Abstract

Background

Although mortality attributed to illicit drugs is a significant contributor to the overall number of deaths worldwide, knowledge relating to the consequences for those bereaved by drug-related deaths (DRDs) is scarce. Since individuals with substance use disorders are prone to stigma, there is an urgent need for knowledge about the occurrence and content of stigmatization of those bereaved by DRDs.

Method

A mixed methods approach was used. In total, 255 participants (parents, siblings, children, partners, other family members and close friends) who had lost a person to a DRD were recruited. Thematic and descriptive analyses were undertaken on data derived from open-ended and standardized questions from a large survey exploring systematically the contents of interpersonal communication experienced by participants following their bereavement.

Result

Nearly half of the respondents reported experiencing derogatory remarks from close/extended family and friends, work colleagues, neighbors, media/social media and professionals. The main themes were dehumanizing labeling, unspoken and implicit stigma, blaming of the deceased and that death was the only and the best outcome. The remarks were negative and powerful despite being directed at people in crisis and originating from individuals close to the bereaved participants.

Conclusion

Individuals bereaved by DRDs experience harsh and stigmatizing communications reflecting the existing societal stigma toward drug users. This contributes to the marginalization of grieving individuals at a time when they may require support. Making people aware that stigma occurs, why it happens and how it is transmitted in society can help reduce it and its adverse consequences.

Introduction

Mortality associated directly or indirectly with illicit drug use is a major contributor to the number of adult deaths worldwide (European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA Citation2019). Drug-related deaths (DRDs) have marked negative consequences, not at least for all the people close to the deceased that are left behind. Despite vast numbers of people being bereaved by DRDs, the field is in urgent need of knowledge about how the bereaved deal with grief. Key questions that need to be explored are bereaved people’s needs for support and help, and how bereavement processes may be impacted and complicated by the stigma associated with a DRD. In Norway, with a population of five million people, there are approximately 300 DRDs per year. This is an incidence rate of approximately six cases per 100,000 and is comparable to other Scandinavian countries (EMCDDA Citation2019). In the United States, DRDs reached what could be described as epidemic proportions in 2017, when the age-adjusted rate of drug overdose deaths (21.7 per 100,000) was 9.6% higher than the 2016 rate (19.8 per 100,000). This negative trend has also been observed in most European countries. The mortality rate due to overdose in 2017 was, for example, estimated at 22.6 deaths per million population aged 15–64 (EMCDDA Citation2019, p. 80). More than 200,000 people die from illicit drug overdoses every year and this figure is higher when DRDs are included, e.g. deaths related to HIV, hepatitis C and infections. It is estimated that 10–15 people close to the deceased are bereaved, which means that globally, 2–2.5 million people are bereaved by a DRD every year. Despite this large number, knowledge of this group is remarkably limited and there is therefore a need to better understand the experiences of the individuals impacted by DRDs.

Despite the increased interest among experts in the field of grief (Stroebe et al. Citation2012), a recent systematic review documents that limited research has been carried out into how individuals experience bereavement brought on by the death of a person close to them as a consequence of drug use (Titlestad et al. Citation2019). The few studies that exist in this field indicate that people bereaved by DRDs experience a significant emotional and existential burden after death. It has, for example, been found that significant grief reactions, lack of understanding or help from support systems and stigmatization, both from wider society and self-inflicted, influence the bereavement process (Titlestad et al. Citation2019). This systematic review highlights that people bereaved by DRDs have a great need for a culture of caring and that there is reason to believe that their experiences, as well as the perceived and self-inflicted stigma, complicate the grieving process. The systematic review called for further research to explore the stigma associated with DRDs. Toward filling this gap, the present article will contribute relevant knowledge by describing how people bereaved by DRDs are regarded by others in the context of widespread stigmatizing attitudes toward substance users.

Stigma

Goffman (Citation1963, p. 3) described stigma as an attribute that is deeply discrediting and reduces someone from ‘a whole and usual person to a tainted and discounted one.’ Stigma has been conceptualized as a stereotype (negative beliefs), prejudice (agreement with negative beliefs) and discrimination (behavioral response to prejudice, such as avoidance or withholding opportunities) (Corrigan and Watson Citation2002). According to Link and Phelan (Citation2001), stigma occurs when interrelated components as labeling, stereotypes, separation (us/them), status loss and discrimination converge. Thus, stigma is a complex social problem that operates at interpersonal, intrapersonal and structural levels (Link and Phelan Citation2001, Hatzenbuehler and Link 2014, Henderson and Gronholm Citation2018).

It has also been established that interpersonal or social stigma emanates from the stigmatized group’s attitudes and behaviors, including the endorsement of stereotypes and results in social distance and discriminatory behavior from those who look down on the stigmatized group (Henderson and Gronholm Citation2018). Intrapersonal or self-stigma arises when an individual who experiences being discredited by others internalizes the social stigma. Corrigan and Rao (Citation2012) outline a staged approach to self-stigma within individuals: awareness of social stigma, agreement with social stigma and application of social stigma to their own experience. In addition, self-stigma may render individuals less likely to challenge dominant views (Link and Phelan Citation2001), thereby reinforcing them. Structural stigma has been defined as the ‘societal-level conditions, cultural norms and institutional practices that constrain the opportunities, resources and well-being for stigmatized populations’ (Hatzenbuehler and Link 2014, p. 2) and impacts many systems (social, employment, education, social services, justice) as well as healthcare domains (Henderson and Gronholm Citation2018). Livingston (Citation2013), in a similar way, highlights that structural stigma may be intentional (e.g. policies or practices denying access or equality to individuals) or inadvertent (e.g. lack of funding or accommodation, which makes it more challenging to detect). Stigma embedded in wider social structures therefore reinforces other forms of stigma and may reduce access to services and negatively impact health (Hatzenbuehler and Link 2014). More recently, Sheehan and Corrigan (Citation2020) highlight how stigma affects access to healthcare, showing that the stigmatized people may both avoid health services while, at the same time, health services may avoid stigmatized groups with adverse impacts on the quality and content of the service offered. This body of research therefore illustrates how stigma operates at different levels and can present considerable obstacles to how people can obtain help for their social and health challenges. However, to date it is not known how these dynamics influence the life situation of those bereaved by DRDs.

