ABSTRACT

Background: For interferon beta-1a subcutaneously three times weekly (IFN β-1a SC tiw), administration options include manually injected prefilled syringes; a preassembled, single-use autoinjector; and a reusable autoinjector. This study evaluated patient-perceived ease of use of two injection devices.

Research design and methods: REDEFINE, a Phase IV, multicenter crossover study, randomized patients with multiple sclerosis and ≥5 weeks’ IFN β-1a 44 μg SC tiw use to 4 weeks using a single-use autoinjector, then 4 weeks using a reusable autoinjector, or vice versa. The primary endpoint was the proportion rating each ‘easy’ or ‘very easy’, with/without regard to previous device experience.

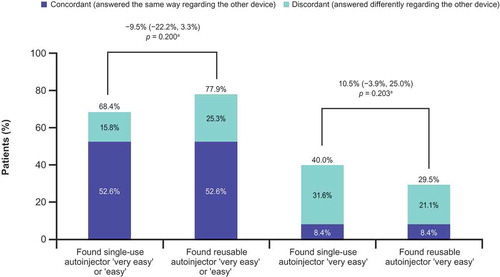

Results: Of 97 randomized patients, 29 had most recent experience with manual injection; 23 with single-use autoinjector; and 45 with reusable autoinjector. 68.4% found using the single-use autoinjector very easy or easy, versus 77.9% for the reusable device (difference −9.5%; p = 0.200). 40.0% versus 29.5% found the respective devices very easy (difference 10.5%; p = 0.203).

Conclusions: Most patients found both autoinjectors easy or very easy to use. Having two viable options may help accommodate patient preferences. Ease of administration and patient satisfaction relates to adherence; satisfied patients may more likely be adherent.

Trial registration: The trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (CT.gov identifier: NCT02019550).

1. Introduction

All self-injectable disease-modifying drugs (DMDs) approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis (MS) provide patients with the option to self-inject using either a syringe or an autoinjector. Various autoinjectors are available, but information regarding the usability and patient satisfaction with different devices is limited.

For interferon beta-1a subcutaneously three times weekly (IFN β-1a SC tiw), options in the US include manual injections using a prefilled syringe (PFS), a preassembled, single-use autoinjector (Rebif® Rebidose®, EMD Serono, Inc., MA, USA), and a reusable autoinjector with an adjustable injection depth feature (Rebiject II®, EMD Serono, Inc., MA, USA). Features of the two autoinjectors are summarized in . Patient ease of use with these autoinjectors has been measured in previous single-arm trials [Citation1,Citation2].

Table 1. Comparison of single-use and reusable autoinjectors.

Adherence to treatment is associated with ease of administration and satisfaction with therapy [Citation3]. Understanding patients’ perspectives regarding the ease of use of each device, as well as overall patient satisfaction with each device, may help health-care providers identify the most suitable device for the injection of IFN β-1a SC tiw for their patients with relapsing forms of MS and increase adherence to treatment.

The REDEFINE (REbif® Rebidose® vs Rebiject® II autoinjector trial DEFINing patient reported Ease-of-use) study was a crossover study to compare the relative ease of use of these two autoinjector devices and to investigate how each is differently perceived depending on the patient’s previous experience of injection device use.

2. Patients and methods

2.1. Patients and assessments

This Phase IV, prospective, randomized, multicenter, two-arm, crossover study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT02019550) enrolled patients with relapsing–remitting MS (RRMS), aged 18–65 years, from 32 sites in the US. The trial was conducted in accordance with the protocol, the International Conference on Harmonisation guideline for Good Clinical Practice, and applicable local regulations, as well as ethical principles that have their origin in the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol EMR200136-573 was approved by Copernicus Independent Review Board, Durham, NC (tracking number QUI1-13-464); some sites also received approval from local/institutional review boards. All patients provided signed informed consent and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act authorization before any trial-related activities were performed. Eligible patients were receiving IFN β-1a 44 µg SC tiw by manual PFS injection, the single-use autoinjector, or the reusable autoinjector for at least 5 weeks before the screening assessment (up to 14 days before Study Day 1).

