Abstract

The current study investigated adolescents’ (N = 213) decision finding processes and affective reactions to interactions on social media via 29 focus groups. As part of a larger study, adolescents participated in focus groups at two time-points across an academic year while participating in a school-based intervention promoting healthy romantic, interpersonal, and family relationships, job readiness, and financial literacy. Qualitative analyses indicated adolescents’ experiences and decisions on social media platforms were informed by their awareness of audiences, namely who they thought would view their posts and anticipated responses from “friends,” “family members,” “fans,” “creeps,” and “potential employers.” Comprehensive school-based interventions may serve to effectively develop responsibility more broadly, as well as a specific awareness about online risks and behaviors.

Approximately 95% of U.S. adolescents have access to a smartphone, and half report that they use their devices constantly throughout the day (Anderson & Jiang, Citation2018). The use of social media and networking websites such as Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok have become widespread and allow sharing of personal content such as photos, pieces of writing, or videos with both curated and mass audiences (Bányai et al., Citation2017). Despite meeting a variety of needs related to social connection and belongingness for adolescent users, these technologies also pose multiple social, psychological, and potentially economic risks (Ahn, Citation2011; Bányai et al., Citation2017). Understanding adolescents’ social media usage is important because adolescence is a developmental period during which social and emotional maturation often occurs; however, adolescents’ ability to accurately evaluate long-term risks may be impaired due to lack of experience and a developing prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for gathering and adapting to information, including emotional input (Cohen et al., Citation2016; Selman, Citation1981). School-based interventions that seek to promote adolescents’ intrapsychic and interpersonal resilience have been identified as potentially valuable mechanisms for bolstering well-being and reducing engagement in risky illicit drug use, sexual behaviors (e.g., engaging in sexual relationships), or increased appropriate behaviors like use of violence prevention strategies, drug refusal, and emotional awareness (Curran & Wexler, Citation2017). Yet, less is known about how such programs influence social media usage, online decisions, and behavior. Therefore, the current investigation sought to provide insights into how the strategies adolescents employ in navigating online social media develops in the context of involvement in a comprehensive curriculum that focuses on healthy relationships, job readiness, and financial literacy.

Adolescent connection and risk in online environments

Online environments have become, for many adolescents, a critical context in which they seek to form connections and develop a sense of belongingness (Nadkarni & Hofmann, Citation2012). Although most contemporary social media platforms were initially developed as informal mechanisms for communicating and sharing creative content among friends and acquaintances, the widespread adoption of Internet and social media technologies has now contributed to the development of a wider culture of connectivity where informal aspects of social life are widely viewable by much larger groups (van Dijck, Citation2013). The impact on adolescence has been particularly profound because adolescence is a developmental period in which individuals begin to intentionally differentiate from their family of origin and explore how to effectively develop and navigate peer relationships (Santrock, Citation2018). Now, early attempts to navigate social interactions can be saved and linked to an adolescent in a perpetual digital archive, which suggests that consequences of adolescent social decisions may be amplified for themselves and throughout their peer networks (Yau & Reich, Citation2019). For example, an adolescent’s early attempts to flirt or build intimacy with a romantic interest can be image-captured and used as the basis to engage in “sextortion” through the threat or actual sharing of such images to wider publics (Patchin & Hinduja, Citation2020). Likewise, posts that involve problematic material, such as drug and alcohol use, or offensive jokes or commentary have increasingly been utilized by employers as the basis for firing (or never hiring potential) employees, even if such digital content was posted many years previously (Hidy & McDonald, Citation2013).

Adolescents’ developing ability to assess risks and long-term consequences may make them especially susceptible to social media’s negative consequences (Yang et al., Citation2018). Adolescents often display behaviors on social media that reflect their peer experiences but may not align with what adults would approve. For example, adolescents’ self-reported use of alcohol is linked to their self-presentations with alcohol on social media, suggesting adolescents may not engage in extensive self-censorship on social media regarding potentially illegal behaviors (Moreno et al., Citation2010). Adolescents may be aware that their peers can see their posts, and some may use privacy control settings as a tool to manage their image; however, such controls are limited and many users may not have an accurate perception of the security of their data (Baccarella et al., Citation2018). Specifically, many adolescents may be unaware of the type of information that is associated with them, such as their private messages, location, data from health apps and other websites they visit, products they have purchased, and even facial recognition (Marwick & Boyd, Citation2014; Matsakis, Citation2019). Consequences of intentionally or unintentionally disclosing inappropriate material on social media can range from benign forms of peer gossip and invasions of privacy to more serious consequences such as losing a job or promotion opportunities, being sexually harassed, experiencing cyberbullying, and being stalked (Drouin et al., Citation2015; Salter, Citation2016). The differences in how adolescents recognize these consequences may depend on where they are in their development of interpersonal competence, or how they understand who is impacted by their interactions with others (Selman, Citation1981).

Many adolescents describe some awareness of the potential risks of social media usage, noting that social media can be a place for cyberbullying—as well as a source of stress, low self-esteem, addictions, and negative emotions (O’Reilly et al., 2018). Yet, accurately assessing the risks of certain online activities can be a difficult task for many adolescents. Compared to previous developmental stages, adolescence requires navigating more complex emotional experiences and peer influences, along with extensive physical changes (Romer et al., Citation2011; Santrock, Citation2018). Adolescent risk-taking behaviors may be influenced by desires to belong within peer-groups as well as a burgeoning frontal cortex that amplifies the salience of exciting and novel experiences while attenuating long-term consequences (Romer et al., Citation2011; Shulman et al., Citation2016). As such, adolescence may represent a time that is ripe for interventions aimed at facilitating increased awareness of the online landscape and how to successfully navigate it.

