ABSTRACT

The trend of incorporating culture and heritage into various aspects of tourism, such as film-related tourism, is gaining momentum. In addition to the film-related attractions, film-related tourism can encourage tourists’ engagement with cultural heritage tourism and consumption of heritage products at the destination. Examining the case of Hengdian World Studios (China), the world’s largest outdoor film studio and film shooting base, this paper discusses how cultural heritage tourism is induced at a film-related tourism destination as well as how the tourism destination represents authenticity and how tourists perceive such representations. Hengdian World Studios simulates several real heritage sites in different areas of China for screen media productions as well as for tourist consumption. This paper examines the concepts of ‘staged authenticity’ (MacCannell [1973]. Staged authenticity: Arrangements of social space in tourist settings. American Journal of Sociology, 79(3), 589–603. https://doi.org/10.1086/225585) and ‘existential authenticity’ (Wang [1999]. Rethinking authenticity in tourism experience. Annals of Tourism Research, 26(2), 349–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0160-7383(98)00103-0) in the context of tourism studies to understand cultural heritage tourism at film-related tourism sites. The discussion is based on research undertaken at Hengdian World Studios between 2018 and 2023 drawing on ethnographic methods and online interviews with 50 tourists. This paper contributes to the understanding of authenticity issues in tourism studies from different perspectives and the interconnections between film-related tourism and cultural heritage tourism.

Introduction

The debate about authenticity issues in tourism research has never been resolved, and it is also one of the oldest and most-discussed concepts in tourism research (Rickly, Citation2022). Although it seems unavoidable and important in practice, its theoretical status remains unclear (Moore et al., Citation2021). To a large degree, this is because authenticity itself is conceived as a negotiable concept (Canavan & McCamley, Citation2021; Cohen, Citation1988; Halewood & Hannam, Citation2001; Wang, Citation1999). Even though previous discussions of authenticity focused on the topic of what is real and what is fake (Andriotis, Citation2009), the meanings of ‘authenticity’ and ‘inauthenticity’ are interpretative, intertwined, contextual, personal, fluid and incomplete (Canavan & McCamley, Citation2021). Authenticity is not a matter of black and white (Wang, Citation1999). According to Steiner and Reisinger (Citation2006, p. 299), ‘authenticity’ is always applied in two distinct senses: ‘authenticity as genuineness or realness of artefacts or events’ and ‘authenticity as a human attribute signifying being one’s true self or being true to one’s essential nature.’ In tourism, authenticity can be conceptualised as either an object-related or an experience-related phenomenon (Lu et al., Citation2015; Moore et al., Citation2021; Wang, Citation1999). Based on these two senses, a range of classifications and sub-forms were introduced and applied in previous tourism literature, such as objective authenticity, constructive authenticity, performative authenticity, postmodern authenticity, staged authenticity, and existential authenticity (Rickly, Citation2022). In this paper, the concepts of ‘staged authenticity’ and ‘existential authenticity’ alongside the concept of ‘objective authenticity’ will be applied in the discussions with a focus on the authenticity of tourism objects and the authenticity of tourists’ experiences of cultural heritage tourism at film-related tourism sites.

After reviewing 458 research articles on authenticity in tourism published between 1979 and 2020, Rickly (Citation2022) found that ‘cultural heritage’ was a prominent meta-theme and dominant topic in the literature. Authenticity has been considered as the central contribution of a destination in the context of heritage tourism (Boyd, Citation2002; Chhabra et al., Citation2003; Lu et al., Citation2015). Lovell (Citation2019) argues that objective authenticity is often employed by heritage tourists because of its focus on the auratic, cultic qualities of remoteness, value and rarity. However, a number of researchers suggest that tourists form their perceptions of authenticity based on the subjective evaluation of their experiences and activities (Lu et al., Citation2015). Additionally, in tourism research, MacCannell (Citation1973) suggests that touristic space can be referred to as a ‘stage set,’ a ‘tourist setting,’ or simply a ‘set,’ depending on how purposefully worked up for tourists the display is. The ‘staged authenticity’ approach can be used to re-create and re-enact heritage traditions, as experiencing authenticity is more about feeling authentic than having a ‘real’ and ‘objective’ experience (Chhabra et al., Citation2003). Therefore, previous studies utilised different perspectives and directions to look at the authenticity issues of cultural heritage tourism.

Although staged authenticity and existential authenticity might initially seem like separate research areas, there are actually a significant co-relation between these two sub-types of authenticity. In our case study, the co-relations are reflected in the fact that the film studios strive to stage the authenticity of their cultural heritage tourism objects in order to provide tourists with better travel experiences. Indeed, for a group of tourists, this to some extent prompts them to seek out an existentially authentic encounter. However, it is important to note that tourists’ judgements on authenticity are not solely determined by the staged performances at the destination. Tourists’ subjectivity, emotions, knowledge, cultural familiarity, and something else, all play important roles in shaping their perceptions of authenticity.

This paper will first review the key concepts and terms in relation to film-related tourism, cultural heritage tourism, staged authenticity, and existential authenticity. Then, it will introduce the research methods applied in this study and the research setting. Following this, the paper will show the discussions and findings of this study, which will be divided into two sections, respectively focusing on (a) how the destination represents the authenticity of its cultural heritage tourism and tourism objects and (b) how the tourists perceive and understand the authenticity in their journeys. The concepts of staged authenticity and existential authenticity in tourism studies will be discussed in these two sections. Finally, based on the findings of these two sections, this paper will discuss the connections between staged authenticity of tourism objects and existential authenticity of tourists’ experiences. It will also demonstrate the characteristics of cultural heritage tourism at film-related tourism sites using the case of Hengdian World Studios. This study makes important contributions to the literature on authenticity in tourism studies through discussing tourists’ authentic experiences at one tourism site with two types of tourism. It not only examines the theoretical framework of authenticity but also includes an empirical investigation into how a tourism destination presents the authenticity of its heritage touristic objects and how tourists perceive authenticity in their touristic experiences.

