Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is one of the leading causes of mortality around the world. COPD is characterised by a heterogeneous clinical presentation and prognosis which may vary according to the clinical phenotype. One of the phenotypes of COPD most frequently studied is the asthma-COPD overlap (ACO), however, there are no universally accepted diagnostic criteria for ACO. It is recognised that the term ACO includes patients with clinical features of both asthma and COPD, such as more intense eosinophilic bronchial inflammation, more severe respiratory symptoms and more frequent exacerbations, but in contrast, it is associated with a better prognosis compared to COPD. More importantly, ACO patients show better response to inhaled corticosteroid treatment than other COPD phenotypes. The diagnosis of ACO can be difficult in clinical practice, and the identification of these patients can be a challenge for non-specialized physicians. We describe how to recognise and diagnose ACO based on a recently proposed Spanish algorithm and by the analysis of three clinical cases of patients with COPD. The diagnosis of ACO is based on the diagnosis of COPD (chronic airflow obstruction in an adult with significant smoking exposure), in addition to a current diagnosis of asthma and/or signficant eosinophilia.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a heterogeneous disease with a clinical presentation and prognosis which may vary according to the clinical phenotype (Citation1). In the last years, one of the phenotypes of COPD, the so-called asthma-COPD overlap (ACO), has received increasing attention. The term ACO has been applied to patients who present clinical features of both asthma and COPD (Citation2).

In contrast to other COPD phenotypes, patients with ACO more frequently present a greater degree of eosinophilic bronchial inflammation, which translates into a greater response to inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) treatment (Citation3–5). This characteristic can be explained in a significant number of ACO patients by a history of asthma during youth, which, in turn, is an independent risk factor for the development of chronic airflow obstruction (i.e. COPD) in smokers (Citation6). From a clinical point of view, patients with ACO are usually more symptomatic and have a worse quality of life and a higher risk of exacerbations than other COPD patients (Citation7–9), but in contrast, they have a better survival (Citation10, Citation11).

In the last years there have been attempts to define the diagnostic criteria of this phenotype, but no definitive consensus has yet been achieved. In Spain, a diagnostic consensus was initially proposed with very restrictive criteria, in which 2 major criteria or 1 major and 2 minor had to be fulfilled for a patient to be defined as ACO. The major criteria included a very positive bronchodilator test (BDT) (increase in forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1) of ≥400 mL and 15% compared to baseline), eosinophilia in sputum and a personal history of asthma before the age of 40; while the minor criteria were an elevated total IgE, a history of atopy and a positive BDT (≥200 mL and 12% increase in FEV1) on at least two occasions (Citation12). These diagnostic criteria have been adopted with minimal modifications by other national COPD guidelines, such as the Finnish and the Czech (Citation13, Citation14). Thereafter, a joint document between the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) and the Global initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) defined ACO as persistent airflow obstruction with characteristics of both asthma and COPD, but did not clearly specify how many criteria should be met to establish a diagnosis of ACO (Citation15). Moreover, the committee weighed each criterion equally.

Later, in 2016, an international consensus was developed by a group of specialists in North America, Europe and Asia, who proposed 3 major criteria (persistent airflow obstruction in patients over 40 years of age, exposure to smoking of at least 10 pack-years or the equivalent in biomass smoke exposure, a documented history of asthma before age 40 or an increase after BDT > 400 mL in FEV1 and 3 minor criteria (documented history of atopy or allergic rhinitis, BDT ≥200 mL and 12% increase in FEV1 on at least 2 occasions and peripheral eosinophilia ≥300 eosinophils/µL). For a diagnosis of ACO, 3 major criteria and at least one of the minor criteria proposed had to be met (Citation16).

