ABSTRACT

In order to understand both developmental and proximal contributors to self-forgiveness, we examined the simultaneous effects of childhood adversity (i.e. unpredictability and harshness) and current experiences of divine forgiveness on self-forgiveness in young adulthood across two studies. As expected, childhood unpredictability was negatively, and divine forgiveness was positively associated with self-forgiveness in both Study 1 (N = 439) and Study 2 (N = 441). Childhood harshness was not associated with self-forgiveness. In Study 2, we found that self-control mediates the relationships between childhood unpredictability and self-forgiveness and between divine forgiveness and self-forgiveness. Results suggest that childhood unpredictability undermines, whereas divine forgiveness bolsters self-forgiveness by weakening and shoring up regulatory resources, respectively. Limitations and future directions are discussed.

Self-forgiveness is essential to psychological well-being (e.g. Ercengiz et al., Citation2022; Fincham & May, Citation2020, Citation2022; Kim et al., Citation2022; Massengale et al., Citation2017; Toussaint et al., Citation2016). Understanding the antecedents, both developmental and proximate, of self-forgiveness is thus an important empirical goal. Some research suggests that adverse childhood experiences may undermine downstream interpersonal forgiveness (e.g. Kaufman et al., Citation2019; McCullough et al., Citation2013; Rahmandani et al., Citation2022), but less work has focused on self-forgiveness and childhood environmental factors other than trauma that are associated with socioemotional functioning – namely, unpredictability and harshness. One promising proximal factor that may enhance self-forgiveness for those who believe in a higher power is divine forgiveness (Fincham & May, Citation2022; McConnell & Dixon, Citation2012). That is, the more people experience divine forgiveness, the more they engage in self-forgiveness. The current work tests whether and to what extent childhood unpredictability and harshness and current experiences of divine forgiveness contribute to adults’ tendency to forgive themselves after a perceived transgression. Furthermore, we test whether self-control mediates the associations between adversity and self-forgiveness and between divine forgiveness and self-forgiveness, given that adversity may undermine, and divine forgiveness may buttress self-regulation, which supports forgiveness.

Adverse childhood events and forgiveness

Adversity in childhood has been linked to less downstream interpersonal forgiveness: The more adverse childhood events individuals experienced, the less forgiving they were of others (Rahmandani et al., Citation2022). Moreover, men who experienced family neglect, conflict, and violence, and who were exposed to neighborhood crime in their childhoods tended to engage in exploitative and retaliatory behavior, rather than forgiving those who wronged them (McCullough et al., Citation2013). These unforgiving and harsh attitudes and tendencies are also directed inwardly. Adversity in childhood has also been linked to lower self-compassion and self-reassurance, and higher self-criticism, self-hatred, and shame (Naismith et al., Citation2019), and less forgiveness of themselves for transgressions (Rahmandani et al., Citation2022). Notably, lower levels of self-forgiveness mediated the link between higher adversity and higher depression (Rahmandani et al., Citation2022). It makes sense, then, that forgiveness and forgiveness therapy are so effective for buffering against adversity in the family (for review, see Fincham, Citation2017) and adverse childhood events (Song et al., Citation2021; Yu et al., Citation2021). Indeed, research finds that increased forgiveness is positively associated with posttraumatic growth for people who experienced high levels of childhood adversity (Amaranggani & Dewi, Citation2022).

But what is the role of childhood adversity that does not entail trauma? Theory and empirical work applying a behavioral ecology framework suggest that for understanding adult psychosocial and emotional functioning there are two especially important early childhood environmental factors – harshness and unpredictability (Belsky et al., Citation2012; Brumbach et al., Citation2009; Ellis et al., Citation2009). Environmental harshness denotes the risk of morbidity/mortality in the environment; for people, particularly in the Western world, socioeconomic resources inversely relate to mortality/morbidity. That is, higher harshness is captured by lower economic resources (Maranges et al., Citation2022, Citation2023; Mittal et al., Citation2015). Unpredictability is most often operationalized as instability in the childhood social and physical environment, such as within the family, in the neighborhood, and at school (Maranges et al., Citation2022, Citation2023; Mittal et al., Citation2015). Unpredictability in the environment presents individuals with random changes in the local mortality/morbidity risk.

Little work has been done to elucidate how childhood harshness and unpredictability are related to downstream forgiveness processes, much less self-forgiveness. In a cross-national sample of people with lower socioeconomic resources (higher harshness), people ranked forgiveness as a relatively unimportant facet to their quality of life (Skevington, Citation2009). Prior work suggests that people who have experienced higher levels of unpredictability in childhood tend to be less practically and emotionally invested in other people’s well-being and their relationships and are, in turn, less prosocial (Maranges et al., Citation2021; Zhu et al., Citation2018). Hinting more strongly at associations with forgiveness, childhood unpredictability was negatively associated with the Light Triad of personality, which includes Humanism, Kantianism, and Faith in Humanity; one facet of faith in humanity is forgiveness of others (Kaufman et al., Citation2019). Faith in humanity has also been linked to individuals’ helping others who have wronged them (Ruel et al., Citation2023). It would be reasonable to expect that childhood harshness and unpredictability are associated with less self-forgiveness in adulthood to the extent that self-forgiveness recruits the same socioemotional processes affected by trauma and which are associated with interpersonal forgiveness; however, no prior work has established how these childhood environmental factors relate to self-forgiveness. Thus, assessing the links between childhood unpredictability and harshness and self-forgiveness, as well as what might explain these links, is a primary goal of this research.

