Abstract

Sports are criticised for their lack of social and political responsibility. In this study, I ask people about the extent to which they think it is important that sports should be sociopolitically responsible regarding ten issues: health, social communities, gender, racism, integration of minorities, sexual orientation, social inequality, disabilities, doping, and the environment. Next, I investigate how people’s opinions vary according to their social backgrounds, affiliation with sports, and political party voting. The study is based on a survey of a representative sample of Norwegians (N = 1,131, age 18–79, response rate 26%). I analyse data using simple relative frequencies and logistic regression models. I build a theoretical framework based on various issues’ closeness to sports’ and how politically contested they are. I found that many Norwegians think it is ‘very important’ for sports to be sociopolitically responsible − 80% (most) saying this for doping and 47% (least) doing so for the environment. Women demand more sociopolitical responsibility for sports than men, and those affiliated with sports state that health and social relations should be issues for sports and political orientations influence the view on politically contested issues. The support for sports being sociopolitically responsible could indicate a potential for sports to be involved in social and political issues. How sports organisations meet these challenges will influence sports’ capacity to recruit volunteers, political legitimacy, and ability to attract commercial sponsors.

Introduction

Something is rotten in the world of sports: Too much money and greed, not enough social and political responsibility (Chen, Citation2022; Fruh et al., Citation2022; Houlihan, Citation2022; Wagner & Storm, Citation2022). Globally, corrupt totalitarian regimes use sports for ‘sports washing’ (Boykoff, Citation2022; L. Davis et al., Citation2023).Footnote1 Locally, sports are accused of racism, homophobia, and gender discrimination (IWG, Citation2018).Footnote2 Sports are seen as lacking concern for environmental issues (Gammelsæter & Loland, Citation2023; Sandvik & Seippel, Citation2022), and there is a never-ending stream of news on doping and cheating (Harris et al., Citation2021; Pielke, Citation2016). On top of that, ever-increasing costs lead to differences in sports participation based on social class (P. L. Andersen & Bakken, Citation2018).

At the same time, there are also signs of socially and politically responsible sports (Verschuuren & Ohl, Citation2023). Internationally, the UN supports ‘Sports for Climate Action,’ and the International Olympic Committee (IOC) aims for the Olympic Games to become ‘climate positive’ by 2030 (IOC, Citation2021).Footnote3 WADA addresses doping in sports. Athletes make stands on human rights issues and address racism (Nepstad & Kenney, Citation2018), and fans protest the unacceptable actions of club owners (Fitzpatrick & Hoey, Citation2022).

In short, sports operate in two separate worlds: in one world, reckless, escalating, juggernaut sports without normative limits; in the other world, sports aware of and concerned with their social and political responsibilities. An interesting question arises about what people generally think about sports’ sociopolitical responsibilities: Should sports be concerned with sociopolitical issues and, if so, with what issues?

Few studies have directly addressed this question, but people’s opinions on sports’ sociopolitical responsibilities matter. First, because sports involve people, and people’s views are decisive for sports’ ability both to organise sports activities and address social and political issues. Second, athletes are role models (Alrababa’h et al., Citation2021). Third, sports are part of a larger world in which people’s views on sports affect sports themselves: sports depend on volunteers, and the recruitment and retention of volunteers depend on people’s confidence in sports’ abilities to respond appropriately to social and political issues; sports depend on public funding, and sports’ political legitimacy depends on how sports’ responses to the socio-political issues resonate with the public; commercial sponsors are essential in both elite and grassroots sports, and sports’ attraction as sponsorship objects depends on their sociopolitical branding.

In a broader context, an increased politicisation of sports reflects an overall dilemma in modern sports. On the one hand, the modernisation, intensification and sportification of sports imply specialisation, bureaucratisation, scientification, quantification, and a persistent quest for records (Guttmann, Citation1978). The result is modern sports operating on narrow instrumental sports-specific premises, which tend to end up with what Habermas (Citation1987, Citation1996) describes as systems (markets and bureaucracies) colonising the life-world (sports as civil society). Normative concerns lose out to instrumental interest, where sports tend to bow under the weight of commercial and professional claims and demands (Gammelsæter & Loland, Citation2023; Ibsen & Seippel, Citation2010; Lasch, Citation2010; Morgan, Citation1994). On the other hand, civil society react to this development, and several actors stand up for normative and socio-political aspects related to sports. Studying whether and how modern sports are seen as a relevant socio-political force by ordinary people could tell us something about sports’ potential as a civil society force to respond to and counteract modern sports’ narrow sportification processes (Woods, Citation2022).

In this study, I investigate how people perceive sports’ social and political responsibilities. For which social and political issues do they see sports as relevant and consequential actors? Is there a difference between what the general public and people affiliated with sports organisations think of sports’ social and political responsibilities? Are there specific social groups, in terms of age, gender, and education, that expect more responsibility from sports than others? How are positions on sports’ social and political responsibilities linked to conventional political party voting? What do people’s views on sports tell us about the development of sports in general?

To answer these questions, I first present the Norwegian case, look at previous research and sketch a theoretical framework helpful in understanding people’s views on sports’ sociopolitical responsibilities. Next, I present data and methods before providing an overview of the results. First, I show how people consider sports’ social and political responsibilities and how these general views depend on affiliation to sports, political orientations and social background. Second, I investigate views on specific problem issues and also how these correlate to social backgrounds. Finally, I discuss the implications of the results for sports development in a broader perspective: Are we witnessing a further intensification of sports’ modernisation (sportification), or do we observe sports willing to take on socio-political issues and more non-sports responsibilities?

Context and issues

I study people’s opinions on ‘Norwegian Sport Federation (NIF) and Norwegian sports clubs’. Voluntary organisations organise sports in Norway, and there are about 9,500 sports clubs associated with The Norwegian Olympic and Paralympic Committee and Confederation of Sports (NIF). We find clubs within regional sports federations and national sports associations, all under the NIF umbrella. Clubs, with the support of NIF, sports associations and regional confederations, organise grassroots sports, whereas NIF, sports associations and regional federations are also responsible for national and international sports politics. Consequently, most of sports’ political responsibilities – from the grassroots to the international level – are placed in one organisation (NIF).

