ABSTRACT

Wildlife are natural resources utilised by many people around the world, both legally and illegally, for a wide range of purposes. This scoping review evaluates 82 studies nested in 75 manuscripts to provide an overview of the documented motivations and methodologies used, and to identify and analyse knowledge gaps in the motivations of illegal harvesters. Studies differ in what data is collected, often leaving out important contextual variables. We find 12 different motivations, frequently interlinked and multiple often play a role in the same harvesting incident. Motivations seemed to differ between taxa. Future research needs to move beyond a general description but recognise the complexity of the matter and allow for context-specific adjustments to facilitate a deeper understanding of these motivations.

1. Introduction

Wildlife, plants and animals are a natural resource utilised by people around the world and can be used for subsistence (J. L. van Velden et al., Citation2020), medicine (Alves et al., Citation2013), collectables like pets or ornaments (Auliya, Altherr, et al., Citation2016; Nijman & Nekaris, Citation2014), or, in the case of timber, as construction materials (Brack, Citation2003). However, not all wildlife can be harvested legally, and frequently the harvest of these species can violate local or international legislation (Abi-Said et al., Citation2018; Arias et al., Citation2015; Janssen & Leupen, Citation2019). While illegal harvesting of wildlife has occurred throughout history, the impact remained relatively minimal and was often restricted geographically (Huxley, Citation2000). However, in recent years, wildlife crime, including illegal harvesting of wildlife, has become a highly lucrative market for transnational organised crime (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime [UNODC], Citation2016), often converging with other forms of organised crime (Anagnostou & Doberstein, Citation2022) and driving an increasing number of species towards extinction (Rija et al., Citation2020). Consequently, there has been an increasing interest in understanding what motivates people to harvest wildlife illegally to develop effective conservation measures (e.g. Lunstrum & Givá, Citation2020; Muth & Bowe, Citation1998; J. van Velden et al., Citation2018; Von Essen et al., Citation2014).

However, the reasons as to why people illegally harvest wildlife, often referred to as ‘poaching’, has been subject to debate (Duffy, Citation2016; Duffy & St John, Citation2013; Hope, Citation2002) with many different motivations mentioned, among, which i.e. poverty (Kühl et al., Citation2009; Stiles, Citation2011), food insecurity (Yamagiwa, Citation2003), economic interests (Eliason, Citation2012) and social disasters like war (Plumptre et al., Citation1997). The current understanding of these motivations seems to be hampered by a lack of empirical data (Duffy et al., Citation2016). In addition, motivations have been suggested as context-dependent, contradictory to each other (Lunstrum & Givá, Citation2020; J. van Velden et al., Citation2018), and sometimes regarded to be a social construct (Von Essen et al., Citation2014). Research on the motivations of illegal wildlife harvesting has attracted scholars from various disciplines (Lavadinović et al., Citation2021; Von Essen et al., Citation2014), often resulting in disciplinary silo thinking and as a result, the available evidence on documented motivations is highly heterogeneous and complex.

To gain a deeper understanding of the motivations behind illegal wildlife harvesting, it is paramount to analyse not only the motivations themselves, or the regional or species-specific trends but also the key characteristics of the study populations themselves. While studies such as Muth and Bowe (Citation1998) and Hübschle (Citation2017) have delineated motivations within specific geographic and biological contexts, others have focused on specific commodities (J. van Velden et al., Citation2018) or purposes (Lunstrum & Givá, Citation2020), these delineations only provide a context-specific view. Motivations for illegal harvesting are not monolithic; they vary considerably across different demographics, cultural backgrounds, and socio-economic statuses. For instance, Lavadinović et al. (Citation2021) classified motivations into five broader categories, a methodological choice that, while useful for high-level analysis, may overlook the context-specific details crucial for understanding the diverse drivers of illegal harvesting. This focus often neglects the intricate web of individual and community factors that play a significant role in shaping these motivations (Hübschle, Citation2017; Lunstrum & Givá, Citation2020). Specific characteristics of the study populations – such as age, gender, cultural practices, and socio-economic conditions can influence motivations and modus operandi (Abd Mutalib et al., Citation2013; Hübschle, Citation2017; Liu et al., Citation2011; Lowassa et al., Citation2012; Luskin et al., Citation2014) – delving into these characteristics is thus vital for contextualising motivations and designing targeted interventions. To gain a deeper understanding of what motivates people to illegally harvest wildlife, a more detailed and methodical analysis that goes beyond the conventional categorisations is required.

This scoping review builds on previous research by delving deeper into the methodologies used, offering another perspective on the documented motivations in existing studies. We aim to identify and explore knowledge gaps, add to the literature, and assess the methods used by previous studies. Additionally, it seeks to identify and examine the key characteristics and factors associated with the motivations behind illegal harvesting.

2. Materials and methods

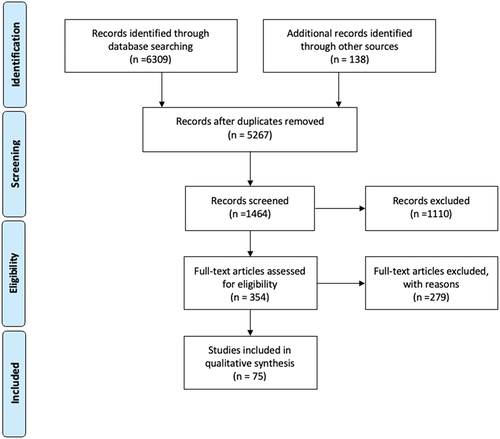

We developed a comprehensive and broad search strategy that covers both peer-reviewed and grey literature (including dissertations and theses). The protocol for this search strategy was pre-registered at the Open Science Framework (URL REMOVED FOR DOUBLE BLIND REVIEW). The Open Science Framework is a project tool that promotes open science, and best practices regarding reproducibility, transparency, and data management (Foster & Deardorff, Citation2017). We only included studies that incorporated first-hand data on illegal harvesting using interviews or surveys, excluding articles that merely discussed motivations of illegal harvesting or were obtained through interviews with other parties than the harvesters e.g. law enforcement. We defined illegal harvesting of wildlife as the harvest (taking or killing) of wildlife and their parts or derivatives in violation of local, national, or international legislation, yet excluding timber (wood or parts of tree used for construction or furniture). No date restrictions were placed on the searches or included studies, however, studies published after July 2020 were excluded as the search strategy was executed before that date. Following The Joanna Briggs Institute Manual for Scoping Reviews (Peters et al., Citation2015) and Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005), our search strategy was divided into three stages, initial search, primary search and documentation of the process and screening in a flowchart as proposed by Liberati et al. (Citation2009) ( and Appendix A in the Supplementary material).