Divine forgiveness and self-forgiveness

A growing literature suggests that a fuller understanding of the psychology of forgiveness entails focusing also on divine forgiveness (e.g. Fincham & May, Citation2022; Fincham & May, Citation2023b). Divine forgiveness can be understood as the experience of absolution for a wrongdoing from a higher power, and such an experience is evident in the person’s thinking, affect, and behavior (Fincham & May, Citation2022). Religiosity is associated with greater self-forgiveness (e.g. Fincham et al., Citation2020), and this may be due in part to divine forgiveness engendering self-forgiveness. Indeed, several studies demonstrate that divine forgiveness predicts self-forgiveness, both concurrently and longitudinally (e.g. Fincham & May, Citation2022; Fincham & May, Citation2023a; Kim et al., Citation2022; McConnell & Dixon, Citation2012). However, empirical work is still to be done to test potential mechanisms of this divine and self-forgiveness link. One such mechanism may be self-control.

The role of self-control

Self-control may account for the negative effects of childhood unpredictability and harshness and the positive effects of divine forgiveness on self-forgiveness. Recent work demonstrates that self-regulation facilitates forgiveness of others in the context of intimate relationships: the higher individuals’ self-control, the better able they were to forgive their relationship partners after transgressions (Ho et al., Citation2023). Moreover, self-forgiveness is viewed as difficult and requiring effort (Fisher & Exline, Citation2006) and has been linked to emotion regulation (Hodgson & Wertheim, Citation2007). Self-forgiveness may thus require self-regulation. Childhood unpredictability and harshness have been associated with lower self-regulatory abilities (e.g. lower self-control and emotional control, and higher impulsivity and risk taking) in adolescence and adulthood, however (Doom et al., Citation2016; Griskevicius et al., Citation2011; Maranges et al., Citation2021, Citation2022; Szepsenwol et al., Citation2022). In contrast, experiencing divine forgiveness may shore up regulatory resources. Religiosity is positively associated with self-control (for review, see Hardy et al., Citation2020; McCullough & Willoughby, Citation2009), and some have suggested that ‘religious beliefs (via divine forgiveness) regulate emotion’ (Hsu, Citation2021, p. 2067). Indeed, work with latter day saints concludes that ‘religious repentance processes can lead to lasting change and that such beliefs and processes can aid in the process of moral self-regulation’ (Hendricks et al., Citation2023; p. 78). Together, that work suggests, and we test whether, childhood adversity is associated with less self-forgiveness and divine forgiveness is associated with more self-forgiveness through self-control.

The current work

Across two studies, we test whether childhood unpredictability and harshness as well as divine forgiveness are associated with self-forgiveness in adulthood. We expect that the childhood adversity factors will be negatively associated with, whereas divine forgiveness will be positively associated with self-forgiveness, including as simultaneous contributors. Self-control may serve as the mechanism by which childhood adversity and divine forgiveness predict self-forgiveness. We test that possibility via path mediation analyses in Study 2. To ensure that the results do not simply reflect the broader effect of religiosity, across both studies we statistically control for this variable to demonstrate that divine forgiveness is associated with self-control and self-forgiveness above and beyond religiosity.

Study 1

We tested whether and to what extent childhood unpredictability, childhood harshness, and experiences of divine forgiveness are associated with the tendency to self-forgive in adults. The childhood factors and divine forgiveness may independently contribute to self-forgiveness, such that the tendency to forgive oneself after a transgression is shaped additively by both childhood experiences and by the experience of divine forgiveness. Alternatively, these factors may interact, such that divine forgiveness serves as a direct buffer against the effects of challenging childhood environments on self-forgiveness.

Method

Participants and procedure

Four hundred and thirty-nine (N = 439) undergraduate students at a large southeastern U.S. public university taking courses in social sciences participated in the study. Participation in the study was one option for earning class extra credit. Students who indicated a belief in a higher power or God were included in the study. Participants were adults (Mage = 19.91, SD = 1.81; ranging from 18 to 46; 396 women, 43 men) who identified as White (n = 296), Latina/o (n = 60), African American or Black (n = 46), mixed race (n = 19), Asian (n = 10), American Indian or Alaska Native (n = 2), Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander (n = 1), Middle Eastern (n = 1), or preferred not to say (n = 4). Note that participants could identify as more than one race/ethnicity. Participants identified primarily as Christian (Protestant, Catholic, etc.; n = 353); participants also identified as Jewish (n = 19), Jewish and Catholic (n = 2), Muslim (n = 2), Christian and Muslim (n = 1), Buddhist (n = 2), Traditional/Native African Spirituality (n = 1), Hindu (n = 1), Hindu and Christian (n = 1), and Latter Day Saint (n = 1). Many participants did not identify with any specific religion (n = 56).