Volunteers are a vital resource for sports clubs, but public authorities also have significant financial involvement. In 2021, 93% of Norwegian young people claimed, at some time in their lives, to have been members of sports clubs (Bakken, Citation2019); 16% reported that they had volunteered in sports; and 20% asserted that they were a member of a sports club (FrivillighetNorge, Citation2021). In summary, the Norwegian sports system involves large parts of society, and many people have experiences with and opinions on organised sports.

Whether and how sports should be political is contested (Cashmore et al., Citation2023; Grix, Citation2016; Jedlicka et al., Citation2020; Meeuwsen & Kreft, Citation2023; Thiel et al., Citation2017). In this study, I started from the premise that sports are relevant to, involved in, and depend on politics, whether one likes it or not. From a theoretical perspective, sports inevitably build on and comprise contentious issues that involve power and political conflicts (Seippel et al., Citation2018). In practical terms, sports are political because most modern nations have specific sports policies promoting sports for different groups and for various reasons or addressing some of the more current problems facing modern sports (Bergsgard et al., Citation2007; Chalip et al., Citation1996; Scheerder et al., Citation2017). Many nations also have one or more umbrella organisations representing sports clubs’ interests to public authorities and commercial entities (Breuer et al., Citation2015; Citation2017).

To examine how people view sports’ sociopolitical responsibilities, I focused on ten socio-political issues. I selected issues both based on global topics with relevance for our times (Acemoglu, Citation2012; Pinker, Citation2018) and issues that are more local and sports-specific (Gammelsæter & Loland, Citation2023; Grix, Citation2016). The issues are health, social communities, gender, racism, the integration of minorities, sexual orientation, social inequality, disabilities, doping, and the environment (see Data and Methods section).

Previous research and theoretical framework: the framing of problem issues

I ask three questions: To what extent do people think sports, in general, should take social and political responsibilities? How do people rate sports socio-political responsibilities for more specific issues? How do different groups of people attach socio-political importance to sports? To interpret our empirical results, I find guidance in previous research and a theoretical framework based on framing analysis. I use empirical research to make general assumptions about how people see sports social and political responsibilities, and resort to a theoretical framework for beliefs on how different groups of people approach specific issues.

Framing theory

To understand how people claim or expect socio-political responsibilities from sports concerning different issues, I need a theory of how issues are given political meaning and how such meanings function in a larger societal context. Cultural framing is such a theory (Benford & Snow, Citation2000) and builds upon three pillars. First, the theory addresses how various issues activate diagnoses: What are the problems? Second, it asks how issues lead to prognoses: What are the solutions. Finally, one looks at how frames eventually motivate attention and action. As an example, racism is a pertinent problem in sports. Sports should develop solutions (become more inclusive) to the problem, and the problem and solution could motivate attention and action. More dynamically, framing theories make it possible to show how political attention (and eventually mobilisation) occurs by aligning, bridging and extending ideational elements between various frames or so-called master frames (Benford & Snow, Citation2000). For example, feminism and environmentalism could align and reciprocally support each other in the shadow of a left-liberal master frame.

General interest

I found little research directly addressing the topic of this study. I know, however, of three studies on what people think of sports’ social and political potentials. From the findings in these studies, I tentatively sketch some assumptions on how people see it as more or less important for sports to take on socio-political responsibilities.

A first study (E. Davis & Knoester, Citation2020) starts from what Coakley (Citation2015) calls the “Great Sport Myth”. The point is that most Americans see sports as “enjoyable and transformational”, and, according to Coakley, they rather uncritically assume that sports pass “on its inherent benefits unto all who engage in it”. E. Davis and Knoester (Citation2020:29) find empirical support for Americans belief in this myth: “Overwhelmingly, Americans believe that sports participation builds character, improves health outcomes, promotes academic achievement, boosts one’s popularity in school, and makes one more well-known in a community”. A second study (Seippel, Citation2019) looks into how people consider sports’ ability to fulfil three social functions (socialisation, integration and internationalisation), and the findings are positive in much the same way. Third, Meier et al. (Citation2023) study how people react to famous athletes taking political stands. They find that people are positive about athletes’ political activism as long as it is not too controversial, and for more contentious issues, support depends on the political views of the respondents.

In short, people tend to see sports’ potentials and frame sports as solutions to a wide spectre of social problems, and, accordingly, I find it reasonable to hypothesise that many people also think that sports, as long as issues are not too contested, should take socio-political responsibilities (H1). E. Davis and Knoester (Citation2020), Seippel (Citation2019) and Meier et al. (Citation2023) all differentiate between what kinds of problems people might think sports could address. What the studies have in common is that people have stronger beliefs in sports addressing more concrete and less controversial personal-relation issues at a micro level (e.g. personal development, socialisation and integration) than political-structural issues on a macro level (e.g. internationalisation). From this, I infer and hypothesise that personal-relational problems, e.g. health and social relations, are more frequently listed as issues sports should take responsibility for than more political-structural issues as environmental problems (H2).

Specific problem issues

To set up assumptions about what various groups of people think about sports socio-political responsibilities and to study how these views vary across problem issues, I develop a theoretical framework consisting of two parts.

First, to investigate how people frame the socio-political responsibilities of sports, it makes sense to distinguish between three sources of variation in people’s opinions: (i) involvement in sports, (ii) political orientations and (iii) social background. Second, to link these three sources of variation in people’s opinions to the specific problem issues, I categorise problem issues according to how they are (i) relevant for those involved in sports, (ii) for how they are relevant for political orientations and (iii) how they relate to social background variables.

Combining these explanatory factors (how various people tend to frame sports differently) with issue characteristics (how do problem-issues invite different political frames) I formulate a selection of hypotheses for how multiple groups of people approach different problem issues related to sports.