More recently, the new consensus between the Spanish COPD guidelines (GesEPOC) and the Spanish guidelines for asthma (GEMA) has simplified the definition of ACO, and it is now defined as the presence of chronic persistent airflow obstruction in a smoker or ex-smoker [exposure factor (EF) ≥10 pack-years] older than 35 years with a concomitant diagnosis of asthma or with one of the following characteristics: very positive BDT (≥15% and ≥400 mL increase in FEV1) and/or blood eosinophilia (≥300 eosinophils/µL). Thus, the ACO phenotype includes not only smoking asthmatics with persistent airflow obstruction, but also COPD patients with asthma-like features, such as increased reversibility and/or eosinophilic inflammation. To fulfil this definition, airflow obstruction must be persistent over time, current or past smoking should be the main risk factor, and the patient must present clinical, biological or functional characteristics of asthma (Citation17). Of note, GesEPOC recommends the use of the lower limit of normal of the FEV1/FVC to identify airflow obstruction in individuals younger than 50 and older than 70 years to avoid misdiagnosis. These different consensus criteria proposed are summarised in .

Table 1. The different criteria proposed for the diagnosis of ACO in different consensus and guidelines.

Due to the lack of universally accepted diagnostic criteria, the diagnosis of ACO in clinical practice is a daily challenge for physicians (Citation18). Here, we present three clinical cases in order to analyse their clinical presentations and the different criteria proposed by the Spanish consensus.

Clinical cases

History of asthma

This was a 50-year-old male, former smoker with tobacco exposure of 30 pack-years, intolerant to aspirin and pharmacologic allergy to penicillin. Diagnosed with asthma at the age of 18 after two episodes of bronchospasm. He received a long-acting beta agonist (LABA) bronchodilator and ICS treatment for two years that was discontinued afterwards. Posteriorly, at the age of 48 he was hospitalised for an asthma exacerbation that was treated with bronchodilators, ICS and oral corticosteroids (OCS). Following hospitalisation, he was referred to our centre to continue study and treatment. Lung function tests showed moderate airflow obstruction: FVC (forced vital capacity) 3.95 L (66.8%), FEV1 2.41L (52.8%), FEV1/FVC 61% with a negative bronchodilator test and severely decreased diffusing lung capacity of carbon monoxide (DLCO of 31%). In addition, paraseptal emphysema was observed in the thoracic computerised tomography (CT), and a blood analysis showed 210 eosinophils/μL (2.2%). With this presentation, the patient was diagnosed with COPD with an ACO phenotype because of his well-documented history of asthma. Triple therapy (LABA, LAMA (long-acting muscarinic antagonist) and ICS) was initiated, and after three months of follow-up, the patient showed clinical improvement without exacerbations.

Bronchodilator responsiveness

This was a 58 year-old male, former heavy smoker with tobacco exposure of 54 pack-years. He had a history of atopy and allergic rhinitis since youth and was hospitalised at the age of 56 due to dyspnoea and wheezing. During hospitalisation, a thoracic CT scan was performed showing bilateral centrilobular emphysema predominantly in the upper lobes. In addition, a lung function test after discharge showed severe airflow obstruction: FVC 2.64 (59%), FEV1 1.39L (31%), FEV1/FVC 52.6% with a positive BDT (increase of 410 mL and 41.8%). Blood analysis showed 500 eosinophils/μl (7.9%). He was then diagnosed with COPD with an ACO phenotype due to the very positive BDT, although he also fulfilled the criterion of blood eosinophils > 300 cells/μL. The patient initiated triple therapy (LABA/LAMA/ICS), showing clinical improvement.

High blood eosinophilia

This was a 73 year-old male, former smoker with tobacco exposure of 60 pack-years. Since the age of 67 years he referred having at least two exacerbations per year with audible wheezing requiring systemic corticosteroids and antibiotics. Lung function tests showed severe airflow obstruction (FVC 2.40L (59.6%), FEV1 1.13L (40%), FEV1/FVC 47%) with a negative BDT. The blood test showed high eosinophils (340 cells/μL, 5.7%), and diffuse centrilobular emphysema was observed in the thoracic CT scan. The patient was diagnosed with COPD with an ACO phenotype due to the high blood eosinophil count, and triple therapy was initiated, presenting clinical improvement.

Discussion

The identification of ACO in COPD is relevant because these patients will benefit from the early introduction of treatment with ICS. Although COPD and asthma have unique and differential characteristics, some patients may share aspects of both diseases. The difficulties in the differential diagnosis of asthma and COPD may increase with the addition of this third group of patients with ACO (Citation18–20). Different scientific societies and expert groups have proposed criteria for the diagnosis of ACO (), and large observational studies have used different criteria to diagnose ACO (). Here, three clinical cases are described to illustrate the application of the recent Spanish criteria included in the Spanish guidelines for the management of asthma or COPD (Citation17).

