Abstract

Following the Facebook-Cambridge Analytica scandal, the role that social media advertising can play in the outcomes of major elections is increasingly evident. While existing political advertising research has examined the influence of such adverts in contemporary election campaigns, there has been comparatively less research on the actual elements that make these adverts successful. The current study considers the extent to which different aspects of the political brand contribute to this success, particularly the use of the party leader as a heuristic device for voters and the strategic use of the “doppelgänger brand” phenomenon to undermine the opponent party’s campaign. By examining the adverts published on Facebook by the Conservative party and the Labour party in three key phases of the 2019 UK General Election, the importance of these two branding aspects in political social media advertising is investigated. The results show that the party that won the election, the Conservatives, made far greater use of both the leader heuristic and the doppelgänger brand phenomenon in their election adverts, and subtleties within the results reveal a novel finding for the use of the leader heuristic against the opponent party leader. The results are discussed in the context of election news coverage from 2019, and the ethical implications of treating deceptive campaigning techniques as successful are considered. The potential for the heuristics to be more powerful on alternative social media platforms with shorter-length content is also discussed as an avenue for future research to pursue.

Introduction

The Facebook-Cambridge Analytica scandal, in which the data of as many as 87 million Facebook users was secretly gathered and used to assist the 2016 presidential campaigns of both Donald Trump and Ted Cruz (Meredith Citation2018; Confessore Citation2018), shed light on two key issues. Primarily, it fueled greater public awareness of the value of personal data and how it can be used, particularly for targeted advertising, which involves prioritizing certain target demographics to view your adverts. Yet the scandal also revealed the immense power that social media platforms can have in shaping the outcomes of major elections. It is unsurprising therefore that social media has grown as an area of considerable interest for researchers in the political advertising field. Yet while much of this research has examined the influence of social media advertising in successful contemporary political campaigns (Metzgar and Maruggi Citation2009; Sani and Azizuddin Citation2014; Auter and Fine Citation2016), there is comparatively little research on the actual elements of these adverts that contribute to their success.

The effectiveness of social media advertising has been well demonstrated (Murdough Citation2009; Stelzner Citation2013), and as global social media usage continues to grow (Kemp Citation2021) as does election campaign spending on digital advertising. Dommett and Power (Citation2019) observed that digital advertising expenditure in UK elections increased from 1.7 per cent of overall advertising expenditure in 2014 to 42.8 per cent in 2017, where a total of over £3.16 million was spent by all political parties on Facebook advertising alone, far more than all other advertising channels combined. It is, therefore, increasingly important for both marketers and consumers to understand how political adverts on these platforms can manipulate voting behavior and the overall impact this can have on election outcomes.

This article will examine the existing research around two aspects of political marketing that have seen comparatively less coverage in the current literature – the use of the party leader as a heuristic device and the “Doppelgänger brand” phenomenon (Thompson, Rindfleisch, and Arsel Citation2006), and will evaluate the contribution of these aspects to the election strategies of both the Labour and Conservative parties in the 2019 General Election. Assessments of their effectiveness will then be made based on the success of each party’s election efforts and potential explanations for their efficacy in a social media environment will be discussed, as well as the implications of these findings for future elections.

Literature Review

Political Marketing

Political marketing refers to the amalgamation of two prominent fields of research – political science and marketing, and involves the application of traditional marketing concepts and techniques to political campaign strategy (Lees-Marshment Citation2001). The first major emergence of political marketing research was observed during the 1980s (Mauser Citation1983; Newman and Sheth Citation1985; Smith and Saunders Citation1990), where particular focus was given to the collaboration between the Saatchi and Saatchi advertising company and the Conservative Party for their 1979 General Election campaign – a notable early example of a political party employing the expertise and methods of a commercial marketing agency to improve their perception in voters’ minds and bolster their election performance (Grainger Citation2007). While the idea of applying long-established product-based marketing concepts to non-profit organizations was initially met with resistance from certain academics in the management science community who felt the conceptual integrity of the marketing discipline could be jeopardized (Tucker Citation1974; Arndt Citation1978), it soon became evident that, with some careful considerations (Lock and Harris Citation1996), valuable parallels could be drawn between the two areas. The electoral candidate, their numerous MPs and aides, and what they are offering for the voter can, for example, be viewed as the “product” being sold (Speed, Butler, and Collins Citation2015), just as the political party can function in the same way as a commercial brand in providing reassurance of quality and cultivating loyalty with their supporters (Peng and Hackley Citation2009).

Over time, political marketing has seen impressive growth as an area of research, both in its scope and its relevance, and has contributed to the development of several tools and concepts, such as impression management and brand equity, that are integral to a successful modern political campaign. One subject which has seen great depth in political marketing research is the political brand, particularly due to the accordance between academics in the field that both political parties and politicians can be sufficiently studied, and therefore managed, as brands (Kavanagh Citation1995; Reeves, de Chernatory, and Carrigan Citation2006; Spiller and Bergner Citation2011). The political brand is a multi-faceted concept that encompasses many key elements of marketing, from the more abstract aspects like brand identity and reputation (Speed, Butler, and Collins Citation2015; Gould Citation1998), to the tangible aspects of the political brand that are evident in campaign advertising, such as logos, party colors and images of the party leader (Scammell Citation2015). This study will focus on the latter and discuss the role these highly visible aspects of the political brand play in modern election campaigns, where the emergence of social media has drastically transformed the way that the political “product” is communicated to voters.

Branding

An intrinsic part of all advertising, including political campaigns, is branding, defined by the American Marketing Association (Citation2021) as “a name, term, design, symbol or any other feature that identifies one seller’s goods or service as distinct from those of other sellers.” From this perspective, successful branding is that which effectively separates the company from its competitors, and a brand’s memorability is a clear factor in this. Fischer et al. (Citation1991) investigated the memorability of brands with child participants and found that even those as young as three years old, with much less exposure to advertising than older participants, were surprisingly adept at recognizing the logos of notable brands. However, brands often serve a much broader purpose than simply differentiating a seller from its competitors – they provide meaning and indications of quality, while embodying the values that the company wishes to convey (Dean, Croft, and Pich Citation2015). This indication of quality is evident in a study by Robinson et al. (Citation2007), where children showed significant differences in self-reported taste and consumption of common food items when their packaging was manipulated to feature the McDonald’s logo. Not only have consumers been shown to infer quality from branding, but there is also evidence of consumers personifying brands and attributing humanlike characteristics and personalities to them – a phenomenon initially proposed by Aaker (Citation1997). This tendency for consumers to view brands like humans has sustained during the rise of digital commerce, and research has shown humanlike attributes are projected onto brands during virtual interactions on both websites (Shoebeiri, Mazaheri, and Laroche Citation2015) and social media platforms (Machado et al. Citation2019).

The influential power of brands has been partly attributed to the role of the brand as a heuristic device for consumers – a mental shortcut that allows consumers to make quick and cognitively economical decisions about which products to purchase and which companies to identify with (Ray et al. Citation1973; Park and Lessig Citation1981; Maheswaran, Mackie, and Chaiken Citation1992; Smith Citation2001). The concept of heuristics was first brought to prominence by Tversky and Kahneman (Citation1974), who described them as efficient but problematic solutions to decisions made under uncertainty, quite often leading to errors in prediction and estimation. Since then, the knowledge of heuristics has been advanced primarily in the field of economics, as well cognitive and consumer psychology, and a large range of heuristic devices have been identified.

The Political Brand as a Heuristic

The use of the brand as a heuristic device is evident in political advertising, where some research deems the average voter to be lacking the necessary information or incentive to engage in the thoughtful, often introspective processing needed to make a genuine decision about which party to vote for, instead opting for quick, efficient processing based on the salient elements of the political brand visible in their advertising (Clarke et al. Citation2004; Sniderman, Brody, and Tetlock Citation1991). This perspective is reflective of Fiske and Taylor (Citation1984) view of humans as “cognitive misers” who wish to expend as little of their cognitive resources as possible, an idea echoed in the “voter-centric” view of the political brand presented in Nielsen’s (Citation2015) review. Here, the voters themselves provide the brand with its meaning through the information they store in their memory which they associate with the brand. This information forms an “associative network,” with the activation of one piece of information, or “node,” activating other, associated nodes through a process called “spreading activation” (Anderson Citation1983; Keller Citation1993; Collins and Loftus Citation1975). Keller (Citation2003) suggests that, for a brand, these nodes can be anything from logos and taglines to values and attributes. As such, political brand managers are tasked with shaping these associative networks to guide the impressions of their party, eradicating negative associations and strengthening positive associations (Smith and French Citation2011).