Literature review

Film-related tourism

Over the past three decades, there has been a growing interest in researching film-related tourism (Oviedo-García et al., Citation2016). By the early 2000s, the concept of film-related tourism has gained momentum in tourism research, with most of the related knowledge obtained from case studies (Connell, Citation2012). Film-related tourism is a growing global cultural phenomenon, driven by the growth of the entertainment industry and global travel (Yen & Croy, Citation2016). Many definitions were introduced and applied to describe this cultural phenomenon in the research area of film-related tourism. For the purpose of this article, the term ‘film-related tourism’ will be applied because it not only highlights the power of film in motivating people’s journeys to film-related touristic sites but also includes the influence of other (film-related) screen media. As suggested by Beeton (Citation2011, Citation2015), the term ‘film-related tourism’ is appropriate for use in a situation where the on-site film-related elements, such as stories, services, activities, and facilities, play specific roles in stimulating film tourists’ visits to a destination. Thus, the definition of film-related tourism in this paper is stated as a cultural phenomenon where people visit a site as a result of it having been featured in a moving image and/or involving and representing film-related elements on-site.

Co-existence of film-related tourism and cultural heritage tourism

The integration of culture and heritage into different aspects of tourism is becoming increasingly prevalent (Agarwal & Shaw, Citation2017), as with the example of film-related tourism, reflecting the multiple ways tourists consume tourism products (Richards, Citation1996). Agarwal and Shaw (Citation2017) utilise the examples of The Last Emperor (Bernardo Bertolucci, 1987) film tour in Beijing’s Forbidden City and Hero (Yimou Zhang, 2003) film tour in Jiuzhaigou National Park to demonstrate that tourism generated by period films and television productions is influenced by the interplay between heritage elements and the significance of filming locations. This demonstrates the interrelation between film-related tourism products and cultural heritage tourism products and shows the potential for film-related tourism and cultural heritage tourism to coexist at a single destination.

Cultural heritage tourism focuses on the cultural heritage of a particular destination, with tourists being primarily motivated to visit based on their own understanding of the location’s heritage features (Agarwal & Shaw, Citation2017; IGI Global, Citationn.d.; Poria et al., Citation2003). According to Kaminski et al. (Citation2013, p. 4), in cultural heritage tourism, ‘the need to present touristic offerings that include cultural experiences and heritage has become widely recognised.’ Tourists who engage in cultural heritage tourism are often motivated to gain knowledge and appreciation for local art, architecture, and traditions (Lu et al., Citation2015).

Cultural heritage is understood as a process of meaning and memory making and remaking rather than an object or product (Smith, Citation2006). What people engage with in heritage tourism are their emotions, memories, cultural knowledge, and experiences, which can be symbolised by heritage sites or represented through cultural practices (Smith, Citation2006). In this context, the meaning and impact of heritage are more important than the type of heritage in understanding history and culture and collecting individual or social memories. Smith’s viewpoint (Citation2006) is also consistent with the characteristics of cultural heritage tourism in China. Scholars in Chinese tourism studies emphasise the feasibility and practicality of representing Chinese history and culture through simulating and rebuilding real heritage sites, given the current situation of conservation and inheritance of heritage buildings in China (Piazzoni, Citation2018; Su, Citation2008). In the Chinese context, a copy can be as valuable as its original. Chinese people have not rejected the appearance of copies nor have they denied the significance of copies in the presentation of Chinese culture and history. This is because in China, although a copy is considered less valuable than its initial model, if a replica manages to capture the essential qualities of the source material, it can become equally valued and appreciated (Piazzoni, Citation2018). Such a context is also in relation to how people understand authenticity.

Staged authenticity and existential authenticity in tourism studies

As discussed previously, authenticity can be classified into different types, such as ‘object-related’ and ‘experience-related’ authenticity (Lu et al., Citation2015; Moore et al., Citation2021; Wang, Citation1999). Staged authenticity, which refers to how local touristic elements (objects, people, stories, etc.) are staged and performed to convince tourists of the local tourism products and environments, is more like a type of ‘object-related’ authenticity associated with the performative perspective in tourism studies. Furthermore, authenticity can be associated with objective, subjective, and performative perspectives in conceptualising the term (Zhu, Citation2012). What tourists see and experience in a touristic space is often staged (MacCannell, Citation1973), and in this regard, tourists searching for authenticity in their travel in some situations are consumers of staged authenticity. This type of authenticity involves the staging of local tourism objects and culture to create an impression of authenticity for visitors (Chhabra et al., Citation2003; Gotham, Citation2018; Lovell & Bull, Citation2019; MacCannell, Citation1973). In tourism studies, in contrast to ‘objective authenticity,’ which refers to the historically correct and meaningful cultural displays (MacCannell, Citation1973; Rittichainuwat et al., Citation2017; Steiner & Reisinger, Citation2006), staged authenticity is a kind of ‘strained truthfulness,’ which is similar in most of its particulars to a little lie, and touristic experience in this regard is based on inauthenticity (MacCannell, Citation1973). As a kind of interdisciplinary cultural phenomenon, film tourism prompts a multi-layered exploration among tourists regarding the true meaning of an authentic experience (or related terminologies used interchangeably) when they discuss their encounters (Buchmann et al., Citation2010). As Macionis (Citation2004) suggests, searching for authenticity during film journeys is one of the core travel motivations of film tourists to visit a tourist destination. Tourists are the consumers of touristic staged authenticity at a destination, in which touristic objects, settings, facilities, and environment are well-designed and staged for tourism purposes. In film-related tourism studies, themes and topics in relation to authenticity and in-authenticity are also well-discussed and examined (e.g. Beeton, Citation2016; Bolan et al., Citation2011; Buchmann et al., Citation2010). Buchmann et al. (Citation2010) suggest that films can be understood inherently as representations, simulations and contrivances, and the realm of tourist activity known as film-related tourism serves as a robust and empirical ‘field test’ for existential authenticity. It can often have nothing to do with the issue of whether toured objects are real but refers to an existential state of being activated by certain tourist activities (Wang, Citation1999). Namely, tourists have their own judgments on authenticity of their travel experiences, even though the place is a ‘stage set.’ Previous discussions and definitions of authenticity and the sub-types of authenticity have shown the rationale that a group of tourists would like to experience cultural heritage tourism at film-related tourism sites. Our study further demonstrates that only if tourists believe that the so-called cultural heritage they see at film-related tourism sites are authentic, then their cultural heritage experiences are existentially authentic.