As part of an online survey, participants reported their demographics before responding to measures of childhood unpredictability, childhood harshness, divine forgiveness, and self-forgiveness. Data on religiosity were also collected so that we could statistically control for it. For both studies, research methods were approved by the local IRB and no data were collected before approval (Florida State University IRB, #3600).

Materials

Childhood unpredictability

The childhood unpredictability scale included 15 items, such as My family life was generally inconsistent and unpredictable from day-to-day, I could not predict which of many caretakers (e.g. babysitters, nannies, neighbors, family) would be watching me, and When I left my house I was never quite certain what would happen in my neighborhood (Maranges et al., Citation2021, Citation2022). Participants responded on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) rating scale. Items were averaged (M = 3.05, SD = 1.41, α = .92).

Childhood harshness

The childhood harshness scale included 11 items, including for example, My family was strained financially, We had to try to save money when shopping for anything, and I grew up in a relatively wealthy neighborhood (reversed). Responses were provided on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) scale and were averaged across items (M = 1.92, SD = .99, α = .93).

Divine forgiveness

Participants responded to a 5-item divine forgiveness measure (Fincham & May, Citation2022, Citation2022) on a scale from 1 to 4. Items include How often have you felt that God forgives you?, How often do you experience situations in which you have the feeling that God is merciful to you?, How often do you experience situations in which you have the feeling that God delivers you from a debt? With response range from never to always or almost always, and I am certain that God forgives me when I seek His forgiveness and Knowing that I am forgiven for my sins gives me the strength to face my faults with response range from strongly disagree to strongly agree. We averaged the five items of the divine forgiveness scale (M = 2.42, SD = .38, α = .88).

Self-forgiveness

Participants responded to a 6-items tapping the tendency to forgive oneself (Fincham & May, Citation2019). Specifically, participants rated their agreement with items such as I feel badly at first when I hurt someone but I am soon able to forgive myself and I have a tendency to hold grudges towards myself (reversed) on a 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree). The six items were averaged to create our measure of self-forgiveness (M = 3.00, SD = .71, α = .71).

Religiosity

We assessed religiosity via 2 items on an 8-point scale (see Pearce et al., Citation2017). The first item asked How important is religion in your life? With response range not at all to extremely. The second item asked, In general, how often do you attend religious services or meetings? With response range never to about once a day. We averaged the two items to create the control measure of religiosity (M = 4.36, SD = 1.90, α = .77).

Results and discussion

First, we assessed the bivariate associations of the childhood factors of unpredictability and harshness and divine forgiveness with self-forgiveness. Correlations among all variables can be found in . As expected, childhood unpredictability was negatively associated with, whereas divine forgiveness was positively associated with self-forgiveness. Childhood harshness was not associated with self-forgiveness, however.

Table 1. Correlations among variables, Study 1.

Based on those results, we next assessed via hierarchical regression analyses the relative contributions of childhood unpredictability (centered) and divine forgiveness (centered) (step 1) and their interaction (step 2). See . When accounting for both, the effect of childhood unpredictability became nonsignificant, while the effect of divine forgiveness remained significant. The interaction between the two was not significant. When controlling for the effect of religiosity, β = −.15, t(432) = −2.59, p = .010, the same pattern of results emerged: childhood unpredictability, β = −.11, t(432) = −1.68, p = .094; divine forgiveness, β = .27, t(432) = 4.83, p < .001; interaction, β = .02, t(432) = .56, p = .574.

Table 2. Hierarchical multiple regression analysis testing whether childhood unpredictability, divine forgiveness, and their interaction predict self-forgiveness, Study 1.

Results of this study suggest that both childhood experiences of unpredictability and experiences of divine forgiveness related to forgiveness of the self in adulthood, but divine forgiveness captures variance over and beyond that of unpredictable childhood experiences. The implication is that even when considering the negative effect of childhood unpredictability on self-forgiveness, divine forgiveness may play an important role in bolstering self-forgiveness. It is important to replicate this pattern as well as to discern whether the effects of childhood unpredictability and divine forgiveness on self-forgiveness are due to their opposing effects on self-control.

Study 2

Study 1 established that childhood unpredictability and the experience of divine forgiveness are associated with self-forgiveness but in opposite directions. The aim of Study 2 was to test whether and to what extent self-control accounts for these effects. We expected that people who experienced more unpredictability in their childhoods would have lower self-control, and, in turn, be less forgiving of themselves. Simultaneously counteracting that pathway, we expected that divine forgiveness would be positively associated with self-control, which supports self-forgiveness.

