Abstract

The nutritional assessment is deemed the 5th vital sign in performing a clinical evaluation in veterinary patients, as described by World Small Animal Veterinary Association since 2011. A recent report of the veterinary profession demonstrated there is an underuse of this tool which may be restricted to critically ill patients. Ageing changes in cats and dogs will cause reduction in lean body mass termed sarcopaenia, which increases mortality and morbidity and reduces QoL. Early detection of sarcopaenia can lead to appropriate advice relating to diet and exercise, which could delay and slow the onset of this damaging syndrome. The RVN can play a pivotal role in performing regular nutritional assessments in ageing patients.

Introduction

It is professionally accepted that appropriate and adequate nutrition is one of the most important factors in maintaining health and managing disease in veterinary patients (Lumbis, Citation2014). To ascertain what is appropriate and adequate, first a nutritional assessment must be completed, which should form part of the clinical examination. The veterinary nurse is perfectly positioned to play an essential role in performing a comprehensive nutritional assessment and implementing appropriate dietary plans in line with any veterinary surgeon’s (VS) diagnoses. Since 2011, the World Small Animal Veterinary Association (WSAVA), Nutritional Assessment Guidelines have been available for use by veterinary nurses to enable this to be carried out systematically (Freeman et al., Citation2011). These guidelines name the nutritional assessment as the 5th vital sign, after temperature, pulse, respiration and pain assessment. However, in a recent study of 2740 veterinary health workers (of which 85% were VS or qualified nurses/technicians), only 27% were aware of the WSAVA Guidelines, with only 30% stating they always perform a nutritional assessment when evaluating a patient’s health (Lumbis & de Scally, Citation2020). Factors cited in the report as affecting the performance of the nutritional assessment included lack of practice policy, personnel, opportunity and inconsistencies in colleagues. Given the accepted clinical importance of nutritional assessments, it is our duty as veterinary nurses to ensure we enhance our own clinical practice and positively influence the practice of those around us. Blending nutritional assessments into everyday protocols requires the whole practice team to work together with VS, nurses and reception staff providing clear and appropriate recommendations (Rollins & Murphy, Citation2019) This will ensure patients receive timely and appropriate nutritional support throughout their lives.

The importance of nutritional assessment

Full definitions of the terms sarcopaenia and cachexia are detailed below, as reported by Saker (Citation2021). See for a comparison of metabolic consequences.

Sarcopaenia

“Commonly defined as the progressive and generalised loss of skeletal lean muscle mass and function with aging in the absence of disease. A focus now includes the functionality of muscle as well as the mass; thus, a clinical definition would include decreased gait speed or grip strength in a person with low muscle mass”.

Cachexia

“Defined as a complex metabolic syndrome associated with underlying illness and characterised by loss of muscle mass with or without loss of fat mass. The prominent clinical feature of cachexia is weight loss in adults. It is associated with a decreased QoL and poor prognosis”.

Table 1. Comparison of the metabolic consequences of sarcopaenia to cachexia (Evans, Citation2010).

Following an iterative process, the nutritional assessment must include an evaluation of the following factors: clinical examination of the patient, dietary history and patient environment (Eirmann, Citation2016). It is advised by the American Animal Hospital Association (AAHA) and WSAVA that the nutritional assessment should be performed every time a patient presents to the veterinary practice for consultation, as each factor can change throughout the pet’s lifetime. Regular evaluation will pick up changes as soon as possible to allow for appropriate advice and adjustment to be implemented (Baldwin et al., Citation2010; Freeman et al., Citation2011).