The concept of staged authenticity does not imply that everything at a tourist site is unreal or unreliable, but for a group of tourists, their experiences and feelings are real and existentially authentic. Authentic experiences are just as possible in the presence of reproductions as they are in the presence of originals (Moore et al., Citation2021). In some cases, what is staged can even be more authentic than the original (Canavan & McCamley, Citation2021; Chhabra et al., Citation2003; Daugstad & Kirchengast, Citation2013). Groups of tourists enjoy experiencing hyper-real touristic sites where there is no single, authentic experience but instead multiple elements that feel like a game (Baudrillard, Citation1983; Eco, Citation1983; Lovell & Bull, Citation2019; Urry, Citation1990). In film-related tourism studies, cases of film studio theme park tourism reflect that tourists are more interested in exciting fantasy than mundane reality, and they think simulacra and commodified experiences are more significant than authenticity (Beeton, Citation2016). This suggests that, from the perspective of tourists, simulations could be better than the real things, depending on how tourists perceive them and make personal judgements on whether their experiences are (existentially) authentic or not. Existential authenticity, understood in the activity-based way, seems particularly well-suited to understanding evolving tourist experiences, and as it is argued that this authenticity might hold particular significance in elucidating film-related tourism experience, and conversely, the film-related tourism experience could provide valuable insights for a deeper comprehension of existential authenticity (Buchmann et al., Citation2010).

Not all tourists fail to realise that what they see at a destination might be a staged performance. Some tourists are aware of the staged authenticity at a tourist site and still manage to have an existential authenticity through visiting the sites and engaging in tourist activities, which refers to a state of being in which people are true to themselves (Moore et al., Citation2021; Steiner & Reisinger, Citation2006; Wang, Citation1999). This is to a large degree because ‘authenticity’ is something subjectively assigned to a destination and its sites by individuals or groups, and objective authenticity no longer has the monopoly on authentic place (Reijnders, Citation2011). Unlike object-related authenticity, existential authenticity is not necessarily concerned with the authenticity of the objective touristic elements but is rather subjectively established based on individuals’ travel emotions, beliefs, experiences, and memories (Knudsen et al., Citation2016). Therefore, a tourist’s authentic experience may lie in the very inauthenticity of a tourist attraction (Brown, Citation1996).

The different types of authenticity – objective authenticity, staged authenticity, and existential authenticity – co-exist and interact with each other (Canavan & McCamley, Citation2021; Kolar & Zabkar, Citation2010). While some tourists may acknowledge that the touristic elements are not objectively authentic, they still engage in the activities as if they were authentic or hold the potential for their own authenticity (Vidon et al., Citation2018). This highlights the importance of their subjective feelings and thoughts about authenticity in their journeys over objective truths and destinations’ representations of authenticity. Staged authenticity and existential authenticity, in tourism studies, respectively focus on the ‘reality’ of a tourism destination from the perspective of how the destinations represent it and how tourists perceive it. This could explain why a group of tourists had authentic experiences at staged cultural heritage sites, such as the simulacras and copies of heritage sites in film studios, even though they have clearly known that the sites are not objectively real.

Methods and research setting

Methods

The data and information relevant to the paper were gathered through ethnographic methods and online interviews. Some of the data discussed in the paper were collected by the authors, during the ethnographic visits to Hengdian World Studios between 2018 and 2023, in both high and low tourist seasons. This data can provide insights into how the film studios stage and present their cultural heritage tourist attractions and how tourists perceive the representation of staged authenticity.

Other data presented in this paper were collected from online interviews carried out by the authors with 50 tourists who have visited Hengdian World Studios previously. The online interviews were conducted via social media, including WeChat and Weibo from 12th to 15th April 2020 and 11th to 15th November 2023. Participants of the online interviews are the online users of these two Chinese online platforms, who replied to the authors’ request post – ‘share your touristic experience in Hengdian, if you have been there before’ on WeChat, or who posted certain travel notes about their journeys with some key words of ‘Hengdian’ and ‘Hengdian World Studios’ on Weibo. The interviews were divided into two sections focusing on the participants’ film-related tourism experiences and cultural heritage tourism experiences. This paper will only present the section on cultural heritage tourism experiences and authenticity issues. All participants were given pseudonyms, i.e. Participants 1, 2, 3 … 50, in order to comply with the policy of anonymity. As the interviews were conducted in Chinese, they were translated into English as transcripts. Interview data in this thesis were analysed based on the original contents (Chinese) and transcripts. Content analysis of interview data was undertaken in an inductive thematic manner. When discussing certain research topics and themes, the relevant interview contents were selected from the transcripts and critically interpreted in the text to support the discussions and viewpoints put forward in this paper.

