ABSTRACT

Pregnancy is an opportune time for women to make healthy changes to their lifestyle, however, many women struggle to do so. Multiple reasons have been posited as to why this may be. This review aimed to synthesise this literature by identifying factors that influence women’s health behaviour during pregnancy, specifically in relation to dietary behaviour, physical activity, smoking, and alcohol use. Bibliographic databases (MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL-P, MIDIRS) were systematically searched to retrieve studies reporting qualitative data regarding women’s experiences or perceptions of pregnancy-related behaviour change relating to the four key behaviours. Based on the eligibility criteria, 30,852 records were identified and 92 studies were included. Study quality was assessed using the CASP tool and data were thematically synthesised. Three overarching themes were generated from the data. These were (1) A time to think about ‘me’, (2) Adopting the ‘good mother’ role, and (3) Beyond mother and baby. These findings provide an improved understanding of the various internal and external factors influencing women’s health behaviour during the antenatal period. This knowledge provides the foundations from which future pregnancy-specific theories of behaviour change can be developed and highlights the importance of taking a holistic approach to maternal behaviour change in clinical practice.

Introduction

Pregnancy is a period of time when women may be more receptive to health promotion and experience increased motivation to make healthy changes to their lifestyle (Lindqvist et al., Citation2017; O’Brien et al., Citation2017). As such, it has been suggested that this period may be a ‘teachable moment’ (Phelan, Citation2010). McBride et al. (Citation2003) define teachable moments as significant health events that may motivate an individual to adopt risk-reducing health behaviour(s). They argue that an effective teachable moment is cued by a health event that increases personal perception of risk and outcome expectations, provokes a strong emotional response, and causes a redefinition of self-concept or social role. Based on this model, pregnancy has the potential to act upon each of these psychological domains, creating a salient opportunity for change (Phelan, Citation2010).

Encouraging women to adopt healthy behaviours during pregnancy has the potential to reduce the risk of pregnancy-related conditions such as preeclampsia and gestational diabetes (Yang et al., Citation2019), as well as the risk of obstetric complications such as pre-term birth, caesarean birth, miscarriage, and stillbirth (Escañuela Sánchez et al., Citation2019; Liu et al., Citation2020; Sundermann et al., Citation2019; Yang et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, healthy behaviours developed during pregnancy have the potential to be maintained into the postnatal period and beyond, improving the health of women, as well as their children, who may otherwise emulate poor behaviours (Yelverton et al., Citation2020; Zarychta et al., Citation2019) or develop health conditions related to maternal risk factors (Edlow, Citation2017; Gutvirtz et al., Citation2019; Heslehurst et al., Citation2019; Stacy et al., Citation2019; Zhang et al., Citation2020).

Current UK guidelines recommend that women are provided with lifestyle advice during antenatal appointments, including information on smoking cessation, alcohol consumption, exercise, and diet/nutrition (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, Citation2008). These four behaviours are particularly important as they are key modifiable behavioural risk factors for adverse pregnancy outcomes and lifelong non-communicable diseases, which also place the highest economic burden on the NHS (Hayes et al., Citation2021; Scarborough et al., Citation2011; World Health Organisation, Citation2020). Intervening early in pregnancy and supporting women to make changes to these behaviours may therefore improve the trajectory of health outcomes for both the mother and child, as well as reducing the associated burden on the health service.

The antenatal period provides a valuable opportunity for health professionals to intervene and address poor health behaviours, particularly because women are likely to have increased contact with health professionals during this time. Unlike other teachable moments in acute health settings, pregnancy typically provides a window of opportunity spanning up to 40 weeks, involving multiple contacts between women and health professionals (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, Citation2008). However, behavioural interventions that have been trialled in antenatal settings are frequently unsuccessful at changing the target behaviour or affecting primary outcomes (Coleman et al., Citation2012; Dodd et al., Citation2008; Kennelly et al., Citation2018). This is particularly true for groups of women who may receive greater benefit from such intervention, such as those with raised BMIs, for example (Dodd et al., Citation2014; Poston et al., Citation2015).

A commonality of ineffective behavioural interventions is that they are often not underpinned by theoretical concepts (Brown et al., Citation2012; Currie et al., Citation2013; Flannery et al., Citation2019). Using theory in intervention development is necessary in order to target causal factors of behaviour, and to understand methods of change and the pathways through which change may occur (Bartholomew & Mullen, Citation2011; Michie et al., Citation2008). However, there is currently no theoretical model of behaviour change specific to pregnancy. Whilst more general models may be applied to the antenatal context, pregnancy is a unique health event that requires an understanding that is specific to the experience. This is not least because pregnancy is a physiological event, as opposed to a pathological process, that is associated with psychological changes. It is also unique in that it requires decision-making about the life of another individual. From the mother’s perspective, pregnancy involves engaging with an ordered health care plan, and invokes societal expectations about behaviour, meaning pregnancy is a health event unlike any other.

In order to work towards a goal of developing a relevant pregnancy-specific theory of behaviour change, it is necessary to first understand the mechanisms underlying women’s decisions about their health behaviour. Whilst many studies have sought to do this, a qualitative review of these studies, focusing on multiple health behaviours, does not exist.

Qualitative research can provide an understanding of women’s perspectives and lived experiences that cannot be captured using quantitative methods alone (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019). Reviewing and thematically synthesising this literature allows for the development of a richer interpretation and conceptual understanding that goes beyond the findings of individual studies, producing novel findings that are greater than the sum of its parts (Barnett-Page & Thomas, Citation2009; Evans & Pearson, Citation2001; Flemming & Noyes, Citation2021). A scoping review of the literature revealed a plethora of qualitative research, confirming our supposition that a qualitative review would be the most appropriate method to address the research question.

This review aims to systematically search and synthesise the existing qualitative literature to identify factors influencing health behaviour change during pregnancy, specific to dietary behaviour, physical activity, smoking, and alcohol use.

Methods

This review has been conducted and reported in line with the PRISMA guidelines (Moher et al., Citation2009) and ENTREQ guidance for reporting qualitative syntheses (Tong et al., Citation2012) (see Supplementary Material, S1 and S2). The review protocol was registered in PROSPERO on 10 January 2019 (CRD42019119302).

Eligibility

Studies were included if they reported any qualitative data about women’s experiences or perceptions of pregnancy-relatedFootnoteI behaviour change, specifically; dietary behaviour, physical activity, smoking, and alcohol use. Studies were eligible for inclusion if they included participants who were over 18 years old and pregnant, or less than 2 years postnatal (providing retrospective data). Journal articles, university dissertations and theses, and unpublished reports were included.

Studies from low- or middle-income countries were excluded (based on the list provided by the World Bank, Citation2019), as were those including women on specialist care pathways for a medical diagnosis (e.g., gestational diabetes), or women who had previously experienced pregnancy complications (as reported by study authors), unless these women were differentiable from the participants of interest. Studies including women deemed to be of high-risk status who were advised not to engage in a behaviour of interest (as reported by study authors) were also excluded (e.g., women advised bed rest for threatened preterm labour or recurrent vaginal bleeding), unless these women could also be differentiated from the population of interest. These exclusion criteria were applied to reduce the variance in advice provided in relation to the health behaviours of interest (see Supplementary Material, S3, for full eligibility criteria).

