Abstract

The article analyzes media coverage of migration and refugees from 2015 to 2022 in five selected European countries during the European migration crisis, the adoption of international agreements for their (political) solution, and the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Reporting on migration is found to be primarily shaped by national political context and reflects the most important issues of the time, often portraying migration as a potential threat and invasion. The concepts of “migrant” and “refugee” often overlap in journalistic discourse, which confirms the absence of a clear conceptualization of migration in the media.

Migration is a dynamic phenomenon that requires constant scientific scrutiny and continually molds public perception, notably, under the influence of media and digital social networks. These shifts in understanding are crucial because media discourses both reflect and impact national and local migration experiences and policies. They help set the agenda and frame migration news, making them integral to the (re)conceptualization and (re)contextualization of migration across various epistemic fields, from science to journalism.

Conceptualization is an epistemic process in which concepts are defined and specified, which is essential for translating abstract theories into testable hypotheses in deductive research and for generalizing and making sense of empirical findings in inductive research. Conceptualization influences not only research but also policy decisions and actions as well as media reporting. Reconceptualization occurs when abstract concepts collide with new theoretical insights or are relocated from one disciplinary framework to another. This process may lead to changes in the definitions of concepts. Reconceptualization often results from de- and recontextualization, wherein a concept reemerges in a new social context or environment and alters the position and relationships of the concept within the epistemic field.

While conceptualization defines key elements of a concept, framing narrows and preplans contextualization for concept application. Framing shapes public opinions by emphasizing specific aspects of an issue and using different presentation methods, influencing individual perceptions, opinions, and beliefs. Framing theory distinguishes between agenda setting, which prioritizes issues for public discussion, and framing, which shapes how audiences think about those issues by relating them to key (aspects of) political, economic, and social issues. Media coverage of migration often employs negative frames, linking migration to conflicts, threats to economic prosperity, and cultural identity issues in receiving countries (Fengler, Citation2021, p. 100).

In operational terms, both (re)conceptualization and (re)contextualization involve relocating the concept/issue within a semantic field. While both science and media aim to promote positive epistemic results (Goldman, Citation2010), there are essential differences between the processes of scientific (re)conceptualization and (re)contextualization in the media arising from the fact that the media creates sui generis epistemic systems (Koppl, Citation2006). Science focuses on generating new knowledge, while media contribute to disseminating scientific knowledge and shaping public opinion. In normative terms, the promotion of scientific knowledge in the media would enhance public trust in science and enable a more reliable articulation of facts and opinions expressed in the media, fostering a more rational and informed public (media) discourse. Experientially speaking, however, expecting an alignment between the epistemic realms of science and journalism is unrealistic due to the divergence between the criteria of scientific verification and validation and the criteria of newsworthiness prevailing in the media. Conversely, the introduction of criteria based on media logic and attention-seeking may even compromise the epistemic standards of science (Weingart, Citation2012).

News values like proximity, personalization, eliteness of news actors, timeliness, and conflicting news guide media in deciding what to cover. News stories often adopt either episodic or thematic frames (Iyengar, Citation1996, p. 61). Episodic reports focus on specific events, while thematic reports offer broader, abstract depictions of realities. The concreteness of news increases its agenda-setting power, as audiences can better relate to specific events. In both instances, news comprises elements about which individuals may have very clear preconceptions or “stereotypes,” as observed by Lippmann (Citation1922/1991, p. 330), who coined the term. In such cases, rather than applying the “canon of truth” as a standard of accuracy, readers assess the news based on its conformity to their stereotypes. These “preconceived notions” not only guide the attention and habits of readers but also influence reporters and news organizations, leading to reports that are “stereotyped to a certain pattern of behavior” (Lippmann, Citation1922/1991, p. 243). The significance of stereotypes is particularly pronounced when reporting on value-sensitive and controversial topics such as migration.

Conceptualizing the migrant/refugee binary

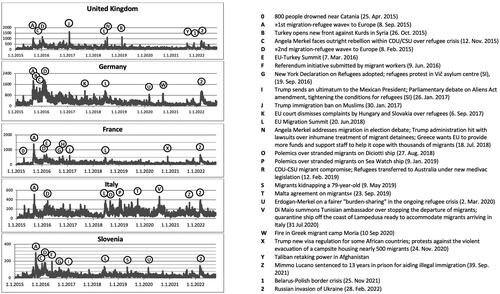

Migration studies have evolved from explaining migration through push and pull factors to more-complex approaches that allow for reconceptualization and specific framing of migration concepts. Transnational and postobjectivist approaches have expanded the understanding of migration as a collective choice driven by larger social units, such as families, and driven by aspirations and desires (Abreu, Citation2012; Massey et al., Citation1993; Taylor, Citation1999, p. 63). The term drivers of migration gained prominence in the 21st century, reflecting a shift in migration research to include more abstract concepts such as “aspiration,” “desire,” and “drivers of migration.” Migration decisions were conceptualized, not as concrete actions of isolated individuals located in one place, but as collective choices of larger units of related people, such as families or households, in which people situated in social fields who may cross borders act together to increase collective income and reduce the constraints and risks not necessarily associated with the labor market (Carling & Collins, Citation2018). shows a similar trend of rapid growth in the use of the term migration drivers in the content of English-language books published between 1960 and 2019. The theoretical reconceptualization of migration exemplifies our assumption about the role of reconceptualizations of migration in media discourse as a reflection of theoretical reconceptualizations alongside situational (historical, experiential, event-related) recontextualizations.

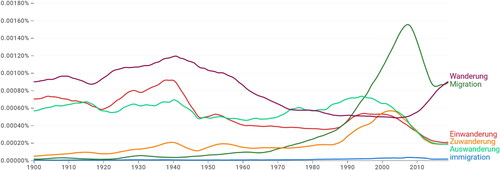

Figure 1. Relative frequencies of selected migration-related concepts in English-language books published within the period from 1960 to 2019. Source: Google Books Ngram Viewer.