Research setting

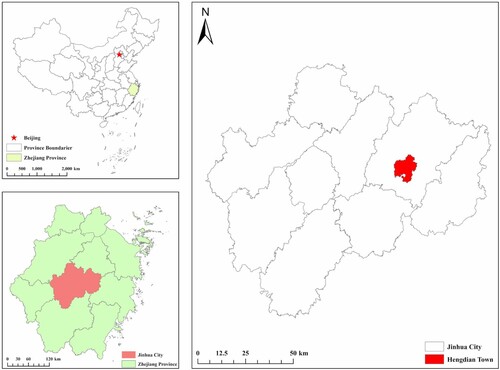

Hengdian World Studios, located in Hengdian Town, Jinhua City, Zhejiang Province, China (), was established in 1996, and it is the world’s largest outdoor shooting base and film studio theme park. By 2023, Hengdian World Studios had grown to around 130 indoor film studios and 14 outdoor film shooting bases and film-themed tourism attractions. The outdoor film studios at Hengdian World Studios have been meticulously designed to replicate the landscapes, streetscapes, and imperial and folk buildings of various Chinese dynasties spanning hundreds of years of history. They also recreate real heritage sites from across China, some of which are now derelict or no longer exist. Each outdoor studio is thematically based on the cultural characteristics and architectural style of a particular Chinese dynasty, ranging from 221 B.C. to 1912 C.E., or a specific early-modern Chinese city from the 1910s to 1940s. These film studios can serve as the ideal locations for diverse media productions and crews to shoot screen media works with different historical backgrounds and storylines. By the end of 2020, over 3200 screen media productions and crews had completed their works at Hengdian World Studios. Furthermore, in 2010, Hengdian World Studios was classified as one of the most popular tourism attractions in China by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism (formerly China National Tourism Administration) (Hengdian World Studios, Citationn.d.). Between 1996 and 2020, the total number of tourists visiting the destination reached nearly 200 million (Hengdian Group, Citation2020). As a film studio and film-related tourism site, Hengdian World Studios, with its simulation of real historic sites and cultural heritage settings for filming screen media works, also encourages tourists to consume cultural heritage tourism.

Discussion and findings

Staged authenticity of the cultural heritage elements at Hengdian World Studios

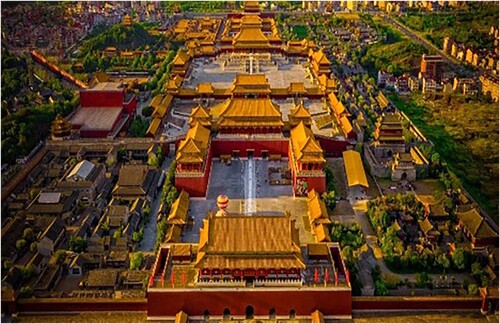

Based on the authors’ participant observation during the ethnographic visits to Hengdian World Studios, the data shows that Hengdian World Studios utilises four ways to stage the authenticity of its cultural heritage objects and environment for film-making and/or tourism purposes. One of the ways is to re-produce and re-build the high-quality simulacra or simulations of real cultural heritage sites. For example, Hengdian World Studios has built a 1:1 scale of the Forbidden City and given it the name the ‘Palace of Ming and Qing Dynasties’ film studio (Hengdian World Studios, Citationn.d.). Tourists at Hengdian World Studios are provided with a similar travel environment to that in real existing Chinese historic and cultural heritage sites. Unlike real heritage sites, the reproductions do not require the same level of protection and preservation, making them more accessible and approachable for visitors. During the ethnographic visits to Hengdian World Studios, the authors visited both the outside environment and inside settings and compared the copies to Chinese real heritage sites such as the Forbidden City ( and ). Thus, Hengdian World Studios stages the authenticity of its cultural heritage objects by completely ‘copying’ and reproducing the real heritage sites to a high degree, thus performing and staging the objects (simulations) as the real.

Figure 2. The ‘Palace of Ming and Qing Dynasties’ film studio. Source: Hengdian World Studios (Citationn.d.).

Figure 3. The Forbidden City in Beijing. Source: China Highlight (Citation2021).

Another strategy Hengdian World Studios applies to stage the authenticity is to convince tourists that their cultural heritage tourism experiences at Hengdian World Studios could be more real than the original. Based on the authors’ observation during the ethnographic visits, some tourists physically ‘interacted’ with the simulated cultural heritage settings by touching the settings, furniture and decoration, for instance, sitting at the imperial chair when taking photos (). Such a way to stage the authenticity of its cultural heritage elements can evoke emotions related to Chinese tradition, culture, history, and heritage among tourists visiting Hengdian World Studios (Meng & Tung, Citation2016). Moreover, the case of Hengdian World Studios’ cultural heritage settings, architectures, and streetscapes also supports the viewpoint that the staged objects could be more authentic than the original objects (Canavan & McCamley, Citation2021; Chhabra et al., Citation2003; Daugstad & Kirchengast, Citation2013). The main reason for this is that Hengdian World Studios is much more accessible to tourists than real heritage and historic sites like the Forbidden City. Additionally, tourists can have a more engaging and immersive experience at Hengdian World Studios, as they are permitted to physically interact with the simulated cultural heritage objects. This allows Hengdian World Studios to offer a direct engagement with representations of Chinese heritage and traditional culture. Therefore, even if some tourists have lived in areas with historical relics or visited real heritage sites before, they may still be impressed by the replicas and reproductions at Hengdian World Studios (Meng & Tung, Citation2016). Some tourists in the so-called postmodern era think simulacra and commodification are more important than authenticity (Beeton, Citation2016), and this situation provides the market for simulated and staged heritage and historic sites in the tourism industries.

Figure 4. A tourist sitting in the simulated imperial chair to take photos in ‘The Palace of Emperor Qin’ film studio at Hengdian World Studios. Source: Photo by the authors, 2020.

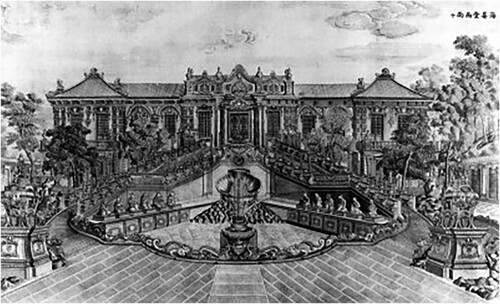

Apart from reproducing existing Chinese cultural heritage objects, Hengdian World Studios also rebuilt and reconstructed the historic sites, districts and buildings that had suffered damage or had completely vanished for both filmmaking and tourism purposes. One of its notable sites is the ‘New Yuanmingyuan’ film studio, which replicates the ‘Yuanming Yuan’ heritage site in Beijing that was destroyed in the Second Opium War around the 1840s. This film studio was constructed from 2012 to 2017 for filmmaking and as a tourist site to represent Chinese culture, heritage, and history (Zeng & Wu, Citation2019). It was possible to see the level of accuracy in the reproduction by comparing it with images taken before the actual site was destroyed. During the ethnographic visits, the authors visited the ‘New Yuanmingyuan’ film studio and found that the replicas are highly accurate compared to historical pictures of the original site before its destruction ( and ).

