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 17(4), 511–526. doi:10.1089/cap.2007.0094

- Kurz, S., Van Dyck, Z., Dremmel, D., Munsch, S., & Hilbert, A. (2015). Early-onset restrictive eating disturbances in primary school boys and girls. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 24(7), 779–785. doi:10.1007/s00787-014-0622-z

- Lambert, M. (2007). Presidential address: What we have learned from a decade of research aimed at improving psychotherapy outcome in routine care. Psychotherapy Research, 17, 1–14. doi:10.1080/10503300601032506

- Lambert, M. J., Whipple, J. L., Hawkins, E. J., Vermeersch, D. A., Nielsen, S. L., & Smart, D. W. (2003). Is it time for clinicians to routinely track patient outcome? A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10, 288–301. doi:10.1093/clipsy.bpg025

- Laurent, J., Catanzaro, S. J., Joiner, T. E., Jr., Rudolph, K. D., Potter, K. I., Lambert, S., … Gathright, T. (1999). A measure of positive and negative affect for children: Scale development and preliminary validation. Psychological Assessment, 11(3), 326. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.11.3.326

- Levy, S., Weiss, R., Sherritt, L., Ziemnik, R., Spalding, A., Van Hook, S., & Shrier, L. A. (2014). An electronic screen for triaging adolescent substance use by risk levels. JAMA Pediatrics, 168(9), 822–828. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.774

- Lloyd-Richardson, E. E., Perrine, N., Dierker, L., & Kelley, M. L. (2007). Characteristics and functions of non-suicidal self-injury in a community sample of adolescents. Psychological Medicine, 37(8), 1183–1192. doi:10.1017/S003329170700027X

- Loewy, R. L., Pearson, R., Vinogradov, S., Bearden, C. E., & Cannon, T. D. (2011). Psychosis risk screening with the Prodromal Questionnaire—Brief version (PQ-B). Schizophrenia Research, 129(1), 42–46. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2011.03.029

- Loflin, M., Babson, K., Browne, K., & Bonn-Miller, M. (2018). Assessment of the validity of the CUDIT-R in a subpopulation of cannabis users. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 44(1), 19–23. doi:10.1080/00952990.2017.1376677

- Loney, J. P., & Milich, R. (1982). Hyperactivity, inattention, and aggression in clinical practice. In M. Wolraich & D. K. Routh (Eds.), Advances in developmental and behavioral pediatrics (2nd ed., pp. 113–147). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

- Luby, J. L., Heffelfinger, A., Koenig-McNaught, A. L., Brown, K., & Spitznagel, E. (2004). The preschool feelings checklist: A brief and sensitive screening measure for depression in young children. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 43(6), 708–717. doi:10.1097/01.chi.0000121066.29744.08

- Lyneham, H. J., Abbott, M. J., & Rapee, R. M. (2007). Interrater reliability of the anxiety disorders interview schedule for DSM-IV: Child and parent version. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 46(6), 731–736. doi:10.1097/chi.0b013e3180465a09

- Lyneham, H. J., Sburlati, E. S., Abbott, M. J., Rapee, R. M., Hudson, J. L., Tolin, D. F., & Carlson, S. E. (2013). Psychometric properties of the Child Anxiety Life Interference Scale (CALIS). Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 27(7), 711–719. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.09.008

- Lyneham, H. J., Street, A. K., Abbott, M. J., & Rapee, R. M. (2008). Psychometric properties of the school anxiety scale—Teacher report (SAS-TR). Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 22(2), 292–300. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.02.001

- Lyon, A. R., Dorsey, S., Pullmann, M., Silbaugh-Cowdin, J., & Berliner, L. (2015). Clinician use of standardized assessments following a common elements psychotherapy training and consultation program. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 42(1), 47–60. doi:10.1007/s10488-014-0543-7

- Lyon, A. R., Lewis, C. C., Boyd, M. R., Hendrix, E., & Liu, F. (2016). Capabilities and characteristics of digital measurement feedback systems: Results from a comprehensive review. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43(3), 441–466. doi:10.1007/s10488-016-0719-4

- Lyon, A. R., Pullmann, M. D., Whitaker, K., Ludwig, K., Wasse, J. K., & McCauley, E. (2019). A digital feedback system to support implementation of measurement-based care by school-based mental health clinicians. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 48(sup1), S168–S179. doi:10.1080/15374416.2017.1280808

- Maloney, M. J., McGuire, J. B., & Daniels, S. R. (1988). Reliability testing of a children’s version of the eating attitude test. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 27(5), 541–543. doi:10.1097/00004583-198809000-00004

- Mamah, D., Owoso, A., Sheffield, J. M., & Bayer, C. (2014). The WERCAP screen and the WERC stress screen: Psychometrics of self-rated instruments for assessing bipolar and psychotic disorder risk and perceived stress burden. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 55(7), 1757–1771. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.07.004

- Mash, E. J., & Barkley, R. A. (Eds.). (2007). Assessment of childhood disorders (4th ed.). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

- McIntyre, R. S., Mancini, D. A., Srinivasan, J., McCann, S., Konarski, J. Z., & Kennedy, S. H. (2004). The antidepressant effects of risperidone and olanzapine in bipolar disorder. Canadian Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 11(2), e218–e226.