Different conceptualizations and explanations of migration also affect public discourse—especially in the mass media, parliamentary debates, and social media—which may serve as “a constituent part of migration as a phenomenon” (van Dijk, Citation2018, p. 230). The importance of public discourse on migration is underscored by the tenfold increase in the annual number of social-scientific publications on migration from 1990 to 2016 (Carling & Collins, Citation2018). In Discourse & Society, a leading international peer-reviewed journal specializing in “research at the boundaries of discourse analysis and the social sciences,” one-third of all articles (227 out of 726) over the last 15 years (2007–2022) have referred to “migration,” “immigration,” “migrant,” or “refugee.” Based on the EBSCOhost database, a total of 89 English-language journal articles have examined media content or effects pertaining to immigration in a European country between January 2000 and June 2018. Half of these articles focus on the years 2017 to 2018. Specifically addressing the so-called European refugee crisis (Eberl et al., Citation2018).

Contrary to recent efforts to offer novel explanations, like “drivers of migration,” the conceptual distinction between migrants and refugees—or “the migrant/refugee binary,” reflecting the legal/illegal realm (Hamlin, Citation2021)—has a longer-standing tradition and remains a crucial conceptual distinction in migration studies, although theorization in the sociology of migration and the field of refugee studies has been retarded by a path-dependent division that could be bridged by greater cooperation (FitzGerald & Arar, Citation2018).

The term migrant lacks a precise and universally agreed-upon definition, let alone one in (inter)national law, with conceptions ranging from portraying migrants as victims at best to considering them as cultural and security threats at worst (Sajjad, Citation2018, p. 1). Such definitions imply a perception of choice and opportunistic decision-making, diminishing sympathy for issues related to the rights and dignity of the individuals involved, and, moreover, challenge the essence of belonging in political discourse (Sajjad, Citation2018, p. 7).

In contrast, the term refugee is clearly but narrowly defined in international law, indicating a person fleeing persecution or conflict in their country of origin. It represents an exception to the sovereign right of states to control their borders, granting those recognized as refugees a privileged legal position compared to other crossers who may also require assistance but lack access to it (Hamlin, Citation2021, p. 2). This simplified binary categorization is not merely a theoretical construct, it carries substantial practical implications, impacting the rights and protection afforded to individuals. However, this distinction, while intentionally or unintentionally reducing the number of asylum seekers, makes “the management of mobile populations more complicated and the recognition of the complex drivers of displacement opaque and confusing” (Hamlin, Citation2021, p. 17).

The legal definition discriminates against those who must migrate due to life-threatening natural conditions, or strategically engineered migration, which may not pose an immediate but a long-term threat to life (Greenhill, Citation2016). The conceptual gray zone of climate-induced and state-organized migration to distinguish migrants and refugees encompasses many aspects, approaches and interpretations of modern migration processes that challenge the conventional distinction between migrants and refugees and opens up space for “popular” populist conceptualizations that have tangible consequences for the rights of immigrants and refugees in the real world. Individuals are assigned various labels, such as refugees, forced migrants, economic migrants, clandestine migrants, illegal migrants, survival migrants, asylum seekers, and vulnerable migrants, which may vary among different interlocutors and change over time (Sigona, Citation2018, p. 456). However, the extensive and intricate range of terms has not prompted the identification of drivers of displacement to facilitate the expansion of the humanitarian safety net. Instead, it has increased the visibility of border crossers and empowered the state to establish hierarchical surveillance systems, making individuals who have crossed multiple borders and disrupted “the natural order of the state-citizen relationship” highly conspicuous (Pickering, Citation2001, p. 172).

Furthermore, significant differences emerge in the conceptions of “the ‘migrant’ in law and policy, the ‘migrant’ in data, and the ‘migrant’ in public debate,” and their correlation with citizenship, exposing a crucial difference between the formal exclusions linked to non-citizenship and the myriad, sometimes informal, exclusions within citizenship (Anderson, Citation2019, pp. 2, 3). Oversimplified or stereotyped conceptualizations of migrants’ identity are often contingent on the specific context; they depend on cultural traditions, group interests, and the differentiation of the group from the outsiders. The inherent problem is that a stereotype determines what group of facts we see, and in what light we see them; it influences the way we think and talk about a group or individual members of a group.

Stereotypical images and phrases, which “provide thematically reinforcing clusters of facts or judgments” (Entman, Citation1993, p. 52), present a convenient framing for media coverage of migration. Generally, the coverage of immigration in the news is largely characterized by a negative tone. Not surprisingly, akin to other underclasses, socially deprived and undesirable groups, “refugees and migrants often appear in the reporting as unadjusted, marginalized, crime perpetrators and/or ‘threats’, and are stereotypically represented” (Camauër, Citation2011, p. 38). A comparative study of news coverage in 15 western European countries and the United States reveals that “immigration and integration” ranks as the third most negatively portrayed topic in political news coverage, following “functioning of democracy, quality of governing, occurrence of scandals” and “crime and judiciary” (Esser et al., Citation2017, p. 80).

While stereotypes may change over the long term, changing them in the short run proves challenging due to the persistent nature of human beliefs, even when experiences contradict the stereotype. However, if a particular incident is striking enough to cause strong discomfort with the established scheme, the stereotype may be shaken to the point of problematizing the accepted way of looking at life (Lippmann, Citation1922/1991, p. 100). Recent analyses of (social) media discourse in the United Kingdom (D’Orazio, Citation2015; Goodman et al., Citation2017) exemplify how the widespread dissemination of a photograph depicting a drowned child triggered a radical shift in the representation of people on the move. Previously labeled as migrants, a negative and problematic category, they were subsequently portrayed in a more humane and compassionate manner, as “refugees.”

Big-data analysis of media coverage of migration

Study design and objectives

The general move toward multidimensional conceptualizations of migration, coupled with global crises and trends instigating migration, increases the need for a more comprehensive sociological perspective on migration rooted in media discourses.