2.1. Study selection

We removed duplicates and ineligible documents from the search results in Endnote X9 (The Endnote Team, Citation2013). Abstracts were screened using ASReview (van de Schoot et al., Citation2021), an active learning software for systematic reviews (http://www.asreview.nl). Within this software, the researcher interacts with the software documenting the researcher’s decisions (relevant vs irrelevant titles/abstracts). The model then iteratively updates its relevancy predictions for the remaining studies. By prioritising articles that are most likely to be relevant (i.e. certainty-based active learning) ASReview allows for the identification of 95% of relevant abstracts with the screening of approximately 20% of the publications (Ferdinands, Citation2021). We selected 12 relevant papers and 12 irrelevant papers as prior input knowledge and used the default Naïve Bayes active learning model. Each title and abstract were assessed by the primary researcher on eligibility and if the title or abstract mentioned motivations of illegal harvesting or any synonym of these terms. Screening continued until 100 consecutive abstracts were classified as irrelevant. A random subset of the obtained studies was screened by a second researcher and compared with results from the primary researcher to reduce risk of bias and calculate inter-rater reliability.

Inter-rater reliability was calculated with Cohen’s Kappa using the R package irr (Gamer et al., Citation2012). The probability rate was set at 0.248% classified as relevant by primary researcher). H0 was set at a Kappa of 0.6 as the upper limit of what would be unacceptably low. H1 was set at a Kappa of 0.81 as acceptable level of agreement. Initial analysis resulted in 87% agreement and Cohens Kappa of 0.5. Observed differences were discussed until agreement was obtained. This resulted in a 93% agreement and a Cohen’s Kappa of 0.75. Although slightly below the H1 threshold, further investigation revealed that the selection made by the primary researcher contained a larger number of studies. None of the studies included by the second researcher were excluded by the primary researcher. As this in the worst case would only increase the number of false positives that had to be screened out in the next stage, it was considered justified to include all documents identified as relevant for full-text screening. During full text screening, we evaluated each article based on our inclusion criteria (firsthand data through interviews or surveys, obtained with harvesters only) and documented motivations of illegal harvesting.

3.1. Data analysis

Studies selected for full-text screening were uploaded in the qualitative data analysis software NVIVO 12 (QSR International Pty Ltd., Citation2020). For each study, we coded the first time a motivation was mentioned in the text, geographical area, harvest methods, methodology used and taxa. For studies reporting data collection within more than one country, we regarded each country of data collection as a separate study as data collection methods may have differed.

Motivations were initially categorised based upon the classification obtained through a literature review for North America by Muth and Bowe (Citation1998). The authors classified the motivations for illegal harvesting in the literature into following motivations categories: (1) commercial gain, (2) household consumption, (3) recreational satisfactions, (4) trophy killing, (5) thrill killing, (6) protection of self and property, (7) poaching as rebellion, (8) poaching as a traditional right, (9) disagreement with specific regulations, and (10) gamesmanship. If studies documented motivations that did not fit these pre-defined categories, additional categories were added.

4. Results

Our comprehensive and broad search strategy resulted in 75 fully screened papers that met our inclusion criteria. Studies documented harvesting motivations for 1 – 4 countries per study, this resulted in a total of 82 studies in 46 countries on 6 continents ().

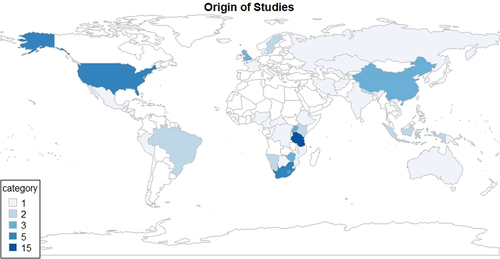

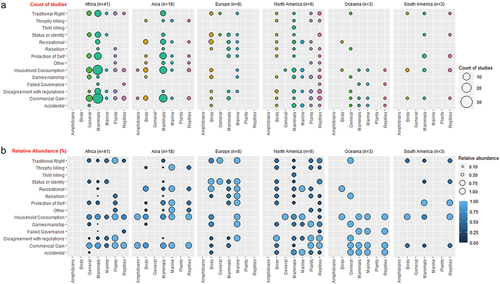

4.1. Geographic origin

Studies originating on the continent of Africa dominated the dataset with 41 of 82 studies (50%) conducted in Africa, followed by Asia (22%, n = 18), North America (11%, n = 9) and Europe (10%, n = 8). Both Oceania and South America accounted for, respectively, 4% (n = 3) each. The majority of countries were documented only once; Tanzania was the most frequently studied (n = 15).

4.2. Study characteristics

4.2.1. Sampling designs

Studies utilised relatively similar methods, with various levels of detail (Appendix B in the Supplementary material). Participants were selected using various sampling techniques, of which purposive sampling (n = 21) was the most frequently used, followed by snowball sampling (n = 20) and random sampling (n = 16). Other sampling techniques used were systematic (n = 7), stratified (n = 3), respondent-driven sampling (n = 4), and cluster sampling (n = 1). The remaining studies either used a mixed method approach (n = 2) or did not report their sampling method (n = 9).

4.2.2. Participant characteristics

Studies included on average 255 participants (range: 3–1811, SD = 340). Seven studies included known poachers in their study population, followed by known hunters (n = 15) and farmers (n = 4). Yet, most studies used a random population sample (n = 29) or mixed various types of participants (n = 27). Remaining data on participant characteristics was reported inconsistently. For instance, 44 studies (54%) did not provide any detail on the gender of the participants included. Ten studies consisted of all male participants, and in 28 studies men and women were both included. However, women only dominated the participants in two studies. Age of participants was reported in varying details. Fifty-seven studies (67%) did not report the age of participants, one study reported an average age, four studies reported merely a minimum age, and the remaining studies an age range. The ethnicity of participants was only reported by 14 studies, and participant religion only by one study.