Importantly, in the context of bereavement after DRDs, Goffman (Citation1963) highlights that the family, to a certain degree, may be forced to share the discredit that is associated with ‘their’ stigmatized member and, in this way, can become stigmatized themselves. Sheehan and Corrigan (Citation2020) conceptualize this as associative stigma, that describes how family members, friends, health workers or other acquaintances may be tarnished by stigma through their connections to the stigmatized individual. Although there is very little research-based knowledge relating to the way in which people bereaved by DRDs experience such stigmatization by association, several studies illustrate that individuals with a history of substance use are exposed to stigma. A systematic review of the stigma associated with substance use in non-clinical samples, in this way, indicates that the general population holds stigmatized views of those with substance use disorders (SUDs) and that the level of stigma is greater in relation to people with SUDs than those with psychiatric disorders (Yang et al. Citation2017). Similarly, a systematic review of stigmatization by health professionals regarding individuals with SUDs concluded that negative attitudes of health professionals are common and contribute to suboptimal healthcare provided for these patients (Van Boekel et al. Citation2013). A study that compared stigmatizing attitudes toward those with SUD among different stakeholders (general public, general practitioners, mental health and addiction specialists, and clients in treatment for SUDs) found that stereotypical beliefs were not different among stakeholders, but attribution beliefs were more diverse. Considering social distance and expectations relating to rehabilitation opportunities, the general public was most pessimistic toward individuals who use substances, followed by general practitioners, mental health and addiction specialists, and clients (Van Boekel et al. Citation2015). A qualitative study of the public stigma of SUDs among four stakeholder groups (current users, former users, family members and service providers) revealed a total of 66 stigma themes related to stereotypes, prejudice and discrimination (Nieweglowski et al. Citation2018). Finally, a questionnaire study among Norwegian adults examined the distribution and role of causal beliefs, inferences of responsibility and the moral emotions relating to deserving help for those with drug problems (Rise et al. Citation2014). Respondents in this study primarily regarded the cause of addictions as residing within the individual, attributed the responsibility of the problem to the individual and considered that those suffering from addiction were not generally viewed sympathetically (Rise et al. Citation2014). It also appears that the process of stigmatization and self-stigmatization may be related to how behaviors are socially constructed (Matthews et al. Citation2017). Having substance use problems, from this perspective, is viewed through historically and socially situated concepts, such as being addicted and experiencing a loss of control. These concepts are imbued with moral values. Taking up a socially constructed and morally loaded addiction identity can be accompanied by stigma and self-stigmatization (Matthews et al. Citation2017) and may have adverse implications for cessation (Wiens and Walker Citation2015). This body of work therefore illustrates that drug use is associated with widespread stigmatization with adverse consequences for those directly affected. However, the focus on this previous work has been on stigma discrediting people with SUDs and it is therefore essential for research more carefully consider how bereaved people close to these individuals may be tarnished by associative stigma.

Social support

Since social support has been shown to be an essential factor in how people bereaved by sudden and unnatural death cope with grief (Dyregrov and Dyregrov Citation2008, Lakey and Orehek Citation2011, Nurullah Citation2012), integration of knowledge from the fields of stigma and grief and social support may be a fruitful means of improving understanding. Extensive research has been conducted into how social network support for psychological problems following adverse events, including sudden and unnatural deaths, may shape bereavement outcomes. Somewhat surprisingly, this research has produced divergent findings in terms of the expected impact of social support on the bereavement process (Dyregrov and Dyregrov Citation2008). In this way, studies in the US and Norway document that, whereas many family members and close friends may be present and supportive shortly after suicides and other unnatural deaths, a large number of bereaved people experienced being avoided by their personal networks (Dyregrov Citation2003, Citation2004, Feigelman et al. Citation2011, Dyregrov et al. Citation2016). Relatedly, Dyregrov (Citation2006) found that the members of social networks primarily withdrew because of their fear of saying or doing something ‘wrong’ when meeting with the person bereaved by such premature deaths.

We propose that the dynamic communicational processes during such encounters are contextually shaped and of the utmost importance to the experiences of those bereaved (Dyregrov and Dyregrov Citation2008, Lakey and Orehek Citation2011). One of the earliest theorists who viewed communication as a reciprocal relationship between different parties was Watzlawick (Watzlawick et al. Citation1967). He asserts that if one accepts that all behaviors/actions mean something for somebody (in other words, these actions are communications), it follows that, regardless of how much you try, ‘you cannot not communicate.’ This perspective implies that both uttering words of empathy and walking away to avoid a bereaved individual constitute communication. Other theorists who follow in this sociocultural tradition similarly emphasize that everything that is communicated has a relational and a content-related message (Bateson Citation1972, Briggs Citation1986). Communicating social support that is adapted and appropriate to the individual and the situation might therefore be associated with manifold challenges (Lakey and Orehek Citation2011, Wright Citation2016). Social support, which is experienced as positive, has at the same time been found to be crucial in dealing with grief after, e.g. suicide, accidents and terror. Bereaved people, in this way, describe the support of friends and family as ‘alpha and omega’, enabling them to carry on with life (Dyregrov and Dyregrov Citation2008, Dyregrov et al. Citation2018). Studies have indicated that individuals with SUDs experience a lack of understanding and stigmatization from society (Lloyd Citation2013, Yang et al. Citation2017). However, there is a knowledge gap relating to how widespread experiences of stigma are for people bereaved by DRDs and whether the content of such communications could be discredited. In other words, the extent to which the stigma attached to the deceased individuals with SUDs may be transferred to their relatives and close friends following their death remains in need of elucidation.