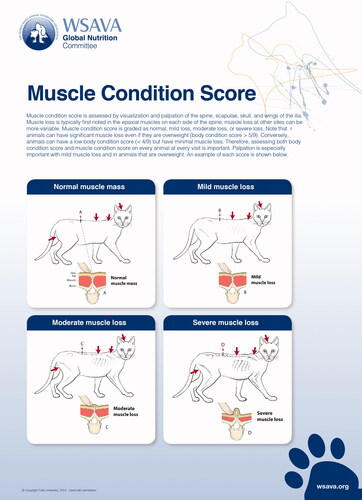

Whilst most healthy pets may only require a quick evaluation of appropriate factors, if nutritional risk factors are present, such as ageing, poor body condition score (BCS), poor muscle condition score (MCS, see ), period of anorexia, unexplained weight loss or presence of systemic disease processes, a more comprehensive investigation will be required. Loss of lean body mass (LBM) in veterinary patients, namely in the form of sarcopaenia and cachexia, is associated with an increase in morbidity and mortality, (Freeman, Citation2012; Santiago et al., Citation2020). Sarcopaenia is the loss of LBM which occurs with ageing and can occur in the absence of disease. Cachexia is the loss of LBM associated with disease processes such as congestive heart failure (CHF), chronic kidney disease and cancer. Both syndromes may occur at the same time, for example in an elderly patient with CHF. The increased life span of today’s cat and dog population in turn, increases the incidence of sarcopaenia and cachexia (Freeman, Citation2018). The effects of these syndromes can include weakness, anorexia, reduced immune function and poor quality of life (QoL). These are all factors which can contribute to morbidity, mortality and an owner’s decision to euthanise their pet (Mallery et al., Citation1999). Early detection of these syndromes will guide appropriate dietary adjustments of key nutrients which can help to slow the progression of LBM losses and support a prolonged and better QoL (Saker, Citation2021).

The nutritional assessment should comprise an evaluation of the following factors at every visit (Groves, Citation2019):

Patient-specific considerations such as species, age and lifestyle

BCS and MCS assessment– visually and by palpation

Current health status and presence of disease

Comprehensive dietary history, including appetite, meals and snacks

Current feeding method e.g., measured or ad.lib.

Client-specific requirements e.g., financial, availability, personal nutritional philosophy and any other constraints

This can be done via use of a pre-set questionnaire and should involve verbal discussion with the owner also. For full details of the Nutritional Assessment, including Body and Muscle Condition Scoring, nutritional history forms and checklists see

Figure 1. Provided courtesy of the World Small Animal Veterinary Association (WSAVA). Available at the WSAVA Global Nutrition Committee Nutritional Toolkit website: http://www.wsava.org/nutrition-toolkit. Accessed July 2nd 2021. Copyright Tufts University, 2014.

https://wsava.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/WSAVA-Global-Nutrition-Toolkit-English.pdf

Consideration is also needed for when a pet becomes aged. Cats are considered senior from 7–11 years and geriatric from 12+ years, with dogs age status being heavily dependent on breed size; small dogs are considered senior from 10+ years, with large dogs senior at 5–8 years (Groves, Citation2019).

In sarcopaenia loss of LBM is often accompanied by an increase in fat mass in ageing dogs and senior cats, meaning that the BCS can remain unchanged, masking the presence of sarcopaenia in the absence of a full nutritional assessment, which would include MCS (Freeman, Citation2018). One longitudinal study of cats showed healthy cats lose approximately one-third of their LBM between the ages of 10–15 years (Perez-Camargo, Citation2003); similar results were also seen in an additional longitudinal report (Cupp & Kerr, Citation2010). In dogs, similar findings have been presented, with loss of LBM occurring with age and longevity linked to slowest loss of LBM (Adams et al., Citation2015).

The lack of functionality, described here in a human context of grip strength, can be partly assessed in dogs and cats using a detailed discussion with the owner. Targeted questioning can identify whether the patient has become less active or less able to perform movements, such as climbing or jumping into a car boot, for example. Exercise is the most effective therapy for managing sarcopaenia, therefore it is vital to have discussions with owners about maintaining activity levels throughout the pet’s life. Owners can also be taught some physiotherapy techniques to use at home, such as use of steps, stairs and ramps, pole walking, weight shifting and use of treats to encourage head and neck movements. This also helps to maintain the bond between owner and pet. Veterinary hydrotherapy pools are a safe way for pets to swim to maintain muscle mass, especially when ageing, however, they do involve financial costs.

Since sarcopaenia is reported to be common in ageing dogs and cats, veterinary nurses should be confident in assessing its presence and advising appropriate exercise and dietary changes to help delay progression and reduce the morbidity and mortality factors associated with this syndrome.

The pathophysiology of cachexia can be described to include four aspects: increased energy requirements, decreased nutrient absorption, decreased energy intake and alterations in metabolism; these are generally accompanied by a chronic state of inflammation (Saker, Citation2021). Catabolic depletion of protein reserves is one of the most marked features of critically ill patients, which can also be seen in chronically ill patients suffering with systemic disease (Latimer-Jones, Citation2020). In a healthy animal, simple starvation causes metabolic adaptations which result in the utilisation of fat as the primary source of energy. However, in a patient with chronic or acute illness, amino acids become the primary energy source, causing catabolism of LBM and muscle wasting, leading to cachexia, loss of strength, immune function and reduced survival (Peterson, Citation2018). Obviously, treatment in these cases will focus on the presenting disease process in discussion with the veterinary surgeon, but physiotherapy and appropriate diet can also delay and reduce the progression of LBM losses.