When enrollment began, only patients without previous use of the autoinjectors were eligible. Shortly after the trial began, patient enrollment fell behind expected targets; therefore, a single protocol amendment, protocol amendment 1, was issued on 27 October 2014 primarily to increase enrollment. Results of a site survey indicated that the majority of patients receiving IFN β-1a 44 µg SC tiw were already using an autoinjector, and the patients still receiving manual PFS injection were unlikely to want to try an autoinjector. Therefore, the Sponsor decided to modify the inclusion criteria to allow for the enrollment of patients with previous experience (at least 5 weeks) using an autoinjector. The enrollment period was coordinately extended from 8 to 18 months.

Patients were randomized (1:1) via an interactive response technology system to receive IFN β-1a 44 µg SC tiw over the 8-week treatment period in a two-period crossover design. The randomization list was created by the contract research organization according to their standard operating procedures. The investigator or delegate accessed the interactive response technology system and entered responses to the questions, and the treatment sequence was assigned by the system. Patients self-injected 12 injections using the single-use autoinjector during the first 4 weeks and then crossed over to self-inject 12 injections using the reusable autoinjector during the second 4 weeks, or vice versa (Supplementary Figure 1). Patients received training on each autoinjector at the start of each of the 4-week treatment periods. Trial personnel were to instruct patients to administer IFN β-1a 44 µg SC tiw at the same time of day (preferably the late afternoon or evening) on the same 3 days (e.g. Monday, Wednesday, and Friday) each week, at least 48 hours apart. Patients were to be reminded on the proper self-injection procedures to minimize injection-site reactions and to rotate injection sites on the thighs, lower back, arms, and abdomen to mitigate the occurrence of localized skin reactions.

Figure 1. Response to Question 14 of the User Trial Questionnaire, ‘Overall experience with using injection device’ (primary endpoint).

CI, confidence interval. aDifference (95% CI) between devices (in percentage points; single-use autoinjector minus reusable autoinjector) in the proportions of patients rating each autoinjector as ‘very easy’ or ‘easy’ to use. p value is based on the exact sign test of equality of paired proportions. Includes patients with complete data for both autoinjectors (N = 95).

At baseline, patients completed the Baseline Characteristics Questionnaire that assessed self-reported levels of disability, functional impairments, anxiety with self-injection, and fear of needles. Cognitive function was assessed at baseline using the Symbol Digit Modality Test (SDMT) via both the oral and written scores. Patients’ perceptions regarding ease of use, satisfaction, and convenience with each of the two autoinjectors were assessed at the end of each 4-week treatment period (end of weeks 4 and 8) using a User Trial Questionnaire (UTQ). Patient quality of life was evaluated at baseline and at end of weeks 4 and 8 using the Multiple Sclerosis International Quality of Life (MusiQoL) questionnaire (©MusiQoL 2008 [Citation4]). The Baseline Characteristics Questionnaire and UTQ were developed specifically for this study and have not been validated psychometrically.

The primary end point was the proportion of patients rating each autoinjector as ‘easy’ or ‘very easy,’ with or without regard to previous device experience, following the 4 weeks using each device. This end point was determined by patients’ responses to UTQ Question 14, which asks, ‘Overall, how do you rate your experience with using the injection device?’. The incorporation of previous device experience was added when the protocol was amended to include patients with previous use of the autoinjector. Secondary end points included responses to the other questions on the UTQ, which assessed topics such as patients’ level of satisfaction with using the device while traveling, amount of time needed to complete the injection, level of convenience of using the device, amount of needle anxiety while using the device, and overall satisfaction with the autoinjector. Another secondary end point was change in quality of life as assessed using MusiQoL. Safety assessments were limited to the recording of serious adverse events, as reported by the subject or observed by the investigator. Treatment compliance was based on the Drug Accountability Forms completed by the Investigator (or other designated staff member) at each site, and the information was to be entered into the electronic case report form. Subjects were instructed to bring both open and unopened packages with them to each visit in order to allow for the assessment of treatment compliance.