4.2.3. Data collection methods

Data was obtained through a mix of several methods (n = 21), followed by semi- or structured interviews (n = 21), questionnaires (n = 3), group discussions (n = 2) and formal interviews (n = 1). One study did not state what method was used, and a further 32 merely mentioned the use of interviews. Ethical considerations regarding the study were reported by 37 studies. Only three studies specifically mentioned informed consent, and only four studies mentioned specific ethical guidelines in their methodology. A mere 34 studies reported relevant statistics, varying from frequencies of illegal harvest motivations to statistical models for hypotheses tested.

4.2.4. Harvested taxa

Of all studies, 13% (n = 12) did not disclose which taxa were illegally harvested. Studies included on average 1.29 taxonomic families (e.g. mammals, birds), and the highest number of taxonomic families included was four. Mammals were included in more than half of all studies (n = 54) and accounted for 60% of all taxonomic families mentioned. Followed by birds (n = 13) and reptiles (n = 11) Amphibians were the least included taxonomic family with only one study documenting illegal harvesting motivations for this taxon. Ungulates were most frequently documented with 24 studies (see Appendix B in the Supplementary material for specific species). However, often it remained unclear as to what taxa were included, with frequently a mere general description (n = 12). A total of 27 of 82 studies did not mention what taxa were studied other than higher-level taxonomy (e.g. mammals) or did not separate motivations for illegal harvesting.

4.3. Documented motivations

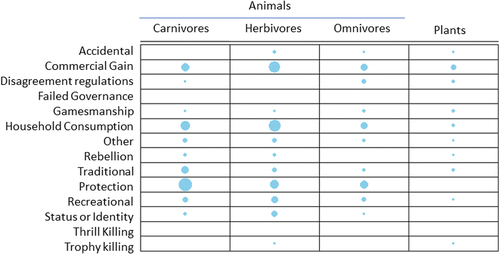

A total of 284 references to motivations were documented in the 82 studies, which we classified into 12 different motivation categories (, and Appendix B in the Supplementary material). The number of motivations mentioned per study ranged from 1 to 10, with on average 3.46 (SD = 1.90) motivations mentioned per study. Commercial gain was the most frequently mentioned motivation with 62 studies, accounting for 22% of all documented motivations, followed by Household consumption (n = 53, 19%), and Protection of self and/or property (n = 32, 11%). The least frequently mentioned motivation for illegal harvesting was Trophy killing (n = 3, 1.1%), followed by Thrill killing (n = 2, 0.7%). We added two additional motivation categories mentioned in the studies compared to Muth and Bowe (Citation1998), namely (11) Failed Governance and (12) Status and/or Identity.

Figure 3. Bubble chart showing the count of studies (top) divided by continent, taxa and documented motivation, and the relative abundance of motivations (bottom) divided by continent and taxa.

Table 1. Overview of documented motivations, descriptions, frequency of papers documenting that motivation and characteristic quotes for the specific motivations.

In addition, we documented miscellaneous motivations for which it was unclear as to what the actual motivation was for illegal harvesting. This group consisted of 5 motivations (4 studies), with varied statements of ‘being driven by evil spirits’, to ‘simply continuing after the harvest became illegal’, and ‘because it was easier than alternatives’. One study merely mentioned ‘Other’. In these cases, it was unclear as to what motivated the illegal harvesting of wildlife e.g. for household consumption or commercial gain, in the first place.

Motivations often seemed to overlap, and multiple motivations seemed to apply for the same harvesting incident. For instance, part of the meat harvested may be used for household consumption, while another part is used to gain income. None of the studies reported if they allowed multiple motivations to be recorded.

4.3.1. Commercial gain (references n = 62)

The illegal harvest of wildlife for commercial gain is aimed at obtaining an economic benefit. This can be derived from selling whole individual specimens, parts, or products, and in other cases people were paid to harvest specific species (Stiles, Citation2011). Some interviewees stated that selling harvested wildlife or wildlife products was used to purchase food (Loibooki et al., Citation2002; Lindsey and Parsel Project, 2009; Strong & Silva, Citation2020), clothes (Lubilo & Hebinck, Citation2019), other household needs, pay school fees of children (Harrison et al., Citation2015; P. A. Lindsey et al., Citation2011), pay for specific bills (Loibooki et al., Citation2002; Rytterstedt, Citation2016) or to pay for liquor (P. A. Lindsey et al., Citation2011; Lowassa et al., Citation2012). Interviewees that mentioned commercial gain were considered to be poor (De Greef, Citation2014), without jobs (Lubilo & Hebinck, Citation2019), had low monthly income, livestock ownership and/or food security (P. Lindsey, Citation2009) and pointed out that they had no alternative options (Harrison et al., Citation2015; O. P. Mmahi & Usman, Citation2019). However, one study pointed out that some made substantial profits (De Greef, Citation2014), while another study reported that interviewees simply liked the monetary return or even harvested illegally on a commercial scale (Rytterstedt, Citation2016). Several studies reported that households did not depend completely on the monetary gain of illegal harvesting, but this was often considered an activity to supplement other incomes (Hancock et al., Citation2017; Knapp et al., Citation2017; Mancini et al., Citation2011). Several studies quoted interviewees stating that they stopped harvesting illegally after they received alternative sources of income (De Greef, Citation2014; Lowassa et al., Citation2012; Lubilo & Hebinck, Citation2019; O. P. Mmahi & Usman, Citation2019), but that it does not make sense for skilled hunters to stop if no alternatives are available (Lubilo & Hebinck, Citation2019).