Building on previous research on immigration and refugees, adopting an integrated approach for further investigations proves advantageous—particularly given the existing fragmentation within the field of content analysis, which often fixates on specific media, news brands, time periods, or media languages (d’Haenens & Joris, Citation2019, p. 12). Traditional, human-driven approaches to content analysis are also being challenged by the opportunities presented by big data-analytics and automated content analysis applicable to massive communication data sets. The digitization of content, the availability of big (meta-) data, advances in network analysis methods, and community detection algorithms open up new possibilities for analyzing large communication data sets. These approaches make it possible to identify subtle structures of the relationships between the main concepts under analysis and other co-occurring concepts and to trace the long-term dynamics of (re)conceptualizations.

In the context of this evolving research landscape, this paper aims to achieve two primary objectives:

Identify key concepts, specificities, similarities, and differences in migration-related media discourses in five different countries, focusing on (a) the media coverage of migrant events and processes between 2015 and 2022 and (b) the representation of distinctions, or their absence, between (im)migrants and refugees in different contexts.

Compare conceptual changes and trends in discourses about migrants and refugees in traditional and new media with the vocabulary of critical migration studies—which in English-language books published between 1960 and 2019 leans heavily toward “migration drivers” ()—in order to illustrate our hypothesis of a contradictory relationship between the reconceptualization of migration in the epistemic fields of science and journalism.

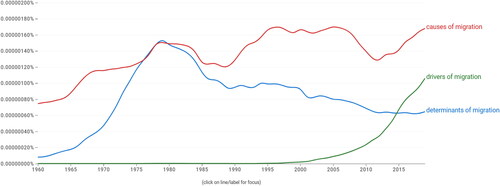

Figure 2. Relative frequencies of the keywords “migrant,” “immigrant,” and “refugee” in English-language books published between 1900 and 2019. Source: Google Books Ngram Viewer.

Our research draws on news stories collected by Event Registry (ER), a comprehensive platform for global media monitoring that provides a centralized repository of event-related data. It collects and organizes information from more than 150,000 news sources including digital newspapers, television, and radio and various forms of digital media such as news aggregator websites and blogs (but excluding social media), in more than 40 languages, that provide details such as event dates, locations, organizations, people, and other relevant information (Eventregistry, Citation2023).

The analysis of migration-related discourses was carried out using news from the United Kingdom, Germany, France, Italy, and Slovenia that was extracted and aggregated by the Event Registry platform. From the total population of 901,125,097 news in the 8-year period from January 1, 2015, to October 13, 2022, on the ER platform, 3,042,912, or 0.3%, relevant news items were selected based on keywords for the analysis of media reporting on migration.

Keywords and observation period

Relying on the Event Registry platform has solved many challenging problems of media source selection, such as accounting for politically biased media, mainstream versus alternative media, national versus local media, and representation of owner interests in media content. The only factor that influences the selection of media is the technical availability of news records. As the ER platform’s news sources are constantly expanding, the inclusion of a particular media source does not necessarily refer to the entire period since the beginning of data collection in 2014. In addition, ER does not contain data from all media sources and/or all news items of a particular media source. Since the system retrieves news items through news feed technology, it includes only news sources that use this technology (Leban et al., Citation2014).

To identify relevant material representing media coverage of migration, the following full-text search terms were selected: refugee, (im)migrant, (im)migration and asylum seeker in five languages (English, French, German, Italian, and Slovene), including lexical and grammatical peculiarities in the selected national languages (e.g., inflectional forms in Slovene). The terms used to refer to people in (the context of) migration differ, sometimes significantly, in the languages of the countries studied. The common vocabulary includes keywords like refugee, migrant, immigrant, and asylum seeker, supplemented in some instances by language-specific terms such as “Einwanderer” or “Zuwanderer,” in German, and “prebežnik” in Slovene.

Applying these keywords to the total population of 901,125,097 news items in the ER platform yielded 3,042,912 relevant news items for migration reporting analysis in the 8-year period from January 1, 2015, to October 13, 2022. For illustration, the keyword COVID was mentioned in 44,676,906 news items; Donald Trump, in 12,636,763; and Brexit, in 3,315,801 news items in the ER platform in the same period.

Semantic annotation

To facilitate computer content analysis of big data, the documents were first enriched with metadata, which makes unstructured content easier to process. Through automatic semantic annotation on each news item, we identified text fragments mentioning or naming entities described in a semantic repository and assigned relevant information to them. For entity recognition, we utilized Wikifier software (https://wikifier.org/). Wikifier is a web service that searches a text document for terms that match terms in Wikipedia’s semantic repository, linking each identified term to the corresponding Wikipedia entry. Terms identified in the analyzed texts of news items are categorized as “entities” (concrete terms like names of people, organizations, and locations) and “non-entities” (concepts or abstract terms). The wikification process involves three main stages: (a) identifying phrases or words in the input document that refer to a Wikipedia article, (b) determining the exact Wikipedia articles to which a phrase or word refers, and (c) selecting relevant concepts that should be included in the system’s output according to their significance for the document based on the page rank (see Brank et al., Citation2017). In contrast to the classic string search, which finds only words that exactly match the search term(s), the semantic annotation also identifies a (non)entity as such when designated differently (e.g., Angela Merkel, German PM, Merkel, Bundeskanzlerin).

Wikifier assisted in identifying and selecting the most relevant organizations, locations and concepts mentioned in the news referring to refugees and (im)migrants in English, French, Italian and Slovene, along with semantically related terms in German and Slovene.

Visualization of migration vocabularies

Utilizing network analysis, we examined pairs of annotated terms within the same news item, aiming to identify the semantic proximity between them. By aggregating this data across news items published within a specific timeframe and country and creating networks of these terms based on the frequency of their co-occurrence in the news, we identified prominent terms within shared or contested “migration vocabularies.” Subsequently, Gephi software (Bastian et al., Citation2009) was used to analyze and visualize the spatial distribution or network of terms. Given the densely interconnected section of the network representing shared vocabulary, nodes (representing keywords and terms in the data set) are arranged to amplify their distinctiveness and more accurately illustrate relationships among different groups of terms and keywords. The thickness of links (edges) connecting nodes mirrors the overall frequency of co-occurrence of different terms and keywords in the same news item.