Involvement in sports & problem issues relevant to sports

Those involved in sports face a dilemma when it comes to assessing sports socio-political responsibilities. On the one hand I assume, as for the general population, that athletes have high thoughts about sports’ capacity to solve socio-political problems and, accordingly, think sports should take on a responsibility. On the other hand, they could also feel that (their beloved) sports would suffer if they take on (too many) socio-political responsibilities.

To grasp this dilemma, it makes sense to distinguish between socio-political issues that are close (or intrinsic) to sports’ core activities (e.g. physical health) and issues that are more distant from (or extrinsic to) ordinary sports activities (e.g. solving environmental problems). The tension between issues close/distant to sports could play out in two ideal-typical ways. First, it is easy to take and ascribe responsibility for close-to-sports-problem-issues because the costs for solving such problems are low (e.g. most sports are relatively healthy anyway), and the consequences for taking on the responsibility are minor (the quality of the activity is not changed by being healthy). Second, when it is costly to take responsibility for a problem-issue (football facilities need more environmentally friendly surfaces) and the consequences are high (lower quality surfaces), it becomes more difficult for sports to take on socio-political responsibilities.

Problem issues could then be placed at a spectre from some issues being “close” to sports to others being “distant” from sports. I suggest that sports as a solution to ‘public health’ problems and ‘community issues’ are the best examples of issues close to sports. Addressing and solving them have low costs and few consequences for those involved. On the other end of the spectrum, I find problem issues having higher costs and consequence to address for those interested in sports. The most obvious example is environmental problems, which both could be costly and have (negative) implications for the sports experience.

Hence, I hypothesise that those affiliated with sports would be more than averagely motivated to claim that it is essential for sports to take responsibilities with respect to close-to-sports-issues. In contrast, they will be more hesitant to take on issues “far from sports” (H3).

Political orientations & politically contested problem-issues

I operationalise political orientations through political party voting. It is timely to note that sports seldom have been a salient or significant issue in Norwegian party politics (Bergsgard & Rommetvedt, Citation2006), so to the extent political orientations matter, it will probably be indirectly by problem issues relevant for political parties. This can happen in two (interacting) ways: political orientations can operate at an abstract ideological level and, more specifically for each problem issue.

On the overall ideological level, political parties have ideas of what a good society consists of and principled opinions on social institutions’ responsibilities for societal development and social change. Left-leaning parties favour collective action and public policies. Rightist parties have a stronger belief in market solutions, and some, based on (radical) libertarian and populist political impulses, are sceptical of collective and public solutions. This leaves us with two assumptions and one hypothesis regarding political influences: either collective leftist orientations translate into a taste for collective solutions (through sports as civil society actors), or libertarian-populist scepticism towards collective responsibilities of any kind makes them shy away from attempts to assign sociopolitical responsibilities to sports organisations (H4).

Since many of the problem issues suggested as sports-relevant are also common political issues, I expected people’s political orientations to affect how they consider sports’ sociopolitical responsibilities for specific problem issues – if you are concerned with racism in general, you will also be so for sports.Footnote4 The assumption is straightforward: people’s stances towards specific sociopolitical sports issues depend on their party-political orientations.Footnote5 Without going into detail on Norwegian politics, I hypothesise that left-radical parties are most favourable for sports involvement in problems linked to classic leftist issues such as economic (class) inequalities but also more “new” leftist issues such as integration of immigrants, gender equality, racism and sexual identities. Right libertarian political orientations have the opposite effect (H5).

Social background: Age, gender and social class

People’s social backgrounds might affect their opinions on sports’ sociopolitical responsibilities in three ways.

First, previous research has shown that women tend to be more concerned with values and social issues than men when asked in surveys (Schwartz & Rubel, Citation2005). Feminist researchers have revealed that many women also have gender-specific experiences from their sports participation (Hartmann-Tews & Pfister, Citation2003). Hence, I expect women also to be more concerned with sports’ sociopolitical responsibilities. I expect this tendency to be especially relevant to gender issues (H6).

Second, young people are traditionally assumed to be more politically radical than older people (Peterson et al., Citation2020), which might materialise in two directions: left and right. Young people with a left political orientation may be likely to support sports’ involvement in struggles for equality; both social liberal ‘sports for all’-policies and more radical issues, such as feminism, racism, minority politics, sexuality, and the environment. Young people may also be attracted to right-wing libertarian values and be sceptical of social institutions’ political involvement in general, and this rightist stand has recently been combined with a specific anti-elitist populism (Freeden, Citation2017; Mudde & Kaltwasser, Citation2012; Rosenblatt, Citation2018). v

Third, people with a high socioeconomic status (education) are traditionally more involved in both sports and politics, and even though I do not expect the effect to be strong, I hypothesise that higher education will lead to support for asking for socio-political responsibility for sports (H8).

Two problem issues are less obviously grasped by the above theoretical framework: the inclusion of disabled people and doping.

For disabled people’s inclusion in sports, solutions are both diverse and complex—to take an integrated or separatist approach (Sørensen & Kahrs, Citation2006)—and in many cases, the issue is costly and consequential to address. The problem is, however, neither high on the political agenda nor very contested, so I would expect a medium-high concern without clear social distinctions in interest (H9).

Doping is a special issue because it is more genuinely related to sports: it is self-inflicted and destructive for sports but seldom harmful to others. This makes it reasonable to assume that people would expect sports organisations themselves – who else? – to be responsible for tackling the doping challenge (Breivik, Citation1987; Houlihan, Citation2002). This yields regardless of political orientation or social background. Our hypothesis (H10) becomes that doping should be seen as an issue where sports organisations should take responsibility, but this position is not socially distinctive. For a summary of hypotheses, see .

Table 1. Summary of hypotheses/assumptions.