With the above in mind, this study therefore examines the occurrence and content of stigmatization of those bereaved by DRD through addressing the following two research questions. First, we sought to gain an understanding of how many bereaved people experience stigmatizing communications from others and from whom. Second, we gauged who makes negative comments to bereaved people following their loss. Third, we examined the content of the negative communications.

Method

Methodological overview

This article is part of the Drug Death Related Bereavement and Recovery (END) project, which is a Norwegian nationwide, cross-sectional, mixed-methods study. The main objectives of the END project are to explore how those bereaved by a DRD experience grief and stigma, and how they are supported by health and social care services (Dyregrov et al. Citation2021).

Participants

The total sample in END consists of 255 bereaved individuals who have lost a child, parent, sibling, partner, other family member or close friend to a DRD. For characteristics of the 106 participants described below (procedure), see in Results.

Table 1. Characteristics of drug-death bereaved experiencing stigmatizing comments.

Materials

The present data consist of the written answers to one standardized question in the survey which asked, ‘Have others expressed negative attitudes following the drug-related death,’ and which had to be answered with either ‘yes’ or ‘no’. Subsequently, participants who answered in the affirmative were asked to respond to two open questions in the survey in addition to the demographic information. The open questions to be answered with written statements were 1) ‘If anyone has expressed negative attitudes or statements, please specify who’ and 2) ‘What are the worst comments that others have made about the deceased?’ These questions followed other items in the survey that mapped the unique grief and possible stigma of the bereaved individuals. The questions were developed by the researchers in collaboration with four ‘experts by experience’ with personal experience of being bereaved by a DRD.

Responses suggest that 149 (58%) respondents out of the 255 had not experienced derogatory remarks after their loss and that 106 (42%) had experienced negative comments. The 106 respondents who described that others had made negative comments regarding their loss represent the sample for this study (for a description see the results section). All 106 individuals wrote between one and five sentences relating to remarks made by other people, yielding informative qualitative material. The written statements of both open questions were linked to an ID corresponding to the respondent’s background information and exported to a Microsoft Excel matrix for analyses.

Procedure

Participants were recruited through by electronically contacting all Norwegian municipalities, governmental and non-governmental personnel working with drug users and municipal medical officers and crisis responders across the country. The researchers sent information letters to various officials and agencies in contact with DRD services who were asked to pass on information about the survey to people who had been affected by DRDs. The same information was sent to research networks and professionals in clinical practice, participants at addiction conferences and via various media, such as television, radio and social media (Facebook and Twitter). Existing participants also recruited new participants, i.e. via ‘snowball recruitment’ that often is used in research with hidden and vulnerable populations (e.g. Sadler et al. Citation2010).

The participants were invited to complete a questionnaire, either on paper or digitally. All participants signed a written informed consent form that described the study’s purpose, method and procedures. Respondents were informed that the data would be published in a non-identifiable manner. Data utilized here were collected during the period 2018–2019 as part of the END project which consists of an extensive survey with standardized and open questions, and qualitative interviews. The study was approved in February 2018 by The Norwegian Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics (2017/2486/REK vest).

Analyses

Thematic analysis (TA; Braun and Clarke Citation2006) was used to examine the written statements. TA is a method for identifying, analyzing and reporting patterns (themes) within data. It is a flexible approach that can be used across various epistemologies and research questions and is compatible with both essentialist and constructionist paradigms within social sciences. In this study, TA is used as a ‘contextualized’ method, posited between the two poles of essentialism and constructionism. It is influenced by theories such as critical realism (Willig Citation1999), which acknowledge the ways in which individuals make meaning of their experience and, in turn, the ways in which the broader social context impinges on those meanings, while retaining focus on the material and other limits of ‘reality.’ Themes or patterns within data are identified in an inductive or ‘bottom-up’ way, meaning that they are firmly grounded in and linked to the data. The themes are patterns across data sets that are important in describing a phenomenon and are associated with the specific research question. Aware of the fact that analysis always will be shaped by the researchers’ theoretical assumptions, disciplinary knowledge, research training, prior research experiences and personal and political standpoints, inductive TA aims to stay as close as possible to the meanings in the data.

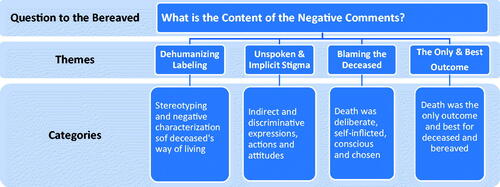

Braun and Clarke (Citation2006) describe a six-phase process for thematic analysis: (1) familiarization with the data; (2) coding; (3) generating initial themes; (4) reviewing themes; (5) defining and naming themes, and (6) writing up. The phases are sequential, each builds on the previous phase and the analysis is therefore a recursive process. As authors, we started reading and re-reading all the written pieces of text to become intimately familiar with their content. Then we coded the entire data set in Excel, examined the codes and collated data to identify significantly broader patterns of meaning (potential themes). Next, initial themes, defined as patterns of shared meanings underpinned by a central concept or idea, were generated. After moving back and forth between the phases, themes were reviewed and decided upon iteratively and given informative names. A figure of codes and themes was produced ().

The analyses were conducted by the first author (Ph.D. sociology) and the second author (Ph.D. social work) individually. Thereafter the authors compared categories and themes and found that we had derived very similar conclusions regarding the contents for categories and themes. Finally, small adjustments were made to create consensus, e.g. to decide on specific names, whether there should be five or four main themes and which quotations should be presented in the article. Both authors agreed upon the coding framework, the interpretation of the data and the decisions of codes and themes.

Results

How many of those bereaved by a DRD experienced negative or stigmatizing comments from others?

The characteristics of the 106 respondents are described in .

Forty-nine percent (N = 52) of the sample had college or university education and 56% (N = 59) were in paid labor. Eighty-six percent (N = 91) reported that they had felt ‘very close’ to the deceased at the time of death. Almost all the respondents (94%) knew about the deceased person’s drug use before their death.