Country selection

The analysis of migration-related discourses was carried out using news stories from the United Kingdom, Germany, France, Italy, and Slovenia, extracted and aggregated by the Event Registry platform. These countries were chosen for their roles in shaping EU policy and different views on migrations. Some of them are considered destination countries (UK, Germany, and France), countries on the external borders of the EU (Italy), and/or transit countries (France, Slovenia). Using a sample of countries with different geopolitical locations, it was also possible to address the question of whether national discourses on migration reflect their migration-specific societal environment.

The Event Registry platform monitors technically accessible digital media in each country, which may not be representative of the total digital media landscape. The sample size for both media coverage and migration news recorded by ER is sizeable but not statistically representative due to variations in media coverage across countries. Despite this limitation, collecting all technically available information helps avoid systematic biases in the sample.

The data collected in this study is big data in nature—a large amount of unstructured data that is not representative of a predefined population of entities and, thus, not intended to draw inferences or generalize from a sample to a population, as can normally be done with survey data. The findings cannot therefore be generalized to individual countries, nor can countries be directly compared in terms of frequency distribution and statistical inference.

Results

Scientific versus journalistic conceptualization

To identify conceptual changes and trends in media discourses related to migration, the analysis identifies the structural and dynamic features of media coverage throughout the analyzed period by examining the prominence of various terms that denote people on the move. The dynamic features are reflected in the temporal distribution of news items containing the search terms and indicate key periods and events in the media coverage.

Conceptualizations of migration as the actual and potential mobility of individuals from one social setting to another depend on their specific epistemic framework or epistemic agent, which can vary widely. The idea of drivers as complex forces that lead to the initiation of migration and sustain it over time is a typical example of a scientific reconceptualization that might also influence other epistemic systems. Given the differences between the scientific and journalistic epistemic systems and the findings of numerous studies on the key “news factors” or “news values” that journalists weigh when deciding whether or not to cover an event (see Harcup & O’Neill, Citation2016), it is unrealistic to expect the media to follow the trends of scientific reconceptualizations in their framing.

Based on methodological similarities in operationalization with keywords, we wanted to find out whether the main ideas of the scientific (re)conceptualization of migration focusing on the “drivers of migration” also appear in media discourses on migration. To assess whether the coverage of migration aligns with or considers the theoretical reconceptualization, we investigated how the news on migration relates to the 15 terms that Carling and Collins identified as indicators of reconceptualization that attributes greater explanatory power to the more abstract “drivers” of migration (). We conducted the analysis exclusively on news published in Great Britain in English, totaling 30,059,329 news items, as the terms denoting migration triggers are not unambiguously translatable to other languages.

Table 1. Relative frequencies of terms indicating the reconceptualization of migration that appeared in UK news stories aggregated on the Event Registry platform (in percentages, January 1, 2015, to November 17, 2022; Source: Event Registry).

The analysis shows a kind of epistemic radiation of the critical (re)conceptualization of migration across the borders of the scientific into the journalistic system, although it is not very strong. Among all indicators of changes in the conceptualization of migration defined by Carling and Collins, the most represented in media coverage worldwide are hope, expectation, risk, and waiting. All other 11 indicators appear in less than 10% of the news, with the lowest, yearning, found in less than 1% of the news. The inclusion of all 15 indicators in the media discourse does not show variability depending on whether the news reported on “refugees” or “immigrants.” Moreover, critical indicators of migration, integral to the reconceptalization of migration in critical migration theorizing, are largely absent in the news coverage of migrants and/or refugees as actors.

International migration politics as a media blind spot

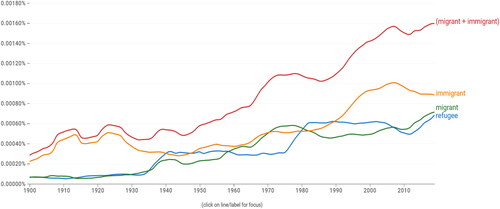

The media tends to give limited attention to scientific innovations in the study of migration or to international agreements concerning the urgent challenges of international migration. Domestic news takes precedence over international news, except for events prioritized based on classical news values, such as significant (negative) consequences, emergency situations, or involvement of prominent individuals. In the Italian media, major highlights were primarily linked to national events, such as those on the island of Lampedusa, and agreements concerning migrants. In Slovenia, coverage focused on events along the “Balkan migration route.” British media witnessed a peak in migration-related news on June 24, 2016, with 799 stories (12.2% of all news that day) following the Brexit referendum vote. Only in Germany and France did the first (2015) and second “migration wave” (2016) to Europe dominate. French media also paid considerable attention to situations in Syria, Libya, and Turkey as departure countries for migrants, along with refugee camps in Paris and Calais.

While there seems to be a period of relatively less media attention to migration-related topics in the UK, Germany, and France in the middle of the analyzed period, media attention to migration remained considerable in the EU peripheral countries. The periods with the highest amount of news on migration in Italy and Slovenia were the years 2018–2020. In Italy, the most prominent events were of national origin, while Slovenian media covered extensively migrants on the Balkan route.

Media in most of the analyzed countries demonstrated heightened attention to international events, such as the first and second migration-refugee wave to Europe, Trump’s immigration ban, the Taliban resumption of power in Afghanistan, the crisis on the Belarusian-Polish border, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine. However, international political debates on migration received very little media coverage. Of the two compacts—the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly, and Regular Migration (GCSORM) and the Global Compact for Refugees (GCR)—the former, with a total of 593 news reports in five languages, was mentioned in 187 news stories published in the United Kingdom, in 233 in Germany, in 92 in France, in 26 in Italy, and in 55 in Slovenia and the latter, with a total of 940 news reports including 588 in Germany and 76 in Italy but fewer in the United Kingdom, France, and Slovenia (). The attention given to the two compacts consistently stayed below 1% of all daily coverage, remaining scarcely noticeable in the media after the day they were adopted. By comparison, the coverage of Trump’s executive order of January 30, 2017, banning Muslim immigrants from entering the United States reached 7.7% of all news published in the British media on that day.