4.3.2. Household consumption (references n = 53)

Harvesting for household consumption was frequently intertwined with commercial gain, where part of the harvested meat was sold, and part used for consumption (Luskin et al., Citation2014; Ndibalema & Songorwa, Citation2008; Stirnemann et al., Citation2018). Twinamatsiko et al. (Citation2014) reported that the harvest for household consumption was not necessarily for food but could also be for medicinal purposes, construction materials, or fuelwood. Two studies stated that harvesting small amounts of meat for household subsistence was not considered wrong by interviewees (Bell et al., Citation2007; Eliason, Citation1999), but only if methods did not contravene a sense of fairness (Bell et al., Citation2007). In addition, Bell et al. (Citation2007) found that the harvest of non-edible species was frowned upon, and especially the killing of nursing female animals. Some interviewees stated that they harvested illegally to feed their family in times when they could not afford to buy meat, often aware of its illegality (Eliason, Citation1999, Citation2003; Forsyth et al., Citation1998; Lubilo & Hebinck, Citation2019). Illegally harvesting wildlife for household consumption was by some considered cheaper than other options (Rogan et al., Citation2018; J. L. van Velden et al., Citation2020), increased dietary diversity (Forsyth et al., Citation1998; J. L. van Velden et al., Citation2020), and was considered to be more readily available and easier to access (Pailler et al., Citation2009). Twinamatsiko et al. (Citation2014) found that the prohibition of harvesting natural resources for household consumption was considered the second main reason for a self-described low quality of life.

4.3.3. Protection of self and property (references n = 32)

Illegal harvest for the protection of self and property served to prevent livestock predation (Bashari et al., Citation2018; Bista et al., Citation2020; de Lima et al., Citation2020), crop raiding (Mwangi et al., Citation2016), to protect game species (Forsyth et al., Citation1998), or prevent the spread of diseases (Enticott, Citation2011) in addition to retaliatory killings of so-called ‘problem animals’ (Manqele, Citation2017; Strong & Silva, Citation2020). O. P. Mmahi and Usman (Citation2019) reported that vultures were killed as they were considered a nuisance to illegal harvesters alerting park rangers to where animals had been killed. Crop raiding and the subsequent loss of food was the most frequently mentioned reason for not having basic necessities and a low quality of life in the study by Twinamatsiko et al. (Citation2014). Retaliatory killings took place if people felt that they or their livelihood were in danger and appeared to be fuelled by the feeling that the impact of predators on their lives (Marchini & Macdonald, Citation2012), did not get enough support (Inskip et al., Citation2014) and insufficient compensation (Gayo et al., Citation2020). The perception that for instance a large predator could harm people or livestock in their village was enough for several interviewees to kill that animal (Gayo et al., Citation2020; Inskip et al., Citation2014).

4.3.4. Traditional right (references n = 28)

Illegal harvest motivated by a sense of traditional rights of access, or participation in a traditional activity, often those harvesting claim these activities have been unjustly prohibited. It appears to overlap with illegal harvest in disagreement with specific regulations like illegal hunting in specific parks (Mmahi & Usman, Citation2019). Interviewees stated that they possess traditional rights to the land and its resources (Lubilo & Hebinck, Citation2019; MacMillan & Han, Citation2011; Mancini et al., Citation2011), and they expect to be able to harvest these resources like in the past (Pokladnik, Citation2008), an activity that sometimes lasted for generations (Jenkins et al., Citation2017; Pokladnik, Citation2008). Forsyth et al. (Citation1998) reported that interviewees shared nostalgic memories of them harvesting wildlife when they were younger, or when harvesting was still legal (O. P. Mmahi & Usman, Citation2019). Harvesting was by some seen as a rite of passage, practiced by their ancestors, and integral part of their cultural repertoire (Knapp, Citation2012). This motivation also showed overlap with illegal harvesting for status or identity, as interviewees feared that with losing their tradition, they would lose their identity (Mischi, Citation2013).

4.3.5. Disagreement with specific regulations (references n = 21)

The illegal harvest of wildlife motivated by the disagreement with a specific legislation differs from harvesting motivated by rebellion as this category is targeted against a specific regulation instead of the government or state in general (Muth & Bowe, Citation1998). Disagreement with specific legislation overlapped with motivations regarding traditional rights to resources. Hübschle (Citation2017) found that displacement and dispossession were considered important factors for participation in illegal harvesting. Harrison et al. (Citation2015) found the resentment towards protected areas to be an important motivation for illegal harvesting. Interviewees stated that it was not fair that they were not allowed to harvest wildlife (Eliason, Citation2003; Madrigal-Ballestero & Jurado, Citation2017), without providing them with alternatives (O. P. Mmahi & Usman, Citation2019) or without equality in revenue sharing (Twinamatsiko et al., Citation2014). Cases of corruption (Twinamatsiko et al., Citation2014) or where banned products were still eaten by influential people (Forsyth et al., Citation1998), or confiscated products were given to friends and families of rangers (Madrigal-Ballestero & Jurado, Citation2017) were observed to further decrease compliance with these regulations. Interviewees stated that they hunted to protect their lifestyle and had the feeling that their point-of-view is not taking into consideration, which may further reduce the incentive for people to comply with harvesting bans (Rytterstedt, Citation2016).

4.3.6. Recreational (references n = 21)

The illegal harvest of wildlife for recreational purposes is driven by similar motives as the legal recreational harvest of wildlife (Muth & Bowe, Citation1998). Hunting trips were driven by the desire to experience satisfaction and for companionship among hunters. Interviewees stated that hunting was entertaining (Jenkins et al., Citation2017; MacMillan & Nguyen, Citation2014; Rytterstedt, Citation2016), and classified it as their hobby with the fresh meat as a bonus (Chang et al., Citation2017). Illegal hunting was perceived to be fun both on a personal (Chang et al., Citation2017) and community level (Chang et al., Citation2019), and some interviewees stated they liked it (MacMillan & Nguyen, Citation2014). The excitement of participating was important, but other interviewees also described it as relaxing, and ‘a way to maintain health’ (Jenkins et al., Citation2017).