Yet political brands differ from commercial brands in one crucial way – the inclusion of a leader. Commercial brands may have spokespeople or celebrity endorsements for promotional purposes, yet there is no expectation for these people to actually lead the company or make decisions (Speed, Butler, and Collins Citation2015). For political parties, however, the leader is a visible and tangible embodiment of the brand (Miller, Wattenburg, and Malanchuk Citation1986; Smith Citation2001), providing accessible and concise information from which voters can not only infer attributes about the party the leader represents, but also the ability of the leader to run their party and, potentially, the country. Clarke et al. (Citation2004) highlight how political parties are often diffused across national, regional and local organizations, which can create difficulty in communicating a single, clear message to voters. In comparison, the leader is an individual manifestation of the party, one that voters can rely on if the messages disseminated by the various levels of the political party are conflicting. As such, party leaders become a heuristic device themselves, allowing voters to make their decision based on the character of a person as opposed to a political brand which may lack coherence in its message. The rise of social media platforms has amplified this separation between party and leader, as politicians can now interact directly with their voters through their personal accounts (Bigi, Treen, and Bal Citation2016). Recent research by Mochla, Tsourvakas, and Vlachopoulou (Citation2023) examined the development of Greek politicians’ personal brands on the platform YouTube and found that, similar to earlier findings by Pich, Armannsdottir, and Dean (Citation2020), the politicians built strong personal brands by utilizing visual storytelling, emotional symbols such as flags and, crucially, through “authentic appearances” with the public. While such appearances can be powerful if executed correctly, perceived authenticity, or a lack thereof, can be catastrophic for politicians (Tolson Citation2001).

A political party must ensure that the message being conveyed by the images of their leader in any election campaign advertising is one of capability, since a lack of confidence in the leader equates to a lack of confidence in the party and weakens the links to favorable associations within the voter’s associative network for the party (Speed, Butler, and Collins Citation2015). The challenge for the leader, however, is to present themselves as sincere whilst in accordance with the values their party wishes to convey, in order to not damage the “brand authenticity.” Brand authenticity is an important concept in political campaigning, and refers to the extent to which the public believe that the message conveyed by both the leader and their party is a genuine reflection of their beliefs and not just an act (Tolson Citation2001). A lack of perceived authenticity can have detrimental effects on voters’ faith in a leader, and Tolson (Citation2001) attributes Tony Blair’s decline in the 2000s to this phenomenon. Dean, Croft, and Pich (Citation2015) describe the crucial gap between the “presented” and “authentic” brand as the “distance” between the values the party express in their campaign and the values their audience perceives them to actually have. If the authentic brand is not sufficiently aligned with the presented brand, voters begin to lose trust in the party. However, this gap also provides a valuable opportunity for opponent parties to improve their standing in the election, through the strategic use of the “doppelgänger brand” phenomenon.

Doppelgänger Brand

The concept of the doppelgänger brand was originally proposed by Thompson, Rindfleisch, and Arsel (Citation2006) and describes an alternative, negative view of a brand propagated by damaging news stories, satirical cartoons and, commonly, the use of a company’s own branding against them (Giesler Citation2012). The phenomenon occurs due to the incongruence between what a brand claims to be and what it is perceived by the public to be, and its success as a strategy to undermine a company’s attempts to convey a positive brand image is dependent on a substantial gap between the authentic and presented brand. It is often employed by activists to draw attention to political and social issues or to highlight the wrongdoings of popular companies, a recent example being the satirical adverts targeted at HSBC for their involvement in deforestation and fossil fuels, which used the identical colors, fonts and taglines as the genuine HSBC ad campaign at the time (Westwater Citation2020).

However, use of the doppelgänger brand phenomenon can also be seen in political campaigns. An essential historic example is the use of the phenomenon during the Labour party’s transition from “Old” Labour to “New” Labour, following Neil Kinnock’s 1983 election defeat. At that time, the Labour party was declining in popularity due to the harmful perception of them as the “loony left,” lacking a unified identity and unfit to lead – an idea effectively perpetuated by the media and scathing websites built on the fledgling internet. Labour used this troublesome perception to their advantage by actively acknowledging this view of their party and branding it “Old Labour,” creating a doppelgänger brand on which “New” Labour could blame the issues and failings of the party and distance themselves from the unpopular values that had become attached to the Labour brand story (Dean, Croft, and Pich Citation2015). More recently. during the 2019 general election, the Conservatives official Twitter account released an image mocking Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn by subverting the name and logo of KFC into “JFC,” with the tagline “Totally Spineless Chicken” (Hamilton Citation2019). While an example like this shows a party making use of iconic branding in order to achieve greater accessibility and humor in their adverts, more subtle, subliminal uses of a rival party’s branding elements are also seen quite often in political campaigns. Research into the impact of doppelgänger brand images on commercial brands has found evidence of reduced sales and increased mistrust towards the targeted company (Giesler Citation2012; Chhabra Citation2018), yet very little research has explored their impact on political brands and the election performance of political parties.

Given that these particular branding aspects have been insufficiently explored in political marketing research, this article will examine the use of both the party leader as a heuristic device and the strategic use of the doppelgänger brand phenomenon in the social media advertising of the two main parties in the 2019 UK general election, the Conservative Party and the Labour Party, in order to explore their contribution to the impact of political advertising on election performance. This election saw a considerable drop in the percentage of votes for the Labour Party compared to the previous election in 2017, from 40% to 32%, despite there being no change in party leadership. In comparison, the Conservatives received a slightly larger percentage of votes compared to the 2017 election, increasing from 42% to 44% (Baker and Uberoi Citation2019; Baker et al. Citation2019). An examination of the 2019 election could therefore provide an insight into the potential flaws of Labour’s marketing strategy, and the ways in which the Conservatives’ strategy was more successful.

Based on the fact that the Conservatives won the 2019 election, it is predicted that they will have made a greater use of both the leader heuristic and the doppelgänger brand in their advertising, particularly in the final, official election period, which increases in advertising, canvassing activities and press coverage (Deacon et al., Citation2019a,b,c,d,e) suggest is the most critical. Accordingly, the experimental hypotheses are as follows;

Hypothesis 1: The Conservatives will use significantly more of the leader heuristic in their advertising than Labour, and this difference will increase as the election campaign progresses.

Hypothesis 2: The Conservatives will use significantly more of the doppelgänger brand in their advertising than Labour, and this difference will increase as the election campaign progresses.

Additionally, this article will examine the effectiveness of the age-based targeted advertising strategies of both parties and explore whether it is more effective for a party to target their adverts towards the age groups who typically vote for them, or towards those that typically vote for their opponent.

Method

Materials

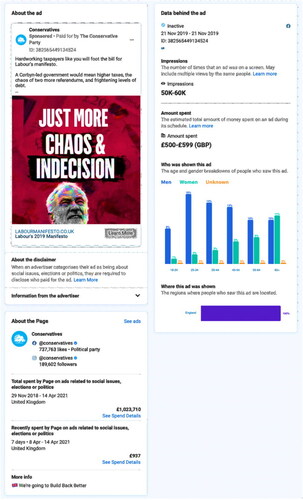

The primary data source used in the current study was the Facebook Ad Library (www.facebook.com/ads/library). This is an open-access library of all advertisements published on Facebook since May 2018 and provides details, among other things, of how much was spent on the ad, how many people were shown the ad and the demographics of those that viewed these ads (see Appendix). More detailed personal information about these Facebook users is not available.

Given that the Facebook Ad Library is a relatively nascent platform; it’s use as a data source in research is understandably scarce. While there have been studies analyzing the content of posts made from companies’ official Facebook pages (Jaichuen et al. Citation2019), or of third-party targeted ads that appear whilst visiting the Facebook pages of celebrities (Nkem et al. Citation2020), few have used the Facebook Ad Library to collect their data and have benefitted from the extensive data it has available. One notable study that made use of the library as its primary data source is Capozzi et al. (Citation2020) investigation of the portrayal of migration in Italy through Facebook ads. The study successfully used keywords to identify relevant ads and measured both the money spent on each ad as well as the number of “impressions,” or views, attained by the ad, and the demographics of these viewers, before performing content analysis on them. The present study employed a similar method, identifying relevant ads by filtering to only view those published by the two parties and measuring, among other variables, the impressions and money spent on the ad as well as performing content analysis on the ads themselves.