2.2. Statistical methods

The sample size calculation addressed the specific primary hypothesis that patients in a crossover comparison would rate the single-use autoinjector easier to use than the reusable autoinjector. The null hypothesis was that the proportion of patients who rated the single-use autoinjector as very easy or easy to use would be equal to the proportion of patients who rated the reusable autoinjector as very easy or easy to use. The alternative hypothesis was that these two proportions would not be equal. The sample size calculation was based on the exact sign test of equality of paired proportions (α = 0.05; two-tailed test). A 15% difference was deemed clinically significant and assumed under the alternative hypothesis (20% discordant pairs assumed). In order to test the hypothesis of interest with 85% power, a minimum of 80 evaluable patients would be required. Allowing for a 10% dropout rate, the required sample size was 90 patients (45 in each sequence). Analyses were performed on the intent-to-treat population, defined as the set of all enrolled patients who had received >1 dose of study drug and had >1 post-baseline evaluation/assessment. The exact sign test was used to compare differences of equality of paired proportions, with results reported as 95% confidence intervals with p-values.

3. Results

3.1. Patient disposition and characteristics

The first patient enrolled in the study on 3 March 2014, and the last patient visit occurred on 15 January 2016. The mean age of patients at baseline was 49.4 and 47.5 years in the treatment groups using the single-use and reusable autoinjector first, respectively. The majority of patients enrolled in each group were female: 87.0% in the single-use autoinjector first group and 62.7% in the reusable autoinjector first group. Of 97 randomized patients, 29 (29.9%) had most recent previous experience with manual injection with PFS, 23 (23.7%) with the single-use autoinjector, and 45 (46.4%) with the reusable autoinjector (). Ninety-three of the 97 patients completed the study according to the protocol; the CONSORT flow diagram is shown in Supplementary Figure 2.

Table 2. Patient characteristics and responses to questionnaire at baseline.

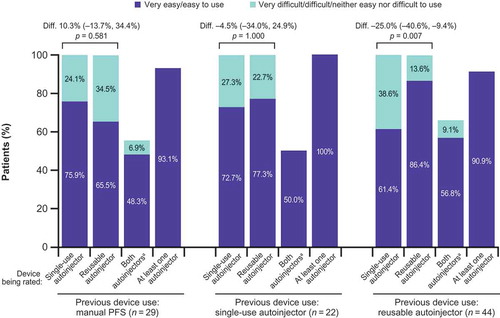

Figure 2. Autoinjector ease of use by previous injection device experience.

Diff., difference between devices (in percentage points; single-use autoinjector minus reusable autoinjector) in the proportions of patients rating each autoinjector as ‘very easy’ or ‘easy’ to use; the numbers in parentheses show the 95% confidence interval; PFS: prefilled syringe. p values are based on the exact sign test of equality of paired proportions. aPatients with concordant responses.

Median (range) oral and written SDMT scores at baseline were 51.5 (3–95) and 46.0 (1–72), respectively (). Levels of self-reported severe disability, extreme anxiety about self-injecting, and extreme needle phobia at baseline were low ().

The order that patients used each device was not deemed significant; therefore, patient responses are presented by device used (rather than sequence) in subsequent results.

3.2. Primary end point: ease of use

No significant differences were found between the two autoinjectors in the proportions of patients who rated the autoinjector as very easy or easy to use. Overall, 68.4% found the single-use autoinjector very easy or easy to use compared with 77.9% for the reusable device (difference −9.5%; p = 0.200; ). A majority of patients rated both autoinjectors as very easy or easy to use; 93.7% of patients rated at least one of the autoinjectors as very easy or easy to use.

When examining the most favorable response category alone (i.e. very easy to use) rather than the combined category of very easy or easy to use, a numerically greater proportion of patients favored the single-use autoinjector than the reusable device, but the difference was not statistically significant: 40.0% versus 29.5%, respectively, found the single-use autoinjector and the reusable device very easy to use (difference 10.5%; p = 0.203; ). Of the 38 patients who found the single-use autoinjector very easy to use, 30 (78.9%) answered differently regarding the reusable device; of the 28 patients who found the reusable autoinjector very easy to use, 20 (71.4%) answered differently regarding the single-use device.