Dietary support

Diet for the multitude of specific diseases is beyond the scope of this article. Therefore, the focus will be on dietary consideration to reduce loss of LBM in healthy ageing patients to minimise sarcopaenia. Maintaining optimal BCS and MCS should be prioritised in senior pets (Churchill & Eirmann, Citation2021). This will reduce the harmful effects of obesity and sarcopaenia, delay the onset of osteoarthritis and frailty, thus increasing length and QoL.

Protein

Dietary requirements must consider the senior animal’s species, age, activity levels and fat stores. Cats between the ages of 6–10 years are more likely to be obese and have lower energy requirements, whilst cats over 12 years tend to lose weight and LBM and have a greater energy requirement compared to middle aged individuals (Gajanayake, Citation2017). Senior cats may have decreased protein and fat synthesis, with senior dogs also having decreased protein synthesis, but generally, dogs maintain fat digestion. Aged cats and dogs should not receive dietary protein restriction, unless this is indicated by a diagnosed protein sensitive condition (Churchill & Eirmann, Citation2021). Whey protein containing leucine has shown to reduce proteolysis and enhance protein synthesis and dietary lysine can also help reduce LBM losses in ageing (Laflamme, Citation2018). In adult dogs, protein should be supplied at approximately 2.55 g protein per kg body weight, in cats 5 g protein per kg body weight, in senior pets, this requirement can increase by approximately 50% (Churchill & Eirmann, Citation2021). To maintain optimal body condition, older dogs generally require fewer calories, whereas cats do not generally require a reduction in calories to maintain optimal body weight. The protein to total calorie ratio may need to be altered in ageing dogs to meet their nutritional requirements and reduce hyperadiposity. Given the reduced protein synthesis in ageing pets, protein sources should be selected for high bioavailability.

Omega-3 fatty acids

The anti-inflammatory effects of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) may have action in reducing inflammatory mediators involved with sarcopaenia and have been shown to improve muscle function (Groves, Citation2019). Adding fish oil to food is neither expensive nor associated with high risk of side effects and so can be recommended if possible. Many good quality commercial diets include EPA and DHA, so ensure appropriate discussions around current diets when making recommendations.

Other nutrients

Low serum vitamin D has been linked to increased sarcopaenia in ageing people and a reduced rate of protein synthesis in rats (Laflamme, Citation2018). Therefore, it would be prudent to ensure adequate daily intake via an appropriate diet. Further research into the preservation of LBM with vitamin D supplementation in dogs and cats is required. Antioxidants such as vitamins C and E and trace elements such as magnesium, phosphorus, selenium and vitamin B12 are currently being explored in the role of human sarcopaenia, as is the correction of acid/base imbalances (Laflamme, Citation2018).

Conclusion

The nutritional assessment is an important, but underused tool in the appropriate dietary management of ageing pets. Sarcopaenia is common in ageing pets and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality factors and reduced QoL leading to decisions to euthanise. Veterinary nurses should ensure they remain vigilant in performing a nutritional assessment every time the pet visits for a consultation or in-patient stay to identify risk factors and LBM losses. Any recommended dietary and exercise changes can be discussed and agreed with the owner and implemented to delay the onset and progression of sarcopaenia. Protein is an important factor and should only be reduced in the presence of diagnosed protein sensitive conditions. Senior and geriatric patients generally required higher levels of dietary protein than adults. Other nutrients to consider include EPA and DHA and vitamin D. The whole practice team should work together to establish achievable protocols to ensure that nutritional assessments become the daily normal and not just when patients present in a critically diseased state. Consensus should be reached on aspects such as BCS and MCS to enable clarity between professionals when recording on clinical records and enable tracking of trends.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflicts of interest are reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Susan L. Holt

Susan L. Holt MRes B.Sc. (Hons) RVN Cert PM&A PGCHE FHEA Susan qualified in 1994, spending time in a range of roles including first opinion, charity and referral work, until moving into the education sector in 2016. Currently, Susan is working as a Lecturer and Programme Tutor for the Veterinary Nursing Department within the University of Bristol’s Vet School. She maintains some clinical work through volunteering for StreetVet, an RCVS registered practice delivering free veterinary care and advice for the homeless clients and their pets.