Except in the most “newsworthy” events, international migration news becomes a priority only when it can be domesticated. A typical example is the first and second wave of refugees in Europe, when due to the intended arrival of migrants in Western Europe, events on the “Balkan route” were widely reported everywhere as almost domestic news. Apart from the most critical foreign migration events reported in all countries—the Taliban resumption of power in Afghanistan, Trump’s Muslim immigration ban, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine—most of the highlights of media coverage of migration in all countries were linked to local events (). On June 17, 2019, the British media exhibited increased attention to the GCR, with 40 news items, surpassing the day of its adoption, while reporting on a statement by British MP Sajid Javid that the United Kingdom intends to resettle 5,000 refugees in 2020. In November 2018, Slovenian media devoted considerable attention to the GCSORM, not due to the compact itself, but because right-wing media in Slovenia utilized the parliamentary debate on GCSORM to publish a series of comments against migrants.

Discursive construction of refugees and (im)migrants

The prominence of the key terms related to migration and trends in their use indicate that migration was referred to and contextualized differently in different countries during the analyzed period. Reporting on migration-related topics revolves around three main actors labeled as “refugees,” “migrants,” and “immigrants.” The use of the term immigrant/s was the most prominent in the British news, while the term migrant/s prevailed in the French and Italian media, which is consistent with the general trend detected by Google Ngram Viewer ().

Figure 4. Changes in the share of reporting on refugees relative to total reporting on refugees and (im)migrants in the media of the five analyzed countries (2015–2022), illustrated by smoothed indexes.

In all countries except Germany, the terms migrant and/or immigrant are more often used than refugee (see and ). In Germany, news containing refugees represented 2.2% of news items published and aggregated in the Event Registry in the selected period, in contrast to 1.7% of news reporting (im)migrants (including terms “Einwanderer” and “Zuwanderer”). In the United Kingdom, 2.0% referred to (im)migrants and 0.9% to refugees; in France 1.8 to (im)migrants and 1.0% to refugees; in Italy 2.1 to (im)migrants and 0.5% to refugees; and in Slovenia 2.1 to (im)migrants and 1.4 to refugees.

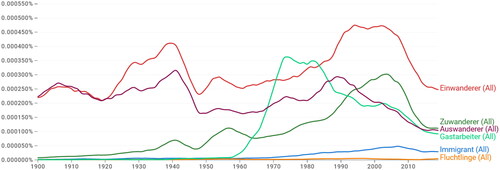

Figure 5. Relative frequencies of the native and borrowed terms denoting the processes of migration in German-language books published between 1900 and 2019. Source: Google Books Ngram Viewer.

Table 2. Media coverage of migration: number of news stories containing specific search term in the analyzed period, January 1, 2015, to Oct. 13, 2022.

In the United Kingdom, news stories reporting migration-related issues were mostly focused on “immigration” or “immigrants,” followed by “migration” and “migrants,” while “refugee(s)” were mentioned in 260,028 news items. Apart from the period of the “European migrant crisis,” the term immigrant dominated the British media until the retakeover of power in Afghanistan by the Taliban in August 2021 and especially with the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, which brought the term refugee back into the media discourse. In contrast, people who were caught and forcibly brought to the Belarusian-Polish border were clearly labeled as “migrants.” Similar patterns were found in the French and to some extent in the Italian media.

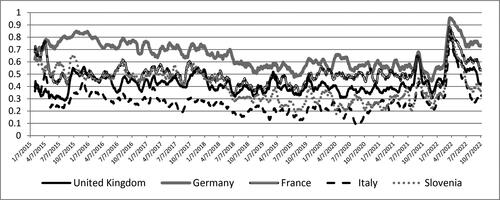

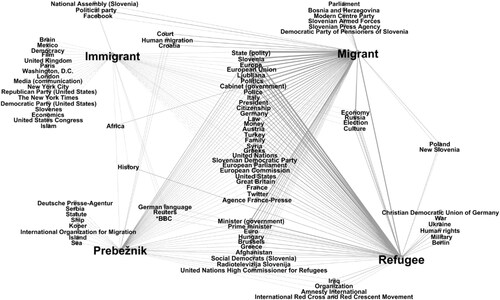

In the German media, the terms refugee (“Flüchtling” or “Geflüchtete”) and asylum seeker (“Asylbewerber,” “Asylantragsteller, “ or “Asylsuchende”) were most often used to denote people on the move, rather than the term immigrant (“Immigrant,” “Immigrantin”), which led to a distinctive peak on July 2, 2018, during the so-called Migrationstreit (Süddeutche Zeitung, Citation2018) or Asylstreit (Die Welt, Citation2018) in the German coalition government. Even when the German terms “Einwanderer” and “Zuwanderer”—synonymous with the term Immigrant as a direct equivalent to the English term immigrant—are taken into account, the term refugee, with 655,000 appearances, still dominated in the media discourse. A similar example of specific word formation can also be found in Slovenian media where the third most common term in reporting on migrants was “prebežnik” (“defector”), which refers to someone who has abandoned their country or cause in favor of the counterpart or opposite (e.g., deserter). These specific cases of word formation point to the importance of (re)contextualization of concepts as a reflection of the specificity of national contexts, which makes media discourses contingent on national experiences of migration.

At the beginning of the war in Ukraine, the share of reporting on refugees increased significantly and began to dominate in all languages and countries but then—except in Germany—soon fell back below 50%. As shows, apparently in these countries the word refugee became more popular than migrant only in reference to the war in Ukraine, when racial and religious prejudices fell away. This is in marked contrast to the situation before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, when, for example, Cooper et al. (Citation2021) found that people arriving in the United Kingdom from the Middle East and North Africa were more likely to be portrayed as “refugees” than migrants coming from Europe.