Search strategy

MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL-P, and MIDIRS were searched on the 11 December 2018 (and updated on 2 September 2020). The search strategy used was tailored according to the indexing rules of each database. Terms were combined using Boolean operators. Truncation and Wild Cards were used to find variations of original search terms. Where possible, MeSH Headings were also used. No restrictions were placed on language or publication date (see Supplementary Material, S4, for the search strategy used).

Study selection

Records retrieved by the searches were imported into Endnote reference management software version X8.0.1 (Clarivate, Citation2016) and duplicates were removed. To ensure internal consistency in the application of the eligibility criteria, LR and DS both independently screened 10% of all titles, then discussed and refined the eligibility criteria. This process was repeated four times. An agreement level of 99.7% was reached for the final 10% of titles screened. The refined eligibility criteria were then used by LR to screen the remaining titles and abstracts of all records. Full-text screening was conducted by LR, with 10% of the records also screened by SP. An agreement level of 100% was reached. Reference lists of included studies were searched for other relevant studies, and Google Scholar was used to search all citing articles for additional relevant studies. Grey literature was searched using Open Grey and Jisc Library Hub Discover, as well as searching for publications of key authors.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data from included studies were extracted using a data extraction tool specifically designed for this study. All text within the ‘results’ or ‘findings’ section was treated as data (see Supplementary Material, S5, for further details of extracted data items). Authors were contacted for further information where necessary. Study quality was assessed using a modifiedFootnoteII version of the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme qualitative appraisal checklist (CASP; Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, Citation2018). Assessment of all included studies was conducted by LR, with 10% assessed by DS over two rounds to clarify assessment criteria. 100% agreement on the quality assessment of those studies was reached. No papers were excluded based on quality, as there is limited evidence to suggest this is beneficial (Carroll et al., Citation2012; Dixon-Woods et al., Citation2007; Long et al., Citation2020). However, the assessment process allows for transparency and enhances our understanding of the contribution made by each study to the findings and conclusions of the review.

Data synthesis

Data extracted from the results/findings sections of the included studies were analysed using thematic synthesis (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008). An inductive approach was taken and initially LR and DS conducted line-by-line coding of papers containing references to dietary behaviour. Both author interpretations and participant quotes were coded. Papers addressing dietary behaviour were coded first. Descriptive and higher-order themes were then developed following discussion and joint interpretation of the data.

This thematic framework was then used to guide the analysis of the papers containing references to physical activity, smoking, and alcohol use. The data were coded inductively, and these initial codes mapped onto the existing thematic framework. Additional codes were developed where necessary. Coding was conducted separately for each behaviour by the lead author. Analysis was conducted using NVivo 12 Plus (QSR International Pty Ltd, Citation2018). A breakdown of the studies containing data pertaining to each health behaviour is reported in the Supplementary Material (see S6).

Results

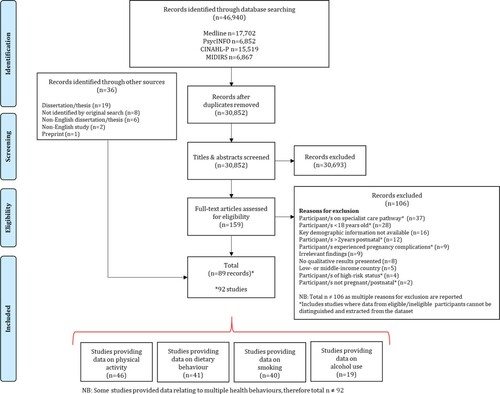

After removing duplicates, 30,852 records were screened for eligibility, based first on title and abstract, and then on full-text. A total of 89 records were eligible for inclusion. Three theses contained two studies each, giving a total of 92 studies included in this review (see , Supplementary Material, S7). Forty-six studies contained data on physical activity, 41 on dietary behaviour, 40 on smoking, and 19 on alcohol use.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram of included studies, adapted from Moher et al. (Citation2009).

Included studies were journal articles (n = 62, 67%), dissertations/theses (n = 29, 32%), and a research report (n = 1, 1%), published between 1990 and 2020. Studies comprised 1889 participants,FootnoteIII although data from some of these participants has been excluded, as per the eligibility criteria. Most studies were conducted in the United Kingdom (n = 39, 42%). 59% (n = 54) of studies included participants in the antenatal period only, 28% (n = 26) included both antenatal and postnatal participants, and 13% (n = 12) included only those in the postnatal period. Where reported, most studies included both nulliparous and multiparous women (n = 52, 57%). Interviews were the most common method of data collection (n = 79, 86%), and where described, thematic analysis was the most frequently used analysis method (n = 26, 28%) (see Supplementary Material, S8, S9).

There was notable variation in quality between studies. In particular, many studies failed to discuss the role of the researcher and any consideration of the impact that may have on data generation or interpretation (n = 64, 70%). Over a quarter of studies did not provide an appropriate rationale for the methods/design used (n = 28, 30%), or provide sufficient detail about the data collection process (n = 24, 26%). Just under a quarter of studies also failed to clearly report the data analysis process (n = 21, 23%) (for full details of quality assessment for each study see Supplementary Material, S10).

Three overarching themes, and nine sub-themes were generated (see ). The main themes are entitled ‘A time to think about 'me'', ‘Adopting the 'good mother' role', and ‘Beyond mother and baby’. All four health behaviours are discussed concurrently. Author comments and participant quotes are presented within the text to illustrate the themes (see for additional author comments and illustrative quotes). Both author interpretations and participant quotes reflect women’s perspectives and experiences, and as such, the findings have been reported according to this perspective. Additional detail pertaining to the barriers and facilitators identified within the analysis is provided in the Supplementary Material (see S11).

Table 1. Illustrative author comments and/or participant quotes for each health behaviour.

A time to think about ‘me’

The first theme relates to women’s desire to think about their own mental and physical needs during pregnancy. During this period women held a desire to self-indulge (1.1), to retain ownership over their body and behaviour (1.2), and for good health (1.3), all of which affected their motivation to make health behaviour changes in both positive and negative ways.

A desire to self-indulge

Women reported a desire to indulge themselves throughout their pregnancy, in relation to all four behaviours. For some women, this desire encouraged the maintenance or uptake of healthy behaviours such as physical activity. Engaging in physical activity was viewed by some as an opportunity to do something for themselves and as a behaviour that provided some ‘me time’41. Some women also viewed physical activity as a physical ‘need’63.