Comprehensive school-based interventions may be one form of intervention that could help adolescents gain knowledge and awareness of challenges in online spaces and develop a variety of additional strengths and skills (Curran & Wexler, Citation2017). Increasingly, scholars and practitioners have recognized the improved efficiency and effectiveness of implementing wide-ranging interventions that develop positive skills and socio-emotional development broadly, rather than implementing multiple focused interventions for each positive or negative behavior adults hope to encourage (or discourage) among adolescents (Curran & Wexler, Citation2017; Taylor et al., Citation2017). Many risky and health-compromising behaviors (e.g., drinking/drug use, risky sexual behavior, aggression, poor academic achievement) in which adolescents engage are highly correlated and interconnected with one another (Flay, Citation2003). Such behaviors likely have similar underlying causes, and as such, scholars have suggested challenges faced by many adolescents may be most effectively changed through comprehensive and global (rather than more targeted or behavior-specific) programming (Flay, Citation2003). A recent meta-analysis has demonstrated long-term benefits of school-based interventions for social-emotional skills, well-being, graduation rates, and safe sexual behaviors (Taylor et al., Citation2017). However, whether such wide-ranging school-based interventions might also hold benefits or promise for helping adolescents navigate their increasingly digital world is unknown and warrants further study.

Social information processing theory and the development of interpersonal competence

In exploring how comprehensive school-based interventions might impact adolescents’ online behavior, we drew on Social Information Processing Theory (Crick & Dodge, Citation1994). Social Information Processing Theorists (SIPTs), contend human behavior both in general, but also particularly in online settings, is often driven by complex interactions between cognitions (i.e., how one interprets, understands, and expects the world around them to operate) and emotions (i.e., one’s emotional state and feelings; Lemerise & Arsenio, Citation2000; Walther, Citation2015). SIPTs suggest that humans hold a cognitive schema of how they expect interactions to unfold in both in-person and online settings and make decisions about how to react to or engage in such settings based in part on consequences they anticipate occurring (or actually experience) in response to their behavior (Lemerise & Arsenio, Citation2000; Walther, Citation2015).

In addition to this role of cognitions, SIPTs propose emotions serve to orient individuals’ attention by emphasizing or de-emphasizing certain forms of information gathered and attended to, or in prioritizing the consequences seen as desirable (or undesirable; Lemerise & Arsenio, Citation2000). For example, when meeting someone for the first time, SIPTs would contend that individuals have in their head a cognitive schema for how they would expect others to react to various behaviors, such as a firm handshake, a warm embrace, or a grumbling acknowledgement. Which of these behaviors an individual actually engages in will depend in part on their cognitive goals for the interaction (e.g., to welcome, to intimidate, to connect) and potentially on their emotional state (e.g., whether they are happy, nervous, angry, or scared). As such, this investigation sought to specifically elucidate the structure of adolescents’ cognitive schemas for interacting on social media, and to explore the role of both cognitions and emotional affect when engaging in these spaces over time.

How these cognitive schemas are formed and shift throughout life may be influenced by developmental level. Selman’s (Citation1981) theory on interpersonal competence may help in understanding how adolescents are processing social interactions. Selman (Citation1981) posits that later in development, around adolescence, reactions to interpersonal interactions involve understanding that the self and others involved have different reactions to these interactions and these reactions can influence the thoughts and feelings an individual has about the other person. Particularly, a third party, or what might be considered an “audience member” for the sake of this study, is recognized as an influence in interpersonal interactions (Selman, Citation1981). Further, these reactions can depend on the context of the situation (Selman, Citation1981), which relevant to this study, could be a distinction between the setting of social media and real-life situations.

Overview of the present study

Adolescents spend increasingly large amounts of time socially interacting in digital environments (Anderson & Jiang, Citation2018), a reality likely further exaggerated by the COVID-19 pandemic. In order to effectively serve adolescents, it is critical that designers and implementers of school-based interventions understand the factors that inform adolescent behavior in such environments. The ways in which current interventions and practices may (or may not) translate to online settings should also be considered. The current study sought to answer two overarching research questions regarding adolescents’ use and engagement with social media platforms. Our first question, informed by Social Information Processing Theory (Crick & Dodge, Citation1994; Lemerise & Arsenio, Citation2000), was: How do adolescents make decisions about and affectively experience interactions on social media platforms? Given our interest in the potential utility of school-based interventions in positively impacting responsible decision-finding in online contexts, our second research questions was: In what ways do students’ approaches to social media use change over the course of their involvement with a comprehensive school-based program?

Method

Study design and context

To answer our research questions, we conducted an analysis of focus group data collected from adolescents who participated in the Champaign Area Relationship Education for Youth (CARE4U) program. CARE4U, a comprehensive school-based intervention, implemented in 5 high schools in a midsize Midwestern city. The intervention was voluntary and occurred during students’ lunch period or life skills class, depending on the school. CARE4U occurred over the course of the academic year focusing on relationship education using the Love Notes 2.1 curriculum (Pearson, Citation2016) in the fall semester, and addressing job readiness and financial literacy using the Road to Success curriculum (authors blinded) during the spring semester. Focus groups were conducted for each classroom at the end of each respective curriculum in December 2018 (Post Love Notes 2.1), and again in April 2019 (Post Road to Success). Upon completing all lessons part of CARE4U, participants had the option to enroll in a fully-funded local community college course or engage in an 8-week summer work experience related to their anticipated career field. Therefore, interested participants were often those around working age or thinking about college preparation.

Description of school-based intervention

For the program involved in this study, the Love Notes 2.1 curriculum, delivered during the fall semester, consisted of 10 lessons over the course of a semester. High school students met in a classroom setting and discussed these lessons with a trained program facilitator. Facilitators had master’s level training in human services fields such as education, social work, or public health, and were assisted by psychology undergraduate and school psychology graduate students who had mandated reporter and domestic violence training. The lessons in this curriculum began with self-discovery and included conversations surrounding a “Relationship Vision” for oneself, values desired in relationships, baggage from past relationships or life events, and related topics. The lessons progressed into understanding red flags of relationships, how to communicate needs and handle conflict, and how to wait before making major decisions like buying a house, car, or pet within the first few months of dating. Videos and other forms of media, as well as scenarios and hands-on activities were part of this intervention.