Data and methods

This study is based on a stratified random sample of Norwegians aged 18–79. The survey was organised by ISSP (https://issp.org) and was distributed in the autumn of 2020 (a little late due to COVID-19 restrictions) by the NSD (https://sikt.no). The survey was sent to 4,400 people (a random sample taken from the population register), and a net sample of 1,131 responded (a 26% response rate). The survey consisted of combined postal and web surveys, and all contact with the respondents was conducted through ordinary mail.

ISSP surveys consist of an international core module and supplemental questions for each nation. Two questions specific to the Norwegian survey addressed sports-related issues. The first was related to the core aspect of our study and asked, ‘How important do you think various issues should be for the Norwegian Sport Federation (NIF) and Norwegian sports clubs?’ Note that this leaves out all sports and physical activity outside NIF: Fitness, DIY-sports and non-club sports and exercise. The issues listed were ‘improve public health’, ‘work against racism’, ‘preserve nature and the environment’, ‘contribute to the integration of people with disabilities’, ‘contribute to equality between genders’, ‘contribute to the integration of immigrants’, ‘work against doping’, ‘contribute to the local community’, ‘work for opportunities for all to afford sports’, and ‘work against discrimination based on sexual orientation’ .

Two challenges in interpreting the main question should be noted. First, the question established a noncommittal way of posing a normative stand, since there is a low threshold for saying that sports should take on social and political responsibilities. Second, the question pointed (for most respondents) to sports organisations (not “me”) as responsible for taking sociopolitical action. Together, these factors would probably make it easy to say, ‘Yes, sports should, for example, stand against racism’, and the results probably indicates a too high level of support for sports’ sociopolitical responsibilities. A more concrete prioritisation or choice between concrete options (e.g. ‘Should sports clubs spend more of their resources on immigrants?’) would probably have deterred respondents from as easily stating that sports should play a sociopolitical role. I also know from previous research that people (leaders in sports) tend to overestimate their willingness and ability to address social responsibilities compared to the actual implementation of such visions (Fahlén et al., Citation2014; Nagel et al., Citation2020; Seippel, Citation2020). The second ‘sports question’, what I call involvement in sports, asked whether people were affiliated with sports (i.e. whether they were members of or volunteers in sports clubs). I also included four more variables in the study: gender, age, education, and political party voting ().

Table 2. “How important do you think various issues should be for NIF and Norwegian sport clubs?”. Percentages. N = From 1082 to 1096.

Table 3. Independent variables.

Table 4. OLS-regression. Dependent variable; Index 0-10. How many problem-issues do each person see as “very important” (see ). Coefficients (standard errors). *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

The data analyses consisted of simple relative frequencies and ten multiple logistic regression models (one for each problem issue). I ran logistic regressions because the dependent variables were very skewed: Those seeing each issues as ‘very important’ versus the rest. The full results of these regressions are included in the Appendix. In the main text, because logistic regression analyses are hard to interpret (they move in logits and interact with independent variables), I provide four figures showing the average marginal effects (AMEs) for a selection of the independent variables. The AMEs are based on the logistic regression coefficients and show the effect on the dependent variable (expressed in probabilities, not logits) of a one-unit change in the independent variable. For example, AME = 0.2 for the independent variable ‘female’ means that a one unit ‘change’ in gender—comparing women to men—on average (across the units in the independent variable) implies that the probability of stating that it is ‘very important’ for sports to be concerned with an issue (e.g. gender equality) increases by 0.2 (or 20%).

Results

Sports should take socio-political responsibilities: the general picture

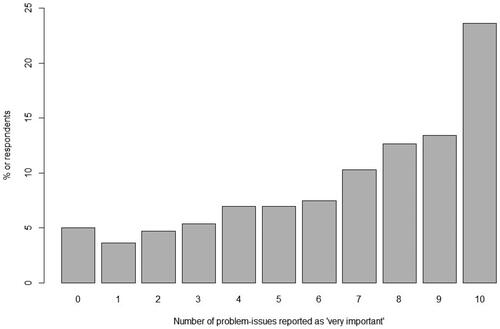

To investigate people’s general tendencies to ascribe political responsibility to sports, I counted how many problem issues each respondent reported as ‘very important’. Each person was then assigned a score from 0 (no issues reported as ‘very important’) to 10 (all issues reported as ‘very important’) (). Those with high scores on this index think it is important that sports take socio-political responsibility. 25 percent think sports should take responsibilities for all ten issues, more than 50 percent thought so for nine of ten of the issues, 74 percent claim that sports should take responsibility for five issues or more, and only 5 percent did not claim any issues as important for sports to address. All in all, hypothesis 1 – a high proportion of people would support that sports take socio-political responsibilities – is supported. These results add to previous research documenting that people think that sports have a socio-political potential with also showing that people want sports to take socio-political responsibility and fulfil this potential.

Sports should take socio-political responsibilities: Specific problem-issues

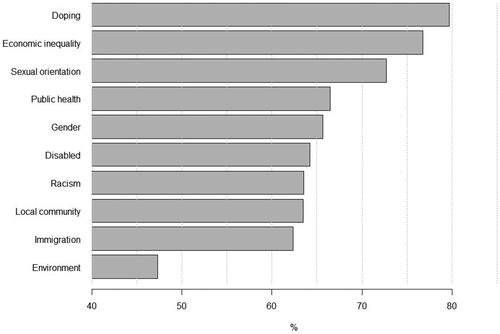

Next, I considered the extent to which people thought that sports should take responsibility for each of the ten issues. In I compare proportions of respondents stating that the each of the problem issues are ‘very important’ to sports. Even though there are significant differences between problem-issues, the overall impression is (again) that people think sports should take socio-political responsibilities.