Table 2. Different diagnostic criteria of ACO used in clinical observational studies.

Previous history of asthma

The first step to diagnose ACO should be a confirmed diagnosis of COPD based on smoking (or equivalent noxious exposure), respiratory symptoms and non-fully reversible airflow obstruction. Subsequently, the diagnosis of asthma should be confirmed by a well-documented history of asthma and/or a current diagnosis of asthma according to guidelines (Citation21). If the diagnosis of asthma cannot be established, the diagnosis of ACO can be confirmed by the presence of a very positive BDT (increase of ≥400 mL and 15% in FEV1 compared to baseline) and/or the presence of blood eosinophilia (≥300 cells/µL) as a surrogate marker of airway eosinophilia (Citation22).

In a recent study performed by Barrecheguren et al. (Citation23), the authors observed that a previous history of asthma before the age of 40 used as a single criterion to diagnose ACO in a population of patients with COPD identified a group of individuals with similar characteristics to those identified as ACO using the more restrictive criteria of the first Spanish consensus of ACO (Citation12). Moreover, in the ECLIPSE study, the addition of other asthma features, such as bronchodilator responsiveness, the presence of atopy or respiratory symptoms, to the previous history of asthma did not add value to the diagnosis of ACO in patients with COPD (Citation24).

In the new Spanish COPD guidelines, a history of asthma in a patient with COPD constitutes, by itself, a diagnostic criterion of ACO (Citation25); however, it is important to highlight that significant smoking exposure is necessary for the diagnosis of COPD, and therefore, of ACO. Otherwise, in the absence of significant smoking exposure, the patient should be diagnosed with chronic, irreversible asthma but not ACO. Differences between ACO and irreversible asthma were evaluated by Tommola et al. (Citation26), and no differences were found in terms of the prevalence of rhinitis, atopy or allergy between patients with ACO and non-smoking asthmatics with irreversible airway obstruction. However, a worse diffusion capacity, higher blood neutrophil counts and higher interleukin (IL)-6 concentrations were found in patients with ACO compared with irreversible asthmatics. Therefore, significant smoking exposure is necessary to differentiate chronic irreversible asthma from ACO. In any case, this differentiation has no practical consequences since in both, ACO and chronic irreversible asthma, the treatment is the same and is based on the combination of long-acting bronchodilators and ICS, with triple therapy in the most severe cases.

In our case, the patient had a well-established COPD and a previous diagnosis of asthma, and the key feature to differentiate ACO from chronic irreversible asthma was tobacco exposure of 30 pack-years.

Very positive bronchodilator test

Increased reversibility is included as a criterion for ACO in most consensus statements based on some evidence that suggests that these individuals are a particular type of COPD patients with different clinical characteristics that simulate asthma (Citation27) and have a better long term prognosis compared with irreversible COPD (Citation28). However, as indicated by Pascoe et al. (Citation3), having a positive BDT (i.e. increase in FEV1 of at least 200 mL and 12%) is a very frequent finding in COPD and is not a valid marker for response to ICS in COPD. For example, in the UPLIFT study, performed in COPD patients without a previous diagnosis of asthma, up to 54% of the 5756 patients included had a positive BDT (Citation29). In addition, a positive or negative status in BDT can quite often change, suggesting that a positive BDT may not be a stable phenotype (Citation30). For all these reasons, a positive BDT should not be considered a criterion for ACO (Citation31). However, a very positive BDT, defined as an increase in FEV1 of at least 400 mL and 15% may identify a particular population of COPD patients with different characteristics (Citation27, Citation28). This threshold of 400 mL in FEV1 was defined by the National Institute for Care and Health Excellence (NICE) as being suggestive of asthma or an asthmatic component of COPD (Citation32). In fact, in one of the first definitions of ACO, Gibson and Simpson included a 400 mL increase in FEV1 as one of the diagnostic criteria (Citation33). This is supported by the relationship found between highly increased reversibility to airflow in COPD and response to ICS in terms of lung function (Citation34–36), probably related to the linear association between increased reversibility and eosinophilic inflammation in COPD (Citation37, Citation38).