Among the deceased, 27% were women (N = 29) and 73% were men (N = 77), aged between 17 and 68 at the time of death, with a mean age of 33 (SD = 10.847). Their problematic drug use had lasted, on average, for 16 years, with a minimum of one year and a maximum of 42 years before death (SD = 9.558).

The individuals who made negative comments after the loss

Negative comments originated from four groups: 1) close/extended family and friends, 2) work colleagues, neighbors and acquaintances, 3) media, social media and ‘society in general’ and 4) professionals. Many of the respondents (N = 106) reported negative comments from more than one group ().

Table 2. Drug-death bereaved reporting negative comments from different actors (N = 106).

As seen in , as many as 57% of the negative comments derived from close and extended family and friends. The family members included fathers, parents-in-law, ex-partners, grandparents, uncles and aunts, cousins and the extended family of the deceased. Friends who made negative comments about the deceased were both friends of the bereaved and of the deceased, varying with regards to the closeness of relationships. Some former drug-using friends of the deceased were present in this group. More than a quarter of the negative comments came from more distant social connections, such as work colleagues, neighbors and individuals whom the respondents referred to as acquaintances. While seven percent found themselves attacked by coverage of drug-related issues in the media and society in general, only one percent had experienced direct negative comments through social media. A bereaved female family member wrote about the subtle remarks from ‘people in general’ as follows: ‘Others have not made direct, derogatory remarks, but between the lines, I have felt that he is not worth much’ (ID 137). Although representing a small number, eight percent of respondents reported that health personnel and other helpers had hurt them with negative remarks about the deceased or about themselves. Among the specific individuals or groups mentioned were the medical secretary at the doctor’s office, the family doctor, the psychologist, hospital personnel, health personnel in general, the police and the NAV (Norwegian Labor and Welfare Administration).

The content of the negative comments

Four interconnected themes were identified from the data: 1) dehumanizing labeling; 2) unspoken and implicit stigma; 3) blaming the deceased; 4) the only and best outcome ().

Dehumanizing labeling

The most common content of negative comments related to dehumanizing and stereotypical ‘labeling’ of the deceased, mainly represented by one-syllable words or insults. These comments typically contained derogatory remarks positioning individuals who use drugs as non-humans in society. The comments derived from family members, friends and acquaintances who had used disrespectful, strong and rude expressions to denote both the person and the person’s way of life. Several of the respondents experienced the deceased being referred to as ‘such addicts’ or ‘such people,’ i.e. not as an individual, but with generalized and stigmatized group characteristics. Many had heard that their family member or close friend had been stereotyped or regarded as belonging to a stigmatized group, by being called a ‘drug addict,’ ‘junky,’ ‘drug lady’ or ‘drug wreck;’ ‘crook,’ ‘criminal,’ ‘scum’ or ‘trash.’ Certain respondents had been told that the deceased ‘was just a drug addict and did not have a life’ (ID 10) or that ‘she is now a pig in hell’ (ID 88). The negative comments were also related to the characteristics of the deceased, who had been characterized as ‘spoiled,’ ‘selfish,’ ‘weak,’ ‘dishonest,’ ‘false,’ ‘wimpy’ and ‘a coward.’ Other generalizations claimed that the deceased had had ‘a bad personality,’ ‘was an asshole,’ ‘was crazy and not right in the head,’ ‘was silly and easily fooled’ or ‘was an unsuccessful, bad mother,’ often with the originator of the comment not knowing the individual. A mother wrote about what had been said about her 20-year-old deceased daughter:

I was told she was a fucking junky and a fucking whore who had not deserved to live. She should have been taken on the day she was born; she had no right to a life, and she used others’ tax money to get drugs, tricked men into giving her money by selling herself. Girls like that should die (ID 44).

A young woman who had lost a close friend wrote that ‘all the boys in her city had heard about her and knew that if she was given some alcohol, she would throw herself at the boys and give them sex’ (ID 195). As seen from these examples, the descriptions of these individuals were rude, harsh, disrespectful and malicious. Most comments were expressed directly to the bereaved people, said within earshot of them so that they overheard it or were mentioned to others who passed them on. The gross and derogatory descriptions relating to the deceased were challenging to handle and left long-lasting traces among many of those bereaved over several years. The comments prevented them from holding on to the good memories of their child, sibling, parent, partner or good friend. It was also difficult for adults to explain to children why a beloved family member was considered worthless.

As conveyed by one particular family member, the negative comments also indicated to the bereaved that their family member or close friend did not have the right to life: ‘They’ should be given drugs with rat poison so that we got rid of ‘them.’ A mother who fought against the stigma wrote how she had learned to deal with negative comments:

I always try to be one step ahead of the comments by explaining what he experienced as a child (sexual abuse) before people could comment on his drug use. I have experienced that people who get to know the cause of his drug addiction show empathy and understanding on an entirely different level than those who only believe that he used drugs to get high. This has become my strategy both to “defend” why things turned out the way they did and to escape the stigma that surrounds many drug users (ID 25).

Unspoken and implicit stigma

The second theme contained expressions, actions and attitudes that were communicated more indirectly but were still discriminatory. Respondents claimed that hurtful communications came from society because people lack information as to why people use drugs. Some of the following quotations are from pre-death experiences and some from post-death experiences. A Christian told a bereaved individual that her sister would not be received by God because of her drug use (ID 23). Another woman wrote about her worst experience soon after losing her sister, that influenced her grief process:

It is challenging to remember particular episodes, but one thing I remember best is a doctor’s visit she had just before she died. She was distrusted and did not receive the help she needed. They looked at her history and assumed that she was just looking for medication. I went with her to the doctor for the first time because she knew she would not be trusted. She had a chance of being believed if some of those closest to her could witness her pain. The way in which the doctor was talking to her was condescending and I do not believe that they took her seriously in any way (ID 182).

There were many indirect and hurtful communications relating to stigma. Those bereaved by a DRD had experienced people talking about their successful children in front of them and expressing their relief that their children had not been as stupid. Evidence of the ruthlessness of the statements was shared by a mother who was told face to face that ‘There is a bit of a son you have. Probably not many will attend his funeral’ (ID 77).