4.3.7. Status or identity (references n = 20)

Illegal harvest for status or identity was often interlinked with other motivations like household consumption or traditional rights. Harvested wildlife was for instance used for entertaining guests or sharing with friends or family (Forsyth et al., Citation1998; Pailler et al., Citation2009). Interviewees stated that they felt ashamed if they did not have any meat to share (Bell et al., Citation2007). Bell et al. (Citation2007) found that sharing the harvested meat was seen as a celebration and symbols of solidarity and shared identity as hunters. Besides feeling ashamed for not being able to provide for family or friends, successful hunts could earn hunters respect from the community (Kaltenborn et al., Citation2005) or their partners (Lowassa et al., Citation2012). Hunting was perceived as a skill and being a good hunter could make the hunter feel proud of their skills. Successful hunters, and attainable wealth, were said by some to improve the social and economic status of hunters (Lunstrum & Givá, Citation2020), although this appeared to be a significant motivation for all interviewees (Travers et al., Citation2019). However, hunters were also pressured into illegal harvesting by others to fulfil their gender roles, whereby their masculinity was questioned if they were not harvesting (Lowassa et al., Citation2012). Yet, illegal harvesters often did not see themselves as poachers but referred to themselves for example as primarily fishermen or hunters (De Greef, Citation2014).

4.3.8. Gamesmanship (references n = 13)

The interactions between illegal harvesters and law enforcement often play out like a game, in which each is trying to outsmart the other (Muth & Bowe, Citation1998). This ‘game of cat and mouse’ appeared to be an important motive for many. Some interviewees stated that they wanted to see if they could get away with it (Bergseth et al., Citation2017), and often deployed tactics to avoid penalties (Chang et al., Citation2017; Forsyth et al., Citation1998; O. P. Mmahi & Usman, Citation2019). This included hiding guns or other attributes when confronted with law enforcement (1998). In one case, interviewees used spiritual powers to evade capture by turning invisible (O. P. Mmahi & Usman, Citation2019). Harvesters seemed to generally be aware of law enforcement and their movements, knowing exactly how to evade capture (Forsyth et al., Citation1998). The excitement and exhilaration of getting away from game wardens were the primary motivations for some to poach, stating that it was more fun to be an outlaw when game wardens are around than to hunt legally (Forsyth et al., Citation1998).

4.3.9. Rebellion (references n = 10)

This motivation is an act of rebellion primarily in revenge, in protest of environmental management, or the government in general (Muth & Bowe, Citation1998). Some interviewees stated they harvested illegally in protected areas as a form of protest in revenge after arrests were made by rangers, or in response to perceived wrongdoing by park authorities (Gandiwa, Citation2011). Other interviewees mentioned the inequality of revenue sharing and lack of employment (Gandiwa, Citation2011; Harrison et al., Citation2015) as reasons for illegal harvesting as a form of rebellion. Mischi (Citation2013) even documented a mass poaching event in which hundreds of people went hunting outside the hunting season as a political protest. Hunters leaned towards illegal harvesting as a way of expressing resistance (Peterson et al., Citation2019), primarily to protect a lifestyle that they perceived was being threatened (Rytterstedt, Citation2016).

4.3.10. Accidental (references n = 9)

Many interviewees denied responsibility for the illegal harvesting of wildlife, claiming it was a mistake or an accident, frequently stating that they do not hunt illegally or had no intention to harvest illegally. Reported mistakes or accidents included 1) not remembering a licence was required or having expired licences (Eliason, Citation2003), 2) forgetting to tag the animal (Eliason, Citation2003), 3) harvesting the wrong animal (Eliason, Citation1999), or 4) moving harvested wildlife before tagging the animal (Eliason, Citation2004). In addition, individuals reported that they harvested illegally because they were not aware of laws and regulation (Jenkins et al., Citation2017) or of the impact of illegal harvesting (Busilacchi et al., Citation2018).

4.3.11. Failed governance (references n = 5)

Failed Governance was mentioned as motivation for illegal harvesting of wildlife (Busilacchi et al., Citation2018). Studies cited issues of bribing (Busilacchi et al., Citation2018), lack of adequate law enforcement and surveillance (Pokladnik, Citation2008), and a general feeling that governments valued animals above people’s livelihoods (Hübschle, Citation2017).

4.3.12. Trophy killing (references n = 3)

The illegal harvesting of wildlife for the purpose of obtaining trophiesFootnote1 was only mentioned by three studies, where it was mentioned as one of the lowest rated motivations for illegal harvesting (Bashari et al., Citation2018; Eliason, Citation2004; Pokladnik, Citation2008). Trophy killing was only mentioned in relation to the shooting of big ungulates (Eliason, Citation2004) and plant harvesting (Pokladnik, Citation2008).

4.3.13. Thrill killing (references n = 2)

The illegal harvesting of wildlife for the thrill of it was only mentioned by two studies (Eliason, Citation2003; Forsyth et al., Citation1998). The main objective of harvesting for this motivation is the harvesting itself and the thrill obtained during the process rather than an economic of cultural purpose. In these cases, the product or animal harvested is often not utilised. Here it differs from Recreational where the desire to experience satisfaction, companionship among hunters or participating is the main drivers, and not the actual harvest itself.

4.4. Differences between taxa?

Different taxa can be harvested for different purposes, used as different products, and therefore supply different markets. In addition, not all taxa are as desirable as others, and thus impact people’s life and property differently. While most studies focused on multiple taxa, documented motivations were not always separated by taxa. The lack of data on exact taxa studied and the varying quality of studies did not allow for more advanced statistical analysis of motivational differences between taxa. However, we found some indications that certain motivations may differ between taxa. When all documented taxa were combined and divided by dietary type (), differences appeared to be visible between herbivores (8 taxa and ‘ungulates’) and carnivores (29 taxa). Protection of self and/or property was documented 24 times for carnivores, and merely 11 times for herbivores. For carnivores these motivations comprised primarily of retaliatory killings following, or in prevention of, loss of harvest, cattle, or human life (Manqele, Citation2017; Strong & Silva, Citation2020), while herbivores were for instance illegally harvested to prevent crop raiding (Mwangi et al., Citation2016). Illegal harvest for household consumption and or commercial gain was more frequently mentioned for herbivores (19 vs 12 and 18 vs 9). Although herbivores, and in particular ungulates, are overrepresented in this study’s dataset, there do seem to be some differences between herbivores and carnivores, suggesting that certain motivations might differ across dietary groups.