The Road to Success curriculum (authors blinded) is a set of lessons targeting financial literacy and job readiness. Similar to the structure of Love Notes 2.1, high school students met in a classroom setting with a trained facilitator to complete this curriculum over the course of the spring semester (following the Love Notes 2.1 curriculum). Road to Success included 10 lessons, most of which were focused on job readiness, with three lessons about financial literacy. Job readiness lessons taught students how to format and write a résumé, skillfully complete an interview, deliver elevator speeches, and similar topics. Financial literacy lessons followed the job readiness lessons and taught students how to make S.M.A.R.T. goals, develop spending plans, and identify how relationships and money may interact. The curriculum ended with a review lesson on the topics discussed. This part of the program was not a focus of our study, but we include this information for context.

Treatment integrity was evaluated across both programs. Specifically, immediately after each lesson, treatment integrity forms were completed via Qualtrics by an undergraduate or graduate research assistant and the facilitator of the group. to provide information about components that were included (i.e., yes/no) in the lessons, activities completed, general objectives that were met in accordance with program goals, and student engagement during the session. Participant engagement was rated by each Project Facilitator, as well as student helpers at the end of every CARE4U session to provide information about how engaged students were during the lesson.

Participants

Participants were adolescents (N = 213) involved in the CARE4U program. Participants were recruited for the CARE4U program through tabling at their school registration days, referrals from school counselors and social workers, word of mouth from previous participants in CARE4U program, and enrollment in a class in which the intervention took place (i.e., Life Skills). An overview of CARE4U participant demographics can be seen in . Participants were predominately female (67%), identified as Black/African American (55%), and were at the time currently enrolled in either 10th (41%) or 11th grade (37%). Most spoke English as the primary language within their household (87%), though some had learned English as a second language, and reported other languages including Spanish, French, Korean, and Chinese, as the primary language used in their household. The racial and ethnic makeup of participants were slightly different than the racial and ethnic makeup of the overall student population at each high school, as the high schools we sampled from had between 28-37% Black/African American students in 2018. Focus group participation ranged from 7-24 adolescents (M = 13.68).

Table 1. Participant demographics (N = 213).

Focus group questions and data collection

In December 2018, 14 focus group interviews (N = 205) were conducted following adolescents’ completion of the Love Notes 2.1 intervention. In April 2019, 15 additional focus groups (N = 184) examined the same topics following completion of the Road to Success curriculum. All participants in the intervention were invited to participate in the focus groups, however, some participants involved in the program did not participate either due to being absent from school the day of data collection, other scheduling conflicts, or attrition [e.g., they moved, could no longer fit the intervention meetings in their school schedule, or lost interest in the program]. Analyses for this investigation focused on participants’ responses to two broad questions regarding their social media use experiences. These questions were: “What influences your social media activity?” and “How does social media make you feel?” which were followed up with probes about how CARE4U influenced their social media activity, and about feelings they experienced in response to their own posts, others’ posts, and responses to their posts. Focus group interviews lasted on average about 22 min (M = 22.38) and were conducted by a faculty member or graduate research assistant author and one to two undergraduate research assistants. Researchers verbally reminded participants about informed consent after obtaining parent permission and written child assent. Approval from the authors’ university Institutional Review Board was obtained.

Data coding and analysis

Data were analyzed using an inductive constant comparative method to code, categorize, and evaluate themes (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2015) within adolescents’ discussions of their use, affective response, and cognitions about social media. In the first step of analyses, data from focus groups were transcribed verbatim by undergraduate and graduate research assistants. Next, transcript excerpts pertaining to social media (i.e., in response to the social media questions outlined previously), were independently read and coded by members of the research team following Corbin and Strauss (Citation2015) guidelines for line-by-line coding. At this stage of the coding process, participants’ own words (direct quotes) were used to develop a preliminary coding scheme grounded in the language of the participants. For example, the quote “I follow my family on social media, and I don’t wanna post something that I won’t approve of, and they won’t approve of” was assigned codes I follow my family on social media, and I don’t wanna post something I and [my family] won’t approve of. Whereas the quote “Friends and family influence your social media activity. Anything from posting, to commenting, to liking, to deleting, the whole gamut” was given the code friends and family influence your social media posting, commenting, liking, and deleting. These initial themes were presented to facilitators of the intervention, as well as members of the Advisory Board for CARE4U, which included school and social service agency personnel, parents of students, and community employers from diverse ethno-racial, socioeconomic, and educational backgrounds. Feedback from these meetings reflected a similar understanding to the authors’ interpretations and were utilized to help guide/direct our analyses.

Next, line-by-line codes were grouped into related categories that represented shared concepts. For example, the aforementioned line-by-line codes were combined into a category labeled “Family” which was noted in research memos as an important audience that participants reported influenced their posting habits. During weekly team meetings, the research team iteratively developed a shared codebook based on categories identified and ensured at least 90% agreement across independent coders of each transcript. As categories were identified and revised, the research team sought to evaluate the dimensionality of categories and how categories were theoretically related to one another through a process of comparative analysis (i.e., axial coding). In this project, due to the content of student responses, much of this process involved mapping out other sorts of audiences mentioned by participants as fans, friends, employers, and creeps, (people the participant may not know or want to be viewing their social media posts) and exploring how participants described the ways those audiences impacted their use and experience of social media outlets. To accomplish this, weekly team meetings were used to evaluate similarities and differences across focus group excerpts, propose theoretical relationships, and then assign team members to return to transcripts to evaluate whether the proposed relationships or hypotheses aligned with the data. To assess changes over time, particular attention was given to similarities and differences across waves of focus groups. Our final coding scheme can be found in Appendix A. Ultimately a core theme of “awareness of audiences” emerged as a critical concept grounded in the data and that captured the core nature of information shared by students about their social media experiences.

Positionality statement

With respect to the positionality of the coders,—the majority of the undergraduate and graduate students coding the data were white and identified as women. Further, all coders were engaged in higher education learning while coding, under the supervision of white, upper middle class faculty members who identified as men. These identities were different from the participants, the majority of whom described themselves as Black girls and reported a lower socioeconomic status. This positionality was acknowledged and considered during the coding process, as open discussions about accurate interpretations and follow-up focus groups took place. In addition, because of these variations in social positions, the research team took several steps (noted previously) to member check (Lub, Citation2015) with participants, members of the program advisory board, and program implementation team who were themselves members of the research population and their local community.