One sister described how silence and the lack of support were overwhelming on the part of those who had known her sister as a drug user. In contrast, the community which only knew her before her problematic drug use acted quite differently after the death:

I notice an intense silence in the village where I live and have lived for 20 years; only a few comments and one bouquet of flowers afterward. In contrast, the town where we grew up has shown heartfelt care to my father and the people there have made lovely comments to my siblings and me. They had known my sister for many years and knew what a wonderful person she was before the intoxication destroyed her over the last three years (ID 138).

The examples above are indications that lack of social support might result from stigma and disgrace, affecting the prospects of adaptive healing from grief.

Blaming the deceased

The third theme relates to comments that attribute the guilt and responsibility to the deceased. The magnitude of this third theme was overwhelming. Once again, many of the harsh comments originated from people both close and more distant to the respondents. The content of such messages centered on the death being self-inflicted, conscious and chosen. Many of those around the bereaved had ‘waited for the death to come.’ One sister who had worked hard to avoid blaming herself for the death of her younger sister wrote how the comments of others negatively affected her in her time of grief:

It was not right when my GP told me that “everyone is the maker of their own fortune.” He probably meant to console me, that I should not take responsibility for my sister’s suicide and that I could not save her from drug use. However, I did not feel good about hearing this. I cannot stand to listen to others’ comments that can be interpreted as blaming her for her misery…I am also very aware of how people in similar situations are referred to and are easily hurt. During these difficult years, I have worked hard to orient myself to reality and to place the responsibility on her instead of myself, but I cannot stand to hear this from others (ID 138).

Many of the bereaved had heard that the problematic drug use was ‘self-inflicted’ and had to end like this, e.g. ‘He used his own hands to die’ (ID 23). From the point of view of many individuals passing comment, the deceased had decided to live as they did (ID 90). They claimed that the drug user had not wanted to be freed from drugs; it was a deliberate act and a life they had chosen, e.g. ‘It was a choice she made, so it was her fault’ (ID 125). A mother was told by her work colleagues that ‘her son had only himself to blame, as he had never managed to get clean’ (ID 2). People were sure that the deceased could have lived a drug-free life, if only they were willing to do so.

The perception that substance use problems are deliberate and chosen was spelled out in a message to a bereaved sister who had lost her brother: ‘He made his choices and suffered the consequences’ (ID 122). A woman who had lost her mother was told that ‘She [the mother] deliberately ruined the lives of my father and us children on purpose’ (ID 129). The deceased were not only blamed after death; one family member was told that ‘they should also feel guilty while alive’ (ID 73).

Underpinning many of the statements appeared to be a deterministic notion that problematic drug use leads to death and that there is no other way out. Therefore, as the deceased were drug addicts, they ought to have been prepared for death. Certain individuals told this bereaved sister, ‘He knew what he was doing, so we knew that this would happen..’ (ID 23). Based on such assumptions, some people even concluded that ‘the death could not be such a big deal as he had not wanted to help himself’ (ID 184).

The only and the best outcome

The fourth theme contained statements that the death of the substance user was the only and the best outcome, i.e. best for the deceased and best for those left behind. Implicit in the statements was that there was no hope for rescue for ‘such lives’. Typical examples of statements in this theme were: ‘It was probably best that he was released’ (ID 25) and ‘It was probably best that he died’ (ID 57). Other comments were that ‘She is better off now than she was’ (ID 90), ‘You were lucky to have been spared any further anguish when he died’ (ID 77) and ‘What happened [the death] was best for all parties’ (ID 149).

The theme contains statements that were perhaps intended to comfort and to show care toward the deceased and the bereaved, cf. ‘He is better now, and you are better now’ (ID 69). Seemingly, however, the message content was interpreted as the deceased being spared a great deal of pain and the bereaved being spared the burden of looking after their family member. Hints relating to the deceased causing the bereaved pain were both implicit and explicit. A mother was told that it was best that he [her son] died, so that she knew where he was (ID 84) and a recently bereaved sibling was told that ‘You should be glad he is dead because now you have no trouble with him anymore’ (ID 154).

Comments relating to death as being the best outcome conveyed the perception that death was the only way out of a difficult situation. A mother was told that ‘her son would never be drug-free and that they should have been prepared for the death’ (ID 14). It was challenging and hurtful for respondents to hear that death was the best outcome, and they wondered how other people could possibly know whether or not this was best. They also experienced that such statements were an expression of their judgment of someone’s life. A mother (ID 82) who lost her child two years previously explained why questions such as ‘Maybe it was for the best,’ ‘What kind of life would he have had?’ and ‘Are you relieved?’ had caused her a great deal of stress during her grieving process:

Who can judge his life? His dreams, his hopes, his struggle to succeed, his value as a human being. He was so incredibly nice and cared for those around him even when he was struggling. He also made good and positive choices himself without those who loved him insisting on these choices. He is so important to us who love and loved him. That he should be less valued as a human being because he was addicted to drugs, hurts so much. That his loss of life and his death should have less value because he was also addicted to drugs, is so painful (ID 82).

Some of the statements signaling that death was the best outcome also contained a degree of condemnation, as one medical secretary stated, ‘His life was ruined anyway’ (ID 46). Other bereaved individuals had heard comments that the deceased had no quality of life and was ‘only garbage’ anyway – so death was the best outcome and was deserved.

As a result of statements indicating that the deceased did not deserve to live and actually made the life of the bereaved better by dying, many of those bereaved could probably relate to one mother, who stated, ‘Maybe people don’t think we are grieving since he was just a drug addict’ (ID 227).