…exercise is a time for you to be completely selfish in yourself and just think about you […] you can focus on your own body, you’re alone with your own thoughts (Participant quote41)

However, the desire to self-indulge sometimes encouraged poorer health behaviours such as continuing to smoke or consume alcohol.FootnoteIV These behaviours were reported to be pleasurable activities or a ‘treat’29, 33, 73, although this desire was sometimes driven by physical addition. Similarly, women also reported a desire to ‘reward’3, 62 themselves and relax their approach towards their eating during this time. Pregnancy was perceived by some women to be a period when normal rules and expectations around food consumption eased, allowing them to indulge without the consequence or judgement normally afforded to them. Some women also talked about being ‘exempt’74a from dieting and from seeking the slim body ideal that many women aspire to achieve. For some, excess weight gain was viewed as inevitable, which also encouraged poorer dietary behaviours.

Pregnancy appears to prescribe increased food intake, relaxing women’s behaviours from ‘guilt-eating’ to self-indulgence, in keeping with the ‘eating for two adage’ (Author comment83)

A desire to retain ownership over body and behaviour

Women wanted to retain control and ownership over the decisions they made about all four health behaviours. Some were resistant to being told what to do and dismissive of advice from professionals (e.g., midwifes and GPs), and family and friends. Women were particularly quick to question guidelines surrounding alcohol use, due to the conflicting nature of the advice provided. Some dismissed guidelines as open to interpretation and/or irrelevant to them as they did not consume what they perceived to be harmful levels of alcohol. Likewise, some women believed their current activity levels were appropriate and therefore did not need to increase, or in some cases reduce, their activity to recommended levels. All behaviours were viewed as a matter of personal choice, but this was most pronounced for smoking and alcohol use. Decision-making was also sometimes based on a compensatory rationale; for example, choosing to continue drinking because they had sacrificed other pleasurable behaviours, such as smoking tobacco or marijuana.

Oh, well, at the end of the day I could eat healthy, I just choose not to. It’s really up to you on what you eat (Participant quote59)

Instead of following guidance, some women preferred to respond intuitively to what they perceived to be their body’s, or baby’s, needs. Whilst this sometimes resulted in healthy behaviours, such as maintaining existing exercise routines, it sometimes meant making poorer food choices, continuing to consume alcohol, and/or reducing physical activity.

…although they considered the antenatal physical activity guidelines to be helpful […] they did not let these messages take preference over the signals their own body was giving them. They trusted their own body more than the guidelines and showed resistance toward being told what to do (Author comment84)

Some women were motivated to increase, or maintain, healthy eating or exercise behaviour in an attempt to navigate their changing bodies and assert control over their weight gain. In some cases, smoking was also used as a tool to control appetite and aid weight loss/control. For some women, this was driven by a fear of how they might look or feel if they were to gain an excessive amount of weight. The challenge of losing weight postnatally was also a concern, especially for those who had previously experienced postnatal weight retention.

A desire for good health

Pregnancy symptoms were reported to impact upon all four health behaviours to some extent. Nausea and increased sensitivity to smell and taste sometimes restricted smoking and alcohol use. Many modified their dietary behaviour, often, but not always, in an unhealthy way, in an attempt to manage feelings of nausea or sickness, due to food cravings, or due to changes in appetite or food preferences. Backache, lower body pain, and fatigue also restricted some women’s ability and willingness to engage in physical activity. However, these symptoms were sometimes alleviated by adopting a healthier diet or becoming more active.

Pregnancy changes are not always good changes are they. People get tired, you get headaches, leg pains and backache and I think those sorts of things make people think you shouldn’t exercise but for me the opposite is true (Participant quote41)

Beyond their immediate pregnancy symptoms, women considered the positive impact of making behavioural changes on their overall health, in relation to all four behaviours. However, the perceived benefits of continuing to smoke or drink alcohol sometimes outweighed the perceived benefits of reducing these behaviours. Some women were hopeful that making healthy changes to their diet and activity levels might increase the likelihood of experiencing an uncomplicated pregnancy and/or birth, and giving birth to a smaller baby. However, some women’s concerns about their health meant they were deterred from physical activity, as they reported being keen to protect themselves and avoid injury. Considering the benefits to their future health also acted as a driver to change. For example, some women reported a desire to improve their dietary behaviour in order to protect their future health and future pregnancies. Maintaining or increasing physical activity was perceived by some to aid with recovery after childbirth and enable them to be physically active again, sooner, postnatally. Some women also discussed their future intentions to quit smoking.

Women’s mental health and emotional state also impacted on their motivation to make changes to all four behaviours, to various extents. Smoking and alcohol use in particular were sometimes used as coping mechanisms and as such, reducing these behaviours could be viewed as potentially anxiety-inducing or stressful. Negative emotions such as boredom, stress, and frustration also drove unhealthy eating, as for some, this behaviour was a source of comfort to sate emotional needs. For some smokers, their perception of whether the changes were permanent or temporary also impacted upon their motivation.

Women expressed a wish to escape from reality and problems in their lives and cigarettes and alcohol appeared to offer them this escape (Author comment1)

Conversely, having a positive attitude and high levels of confidence and self-efficacy improved some women’s ability to reduce their alcohol consumption, smoking, and/or increase their physical activity levels. Women reported experiencing a positive impact on their mental health and wellbeing as a result of making changes to their smoking and physical activity, which in turn acted as motivation to continue making healthy changes. Physical activity was also perceived by some to help prepare them psychologically for childbirth.

Adopting the ‘good mother’ role

Women were keen to fulfil the ‘good mother’ role. This was driven by the health of the baby (2.1), by roles and expectations (2.2), and by women’s pre-pregnancy attitudes and behaviours (2.3). The focus on them as a mother was distinct to the focus on them as an individual and as such, some women experienced feelings of guilt when their desires and behaviours misaligned. Counterintuitively, these feelings of guilt sometimes increased the desire to smoke. Whilst some women adopted behavioural changes automatically, or with relative ease, for others, these changes were more deliberate or sacrificial, sometimes only occurring once the pregnancy felt more ‘real’ or became physically noticeable, giving a sense of connection to the baby. Conversely, feeling disconnected from the pregnancy acted as a barrier to changing smoking behaviour in some instances.

Driven by the health of the baby

Motivation to make healthy changes was often driven by the desire to ensure the health of the baby and to minimise any risks. Women talked about creating ‘the best conditions’3 for carrying a baby by eating healthily and ensuring they consumed nutritious food for the baby’s benefit. However, concern about risk to the baby sometimes acted as a barrier to changing behaviour, particularly in relation to physical activity. This was especially true for women who had previously experienced a miscarriage or other difficulties. Similarly, some women chose to maintain smoking or alcohol use, and reported believing that cessation may harm the baby in some way, either through nicotine withdrawal, or harm associated with negative maternal mental health.