Sample

A total of 1011 ads were examined, of which 358 were published by the Labour Party and 653 were published by the Conservative Party. Inclusion criteria were for the ads to have been published between the 31st July – 12th December 2019 on the official Facebook pages of either the Labour or Conservative parties. These ads were split into three sub-samples depending on when they were published (1) 31st July – 14th September 2019, the period prior to the election being called; (2) 15th September – 29th October 2019, the period when the possibility of an election was being actively discussed and (3) 30th October – 12th December 2019, the official election period.

Labour published 160 adverts in Period 1, 63 in Period 2 and 175 in Period 3. The Conservatives published 86 adverts in Period 1, 17 in Period 2 and 550 adverts in Period 3.

Design

Data were cast into a 2 (Parties; Labour or Conservative) × 3 (Election period: 1 – 3) matrix. The primary focus was on the leader heuristic in the advert, which included either an image, name, or voice of Jeremy Corbyn or Boris Johnson. This was categorized as either promoting the party’s own leader or devaluing the opponent’s. Use of colors (red or blue) and the official Labour or Conservative logos and taglines were also recorded, as were other features including promotion of own party policies, the devaluation of opponent party policies and a “call for action.” The number of “impressions,” or views, attained by the advert were also measured, as were the amount of money spent on the advert and the number of adverts that used the same text and image, as well as the percentage of each demographic (gender and age) that were shown the advert on their Facebook feed.

Further information available from Facebook were the proportions by which ads were targeted towards gender and age groups. For ease of comparison in the present study both the impressions and money spent measurements, for which the data are only available as ranges, were grouped into ranked numerical categories, such as “100k–200k.” Each ad was scored with 0 (No) or 1 (Yes) for its inclusion of the various features in the dependent variable list and with 1, 2 or 3 depending on which election period it was first made active in. If an advert was made active on a date that overlaps two periods (i.e., 14th September and 29th October), it was classed as belonging to the earlier period. The “Use of Leader Heuristic” dependent variable was computed by combining the scores for “Promoting Own Leader” and “Devaluing Opponent Leader,” where at least one positive score on each feature meant a “Yes.” A data set was thus prepared for subsequent quantitative statistical analysis.

Statistics

A Pearson’s correlation was generated at the outset to examine the relationship between spending and election period. The data were then analyzed in a number of ANOVA tests with follow-up t-tests comparing the means for each dependent variable both between Labour and Conservatives at each period and within each party between election periods. For the follow up tests, alpha was shifted (from .05 to .01) to control the increased error rate caused by the large number of comparisons.

For the investigation into age-based advert targeting, mean percentages of targeting towards each age group from the Facebook Ad Library data were compared with data from a YouGov survey (Curtis Citation2019) on voting intent by age group. Since the age groups used by the two data sets were different, no attempts at statistical comparison were possible and therefore a qualitative analysis of the patterns of distribution was carried out.

Results

This study aimed to examine two elements of political social media advertising, the party leader as a heuristic device and the use of the “doppelgänger brand” phenomenon, and their contribution to the success of the Conservative party in the 2019 UK General Election.

In the interest of brevity, only significant findings are discussed. To assess whether the third election period was the most critical, a bivariate Pearson’s correlation (Election Period × Spending) was carried out. The analysis produced a small, significant correlation (r (1009) = .169, p < .001) which showed that spending was related to election period.

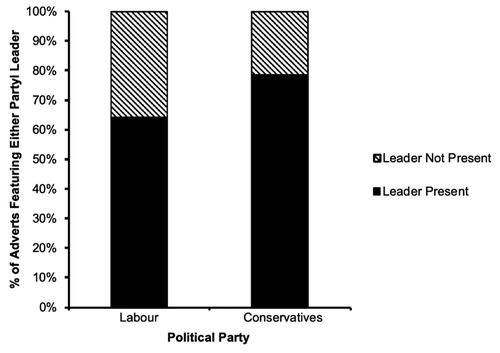

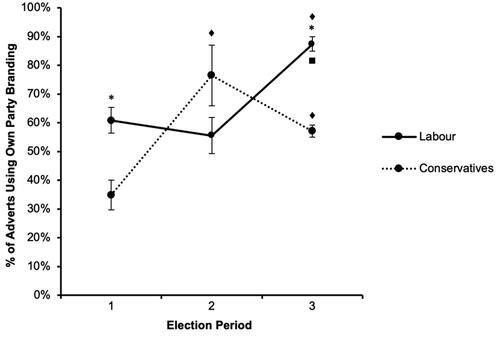

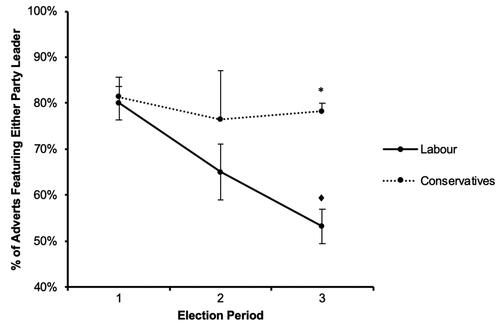

To investigate Hypothesis 1 (the Conservatives will use significantly more of the leader heuristic in their advertising than Labour, and this difference will increase as the election campaign progresses), descriptive statistics for the “use of leader heuristic” variable were first generated (), before an ANOVA (2 (Political Party: Labour or Conservatives) × 3 (Election Period: 1, 2 or 3)) was carried out. The results () revealed significant main effects of both political party (F (1, 1005) = 7.53, p = .006) and election period (F (2, 1005) = 8.85, p < .001) on the proportion of adverts that featured either party leader. There was also a significant political party × election period interaction observed (F (2, 1005) = 5.64, p = .004). Follow up t-tests revealed these differences to be due to two significant differences, these are as follows;

Figure 2. Percentage of adverts with either party leader present across the three phases of the election.

Firstly, the 120 Labour adverts in Period 1 (M = .80, SD = .40) featured significantly more of either party leader (t (286) = 5.10, p < .001) compared to the 175 Labour adverts in Period 3 (M = .53, SD = .50). Secondly, the 175 Labour adverts in Period 3 (M = .53, SD = .50) featured significantly less of either party leader (t (254) = −6.00, p < .001) compared to the 550 Conservative adverts in Period 3 (M = .78, SD = .41).

To further investigate this main hypothesis, separate analyses were carried out on the component dependent variables that made up the “use of leader heuristic” variable: “promoting own leader” and “devaluing opponent leader.”

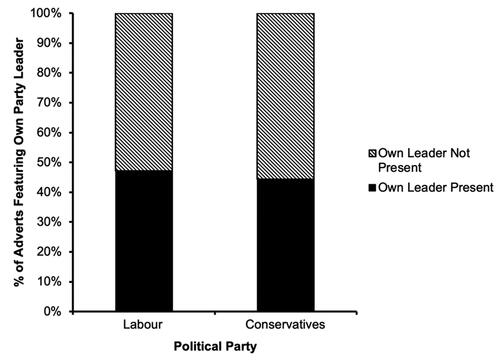

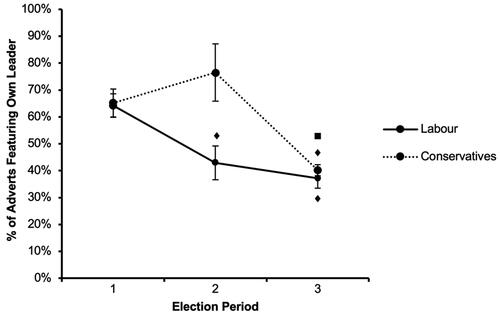

Descriptive statistics for the “promoting own leader” variable were first generated () followed by an ANOVA (2 (Political Party: Labour or Conservatives) × 3 (Election Period: 1, 2 or 3)). The results () revealed a significant main effect of election period (F (2, 1005) = 22.70, p < .001) on the proportion of adverts that showed the party’s own leader. Follow up t-tests revealed this main effect to be due to a number of significant differences, these are as follows;

The 120 Labour adverts in Period 1 (M = .64, SD = .48) featured significantly more of Jeremy Corbyn (t (181) = 2.81, p = .006) compared to the 63 Labour adverts in Period 2 (M = .43, SD = .50), and significantly more (t (293) = 4.72, p < .001) compared to the 175 Labour adverts in Period 3 (M = .37, SD = .49).