In the period before the invasion of Ukraine, the word refugee is used only occasionally and insignificantly more often than migrant. That was the case in reporting the so-called first refugee wave to Europe in autumn 2015, particularly in the United Kingdom, in Germany, and to some extent in France and Slovenia but not in Italy. The term migrant was most commonly used already during the first refugee wave in France and Slovenia and during the “second refugee wave” in the United Kingdom. Afterwards, there is a gradual decrease in news referring to “refugees” in the media discourse and a gradual increase in the use of the term migrant (particularly in France and Slovenia) and immigrants (UK). The number of news stories using the term refugee in the United Kingdom media gradually declined between September 9, 2015, (619 news stories) until the start of the second refuge wave in early 2016, when use of the term briefly rose again to 562 on January 14, 2016. During coverage of U.S. President Trump’s Muslim immigration ban, the use of the term refugee again dominated British media discourse for a very short time (1,042 news items on January 30, 2017), followed by an immediate drop (688 news stories on January 31, 29). A similar pattern was found in France (a drop from 459 to 254 news stories) and Slovenia (from 75 to 56).

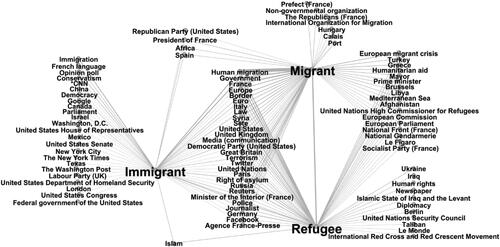

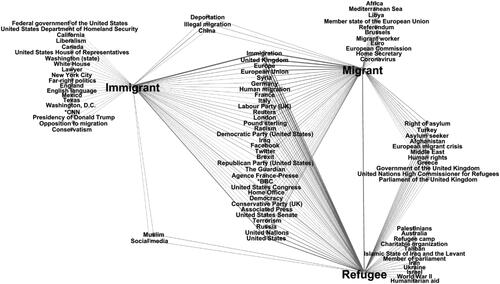

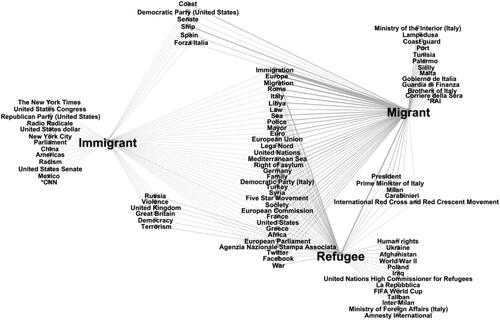

The share of news items about refugees that also mention migrants or immigrants varies from 43% in the case of Italy (38,481), followed closely by Great Britain with 40% (102,678 news items), France with 34% (68,155), and Germany with 24% (155,863).Footnote1 Apparently, refugees and (im)migrants in the media discourses in all analyzed countries largely share the same semantic contexts, regardless of whether the primary agents in the media coverage of migration are (im)migrants or refugees (). The term refugee is closely related to the material environments and circumstances that refugees leave behind. In the case of the French and British media, these are mainly geographical denotations (Syria, Arabs, Palestinians, Kurds, Ukrainians) and terms related to war and the army (civil war, military, airstrike, torture, ceasefire, war, world war, bombardment).

Immigrant, in contrast, is more closely related to political, economic, and legal issues associated with migration in incoming countries. When referring to immigrants, events and topics are reported in the media that uniquely connect national power actors to immigrants and the way they are treated in the countries in where immigrants arrive. National political institutions, regulatory systems, and ideologies typically appear in reporting on “immigrants.” In France, this term is used in reference to the political system and ideological issues. In the British media, “immigrant” more often refers to government, elections, politicians, university, religion, judges, and progressivism than to migration itself. A typical example of an “immigrant situation” that was reported by all media during the analyzed period was the arrival of “immigrants” at the Mexican-U.S. border and the Trump administration’s crackdown on “immigrants.”

Whether reporting on “migrants,” “immigrants” or “refugees,” Italian migration reporting generally places a strong emphasis on domestic political topics. Unlike the British and German media, Italian media does not systematically use the term “rifugiato” (refugee) in connection with migrants from war-affected regions. The distinctive terms associated with refugee in Italian media often have religious connotations or allude to war without specifying a geographic area.

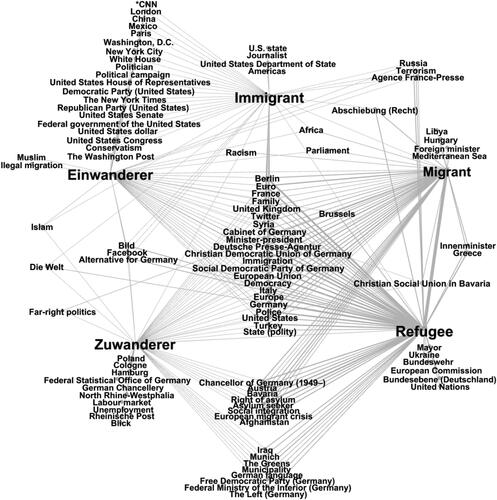

The discourse of the German media is specific in that it does not use the generic international (English) term immigrant, but instead uses the original traditional German words “Zuwanderer” and “Einwanderer.” The term migration has dominated the German literature for the last three decades; whereas, previously the German term “Wanderung” (and “Einwanderung” and/”oder Zuwanderung”) was dominant (). “Zuwanderung” or “Einwanderung” means migration from the point of view of the country to which people are coming (immigration); from the point of view of the other country, these people are “Auswanderer” (emigrants). However, the native terms “Einwanderer” and “Zuwanderer” are much more often used to refer to people in migration (). The former emphasizes the act of immigration and settling into a new country, while the latter focuses on the act of migration toward a particular destination, regardless of the permanence or duration of the move, but the specific choice and interpretation of these terms can vary in different contexts.

Figure 6. Relative frequencies of the keywords “Immigrant,” “Einwanderer, “ “Zuwanderer, “ “Flüchtling, “ “Gastarbeiter, “ and “Auswanderer” in German books published between 1900 and 2019. Source: Google Books Ngram Viewer.

Figure 7. Top 20 terms associated with refugees, immigrants, migrants, (Zu-) and Einwanderer in German media 2015–2022. Source: Eventregistry. N = 107 words.