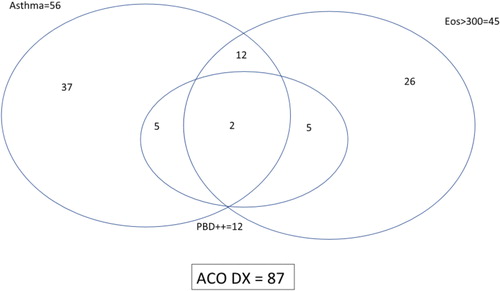

Despite the possible association of high reversibility and response to ICS and ACO, this criterion may not be useful in clinical practice, since very few patients with COPD show this increased reversibility. In the ECLIPSE study only 5% of patients had a reversibility > 400 mL (Citation24) similarly to the results of the ISOLDE trial (Citation30), and probably most highly reversible patients also have some degree of eosinophilic inflammation (Citation37, Citation38, Citation39). More recently, in the study conducted by Pérez de Llano et al. (Citation40), only 12 patients (13.8%) out of 87 with a diagnosis of ACO showed very positive bronchodilator response, and almost all fulfilled other criteria for ACO (). Similarly, our patient also presented asthma-like symptoms and high blood eosinophils, which led to a definitive diagnosis of ACO, irrespective of (or in addition to) the very positive BDT.

Figure 1. Nonproportional Venn diagram showing the interrelationship of ACO criteria in a population of 292 patients with chronic obstructive airways disease. Asthma means “current diagnosis” of the disease; ++ means “very positive” bronchodilator test. Reproduced with permission from Sociedad Española de Neumología y Cirugía Torácica (SEPAR) from Pérez de Llano et al. (Citation40)

High blood eosinophilia

Another criterion proposed by the Spanish consensus and many other documents is high blood eosinophilia (≥300 eosinophils/µL) (Citation22). It has been shown that an increased eosinophil count in COPD patients is a reliable marker of an underlying Th2 type of inflammation. Christenson et al. (Citation41), observed that an increased eosinophil count in COPD patients was a marker of the Th2 genetic signature and was associated with asthma-related characteristics, such as increased bronchodilator responsiveness, and more importantly, a favourable ICS response. Recently, Cosío et al. (Citation42) conducted a study in a heterogeneous group of individuals with different types of chronic obstructive airways disease, using elevated blood eosinophilia as a marker of Th2 inflammation. They found that the classification based upon the inflammatory profile provided the best distinction of patients with chronic airways disease. However, the cut-off value for blood eosinophils to identify ACO is still controversial, although studies comparing eosinophilic inflammation in blood and sputum have suggested that a cut-off value of ≥300 eosinophils/µL in blood is a good predictor of eosinophilia in sputum (Citation43), and therefore, different consensus recommend this cut-off in peripheral blood to identify ACO (Citation16, Citation22).

It is increasingly recognised that the current definition of ACO may include different phenotypes, both Th2 and non-Th2, or in other words, patients with increased blood eosinophilia and a clinical history of asthma without marked eosinophilia (Citation44). These two phenotypes may have clinical and biological differences but have good response to treatment with ICS in common (Citation45), and therefore, from a clinical point of view, it is justified to group them together under the umbrella term of ACO.

In conclusion, diagnosing ACO is still a clinical challenge partly due to the lack of universally accepted diagnostic criteria. The new Spanish consensus that includes eosinophilic COPD and patients with COPD and a concomitant diagnosis of asthma should facilitate the recognition of ACO in the population of patients with COPD and help in the decision to use ICS in the context of the pharmacological management of COPD.

Declaration of interest

Marc Miravitlles has received speaker or consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Bial, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Cipla, CSL Behring, Laboratorios Esteve, GebroPharma, GlaxoSmithKline, Grifols, Menarini, Mereo Biopharma, Novartis, pH Pharma, Rovi, TEVA, Verona Pharma and Zambon, and research grants from GlaxoSmithKline and Grifols, unrelated to this manuscript. Miriam Barrecheguren has received speaker fees from Grifols, Menarini, CSL Behring, GSK and consulting fees from GSK, Novartis and GebroPharma. Cristina Esquinas has received speaker fees from CSL Behring. The rest of the authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Decramer M, Janssens W, Miravitlles M. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet. 2012;379(9823):1341–1351.