The 86 Conservatives adverts in Period 1 (M = .65, SD = .48) featured significantly more of Boris Johnson (t (115) = 4.47, p < .001) compared to the 550 Conservatives adverts in Period 3 (M = .40, SD = .49). The 17 Conservatives adverts in Period 2 (M = .76, SD = .44) also featured significantly more of Boris Johnson (t (17) = 3.36, p = .004) compared to the Conservatives adverts in Period 3 (M = .40, SD = .49).

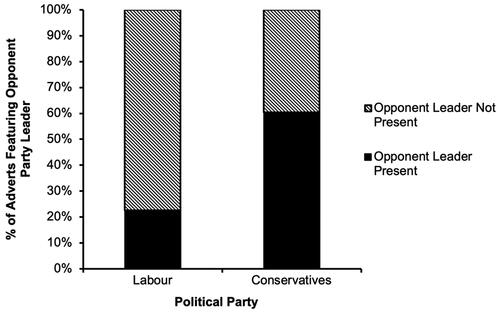

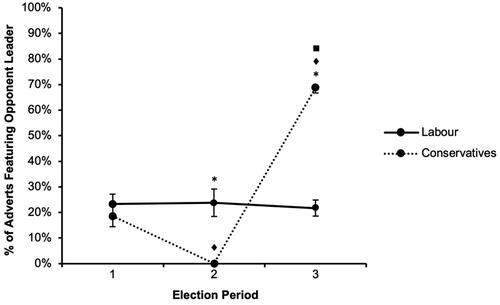

For the “devaluing opponent leader” variable, descriptive statistics were first generated (), before an ANOVA (2 (Political Party: Labour or Conservatives) × 3 (Election Period: 1, 2 or 3)) was carried out. Results () revealed a significant main effect of election period (F (2, 1005) = 31.38, p < .001) on the proportion of adverts that featured the opponent party leader. There was also a significant political party × election period interaction observed (F (2, 1005) = 35.61, p < .001). Follow up t-tests revealed these effects to be due to a number of significant differences, these are as follows;

Figure 6. Percentage of adverts with opponent leader present across the three phases of the election.

The 86 Conservatives adverts in Period 1 (M = .19, SD = .39) featured significantly more of Jeremy Corbyn (t (85) = 4.41, p < .001) compared to the 17 Conservatives adverts in Period 2 (M = .00, SD = .00), but featured significantly less of Jeremy Corbyn (t (126) = −10.75, p < .001) compared to the 550 Conservatives adverts in Period 3 (M = .69, SD = .46). The Conservatives adverts in Period 2 (M = .00, SD = .00) also featured significantly less of Jeremy Corbyn (t (549) = −34.74, p < .001) compared to the Conservatives adverts in Period 3 (M = .69, SD = .46).

The 63 Labour adverts in Period 2 (M = .24, SD = .43) featured significantly more of the opponent party’s leader (t (62) = 4.40, p < .001) compared to the 17 Conservatives adverts in Period 2 (M = .00, SD = .00). However, the 175 Labour adverts in Period 3 (M = .22, SD = .41) featured significantly less of the opponent party’s leader (t (325) = −12.71, p < .001) compared to the 550 Conservatives adverts in Period 3 (M = .69, SD = .46).

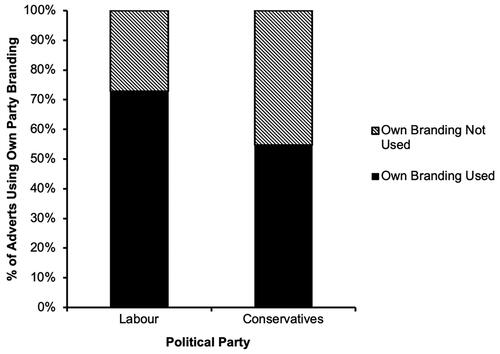

To investigate Hypothesis 2 (the Conservatives will use significantly more of the doppelgänger brand in their advertising than Labour, and this difference will increase as the election campaign progresses), descriptive statistics for the “use of own branding” variable were first generated (), followed by an ANOVA (2 (Political Party: Labour or Conservatives) × 3 (Election Period: 1, 2 or 3)). The analysis () revealed a significant main effect of election period (F (2, 1005) = 19.73, p < .001) on the proportion of adverts that used the party’s own branding. There was also a significant political party × election period interaction observed (F (2, 1005) = 7.27, p = .001). Follow up t-tests revealed these effects to be due to a number of significant differences, these are as follows;

The 86 Conservatives adverts in Period 1 (M = .35, SD = .48) featured significantly less Conservatives branding (t (24) = −3.53, p = .002) compared to the 17 Conservatives adverts in Period 2 (M = .76, SD = .44), and significantly less Conservatives branding (t (115) = −3.98, p < .001) compared to the 550 Conservatives adverts in Period 3 (M = .57, SD = .50). The 120 Labour adverts in Period 1 (M = .61, SD = .49) featured significantly less Labour branding (t (193) = −5.18, p < .001) compared to the 175 Labour adverts in Period 3 (M = .87, SD = .33). The 63 Labour adverts in Period 2 (M = .56, SD = .50) also featured significantly less Labour branding (t (82) = −4.69, p < .001) than the Labour adverts in Period 3 (M = .87, SD = .33).

The 120 Labour adverts in Period 1 (M = .61, SD = .49) featured significantly more of the respective party’s own branding (t (204) = 3.78, p < .001) compared to the 86 Conservatives adverts in Period 1 (M = .35, SD = .48). The 175 Labour adverts in Period 3 (M = .87, SD = .33) featured significantly more of the respective party’s own branding (t (437) = 9.24, p < .001) compared to the 550 Conservatives adverts in Period 3 (M = .57, SD = .50).

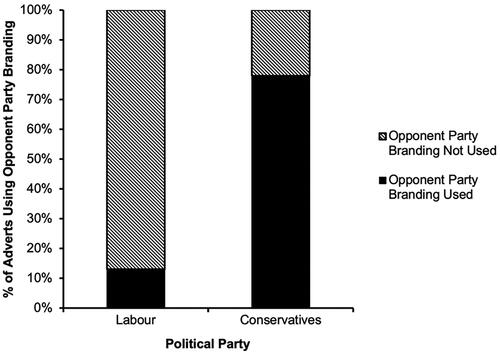

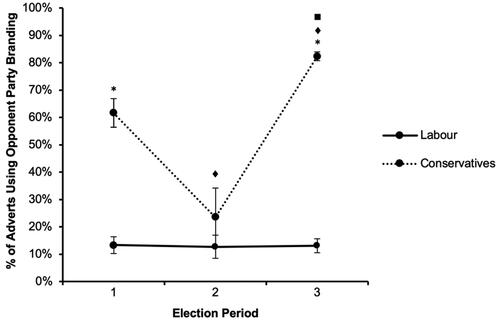

Descriptives were then generated for the “use of opponent branding” variable (), followed by an ANOVA (2 (Political Party: Labour or Conservatives) × 3 (Election Period: 1, 2 or 3)). The analysis () revealed significant main effects of both political party (F (1, 1005) = 112.41, p < .001) and election period (F (2, 1005) = 17.87, p < .001) on the proportion of adverts that used the opponent party’s branding. There was also a significant political party × election period interaction observed (F (2, 1005) = 17.61, p < .001). Follow up t-tests revealed these effects to be due to a number of significant differences, these are as follows;

Figure 10. Percentage of adverts using opponent party branding across the three phases of the election.

The 86 Conservatives adverts in Period 1 (M = .62, SD = .49) featured significantly more Labour branding (t (25) = 3.22, p = .004) compared to the 17 Conservatives adverts in Period 2 (M = .24, SD = .44), but significantly less Labour branding (t (102) = −3.76, p < .001) compared to the 550 Conservatives adverts in Period 3 (M = .82, SD = .38). The Conservatives adverts in Period 2 also featured significantly less Labour branding (t (565) = −6.24, p < .001) than the Conservatives adverts in Period 3 (M = .82, SD = .38).