Discussion

Findings from the present study show that those bereaved by a DRD heard numerous, harsh comments that were challenging to deal with in the wake of losing a beloved son, daughter, mother, father, sibling or close friend. They underscore the value of examining what Sheehan and Corrigan (Citation2020) conceptualized as associative stigma and demonstrate how stigma associated with a loved one’s substance use can influence and complicate the bereavement processes. This discussion reflects on how the results relate to previous research on stigma and SUDs, research on grief and social support, and highlight implications of the current study.

Context and basis for the comments

The comments that the bereaved respondents received mirrored the culturally simplified stereotypes relating to people with SUDs highlighted in other studies (e.g. Schomerus et al. Citation2011, Van Boekel et al. Citation2013, Yang et al. Citation2017). Our findings reflect that the stereotypes apply to both cultural perceptions that drug use relates to moral weakness and that drug users are individuals with specific discredited characteristics (Matthews et al. Citation2017, Atayde et al. Citation2021). Furthermore, the analysis shows that the comments are based to a large degree on resignation and that those individuals making the comments have little faith in those with SUDs being able to solve their problems with death, therefore, being the only solution. Drug use behavior is also associated with several other contexts that may be stigmatized, such as crime, prostitution, violence and manipulation, which provide a further breeding ground for stigmatizing comments. Thus, fear and anxiety of unknown and frightening phenomena related to drug use also contribute to the condemnation, conveyed through people’s comments and attitudes. Finally, our analysis reflects the self-stigma reported by Corrigan and Rao (Citation2012) that follows from the comments that the curse and stigma related to the drug users are transferred to those bereaved by a DRD following the drug user’s death.

Noting that structural stigma is linked to cultural norms (Hatzenbuehler and Link 2014), our findings therefore reflect how communications presented in this study are embedded in wider social-cultural contexts (Watzlawick et al. 1967, Bateson Citation1972, Dyregrov and Dyregrov Citation2008). In this way, whether the encounter is experienced as supportive, non-supportive, indifferent, harmful or insulting, depends on the receivers’ (i.e. the bereaved individual) interpretations of the encounter. As such, the frames for interpreting the types of social interaction, the goal of the interaction, social roles, the social situation, the form of the message, the communication channel and the linguistic messages are situated and must be understood in the specific social-cultural context. One implication of this is that expressions which may be considered very rude in one culture may be regarded as less rude in another. We are confident that we may consider the communicative intent to be stigmatizing, because of the directness, severity and maliciousness of the comments cited by those bereaved by a DRD. Our findings therefore indicate that socialization in the Norwegian cultural context, as probably in many other cultural contexts, still leads to harsh stigmatization of individuals with SUDs. As seen from our results, and as Goffman (Citation1963) highlighted, these devaluation norms are conveyed by means of attitudes and language to bereaved people.

Stigma and social support

Furthermore, the comments that the bereaved respondents received also show that the stigmatization and devaluation of people with SUDs also seem to influence the social support offered to people bereaved by a DRD. From this perspective, the communications identified in this study are beyond common social behavior and must be related to the mode of death, i.e. death due to a stigmatized way of life within the current Norwegian social setting. Our findings differ from previous research that has found that members of social networks of those bereaved by other unexpected deaths (e.g. Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) or accidents), are afraid of being importunate and struggle to find a suitable level of intensity for their efforts and appropriate forms of expression for their support (Dyregrov and Dyregrov Citation2008). Whereas members of informal networks are usually uncertain as to whether they may have said or done something wrong (Dyregrov Citation2003, Citation2004, Dyregrov and Dyregrov Citation2008), our findings reflect that many family members and close friends seem to deviate from such expected behavior. In the following, we discuss how stigma may influence several key aspects of social support and bereavement processes.

Even though many family members and close friends had possibly been living under a great deal of stress and may have anticipated death, they might also experience conflicting feelings of grief, anger, guilt, self-blame and relief post-loss (da Silva et al. Citation2007). They feel guilt for not managing to prevent the death and about feeling relief that the drug user is dead. Feeling relief about another person’s death is widely regarded as being outside society’s norms. At the same time, the feeling of relief can displace feelings of grief and sadness. This conflict may complicate the bereavement process and people may struggle more after a DRD than after death from other causes. Templeton et al. (Citation2017) highlight that relatives often have feelings of shame and guilt for not doing more to help and for the emergence of the drug problem in the first place. In this vein, our findings relating to comments implying that death was self-inflicted may heighten bereaved people’s feelings that grieving over the deceased is not legitimate which may undermine the grieving process. In a study of those bereaved by drug and alcohol deaths, Templeton et al. (Citation2017) documented that lack of understanding and empathy were among the factors that worsened the grief. Our findings reflect that the grieving process may be negatively affected by harsh, stigmatizing, guilt-provoking comments.

Our findings highlight how bereaved by DRDs who experience disgraceful and harsh communications about their deceased may be haunted by adverse consequences of stigmatization. First and foremost, they may experience persistent and great shame and guilt. The American psychologist Janina Fisher (Citation2017), who has studied how shame interferes with traumatic experiences, maintains that the persistence of shame poses a barrier to healthy grieving. She emphasizes that self-alienation can only be maintained by most individuals at the cost of increasingly greater self-loathing, disconnection from emotion, addictive or self-destructive behavior, and internal struggles between vulnerability and control (2017). Those who struggle with chronic shame may experience this feeling even during positive experiences, such as receiving praise or applause. Shame also slows down anger and makes us give in and not think clearly (Fisher Citation2017). Despite full participation in life, as was the case for most all in our sample, pleasure and spontaneity, healthy self-esteem can be counteracted by recurrent shame. Also, in line with Curcio and Corboy (2020), the internalization of shame may worsen bereaved by DRDs problems and reduce treatment adherence and response.

Our findings relating to the comments that attributed the blame and responsibility of the death to the deceased further document widespread feelings of guilt among the bereaved. When Li et al. (Citation2019) investigated the relationship between bereaved individuals’ guilt and well-being, they found that a higher level of guilt predicted complicated grief and depression symptoms one year later. They also found that responsibility guilt, indebtedness guilt and the degree of guilty feelings were prominent aspects of guilt in complicated grief. These findings demonstrate the significant role of guilt (perhaps a core symptom) among the mental health of bereaved people, having implications for individuals experiencing condemnation and stigmatization from the surroundings, such as those bereaved by a DRD. As seen in the present study, when grief is not acknowledged because it is stigmatized and when there is a high level of general stress combined with social isolation among the bereaved, this may increase the risk of developing Prolonged Grief Disorder.