- Barrecheguren M, Esquinas C, Miravitlles M. The asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap syndrome (ACOS): opportunities and challenges. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2015;21:74–79.

- Pascoe S, Locantore N, Dransfield MT, Barnes NC, Pavord ID. Blood eosinophil counts, exacerbations, and response to the addition of inhaled fluticasone furoate to vilanterol in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a secondary analysis of data from two parallel randomised controlled trials. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3(6):435–442.

- Kitaguchi Y, Komatsu Y, Fujimoto K, Hanaoka M, Kubo K. Sputum eosinophilia can predict responsiveness to inhaled corticosteroid treatment in patients with overlap syndrome of COPD and asthma. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2012;7:283–289.

- Louie S, Zeki AA, Schivo M, Chan AL, Yoneda KY, Avdalovic M, Morrissey BM, Albertson TE. The asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap syndrome: pharmacotherapeutic considerations. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2013;6(2):197–219. doi:10.1586/ecp.13.2.

- Hayden LP, Cho MH, Raby BA, Beaty TH, Silverman EK, Hersh CP; COPDGene Investigators. Childhood asthma is associated with COPD and known asthma variants in COPDGene: a genome-wide association study. Respir Res. 2018;19(1):209.

- Hardin M, Silverman EK, Barr RG, Hansel NN, Schroeder JD, Make BJ, Crapo JD, Hersh CP; COPDGene Investigators. The clinical features of the overlap between COPD and asthma. Respir Res. 2011;12:127.

- Miravitlles M, Soriano JB, Ancochea J, Muñoz L, Duran-Tauleria E, Sanchez G, Sobradillo V, García-Rio F. Characterisation of the overlap COPD-asthma phenotype. Focus on physical activity and health status. Respir Med. 2013;107(7):1053–1060. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2013.03.007.

- Menezes AM, de Oca MM, Perez-Padilla R, Nadeau G, Wehrmeister FC, Lopez-Varela MV, Muiño A, Jardim JRB, Valdivia G, Tálamo C. Increased risk of exacerbation and hospitalization in subjects with an overlap phenotype: COPD-asthma. Chest. 2014;145:297–304.

- Cosio BG, Soriano JB, López-Campos JL, Calle-Rubio M, Soler-Cataluña JJ, de-Torres JP, Marín JM, Martínez-Gonzalez C, de Lucas P, Mir I, et al. Defining the Asthma-COPD Overlap Syndrome in a COPD Cohort. Chest. 2016;149:45–52.

- Suzuki M, Makita H, Konno S, Shimizu K, Kimura H, Kimura H, Nishimura M; Hokkaido COPD Cohort Study Investigators. Asthma-like features and clinical course of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. An analysis from the Hokkaido COPD Cohort Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194(11):1358–1365 doi:10.1164/rccm.201602-0353OC.

- Soler-Cataluna JJ, Cosío B, Izquierdo JL, López-Campos JL, Marín JM, Agüero R, Baloira A, Carrizo S, Esteban C, Galdiz JB, et al. Consensus document on the overlap phenotype COPD-asthma in COPD. Arch Bronconeumol. 2012;48(9):331–337 doi:10.1016/j.arbr.2012.06.017.

- Kankaanranta H, Harju T, Kilpeläinen M, Mazur W, Lehto JT, Katajisto M, Peisa T, Meinander T, Lehtimäki L. Diagnosis and pharmacotherapy of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the Finnish guidelines. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2015;116(4):291–307 doi:10.1111/bcpt.12366.

- Koblizek V, Chlumsky J, Zindr V, Neumannova K, Zatloukal J, Zak J, Sedlak V, Kocianova J, Zatloukal J, Hejduk K, et al. Czech Pneumological and Phthisiological Society Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: official diagnosis and treatment guidelines of the Czech Pneumological and Phthisiological Society; a novel phenotypic approach to COPD with patient-oriented care. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2013;157(2):189–201. doi:10.5507/bp.2013.039.