Participants described how their unborn child’s interests were first and foremost in their minds. These women revealed feeling an obligation to protect their child’s health and safety. ‘I’ve got to think of my child, I’ve got to put them first’ (Author comment/participant quote71)

Women described a sense of responsibility, not only towards their baby, but to themselves, their partner, and family, which provided motivation for change. For some women who attempted to reduce smoking or increase levels of physical activity, receiving positive feedback on their baby’s health whilst attending antenatal scans and tests provided reassurance and further motivation to continue making healthy changes. However, confirmation of a healthy scan or test result also supported some women’s decisions to continue to smoke, drink alcohol, and eat unhealthily.

…as her pregnancy progressed and they were assured from scans and the midwife their baby was healthy, they felt able to have crisps each day or chocolate. ‘ …I’m getting closer to the end, and it sounds a bit awful in some ways, but what difference does it make now because the baby is healthy’ (Author comment/participant quote74a)

Driven by roles and expectations

For some women, it was important to adhere to what they perceived to be the role of a ‘good mother’, by eating healthily, stopping drinking, ceasing smoking, and/or staying physically active. However, some women continued to drink alcohol based on the idea that retaining their identity, and thus alcohol consumption, enabled them to become good mothers. For some women, changes they made to their smoking and drinking behaviour, were due, in part, to societal pressures and expectations. Women reported feeling under surveillance throughout their pregnancy and the stigma and feeling of judgement associated with making unhealthy choices motivated some women to adjust their behaviour. Societal expectations to eat more healthily during pregnancy were also reported.

Yvette highlighted a sense of surveillance, saying that she felt like people were ‘watching me’ to ensure that she acted like a ‘good’ responsible mother (Author comment29)

However, feelings of stigma and judgment also encouraged some women to conceal their behaviour, and in some cases, women’s smoking habits increased as a response to external pressure. Interestingly, some women also reported feeling judged for exercising, despite it being an objectively healthy behaviour, as pregnancy was often perceived by others to be a time when women should reduce their activity levels. This is in contrast to the idea that maintaining physical activity adheres to the ‘good mother ideal’, as discussed above, suggesting there is a lack of clarity as to what is considered a safe or appropriate level of activity during pregnancy. Whilst this acted as a barrier for some, others rejected this notion and were determined to disprove existing stereotypes. This attitude was shared by some of the women who continued to drink alcohol in moderation, refusing to adhere to the idea that this made them any less responsible as mothers.

No, I generally didn’t do it in public […] I would wait till I got home and I would smoke out the back at home so no one could see me. I wouldn’t do it in public because I didn’t want to [sighs], um I had people – I had a lady look at me funny and I felt really bad (Participant comment89)

Driven by pre-pregnancy attitudes and behaviours

The extent to which women changed their behaviour and adopted the ‘good mother’ role was partly influenced by women’s pre-pregnancy lifestyles, their attitudes, and the relationships they had with the respective health behaviours prior to pregnancy. For some women, changing their behaviours meant losing part of their pre-pregnancy identity. Women who had pre-established healthy habits and routines were more likely to maintain these throughout the pregnancy, which was true for all behaviours. The converse also applied. Established beliefs and intentions that women held about making behavioural changes once pregnant also affected their decision-making. Women reported pre-pregnancy intentions to reduce smoking and alcohol use, as well as physical activity.

…by the time I got pregnant I had quite strong opinions on what I thought was appropriate and what I didn’t …we made our decisions quite quickly and easily just on previous or prior knowledge (Participant quote51)

Parity also affected attitudes towards behavioural change. Nulliparous women were sometimes more cautious than their multiparous counterparts in relation to alcohol use and physical activity. However, multiparous women sometimes made healthy changes in subsequent pregnancies where their behaviour had previously resulted in negative health outcomes for either themselves or an existing child. Conversely, women who had previously experienced a healthy pregnancy despite unhealthy behaviours were often less motivated to make behavioural changes in subsequent pregnancies. For both nulliparous and multiparous women, difficulty conceiving, or experience of a prior miscarriage, could sometimes act to encourage a reduction of physical activity, smoking and alcohol use.

All the smokers in the interview survey cut down except for 20-year-old Ruth, […] ‘It’s a load of poppy-cock, she (her child) was nine and a quarter pounds and I smoked 30 a day when I was carrying her' (Author comment/participant quote86)

Beyond mother and baby

Beyond the immediate experience of the mother and baby, various external influences affected women’s decision-making about their health behaviour. These included practical and environmental influences (3.1), social influences (3.2), and knowledge, understanding, and advice (3.3).

Practical and environmental influences

Environment played a role in influencing women’s decision-making in relation to all four health behaviours. Being in settings that promoted unhealthy behaviours, or that provided easy access to unhealthy foods or cigarettes, acted as a barrier to behaviour change for some women. Conversely, availability of healthy food options facilitated healthy choices. Being unfamiliar with the local area and having to rely on transportation rather than walking sometimes restricted potential for physical activity, as did the weather, which was also reported to affect dietary behaviour.

Inaccessibility of pregnancy-appropriate exercise classes and places to be active was another barrier to physical activity for some women. Accessibility of smoking cessation services was similarly important; lack of access, in terms of inconvenient times and locale of appointments, impacted on some women’s ability to attend. The cost of healthy food and gym memberships was an additional barrier for some women to change their behaviour, whilst the cost of cigarettes and alcohol (and potential for saving money) sometimes motivated a reduction in these activities. Interestingly, smoking was used by some women as a way to save money on food, due to it acting as an appetite suppressant.

One thing that discourages me is it [physical activity] is expensive. So I think a lot of maybe [sic] if there were options out there that didn’t cost money because the recreation centre is expensive and day care is expensive (Participant quote55)

Time constraints and competing priorities, such as work or existing childcare responsibilities, were cited as barriers to physical activity, healthy eating, and smoking cessation. Some women perceived healthy meals as time-consuming to prepare and therefore embraced the convenience of pre-prepared food, takeaways, or eating out at restaurants. Being from a socially disadvantaged background, poor living conditions, and frequent relocations were also cited as factors affecting sustained smoking habits and alcohol use. Similarly, for economically-deprived women relying on donations, availability of food also affected some women’s dietary behaviour.

I really don’t decide right now because, um, I’m staying at a family shelter, and so they kind of feed us (Participant quote59)

Social influences

Social support and the influence of others acted as both a barrier and facilitator, across all four behaviours. Supportive partners were reported to play an instrumental role in women’s behaviour change efforts; however, partners’ dietary behaviour, physical activity levels, smoking habits, and alcohol use all had the potential to act as significant barriers where they were unhealthy. The support of friends, family, and work colleagues was also reported to facilitate behaviour change, however some women reported experiencing pressure from others to smoke, consume alcohol, or to ‘eat for two’. This is in contrast to women’s experiences of societal pressure and expectations to maintain healthy behaviours, as discussed previously.

She [mom] gave me the portion. I was like, ‘Whoa, this is a lot.’ She was like, ‘Oh, you’re eating for two! It’s not that much’ (Participant quote72)

The social nature of eating, smoking, and alcohol use, and being a part of social networks where smoking and drinking were social norms, could make behaviour change more difficult. Avoidance of such social situations facilitated healthy changes. However, women described feeling isolated when they chose to abstain from smoking or drinking, which could impact negatively on relationships where this had once been a shared activity. Conversely, the social nature of physical activity facilitated this behaviour for some women. Pregnancy specific classes were highly valued and provided women with a chance to see other pregnant women modelling positive behaviour.