Finally, the current study indicates that stigmatization can affect the interplay and communication between those bereaved by DRDs and employees in the health service, which adds to the burden of the bereaved. A bereaved person will often withdraw from family and friends who utter negative and disgraceful comments as presented in this study. In a nationwide study of those bereaved as a result of suicide, accidents and SIDS, Dyregrov et al. (Citation2003) found that (self) isolation was the main predictor of prolonged/complicated grief reactions, general psychological health and trauma reactions. Thus, a lack of social support may increase the possibility of isolation among those bereaved by a DRD and, as such, may increase the possibility of more health and social challenges. Therefore, knowledge of the processes and effects of self-stigmatization and stigmatization, is essential for both the wider social networks of individuals affected and their helpers.

Implications

A key finding in our study is that a significant group of people bereaved by DRDs experience associative stigma that, to a greater or lesser extent, reflects existing societal stigma toward drug users. One implication is the need for interventions to reduce SUD stigma. A systematic review of stigmatization by health professionals relating to individuals with SUDs points to the positive effect supervision and training can have on professionals’ attitudes in healthcare delivery (Van Boekel et al. Citation2013). A systematic review of the effectiveness of interventions for reducing SUD stigma found a range of interventions promising to deliver meaningful improvements with regard to the stigma surrounding SUD, e.g. reducing self-stigma through therapeutic interventions such as group-based acceptance, addressing social stigma by communicating positive stories of people with SUD and reducing the stigma from the perspective of professionals by means of educational programs (Livingston et al. Citation2012). However, these authors cautioned that a small body of research prevented them from making conclusive remarks. To this end, the current study adds new knowledge about the magnitude and content of stigmatizing communication reaching those bereaved by DRD, to inform therapeutic interventions to fight the stigma imposed on this group of bereaved.

A second implication of our findings is that members of the social network (family, friends, work colleagues and neighbors) need to be educated on the hurtful consequences of stigmatizing communication with individuals bereaved by a DRD and to overcome their uncertainties in relation to supportive communication. This study contributes to this education by documenting and making the occurrence and content of stigmatization toward those bereaved by a DRD more visible. The focus of the study is on the complex societal phenomenon of stigma. However, as the open question in our study addressed also interpersonal stigmatization, there is also a need for future research to carry out a more in-depth exploration of intrapersonal and societal stigmatization and the relationship between all three levels of stigma.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of the present study is the sample size (N = 255 respondents bereaved by DRD), which to our knowledge is the most extensive study conducted with this group. It provides a valuable starting point to examine the occurrence and content of stigmatization of those bereaved by DRD. Still, despite our efforts to recruit people from all social classes, the risk of sampling bias was present, particularly given that people from lower social classes are underrepresented. Further, although deriving from the world’s largest sample of people bereaved by DRD, the quantitative results are based on many subgroups with a relatively small number of individuals in each group. The generalizations from the quantitative data should therefore be handled with caution.

To increase the credibility of the analytic results we have presented the study with a high degree of transparency. To make explicit potential blind spots of each researcher, the two authors analyzed the data separately, then discussed the categories and the themes to yield the most ‘credible’ conceptual interpretation of the data. Moreover, transparency was highlighted by referring to respondent IDs when presenting the quotations that exemplify the themes. As such, since the data are based on the written experiences of a large and varied community of individuals bereaved by DRDs, the findings may be applicable and transferable beyond the project. Finally, in line with Lincoln and Guba (Citation1985), we consider the data analysis and theory generation to be reliable, as it has been completed by two senior researchers, representing the fields of both bereavement and substance use problems.

Conclusion

In this study, we have revealed that those bereaved by a DRD face many forms of stigmatization from family, friends, professionals and from society in general. Direct and indirect stigmatizing communications consist of dehumanizing labeling, unspoken and implicit stigma, blaming the deceased and claiming that death was the best and only possible outcome. Such communications were disgraceful and harsh, and contributed to marginalizing a group of grieving individuals who required support rather than being ostracized. Making people aware that stigma exists, increasing knowledge as to why it occurs and how it is transmitted in society can help remove the stigma.

Acknowledgements

We heartily will thank all the bereaved who have used their time and energy to participate in the END research project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Atayde AMP, Hauc SC, Bessette LG, Danckers H, Saitz R. 2021. Changing the narrative: a call to end stigmatizing terminology related to substance use disorders. Addict Res Theory. 1–4. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/16066359.2021.1875215.

- Bateson G. 1972. Steps to an ecology of mind. NY: Chandler Publishing Company.

- Braun V, Clarke V. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 3(2):77–101.

- Briggs CL. 1986. Learning how to ask. A sociolinguistic appraisal of the role of the interview in social science research. NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Corrigan PW, Rao D. 2012. On the self-stigma of mental illness: stages, disclosure, and strategies for change. Can J Psychiatry. 57(8):464–469. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371205700804. 22854028

- Corrigan PW, Watson AC. 2002. The paradox of self-stigma and mental illness. Clin Psychol. 9(1):35–53.

- Curcio C, Corboy D. 2020. Stigma and anxiety disorders: a systematic review. Stigma Health. 5(2):125–137.

- Da Silva EA, Noto AR, Formigoni MLOS. 2007. Death by drug overdose: impact on families. J Psychoactive Drugs. 39(3):301–306.

- Dyregrov K. 2004. Micro-sociological analysis of social support following traumatic bereavement: unhelpful and avoidant responses from the community. Omega. 48(1):23–44.

- Dyregrov K. 2006. Experiences of social networks supporting traumatically bereaved. Omega. 52(4):339–356.