Among those with most recent use of the reusable device, a greater proportion characterized that device (vs. the single-use device) as very easy or easy after use during the study (86.4% vs. 61.4%; p = 0.007; ). Among those with previous use of the other injection methods, no significant differences were seen in the proportion identifying either device as very easy or easy to use (). Both devices were more frequently rated very easy or easy to use by those with previous experience of using the device versus those without experience; for the single-use autoinjector, rates were 72.7% and 61.4%, respectively, and for the reusable device, rates were 86.4% versus 77.3%.

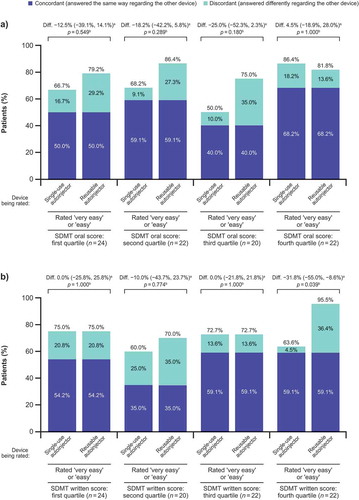

shows percentages of patients rating each device as very easy or easy to use by quartiles of SDMT oral and written scores. Previous device use for patients in the fourth quartile of the SDMT written score (i.e. patients with least cognitive disability) was mixed: 12/22 (54.5%) were previously using the reusable autoinjector, 4/22 (18.2%) were previously using the single-use device, and 6/22 (27.3%) were previously using manual injection with PFS. Among patients in the fourth quartile of baseline SDMT written score (mean SDMT written score in this quartile was 63.0 [standard deviation (SD) 4.51; range 57–72]), significantly more patients rated the reusable autoinjector as very easy or easy to use (21/22 [95.5%]) than the single-use autoinjector (14/22 [63.6%]; p = 0.039). In the other quartiles, no significant differences were seen between devices in the proportion of patients rating each as very easy or easy to use.

Figure 3. Percentages of patients rating each device as very easy or easy to use by quartiles of SDMT (a) oral and (b) written scores.

SDMT oral and written scores range from 0 to 110, with lower scores indicating cognitive deficit. Quartile 4 includes the highest values, with the least cognitive deficit. SDMT, Symbol Digit Modalities Test. aDifference between devices (in percentage points; single-use autoinjector minus reusable autoinjector) in the proportions of patients rating each autoinjector as ‘very easy’ or ‘easy’ to use. bBased on exact sign test of equality of paired proportions.

Other protocol-specified subgroup analyses (by age, gender, education level, visual deficit, upper extremity deficit, anxiety with self-injection, fear of needles, MusiQoL, etc.) found no significant differences between the devices in the proportion of patients rating each as very easy or easy to use (data not shown).

3.3. Secondary end points: other UTQ end points

Descriptions of the significant differences between autoinjectors are shown in (overall satisfaction with injection device, satisfaction with number of steps it took to complete injection, and finding it convenient to store the device).

Table 3. Responses to other questions of the User Trial Questionnaire.

When examining the most favorable response category alone (i.e. strongly agree) rather than the combined category of strongly agree/agree, several secondary end points numerically favored the single-use autoinjector over the reusable autoinjector; however, these end points were not tested for statistical significance. For the single-use autoinjector versus the reusable device, 38.5% versus 34.4% strongly agreed that they were satisfied overall with the device, 46.9% versus 37.5% strongly agreed that they were satisfied with the amount of time to complete an injection, 49.0% versus 31.3% strongly agreed that they were satisfied with the number of steps needed to complete an injection, 53.1% versus 30.2% found the respective devices extremely convenient, 33.3% versus 24.0% strongly agreed that the device features helped to minimize safety hazards, 45.8% versus 42.7% were very likely to recommend the device to others needing the medication, and 29.2% versus 26.0% strongly agreed that the device allowed for easy access to injection sites ().

3.4. Quality of life

No significant differences between devices were seen in changes from baseline in MusiQoL dimension or global index scores.

3.5. Safety

One patient experienced a serious adverse event, which was a case of staphylococcal osteomyelitis, deemed unrelated to study drug or device.