Three issues are seen as more pressing for sports than the others: doping, economic inequality, and sexual orientation. I argued that doping is a problem-issues which it is reasonable for people to think that sports should fix itself, and people’s opinions seem to reflect this prediction (support H8). Economic inequality had the second highest ranking, which makes sense because it resonates with a general concern for social inequality as a pressing issue in Norwegian sports (P. L. Andersen & Bakken, Citation2018; Aaberge, Citation2016). It is also an issue where sports themselves could assume part of the responsibility for controlling the escalation of costs and the expectations of parental involvement (Strandbu et al., Citation2019). Sexual orientation was third on the list, perhaps because it is the issue on which sports in practice appear most out of touch with general opinions. Although sports tend to claim that all sexual orientations are welcome, very few elite athletes, especially men, stand out with non-heterosexual orientations (Magrath & Anderson, Citation2016).

Next, six issues were assigned roughly the same responsibility level, all of which mix sports-specific characteristics with general political orientations. The environment was the issue assigned the lowest importance score, probably because it is the issue with the most distant and weakest principled link to sports.

I had a vague hypothesis (2) about more personal-social issues being seen as more at home in sports politics, and political issues less so, and even though it is difficult to rank the problem-issues according to such a spectre, it seems at least justified to claim that the most contested and most distant issue – the environment – has the lowest ranking as a relevant policy-issue for sports.

Who supports sports’ sociopolitical responsibilities: the general view

I ran an OLS-regression for the problem-issue index, and found that two sets of variables had significant influence Women are more positive towards sports taking socio-political responsibility (support H6). For political parties, the Progress party (new right) and Centre party (rural) both oppose sports’ political involvement (supporting H4, H5).

Who supports sports’ sociopolitical responsibilities: Specific issues

We have seen that many respondents mean that sports should take on sociopolitical responsibilities. However, it is not reasonable to assume that all respondents should do so to the same extent, and to grasp who thought so for which issues is important for understanding and handling the sociopolitical and operational potential of sports. I ran ten logistic regression analyses to answer these questions. (Appendix) reports the full results for all ten models. Here, I graphically illustrate the most consistent and relevant results.

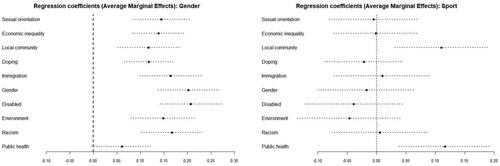

For social background, I found, as assumed, that more female than male respondents stated that sports should take on sociopolitical responsibilities (). This was true and statistically significant for all issues (support H6). The tendency was strongest for facilitating sports for people with disabilities and gender inequality (support H6), whereas it was weakest for public health. A gender related AME of 0.21 (for the disability issue) implies that, all other being equal, the models predict that female respondents are 21% more likely than men to state that the disability issue is ‘very important’ for sports to address. Age was only statistically significant for one issue – doping (supporting H7). Education had a positive effect for health issues and a negative effect for gender, economic inequality, and sexual orientation issues. The dominant negative effects of education contradicts H8.

Figure 3. Regression coefficients (AME) for (a) gender and (b) sports affiliation for each of sports political issue. Dots are values for AME regression coefficient, dotted lines indiate two standard deviations distance from regression coefficient values.

I hypothesised that affiliation with sports would matter most for issues close or intrinsic to sports: especially public health and social community building. Findings support H3 () and indicate that those affiliated to sports see sports’ political potential primarily as lying in the activities that are close to – low in cost, small in consequences – sports. Apart from the two issues on which sports insider respondents were more positive than the rest, the effects of being affiliated with sports were close to zero or negative.

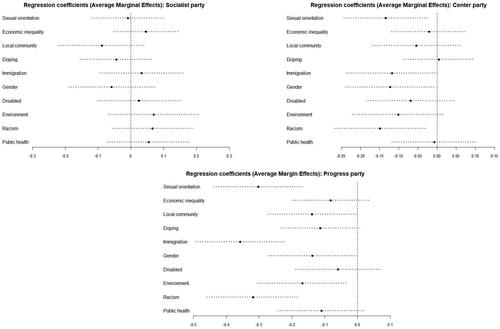

Some sports problem-issues are more politically contested than others. I included political party voting as an independent variable. Factor variables need a contrast in regression analyses, and in this case, the Labour Party was assigned this role because it represents a type of mainstream policy position. shows the most interesting finding, sorted from left to right politically.

Figure 4. Regression coefficients (AME) for (a) Socialist Party, (b) Centre Party and (c) Progress Party for each of sports political issue. Dots are values for AME regression coefficient, lines indiate two standard deviations distance from regression values.

I suggested some collective mobilising through sports to come from the left, and a libertarian scepticism to come from the right. The socialist respondents are never far from the zero line, and their supposed state-friendly collectivism does not seem to carry over to sports as a case of civil society.

The Centre Party has its roots as the former farmers’ party, it supports rural and regional interests with, in recent years, a touch of populism and anti-elitism. The respondents saw all but one issue (doping) as irrelevant for sports socio-political involvement, and two problem-issues were statistically significantly different: sexual orientation and racism should not be a concern for sports, according to Centre Party voters.

Furthest to the right among the established parties, the respondents who voted for the Progress Party were even more sceptical of sports taking a political stand than those voting for the Centre Party. Three issues were clearly not considered a concern for sports: racism, the integration of immigrants, and sexual orientation. Hence, the Progress Party seems to represent a culturally conservative and immigration-sceptical policy when it comes to sports. I see this as a support of H4 and H5.

Summary and discussion

The public discourse on sports leaves the impression that people expect something more from sports than exercise, competition and physical activity. There are so many problems related to modern sports that someone should somehow step up and take some form of social and political responsibility.

In a survey of the Norwegian population, we find high levels of support for sports taking on such social and political responsibilities. I asked about ten different problem issues: public health, racism, environment, disabilities, gender, immigration, doping, local community, economic inequality, and sexual orientation. For nine out of the ten issues, the percentages of respondents who said that these issues should be ‘very important’ for sports varied between 80% (for doping) and 62% (for the integration of immigrants). The tenth issue, which was the exception, was environmental issues, with ‘only’ 44% stating that this should be ‘very important’ for sports.