Results

Across focus groups, when adolescents explained what drove their decision-finding and affective experiences of using social media platforms, their responses centered around who they expected to view the content they shared and their anticipated or actual responses to that content. We labeled this core concept “awareness of audiences.” Adolescents’ “awareness of audiences” functioned as an anticipatory cognitive schema that adolescents drew upon in order to determine what they should (or should not) post to variable social media platforms. Students explained that their awareness of audiences was generally driven by either their experiences in online settings, or by knowledge shared by others, either their peers, family members, or occasionally teachers and facilitators of CARE4U.

Adolescents reported considering how these audiences might infer something about their personality or activities based on content shared, and often sought to elicit certain forms of responses or impressions from different groups. For example, one student indicated, “So then I post a lot so they [my friends] can see what I’m doing” and another mentioned that “I think about what other people want, are gonna like and what they enjoy seeing on there so that’s the kind of stuff I post.”

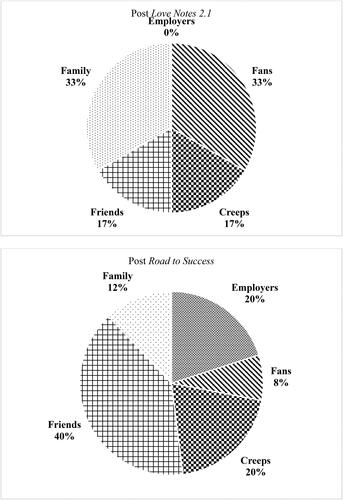

Sometimes the audiences adolescents discussed being aware of were referred to generically, such as when students mentioned that what they posted to a specific platform would depend on “who’s on there” or how “people will relate to it.” More often, however, adolescents differentiated between specific types of audiences, which in our analyses were categorized into “friends,” “family,” “fans,” “creeps,” and “potential employers.” The prevalence of mentioning these audiences in both the Post Love Notes 2.1 (i.e., Post Relationship Education) and Post Road to Success (i.e., Post Job Readiness/Financial Literacy) focus groups is displayed in . In the following sections we elaborate on each of these types of audiences and how students considered them (or not) in their online activity during the two time points captured in this investigation. Per the recommendations of Goldberg and Allen (Citation2015), we also utilize exemplary quotes from participants throughout this section to illustrate the themes and categories we identified. Of note, specific types of audiences were sometimes described as affiliated with specific social media platforms, with websites like Facebook including more family or school-based networks, and TikTok or Instagram having younger more peer-like, but also potentially more global audiences. What was shared (or not shared) was often driven by the anticipated and specific audience students expected to be viewing their posts online.

Types of audiences

Friends

The “friends” code was used when participants made statements about knowing that friends interact with their social media content and the ways they may change their posts based on how they anticipated their friends might judge or respond to the content. Some participants described sharing funny posts with the intention of entertaining their friends. Others indicated there are different settings to use on their social media platforms to ensure that only their friends see select social media content, often surrounding more personal or school-based dynamics than what might be shared more broadly with family members or the larger public. Most commonly mentioned by participants was their awareness that they expect friends to see their activity online, and sometimes they have settings for only certain friends to see their social media content. As one participant noted, “And that one’s [account] usually private and it’s usually kinda only your really close friends who are allowed to follow it” (Post Love Notes 2.1). Or as another further elaborated:

“It’s like it’s- you have your real Instagram account where you post about how cool life is and then your fake Instagram account, finsta, where people post random stuff or vent or whatever and it kinda like it’s just so they can have another out-way to talk about their actual feelings without going through their real Instagram” (Post Love Notes 2.1).

Family

The code “family” was used when participants mentioned their family members either broadly, or regarding specific family members (e.g., mom, aunt, uncle) as an audience of their social media presence. Participants often discussed “family” collectively. When specific family members were mentioned during focus groups, participants usually referred to parents, or particularly, mothers. This indicates that “family” may have mostly been a reference to adult (or minor) family members, rather than similar-age cousins, siblings, or relatives (who may be treated or conceptualized more similarly to friends). Participants discussed how they at times adjusted what they posted on their social media accounts if they knew that family members were on the same platform. Generally, participants were aware that their social media content should be “appropriate” for their parents or other family members. For example, one participant indicated,

I think in consideration of my family because I follow my family on social media and I don’t wanna post something that I won’t approve of and they won’t approve of so it’s like I can post my picture of me and my sisters and that fine but if it’s picture of mhmm [indicating something inappropriate], I can’t post it because… anyways, I don’t really wanna post it cause my family’s on here and they can see everything so you gotta be watchful. (Post Love Notes 2.1)

Another participant admitted that they blocked their mom on one platform, although they did not explain why. Other participants indicated that some of their posts that are intended for friends to see, family members will interact with instead. Participants sometimes indicated frustration when an unintended audience (such as a family member) interacted with a post that had been intended for another audience (such as their friends).

I’m kinda just like, it depends on who it is, because if I post something that I want my friends to see and then my mom comments on it and it’s just like ‘oh my God Mom…’ (Post Road to Success)

Fans

Some participants described having “fans” whom they considered an audience of their social media presence. This theme was brought up across multiple groups at both time points. It appeared that some students in focus groups either were, or were attempting to become, social influencers with large followings. Some students described spending significant time finding the correct joke or meme or practicing dance routines to new trending music that they expected to resonate with audiences on social media platforms. Such content and performances were often described as being targeted toward real or potential “fans” in addition to friends. “Fans” were described as being a distinct audience from friends or family members. We suspect this mention of “fans,” in some contexts, may have been used in a joking manner (e.g., students may have laughed or cheekily smiled accompanying their comments about “fans”). Participants did not explicitly define what “fans” were but seemed to give the impression that these were people with whom they interacted online but did not know in person (or at least, did not know well). As one participant mentioned, “All my social media. My fans love me” (Post Love Notes 2.1). Another participant indicated they wanted to be sure their fans online were updated on their life, “I gotta reach out to my fans and let them know I’m still alive” (Post Road to Success). When discussing potential “fans” students often stressed the importance of being popular, and presenting a polished persona to unknown (or only somewhat known) others:

I think for me personally, for Instagram especially, social media is kind of an outlook to see the most polished part of my life. I guess so it’s not like I’ll post any picture I take throughout the day, it’s an activity that I was a part of that I really wanna show off, not show off necessarily but put out there and the best pictures of myself versus pictures that I might not look so good in because it’s kind of just someone’s first impression of you ‘cause I know a lot of people follow social medias of people they don’t really know. So the only way they can connect with someone is through their social media, so for me, I always wanna put the best pictures out there or the most impressive things to showcase all of that at once. (Post Love Notes 2.1).