3.6. Compliance

During the first four-week period, 43 (93.5%) patients using the single-use autoinjector and 49 (96.1%) patients using the reusable device missed no injections. During the second four-week period, 49 (100.0%) and 43 (93.5%) patients using the respective devices missed no injections.

4. Discussion

In this randomized crossover evaluation of two autoinjector devices for administration of IFN β-1a 44 µg SC tiw, each autoinjector was rated as very easy or easy to use by more than two-thirds of the patients. Significant differences between the devices were found in responses regarding overall patient satisfaction, patient satisfaction with number of steps it took to complete injection, and convenience to store the device. Patients who had previous experience of using a particular autoinjector tended to rate that autoinjector more favorably than those who did not have previous experience with that device. Most patients who felt one device was very easy to use did not feel the same way regarding the other device, suggesting that choice of device can represent an important difference for some patients.

A strength of this study was its prospective, randomized design. Most previous studies of autoinjectors for administration of DMDs in MS have been non-randomized, non-controlled, single-arm studies [Citation1,Citation2,Citation5–Citation14] or cross-sectional patient surveys [Citation15,Citation16]. Several previous studies have compared autoinjector use with manual injection [Citation17–Citation19] or compared different autoinjectors to administer the same DMD product [Citation20–Citation22]. In an open-label Phase IIIb study, patients received 30 μg of IFN β-1a treatment over 4 weeks; 94% of 70 patients who completed the study preferred the prefilled pen, a single-use autoinjector, over the PFS for intramuscular delivery of IFN β-1a and found the autoinjector easy to use [Citation18]. In a crossover sub-study of 39 patients from the Phase IIIb ATTAIN trial (a dose-frequency extension of the Phase III ADVANCE study), patients perceived the peginterferon β-1a single-use autoinjector to be easy to use and convenient; overall patient satisfaction with the autoinjector was high [Citation19]. A randomized, Phase IV, open-label crossover study of 294 patients with RRMS taking IFN β-1b demonstrated that patients experienced fewer injection-site reactions with an autoinjector device (Betaject® or Betaject® Lite, Bayer Pharma AG, Berlin, Germany) over manual injection, and a survey showed that patient overall satisfaction was higher with the Betaject® Lite device over the Betaject® [Citation20,Citation22]. Although these studies cannot be directly compared with the present study due to differences in treatment, trial designs, and patient populations, a common theme is that autoinjectors lead to improvements in ease of use and patient satisfaction.

Studies such as this one comparing two different autoinjectors to self-administer the same DMD allow for injection device preferences to be investigated without confounding factors, including different dosing regimens and tolerability profiles, possibly arising when comparing injection devices using different DMDs.

Patients enrolled in this study had low levels of needle phobia. Given that several oral DMDs had already been approved in the US by the time of this study, patients who were very or extremely fearful of needles would likely have been receiving an oral rather than injectable DMD.

Among patients in the fourth quartile of written SDMT score (indicating less cognitive disability), there was a preference for the reusable device, suggesting that these patients were not impeded by the steps of assembly, especially if they were already habituated to them. Overall, 49.0% strongly agreed that they were satisfied with the number of steps needed to complete an injection with the single-use autoinjector versus 31.3% for the reusable device; it remains to be seen whether a population including more patients with higher levels of cognitive disability might have found the single-use autoinjector preferable for its fewer steps required.

A limitation of this study is that the UTQ did not include any open-ended questions regarding device preference; such questions can be useful for eliciting fuller, more in-depth responses and for highlighting issues that may have not been covered in other questions. Additionally, the Baseline Characteristics Questionnaire and UTQ were developed specifically for this study and have not been validated psychometrically. Furthermore, limiting enrollment to treatment-naïve patients would have provided the clearest basis for comparison between devices without introducing device bias due to familiarity. However, because the majority of patients receiving IFN β-1a 44 μg SC tiw are already using an autoinjector, we enrolled patients with previous experience to alleviate the recruitment barrier. More subjects (46.4%) had most recent previous experience with the reusable autoinjector, compared with manual injection with PFS (29.9%) and the single-use autoinjector (23.7%). This could have introduced the potential for bias; as seen in the results, patients were more likely to favor the device with which they had prior experience. Subgroup analyses were conducted to evaluate the relevance of previous experience, although these were limited by small numbers of patients.