In summary, there is high support for sports taking a stand on social and political issues. I see, however, two caveats to these findings. First, it is easy to expect someone else, rather than oneself, to act when given the opportunity to do so, and second, sports have a tradition for stating their willingness to engage with such non-sports issues but tend to be more hesitant about realising social ideals when it comes to concrete action. Nevertheless, the conclusion is that there is a potential for more sociopolitically conscious sports.

I have showed how these sociopolitical issues vary in importance according to how close and intrinsic they are to sports activities (health being an example of closeness, the environment being the most distant), people’s social background (age, gender and education) and how politicised issues are (again, health versus the environment being examples). Three findings deserves special attention.

First, women are likelier to favour sports’ sociopolitical involvement for all issues than men. This yields particularly regarding people with disabilities and gender equality, less so for health and community (the most inherent issues). These tendencies are probably both due to gendered value patterns and gendered experiences from sports. Two political implication stand out. First, the results point towards women as a more potent socio-political force than men for modern sport, especially for some issues. Second, one should be aware of gender differences in support for issues, and when possible, try to build alliances to develop sports in favourable socio-political directions.

Second, people who are affiliated with sports tend to see the issues close to sports (health and community) as areas where sports should make a sociopolitical effort. This is because changes in sports have varying cost and consequences for those taking part in sports. These differences between those affiliated to sports and those not being so, is a reminder of the fact that one should be aware of costs of and consequences for those directly affected when sports policies are developed and implemented. Thinking of the two preceding findings together – gender and affiliation differences – points to the need of being aware of both experiences and interests of those affected when developing sports policies.

Third, a noteworthy pattern when investigating stances on sports’ sociopolitical responsibilities is that, for contentious issues (such as racism and the environment), those who vote for the Progress Party and the Centre Party are sceptical of sports becoming sociopolitically involved. This scepticism probably comes from a mixture of libertarian values (political non-interference) and populism/anti-elitism: Society (including sports) is best left alone to develop in a positive direction, and distant elites should not decide how sports should change. So, even though the general climate for politicising sports are positive, there are also political counter forces one should take into consideration to succeed with sports policies.

As part of the background for this study, I pointed out two general developments that are relevant for sports in modern societies—sportification and ‘systems colonialising the lifeworld’ (commercialisation/bureaucratisation). First, modern sports are sportified: they are secularised, equal, specialised, rationalised, bureaucratised, quantified, and focused on achieving records. The outcome is that sports narrowly focus on performance, holding that everything benefitting performance should be welcomed and that sports should otherwise be left alone; that is, concerns interfering with performance and records should be ignored. This development has helped sports progress at the same time as it has made sports one-dimensional. Sports are instrumentalised at the cost of ethical and aesthetic concerns.

Second, we have what Habermas see as the colonialisation of the lifeworld through commercialisation (sports as business) and politicisation (sports as a vehicle for legitimating (non-democratic) politics). Such developments imply a diagnosis of sports as being robbed of its potential to fulfil the social and political potentials inherent in a more ideological understanding of sports as part of civil society (Gammelsæter & Loland, Citation2023; Morgan, Citation1994; Walzer, Citation1992). In short: colonialisation weakens sports’ capacity to take on sociopolitical responsibilities. Together, there is a development towards one-dimensional and commercialised and bureaucratised sports crowding out playfulness, ethics, aesthetics and sociopolitical responsibilities from (elite) sports.

Considering such perspectives, the results of this study point towards a possible trend of (re)politicisation of sports. Other studies confirm that people think that sports have a socio-political potential (E. Davis & Knoester, Citation2020; Meier et al., Citation2023; Seippel, Citation2019), this study indicate that sports could and should use this potential—take stands and correct some of sports’ ethically dubious developments. For sports and sports politicians, there is an opportunity to make modern sports more sensitive to sociopolitical issues, more critical of commercial and political interests, and better able to realise sports’ inherent values. At the same time, it is important, for those who aim to realise this sociopolitical potential, again to notice (1) the variation in what types of sociopolitical issues people see as appropriate and relevant for sports actors to address and (2) how various social groups, based on gender, affiliation with sports, or political orientation, vary in the issues they see as suitable for sports’ sociopolitical involvement.

As pointed to in the introduction, modern sports operate in separate worlds. In line with the diagnosis of sportification and a solution based on civil society as a counter force, a more radical organisational measure could be, instead of struggling with stepwise policy improvements, to accept sports’ separation and keep various sports in distinct compartments. One possibility is to have commercial elite sports in one, civil society organised grassroot sports in the other. Another possibility is, in a reminiscent way, to place the most commercial sports – in the Norwegian case football and ski sports and perhaps some more – in one camp, the less commercial sports in the other. I have mentioned three areas in which sports depend on the wider society for social support—recruitment of volunteers, public funding, and commercial sponsors—and the above insight and policy suggestions has repercussions for how sports might communicate with and raise resources from these actors/areas.

Five opportunities for future research stand out. First, more detailed information could be helpful in answering the questions raised in this study: A more specific understanding of issues (e.g. the environment and disabilities have several aspects with very different implications for sports); how those issues are viewed by different sports and various group of exercisers outside the NIF-system, and how opinions vary by time could be valuable. In addition, while the focus in this study was on organised sports, it would be interesting to consider the politicisation of the fitness industry and ‘non-organised’ sports. Second, a more informed theoretical framework could be helpful, especially for identifying specific social mechanisms: How do specific interests, experiences and norms help and hinder sports concern with non-sports issues? Third, in line with an improved theoretical framework, a better analysis of how sports might move from words and loose commitments to practical action could be helpful. Fourth, qualitative methods could help underpin all the investigations mentioned above. Finally, the Norwegian case may be unique, and insights into the socio-political aspects of sports in other nations would be needed to meet global challenges.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

4 Question of social justice in sports could be discussed on two levels. First, reflecting a dominant sport for all policy (St Meld, Citation2012) a (rather) consensual social liberal ideology could make almost any one supportive of taking on inclusive sports policies (and supporting sports themselves to do so). Second, however, some of the problem-issues, especially feminism and racism, exists in more radical outlets where the challenge is not only to let all people in, but to challenge existing sport practices to change: This is sports as a question of recognition and identity politics more than sports as a good (W. Andersen & Loland, Citation2017; Fraser & Honneth, Citation2003; Honneth, Citation1995). Hegemonic masculine and whiteness-ideologies result in sports being more welcoming for some than for others (Connell, Citation2005; Hylton, Citation2010).