Their social network has contributed to the continuation of the use of cigarettes and alcohol. One participant stated that a friend has influenced her to continue with her habits and avoiding them has been so difficult (Author comment1)

Other women’s health behaviour during pregnancy was often used as a ‘yard-stick’ for one’s own choices. Across all behaviours, women used others’ experiences to justify their own behaviours, based on either positive or negative health outcomes that they attributed to a women’s behaviour during pregnancy.

Knowledge, understanding, and advice

Across all behaviours, knowledge and understanding was an important factor affecting decision-making. Whilst some women were aware of the importance of making healthy changes, and had the skills and knowledge necessary to do so, some women lacked an understanding about potential harm to the baby, held misconceptions that justified their behaviour, and lacked appropriate knowledge. Some women appeared to perceive there to be a hierarchy of health behaviours, whereby it was more important to modify certain behaviours over others.

I think that the not eating too much junk was a higher priority than going swimming or whatever, or you know just doing some type of physical activity, even though I know they go hand in hand (Participant quote67)

Women reported receiving informational support from health professionals about all four health behaviours, however, women’s level of engagement with advice about smoking and dietary behaviour appeared to be affected by the quality of the patient-provider relationship. Having advice about dietary behaviour delivered by a midwife, as well as continuity of care, was also reported to be of value. However, some women reported feeling rushed during appointments with health professionals and reported a lack of informational support and discussion about behaviour change. Information provided by health care professionals and official guidance (e.g., from healthcare providers) about diet, physical activity, and alcohol use, was perceived to be restrictive, and a ‘one-size-fits-all’29 approach, with little appreciation for individual differences, or differing cultures and demographic backgrounds. Information about smoking and alcohol use, in particular, was perceived to be conflicting and inconsistent. Some health professionals exacerbated this issue by providing advice that was contradictory to ‘official’ guidance.

…I tried to cut down to quit [smoking], no good. I spoke to my ob [obstetrician] and he said that the baby would already be used to it and he really didn’t believe that it caused all that much damage (Participant quote89)

Faced with conflicting or inconsistent information from professionals, women often sought information from other sources (e.g., books, the internet) and relied upon lay advice to inform their decision-making. Some women also adhered to cultural beliefs about which foods should be included in their diet and about appropriate levels of physical activity during pregnancy.

Discussion

This review identified three overarching themes which encompass factors that can influence behaviour change during pregnancy. Whilst there is variability in the extent to which each of the individual factors relate to dietary behaviour, physical activity, smoking, and alcohol use, there are clear commonalities, and the overall themes and sub-themes provide a level of explanation that is relevant across these behaviours.

Findings reveal that pregnancy is a time when women think about themselves and their own needs, rather than exclusively focusing on those of their unborn child. Women reported feeling exempt from societal beauty standards, in relation to their body size and shape, and for some this led to indulgence in high-calorie, low-nutrient dense food. This is consistent with findings reported elsewhere in the literature (Hodgkinson et al., Citation2014; Stockton & Nield, Citation2020). Accordingly, women were keen to retain control and ownership over their decision-making, rather than passively accepting advice and guidelines that might suggest pleasurable behaviours should be limited. Previous research has highlighted the role of control in relation to the changing maternal body (Hodgkinson et al., Citation2014), which was also evident in this review, however, fewer studies have discussed the role of control as related to behaviour and decision-making.

Distinctively, pregnancy was also viewed as a time to adopt the role of the ‘good mother’, often by making healthy lifestyle changes. This shift in identity is consistent with McBride et al.’s (Citation2003) model, which suggests that redefinition of self-concept or social role is a key construct underlying teachable moments. The ‘good mother’ concept has been discussed at length in the literature, although more frequently in relation to the postnatal period (Goodwin & Huppatz, Citation2010; Johnston & Swanson, Citation2003; Marshall et al., Citation2007; Pedersen, Citation2016). Our findings extend this concept to the antenatal period, suggesting that identity transition may have implications for maternal health behaviours.

Our findings also reveal that beyond the insularity of the mother and baby, various external factors influenced women’s behaviour. In particular, social support was shown to be an important influence, especially from a partner. Previous research has shown that women whose partners continue to smoke or drink throughout pregnancy are significantly less likely to change their own behaviour (McLeod et al., Citation2003; Ortega-García et al., Citation2020). This is important as partners are not likely to make behavioural changes during this time (Everett et al., Citation2007), and therefore highlights the importance of engaging partners in discussions surrounding lifestyle changes during the antenatal period.

Women’s knowledge and understanding about the target health behaviour was also shown to be an influential factor. In particular, lack of understanding about health outcomes and low risk perceptions were identified as barriers to change. This is consistent with several behavioural theories which suggest that risk perceptions and outcome expectancies are a key element underpinning motivation to change (Becker, Citation1974; McBride et al., Citation2003). Women’s understanding was further hindered by confusing and conflicting messages received from health professionals and government advice, which is also evident in the findings of other studies (Stockton & Nield, Citation2020; Weeks et al., Citation2018). This is important to reflect upon, as delivering a consistent message has been shown to increase adherence to antenatal advice (Shanmugalingam et al., Citation2020), highlighting the need for dissemination of clear messages, through health professionals to service users.

The review findings highlighted factors such as social disadvantage and economic deprivation as influencing health behaviours. These findings are consistent with the results of previous quantitative studies that have shown a relationship between socio-economic status and deprivation, and rates of smoking, alcohol use, and dietary behaviour (Bodnar et al., Citation2017; de Wolff et al., Citation2019; Onah et al., Citation2016). Going forward, it will be important to consider the influence of these factors on health behaviour to ensure that any theory of change developed is appropriate and accounts for the impact of non-modifiable factors such as these.

Our findings suggest that women’s decision-making is influenced by an interplay of intrinsic and extrinsic motivations, concepts defined in Self-Determination Theory (SDT; Ryan & Deci, Citation2000). For example, theme one clearly identifies intrinsic motivations related to individual needs and autonomy. Conversely, the remaining themes provide examples of extrinsic motivations related to societal expectations, social influence, and external environments. Individuals who are intrinsically motivated often display improved performance of the target behaviour (Ryan & Deci, Citation2000). This may have implications for theory and intervention development, as addressing intrinsic motivations may therefore result in improved behavioural outcomes.

It is also of note that a number of influencing factors identified in this review acted as either barriers or facilitators to the same behaviour, for different women. For example, judgement and societal pressure was experienced by some women as a facilitator to smoking cessation, whilst for others, it acted to encourage the behaviour. Similarly, some factors encouraged both healthy and unhealthy behaviours. For example, concern about risk motivated some women to improve their dietary behaviour but drove others to reduce their physical activity levels. This highlights the importance of individual differences in human behaviour and decision-making and the value of tailoring the delivery of health promotion advice to individuals.