Method

Participants and procedure

Participants were 441 undergraduate students taking courses in social sciences at a large southeastern U.S. public university and received a small amount of extra credit in a class. We only included respondents who indicated a belief in a higher power or God. Participants (Mage = 19.88, SD = 1.67; ranging from 18 to 42; 403 women, 33 men, 2 non-binary, 1 genderfluid, 2 prefer not to say) identified as White (n = 297), Latina/o (n = 47), African American or Black (n = 45), mixed race (n = 27), Asian (n = 16), American Indian or Alaska Native (n = 2), Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander (n = 1), Middle Eastern/North African (n = 1), Black and Latino (n = 1), White and Latina (n = 1), or preferred not to say (n = 3). With respect to religious affiliations, participants were Christian (Protestant, Catholic, etc.; n = 325), Jewish (n = 19), Muslim (n = 3), Buddhist (n = 3), Jewish and Catholic (n = 1), and Hindu (n = 1), or did not identify with any specific religion (n = 83).

Participants provided their demographics and responded to measures of childhood unpredictability, childhood harshness, divine forgiveness, self-control, self-forgiveness, and religiosity. Research methods were approved by the local IRB and no data were collected before approval.

Materials

Participants responded to the same measures used in Study 1: childhood unpredictability (M = 1.88, SD =,97 α = .91), childhood harshness (M = 3.17, SD = 1.37, α = .92), divine forgiveness (M = 3.19, SD = .84, α = .92), self-forgiveness (M = 2.60, SD = .71, α = .68), and religiosity (M = 4.08, SD = 2.02, α = .78). Note that for the self-forgiveness scale, reliability analyses suggested that the reverse coded item I have a tendency to hold grudges towards myself reduced the reliability of the scale, such that we removed it. New to this study was the measure of self-control.

Self-control

Self-control was assessed with the 13-item brief self-control scale (Tangney et al., Citation2004). Participants responded to items such as I am able to work efficiently toward long-term goals, I refuse things that are bad for me, and I am lazy (reversed) on a 1 (not at all like me) to 5 (very much like me) scale. Items were averaged (M = 3.35, SD = .68 α = .86).

Results and discussion

First, we assessed the bivariate correlations among the measures of childhood unpredictability and harshness, divine forgiveness, self-control, and self-forgiveness. Correlations among all variables can be found in . Consistent with hypotheses and replicating Study 1, childhood unpredictability was negatively associated with, whereas divine forgiveness was positively associated with self-forgiveness. Again, childhood harshness was unrelated to self-forgiveness. As expected, childhood unpredictability and harshness were negatively correlated with self-control, suggesting that people who had challenging childhoods have lower self-control as adults. Divine forgiveness was positively associated with self-control, such that the more people experienced a higher power’s forgiveness, the more self-control they had.

Table 3. Correlations among variables, Study 2.

Next, we assessed the relative contributions of childhood unpredictability (centered) and divine forgiveness (centered) (step 1) and their interaction (step 2) via hierarchical regression analyses. See . Both childhood unpredictability and divine forgiveness remained significant predictors of self-forgiveness, but they did not interact. When controlling for religiosity, β = −.06, t(439) = −1.10, p = .274, the same pattern of results emerged: childhood unpredictability, β = −.13, t(439) = −2.83, p = .05; divine forgiveness, β = .16, t(439) = 2.68, p = .008; interaction, β = .04, t(439) = .90, p = .369. These results suggest that people who had unpredictable childhoods are less forgiving of themselves in adulthood. Independent of that effect, the experience of divine forgiveness positively supports self-forgiveness, insofar as they are positively and significantly associated.

Table 4. Hierarchical multiple regression analysis testing whether childhood unpredictability, divine forgiveness, and their interaction predict self-forgiveness, Study 2.

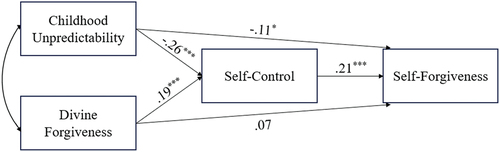

Finally, we tested whether the opposing effects of childhood unpredictability and divine forgiveness are simultaneously mediated by self-control. That is, we expected that childhood unpredictability would be associated with lower self-control and, therefore, self-forgiveness, whereas divine forgiveness would be positively associated with higher self-control, and, therefore, self-forgiveness. To test this mediation model, we employed a path analysis via AMOS 29 (Arbuckle, Citation2023) with childhood unpredictability and divine forgiveness both predicting self-forgiveness directly and as mediated through self-control. See .

Figure 1. Path analysis testing the mediating role of self-control in linking childhood unpredictability and divine forgiveness to self-forgiveness.

Indirect effects were assessed via 5000-sample bootstrapping. Self-control partially mediated the link between childhood unpredictability and self-forgiveness: The indirect effect of self-control was significant, b = −.03, 95% CI [−.048, −.013], S.E. = .009, p < .001, while the direct effect remained significant (represented in ). For divine forgiveness, the mediating effect of self-control on self-forgiveness, b = .02, 95% CI [.011, .045], S.E. = .009, p < .001, reduced the direct effect to nonsignificant (represented in , p = .156). The pattern of findings was the same when religiosity was included as a control variable.