5. Discussion

5.1. Contribution to research aims

This study set out to address four key aims: 1) provide an overview of documented motivations in current research, 2) examine methodologies used to determine motivations, 3) identify key characteristics and factors related to motivations of illegal harvest, and 4) identify and analyse knowledge gaps regarding the motivations of illegal harvest. Firstly, we provided a multifaceted overview of twelve documented motivations. The found motivations are consistent with previous studies (Lavadinović et al., Citation2021; Lunstrum & Givá, Citation2020; J. van Velden et al., Citation2018), suggesting that socio-economic motivations like commercial gain or household consumption are among the most frequently mentioned motivations for the illegal harvest of wildlife. Consistent with previous reviews, we also find that different motivations are frequently interlinked (Lavadinović et al., Citation2021) and multiple motivations can play a role in the same harvesting incident. The complexity of what motivates someone to illegally harvest wildlife has been highlighted in the past (Lavadinović et al., Citation2021; Lunstrum & Givá, Citation2020; Montgomery, Citation2020; Von Essen et al., Citation2014). More recently, Montgomery (Citation2020) pointed out that motives often contain numerous subcategories which frequently overlap.

According to Lunstrum and Givá (Citation2020), despite economic factors being the most important drivers of rhino poaching, it is better captured in the more complex concept of economic inequality. Lunstrum and Givá (Citation2020) argued that the economic motivations driving illegal wildlife harvesting are multifaceted, ranging from material deprivation and caring for others to more self-interested drivers. Caution is thus necessary to ensure that the complexity of what motivates someone to illegally harvest wildlife is not lost by over-simplifying the classification, our study included. It is critical to accurately portray the complexities of what motivates people to illegally harvest wildlife to shape appropriate responses. In addition, the frequency of motivations mentioned in the literature does not necessarily reflect the frequency or relative importance of these motivations playing a role in reality, as this can be influenced by study design (e.g. focus on supply-side drivers vs demand-side drivers).

Secondly, by examining varied methodologies, our findings suggest that, considering the difficulties and limitations of studying illegal harvesting, the literature on motivations for illegal wildlife harvest is geographically and taxonomically biased. Furthermore, data collection is irregular, and important factors are not always collected. This also significantly hampered our aim to identify key characteristics and factors contributing to illegal harvesting. Lastly, we provide several knowledge gaps and propose potential avenues for future research. Our contribution confirms the findings from past reviews (e.g. Lavadinović et al., Citation2021) but expands on this by looking into detail about the reported methodologies and study characteristics. Additionally, we tried to add more context to the motivations found in this study by expanding on the species for which these were reported.

5.2. Motivations vs. rationalizations

It is crucial to differentiate between motivations that lead to illegal harvesting and rationalisations that occur post hoc. It is unclear to what extent this was the case in our dataset, and thus to what extent this was inadvertently masking what is really motivating the harvest. Since most studies were cross-sectional or qualitative in nature, motivations provided by hunters may also be considered neutralisation techniques, a criminological concept that seeks to classify the discourses by which individuals seek to justify and rationalise rule-breaking behaviour (e.g. Coleman, Citation2001; Sykes & Matza, Citation1957). For instance, in studies that included the motivational category Traditional rights, interviewees justified the harvesting behaviour with claims of entitlement, but the harvest itself might have been motivated by obtaining meat for household consumption. The motivational category Accidental is arguably a post hoc rationalisation of harvesting behaviour (denial of responsibilities), because it does not explain the underlying motivation of why interviewees were harvesting in the first place. Failed governance can also be seen as a lack of deterrents, wherein the ineffectiveness of monitoring and enforcement leads to perceptions among harvesters that the probability of getting caught is relatively low (Madrigal-Ballestero & Jurado, Citation2017). Although several of the observed motivational categories are often referenced in the literature as motivations, and we have therefore described them as such, we argue that these are more likely rationalisations. While some studies indeed recognised this (Eliason, Citation2003, Citation2004; Enticott, Citation2011; Rytterstedt, Citation2016) and highlighted that they documented neutralisation techniques, other studies did not. Rationalisations can help offenders to overcome the barrier to illegal harvest, but also rationalise the illegal harvest afterwards (Sykes & Matza, Citation1957). To facilitate a better understanding of what motivates people to illegally harvest wildlife, future studies should differentiate between the motivation and rationalisation of the reported behaviour.

5.3. Methodological reflections

While our methodology has its strengths, it also poses limitations. Our choice to limit the dataset to literature in the English language excluded all available literature in other languages, which likely resulted in several relevant studies being excluded. In addition, we aimed for studies that had incorporated first-hand data, obtained from harvesters, on illegal harvesting and excluded second-hand information or studies that merely evaluated the negative conservation impact of illegal wildlife harvest. However, this also allowed us to overcome issues observed by Lavadinović et al. (Citation2021), where many studies did not report what motivated people to illegally harvest but merely discussed the negative conservation impact. Here, we focus solely on studies describing harvest which is deemed illegal by law in the study location, yet this does not necessarily mean that this harvest has a negative conservation impact. Harvest can be illegal by law but done in a sustainable matter, even including critically endangered species (Nijman, Citation2022), and legal harvest can be done at levels that have a negative conservation impact.

5.4. Addressing research biases

Our research highlighted significant geographical and taxonomical biases. These biases have most likely shaped our understanding of what motivates people to illegally harvest wildlife.

Research into motivations of illegal wildlife harvesting was spatially biased towards the African region, and in particular the country of Tanzania. Lavadinović et al. (Citation2021) reported similar findings, wherein Africa was the main location for illegal harvesting studies and argued that this bias might be explained by the intensity of harvesting and trafficking in this region. Lavadinović and colleagues also argued that research interest, colonial context, and postcolonial discourse of nature conservation are likely to underpin geographical biases in illegal harvesting studies, similar to other studies (Singh & Van Houtum, Citation2002). Research interest, and the ability to obtain funding for data collection are also likely to be influenced by how charismatic a species is considered (Bellon, Citation2019; Courchamp et al., Citation2018; Lavadinović et al., Citation2021). In our case, the presence of the world-famous Serengeti ecosystem in Tanzania might increase research interests for this area and thus influence the overrepresentation of Tanzania in our review.