Email: [email protected]

References

- Adams, V. J., Watson, P., Carmichael, S., Gerry, S., Penell, J., & Morgan, D. M. (2015). Exceptional longevity and potential determinants of successful ageing in a cohort of 39 Labrador retrievers: Results of a prospective longitudinal study. Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica, 58(1), 29. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s13028-016-0206-7

- Baldwin, K., Bartges, J., Buffington, T., Freeman, L. M., Grabow, M., Legred, J., & Ostwald, D. (2010). AAHA nutritional assessment guidelines for dogs and cats. Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association, 46(4), 285–296. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5326/0460285

- Churchill, J. A., & Eirmann, L. (2021). Senior pet nutrition and management. Veterinary Clinics of North America - Small Animal Practice, 51(3), 635–651. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cvsm.2021.01.004

- Cupp, C. J., Kerr, W. W. (2010). Effect of diet and body composition on life span in aging cats. Proc Nestlé Purina Companion Animal Nutrition Summit: Focus on Gerontology.

- Eirmann, L. (2016). Nutritional assessment. Veterinary Clinics of North America - Small Animal Practice 46(5), 855–867. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cvsm.2016.04.012

- Evans, W. J. (2010). Skeletal muscle loss: Cachexia, sarcopenia, and inactivity. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 91(4), 1123S–1127S. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2010.28608A

- Freeman, L. M. (2012). Cachexia and sarcopenia: Emerging syndromes of importance in dogs and cats. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 26(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-1676.2011.00838.x

- Freeman, L. M. (2018). Cachexia and sarcopenia in companion animals: An under-utilized natural animal model of human disease. JCSM Rapid Communications, 1(2), 1–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2617-1619.2018.tb00006.x

- Freeman, L., Becvarova, I., Cave, N., MacKay, C., Nguyen, P., Rama, B., Takashima, G., Tiffin, R., Tsjimoto, H., & van Beukelen, P. (2011). WSAVA nutritional assessment guidelines. The Journal of Small Animal Practice, 52(7), 385–396. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-5827.2011.01079.x

- Gajanayake, I. (2017). Senior pets–dietary advice to offer cat and dog owners. vettimes.co.uk. Retrieved June 6, 2021, from https://www.vettimes.co.uk/app/uploads/wp-post-to-pdf-enhanced-cache/1/senior-pets-dietary-advice-to-offer-cat-and-dog-owners.pdf.

- Groves, E. (2019). Nutrition in senior cats and dogs: How does the diet need to change, when and why? Companion Animal, 24(2), 91–101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.12968/coan.2019.24.2.91

- Laflamme, D. (2018). ‘Effect of diet on loss and preservation of lean body mass in aging dogs and cats. purinainstitute.com. Retrieved June 6, 2021, from https://www.purinainstitute.com/sites/g/files/auxxlc381/files/2018-05/CAN2018-final_allproceedings.pdf#page=45.

- Latimer-Jones, K. (2020). The role of nutrition in critical care. The Veterinary Nurse, 11(4), 166–171. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.12968/vetn.2020.11.4.166

- Lumbis, R. H. (2014). Reflections on nutritional assessment: The Veterinary Nurse workshop 2014. The Veterinary Nurse, 5(2), 64–67. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.12968/vetn.2014.5.2.64

- Lumbis, R. H., & de Scally, M. (2020). Knowledge, attitudes and application of nutrition assessments by the veterinary health care team in small animal practice. The Journal of Small Animal Practice, 61(8), 494–503. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jsap.13182

- Mallery, K. F., Freeman, L. M., Harpster, N. K., & Rush, J. E. (1999). Factors contributing to the decision for euthanasia of dogs with congestive heart failure. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 214(8), 1201–1204. Retrieved June 2, 2021, from http://europepmc.org/article/med/10212683

- Perez-Camargo, G. (2003). Cat Nutrition: What Is New in the Old?, researchgate.net. Retrieved June 6, 2021, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/289214205.

- Peterson, M. (2018). Cachexia, sarcopenia and other forms of muscle wasting: Common problems of senior and geriatric cats and of cats with endocrine disease, purinainstitute.com. Retrieved June 6, 2021, from https://www.purinainstitute.com/sites/g/files/auxxlc381/files/2018-05/Peterson-Cachexia%2CSarcopenia and Other Forms of Muscle Wasting.pdf.

- Rollins, A. W., & Murphy, M. (2019). Nutritional assessment in the cat: Practical recommendations for better medical care. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery, 21(5), 442–448. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1098612X19843213

- Saker, K. E. (2021). Nutritional concerns for cancer, cachexia, frailty, and sarcopenia in canine and feline pets. Veterinary Clinics of North America - Small Animal Practice, 51(3), 729–744. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cvsm.2021.01.012

- Santiago, S. L., Freeman, L. M., & Rush, J. E. (2020). Cardiac cachexia in cats with congestive heart failure: Prevalence and clinical, laboratory, and survival findings. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 34(1), 35–44. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jvim.15672