Study 2 replicated results of Study 1, while finding a stronger effect of childhood unpredictability that remained significant when taking into account divine forgiveness. Specifically, childhood unpredictability was negatively associated with, while divine forgiveness was positively associated with adults’ tendency to forgive themselves. Study 2 also offered insight on one mechanism by which childhood unpredictability and divine forgiveness may be linked to self-forgiveness – self-control. The implication is that although childhood unpredictability and experience of divine forgiveness independently predict self-forgiveness, they do so through opposite effects on self-control. An unpredictable childhood is associated with degraded self-control, but divine forgiveness is associated with bolstered self-control, and self-control is likely an important antecedent of forgiving oneself.

General discussion

Self-forgiveness is an integral part of personal well-being (e.g. Fincham & May, Citation2020; Kim et al., Citation2022). Illuminating the developmental and proximal predictors of self-forgiveness is thus paramount for understanding who is likely to or unlikely to experience the benefits of self-forgiveness. Across two studies, the current work tested and found evidence consistent with the idea that childhood unpredictability may undermine, and divine forgiveness support, self-forgiveness. The opposite effects of childhood unpredictability and divine forgiveness were mediated by self-control: People who experienced higher, versus lower, levels of childhood unpredictability were lower in self-control, and, in turn, lower in self-forgiveness. Simultaneously, the more that people experienced divine forgiveness, the more self-control they had, which positively contributed to self-forgiveness. This suggests that childhood experiences of unpredictability and current experiences of divine forgiveness independently contribute to self-forgiveness, which appears to be a psychologically demanding process that requires self-regulation.

Adding to a growing body of work suggesting that childhood unpredictability and harshness differentially affect downstream personal and social health outcomes, harshness was not associated with self-forgiveness whereas unpredictability was. Other work suggests that unpredictability, not harshness, is associated with poorer psychological well-being (e.g. Maner et al., Citation2023; Martinez et al., Citation2022) and weaker prosocial tendencies (e.g. Chen, Citation2018; Maranges et al., Citation2021; Wu et al., Citation2017). In light of the current findings, it may be that people who experience high childhood unpredictability face more mental health challenges and engage in fewer other-focused psychosocial strategies because they must cope with the negative affect associated with what they perceive as their social and moral failings. Put another way, a lack of self-forgiveness by people who experienced unpredictable childhoods may act as a risk factor for poor psychological and social health. Indeed, lower self-forgiveness is associated with lower self-esteem and less well-being (Yao et al., Citation2017), especially for people who have experienced chronic stress (Toussaint et al., Citation2016). Lower self-forgiveness is also associated with poorer quality romantic relationships characterized by partners’ feeling less satisfied (Pelucchi et al., Citation2013). Future research should examine whether lower self-forgiveness accounts for the relationships between childhood unpredictability and downstream mental and social health outcomes.

This work also replicates the finding that divine forgiveness is positively associated with self-forgiveness, while proffering the additional insights that this occurs independently of an individual’s childhood experiences of unpredictability and through higher levels of self-control. But this is not to say that self-regulatory processes are the only reasonable mechanism by which divine forgiveness contributes positively to self-forgiveness. One set of alternative potential mechanisms by which divine forgiveness may engender self-forgiveness is guilt and shame. Shame entails appraising oneself as negative and problematic, whereas guilt entails appraising one’s behaviors as negative and problematic after a transgression (Tangney & Dearing, Citation2003; Tangney et al., Citation2007). As a result, shame and guilt give rise to different motivational tendencies. When people experience shame, they tend to avoid dealing with the transgression, such as by withdrawing socially (DeLong & Kahn, Citation2014) or refusing to accept responsibility (Fisher & Exline, Citation2006). In contrast, feelings of guilt seem to encourage people to engage in approach strategies to deal with the transgression, including by taking responsibility (Fisher & Exline, Citation2006), apologizing (Howell et al., Citation2012), and changing behavior (Tangney et al., Citation2014). It may be that when people feel forgiven by the divine, their shame decreases, removing the avoidance barrier to engaging in the self-forgiveness process. Indeed, Hall and Fincham (Citation2005) proposed that shame may preclude self-forgiveness, which has been borne out empirically in work demonstrating that shame-proneness is negatively related to self-forgiveness tendencies (Carpenter et al., Citation2016).

Considering guilt as a mediator between divine forgiveness and self-forgiveness may be a little more complicated. As Hall and Fincham (Citation2005) suggested, guilt (namely, guilt-proneness) has been linked to more self-forgiveness through conciliatory behaviors, as well as through behavioral change (Carpenter et al., Citation2016). However, it is unclear whether divine forgiveness reduces feelings of guilt, which is theorized to be one of many factors that drive seeking divine forgiveness (Fincham & May, Citation2022). Feelings of guilt may then simultaneously motivate seeking both self- and divine forgiveness. Alternatively, or in tandem, gaining the forgiveness of God may decrease the negative affect associated with guilt while also boosting its concomitant approach motivation that is associated with regaining moral standing. Theoretically, such a distinction may parallel the dual benefits of self-forgiveness itself: restoration of personal esteem and reorientation toward positive values (Griffin et al., Citation2018). This distinction specifically, as well as whether shame and guilt link divine forgiveness to self-forgiveness, should be assessed in future research.