- GINA and Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) [webpage on the Internet]. Asthma, COPD, and asthma-COPD overlap syndrome. GINA and Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; 2015. Available from: http://www.goldcopd.org/asthma-copd-overlap.html. Accessed January 10, 2019.

- Sin DD, Miravitlles M, Mannino DM, Soriano JB, Price D, Celli BR, Leung JM, Nakano Y, Park HY, Wark PA, et al. What is asthma-COPD overlap syndrome? Towards a consensus definition from a round table discussion. Eur Respir J. 2016;48(3):664–673. doi:10.1183/13993003.00436-2016.

- Plaza V, Álvarez F, Calle M, Casanova C, Cosío BG, López-Viña A, Pérez de Llano L, Quirce S, Román-Rodríguez M, Soler-Cataluña JJ, et al. Consensus on the Asthma-COPD Overlap Syndrome (ACOS) Between the Spanish COPD Guidelines (GesEPOC) and the Spanish Guidelines on the Management of Asthma (GEMA). Arch Bronconeumol. 2017;53(8):443–449. doi:10.1016/j.arbres.2017.04.002.

- García-García MC, Hernández-Borge J, Barrecheguren M, Miravitlles M. The challenge of diagnosing a mixed asthma-COPD (ACOS) phenotype in clinical practice. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2016;10:175–178. doi:10.1177/1753465816630209.

- Anzueto A, Miravitlles M. Considerations for the correct diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and its management with bronchodilators. Chest. 2018;154:242–248. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2018.02.023.

- Barrecheguren M, Esquinas C, Miravitlles M. How can we identify patients with asthma-COPD overlap syndrome in clinical practice? Arch Bronconeumol. 2016;52:59–60.

- [GEMA (4.0). Guidelines for Asthma Management]. Arch Bronconeumol. 2015;51(Suppl 1):2–54.

- Miravitlles M, Alvarez-Gutierrez FJ, Calle M, Casanova C, Cosio BG, López-Viña A, Pérez de Llano L, Quirce S, Roman-Rodríguez M, Soler-Cataluña JJ, et al. Algorithm for identification of asthma-COPD overlap: consensus between the Spanish COPD and asthma guidelines. Eur Respir J. 2017;49(5):1700068. doi:10.1183/13993003.00068-2017.

- Barrecheguren M, Román-Rodríguez M, Miravitlles M. Is a previous diagnosis of asthma a reliable criterion for asthma–COPD overlap syndrome in a patient with COPD? Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:1745–1752.

- Wurst KE, Rheault TR, Edwards L, Tal-Singer R, Agusti A, Vestbo J. A comparison of COPD patients with and without ACOS in the ECLIPSE study. Eur Respir J. 2016;47(5):1559–1562.

- Miravitlles M, Soler-Cataluña JJ, Calle M, Molina J, Almagro P, Quintano JA, Trigueros JA, Cosío BG, Casanova C, Riesco JA, et al. Spanish COPD guidelines (GesEPOC) 2017. Pharmacological treatment of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Bronconeumol. 2017;53:324–335. doi:10.1016/j.arbres.2017.03.018.

- Tommola M, Ilmarinen P, Tuomisto LE, Lehtimäki L, Haanpää J, Niemelä O, Kankaanranta H. Differences between asthma–COPD overlap syndrome and adult-onset asthma. Eur Respir J. 2017;49(5):1602383. doi:10.1183/13993003.02383-2016.

- Cosentino J, Zhao H, Hardin M, Hersh CP, Crapo J, Kim V, Criner GJ; COPDGene Investigators. Analysis of asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap syndrome defined on the basis of bronchodilator response and degree of emphysema. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(9):1483–1489. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201511-761OC.

- Marin JM, Ciudad M, Moya V, Carrizo S, Bello S, Piras B, Celli BR, Miravitlles M. Airflow reversibility and long-term outcomes in patients with COPD without comorbidities. Respir Med. 2014;108:1180–1188. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2014.05.006.

- Tashkin DP, Celli B, Decramer M, Liu D, Burkhart D, Cassino C, Kesten S. Bronchodilator responsiveness in patients with COPD. Eur Respir J. 2008;31(4):742–750.