Importantly, the review findings suggest that factors identified as influencing behaviour change apply to all four health behaviours, to varying extents. While differences were found during the initial coding stage of the analysis, the inductive process of grouping and synthesising the data revealed similarities across the four health behaviours, at the sub-theme, and overarching theme level. This is important and may have implications for future theory development as it suggests that theoretical models may not need to be behaviour-specific if the model components address relevant influencing factors. Likewise, behaviour-specific theory may be utilised effectively in alternate contexts if the model similarly incorporates components that address the factors identified in this review.

However, it is important to consider limitations of the included studies. In particular, response bias may have had an impact on the way in which participants responded to researchers, especially given the qualitative nature of the research. As such, our findings may have been skewed by this. Furthermore, dissertations and theses were included in this review; studies conducted as part of university courses may be of a lower standard than peer-reviewed articles. This may not be reflected accurately in the quality assessment, as dissertations/theses in particular often allow for greater discussion of methodological detail, satisfying many of the CASP criteria, but may lack trustworthiness and rigor not otherwise captured by the reported information. However, including these sources provides a more complete view of the available evidence (Mahood et al., Citation2014).

Strengths and limitations

This was an extensive review that synthesises common findings from a disparate literature, highlighting the diversity of factors that may influence women’s decision-making. The review protocol was pre-registered, and the review was conducted rigorously, including grey literature and non-English language studies (Rockliffe, Citation2021). However, there are a number of potential limitations to be considered.

The inclusion/exclusion criteria for the systematic review were designed to reduce variability in the advice women may have received about the behaviours of interest (i.e., excluding women on specialist care pathways, or those advised to modify certain behaviours). However, it is likely that individual variability affected the results to some extent. For example, multiparous women sometimes altered their behaviour in subsequent pregnancies based on their previous experience. Therefore, future research should consider whether the experiences of nulliparous and multiparous women are distinct. Furthermore, it is likely that cultural differences, or differences in healthcare advice, will have varied between countries despite limiting included studies to high-income countries (Abalos et al., Citation2016; Evenson et al., Citation2013). It is important to take this into account when interpreting the findings, as these differences are likely to be an implicit factor affecting women’s behaviour.

Implications for theory and clinical practice

The factors identified in this review provide a foundation from which a pregnancy-specific theory of behaviour change, and in turn interventions, can be developed. Our findings lend support for the model constructs posited by McBride et al. (Citation2003). However, it would be beneficial to explore this in greater detail in future research, to assess the extent to which influencing factors can be mapped to the model. It may also be valuable to explore the use of alternative behaviour change theories in this context, such as the Capability-Opportunity-Motivation Behaviour model (COM-B; Michie et al., Citation2011), which has been suggested to provide a superior understanding of pregnancy as a teachable moment (Olander et al., Citation2016). Developing a clearer understanding of the efficacy of existing models to explain pregnancy as a teachable moment is an important step in the development of a pregnancy-specific theory. Further to this, it may also be advantageous to consider the role of theories such as SDT and the influence of differing types of motivation on desired behavioural outcomes (Ryan & Deci, Citation2000).

Future research may wish to further define and investigate the barriers and facilitators to behaviour change identified in this study, from which practical and clinical recommendations can be developed. However, independent of future work, the findings of this review have valuable clinical implications. In particular, highlighting the importance of taking a holistic approach to behaviour change, by considering multiple internal and external factors that may influence women’s decision-making and motivation. Furthermore, the findings emphasise the importance of delivering behavioural advice that is appropriate and consistent.

Conclusions

Women’s desire to think about their own needs, their adoption of the ‘good mother’ role, and external factors beyond the mother and baby, all appear to influence women’s decision-making about their health behaviour during pregnancy. In clinical practice, it is important to consider the myriad of internal and external factors that may affect women’s motivation to change their behaviour, and to take a holistic view of maternal health when delivering behaviour change advice. These findings provide us with an improved understanding of the underlying mechanisms influencing maternal decision-making, which future research can build upon to develop appropriate, meaningful theory specific to this context.

Author’s contributions

All authors contributed to the research idea and study design. LR – conducted literature search/screening, quality appraisal, data synthesis/interpretation, manuscript preparation. SP – supported literature search/screening, supported data synthesis/interpretation, reviewed/redrafted the manuscript. AH – supported literature search/screening, reviewed/redrafted the manuscript. DS – supported literature search/screening, supported quality appraisal, data synthesis/interpretation, reviewed/redrafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (947.7 KB)Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the help of all individuals who provided translation support, to the authors who kindly responded to requests for study information, and to the university librarians for their help developing the search strategy.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

I Pregnancy-related health behaviours are those that occur outside of pregnancy, that evidence suggests are beneficial to health if maintained or modified during the antenatal period. Pregnancy-specific behaviours are those that occur during pregnancy only, that evidence suggests are beneficial to health if initiated during this period (e.g., recommended dietary changes, recommended supplementation, etc.) (Olander et al., Citation2018).

II The CASP criteria were modified by omitting question ten and defining criterion hints according to discussions between LR and DS.

III On two occasions, two studies analysed data collected from the same participant sample. The total number of participants included therefore reflects 90 studies. All other reported characteristics reflect the total 92 studies.

IV Where women chose to continue drinking alcohol, it was often reported to be consumed in greater moderation than in pre-pregnancy, or limited to settings deemed socially acceptable, such as special occasions (e.g., birthdays, weddings), or as an accompaniment to a meal.

References

- Abalos, E., Chamillard, M., Diaz, V., Tuncalp, Ö., & Gülmezoglu, A. (2016). Antenatal care for healthy pregnant women: A mapping of interventions from existing guidelines to inform the development of new WHO guidance on antenatal care. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 123(4), 519–528. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.13820

- Barnett-Page, E., & Thomas, J. (2009). Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: A critical review. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 9(1), 59. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-9-59

- Bartholomew, L. K., & Mullen, P. D. (2011). Five roles for using theory and evidence in the design and testing of behavior change interventions. Journal of Public Health Dentistry, 71(s1), S20–S33. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-7325.2011.00223.x

- Becker, M. H. (1974). The health belief model and sick role behavior. Health Education Monographs, 2(4), 409–419. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/109019817400200407

- Bodnar, L. M., Simhan, H. N., Parker, C. B., Meier, H., Mercer, B. M., Grobman, W. A., Haas, D. M., Wing, D. A., Hoffman, M. K., Parry, S., Silver, R. M., Saade, G. R., Wapner, R., Iams, J. D., Wadhwa, P. D., Elovitz, M., Peaceman, A. M., Esplin, S., Barnes, S., & Reddy, U. M. (2017). Racial or ethnic and socioeconomic inequalities in adherence to national dietary guidance in a large cohort of US pregnant women. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 117(6), 867–877.e3. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2017.01.016

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Novel insights into patients’ life-worlds: The value of qualitative research. The Lancet Psychiatry, 6(9), 720–721. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30296-2

- Brown, M. J., Sinclair, M., Liddle, D., Hill, A. J., Madden, E., & Stockdale, J. (2012). A systematic review investigating healthy lifestyle interventions incorporating goal setting strategies for preventing excess gestational weight gain. PLoS ONE, 7(7), e39503. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0039503

- Carroll, C., Booth, A., & Lloyd-Jones, M. (2012). Should we exclude inadequately reported studies from qualitative systematic reviews? An evaluation of sensitivity analyses in two case study reviews. Qualitative Health Research, 22(10), 1425–1434. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732312452937

- Clarivate. (2016). EndNote X8.0.1. https://endnote.com/.