Although the results of the current work replicate across two well-powered studies, there are a few limitations to consider in drawing conclusions. First, the majority of participants were mostly White, college aged, Christian women. Second, the present investigation relied on retrospective reports of childhood environments. Although retrospective reports of childhood experiences have the strength of capturing the perceptions that are likely proximal to the psychological experience of self-forgiveness, they may be vulnerable to biased memories or socially desirable responding. Finally, we assessed variables concurrently. Accordingly, future research should aim to replicate the finding that childhood unpredictability and divine forgiveness predict self-forgiveness in opposite directions through self-control in more diverse samples and longitudinally, to both capture unpredictability in childhood and to assess how childhood environments and divine forgiveness predict self-control and self-forgiveness over time.

Notwithstanding those limitations, this work is the first to demonstrate that childhood unpredictability and divine forgiveness are associated with self-forgiveness through self-control but in opposite directions. People who experienced highly unpredictable childhoods have lower self-control as adults, and, in turn, tend to be less forgiving of their own transgressions. Simultaneously, though, divine forgiveness may bolster self-control, which is associated with more self-forgiveness. This work underscores that early developmental context is important in shaping, and divine forgiveness is important in encouraging self-forgiveness, which is a demanding process that requires self-regulation.

Open scholarship

This article has earned the Center for Open Science badges for Open Data and Open Materials through Open Practices Disclosure. The data and materials are openly accessible at https://osf.io/7qhda/?view_only=849a24f071f9445dacab231bebf96a26

This article has earned the Center for Open Science badges for Open Data and Open Materials through Open Practices Disclosure. The data and materials are openly accessible at https://osf.io/7qhda/?view_only=849a24f071f9445dacab231bebf96a26

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data will be shared upon reasonable request.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Amaranggani, A. P., & Dewi, K. S. (2022, September). The role of forgiveness in post-traumatic growth: A cross-sectional study of emerging adults with adverse childhood experiences. Proceedings of International Conference on Psychological Studies (ICPSYCHE), Central Java, Indonesia (Vol. 3, pp. 1–12).

- Arbuckle, J. L. (2023). Amos (version 29.0). IBM SPSS [Computer Program].

- Belsky, J., Schlomer, G. L., & Ellis, B. J. (2012). Beyond cumulative risk: Distinguishing harshness and unpredictability as determinants of parenting and early life history strategy. Developmental Psychology, 48(3), 662–673. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024454

- Brumbach, B. H., Figueredo, A. J., & Ellis, B. J. (2009). Effects of harsh and unpredictable environments in adolescence on development of life history strategies: A longitudinal test of an evolutionary model. Human Nature, 20(1), 25–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-009-9059-3

- Carpenter, T. P., Tignor, S. M., Tsang, J. A., & Willett, A. (2016). Dispositional self-forgiveness, guilt-and shame-proneness, and the roles of motivational tendencies. Personality and Individual Differences, 98, 53–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.04.017

- Chen, B. B. (2018). An evolutionary life history approach to understanding greed. Personality and Individual Differences, 127, 74–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.02.006

- DeLong, L. B., & Kahn, J. H. (2014). Shameful secrets and shame-prone dispositions: How outcome expectations mediate the relation between shame and disclosure. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 27(3), 290–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2014.908272

- Doom, J. R., Vanzomeren-Dohm, A. A., & Simpson, J. A. (2016). Early unpredictability predicts increased adolescent externalizing behaviors and substance use: A life history perspective. Development and Psychopathology, 28(4pt2), 1505–1516. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579415001169.

- Ellis, B. J., Figueredo, A. J., Brumbach, B. H., & Schlomer, G. L. (2009). Fundamental dimensions of environmental risk: The impact of harsh versus unpredictable environments on the evolution and development of life history strategies. Human Nature, 20(2), 204–268. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-009-9063-7

- Ercengiz, M., Safalı, S., Kaya, A., & Turan, M. E. (2022). A hypothetic model for examining the relationship between happiness, forgiveness, emotional reactivity and emotional security. Current Psychology, 42(21), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-02909-2

- Fincham, F. D. (2017). Translational family science and forgiveness: A healthy symbiotic relationship? Family Relations, 66(4), 584–600. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12277

- Fincham, F. D., & May, R. (2022). Divine forgiveness and well-being among emerging adults in the USA. Journal of Religion and Health, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-022-01678-3

- Fincham, F. D., & May, R. W. (2019). Self-forgiveness and well-being: Does divine forgiveness matter? The Journal of Positive Psychology, 14(6), 854–859. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2019.1579361

- Fincham, F. D., & May, R. W. (2020). Divine, interpersonal and self-forgiveness: Independently related to depressive symptoms? The Journal of Positive Psychology, 15(4), 448–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2019.1639798