This study required patients to self-inject their DMD, and this ability was reflected in the low levels of anxiety regarding self-injection found by the baseline questionnaire. Therefore, this study does not provide any data on autoinjector preferences among patients who are unable to self-inject, for example, because of visual impairment or reduced upper limb function and manual dexterity. Likewise, this study does not provide any data on the views of caregivers. Further studies are required to explore the needs of more severely disabled patients and their caregivers.

5. Conclusions

Responses indicate differences in satisfaction between devices; however, both were found easy or very easy to use by most patients. Patients were more likely to rate each device as easy or very easy to use if they had previous experience with it, suggesting habit plays a role in preference. Having two autoinjector options may offer the potential to accommodate patient preferences. Information from this study may assist the health-care provider in identifying patients who are more likely to find one device more suitable over another. Ease of administration and patient satisfaction relates to adherence; therefore, patients who are satisfied with their DMD device may be more likely to adhere to treatment.

Declaration of interest

S Wray acted as a consultant for Biogen, Genentech/Roche, Genzyme/Sanofi, Novartis, and Teva; and received research funding from Alkermes, Biogen, EMD Serono, Inc. (a business of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany), Genzyme, Novartis, Receptos, Roche/Genentech, and TG Therapeutics. B Hayward is an employee of EMD Serono, Inc., Billerica, MA, USA (a business of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). F Dangond is an employee of EMD Serono, Inc., Billerica, MA, USA (a business of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). B Singer acted as a speaker and/or consultant for Acorda, Bayer, Biogen, EMD Serono, Inc. (a business of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany), Genentech, Novartis, Sanofi-Genzyme, and Teva; and has received research funding from Acorda, Biogen, Genzyme, MedImmune, Novartis, and Roche. Medical writing assistance was utilized in the preparation of this paper, carried out by Reza Sayeed and Robert Coover of Caudex (supported by EMD Serono, Inc., Rockland, MA, USA [a business of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany]) in the form of editorial assistance in drafting the manuscript, collating the comments of authors, and assembling tables and figures. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose

F1_Wray_REDEFINE_Exp_Opin_Drug_Deliv_SuppMat.docx

Download MS Word (175.4 KB)Acknowledgments

MusiQoL contact information and permission to use: Mapi Research Trust, Lyon, France. Email: [email protected] – Internet: www.Mapi-trust.org or [email protected] or [email protected]. The REDEFINE trial was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (identifier, NCT02019550). The design of this trial was presented at the Annual Meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers (CMSC) and the Sixth Cooperative Meeting with Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ACTRIMS), May 28–31, 2014, Dallas, TX, USA; preliminary results were presented at the 2016 Annual Meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers (CMSC), June 1–4, 2016, National Harbor, MD, USA; and final results were presented at the 32nd Congress of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ECTRIMS), September 14–17, 2016, London, UK. The data that support the findings of this study are available from EMD Serono, Inc., Rockland, MA, USA (a business of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) but restrictions apply to the availability of these data. These restrictions and application process are detailed in EMD Serono’s Responsible Data Sharing Policy available at http://www.emdserono.com/en/research/commitment_to_responsible_clinical_trial_data_sharing/commitment_to_responsible_clinical_trial_data_sharing.html

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Wray S, Armstrong R, Herrman C, et al. Results from the single-use autoinjector for self-administration of subcutaneous interferon beta-1a in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis (MOSAIC) study. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2011;8:1543–1553.

- Lugaresi A, Durastanti V, Gasperini C, et al. Safety and tolerability in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients treated with high-dose subcutaneous interferon-beta by Rebiject autoinjection over a 1-year period: the CoSa study. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2008;31:167–172.

- Devonshire V, Lapierre Y, MacDonell C, et al. The Global Adherence Project - a multicentre observational study on adherence to disease-modifying therapies in patients suffering from relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2006;12(Suppl. 1):S229–S243.