The 120 Labour adverts in Period 1 (M = .13, SD = .34) featured significantly less of the opponent party’s branding (t (142) = −7.88, p < .001) compared to the 86 Conservatives adverts in Period 1 (M = .62, SD = .49). Similarly, the 175 Labour adverts in Period 3 (M = .13, SD = .34) featured significantly less of the opponent party’s branding (t (326) = −22.81, p < .001) compared to the 550 Conservatives adverts in Period 3 (M = .82, SD = .38).

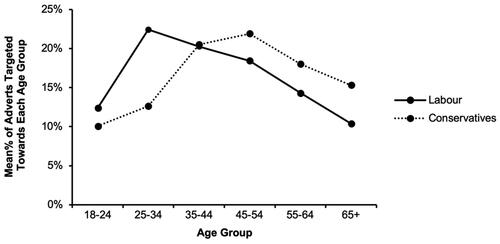

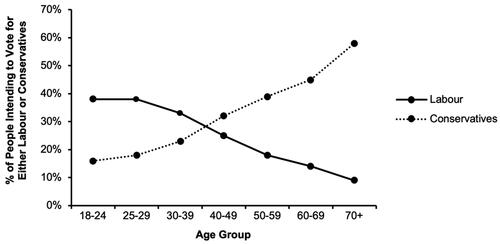

To investigate the effectiveness of the age-based targeted advertising strategies, mean percentages of each age group exposed to the adverts were generated and presented in , along with voting intention data by age from the YouGov survey (Curtis Citation2019) for visual comparison ().

Discussion

This study aimed to examine the elements of social media campaign adverts from two major political parties during the 2019 UK General Election. Particular focus was given to two aspects of the adverts, the use of the party leader as a heuristic device and the strategic use of the doppelgänger brand phenomenon. As expected, the Conservatives’ adverts made much greater use of the leader heuristic than Labour’s adverts did, particularly as the election date grew closer, yet this difference primarily emerged from the greater devaluation of the opponent party leader rather than the promotion of the party’s own leader. The Conservatives also made far greater use of the doppelgänger brand phenomenon, using Labour branding in the vast majority of their adverts. Hypothesis 1 can therefore be supported, but Hypothesis 2 is only partially supported, because despite the Conservatives using more of the doppelgänger brand than Labour, this difference did not steadily increase across the election campaign. Rather, there was a significant drop in the Conservatives’ use of the doppelgänger brand during Election Period 2. The Conservatives did, however, make much greater use of the doppelgänger brand in the third, official election period, which is supported by the correlational analysis on spending data as being the most critical.

As the Conservatives won the 2019 general election, it is a reasonable assumption to make that their marketing strategy was more successful than that of the Labour party. As such, the differences in the content and targeting of their Facebook adverts over the course of the election help to inform our understanding of what constitutes effective political social media advertising. A key difference highlighted by the analysis is the difference between the two parties in their use of the leader as a heuristic device in their adverts across the three phases of the election. The Conservatives used this heuristic device in the vast majority of their adverts and maintained this use at a similar level throughout the election. Labour, in comparison, used the leader heuristic increasingly less as the election went on, with just over half of their adverts featuring either party leader in the final, crucial period of the election. As such, Labour could exert far less influence over the associative networks surrounding both Boris Johnson and Jeremy Corbyn than the Conservatives (Anderson Citation1983; Keller Citation1993), who were largely free to shape the networks to align with the agenda they were pushing (Smith and French Citation2011). Crucially, the difference in use of the leader heuristic was also shown to emerge not from the Labour party’s insufficient promotion of Jeremy Corbyn, but from their lack of devaluation of the opponent leader, Boris Johnson. Throughout the election, only around a quarter of Labour adverts featured Boris Johnson, and while the Conservatives’ adverts showed similar rates for their inclusion of Jeremy Corbyn in the early phases of the election, they showed a pronounced increase once the election was officially called, with close to three quarters of their adverts in this period featuring Jeremy Corbyn. In fact, Jeremy Corbyn featured more frequently in the Conservatives’ total adverts than their own leader Boris Johnson did. This supports the effectiveness of using the leader as a heuristic device in political advertising, but not in the positive, promotive manner typically described in previous research (Speed, Butler, and Collins Citation2015; Clarke et al. Citation2004). Instead, this novel finding suggests that the most effective use of the leader heuristic is to devalue the opponent leader, impairing their perceived authenticity (Tolson Citation2001) and thereby polluting the representations held towards them in voters’ associative networks (Anderson Citation1983; Keller Citation1993). This creates a new, conflicting image of the leader in voters’ minds and serves to undermine the positive advertising attempts made by the opponent party, much like the second aspect examined in this article – the doppelgänger brand phenomenon (Thompson, Rindfleisch, and Arsel Citation2006).

Analysis of the use of this phenomenon revealed a very similar story. Labour used a greater proportion of their own branding in their adverts compared to the Conservatives, and their usage increased markedly during the official election period where almost all of their adverts featured their own branding. However, the Labour party’s use of Conservative branding was far lower, with less than a fifth of their adverts across the whole course of the election using the Conservatives’ colors, logos or taglines. In stark contrast, the Conservatives used Labour branding in over three quarters of their total adverts, and in an even larger proportion during the official election period. This is strong evidence of the power that the strategic use of the doppelgänger brand phenomenon can have in political advertising and suggests that the damaging effects on the targeted brand observed by Giesler (Citation2012) and Chhabra (Citation2018) extend to political brands as well as commercial brands. Since most of the Conservatives’ adverts that used Labour branding did so subtly, this could be an indication that the more discreet use of an opponent party’s branding elements is more successful in political advertising than the blatant, thought-provoking use typically seen in activist propaganda (Westwater Citation2020; Goodson Citation2012). This could be due to the Conservatives’ intention, as an official and right-wing party, to distance themselves from disruptive activists in order to maintain their reputation. Alternatively, it could be indicative of a strategic choice to favor the subliminal use of the phenomenon in order to prevent voters from being aware of its use at all, allowing for the implicit association of, for example, the color red with the word ‘chaos’ to cultivate in voters’ minds. Considering that both the Labour Party and the Conservative Party used opponent branding in a similar manner, it would appear that the Conservatives were more successful at cementing these negative associations simply because such a high proportion of their adverts featured Labour branding, again allowing them greater influence over voters’ associative networks around the Labour party (Smith and French Citation2011) . This, along with the novel finding about the malicious use of the leader heuristic, provides a rather cynical perspective that in political social media advertising, it is more effective to devalue the opponent party than to promote one’s own party. There is historic evidence for the efficacy of this approach, both from UK General Elections, when Saatchi and Saatchi’s “Labour isn’t Working” campaign was instrumental in turning the tables in favor of the Conservatives during the 1979 election (Grainger Citation2007), and from US Presidential Elections, a famous example being the “Willie Horton” advertisement used by Bush in his 1988 presidential campaign to portray his opponent Dukakis as being “soft on crime” (Newman Citation1999). It appears therefore that, had Labour campaigned as maliciously as the Conservatives in the 2019 General Election, they may have stood a better chance of winning.

This perspective is furthered by the finding that 88% of the Facebook adverts published by the Conservatives between the 1st and 4th of December 2019 were labelled as misleading by the UK’s primary fact-checking organization, Full Fact, compared to less than 7% of Labour adverts in the same timeframe (Dotto Citation2019). These adverts were able to be published without scrutiny due to Facebook’s policies on political advertising, and of the 653 Conservative adverts examined in the current article, only a handful were flagged by the Facebook Ad Library for having breached these rules. It appears therefore that social media platforms may represent an advertising environment like no other, where the typical regulations that protect against slander and misinformation do not apply. The marked increases in campaign budget dedicated to digital advertising (Dommett and Power Citation2019) clearly demonstrate that parties now view social media as one of the most important channels for election marketing. It is imperative therefore that these platforms receive the same scrutiny as traditional marketing channels in order to avoid a substantial detriment to the standards of future election campaigning.