- Fincham, F. D., & May, R. W. (2022). No type of forgiveness is an island: Divine forgiveness, self-forgiveness and interpersonal forgiveness. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 17(5), 620–627. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2021.1913643

- Fincham, F. D., & May, R. W. (2023a). Divine forgiveness and interpersonal forgiveness: Which comes first? Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 15(2), 167–173. https://doi.org/10.1037/rel0000418

- Fincham, F. D., & May, R. W. (2023b). Toward a psychology of divine forgiveness: 2. Initial component analysis. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 15(2), 174–183. https://doi.org/10.1037/rel0000426

- Fincham, F. D., May, R. W., & Carlos Chavez, F. L. (2020). Does being religious lead to greater self-forgiveness? The Journal of Positive Psychology, 15(3), 400–406. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2019.1615109

- Fisher, M. L., & Exline, J. J. (2006). Self-forgiveness versus excusing: The roles of remorse, effort, and acceptance of responsibility. Self and Identity, 5(2), 127–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860600586123

- Griffin, B. J., Worthington, E. L., Jr., Davis, D. E., Hook, J. N., & Maguen, S. (2018). Development of the self-forgiveness dual-process scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 65(6), 715–726. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000293

- Griskevicius, V., Tybur, J. M., Delton, A. W., & Robertson, T. E. (2011). The influence of mortality and socioeconomic status on risk and delayed rewards: A life history theory approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100(6), 1015–1026. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022403

- Hall, J. H., & Fincham, F. D. (2005). Self–forgiveness: The stepchild of forgiveness research. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 24(5), 621–637. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2005.24.5.621

- Hardy, S. A., Baldwin, C. R., Herd, T., & Kim-Spoon, J. (2020). Dynamic associations between religiousness and self-regulation across adolescence into young adulthood. Developmental Psychology, 56(1), 180–197. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000841

- Hendricks, J. J., Cazier, J., Nelson, J. M., Marks, L. D., & Hardy, S. A. (2023). Qualitatively exploring repentance processes, antecedents, motivations, resources, and outcomes in latter-day saints. Archive for the Psychology of Religion, 45(1), 61–84.

- Hodgson, L. K., & Wertheim, E. H. (2007). Does good emotion management aid forgiving? Multiple dimensions of empathy, emotion management and forgiveness of self and others. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 24(6), 931–949. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407507084191

- Ho, M. Y., Liang, S., & Van Tongeren, D. R. (2023). Self-regulation facilitates forgiveness in close relationships. Current Psychology, 43(3), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04504-5

- Howell, A. J., Turowski, J. B., & Buro, K. (2012). Guilt, empathy, and apology. Personality and Individual Differences, 53(7), 917–922. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.06.021

- Hsu, H. P. (2021). The psychological meaning of self-forgiveness in a collectivist context and the measure development. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 2059–2069.

- Kaufman, S. B., Yaden, D. B., Hyde, E., & Tsukayama, E. (2019). The light vs. dark triad of personality: Contrasting two very different profiles of human nature. Frontiers in Psychology, 467. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00467

- Kim, J., Ragasajo, L. J., Kolacz, R. L., Painter, K. J., Pritchard, J. D., & Wrobleski, A. (2022). The interplay between divine, victim, and self-forgiveness: The relationship between three types of forgiveness and psychological outcomes. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 50(4), 414–427. https://doi.org/10.1177/00916471211046226

- Maner, J. K., Hasty, C. R., Martinez, J. L., Ehrlich, K. B., & Gerend, M. A. (2023). The role of childhood unpredictability in adult health. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 46(3), 417–428. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-022-00373-8

- Maranges, H. M., Haddad, N., Psihogios, S., & Timbs, C. L. (2023). Behavioral ecology in psychology: Making sense of many conceptualizations and operationalizations. Manuscript in Preparation.

- Maranges, H. M., Hasty, C. R., Maner, J. K., & Conway, P. (2021). The behavioral ecology of moral dilemmas: Childhood unpredictability, but not harshness, predicts less deontological and utilitarian responding. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 120(6), 1696. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000368

- Maranges, H. M., Hasty, C. R., Martinez, J. L., & Maner, J. K. (2022). Adaptive calibration in early development: Brief measures of perceived childhood harshness and unpredictability. Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology, 8(3), 313–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40750-022-00200-z

- Maranges, H. M., & Strickhouser, J. E. (2022). Does ecology or character matter? The contributions of childhood unpredictability, harshness, and temperament to life history strategies in adolescence. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, 16(4), 313–329. https://doi.org/10.1037/ebs0000266

- Martinez, J. L., Hasty, C., Morabito, D., Maranges, H. M., Schmidt, N. B., & Maner, J. K. (2022). Perceptions of childhood unpredictability, delay discounting, risk-taking, and adult externalizing behaviors: A life-history approach. Development and Psychopathology, 34(2), 705–717. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579421001607

- Massengale, M., Choe, E., Davis, D. E., Worthington, E. L., & Wenzel, M. (2017). Self-forgiveness and personal and relational well-being. In L. Woodyat & B. J. Griffin (Eds.), Handbook of the psychology of self-forgiveness (pp. 101–113). Springer International Publishing/Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-60573-9_8.