Figure 8. Top 20 terms associated with refugees, immigrants, and migrants in French media 2015–2022. Source: Eventregistry. N = 95 words.

Figure 9. Top 20 terms associated with refugees, immigrants, and migrants in UK media 2015–2022. Source: Eventregistry. N = 95 words.

Figure 10. Top 20 terms associated with refugees and migrants in Italian media 2015–2022. Source: Eventregistry. N = 92 words.

Figure 11. Top 20 terms associated with refugees and migrants in Slovenian media 2015–2022. Source: Eventregistry. N = 100 words.

In principle, the dominant use of the word migrant in European media discourses is consistent—but not so clearly dominant—with the inappropriate designation of displaced persons who cannot go home as migrants even in cases where the persons reported are not migrants but asylum seekers or refugees, as recently identified in the New York Times and American radio and television stations (Benedict, Citation2022). It is hard to believe that journalists are not aware of this distinction, and yet, like the anti-immigration politicians, they deliberately use the term migrant to promote prejudice, xenophobia, and racism.

The differences in the epistemic contextualization of the terms refugee and (im)migrant in media coverage point to a rather weak conceptual distinction between refugees and migrants. First, the epistemic field, which in the analyzed discourses is common to the refugee and the immigrant, is significantly wider in terms of the number of related terms than the two specific fields with terms that are exclusively related to either the term refugee or (im)migrant. Second, the specific epistemic fields of “refugee” and “(im)migrant” differ between the languages analyzed, implying wider cultural differences between the countries analyzed. Third, in all three epistemic (sub)fields, words with a higher degree of concreteness—that is, words that have direct sensory or operational referents (material, tangible, identifiable things, actions, and properties)—dominate. Fourth, despite the prevalence of concrete, ostensive terms, the analysis does not reveal a difference in greater empathy and solidarity toward supposedly more-vulnerable refugees than toward migrants. Overall, the precise use and interpretation of these terms may vary in different contexts, and the specific choice of word may depend on individual preferences or specific legal and administrative frameworks.

This suggests that the distinction between the two terms is not systematic and based on a clear conceptualization but is experiential and corresponding to the sensorial and affective contextualization. The epistemic (sub)fields of “refugee” and “(im)migrant” differ mainly in concrete actors, institutions, and actions, representing concrete events in which either “refugees” or “immigrants” were reported to be involved. It is thus understandable that the abstract content of the two international compacts on migration (GCSORM and GCR) from 2018 did not receive much media attention anywhere—except in connection with concrete national political actors and actions, as in the case of Slovenia and the United Kingdom—in contrast with Trump’s ban on the entry of immigrants from Arab countries into the United States, with a concrete actor, targets, and action open to evaluation ().

Table 3. Media vocabularies: Top 15 keywords associated with “refugees” and “migrants” in media reporting (n = 7,005,509 news items between January 1, 2015, and October 13, 2022).

Conclusion

Given the evolving migration landscape, dynamic patterns of human movement and regulatory shifts, accurate reporting, and categorizing migration poses considerable challenges. Our research reveals a tendency in media coverage to depict migration, particularly Arab/African migration, as a potential threat or invasion. In contrast, when reporting on refugees, the media often emphasizes humanitarian aspects, conveying more-positive narratives, highlighting critical trends in human mobility and potential reforms to the regulatory framework. This trend is especially observed in cases involving culturally similar countries.

Despite the clear conceptual and legal distinctions between refugees and migrants, the media frequently uses these terms interchangeably. The study underscores that empirical contextualizations exert a more substantial influence on media coverage of migration than theoretical conceptualizations. The impact of innovative conceptual approaches in migration research does not readily translate into global media coverage. Instead, news-related factors and values rooted in specific social contexts play a more pivotal role. The divergence between scientific and journalistic epistemic spaces, with distinct knowledge systems and agents, contributes to this disparity.

The divergence between the epistemic spaces of science (migration studies) and journalism is also apparent in relation to the abstract—concrete dichotomy (or continuum) of epistemic outcomes. While science engages with abstract concepts like “drivers” in migration studies, journalism focuses on reporting concrete events, visualizing them with tangible entities such as places, individuals, and institutions. Media coverage of migration is significantly influenced by the national political context, often reflecting the prevalent issues of the time.

In journalistic discourse, the concepts migrant and refugee often overlap, highlighting the lack of a precise conceptualization of migration in the media. The term migrant is more commonly used than refugee, with variations in prevalence over time and across regions. Geopolitical connotations are attributed to these terms, with refugee-related discourse prominent in cases like the Russian invasion into Ukraine, while migration discourse centers on Arab/African and Latin American migrations. Individuals fleeing the devastating consequences of climate change, poverty, economic instability, and political conflicts in Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America are typically categorized as (im)migrants, rather than refugees, despite arguably fleeing their homelands with a “well-founded fear” for their lives. Conversely, Ukrainian citizens leaving their country due to the war are consistently labeled as “refugees.” This contrast underscores the media’s tendency to differentiate between migrants and refugees based on geographic and cultural proximity to the European Union and the United Kingdom.

In summary, media portrayals often frame migration as a potential threat, especially for Arab/African migration, while reporting on refugees combines elements of threat, humanitarianism, and positive narratives. Differentiations between refugees and immigrants also reflect linguistic idiosyncrasies, with some languages favoring indigenous terms such as “Flüchtling,” “Geflüchtete,” and “Asylbewerber” over the “international” terms for Immigrant and Migrant in German. Nevertheless, overall, news stories on these two categories of people on the move share very similar associated terms.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Sara Hanke and Raphael Heiko Heiberger of the University of Stuttgart for their help and discussions that led to the results presented in this article. The authors would also like to thank our colleague Gašper Koren for his help with data collection.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Due to the large number of inflectional forms in the Slovenian language and the limitations of the ER software, it is not possible to calculate data for Slovenia, but we estimate that the overlap is between 30% and 40%.