Creeps

The “creeps” code was used when participants mentioned they were aware that “creepy” people can see their social media posts or in reference to those they did not want seeing their private life or pictures. Participants discussed “creeps” as audiences of their social media with whom they generally would not like to share personal information. Participants who mentioned “creeps” also indicated specific privacy settings they used on different platforms, like limiting location information. Some participants specified men as the “creepy” folk that frequent social media, but other participants described general scenarios of concern for others finding their address or including “uncomfortable” comments on their posts. Discussion about concerns regarding creeps was almost always driven by young women in the focus groups and seemed to be less of a concern for the young men.

Um, the reason I don’t do some stuff on social media is because once you put it out there it’s always out there. So, I don’t just like, like I don’t just like be on Facebook like just posting pictures in just my bra on or like showing my booty or something like that because you never know who could be out there looking at them pictures and it’s like, like, creepy old men be on Facebook every day and just because you’re not friends with them don’t mean they can’t see your pictures. And stuff like that and yeah it just like censorship for me. (Post Love Notes 2.1)

Like say if it’s like, you tend to post things regularly, consistently and a consistent person that’s always there. Even like kind of where comments you don’t really feel comfortable about, you know some people just ignore it. Oh, three likes, it’s okay I don’t mind him and then you post something like you in front of your house. Now they have your address. Now they come, and then, it’s a nightmare. It gets like that. Or like, you have, you’re in, you have like someone you’re close to, and they use like social media against you. And then you get cyberbullied, or they threaten you in ways like that. (Post Road to Success)

Potential employers

The code “potential employers” was used when participants expressed their awareness that past, current, or future employers are on social media and can see their posts. Only after the job readiness and financial literacy intervention did participants mention knowing that employers could be watching their social media accounts, and this occurred across several focus groups. Participants mostly expressed worry over this, citing issues with being fired or not being hired because of social media activity. Some participants indicated that posts may prompt a discussion with their employer that could be unwanted by the participant. Adolescents’ awareness that their past, current, or future employers could see their social media posts may be an indication of the value they placed in having a job and an ability to self-regulate their online activity.

Your jobs can look at you, at your social media stuff. So, like, if it’s like I’m going for a job and I have to be very serious and I really want this job and I post like a pic or a video that’s not for the job, or the job doesn’t like it then they can fire me… So, you’ve got to be careful. (Post Road to Success)

Yeah, it depends on the person though, to be honest. Like if you post something in the moment and then your like employer sees it and like ‘oh why did you post this’ and now you have to explain why you posted it. ‘Why would you do this and that.’ (Post Road to Success)

Changes in awareness over the course of intervention participation

Analyses seemed to demonstrate some changes between waves, with participants reporting increased “Awareness of Audiences” that they attributed to their involvement in CARE4U. At the completion of the intervention, participants reported and appeared to have become more cognizant that potential future partners, employers, and “creepy people” were “looking up your stuff” online and could view, misuse, or disapprove of content posted on social media—resulting in potentially negative real-world effects. When assessing variations in codes, categories, and themes across the two waves of focus groups, the most salient distinction involved an awareness of current or “potential employers” as a digital audience.

Specifically, as demonstrated in , employers were never mentioned before exposure to the job readiness intervention, but after completing the intervention, references to employers were made in several groups. Importantly, participants attributed these changes in part to the conversations that had occurred within the CARE4U classrooms, with one participant explaining at the conclusion of the intervention “We had like a little small talk about like what to say and what not to say and like don’t post like anything that’s going to make you in a bad light and be in a bad light.” Though brief, these small conversations were viewed as valuable in developing their thoughtfulness about how they engaged with others through social media; a message they did not always receive, or receive consistently, from other outlets.

Discussion

The present study examined how adolescents decide to interact on social media and the impact of a comprehensive school-based intervention (one focused on healthy relationships, financial literacy, and job readiness) on their social media decisions. In this investigation, we found adolescents described their decisions about engaging and posting content on social media to be based upon who they thought would view said content and how they expected this imagined audience would react to their posts. Participants described variable approaches to social media depending on whether they expected “friends,” “creeps,” “family members,” “potential employers,” or “fans” to be the main consumers of the social media content they generated. Of note is that our analysis did not reveal that participants mentioned potential romantic partners as an audience of their social media. This is interesting because the content of Love Notes 2.1 explicitly focuses on romantic relationships.

Those adolescents who thought about their “friends” or “fans” were less likely to discuss considerations for broader audiences, which could then potentially have social or economic consequences. This finding aligns well with research on other risk-taking behaviors or tasks—like speeding, using alcohol, or gambling—that suggests adolescents are particularly prone to risky behavior when unmonitored and seeking approval from peers (Shulman et al., Citation2016). In contrast, when adolescents considered that creeps as well as potential or current employers might view their social media postings, they stressed the importance of being thoughtful about and consciously curating the information they shared on social networks. Perhaps most importantly, we saw spontaneous reference to consideration of employers only mentioned after adolescent participants had spent several months in a financial literacy and job readiness school-based intervention. We believe this finding provides some preliminary indication that broad school-based interventions may hold promise for affecting adolescents’ cognitions and behaviors when interacting in online spaces and believe this indicates a need for future testing and evaluation of such intervention with consideration for online and social media-related outcomes.