- Calverley PM, Burge PS, Spencer S, Anderson JA, Jones PW. Bronchodilator reversibility testing in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2003;58(8):659–664.

- Miravitlles M. Diagnosis of asthma–COPD overlap: the five commandments. Eur Respir J. 2017;49(5):1700506. doi:10.1183/13993003.00506-2017.

- National Clinical Guideline Centre. (2010) Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults in primary and secondary care. London: National Clinical Guideline Centre. Available from: http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG101/Guidance/pdf/English (pages 78–81)

- Gibson PG, Simpson JL. The overlap syndrome of asthma and COPD: what are its features and how important is it? Thorax. 2009;64(8):728–735

- Kerstjens HA, Overbeek SE, Schouten JP, Brand PL, Postma DS. Airways hyperresponsiveness, bronchodilator response, allergy and smoking predict improvement in FEV1 during long-term inhaled corticosteroid treatment. Dutch CNSLD Study Group. Eur Respir J. 1993;6(6):868–876.

- Weiner P, Weiner M, Azgad Y, Zamir D. Inhaled budesonide therapy for patients with stable COPD. Chest. 1995;108(6):1568–1571

- Bleecker ER, Emmett A, Crater G, Knobil K, Kalberg C. Lung function and symptom improvement with fluticasone propionate/salmeterol and ipratropium bromide/albuterol in COPD: response by beta-agonist reversibility. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2008;21(4):682–688. doi:10.1016/j.pupt.2008.04.003.

- Papi A, Romagnoli M, Baraldo S, Braccioni F, Guzzinati I, Saetta M, Ciaccia A, Fabbri LM. Partial reversibility of airflow limitation and increased exhaled NO and sputum eosinophilia in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162(5):1773–1777. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.162.5.9910112.

- Queiroz CF, Lemos AC, Bastos ML, Neves MC, Camelier AA, Carvalho NB, Carvalho EM. Inflammatory and immunological profiles in patients with COPD: relationship with FEV 1 reversibility. J Bras Pneumol. 2016;42(4):241–247

- Albert P, Agusti A, Edwards L, Tal-Singer R, Yates J, Bakke P, Celli BR, Coxson HO, Crim C, Lomas DA, et al. Bronchodilator responsiveness as a phenotypic characteristic of established chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2012;67(8):701–708.

- Pérez de Llano L, Cosío BG, Miravitlles M, Plaza V; CHACOS study group. Accuracy of a new algorithm to identify asthma-COPD overlap (ACO) patients in a cohort of patients with chronic obstructive airway disease. Arch Bronconeumol. 2018;54(4):198–204. doi:10.1016/j.arbres.2017.10.007.

- Christenson SA, Steiling K, van den Berge M, Hijazi K, Hiemstra PS, Postma DS, Lenburg ME, Spira A, Woodruff PG. Asthma-COPD overlap. Clinical relevance of genomic signatures of type 2 inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191(7):758–766. doi:10.1164/rccm.201408-1458OC.

- Cosío BG, Pérez de Llano L, Lopez Viña A, Torrego A, Lopez-Campos JL, Soriano JB, Martinez Moragon E, Izquierdo JL, Bobolea I, Callejas J, et al.; on behalf of the CHACOS study group. Th-2 signature in chronic airway diseases: towards the extinction of asthma-COPD overlap syndrome? Eur Respir J. 2017;49(5).pii: 1602397.

- Wagener AH, de Nijs SB, Lutter R, Sousa AR, Weersink EJ, Bel EH, Sterk PJ. External validation of blood eosinophils, FE(NO) and serum periostin as surrogates for sputum eosinophils in asthma. Thorax. 2015;70(2):115–120.

- De Llano LP, Cosío BG, Iglesias A, de Las Cuevas N, Soler-Cataluña JJ, Izquierdo JL, López-Campos JL, Calero C, Plaza V, Miravitlles M, et al. Mixed Th2 and non-Th2 inflammatory pattern in the asthma-COPD overlap: a network approach. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018;13:591–601. doi:10.2147/COPD.S153694.

- Diamant Z, Brusselle G, Russell RE. Toward effective prescription of inhaled corticosteroids in chronic airway disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018;13:3419–3424. doi:10.2147/COPD.S174216.