- Coleman, T., Cooper, S., Thornton, J. G., Grainge, M. J., Watts, K., Britton, J., & Lewis, S. (2012). A randomized trial of nicotine-replacement therapy patches in pregnancy. New England Journal of Medicine, 366(9), 808–818. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1109582

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. (2018). CASP qualitative checklist. Retrieved December, 2020, from https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018.pdf.

- Currie, S., Sinclair, M., Murphy, M. H., Madden, E., Dunwoody, L., & Liddle, D. (2013). Reducing the decline in physical activity during pregnancy: A systematic review of behaviour change interventions. PLOS ONE, 8(6), e66385. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0066385

- de Wolff, M. G., Backhausen, M. G., Iversen, M. L., Bendix, J. M., Rom, A. L., & Hegaard, H. K. (2019). Prevalence and predictors of maternal smoking prior to and during pregnancy in a regional Danish population: A cross-sectional study. Reproductive Health, 16(1), 82. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-019-0740-7

- Dixon-Woods, M., Sutton, A., Shaw, R., Miller, T., Smith, J., Young, B., Bonas, S., Booth, A., & Jones, D. (2007). Appraising qualitative research for inclusion in systematic reviews: A quantitative and qualitative comparison of three methods. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 12(1), 42–47. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1258/135581907779497486

- Dodd, J. M., Crowther, C. A., & Robinson, J. S. (2008). Dietary and lifestyle interventions to limit weight gain during pregnancy for obese or overweight women: A systematic review. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 87(7), 702–706. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00016340802061111

- Dodd, J. M., Turnbull, D., McPhee, A. J., Deussen, A. R., Grivell, R. M., Yelland, L. N., Crowther, C. A., Wittert, G., Owens, J. A., & Robinson, J. S. (2014). Antenatal lifestyle advice for women who are overweight or obese: LIMIT randomised trial. BMJ, 348(feb10 3), g1285. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g1285

- Edlow, A. G. (2017). Maternal obesity and neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders in offspring. Prenatal Diagnosis, 37(1), 95–110. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/pd.4932

- Escañuela Sánchez, T., Meaney, S., & O’Donoghue, K. (2019). Modifiable risk factors for stillbirth: A literature review. Midwifery, 79, 102539. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2019.102539

- Evans, D., & Pearson, A. (2001). Systematic reviews of qualitative research. Clinical Effectiveness in Nursing, 5(3), 111–119. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1054/cein.2001.0219

- Evenson, K. R., Barakat, R., Brown, W. J., Dargent-Molina, P., Haruna, M., Mikkelsen, E. M., Mottola, M. F., Owe, K. M., Rousham, E. K., & Yeo, S. (2013). Guidelines for physical activity during pregnancy: Comparisons from around the world. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 8(2), 102–121. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1559827613498204

- Everett, K. D., Bullock, L., Longo, D. R., Gage, J., & Madsen, R. (2007). Men’s tobacco and alcohol use during and after pregnancy. American Journal of Men’s Health, 1(4), 317–325. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988307299477

- Flannery, C., Fredrix, M., Olander, E. K., McAuliffe, F. M., Byrne, M., & Kearney, P. M. (2019). Effectiveness of physical activity interventions for overweight and obesity during pregnancy: A systematic review of the content of behaviour change interventions. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrtrition and Physical Acticity, 16(1), 97. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-019-0859-5

- Flemming, K., & Noyes, J. (2021). Qualitative evidence synthesis: Where are we at? International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 20, 1–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406921993276

- Goodwin, S., & Huppatz, K. (2010). The good mother: Contemporary motherhoods in Australia. Sydney University Press.

- Gutvirtz, G., Wainstock, T., Landau, D., & Sheiner, E. (2019). Maternal smoking during pregnancy and long-term neurological morbidity of the offspring. Addictive Behaviors, 88, 86–91. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.08.013

- Hayes, L., McParlin, C., Azevedo, L. B., Jones, D., Newham, J., Olajide, J., McCleman, L., & Heslehurst, N. (2021). The Effectiveness of smoking cessation, alcohol reduction, diet and physical activity interventions in improving maternal and infant health outcomes: A systematic review of meta-analyses. Nutrients, 13(3), 1036. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13031036

- Heslehurst, N., Vieira, R., Akhter, Z., Bailey, H., Slack, E., Ngongalah, L., Pemu, A., & Rankin, J. (2019). The association between maternal body mass index and child obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS Medicine, 16(6), e1002817. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002817

- Hodgkinson, E. L., Smith, D. M., & Wittkowski, A. (2014). Women’s experiences of their pregnancy and postpartum body image: A systematic review and meta-synthesis. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 14(1), 330. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-14-330

- Johnston, D. D., & Swanson, D. H. (2003). Invisible mothers: A content analysis of motherhood ideologies and myths in magazines. Sex Roles, 49(1), 21–33. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023905518500

- Kennelly, M. A., Ainscough, K., Lindsay, K. L., O’Sullivan, E., Gibney, E. R., McCarthy, M., Segurado, R., DeVito, G., Maguire, O., Smith, T., Hatunic, M., & McAuliffe, F. M. (2018). Pregnancy exercise and nutrition with smartphone application support: A randomized controlled trial. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 131(5), 818–826. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000002582

- Lindqvist, M., Lindkvist, M., Eurenius, E., Persson, M., & Mogren, I. (2017). Change of lifestyle habits – Motivation and ability reported by pregnant women in northern Sweden. Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare, 13, 83–90. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.srhc.2017.07.001

- Liu, B., Xu, G., Sun, Y., Qiu, X., Ryckman, K. K., Yu, Y., Snetselaar, L. G., & Bao, W. (2020). Maternal cigarette smoking before and during pregnancy and the risk of preterm birth: A dose–response analysis of 25 million mother–infant pairs. PLOS Medicine, 17(8), e1003158. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003158

- Long, H. A., French, D. P., & Brooks, J. M. (2020). Optimising the value of the critical appraisal skills programme (CASP) tool for quality appraisal in qualitative evidence synthesis. Research Methods in Medicine & Health Sciences, 1(1), 31–42. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2632084320947559

- Mahood, Q., Van Eerd, D., & Irvin, E. (2014). Searching for grey literature for systematic reviews: Challenges and benefits. Research Synthesis Methods, 5(3), 221–234. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1106

- Marshall, J. L., Godfrey, M., & Renfrew, M. J. (2007). Being a ‘good mother’: Managing breastfeeding and merging identities. Social Science & Medicine, 65(10), 2147–2159. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.06.015

- McBride, C. M., Emmons, K. M., & Lipkus, I. M. (2003). Understanding the potential of teachable moments: The case of smoking cessation. Health Education Research, 18(2), 156–170. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/her/18.2.156

- McLeod, D., Pullon, S., & Cookson, T. (2003). Factors that influence changes in smoking behaviour during pregnancy. New Zealand Medical Journal, 116(1173), U418.