- McConnell, J. M., & Dixon, D. N. (2012). Perceived forgiveness from God and self-forgiveness. Journal of Psychology & Christianity, 31(1), 31.

- McCullough, M. E., Pedersen, E. J., Schroder, J. M., Tabak, B. A., & Carver, C. S. (2013). Harsh childhood environmental characteristics predict exploitation and retaliation in humans. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 280(1750), 20122104. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2012.2104

- McCullough, M. E., & Willoughby, B. L. (2009). Religion, self-regulation, and self-control: Associations, explanations, and implications. Psychological Bulletin, 135(1), 69. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014213

- Mittal, C., Griskevicius, V., Simpson, J. A., Sung, S., & Young, E. S. (2015). Cognitive adaptations to stressful environments: When childhood adversity enhances adult executive function. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 109(4), 604.

- Naismith, I., Zarate Guerrero, S., & Feigenbaum, J. (2019). Abuse, invalidation, and lack of early warmth show distinct relationships with self‐criticism, self‐compassion, and fear of self‐compassion in personality disorder. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 26(3), 350–361. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2357

- Pearce, L. D., Hayward, G. M., & Pearlman, J. A. (2017). Measuring five dimensions of religiosity across adolescence. Review of Religious Research, 59(3), 367–393.

- Pelucchi, S., Paleari, F. G., Regalia, C., & Fincham, F. D. (2013). Self-forgiveness in romantic relationships: It matters to both of us. Journal of Family Psychology, 27(4), 541. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032897

- Rahmandani, A., Salma, S., Kaloeti, D. V., Sakti, H., & Suparno, S. (2022). Which dimensions of forgiveness mediate and moderate childhood trauma and depression? Insights to prevent suicide risk among university students. Health Psychology Report, 10(3), 177–190. https://doi.org/10.5114/hpr/150252

- Ruel, M. K., De’Jesús, A. R., Cristo, M., Nolan, K., Stewart-Hill, S. A., DeBonis, A. M., Goldstein, A., Frederick, M., Geher, G., Alijaj, N., Elyukin, N., Huppert, S., Kruchowy, D., Maurer, E., Santos, A., Spackman, B. C., Villegas, A., Widrick, K., Wojszynski, C., & Zezula, V. (2023). Why should i help you? A study of betrayal and helping. Current Psychology, 42(21), 17825–17834. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-02954-x

- Skevington, S. M. (2009). Conceptualising dimensions of quality of life in poverty. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 19(1), 33–50. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.978

- Song, M. J., Yu, L., & Enright, R. D. (2021). Trauma and healing in the underserved populations of homelessness and corrections: Forgiveness therapy as an added component to intervention. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 28(3), 694–714. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2531

- Szepsenwol, O., Simpson, J. A., Griskevicius, V., Zamir, O., Young, E. S., Shoshani, A., & Doron, G. (2022). The effects of childhood unpredictability and harshness on emotional control and relationship quality: A life history perspective. Development and Psychopathology, 34(2), 607–620. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579421001371

- Tangney, J. P., Baumeister, R. F., & Boone, A. L. (2004). High self‐control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. Journal of Personality, 72(2), 271–324.

- Tangney, J. P., & Dearing, R. L. (2003). Shame and guilt. Guilford press.

- Tangney, J. P., Stuewig, J., & Martinez, A. G. (2014). Two faces of shame: The roles of shame and guilt in predicting recidivism. Psychological Science, 25(3), 799–805. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613508790

- Tangney, J. P., Stuewig, J., & Mashek, D. J. (2007). Moral emotions and moral behavior. Annual Review of Psychology, 58(1), 345–372. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070145

- Toussaint, L., Shields, G. S., Dorn, G., & Slavich, G. M. (2016). Effects of lifetime stress exposure on mental and physical health in young adulthood: How stress degrades and forgiveness protects health. Journal of Health Psychology, 21(6), 1004–1014. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105314544132

- Wu, J., Balliet, D., Tybur, J. M., Arai, S., Van Lange, P. A., & Yamagishi, T. (2017). Life history strategy and human cooperation in economic games. Evolution and Human Behavior, 38(4), 496–505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2017.03.002

- Yao, S., Chen, J., Yu, X., & Sang, J. (2017). Mediator roles of interpersonal forgiveness and self-forgiveness between self-esteem and subjective well-being. Current Psychology, 36(3), 585–592. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-016-9447-x

- Yu, L., Gambaro, M., Song, J. Y., Teslik, M., Song, M., Komoski, M. C., Wollner, B., & Enright, R. D. (2021). Forgiveness therapy in a maximum‐security correctional institution: A randomized clinical trial. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 28(6), 1457–1471. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2583

- Zhu, N., Hawk, S. T., & Chang, L. (2018). Living slow and being moral: Life history predicts the dual process of other-centered reasoning and judgments. Human Nature, 29(2), 186–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-018-9313-7