- McKay, D. (2019). Introduction to the special issue: Mechanisms of action in cognitive-behavior therapy. Behavior Therapy. Advance Online Publication. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2019.07.006

- McLeod, B. D., Jensen-Doss, A., & Ollendick, T. H. (Eds.). (2013). Diagnostic and behavioral assessment in children and adolescents: A clinical guide. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Meiser‐Stedman, R., Smith, P., Bryant, R., Salmon, K., Yule, W., Dalgleish, T., & Nixon, R. D. (2009). Development and validation of the Child Post‐Traumatic Cognitions Inventory (CPTCI). Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50(4), 432–440. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01995.x

- Ng, M. Y., & Weisz, J. R. (2016). Annual research review: Building a science of personalized intervention for youth mental health. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 57(3), 216–236. doi:10.1111/jcpp.12470

- Ogles, B. M., Melendez, G., Davis, D. C., & Lunnen, K. M. (2001). The Ohio scales: Practical outcome assessment. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 10(2), 199–212. doi:10.1023/A:1016651508801

- Osman, A., Bagge, C. L., Gutierrez, P. M., Konick, L. C., Kopper, B. A., & Barrios, F. X. (2001). The Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R): Validation with clinical and nonclinical samples. Assessment, 8(4), 443–454. doi: 10.1177%2F107319110100800409

- Pavuluri, M. N., Henry, D. B., Devineni, B., Carbray, J. A., & Birmaher, B. (2006). Child mania rating scale: Development, reliability, and validity. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 45(5), 550–560. doi:10.1097/01.chi.0000205700.40700.50

- Pelham, W. E., Jr., Gnagy, E. M., Greenslade, K. E., & Milich, R. (1992). Teacher ratings of DSM-III-R symptoms for the disruptive behavior disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 31(2), 210–218. doi:10.1097/00004583-199203000-00006

- Perrin, S., Meiser-Stedman, R., & Smith, P. (2005). The Children’s Revised Impact of Event Scale (CRIES): Validity as a screening instrument for PTSD. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 33(4), 487–498. doi:10.1017/S1352465805002419

- Pogge, D. L., Wayland-Smith, D., Zaccario, M., Borgaro, S., Stokes, J., & Harvey, P. D. (2001). Diagnosis of manic episodes in adolescent inpatients: Structured diagnostic procedures compared to clinical chart diagnoses. Psychiatry Research, 101(1), 47–54. doi:10.1016/S0165-1781(00)00248-1

- Posner, K., Brent, D., Lucas, C., Gould, M., Stanley, B., Brown, G., … Mann, J. (2008). Columbia-suicide severity rating scale (C-SSRS). New York, NY: Columbia University Medical Center. Retrieved from https://cssrs.columbia.edu/wp-content/uploads/C-SSRS_Pediatric-SLC_11.14.16.pdf

- Prokhorov, A. V., Pallonen, U. E., Fava, J. L., Ding, L., & Niaura, R. (1996). Measuring nicotine dependence among high-risk adolescent smokers. Addictive Behaviors, 21(1), 117–127. doi:10.1016/0306-4603(96)00048-2

- Reas, D. L., Whisenhunt, B. L., Netemeyer, R., & Williamson, D. A. (2002). Development of the body checking questionnaire: A self‐report measure of body checking behaviors. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 31(3), 324–333. doi:10.1002/eat.10012

- Reavy, R., Stein, L. A., Paiva, A., Quina, K., & Rossi, J. S. (2012). Validation of the delinquent activities scale for incarcerated adolescents. Addictive Behaviors, 37(7), 875–879. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.03.007

- Reed, D. L., Thompson, J. K., Brannick, M. T., & Sacco, W. P. (1991). Development and validation of the physical appearance state and trait anxiety scale (PASTAS). Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 5(4), 323–332. doi:10.1016/0887-6185(91)90032-O

- Richardson, C. G., Johnson, J. L., Ratner, P. A., Zumbo, B. D., Bottorff, J. L., Shoveller, J. A., … Prkachin, K. M. (2007). Validation of the dimensions of tobacco dependence scale for adolescents. Addictive Behaviors, 32(7), 1498–1504. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.11.002