Alignment with existing theories and research

Adolescents’ consideration of sharing content online (or not) is likely impacted by who they think is available (presence), how social media sites are organized (groups), the extent to which they are interested in relating (relationships) or conversing (conversations) with others, and how they view themselves as individuals (identity), and in relation to others (reputation; Kietzmann et al., Citation2011). The nuanced understanding that adolescents have about who is viewing their social interactions may be a testament to their higher development of interpersonal competence (Selman, Citation1981), in that adolescents are aware of how different types of people may react to their online presence and adjust their online behavior accordingly. The present study’s findings that center around the core concept of “awareness of audiences” align with and provide concrete support for this notion, while also demonstrating potential ways adolescent interventions might help further scaffold adolescents in safely navigating online environments. As such, our findings indicate that adolescents are considering what their online presence says about themselves to others, and they are thinking about how different groups may impact their thoughts around posting online. These findings also cohere with Social Information Processing Theory because there is evidence that adolescents are considering their interactions with others as they decide how to present themselves (Lemerise & Arsenio, Citation2000; Walther, Citation2015). Adolescents in this study appeared to be encoding cues and acquiring rules from peers and other audiences, including their [program blinded] facilitators, as they developed a social schema for how to interact in digital spaces (Lemerise & Arsenio, Citation2000).

In line with the present study’s findings, previous research has found adolescents may primarily curate their online presence for friends, family, and acquaintances, while also purposefully crafting social media profiles for a wider public to invite new people into their lives (Yau & Reich, Citation2019). For example, adolescent Facebook users spend significant time personalizing presentations of themselves and seeking belonging (Nadkarni & Hofmann, Citation2012), which may be beneficial because social connectedness through ongoing communication or positive reinforcement has been linked to positive mental health outcomes (Grieve et al., Citation2013). Nevertheless, facilitating a sense of belonging online can pose significant challenges for adolescents; identity is an area of important development during adolescence and its shifting nature may conflict with attempts to display an image that is consistently “likeable,” “interesting,” and “attractive” (Yau & Reich, Citation2019). Our findings are consistent with these ideas, as participants frequently talked about posting to make others laugh or to get “likes.”

In line with Crick and Dodge (Citation1994) Social Information Processing Theory, students’ shift in thinking may represent a change in their schema about how social media operates and who is present on it. Before discussing the importance of and preparation for having a job and managing finances, students’ social media schemas may not have included employers (or at least, the salience of this audience was low enough that it was not brought up in a broad discussion about navigating social media posts). A broad work-skills and employment intervention may have led to a higher theorizing level, changing the cognition, motivation, affect, and selection behaviors adolescents engage in on social media. Part of this shift, evidenced in our results, may lie within their schema of audiences within digital spaces. Developing adolescents’ ability to accurately evaluate potential audiences in social media spaces may help them to understand and better prepare for transitions to and during adulthood.

Implications for practitioners

This study has implications for several fields, including education, psychology, human development, sociology, and others. Our finding that after a job readiness and financial literacy school-based curriculum (Road to Success), adolescents spontaneously considered how past, current, and future employers may have access to their social media accounts and posts addresses an important aspect of life skills education. School-based interventions could be further tailored to assist in providing such education, and school psychologists, counselors, and educators may be important agents in promoting, enacting, and advocating for this type of curricula.

The way that adolescents must get and keep a job now involves awareness of online activity, including who can see what adolescents are doing online. Job readiness interventions may prevent adolescents from making “mistakes” online that impact their future. Classroom settings where related topics are discussed (e.g., health and life skills classes) are likely appropriate for integrating information about online behavior and its impact (e.g., employment). It may be possible to create dedicated lessons on these issues, or to incorporate them as brief sub-topics into discussions about other related topics (safety, healthy relationships, interviewing). Comprehensive employment interventions have been shown to reduce problem behaviors in a wide variety of areas including reduced involvement in violent crimes (Modestino, Citation2019), greater financial success, higher academic achievement and improved school attendance, and increased likelihood for attending college (Leos-Urbel, 2014; Starobin et al., Citation2013).

Based on our findings, we propose it is possible these positive benefits may also extend to digital environments. School personnel may directly instruct adolescents about appropriate posts, privacy settings, and other personalization steps that minimize the risk of not being hired or losing a job. Just as enhancing traditional soft skills may increase confidence in work performance (Ritter et al., Citation2018), including lessons on social media activity and how that activity relates to employment may help those entering the workforce (e.g., adolescents) feel more prepared. Additionally, this study complements previous psychological evidence regarding how students’ awareness of audiences may influence their posts on social media (Wolf et al., Citation2015; Zheng et al., Citation2019). From the extant literature, personality factors, temperament, mental health indicators, brain development, and related concepts may hold promise in providing a more comprehensive understanding of how social media behavior varies between adolescents, and how perceptions and awareness of different audiences may impact risk-taking online (Branley & Covey, Citation2018;; D’Agata & Kwantes, Citation2020). These factors may also be explored as components of adolescent programs that discuss social media activity, and the interconnectedness of these factors may also in part explain why we saw shifts in social media behavior despite the broader focus of the intervention provided (Flay, Citation2003).

Limitations and future directions

It is important to consider these findings within the context of the study’s limitations. Because of the context of these focus groups (within the evaluation of a larger program, occurring during a single course period during the school day), there was limited time to probe in-depth some of the issues raised by participants. For example, examining what terms like “fans” may actually convey would provide a richer context to how adolescents discuss social media. Future researchers may consider focusing on how different identities, or different aspects of the framework proposed by Kietzmann et al. (Citation2011) are involved in adolescents’ social media use. To further investigate adolescents’ perceptions of others on social media, future research may expand interview questions, allowing for more in-depth information. Another direction for future research could involve developing and implementing quantitative measures of the extent to which adolescents consider various online audiences to evaluate statistical associations with online behaviors, or to test the effectiveness of interventions through experimental procedures. Second, this sample only represents one region in the Midwest. To generalize these results, adolescents from several geographic and cultural contexts may provide a more complete overview of perceived audiences on social media. Though the sample in this study was diverse and reflects an often-underrepresented population of students, one possibility would be to utilize individual interviews to explore how individual differences influence perceived audiences on social media to inform more wide-ranging interventions.