Figure 5. A touristic area in ‘New Yuanmingyuan’ film studio in Hengdian World Studios. Source: Captured by the authors, 2019.

Figure 6. An ancient painting shows the one area in the ‘Yuan Mingyuan’ (Beijing, China), which was destroyed in the Second Opium War around the 1840s. Source: China Reading Weekly (Citation2020).

Hengdian World Studios’ reproductions and reconstructions not only make the historic sites come to life but also provide an educational and informative experience to tourists. Visiting Hengdian World Studios enables them to learn about the history and culture of the sites in an interactive and memorable way. The reproductions and replicas become unique physical, tangible, and interactive reference sources and objects of these vanished and destroyed cultural heritage and historic sites and districts. These simulated cultural products may be recognised as ‘the authentic’ with time and take on a new significance for their producers (the studios) (Cohen, Citation1988), because authenticity in tourism is negotiable (Canavan & McCamley, Citation2021; Cohen, Citation1988; Halewood & Hannam, Citation2001; Wang, Citation1999) and as fantasy remains malleable (Knudsen et al., Citation2016).

Hengdian World Studios offers costume rental services, and the studio staff dress up in different Chinese cultural and traditional costumes to highlight the themes of the touristic spaces (). In addition, the authors observed that a group of tourists made up and dressed in film characters’ costumes with distinct Chinese traditional cultural elements for taking photos with the cultural heritage settings in one frame. Through designing the additional cultural tourist products, tourists could be immersed in the cultural heritage environment and atmosphere. These cultural products and activities encourage to evoke a feeling of journeying through time and space, as tourists experience the enchanting film-themed settings (Meng & Tung, Citation2016). This perspective aligns with the idea that authenticity can become a kind of fantasy, a narrative that helps us make sense of a feeling that something important is missing from our lives (Knudsen et al., Citation2016). By staging the cultural heritage features, Hengdian World Studios creates a hyper-real travel environment that includes film-related tourism products, cultural heritage tourism products, and entertainment tourism products. Tourism becomes a game with multiple realities, which adds to the overall experience of the tourists (Baudrillard, Citation1983; Eco, Citation1983; Lovell & Bull, Citation2019; Urry, Citation1990).

Figure 7. A group of studio staff, who were dressed in different Chinese cultural and traditional costumes, worked in the ‘Tourist Service’ centre. Source: Photo by the authors, 2020.

Although the cultural heritage elements presented to tourists are not objectively and historically authentic, Hengdian World Studios actually does not attempt to cover up such a fact. Conversely, Hengdian World Studios acknowledges that its tourism sites are reproductions of real heritage sites, even though some tourists may still mistake the simulations for the real ones. For instance, Hengdian World Studios’ official website describes the ‘New Yuanmingyuan’ film studio as a ‘research and practical education base’ (Hengdian World Studios, Citationn.d.). The focus of these tourism sites is not on the objective authenticity of the physical objects being exhibited, but rather on the meanings and values of Chinese history and cultural heritage that they convey. Hengdian World Studios brands these tourism sites as alternative physical sources and carriers to educate tourists about Chinese history and traditional culture, encouraging them to experience cultural heritage tourism at film-related tourism sites.

Tourists’ understandings of their authentic experiences at Hengdian World Studios

The aim of doing interviews was to gain insights into these participants’ experiences and opinions regarding experiencing cultural heritage tourism at film-related tourism sites. Questions were divided into two topics:

If tourists believe that they can learn about Chinese traditional culture and history when visiting Hengdian World Studios.

If tourists think that the cultural heritage objects showcased at Hengdian World Studios have the capability to show the value and significance of Chinese cultural heritage and history?

A total of 50 participants were interviewed to responding these two questions, some essential background information about the participants is shown in . By encouraging participants to reflect on their personal experiences and perceptions, a deeper understanding of authenticity in tourism can be gained.

Table 1. Background information of interview participants.

The purpose of Topic A was to investigate whether tourists agreed with the idea that the replicas at Hengdian World Studios could be used as alternative physical sources to educate tourists about Chinese culture and history, as stated on Hengdian World Studios’ official website. The responses from the 50 participants indicated varying attitudes towards this question, including positive, neutral, and negative responses (). Some representative answers from these participants were extracted and shown below.

Table 2. Interview participants’ attitudes towards interview Topic A.

As to the reasons why people can learn about Chinese traditional culture and history when visiting the simulations and reproductions of real heritage and historic sites at Hengdian World Studios, Participant 3 (female, 27 years old, domestic tourist) explained:

The historic architecture and settings at Hengdian World Studios are built and designed to be one-to-one replicas of the real sites, making them visually reliable for me to learn about history. Furthermore, in contrast to the Forbidden City, where some areas are inaccessible due to heritage protection and maintenance, Hengdian World Studios offers a better travel experience with more accessible areas and a variety of tourist activities.

Even though the cultural heritage objects at Hengdian World Studios are not real, the knowledge and information about Chinese history I learned when visiting these sites and settings is real.

Tourists can be physically close to the toured objects at Hengdian World Studios, which is something we usually cannot do at real heritage sites and historic districts. However, based on my knowledge of architecture, I have realised a number of incorrect designs and use of building materials at Hengdian World Studios that are contrary to historical and real heritage facts. These buildings were probably designed and constructed for filming purposes, so they may not be a reliable source for educating people about Chinese traditional culture and history.

These copies of real heritage sites for me have more entertaining functions and educational functions. I prefer to learn Chinese culture and history at real heritage sites.

Topic B was designed to elicit tourists’ perceptions of the similarities and differences between ‘real’ and ‘fake’ cultural heritage. The responses from the 50 participants indicated varying attitudes towards this question, including positive, neutral, and negative responses as well (). It also sought to understand the value and significance of simulations and reproductions of real heritage and historic sites. The answers revealed that tourists had different attitudes and perceptions towards the significance of simulated cultural heritage sites and the roles of these sites in making and re-making historical meaning and memories (Smith, Citation2006).