- Dyregrov K, Dyregrov A. 2008. Effective grief and bereavement support: the role of family, friends, colleagues, schools and support professionals. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Dyregrov K, Dyregrov A, Kristensen P. 2016. In what ways do bereaved parents after terror go on with their lives, and what seems to inhibit or promote adaptation during their grieving process? A qualitative study. Omega. 73(4):374–399.

- Dyregrov K, Kristensen P, Dyregrov A. 2018. A relational perspective on social support between bereaved and their networks after terror: a qualitative study. Glob Qual Nurs Res. 5:2333393618792076–2333393618792012.

- Dyregrov K, Nordanger D, Dyregrov A. 2003. Predictors of psychosocial distress after suicide, SIDS and accidents. Death Stud. 27(2):143–165.

- Dyregrov K, Titlestad KB, Løseth H-M. 2021. ResearchGate. The END-project. https://www.researchgate.net/project/DRUG-DEATH-RELATED-BEREAVEMENT-AND-RECOVERY-The-END-project.

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. 2019, March. European drug report 2019: trends and developments.

- Feigelman W, Jordan J, Gorman B. 2011. Parental grief after a child's drug death compared to other death causes: investigating a greatly neglected bereavement population. OMEGA. 63(4):291–316.

- Fisher J. 2017. Healing the fragmented selves of trauma survivors. Overcoming internal self-alienation. NY, USA and London: Routledge.

- Goffman E. 1963. Stigma. Notes of the management of spoiled identity. NY: Penguin Psychology.

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Link BG. 2014. Introduction to the special issue on structural stigma and health. Soc Sci Med. 103:1–6.

- Henderson C, Gronholm PC. 2018. Mental health related stigma as a ‘wicked problem’: the need to address stigma and consider the consequences. IJERPH. 15(6):1158.

- Lakey B, Orehek E. 2011. Relational regulation theory: a new approach to explain the link between perceived social support and mental health. Psychol Rev. 118(3):482–495.

- Li J, Tendeiro JN, Stroebe M. 2019. Guilt in bereavement: its relationship with complicated grief and depression. Int J Psychol. 54(4):454–461.

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. 1985. Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park (CA): Sage Publications.

- Link BG, Phelan JC. 2001. Conceptualizing stigma. Annu Rev Sociol. 27(1):363–385.

- Livingston JD. 2013. Mental illness-related structural stigma. The downward spiral of systemic exclusion. Mental Health Commission of Canada. www.mentalhealthcommission.ca.

- Livingston JD, Milne T, Fang ML, Amari E. 2012. The effectiveness of interventions for reducing stigma related to substance use disorders: a systematic review. Addiction. 107(1):39–50.

- Lloyd C. 2013. The stigmatization of problem drug users: a narrative literature review. Drugs. 20(2):85–95.

- Matthews S, Dwyer R, Snoek A. 2017. Stigma and self-stigma in addiction. J Bioeth Inq. 14(2):275–286.

- Nieweglowski K, Corrigan PW, Tyas T, Tooley A, Dubke R, Lara J, Washington L, Sayer J, & Sheehan L. 2018. Exploring the public stigma of substance use disorder through community-based participatory research. Addict Res Theory. 26(4):323–329.

- Nurullah AS. 2012. Received and provided social support: a review of current evidence and future directions. Am J Health Stud. 27(3):173–188.

- Rise J, Aarø LE, Halkjelsvik T, Kovac VB. 2014. The distribution and role of causal beliefs, inferences of responsibility, and moral emotions on willingness to help addicts among Norwegian adults. Addict Res Theory. 22(2):117–125.

- Sadler GR, Lee H-C, Lim RS-H, Fullerton J. 2010. Research article: recruitment of hard-to-reach population subgroups via adaptations of the snowball sampling strategy. Nurs Health Sci. 12(3):369–374.

- Sheehan L, Corrigan P. 2020. Stigma of disease and its impact on health. In: The Wiley encyclopedia of health psychology. p. 57–65. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119057840.

- Schomerus G, Lucht M, Holzinger A, Matschinger H, Carta MG, Angermeyer MC. 2011. The stigma of alcohol dependence compared with other mental disorders: a review of population studies. Alcohol Alcohol. 46(2):105–112.

- Stroebe M, Schut H, van den Bout J. 2012. Complicated grief: scientific foundations for health care professionals. London and New York: Routledge.

- Templeton L, Valentine C, McKell J, Ford A, Velleman R, Walter T, Hollywood J. 2017. Bereavement following a fatal overdose: the experiences of adults in England and Scotland. Drugs Educ Prev Pol. 24(1):58–66.

- Titlestad KB, Lindeman SK, Lund H, Dyregrov K. 2019. How do family members experience drug death bereavement? A systematic review of the literature. Death Stud. 1–14. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2019.1649085.

- Van Boekel LC, Brouwers EP, Van Weeghel J, Garretsen HF. 2013. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 131(1–2):23–35.

- Van Boekel LC, Brouwers EP, van Weeghel J, Garretsen HF. 2015. Comparing stigmatising attitudes towards people with substance use disorders between the general public, GPs, mental health and addiction specialists and clients. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 61(6):539–549.

- Watzlawick P, Beavin J, Jackson D. 1967. Pragmatics of human communication. USA: W.W. Norton & Company Inc.

- Wiens TK, Walker LJ. 2015. The chronic disease concept of addiction: helpful or harmful? Addict Res Theory. 23(4):309–321.

- Willig C. 1999. Beyond appearances: a critical realist approach to social constructionist work. In: Nightingale DJ, Cromby J, editors. Social constructionist psychology. Buckingham/Philadelphia (PA): Open University Press; p. 37–51.

- Wright K. 2016. Social networks, interpersonal social support, and health outcomes: a health communication perspective. Front Commun. 1:10.

- Yang L, Wong LY, Grivel MM, Hasin DS. 2017. Stigma and substance use disorders: an international phenomenon. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 30(5):378–388.