Conclusion

Equipping adolescents with skills and knowledge that are necessary for navigating an increasingly digital world has become an important albeit challenging task for adults and parents (Ahn, Citation2011; Anderson & Jiang, Citation2018; Bányai et al., Citation2017; van Dijck, Citation2013). Comprehensive school-based interventions may serve as an effective tool that can be utilized to develop responsibility more generally (Taylor et al., Citation2017), as well as specific awareness about online risks and behaviors. Our findings suggest that speaking to students about the audiences of their social media activity may resonate within their decision finding schema for interacting online and allow them to develop a more sophisticated cognitive model of the variable and long-term potential consequences of online behavior.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ahn, J. (2011). The effect of social network sites on adolescents’ social and academic development: Current theories and controversies. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 62(8), 1435–1445. doi:10.1002/asi.21540

- Anderson, M., & Jiang, J. (2018). Teens, social media & technology 2018. Pew Research Center, 31, 2018. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2018/05/31/teens-social-media-technology-2018/

- Baccarella, C. V., Wagner, T. F., Kietzmann, J. H., & McCarthy, I. P. (2018). Social media? It’s serious! Understanding the dark side of social media. European Management Journal, 36(4), 431–438. doi:10.1016/j.emj.2018.07.002

- Bányai, F., Zsila, Á., Király, O., Maraz, A., Elekes, Z., Griffiths, M. D., … Demetrovics, Z. (2017). Problematic social media use: Results from a large-scale nationally representative adolescent sample. PloS One, 12(1), e0169839. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0169839

- Branley, D. B., & Covey, J. (2018). Risky behavior via social media: The role of reasoned and social reactive pathways. Computers in Human Behavior, 78, 183–191. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2017.09.036

- Cohen, A. O., Breiner, K., Steinberg, L., Bonnie, R. J., Scott, E. S., Taylor-Thompson, K., … Casey, B. J. (2016). When is an adolescent an adult? Assessing cognitive control in emotional and nonemotional contexts. Psychological Science, 27(4), 549–562. doi:10.1177/0956797617690343

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2015). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. SAGE.

- Crick, N. R., & Dodge, K. A. (1994). A review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in children’s social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin, 115(1), 74–101. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.115.1.74

- Curran, T., & Wexler, L. (2017). School-based positive youth development: A systematic review of the literature. The Journal of School Health, 87(1), 71–80. doi:10.1111/josh.12467

- D’Agata, M. T., & Kwantes, P. J. (2020). Personality factors predicting disinhibited and risky online behaviors. Journal of Individual Differences, 41(4), 199–206. doi:10.1027/1614-0001/a000321

- Drouin, M., O’Connor, K. W., Schmidt, G. B., & Miller, D. A. (2015). Facebook fired: Legal perspectives and young adults’ opinions on the use of social media in hiring and firing decisions. Computers in Human Behavior, 46, 123–128. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.01.011

- Flay, B. R. (2003). Positive youth development is necessary and possible. In D. Romer (Ed.), Reducing adolescent risk: Toward an integrated approach (pp. 347–354). SAGE.

- Goldberg, A. E., & Allen, K. R. (2015). Communicating qualitative research: Some practical guideposts for scholars. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77(1), 3–22. doi:10.1111/jomf.12153

- Grieve, R., Indian, M., Witteveen, K., Tolan, G. A., & Marrington, J. (2013). Face-to-face or Facebook: Can social connectedness be derived online? Computers in Human Behavior, 29(3), 604–609. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2012.11.017

- Hidy, K., & McDonald, M. S. (2013). Risky business: The legal implications of social media’s increasing role in employment decisions. Journal of Legal Studies in Business, 18, 69–88. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3188753

- Kietzmann, J. H., Hermkens, K., McCarthy, I. P., & Silvestre, B. S. (2011). Social media? Get serious! Understanding the functional building blocks of social media. Business Horizons, 54(3), 241–251. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2011.01.005

- Lemerise, E. A., & Arsenio, W. F. (2000). An integrated model of emotion processes and cognition in social information processing. Child Development, 71(1), 107–118. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00124

- Leos‐Urbel, J. (2014). What is a summer job worth? The impact of summer youth employment on academic outcomes. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 33(4), 891–911. doi:10.1002/pam.2178

- Lub, V. (2015). Validity in qualitative evaluation: Linking purposes, paradigms, and perspectives. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 14(5), 160940691562140. doi:10.1177/1609406915621406

- Marwick, A. E., & Boyd, D. (2014). Networked privacy: How teenagers negotiate context in social media. New Media & Society, 16(7), 1051–1067. doi:10.1177/1461444814543995

- Matsakis, L. (2019). The WIRED guide to your personal data (and who is using it). Wired. https://www.wired.com/story/wired-guide-personal-data-collection/

- Modestino, A. S. (2019). How do summer youth employment programs improve criminal justice outcomes, and for whom? Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 38(3), 600–628. doi:10.1002/pam.22138

- Moreno, M. A., Briner, L. R., Williams, A., Brockman, L., Walker, L., & Christakis, D. A. (2010). A content analysis of displayed alcohol references on a social networking web site. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 47(2), 168–175. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.01.001

- Nadkarni, A., & Hofmann, S. G. (2012). Why do people use Facebook? Personality and Individual Differences, 52(3), 243–249. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2011.11.007

- O’Reilly, M., Dogra, N., Whiteman, N., Hughes, J., Eruyar, S., & Reilly, P. (2018). Is social media bad for mental health and wellbeing? Exploring the perspectives of adolescents. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 23(4), 601–613. doi:10.1177/1359104518775154

- Patchin, J. W., & Hinduja, S. (2020). Sextortion among adolescents: Results from a national survey of U.S. youth. Sexual Abuse : A Journal of Research and Treatment, 32(1), 30–54. doi:10.1177/1079063218800469

- Pearson, M. (2016). Love notes. The Dibble Institute for Marriage Education. https://www.dibbleinstitute.org/our-programs/love-notes/

- Ritter, B. A., Small, E. E., Mortimer, J. W., & Doll, J. L. (2018). Designing management curriculum for workplace readiness: Developing students’ soft skills. Journal of Management Education, 42(1), 80–103. doi:10.1177/1052562917703679

- Romer, D., Betancourt, L. M., Brodsky, N. L., Giannetta, J. M., Yang, W., & Hurt, H. (2011). Does adolescent risk taking imply weak executive function? A prospective study of relations between working memory performance, impulsivity, and risk taking in early adolescence. Developmental Science, 14(5), 1119–1133. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7687.2011.0106.x

- Salter, M. (2016). Privates in the online public: Sex(ting) and reputation on social media. New Media & Society, 18(11), 2723–2739. doi:10.1177/1461444815604133

- Santrock, J. (2018). Adolescence (17th edition). McGraw-Hill Education.