Studies focusing on mammals are significantly overrepresented in the literature. Our search parameters for instance only resulted in one study that included motivations for illegal harvesting of amphibians (Scheffers et al., Citation2012), whereas illegal harvesting of amphibians has been widely documented (Auliya, García-Moreno, et al., Citation2016; de Magalhães & São-Pedro, Citation2012; De Paula et al., Citation2012; Pistoni & Toledo, Citation2010). Lavadinović et al. (Citation2021), which, despite finding a weak correlation between species and motivations, and as a result did not discuss this further. We aimed to expand on this, and our data suggest that the motivations to illegally harvest are likely to be taxa-specific and seem to relate to the dietary type of studied taxa. However, due to the quality of the data we could not explore this further. Separating motivations by taxa and exploring differences in motivations between taxa could provide an additional layer of understanding of harvesting motivations. Different taxa can be used for different products, which supply different markets, and thus it is important to be ‘crime specific’ when studying illegal harvest motivations (Connealy, Citation2020). Carnivorous taxa, like wolves or lions, targeting livestock are more likely to be harvested for protection motives instead of human consumption. In contrast to the sample of studies used by Lavadinović et al. (Citation2021), our samples of studies were not biased towards charismatic species like elephants, rhinos, and wolves, although all three were documented in the dataset (Appendix B in the Supplementary material), Instead, ungulates were the main taxa mentioned in the studies included in our review. This was primarily due to the inclusion criteria of studies utilising interviews or surveys, resulting in many supply-side studies with for instance bushmeat hunters, which is often prohibited in reserves and parks.

5.5. Data collection and reporting standards

The variability in data collection and reporting observed in this field affects the reliability of motivations’ interpretation. The level of detail to which the methodology was reported was observed to be irregular and frequently did not include important factors able to explain the observed motivations. Although the complexity of these harvesting motivations has been reported throughout time (e.g. Hübschle, Citation2017; Kahler and Gore, Citation2012; Kühl et al., Citation2009; Muth & Bowe, Citation1998), a more advanced analysis to gain a deeper understanding of which key factors determine these motivations is significantly hindered by the irregular and infrequent reporting of these factors. Previous studies have for instance shown that men and women can play different roles in illegal harvesting of wildlife (Lowassa et al., Citation2012; Seager, Citation2021), and thus including gender is necessary to provide an additional layer of understanding about motivations and roles in illegal harvesting. Documenting the age of participants is important to increase understanding of who is harvesting and why. Several studies documented that young men were primarily involved in illegally harvesting wildlife, who were frequently encouraged by older and more experienced men (Lunstrum & Givá, Citation2020). Certain ethnicities have been documented to be involved in illegal harvesting in certain regions (Liu et al., Citation2011), and to use specific methods for harvesting, which often stemmed from religious beliefs among ethnic groups (Abd Mutalib et al., Citation2013; Luskin et al., Citation2014; Macrae & Whiting, Citation2014). Yet only one study (Luskin et al., Citation2014) documented the religion of interviewees. This study found that interviewed Muslims avoided the harvesting of wild boar (Sus scrofa) for religious reasons, but that this species was harvested by people with other religions.

Despite criticising the methodologies used by the studies in this review, we recognise the difficulties and limitations of studying illicit behaviour like illegal wildlife harvesting and applaud the authors of the papers under review for their valuable work to tackle some of these difficulties. We realise that the ideal methodology might often not be feasible, however, to enhance research quality, studies should still strive to reach this within existing constraints to see if a form of generalisation is possible.

5.6. The need for universal definitions

The absence of a universal definition of this type of wildlife crime (UNODC, Citation2016) further complicates the interpretation of motivations and prevents a deeper understanding. Some relate illegal harvesting to property rights and norms (Gombay, Citation2014), whereas others include any non-authorised hunting (Rizzolo et al., Citation2017). Other studies approach illegal harvesting by categorising the crime (Forsyth & Marckese, Citation1993; Forsyth et al., Citation1998; Muth & Bowe, Citation1998), profiling the perpetrator (Bell et al., Citation2007; Eliason, Citation2004), or simply considering it to be an environmental or conservation concern (Boakye et al., Citation2016; Everatt et al., Citation2015, Citation2019; Herbig & Minnaar, Citation2019). This lack of a universal definition poses a significant challenge to the comparability of studies in any systematic or scoping review. Without a consistent framework for what constitutes wildlife crime, studies may vary in their scope and methodology, leading to heterogeneity that complicates the synthesis of findings and undermines the ability to draw generalisable conclusions. This lack of standardisation can result in discrepancies in data collection, analysis, and interpretation, making it difficult to assess the prevalence, patterns, and motivations of illegal harvesting across different studies. Consequently, the development of a comprehensive and universally accepted definition is crucial to ensure that research in this field can be reliably compared and integrated, providing a clearer picture of the global situation and informing the creation of more effective policies and interventions.

5.7. Societal implications and recommendations for practice

Our scoping review of illegal harvesting motivations has clear societal implications. These findings highlight the urgent need for detailed, context-sensitive data collection. The motivations we identified emphasise the importance of creating prevention strategies that are as varied and nuanced as the contexts they aim to address. Crucially, these strategies must be rooted in a deep understanding of the localised socio-economic and cultural contexts that shape illegal harvesting behaviours (Rizzolo et al., Citation2017). Thereby aligning conservation efforts with community support, and reduced livelihood impacts diminishing the appeal of illegal harvesting, and promoting a collective guardianship of the environment.