The analysis of the age demographic data for each party’s adverts also offered an insight into how successfully the two parties targeted their adverts to the relevant audiences. By comparing the data provided by the Facebook Ad Library to a voting intention survey by YouGov (Curtis Citation2019) from the same election, it is clear that Labour chose to target their adverts towards those they expected would vote for them. They placed a sharp focus on younger voters, with the exception of the youngest age group (18–24), and increasingly less focus on older voters. The Conservatives, in comparison, appear to have planned their targeting in a more strategic way and focused not only on the older age groups that are typically more likely to vote for them, but also on age groups close to the “tipping point,” like the 35–44 year olds. The tipping point refers to the age where a voter becomes more likely to vote for the Conservatives over Labour, and data from YouGov surveys (Curtis Citation2019; Citation2017) of voting intention in the previous two general elections suggest this age is decreasing, from 47 in 2017 to 40 in 2019. This is reflected in the Conservatives’ targeting strategy, which peaks in the 45–54 age group, thus encompassing the tipping point of 47 from the previous election. This is not only evidence of a more informed and more effective advertising strategy employed by the Conservatives, but also of a shift away from class politics and towards age and identity-based politics.

There is additional evidence of this shift in the YouGov survey (Curtis Citation2019), with the observation that the majority of the “DE” social grade voted for the Conservatives in the 2019 election. This social grade encompasses both the working class and the non-working class (which includes the unemployed, state pensioners and lowest grade workers) and the majority of voters from this social grade have, historically, typically voted for Labour (Chorley Citation2019). This shift has important implications for future election campaigns, especially for the Labour and Conservative parties, since focusing on issues previously relevant to their target audiences may no longer be as impactful. This could provide some explanation for the recent Hartlepool by-election result, where the Labour Party lost a seat to the Conservatives which it had previously held for 62 years (Diver, Citation2021). For the Conservatives in particular, this move away from class politics brings with it a challenge to maintain their appeal to both the higher and lower social grades.

These findings all highlight failures in the strategy of Labour’s social media campaign that likely impeded their progress in the 2019 general election, yet whether these failures are simply the result of a misinformed marketing team is uncertain. There were reports from the previous election of deliberate sabotage by disgruntled staff at the Labour headquarters, who, by only targeting the proposed adverts towards him and his close associates, fooled Jeremy Corbyn into believing the Facebook election campaign had been implemented as planned when the real adverts shown to the public were entirely different (Shipman Citation2018). If true, this insubordination could be an indication of deep-rooted conflict within the party that could have meant campaigns like that in 2019 were purposely not executed to their full potential. It could be argued, however, that even with a stronger campaign strategy, the Labour Party’s efforts would still have been undermined by the overwhelmingly negative press coverage they received during the official election period. A series of reports from Deacon et al. (Citation2019a,b,c,d,e) examined the portrayal of all major parties in both television and print news coverage across the course of the official five-week election period. They assessed the extent to which each party was depicted in a positive or negative light in the press, and found that, from the outset, Labour were presented far less favorably than any other party. This negative portrayal worsened as the election date drew closer, culminating in the worst rating of all in the final week.

In comparison, the Conservatives were shown in a far more positive light to begin with and, despite being criticized throughout the first four weeks, were the only party whose portrayal actually improved during the final week of the election period. By comparing this to equivalent figures from the previous election in 2017, the report found that, towards the Conservatives, press hostility had halved in 2019, while it had more than doubled towards Labour. The abundance and reach of the press in the UK, particularly during elections (Fletcher, Newman, and Schulz Citation2020), means it is afforded considerable influence over the associative networks of voters (Anderson Citation1983; Keller Citation1993). As such, the negative portrayal of the Labour party by the UK press is likely to have weakened the positive associations the party tried to create, and could well have increased the crucial “distance” between the “authentic” and “presented” brand described by Dean, Croft, and Pich (Citation2015), thus facilitating the development of a doppelgänger brand image for the party that the Conservatives could take advantage of in their efforts to undermine Labour’s campaign.

The report also examined the coverage of individual Members of Parliament (MPs) during this period and found crucial differences between Labour and Conservatives. Ex-Labour MPs that had since switched allegiance to the Conservatives were given more coverage than Ex-Conservative MPs, which allowed for far greater opportunities for the disparagement of the Labour Party by notable figures. Additionally, while the proportion of all election news coverage that featured Boris Johnson (30%) was not much greater than that for Jeremy Corbyn (26%), the second most prominent Conservative MP, Sajid Javid, received only 3% of the coverage. In comparison, John McDonnell, Labour MP and Shadow Chancellor, received almost 8% of the coverage – a greater proportion than any of the other major party leaders including Jo Swinson, Nigel Farage and Nicola Sturgeon. As a result, Boris Johnson was highlighted above any other member of the Conservatives, with close to ten times the coverage of the next Conservative MP. Yet coverage of the Labour party was much more diffused across several members, leaving Jeremy Corbyn far less emphasized as the party leader. This difference would likely have contributed to the greater visibility of the Boris Johnson heuristic among voters and thus supports the impact of the leader heuristic on election performance.

It must be acknowledged that this account does not assume that advertising alone is powerful enough to determine the outcome of an election. However, in a context as muddled and overwhelming as a general election, images of political parties and their leaders provide clear, tangible information on which voters can base their decisions on, and, besides press coverage, party advertising and campaigning is the central channel by which these portrayals are disseminated.

In retrospect, the current study could have been improved in several ways had there not been constraints of time and practicality. Firstly, the sample distribution across the three election periods was far from equal. While this was largely due to the lack of adverts published by the Conservatives in the second election period, adverts from alternative platforms could have been included in the analysis in an attempt to make the sample distribution more equal. However, according to the central limit theorem (Wilcox, Citation2010), the overall sample sizes for both parties are large enough for the parameter estimates to follow a normal distribution, which suggests that the analysis is still robust despite the abnormal sample distribution across the three periods.

Secondly, the insight gained from the investigation into the use of the doppelgänger brand strategy could have been furthered by not only measuring whether or not an advert featured the opponent party’s branding, but also measuring what specific branding element was used in the advert. This could indicate what aspects of the political brand are more effective at influencing voters and could differentiate the two parties, beyond simply the proportion of their adverts, in their use of the doppelgänger brand strategy. Similarly, a follow-up experimental study would likely have provided a valuable insight into the effectiveness of the subliminal use of the doppelgänger brand by the two parties. Measuring the degree to which participants are aware of the opponent party branding elements present in the adverts, and how this awareness differs between elements (i.e., colors, logos, taglines), would likely contribute to an understanding of how attentive the average voter is towards these strategies and thus how much of an impact branding can make towards the implicit associations that political parties attempt to instill in voters. These considerations all represent potential avenues for future researchers to pursue and an examination of the use of the leader heuristic and the doppelgänger brand phenomenon in election campaigns outside of the UK could provide a valuable insight into the cultural differences in the application and impact of these two political branding aspects.

Conclusion

Overall, the current study found a wealth of evidence to suggest that the Conservatives’ advertising strategy during their 2019 general election campaign was far more informed and calculated than Labour’s strategy for the same election. Crucial differences were observed between the strategies in their use of heuristics, particularly the leader heuristic and the brand heuristic. However, these heuristics were not found to be used in the typical, promotive manner that the literature would predict, rather they were used by the Conservatives as effective vehicles for the disparagement of the Labour party and the defamation of its leader. By showing more of Jeremy Corbyn in their adverts than their own leader Boris Johnson, the Conservatives took a gamble and were dependent on instilling sufficient negative implicit associations about Corbyn in voters’ minds to outweigh the positive associations generated from Labour’s own campaign. This strategy clearly paid off, and with assistance from an overwhelmingly negative portrayal of Labour in the mainstream news, the Conservatives were able to create a significant distance between the “authentic” and “presented” Labour brand, allowing doppelgänger brand images of the party to circulate and, ultimately, facilitating the voters’ loss of faith in Labour and potentially swinging the election in their favor.

These results could have significant theoretical implications when considering the ethical dilemma that they raise. Political marketing is centered on what makes a successful political campaign, but “success” itself is ambiguous. One could see success simply as achieving the greatest proportion of votes in an election, while others may take the methods and tactics used into consideration when measuring the success of an election. The Conservatives clearly ran an effective campaign during the 2019 General Election, but if the success of their campaign was the result of their discrediting the opponent leader more than promoting their own, stealing aspects of the opponent party branding and spreading misinformation, the issue arises as to whether this should truly be seen as successful.