5 For an overview of Norwegian political parties, see Aardal and Bergh (Citation2022).

References

- Aaberge, R. (2016). Inntekstulikhet i Norge i lys av Piketty-debatten [In view of the Piketty debate: Inequlities in incomes in Norway]. Samfunnsspeilet, (1), 3–9.

- Aardal, B., & Bergh, J. (2022). The 2021 Norwegian election. West European Politics, 45(7), 1522–1534. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2022.2062136

- Acemoglu, D. (2012). The world our grandchildren will inherit: The rights revolution and beyond. National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. https://ideas.repec.org/p/nbr/nberwo/17994.html

- Alrababa’h, A. L. A.’., Marble, W., Mousa, S., & Siegel, A. A. (2021). Can exposure to celebrities reduce prejudice? The effect of Mohamed Salah on islamophobic behaviors and attitudes. American Political Science Review, 115(4), 1111–1128. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421000423

- Andersen, P. L., & Bakken, A. (2018). Social class differences in youths’ participation in organized sports: What are the mechanisms? International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 54(8), 921–937. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690218764626

- Andersen, W., & Loland, S. (2017). Jumping for recognition: Women’s ski jumping viewed as a struggle for rights. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 27(3), 359–365. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.12662

- Bakken, A. (2019). Idrettens posisjon i ungdomstida. Hvem deltar og hvem slutter i ungdomsidretten? NOVA. RAPPORT NR 2/19.

- Benford, R. D., & Snow, D. A. (2000). Framing processes and social movements: An overview and assessment. Annual Review of Sociology, 26(1), 611–639. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.611

- Bergsgard, N. A., Mangset, P., Houlihan, B., Nødland, S. I., & Rommetvedt, H. (2007). Sport policy: A comparative analysis of stability and change. Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Bergsgard, N. A., & Rommetvedt, H. (2006). Sport and politics. The case of Norway. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 41(1), 7–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690206073146

- Boykoff, J. (2022). Toward a theory of sportswashing: Mega-events, soft power, and political conflict. Sociology of Sport Journal, 39(4), 342–351. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.2022-0095

- Breivik, G. (1987). The doping dilemma. Sportswissenschaft, 17, 83–94.

- Breuer, C., Feiler, S., Llopis-Goig, R., & Elmose-Østerlund, K. (2017). Characteristics of European sports clubs. A comparison of the structure, management, voluntary work and social integration among sports clubs across ten European countries. University of Southern Denmark.

- Breuer, C., Hoekman, R., Nagel, S., & van der Werff, H. (2015). Sport clubs in Europe: A cross-national comparative perspective. Springer.

- Cashmore, E., Dixon, K., & Cleland, J. (2023). The new politics of sport. Sport in Society, 26(9), 1611–1620. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2023.2170786

- Chalip, L., Johnson, A., & Stachura, L. (Eds.). (1996). National sport policies. An international handbook. Greenwood Press.

- Chen, C. (2022). Naming the ghost of capitalism in sport management. European Sport Management Quarterly, 22(5), 663–684. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2022.2046123

- Coakley, J. (2015). Assessing the sociology of sport: On cultural sensibilities and the great sport myth. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 50(4–5), 402–406. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690214538864

- Connell, R. (2005). Masculinities (2nd ed.). Polity Press.

- Davis, E., & Knoester, C. (2020). U.S. public opinion about the personal development and social capital benefits of sport: An analysis of the Great Sport Myth. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/s8bxq

- Davis, L., Plumley, D., & Wilson, R. (2023). For the love of ‘sportswashing’; LIV Golf and Saudi Arabia’s push for legitimacy in elite sport. Managing Sport and Leisure, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2022.2162953

- Fahlén, J., Eliasson, I., & Wickman, K. (2014). Resisting self-regulation: An analysis of sport policy programme making and implementation in Sweden. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 7(3), 391–406. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2014.925954

- Fitzpatrick, D., & Hoey, P. (2022). From fanzines to foodbanks: Football fan activism in the age of anti-politics. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 57(8), 1234–1252. https://doi.org/10.1177/10126902221077188

- Fraser, N., & Honneth, A. (2003). Redistribution of recognition? A political-philosophical exchange. Verso.

- Freeden, M. (2017). After the Brexit referendum: revisiting populism as an ideology. Journal of Political Ideologies, 22(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569317.2016.1260813

- FrivillighetNorge. (2021). Frivillighetsbarometeret. Kantar.

- Fruh, K., Archer, A., & Wojtowicz, J. (2022). Sportswashing: Complicity and corruption. Sport, Ethics and Philosophy, 17(1), 101–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/17511321.2022.2107697

- Gammelsæter, H., & Loland, S. (2023). Code red for elite sports. A critique of sustainability in elite sport and a tentative refrom programme. Europeaan Sport Management Quarterly, 23(1), 104–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2022.2096661

- Grix, J. (2016). Sport politics. An introduction. Palgrave.

- Guttmann, A. (1978). From ritual to record. The nature of modern sports. Columbia University Press.

- Habermas, J. (1987). The theory of communicative action. Volume two. Beacon Press.

- Habermas, J. (1996). Between facts and norms. MIT Press.

- Harris, S., Dowling, M., & Houlihan, B. (2021). An analysis of governance failure and power dynamics in international sport: the Russian doping scandal. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 13(3), 359–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2021.1898443

- Hartmann-Tews, I., & Pfister, G. (Eds.). (2003). Sport and women. Social issues in international perspective. Routledge.

- Honneth, A. (1995). The struggle for recognition: The moral grammar of social conflictss. Polity Press.