- Michie, S., Johnston, M., Francis, J., Hardeman, W., & Eccles, M. (2008). From theory to intervention: Mapping theoretically derived behavioural determinants to behaviour change techniques. Applied Psychology, 57(4), 660–680. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00341.x

- Michie, S., van Stralen, M. M., & West, R. (2011). The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Science, 6(1), 42. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-6-42

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 62(10), 1006–1012. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2008). Antenatal care for uncomplicated pregnancies [NICE Guideline No. CG62]. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg62.

- O’Brien, O. A., Lindsay, K. L., McCarthy, M., McGloin, A. F., Kennelly, M., Scully, H. A., & McAuliffe, F. M. (2017). Influences on the food choices and physical activity behaviours of overweight and obese pregnant women: A qualitative study. Midwifery, 47, 28–35. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2017.02.003

- Olander, E. K., Darwin, Z. J., Atkinson, L., Smith, D. M., & Gardner, B. (2016). Beyond the ‘teachable moment’ – A conceptual analysis of women’s perinatal behaviour change. Women and Birth, 29(3), e67–e71. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2015.11.005

- Olander, E. K., Smith, D. M., & Darwin, Z. (2018). Health behaviour and pregnancy: A time for change. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 36(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2018.1408965

- Onah, M. N., Field, S., van Heyningen, T., & Honikman, S. (2016). Predictors of alcohol and other drug use among pregnant women in a peri-urban South African setting. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 10, 38. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-016-0070-x

- Ortega-García, J. A., López-Hernández, F. A., Azurmendi Funes, M. L., Sánchez Sauco, M. F., & Ramis, R. (2020). My partner and my neighbourhood: The built environment and social networks’ impact on alcohol consumption during early pregnancy. Health & Place, 61, 102239. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.102239

- Pedersen, S. (2016). The good, the bad and the ‘good enough’ mother on the UK parenting forum Mumsnet. Women’s Studies International Forum, 59, 32–38. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2016.09.004

- Phelan, S. (2010). Pregnancy: A “teachable moment” for weight control and obesity prevention. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 202(2), 135.e1–135.e8. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2009.06.008

- Poston, L., Bell, R., Croker, H., Flynn, A. C., Godfrey, K. M., Goff, L., Hayes, L., Khazaezadeh, N., Nelson, S. M., Oteng-Ntim, E., Pasupathy, D., Patel, N., Robson, S. C., Sandall, J., Sanders, T. A. B., Sattar, N., Seed, P. T., Wardle, J., Whitworth, M. K., & Briley, A. L. (2015). Effect of a behavioural intervention in obese pregnant women (the UPBEAT study): A multicentre, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, 3(10), 767–777. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00227-2

- QSR International Pty Ltd. (2018). NVivo (Version 12). https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home.

- Rockliffe, L. (2021). Including non-English language articles in systematic reviews: A reflection on processes for identifying low-cost sources of translation support. Manuscript submitted for publication.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

- Scarborough, P., Bhatnagar, P., Wickramasinghe, K. K., Allender, S., Foster, C., & Rayner, M. (2011). The economic burden of ill health due to diet, physical inactivity, smoking, alcohol and obesity in the UK: An update to 2006–07 NHS costs. Journal of Public Health, 33(4), 527–535. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdr033

- Shanmugalingam, R., Mengesha, Z., Notaras, S., Liamputtong, P., Fulcher, I., Lee, G., Kumar, R., Hennessy, A., & Makris, A. (2020). Factors that influence adherence to aspirin therapy in the prevention of preeclampsia amongst high-risk pregnant women: A mixed method analysis. PLOS ONE, 15(2), e0229622. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0229622

- Stacy, S. L., Buchanich, J. M., Ma, Z.-q., Mair, C., Robertson, L., Sharma, R. K., Talbott, E. O., & Yuan, J.-M. (2019). Maternal obesity, birth size, and risk of childhood cancer development. American Journal of Epidemiology, 188(8), 1503–1511. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwz118

- Stockton, J., & Nield, L. (2020). An antenatal wish list: A qualitative systematic review and thematic synthesis of UK dietary advice for weight management and food borne illness. Midwifery, 82, 102624. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2019.102624

- Sundermann, A. C., Zhao, S., Young, C. L., Lam, L., Jones, S. H., Velez Edwards, D. R., & Hartmann, K. E. (2019). Alcohol use in pregnancy and miscarriage: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 43(8), 1606–1616. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.14124

- Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8(1), 45. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

- Tong, A., Flemming, K., McInnes, E., Oliver, S., & Craig, J. (2012). Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 12(1), 181. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-12-181

- Weeks, A., Liu, R. H., Ferraro, Z. M., Deonandan, R., & Adamo, K. B. (2018). Inconsistent weight communication among prenatal healthcare providers and patients: A narrative review. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey, 73(8), 486–499. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/ogx.0000000000000588

- The World Bank. (2019). World Bank country and lending groups: Country classification. Retrieved March, 2019, from https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519.

- World Health Organisation. (2020). Noncommunicable diseases: Progress monitor 2020. World Health Organisation. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/330805

- Yang, Z., Phung, H., Freebairn, L., Sexton, R., Raulli, A., & Kelly, P. (2019). Contribution of maternal overweight and obesity to the occurrence of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 59(3), 367–374. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/ajo.12866

- Yelverton, C. A., Geraghty, A. A., O’Brien, E. C., Killeen, S. L., Horan, M. K., Donnelly, J. M., Larkin, E., Mehegan, J., & McAuliffe, F. M. (2020). Breastfeeding and maternal eating behaviours are associated with child eating behaviours: Findings from the ROLO kids study. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 75(4), 670–679. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-020-00764-7

- Zarychta, K., Kulis, E., Gan, Y., Chan, C. K. Y., Horodyska, K., & Luszczynska, A. (2019). Why are you eating, mom? Maternal emotional, restrained, and external eating explaining children’s eating styles. Appetite, 141, 104335. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2019.104335

- Zhang, S., Wang, L., Yang, T., Chen, L., Zhao, L., Wang, T., Chen, L., Zheng, Z., & Qin, J. (2020). Parental alcohol consumption and the risk of congenital heart diseases in offspring: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology, 27(4), 410–421. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487319874530