Facebook is a long-established social media platform and continues to hold the highest number of active monthly users worldwide (Dixon Citation2023). However, the emergence of newer platforms provides a compelling route for future research to pursue. While these newer platforms have subtle differences in how they exhibit their content, allowing political parties to issue their adverts in a variety of formats, there is a clear observable shift across platforms towards shorter, more immediate content. This trend is particularly evident on TikTok, a platform renowned for its quick videos and the ability for users to scroll endlessly. Considering the controversies around the spreading of misinformation within the app (Southwick et al. Citation2021) and the observation that the number of active monthly users worldwide has more than doubled since the 2019 election (Dixon Citation2023; Wang Citation2021), it is highly likely that TikTok will have a far greater influence on the next UK General Election than it did in 2019. Therefore, investigating whether the aforementioned heuristics have a stronger impact in the context of the shorter, more instant adverts that feature on TikTok could provide further insight into how these heuristics affect voters and inform regulations to limit the use of platforms like TikTok to manipulate voters in future elections.

Given that running a more malicious campaign is clearly shown here to be an effective strategy, looking ahead to the next UK General Election begs the question of what the most powerful counter-strategy would be. Under Starmer, Labour’s transition towards the political center (Burton-Cartledge Citation2021) has seen the differences between the two parties considerably diminish compared to 2019, making it much harder for the two parties to be critical of an opponent so akin to themselves. Whether Labour adopts a similar approach to denigrate their opposition or continues to run a more promotive campaign will be a powerful indication of the extent to which this marketing strategy is seen to be effective in modern day political campaigns.

References

- Aaker, J. L. 1997. “Dimensions of Brand Personality.” Journal of Marketing Research 34 (3):347–356 https://doi.org/10.2307/3151897 .

- American Marketing Association. 2021. Branding, April 6. American Marketing Association. https://www.ama.org/topics/branding/

- Anderson, J. R. 1983. The Architecture of Cognition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Arndt, J. 1978. “How Broad Should the Marketing Concept Be?” Journal of Marketing 42 (1):101–103 https://doi.org/10.2307/1250336

- Auter, Z. J., and J. A. Fine. 2016. “Negative Campaigning in the Social Media Age: Attack Advertising on Facebook.” Political Behaviour 38 (4):999–1020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109–016-9346-8

- Baker, C., and E. Uberoi. 2019. “General Election 2019: The Results.” UK Parliament, December 13. https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/general-election-2019-the-results-so-far/baker

- Baker, C., E. Uberoi, L. Audickas, N. Dempsey, O. Hawkins, R. Cracknell, R. McInnes, T. Rutherford, and V. Apostolova. 2019. “General Election 2017: Full Results and Analysis.” UK Parliament, January 29. https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-7979/

- Bigi, A., E. Treen, and A. Bal. 2016. “How Customer and Product Orientations Shape Political Brands.” Journal of Product and Brand Management 25 (4):365–372.

- Burton-Cartledge, P. 2021. “The Problems of Starmerism.” The Political Quarterly 92 (2):193–201

- Capozzi, A. M., G. F. Morales, Y. Mejova, C. Monti, A. Panisson, and D. Paolotti. 2020. “Facebook Ads: Politics of Migration in Italy.” International Conference on Social Informatics, pp. 43–57. Cham: Springer.

- Chhabra, S. 2018. “Understanding Doppelgänger Brand Image: The Darker Side to Emotional Branding.” In Driving Customer Appeal Through the Use of Emotional Branding, edited by R. C. Garg, pp. 303–311. Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

- Chorley, M. 2019. “General Election Results: Working Class Switched to Tories.” The Times, December 17. https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/general-election-results-working-class-switched-to-tories-kfwptc6cr

- Clarke, H. D., D. Sanders, M. C. Stewart, and P. Whiteley. 2004. Political Choice in Britain. Oxford: Oxford University Press on Demand.

- Collins, A. M., and E. F. Loftus. 1975. “A Spreading-Activation Theory of Semantic Processing.” Psychological Review 82 (6):407–428. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.82.6.407

- Confessore, N. 2018. “Cambridge Analytica and Facebook: The Scandal and the Fallout So Far.” The New York Times, April 4. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/04/us/politics/cambridge-analytica-scandal-fallout.html

- Curtis, C. 2017. “How Britain Voted at the 2017 General Election.” YouGov, June 13. https://yougov.co.uk/topics/politics/articles-reports/2017/06/13/how-britain-voted-2017-general-election

- Curtis, C. 2019. “2019 General Election: The Demographics Dividing Britain.” YouGov, October 31. https://yougov.co.uk/topics/politics/articles-reports/2019/10/31/2019-general-election-demographics-dividing-britai

- Deacon, D., J. Goode, D. Smith, D. Wring, J. Downey, and C. Vaccari. 2019a,b,c,d,e. “General Election 2019 Report 1: 7 November – 13 November 2019.” Loughborugh University, November 18. https://www.lboro.ac.uk/news-events/general-election/report-1/

- Dean, D., R. Croft, and C. Pich. 2015. “Toward a Conceptual Framework of Emotional Relationship Marketing: An Examination of Two UK Political Parties.” Journal of Political Marketing 14 (1/2):19–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377857.2014.990849

- Dixon, S. 2023. “Most Popular Social Networks Worldwide as of January 2023, Ranked by Number of Monthly active users.” Statista, February 14. https://www.statista.com/statistics/272014/global-social-networks-ranked-by-number-of-users/

- Dommett, K. and S. Power. 2019. “The Political Economy of Facebook Advertising: Election Spending, Regulation and Targeting Online.” The Political Quarterly 90 (2):257–265.

- Dotto, C. 2019. “Thousands of Misleading Conservative Ads Side-Step Scrutiny Thanks to Facebook Policy.” First Draft, December 6. https://firstdraftnews.org/latest/thousands-of-misleading-conservative-ads-side-step-scrutiny-thanks-to-facebook-policy/

- Diver, T. 2021. Tories take Hartlepool in historic Red Wall by-election victory Daily Telegraph 7th May https://www.telegraph.co.uk/politics/2021/05/07/tories-take-hartlepoolhistoric-red-wall-by-election-victory/

- Fischer, P. M., M. P. Schwartz, J. W. Richards, A. O. Goldstein, and T. H. Rojas. 1991. “Brand Logo Recognition by Children Aged 3 to 6 Years. Mickey Mouse and Old Joe the Camel.” JAMA 266:3145–3148.

- Fiske, S., and S. Taylor. 1984. Social Cognition. New York: Random House.

- Fletcher, R., N. Newman, and A. Schulz. 2020. “A Mile Wide, An Inch Deep: Online News and Media Use in the 2019 UK General Election.” Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism and University of Oxford, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

- Giesler, M. 2012. “How Doppelgänger Brand Images Influence the Market Creation Process: Longitudinal Insights from the Rise of Botox Cosmetic.” Journal of Marketin 76:55–68. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.10.0406

- Goodson, S. 2012. “Brandalism At The London Olympics.” Forbes, August 8. https://www.forbes.com/sites/marketshare/2012/08/08/brandalism-at-the-london-olympics/?sh=29b3e57e7aea

- Gould, P. 1998. The Unfinished Revolution. London: Little, Brown and Co.