- Selman, R. L. (1981). The development of interpersonal competence: The role of understanding in conduct. Developmental Review, 1(4), 401–422. doi:10.1016/0273-2297(81)90034-4

- Shulman, E. P., Smith, A. R., Silva, K., Icenogle, G., Duell, N., Chein, J., & Steinberg, L. (2016). The dual systems model: Review, reappraisal, and reaffirmation. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 17, 103–117. doi:10.1016/j.dcn.2015.12.010

- Starobin, S. S., Hagedorn, L. S., Purnamasari, A., & Chen, Y. A. (2013). Examining financial literacy among transfer and nontransfer students: Predicting financial well-being and academic success at a four-year university. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 37(3), 216–225. doi:10.1080/10668926.2013.740388

- Taylor, R. D., Oberle, E., Durlak, J. A., & Weissberg, R. P. (2017). Promoting positive youth development through school-based social and emotional learning interventions: A meta-analysis of follow-up effects. Child Development, 88(4), 1156–1171. doi:10.1111/cdev.12864

- van Dijck, J. (2013). The culture of connectivity: A critical history of social media. Oxford University Press.

- Walther, J. B. (2015). Social information processing theory: Impressions and relationship development online. In D. O. Braithwaite and P. Schrodt (Eds.) Engaging theories in interpersonal communication: Multiple perspectives (2nd edition). pp. 417–428 Sage.

- Wolf, L. K., Bazargani, N., Kilford, E. J., Dumontheil, I., & Blakemore, S. J. (2015). The audience effect in adolescence depends on who’s looking over your shoulder. Journal of Adolescence, 43(1), 5–14. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.05.003

- Yang, C. C., Holden, S. M., Carter, M. D., & Webb, J. J. (2018). Social media social comparison and identity distress at the college transition: A dual-path model. Journal of Adolescence, 69(1), 92–102. doi:10.1007/s10964-017-0801-6

- Yau, J. C., & Reich, S. M. (2019). “It’s just a lot of work”: Adolescents’ self‐presentation norms and practices on Facebook and Instagram. Journal of Research on, 29(1), 196–209. doi:10.1111/jora.12376

- Zheng, D., Ni, X. L., & Luo, Y. J. (2019). Selfie posting on social networking sites and female adolescents’ self-objectification: The moderating role of imaginary audience ideation. Sex Roles, 80(5-6), 325–331. doi:10.1007/s11199-018-0937-1

Appendix a

Final Coding Scheme for Social Media Topics

Social Media

Self-Oriented Feelings/Associations: When a participant expresses their thoughts and feelings about social media come from their own actions on social media

Negative Self-Oriented Feelings/Associations: When a participant expresses their negative thoughts and feelings about social media come from their own actions on social media

Positive Self-Oriented Feelings/Associations: When a participant expresses their positive thoughts and feelings about social media come from their own actions on social media

Other-Oriented Feelings/Associations: When a participant expresses their thoughts and feelings about social media come from others’ actions on social media

Negative Other-Oriented Feelings/Associations: When a participant expresses their negative thoughts and feelings about social media come from others’ actions on social media

Positive Other-Oriented Feelings/Associations: When a participant expresses their positive thoughts and feelings about social media come from others’ actions on social media

Purpose: When a participant expresses a purpose for using social media

Information gathering: When a participant expresses that the/one purpose for using social media is to gather information

Broadcasting: When a participant expresses that the/one purpose for using social media is to broadcast information about themselves, events, etc.

Entertainment: When a participant expresses that the/one purpose for using social media is to be entertained

Social connection: When a participant expresses that the/one purpose for using social media is to facilitate a social connection (e.g., stay in-touch with friends and family)

Communication: When a participant expresses that the/one purpose for using social media is to communicate (e.g., a participant says they use direct messages to “talk” with others)

Frequency: When a participant expresses the frequency of which they use social media

Never: When a participant says they do not use social media

Sometimes: When a participant says they use social media sometimes, “a little,” “not so much,” etc.

Often: When a participant says they use social media often, “a lot,” “frequently,” etc.

Platform: When a participant indicates a social media platform they use (e.g., Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat)

Awareness of Audience: When a participant expresses they know others are on social media and can see what they post

Family: When a participant expresses they know their family is on social media and can see what they post

Friends: When a participant expresses they know their friends are on social media and can see what they post

Fans: When a participant expresses they have fans on social media and can see what they post

Creeps: When a participant expresses they know there are creepy people on social media and can see what they post

Employers: When a participant expresses they know employers are on social media and can see what they post

Self-Presentation: When a participant expresses they care about their self-presentation on social media

Editing photos: When a participant expresses they edit their photos to personalize their self-presentation on social media

What to share: When a participant expresses they consider their self-presentation before deciding what to post on social media

Social Comparison: When a participant expresses they compare themselves to others on social media

Social Media Influences: things (people, factors, systems, etc.) that influence the way in which participants interact on social media. This include what causes them to post or not post something, why they share what they share, and what influences their use of certain social media platforms.

Impact of [Program]: when participants mention how [Program] has addressed their social media usage

Increased Awareness: When participants express [Program] has increased their awareness about using social media

No Impact of [Program]: when participants indicate [Program] has had no influence on their social media usage.