- Simeoni M, Auquier P, Fernandez O, et al. Validation of the Multiple Sclerosis International Quality of Life questionnaire. Mult Scler. 2008;14:219–230.

- Devonshire V, Arbizu T, Borre B, et al. Patient-rated suitability of a novel electronic device for self-injection of subcutaneous interferon beta-1a in relapsing multiple sclerosis: an international, single-arm, multicentre, Phase IIIb study. BMC Neurol. 2010;10:28.

- Singer B, Wray S, Miller T, et al. Patient-rated ease of use and functional reliability of an electronic autoinjector for self-injection of subcutaneous interferon beta-1a for relapsing multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Related Disord. 2012;1:87–94.

- Bayas A, Ouallet JC, Kallmann B, et al. Adherence to, and effectiveness of, subcutaneous interferon beta-1a administered by RebiSmart® in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis: results of the 1-year, observational SMART study. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2015;12:1239–1250.

- Boeru G, Milanov I, De RF, et al. ExtaviJect® 30G device for subcutaneous self-injection of interferon beta-1b for multiple sclerosis: a prospective European study. Med Devices (Auckl). 2013;6:175–184.

- Hupperts R, Becker V, Friedrich J, et al. Multiple sclerosis patients treated with intramuscular IFN-beta-1a autoinjector in a real-world setting: prospective evaluation of treatment persistence, adherence, quality of life and satisfaction. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2015;12:15–25.

- Lugaresi A, De RF, Clerico M, et al. Long-term adherence of patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis to subcutaneous self-injections of interferon beta-1a using an electronic device: the RIVER study. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2016;13:931–935.

- Masid ML, Ocana RH, Gil MJ, et al. A patient care program for adjusting the autoinjector needle depth according to subcutaneous tissue thickness in patients with multiple sclerosis receiving subcutaneous injections of glatiramer acetate. J Neurosci Nurs. 2015;47:E22–E30.

- Pozzilli C, Schweikert B, Ecari U, et al. Quality of life and depression in multiple sclerosis patients: longitudinal results of the BetaPlus study. J Neurol. 2012;259:2319–2328.

- Willis H, Webster J, Larkin AM, et al. An observational, retrospective, UK and Ireland audit of patient adherence to subcutaneous interferon beta-1a injections using the RebiSmart((R)) injection device. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2014;8:843–851.

- D’Arcy C, Thomas D, Stoneman D, et al. Patient assessment of an electronic device for subcutaneous self-injection of interferon beta-1a for multiple sclerosis: an observational study in the UK and Ireland. Patient Pref Adherence. 2012;6:55–61.

- Weller I, Saake A, Schreiner T, et al. Patient satisfaction with the BETACONNECT autoinjector for interferon beta-1b. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:951–959.

- Ziemssen T, Sylvester L, Rametta M, et al. Patient Satisfaction with the New Interferon Beta-1b Autoinjector (BETACONNECT). Neurol Ther. 2015;4:125–136.

- Mikol D, Lopez-Bresnahan M, Taraskiewicz S, et al. A randomized, multicentre, open-label, parallel-group trial of the tolerability of interferon beta-1a (Rebif®) administered by autoinjection or manual injection in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2005;11:585–591.

- Phillips JT, Fox E, Grainger W, et al. An open-label, multicenter study to evaluate the safe and effective use of the single-use autoinjector with an Avonex® prefilled syringe in multiple sclerosis subjects. BMC Neurol. 2011;11:126.

- Seddighzadeh A, Hung S, Selmaj K, et al. Single-use autoinjector for peginterferon-beta1a treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: safety, tolerability and patient evaluation data from the Phase IIIb ATTAIN study. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2014;11:1713–1720.

- Brochet B, Lemaire G, Beddiaf A. [Reduction of injection site reactions in multiple sclerosis (MS) patients newly started on interferon beta 1b therapy with two different devices]. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2006;162:735–740. French.

- Cramer JA, Cuffel BJ, Divan V, et al. Patient satisfaction with an injection device for multiple sclerosis treatment. Acta Neurol Scand. 2006;113:156–162.

- de Sá J, Urbano G, Reis L. Assessment of new application system in Portuguese patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26:2237–2242.