- Grainger, R. 2007. “Saatchi and Saatchi and the Transformation of British Political Advertising: A Social Semiotic Analysis of the Conservative Party's 1979 General Election Poster Advertising.” Variety in Mass Communication Research 133–154

- Hamilton, R. 2019. “Why Everyone's in a Flap About the Tories’ JFC Stunt.” Creative Bloq, September 9. https://www.creativebloq.com/news/conservatives-jfc-stunt

- Jaichuen, N. V., V. Vongmonkol, R. Suphanchaimat, N. Sasiwatpaisit, and V. Tangcharoensathien. 2019. “Food Marketing in Facebook to Thai Children and Youth: An Assessment of the Efficacy of Thai Regulations.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16:1204. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16071204

- Kavanagh, D. 1995. Election Campaigning: The New Marketing of Politics. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

- Keller, K. L. 1993. “Conceptualizing, Measuring, and Managing Customer-Based Brand Equity.” Journal of Marketing 57:1–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299305700101

- Keller, K. L. 2003. “Brand Synthesis: The Multi-Dimensionality of Brand Knowledge.” Journal of Consumer Research 29 (4):595–600. https://doi.org/10.1086/346254

- Kemp, S. 2021. “Digital 2021: Global Overview Report.” DataReportal, January 27. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2021-global-overview-report

- Lees-Marshment, J. 2001. “The Marriage of Politics and Marketing.” Political Studies 49:692–713. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.00337

- Lock, A., and P. Harris. 1996. “Political Marketing – Vive La Différence!” European Journal of Marketing 30:14–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090569610149764

- Machado, J. C., L. Vacas de Carvalho, S. L. Azar, A. R. André, and B. P. Dos Santos. 2019. “Brand Gender and Consumer-Based Brand Equity on Facebook: The Mediating Role of Consumer-Brand Engagement and Brand Love.” Journal of Business Research 97:376–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.07.016

- Maheswaran, D., D. M., Mackie, and S. Chaiken. 1992. “Brand Name as a Heuristic Cue: The Effects of Task Importance and Expectancy Confirmation on Consumer Judgments.” Journal of Consumer Psychology 1:317–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1057-7408(08)80058-7

- Mauser, G. A. 1983. Political Marketing: An Approach to Campaign Strategy. New York, NY: Praeger.

- Meredith, S. 2018. “Facebook-Cambridge Analytica: A Timeline of the Data Hijacking Scandal.” CNBC, April 10. https://www.cnbc.com/2018/04/10/facebook-cambridge-analytica-a-timeline-of-the-data-hijacking-scandal.html

- Metzgar, E., and A. Maruggi. 2009. “Social Media and the 2008 U.S. Presidential Election.” Journal of New Communications Research 4 (1):141–165.

- Miller, A. H., M. P. Wattenburg, and O. Malanchuk. 1986. “Schematic Assessments of Presidential Candidates.” American Political Science Review 80:521–540. https://doi.org/10.2307/1958272

- Mochla, V., G. Tsourvakas, and M. Vlachopoulou. 2023. “Positioning a Personal Political Brand on YouTube with Points of Different Visual Storytelling.” Journal of Political Marketing. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377857.2023.2165214

- Murdough, C. 2009. “Social Media Measurement: It's Not Impossible.” Journal of Interactive Advertising 10:94–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2009.10722165

- Newman, B. I. 1999. The Mass Marketing of Politics. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Newman, B. I., and J. N. Sheth. 1985. “A Model of Primary Voter Behavior.” Journal of Consumer Research 12:178–187 https://doi.org/10.1086/208506

- Nielsen, S. W. 2015. “On Political Brands: A Systematic Review of the Literature.” Journal of Political Marketing 16 (2):118–146.

- Nkem, F., O. A. Chima, O. P. Martins, A. L. Ifeanyi, and O. N. Fiona. 2020. “Portrayal of Women in Advertising on Facebook and Instagram.” In RAIS Conference Proceedings, August 17–18, 2020, pp. 149–158. Princeton: Research Association for Interdisciplinary Studies.

- Park, C. W., and V. P. Lessig. 1981. “Familiarity and Its Impact on Consumer Decision Biases and Heuristics.” Journal of Consumer Research 8:223–230. https://doi.org/10.1086/208859

- Peng, N. and C. Hackley. 2009. “Are Voters, Consumers?” Qualitative Market Research 12 (2):171–186. https://doi.org/10.1108/13522750910948770

- Pich, C., G. Armannsdottir, and D. Dean. 2020. “Exploring the Process of Creating and Managing Personal Political Brand Identities in Nonparty Environments: The Case of the Bailiwick of Guernsey.” Journal of Political Marketing 19 (4):414–434.

- Ray, M. L., A. G. Sawyer, M. L. Rothschild, R. M. Heeler, E. C. Strong, and J. B. Reed, 1973. “Marketing Communication and the Hierarchy of Effects.” In New Models for Mass Communication Research, edited by M. Graney, and P. Clarke, pp. 147–176. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- Reeves, P., L. de Chernatory, and M. Carrigan. 2006. “Building a Political Brand: Ideology or Voter-Driven Strategy.” Journal of Brand Management 13 (6):418–428. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.bm.2540283

- Robinson, T. N., D. L. G. Borzekowzki, D. M. Matheson, and H. Kraemer. 2007. “Effects of Fast Food Branding on Young Children’s Taste Preferences.” Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine 161:792–797. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.161.8.792

- Sani, M., and M. Azizuddin. 2014. “The Social Media Election in Malaysia: The 13th General Election in 2013.” Kajian Malaysia 32:123–147.

- Scammell, M. 2015. “Politics and Image: The Conceptual Value of Branding.” Journal of Political Marketing 14:7–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377857.2014.990829

- Shipman, T. 2018. “Labour HQ Used Facebook Ads to Deceive Jeremy Corbyn During Election Campaign.” The Times, July 14. https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/labour-hq-used-facebook-ads-to-deceive-jeremy-corbyn-during-election-campaign-grlx75c27

- Shoebeiri, S., E. Mazaheri, and M. Laroche. 2015. “How Would the e-Retailer’s Website Personality Impact Customers’ Attitudes Toward the Site?” Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 23 (4):388–401.

- Smith, G. 2001. “The General Election: Factors Influencing the Branding Image of Political Parties and Their Leaders.” Journal of Marketing Management 17 (9/10):1058–1073. https://doi.org/10.1362/026725701323366719

- Smith, G., and A. French. 2011. “Measuring the Changes to Leader Brand Associations During the 2010 Election Campaign.” Journal of Marketing Management 27 (13/14):1304–1321. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2011.587825

- Smith, G., and J. Saunders. 1990. “The Application of Marketing to British Politics.” Journal of Marketing Management 5:295–306 https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.1990.9964106

- Sniderman, P., R. Brody, and P. Tetlock. 1991. Reasoning and Choice: Exploration in Political Psychology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Southwick, L., S. C. Guntuku, E. V. Klinger, E. Seltzer, H. J. McCalpin, and R. M. Merchant. 2021. “Characterizing COVID-19 Content Posted to TikTok: Public Sentiment and Response During the First Phase of the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Journal of Adolescent Health 69 (2):234–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.05.010

- Speed, R., P. Butler, and N. Collins. 2015. “Human Branding in Political Marketing: Applying Contemporary Branding Thought to Political Parties and Their Leaders.” Journal of Political Marketing 14 (1–2):129–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377857.2014.990833

- Spiller, L., and J. Bergner. 2011. Branding the Candidate: Marketing Strategies to Win Your Vote. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO.

- Stelzner, M. 2013. “The 2013 Social Media Marketing Industry Report.” The Social Media Examiner. http://www.socialmediaexaminer.com/SocialMediaMarketingIndustryReport2013.pdf

- Thompson, C., A. Rindfleisch, and Z. Arsel. 2006. “Emotional Branding and the Strategic Value of the Doppelgänger Brand Image.” Journal of Marketing 70:50–64. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.70.1.050.qxd

- Tolson, A. 2001. “‘Being Yourself’: The Pursuit of Authentic Celebrity.” Discourse Studies 3 (4):443–457. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445601003004007

- Tucker, W. T. 1974. “Future Directions in Marketing Theory.” Journal of Marketing 38 (2):30–35. https://doi.org/10.2307/1250194

- Tversky, A., and D. Kahneman. 1974. “Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases.” Science 185:1124–1131. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.185.4157.1124

- Wang, E. 2021. “TikTok Hits 1 Billion Monthly Active Users Globally – Company.” Retrieved May 2023, from Reuters, September 27. https://www.reuters.com/technology/tiktok-hits-1-billion-monthly-active-users-globally-company-2021-09-27/

- Westwater, H. 2020. “Fake Billboards Target HSBC Over ‘Climate Colonialism'.” The Big Issue, November 3. https://www.bigissue.com/latest/fake-fossil-bank-billboards-target-hsbc-over-climate-colonialism/

- Wilcox, R. R. 2010. “Fundamentals of modern statistical methods: Substantially improving power and accuracy (Vol. 249).” New York: Springer.