- Rojahn, J., Rowe, E. W., Sharber, A. C., Hastings, R., Matson, J. L., Didden, R., … Dumont, E. L. M. (2012a). The behavior problems inventory‐short form for individuals with intellectual disabilities: Part I: Development and provisional clinical reference data. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 56(5), 527–545. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2788.2011.01507.x

- Rojahn, J., Rowe, E. W., Sharber, A. C., Hastings, R., Matson, J. L., Didden, R., … Dumont, E. L. M. (2012b). The behavior problems inventory‐short form for individuals with intellectual disabilities: Part II: Reliability and validity. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 56(5), 546–565. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2788.2011.01506.x

- Sachser, C., Berliner, L., Holt, T., Jensen, T. K., Jungbluth, N., Risch, E., … Goldbeck, L. (2017). International development and psychometric properties of the Child and Adolescent Trauma Screen (CATS). Journal of Affective Disorders, 210, 189–195. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2016.12.040

- Saxe, G., Chawla, N., Stoddard, F., Kassam-Adams, N., Courtney, D., Cunningham, K., … King, L. (2003). Child stress disorders checklist: A measure of ASD and PTSD in children. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 42(8), 972–978. doi:10.1097/01.CHI.0000046887.27264.F3

- Scott, K., & Lewis, C. C. (2015). Using measurement-based care to enhance any treatment. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 22(1), 49–59. doi:10.1016/j.cbpra.2014.01.010

- Shimokawa, K., Lambert, M. J., & Smart, D. W. (2010). Enhancing treatment outcome of patients at risk of treatment failure: Meta-analytic and mega-analytic review of a psychotherapy quality assurance system. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78, 298–311. doi:10.1037/a0019247

- Snaith, R. P. (2003). The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 1, 29. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-1-29

- Sorgi, P., Ratey, J. J., Knoedler, D. W., Markert, R. J., & Reichman, M. (1991). Rating aggression in the clinical setting: A retrospective adaptation of the overt aggression scale: Preliminary results. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 3(2), S52–S56.

- Southam-Gerow, M. A., Weisz, J. R., & Kendall, P. C. (2003). Youth with anxiety disorders in research and service clinics: Examining client differences and similarities. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 32, 375–385. doi:10.1207/S15374424JCCP3203_06

- Spence, S. H. (1995). Social skills training: Enhancing social competence with children and adolescents. Windsor, England: NFER-Nelson.

- Spence, S. H. (1998). A measure of anxiety symptoms among children. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36(5), 545–566. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(98)00034-5

- Stefanis, N. C., Hanssen, M., Smirnis, N. K., Avramopoulos, D. A., Evdokimidis, I. K., Stefanis, C. N., … Van Os, J. (2002). Evidence that three dimensions of psychosis have a distribution in the general population. Psychological Medicine, 32(2), 347–358. doi:10.1017/S0033291701005141

- Stein, L. A., Lebeau, R., Clair, M., Rossi, J. S., Martin, R. M., & Golembeske, C. (2010). Validation of a measure to assess alcohol-and marijuana-related risks and consequences among incarcerated adolescents. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 109(1–3), 104–113. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.12.015

- Stice, E. (2001). A prospective test of the dual-pathway model of bulimic pathology: Mediating effects of dieting and negative affect. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 110(1), 124–135. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.110.1.124

- Stice, E., Telch, C. F., & Rizvi, S. L. (2000). Development and validation of the eating disorder diagnostic scale: A brief self-report measure of anorexia, bulimia, and binge-eating disorder. Psychological Assessment, 12(2), 123. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.110.1.124

- Streiner, D. L., & Kottner, J. (2014). Recommendations for reporting the results of studies of instrument and scale development and testing. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 70(9), 1970–1979. doi:10.1111/jan.12402

- Swanson, J., Deutsch, C., Cantwell, D., Posner, M., Kennedy, J. L., Barr, C. L., … Wasdell, M. (2001). Genes and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Clinical Neuroscience Research, 1(3), 207–216. doi:10.1016/S1566-2772(01)00007-X

- Swanson, J. M., Schuck, S., Porter, M. M., Carlson, C., Hartman, C. A., Sergeant, J. A., … Wigal, T. (2012). Categorical and dimensional definitions and evaluations of symptoms of ADHD: History of the SNAP and the SWAN rating scales. The International Journal of Educational and Psychological Assessment, 10(1), 51–70.

- Tarren-Sweeney, M. (2013). The Brief Assessment Checklists (BAC-C, BAC-A): Mental health screening measures for school-aged children and adolescents in foster, kinship, residential and adoptive care. Children and Youth Services Review, 35(5), 771–779. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.01.025