Table 3. Interview participants’ attitudes towards interview Topic B.

12 of 50 participants agreed that Hengdian World Studios could convey the value and significance of Chinese cultural heritage and history similarly to real sites. As Participant 11 (female, 24 years old, international tourist) stated ‘I do not really care if the sites I visit are objectively real or not, as long as I think they are real and have an educational function, then at least for me personally, they convey historical and cultural value.’ However, 33 other participants thought that in the way of delivering and conveying the meaning and value of Chinese traditional culture and history, the simulations and reproductions at Hengdian World Studios cannot be seen as ‘authentic’ as the real cultural heritage sites, even though Hengdian World Studios promotes itself as an ‘education base.’ Participant 26 (male, 72 years old, domestic tourist) in the interview explained ‘I could not experience a sense of history as I could in the real heritage sites.’ Participant 5 (female, 28 years old, domestic tourist) stated ‘without the accumulation of time [thousands of years] and without experiencing the real historic events, the simulations and replicas cannot stimulate me to have similar feelings as those when I visit the real ones.’ Participants 26 and 5 provided negative responses to both Questions A and B, while some other participants, for instance, Participants 7 (female, 18 years old, domestic tourist) and Participant 33 (male, 39 years old, international tourist) have inverse points of view to these two questions. While Participant 7 agreed that Hengdian World Studios could be used as a research base to learn Chinese history and culture, she suggested ‘I prefer to visit the real heritage and historic sites, because Hengdian World Studios is more suitable to experience film tourism and to have a very general view of history and culture.’ Similarly, Participant 33 stated:

It is not difficult to learn Chinese history and culture through visiting the copies, while I believe they are much different from real ones, which can better convey the value and significance of Chinese cultural heritage and history.

The buildings at the film studios only simulate the constructions, shapes and colours of real heritage sites, but they are essentially unrelated to real historical events and figures, and these simulations for me are more like buildings without a ‘historical soul.’

Although the participants in the case of Hengdian World Studios do not form a representative sample of the population of all tourists at Hengdian World Studios, the above responses can also demonstrate tourists’ various understandings of cultural heritage tourism at a film-related tourism site. We summarise the contributions of this study on the research of authenticity in tourism into three aspects.

Firstly, this study supports the viewpoint that tourists are a heterogeneous group (Cohen, Citation1988; Pearce, Citation1985), and every tourist has their own subjective judgement on the authenticity during the journey. In the case of Hengdian World Studios, tourists have been aware that they visited simulations and that the authenticity of the cultural heritage features and displays was staged by the destination, and have varying attitudes towards their travel experiences at Hengdian World Studios. Tourists’ perceptions of authenticity tend to be subjective, influenced by factors such as their educational background, previous travel experiences, and familiarity with real heritage sites and historic knowledge. In addition to this, this study also suggests, however, that influences of objective elements attached to a tourist site, such as the use of building material and scale of a simulation, on tourists’ judgements and evaluations of the authenticity cannot be overlooked.

Secondly, the interview data in this study highlights that tourists can have authentic cultural heritage travel experiences at objectively inauthentic and staged authentic sites. This can be reflected by the fact that most participants can learn about Chinese traditional culture and heritage through visiting the simulated cultural heritage sites at Hengdian World Studios. They believe that their travel experiences at film-related tourism sites are as authentic as those at real cultural heritage sites, despite being aware that what they see is staged, to some degree also suggesting that what the destination stages is contributing towards tourists having existentially authentic experiences.

This phenomenon confirms the viewpoint that some tourists understand that what they see and experience at a tourist site could not be ‘authentic,’ however they are still willing to participate in the touristic activities, or unconsciously believe what the destination stages and performs, as if it were authentic (Cohen, Citation1988; Vidon et al., Citation2018). This could be because for these tourists, their existential authentic experiences do not depend on the objective and staged facts of the tourism sites but on their subjective feelings and evaluations (Knudsen et al., Citation2016; Wang, Citation1999). Ultimately, the authenticity of the tourism products and travel environment lies in the eye of the beholder, and what may be staged and promoted as ‘authentic’ by destinations may not necessarily be viewed in the same way by tourists. It follows that tourism destinations strategically claim the authenticity of their tourist attractions and products, but tourists may subjectively judge it differently.

Thirdly, we suggest that although tourists can have authentic cultural heritage touristic experiences at film-related tourism sites, this does not mean that copies can serve as replacements or substitutions for real heritage and historic sites. This is reflected in the fact that most of the participants expressed that the copies at Hengdian World Studios can be used as film settings to tell stories that take place in specific Chinese past dynasties, but they cannot accurately and authentically convey the value and significance of Chinese history and culture in the same way as the real sites can. Some tourists indeed can recall memories and learn about history and culture by visiting either real or simulated cultural heritage sites. From this perspective, the exhibited objects themselves are not important. However, from the perspective of historical significance and value communication, the real and the ‘fake’ are intrinsically different, even if extrinsically they look the same.

This does not mean that Hengdian World Studios completely failed to stage the authenticity of its cultural heritage features, but tourists’ different attitudes towards real cultural heritage sites and simulations may stem from their deeper emotional connection to the real ones. According to Meng and Tung (Citation2016), ‘cultural familiarity’ with Chinese culture, heritage and history is domestic tourists’ main travel motivation to Hengdian World Studios. However, such familiarity can also be understood as the main reason why tourists insist that real cultural heritage and historic sites cannot be replaced by simulations. Specifically, as the interview data showed above, some participants considered the simulations in Hengdian World Studios to be less authentic than the real heritage sites because they lack a genuine ‘sense of history,’ ‘historical sense,’ or ‘historical soul.’ This judgement is somewhat abstract, and authenticity here tends to be more associated with the subjective perspective, in accordance with, for example, their personal beliefs, emotions, and cognitions.