- Houlihan, B. (2002). Dying to win: doping in sport and the development of anti-doping policy. Council of Europe Publishing.

- Houlihan, B. (2022). Challenges to globalisation and the impact on the values underpinning international sport agreements. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 14(4), 607–620. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2022.2100808

- Hylton, K. (2010). How a turn to critical race theory can contribute to our understanding of ‘race’, racism and anti-racism in sport. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 45(3), 335–354. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690210371045

- Ibsen, B., & Seippel, Ø. (2010). Voluntary sport in the Nordic countries. Sport in Society, 13(4), 593–608. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430431003616266

- IOC. (2021). Olympic games to become “climate positive” from 2030. https://olympics.com/ioc/news/olympic-games-to-become-climate-positive-from-2030

- IWG. (2018). From Helsinki to Gabarone 2013-20|8. Retrieved from: https://iwgwomenandsport.org/2018-from-helsinki-to-gaborone-progress-report/

- Jedlicka, S. R., Harris, S., & Reiche, D. (2020). State intervention in sport: a comparative analysis of regime types. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 12(4), 563–581. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2020.1832134

- Lasch, C. (2010). The degradation of sport. In M. McNamee (Ed.), The ethics of sports. A reader. Routledge.

- Magrath, R., & Anderson, E. (2016). Homophobia in men′s football. In J. Hughson, K. Moore, R. Spaaij, & J. Maguire (Eds.), Routledge handbook of football studies (pp. 314–324). Taylor & Francis.

- Meeuwsen, S., & Kreft, L. (2023). Sport and politics in the twenty-first century. Sport, Ethics and Philosophy, 17(3), 342–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/17511321.2022.2152480

- Meier, H. E., Gerke, M., Müller, S., & Mutz, M. (2023). The public legitimacy of elite athletes’ political activism: German survey evidence. International Political Science Review. https://doi.org/10.1177/01925121231186973

- Morgan, W. J. (1994). Leftiest theories of sport. A critique and reconstruction. University of Illinois Press.

- Mudde, C., & Kaltwasser, C. R. (2012). Populism: corrective and threat to democracy. In C. Mudde & C. R. Kaltwasser (Eds.), Populism in Europe and the Americas. Cambridge University Press.

- Nagel, S., Elmose-Østerlund, K., Ibsen, B., & Scheerder, J. (Eds.). (2020). Functions of sports clubs in European societies. A cross-national comparative study. Springer.

- Nepstad, S. E., & Kenney, A. M. (2018). Legitimation battles, backfire dynamics, and tactical persistence in the NFR anthem protests, 2016-2017. Mobilization: An International Quarterly, 23(4), 469–483. https://doi.org/10.17813/1086-671X-23-4-469

- Peterson, J. C., Smith, K. B., & Hibbing, J. R. (2020). Do people really become more conservative as they age? The Journal of Politics, 82(2), 600–611. https://doi.org/10.1086/706889

- Pielke, R. J. (2016). The edge. The war against cheating and corruption in the cutthroat world of elite sports. Roaring Forties Press.

- Pinker, S. (2018). Enlightenment now: the case for reason, science, humanism, and progress. Allen Lane.

- Rosenblatt, H. (2018). The lost history of liberalism: From ancient Rome to the twenty-first century. Princeton University Press.

- Sandvik, M. R., & Seippel, Ø. (2022). Framing of environmental issues in voluntary sport organizations. Environmental Politics, 32(2), 294–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2022.2075152

- Scheerder, J., Willem, A., & Claes, E. (2017). Sport policy systems and sport federations: A cross-national perspective. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Schwartz, S., & Rubel, T. (2005). Sex differences in value priorities: Cross-cultural and multimethod studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89(6), 1010–1028. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.89.6.1010

- Seippel, Ø. (2020). Norway: The ambiguity of sports clubs and nonsports social functions. In S. Nagel, K. Elmose-Østerlund, B. Ibsen, & J. Scheerder (Eds.), Functions of sports clubs in european societies. Springer.

- Seippel, Ø. (2019). Do sports matter to people? A cross-national multilevel study. Sport in Society, 22(3), 327–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2018.1490263

- Seippel, Ø., Dalen, H. B., Sandvik, M. R., & Solstad, G. M. (2018). From political sports to sports politics: on political mobilization of sports issues. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 10(4), 669–686. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2018.1501404

- Sørensen, M., & Kahrs, N. (2006). Integration of disability sport in the Norwegian sport organizations: Lessons learned. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 23(2), 184–202. https://doi.org/10.1123/apaq.23.2.184

- St Meld, N. (2012). Den norske idrettsmodellen. Kulturdepartementet.

- Strandbu, Å., Stefansen, K., Smette, I., & Sandvik, M. R. (2019). Young people’s experiences of parental involvement in youth sport. Sport, Education and Society, 24(1), 66–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2017.1323200

- Thiel, A., Villanova, A., Toms, M., Friis Thing, L., & Dolan, P. (2017). Can sport be ‘un-political’? European Journal for Sport and Society, 13(4), 253–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/16138171.2016.1253322

- Verschuuren, P., & Ohl, F. (2023). Can the credibility of global sport organizations be restored? A case study of the athletics integrity unit. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 58(7), 1193–1213. https://doi.org/10.1177/10126902231154095

- Wagner, U., & Storm, R. K. (2022). Theorizing the form and impact of sport scandals. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 57(6), 821–844. https://doi.org/10.1177/10126902211043999

- Walzer, M. (1992). The civil society argument. In C. Mouffe (Ed.), Dimensions of radical democracy. Verso.

- Woods, J. (2022). Red sport, blue sport: political ideology and the popularity of sports in the United States. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 14(3), 489–505. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2022.2074516

Appendix

Table A1. Logistic regression. Dependent variable: “How important do you think that various issues should be for NIF and Norwegian sports clubs?” Respondents say this is “very important” versus those with other answers. Coefficients and standard errors. *p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.