References

- Abreu, A. (2012). The new economics of labor migration: Beware of neoclassicals bearing gifts. Forum for Social Economics, 41(1), 46–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12143-010-9077-2

- Anderson, B. (2019). New directions in migration studies: Towards methodological de-nationalism. Comparative Migration Studies, 7(1), 36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-019-0140-8

- Benedict, H. (2022). Why we should think twice before using the term ‘migrant’. Columbia Journalism Review, October 20. https://www.cjr.org/

- Bastian, M., Heymann, S., & Jacomy, M. (2009). Gephi: an open source software for exploring and manipulating networks. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, 3(1), 361–362. https://doi.org/10.1609/icwsm.v3i1.13937

- Brank, J., Leban, G., & Grobelnik, M. (2017). Annotating documents with relevant Wikipedia concepts. Proceedings of the Slovenian Conference on Data Mining and Data Warehouses.

- Camauër, L. (2011). ‘Drumming, drumming, drumming’: Diversity work in Swedish newsrooms. In E. Eide & K. Nikunen (Eds.), Media in motion: Cultural complexity and migration in the Nordic Region (pp. 37–51). Ashgate.

- Carling, J., & Collins, F. (2018). Aspiration, desire and drivers of migration. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 44(6), 909–926. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1384134

- Cooper, G., Blumell, L., & Bunce, M. (2021). Beyond the ‘refugee crisis’: How the UK news media represent asylum seekers across national boundaries. International Communication Gazette, 83(3), 195–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048520913230

- d’Haenens, L., & Joris, W. (2019). Images of immigrants and refugees in Western Europe. In L. d’Haenens, W. Joris, & F. Heinderyckx (Eds.), Images of immigrants and refugees in Western Europe (pp. 7–18). Leuven University Press.

- D’Orazio, F. (2015). Journey of an image: From a beach in Bodrum to twenty million screens across the world. In F. Vis & O. Goriunova (Eds.), The iconic image on social media: A rapid research response to the death of Aylan Kurdi (pp. 11–18). Visual Social Media Lab. https://research.gold.ac.uk/id/eprint/14624/1/KURDI%20REPORT.pdf

- Die Welt. (2018). Der Unions-Kompromiss im Asylstreit. July 2. https://www.welt.de/newsticker/dpa_nt/afxline/topthemen/hintergruende/article178646068/Der-Unions-Kompromiss-im-Asylstreit.html

- Eberl, J.-M., Meltzer, C. E., Heidenreich, T., Herrero, B., Theorin, N., Lind, F., Berganza, R., Boomgaarden, H. G., Schemer, C., & Strömbäck, J. (2018). The European media discourse on immigration and its effects. Annals of the International Communication Association, 42(3), 207–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2018.1497452

- Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

- Esser, F., Engesser, S., Matthes, J., & Berganza, R. (2017). Negativity. In C. H. de Vreese, F. Esser, & D. N. Hopmann (Eds.), Comparing political journalism (pp. 71–91). Routledge.

- Eventregistry. (2023). Media monitoring. https://eventregistry.org/products/monitor/

- Fengler, S. (2021). Migration coverage – Media effects and professional challenges. In S. Fengler, M. Lengauer, & A.-C. Zappe (Eds.) Reporting on migrants and refugees (pp. 113–134). UNESCO.

- FitzGerald, D., & Arar, R. (2018). The sociology of refugee migration. Annual Review of Sociology, 44(1), 387–406. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-073117-041204

- Goldman, A. I. (2010). Why social epistemology is real epistemology. In A. Haddock, A. Millar, & D. Pritchard (Ed.), Social epistemology (pp. 1–28). Oxford University Press.

- Goodman, S., Sirriyeh, A., & McMahon, S. (2017). The evolving (re)categorisations of refugees throughout the “refugee/migrant crisis”. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 27(2), 105–114. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2302

- Greenhill, K. M. (2016). Strategic engineered migration as a weapon of war. Suffolk Transnational Law Review, 39(3), 615–636.

- Hamlin, R. (2021). Crossing: How we label and react to people on the move. Stanford University Press.

- Harcup, T., & O’Neill, D. (2016). What is news? Journalism Studies, 2(2), 261–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616700118449

- Iyengar, S. (1996). Framing responsibility for political issues. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 546(1), 59–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716296546001006

- Koppl, R. (2006). Epistemic systems. Episteme, 2(2), 91–106. https://doi.org/10.3366/epi.2005.2.2.91

- Leban, G., Fortuna, B., Brank, J., & Grobelnik, M. (2014). Event Registry. Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on WorldWideWeb—WWW ‘14 Companion. https://doi.org/10.1145/2567948.2577024

- Lippmann, W. (1922/1991). Public opinion. Transaction Publishers.

- Massey, D. S., Arango, J., Hugo, G., Kouaouci, A., Pellegrino, A., & Taylor, J. E. (1993). Theories of international migration. Population and Development Review, 19(3), 431–466. https://doi.org/10.2307/2938462

- Pickering, M. (2001). Stereotyping: The politics of representation. Palgrave.

- Sajjad, T. (2018). What’s in a name? ‘Refugees’, ‘migrants’ and the politics of labelling. Race & Class, 60(2), 40–62.

- Sigona, N. (2018). The contested politics of naming in Europe’s “refugee crisis”. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 41(3), 456–460. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2018.1388423

- Süddeutche Zeitung. (2018). Wie weit liegen die Koalitionspartner auseinander?. July 2. https://www.sueddeutsche.de/news/politik/migration-wie-weit-liegen-die-koalitionspartner-auseinander-dpa.urn-newsml-dpa-com-20090101-180702-99-977785

- Taylor, E. J. (1999). The new economics of labour migration and the role of remittances in the migration process. International Migration (Geneva, Switzerland), 37(1), 63–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2435.00066

- van Dijk, T. A. (2018). Discourse and migration. In R. Zapata-Barrero & E. Yalaz (Eds.), Qualitative research in European migration studies (pp. 227–245). Springer.

- Weingart, P. (2012). The lure of the mass media and its repercussions on science. In S. Rödder, M. Franzen, & P. Weingart (Eds.), The sciences’ media connection: Public communication and its repercussions (pp. 17–32). Springer.