Some tourists’ judgements are relatively more evidence-based and object-based, as they expressed that the simulated cultural heritage sites are the places without the accumulation of time and without experiencing real historical events and are not the authentic locations where real historic figures lived. Some tourists’ judgements are more knowledge-based, they could be aware of the incorrect designs and use of some building materials on its settings and architectures. Here, authenticity tends to be associated with objective (objective facts of the sites), performative (the destination’s performance and representation), and subjective perspective (the tourist’s background knowledge). In a word, Hengdian World Studios applies different ways to stage the authenticity for convincing tourists of their cultural heritage settings, which to some degree also contributes to promoting groups of tourists to have existentially authentic experiences. On the one hand, staged authenticity of cultural heritage sites at Hengdian World Studios does not mean the ‘inauthenticity’ of these sites, and may even promote the generation of tourists’ existential authenticity of their travel experiences. On the other hand, tourists’ judgments on authenticity when experiencing cultural heritage tourism is complicated. Although some tourists agree that they can understand and learn authentic historical knowledge through visiting the ‘fake’ heritage sites at film studios, it does not mean that for these tourists, the staged heritage sites have the same or similar functions on historical value transmission as real heritage sites. People still distinguish between the functions of real and staged cultural heritage sites. This means that Hengdian World Studios strategically stages the authenticity, but tourists have their own judgements on authenticity issues, and they are not completely influenced by what Hengdian World Studios stages, but are also influenced by their understandings, subjectivity, or/and knowledge. Therefore, this paper suggests that in tourism studies, authenticity can be studied from subjective, objective, and performative perspectives, which are often interconnected and intertwined in various circumstances.

Conclusion

This paper showed how simulated cultural heritage tourism is managed at a film-related tourism site and how tourists perceive whether their experiences are authentic or not, based on the case of Hengdian World Studios (China), the world’s largest outdoor film studio and film shooting base. Using ethnographic methods, including site visits conducted between 2018 and 2023 and online interviews conducted in 2020 and 2023 with 50 participants who had previously visited Hengdian World Studios, this paper examined how the destination stages the authenticity of its cultural heritage tourism and how tourists understand the authenticity of their cultural heritage tourism experiences at film-related tourism sites.

Based on the ethnographic data, this study suggests that the destination employs various strategies to stage and perform its cultural heritage elements, including simulating real heritage and historic sites in high quality and reproducing destroyed, vanished, and non-existing heritage and historic sites. Based on the interview data, this paper has contributed to research on tourists’ perceptions of authenticity in tourism in three aspects, and research on tourists’ perceptions of authenticity in tourism by highlighting three aspects. Firstly, tourists can have subjective judgments on the representations of authenticity and their authentic experiences. Secondly, a group of tourists can have existential authentic travel experiences even if visiting objectively inauthentic and staged authentic cultural heritage sites. Thirdly, some tourists do not believe that simulations can show the value and highlight the significance of Chinese history and culture as real heritage and historic sites do, even though they had ‘authentic’ experiences at the destination. This study suggests that authenticity indeed is negotiable and malleable, but this does not necessarily mean tourists’ experiences are not authentic. The judgements here on authenticity are associated with the objective, performative, and/or subjective perspectives, which are intertwined and inter-connected in this case to research on the authenticity issues. Therefore, this study suggests that a destination can strategically claim ‘authenticity’ of its touristic elements, and tourists subjectively judge the authenticity.

To gain a deeper understanding of Hengdian World Studios’ film-related tourism and cultural heritage tourism, future research can employ quantitative methods to obtain a greater number of responses regarding tourists’ travel experiences, which may contribute to indicating people’s different attitudes and perceptions and making a cross comparison within and across each type of tourist. Researchers can also investigate the significance of experiencing Chinese cultural heritage at real heritage sites and the role that Hengdian World Studios plays in representing Chinese heritage.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Xin Cui

Dr Xin Cui is currently working as a post-doc researcher at the China Tourism Academy (Data Centre of Ministry of Culture and Tourism). Her research interests include tourists’ experience at media tourism destinations, issues of authenticity at media touristic sites and spaces, and integrated development of culture and tourism.

Ziqian Song

Dr Ziqian Song is currently working as the lead researcher at the China Tourism Academy (Data Centre of Ministry of Culture and Tourism). He mainly engages in research on tourism policy and integrated development of culture and tourism, and basic tourism theory.

References

- Agarwal, S., & Shaw, G. (2017). Heritage, screen and literary tourism. Channel View Publications.

- Andriotis, K. (2009). Sacred site experience. Annals of Tourism Research, 36(1), 64–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2008.10.003

- Baudrillard, J. (1983). Simulations. Semiotext (E), Cop.

- Beeton, S. (2011). Tourism and the moving image – incidental tourism promotion. Tourism Recreation Research, 36(1), 49–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2011.11081659

- Beeton, S. (2015). Travel, tourism and the moving image. Channel View Publications.

- Beeton, S. (2016). Film-induced tourism (2nd ed.). Channel View Publications.

- Bolan, P., Boy, S., & Bell, J. (2011). We’ve seen it in the movies, let’s see if it's true. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, 3(2), 102–116. https://doi.org/10.1108/17554211111122970

- Boyd, S. (2002). Cultural and heritage tourism in Canada: Opportunities, principles and challenges. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 3(3), 211–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/146735840200300303

- Brown, D. (1996). Genuine fakes. In T. Selwyn (Ed.), The tourist image: Myths and myth making in tourism: Myth and myth making in tourism (pp. 33–48). Wiley.

- Buchmann, A., Moore, K., & Fisher, D. (2010). Experiencing film tourism: authenticity & fellowship. Annals of Tourism Research, 37(1), 229–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2009.09.005

- Canavan, B., & McCamley, C. (2021). Negotiating authenticity: Three modernities. Annals of Tourism Research, 88, Article 103185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103185

- Chhabra, D., Healy, R., & Sills, E. (2003). Staged authenticity and heritage tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 30(3), 702–719. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0160-7383(03)00044-6

- China Highlight. (2021). 15 Interesting forbidden city facts you didn't know. https://www.chinahighlights.com/beijing/forbidden-city/forbidden-city-facts.htm.

- China Weekly Reading. (2020). Cultural Heritage in the New Era: Yuan Mingyuan and its international cultural Exchange. https://epaper.gmw.cn/zhdsb/html/2022-05/18/nw.D110000zhdsb_20220518_1-19.htm

- Cohen, E. (1988). Authenticity and commoditization in tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 15(3), 371–386. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(88)90028-x

- Connell, J. (2012). Film tourism – evolution, progress and prospects. Tourism Management, 33(5), 1007–1029. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.02.008

- Daugstad, K., & Kirchengast, C. (2013). Authenticity and the pseudo-backstage of agri-tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 43, 170–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2013.04.004

- Eco, U. (1983). Travels in hyperreality. Harcourt Brace Jovanovitch.

- Gotham, K. F. (2018). Tourism and culture. In L. Grindstaff, M. M. Lo, & J. R. Hall (Eds.), Routledge handbook of cultural sociology (pp. 592–599). Routledge.

- Halewood, C., & Hannam, K. (2001). Viking heritage tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 28(3), 565–580. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0160-7383(00)00076-1

- Hengdian Group. (2020). Corporate social responsibility report 2018–2020. https://www.hengdian.com/zh-cn/responsibility/reports

- Hengdian World Studios. (n.d.). Theme scenic areas. http://www.hengdianworld.com/en/Theme/

- IGI Global. (n.d.). What is cultural heritage tourism. https://www.igi-global.com/dictionary/challenges-for-promotion-of-heritage-tourism/56429

- Kaminski, J., Benson, A. M., & Arnold, D. (2013). Introduction. In J. Kaminski, A. M. Bensen, & D. Arnold (Eds), Contemporary issues in cultural heritage tourism (pp. 3–18). Routledge.

- Knudsen, D. C., Rickly, J. N., & Vidon, E. S. (2016). The fantasy of authenticity: Touring with Lacan. Annals of Tourism Research, 58, 33–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2016.02.003

- Kolar, T., & Zabkar, V. (2010). A consumer-based model of authenticity: An oxymoron or the foundation of cultural heritage marketing? Tourism Management, 31(5), 652–664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2009.07.010

- Lovell, J. (2019). Fairytale authenticity: Historic city tourism, Harry Potter, medievalism and the magical gaze. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 14(5–6), 448–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873x.2019.1588282

- Lovell, J., & Bull, C. (2019). Authentic and inauthentic places in tourism: From heritage sites to theme parks. Routledge.

- Lu, L., Chi, C. G., & Liu, Y. (2015). Authenticity, involvement, and image: Evaluating tourist experiences at historic districts. Tourism Management, 50(50), 85–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.01.026

- MacCannell, D. (1973). Staged authenticity: Arrangements of social space in tourist settings. American Journal of Sociology, 79(3), 589–603. https://doi.org/10.1086/225585

- Macionis, N. (2004). Understanding the film-induced tourist. In W. Frost, G. Croy, & S. Beeton (Eds.), International tourism and media conference proceedings (pp. 86–97). Tourism Research Unit, Monash University.

- Meng, Y., & Tung, Y. W. S. (2016). Travel motivations of domestic film tourists to the Hengdian World Studios: Serendipity, traverse, and mimicry. Journal of China Tourism Research, 12(3–4), 434–450. https://doi.org/10.1080/19388160.2016.1266068

- Moore, K., Buchmann, A., Månsson, M., & Fisher, D. (2021). Authenticity in tourism theory and experience. Practically indispensable and theoretically mischievous? Annals of Tourism Research, 89, Article 103208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103208

- Oviedo-García, M. A., Castellanos-Verdugo, M., Trujillo-García, M. A., & Mallya, T. (2016). Film-induced tourist motivations. The case of Seville (Spain). Current Issues in Tourism, 19(7), 713–733. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2013.872606

- Pearce, D. G. (1985). Tourism today. A geographical analysis. Longman Scientific & Technical.

- Piazzoni, M. F. (2018). The real fake. Fordham University Press.

- Poria, Y., Butler, R., & Airey, D. (2003). The core of heritage tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 30(1), 238–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0160-7383(02)00064-6

- Reijnders, S. (2011). Places of the imagination: Media, tourism, culture. Ashgate.

- Richards, G. (1996). Cultural tourism in Europe. CABI.

- Rickly, J. M. (2022). A review of authenticity research in tourism: Launching the Annals of Tourism Research curated collection on authenticity. Annals of Tourism Research, 92, Article 103349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103349

- Rittichainuwat, B., Laws, E., Scott, N., & Rattanaphinanchai, S. (2017). Authenticity in screen tourism: Significance of real and substituted screen locations. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 42(8), 1274–1294. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348017736568

- Smith, L. (2006). Uses of heritage. Routledge.

- Steiner, C. J., & Reisinger, Y. (2006). Understanding existential authenticity. Annals of Tourism Research, 33(2), 299–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2005.08.002

- Su, S. (2008). Not pursuing the eternal existence of authentic building – on 'pseudo-antique’ building from the dispute on rebuilding Yuanming Yuan. Architectural Forum, 8, 92–94.

- Urry, J. (1990). The tourist gaze: Leisure and travel in contemporary societies. Sage.

- Vidon, E. S., Rickly, J. M., & Knudsen, D. C. (2018). Wilderness state of mind: Expanding authenticity. Annals of Tourism Research, 73, 62–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2018.09.006

- Wang, N. (1999). Rethinking authenticity in tourism experience. Annals of Tourism Research, 26(2), 349–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0160-7383(98)00103-0

- Yen, C.-H., & Croy, W. G. (2016). Film tourism: Celebrity involvement, celebrity worship and destination image. Current Issues in Tourism, 19(10), 1027–1044. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2013.816270

- Zeng, C., & Wu, M. (2019). From filming bases to red tourism attraction, leading people’s cultural life and daily lifestyle. https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/S93MMDWcgVWMwAzOlwqt9w

- Zhu, Y. (2012). Performing heritage: Rethinking authenticity in tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(3), 1495–1513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2012.04.003