6. Conclusion

Our findings suggest that, although considering the difficulties and limitations of studying illegal harvesting, the literature on motivations for illegal wildlife harvest is geographically and taxonomically biased, and that data collection is irregular and important factors are not always collected. What motivates someone to illegally harvest wildlife has been shown to be a complex issue, yet the necessary data to place findings in appropriate context are frequently thus not collected or reported. These methodological choices shape our understanding of these motivations, the key characteristics involved, and which knowledge gaps remain. Future research must go beyond a general description while allowing for context-specific adjustments and should aim to overcome geographic biases, as well as taxonomic biases by examining a broader range of taxa, while striving for the most complete methodology.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Excel (12.7 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Excel (52.5 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/17440572.2024.2342780.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Trophy killing here differs from the legal trophy/sports hunting by that harvesting in the context of this manuscript is considered illegal by law.

References

- Abd Mutalib, A. H., Fadzly, N., & Foo, R. (2013). Striking a balance between tradition and conservation: General perceptions and awareness level of local citizens regarding turtle conservation efforts based on age factors and gender. Ocean & Coastal Management, 78, 56–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2013.03.015

- Abi-Said, M. R., Outa, N. T., Makhlouf, H., Amr, Z. S., & Eid, E. (2018). Illegal trade in wildlife species in Beirut, Lebanon. Vertebrate Zoology, 68(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.3897/vz.68.e32214

- Alves, R. R. N., Rosa, I. L., Albuquerque, U. P., & Cunningham, A. B. (2013). Medicine from the wild: An overview of the use and trade of animal products in traditional medicines. In R. R. N. Alves & I. L. Rosa (Eds.), Animals in traditional folk medicine (pp. 25–42). Springer-Verlag.

- Anagnostou, M., & Doberstein, B. (2022). Illegal wildlife trade and other organised crime: A scoping review. AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment, 51(7), 1615–1631. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-021-01675-y

- Arias, A., Cinner, J. E., Jones, R. E., & Pressey, R. L. (2015). Levels and drivers of fishers’ compliance with marine protected areas. Ecology and Society, 20(4), 19. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-07999-200419

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Auliya, M., Altherr, S., Ariano-Sanchez, D., Baard, E. H., Brown, C., Brown, R. M., Cantu, J.-C., Gentile, G., Gildenhuys, P., Henningheim, E., Hintzmann, J., Kanari, K., Krvavac, M., Lettink,M., Lippert, J., Luiselli, L., Nilson, G., Nguyen, T. Q., Nijman, V., … Ziegler, T. (2016). Trade in live reptiles, its impact on wild populations, and the role of the European market. Biological Conservation, 204, 103–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2016.05.017

- Auliya, M., García-Moreno, J., Schmidt, B. R., Schmeller, D. S., Hoogmoed, M. S., Fisher, M. C., Pasmans, F., Henle, K., Bickford, D., & Martel, A. (2016). The global amphibian trade flows through Europe: The need for enforcing and improving legislation. Biodiversity and Conservation, 25(13), 2581–2595. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-016-1193-8

- Bashari, M., Sills, E., Peterson, M. N., & Cubbage, F. (2018). Hunting in Afghanistan: Variation in motivations across species. Oryx, 52(3), 526–536.

- Bell, S., Hampshire, K., & Topalidou, S. (2007). The political culture of poaching: A case study from northern Greece. Biodiversity and Conservation, 16(2), 399–418. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-005-3371-y

- Bellon, A. M. (2019). Does animal charisma influence conservation funding for vertebrate species under the US endangered species act? Environmental Economics and Policy Studies, 21(3), 399–411. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10018-018-00235-1

- Bergseth, B. J., Williamson, D. H., Russ, G. R., Sutton, S. G., & Cinner, J. E. (2017). A social–ecological approach to assessing and managing poaching by recreational fishers. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 15(2), 67–73. https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.1457

- Bista, D., Baxter, G. S., & Murray, P. J. (2020). What is driving the increased demand for red panda pelts? Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 25(4), 324–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871209.2020.1728788

- Boakye, M. K., Kotzé, A., Dalton, D. L., & Jansen, R. (2016). Unravelling the pangolin bushmeat commodity chain and the extent of trade in Ghana. Human Ecology, 44(2), 257–264. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-016-9813-1

- Brack, D. (2003). Illegal logging and the illegal trade in forest and timber products. International Forestry Review, 5(3), 195–198. https://doi.org/10.1505/IFOR.5.3.195.19148

- Busilacchi, S., Butler, J. R. A., Rochester, W. A., & Posu, J. (2018). Drivers of illegal livelihoods in remote transboundary regions: The case of the trans-fly region of papua New Guinea. Ecology and Society, 23(1). https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-09817-230146

- Chang, C. H., Barnes, M. L., Frye, M., Zhang, M., Quan, R.-C., Reisman, L. M. G., Levin, S. A., & Wilcove, D. S. (2017). The pleasure of pursuit; recreational hunters in rural Southwest China exhibit low exit rates in response to declining catch. Ecology and Society, 22(1). https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-09072-220143

- Chang, C. H., Williams, S. J., Zhang, M., Levin, S. A., Wilcove, D. S., & Quan, R.-C. (2019). Perceived entertainment and recreational value motivate illegal hunting in Southwest China. Biological Conservation, 234, 100–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2019.03.004

- Coleman, J. W. (2001). The criminal elite: The sociology of white collar crime. Macmillan.

- Connealy, N. T. (2020). Can we trust crime predictors and crime categories? Expansions on the potential problem of generalization. Applied Spatial Analysis and Policy, 13(3), 669–692. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12061-019-09323-5

- Courchamp, F., Jaric, I., Albert, C., Meinard, Y., Ripple, W. J., & Chapron, G. (2018). The paradoxical extinction of the most charismatic animals. PLOS Biology, 16(4), e2003997. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.2003997

- De Greef, K. (2014). Booming illegal abalone fishery in Hangberg: Tough lessons for small-scale fisheries governance in South Africa. University of Cape Town, Faculty of Science, Department of Biological Sciences. http://hdl.handle.net/11427/9187

- de Lima, N. D. S., Napiwoski, S. J., & Oliveira, M. A. (2020). Human-wildlife conflict in the southwestern amazon: Poaching and its motivations. Nature Conservation Research, 5(1), 109–114. https://doi.org/10.24189/ncr.2020.006

- de Magalhães, A. L. B., & São-Pedro, V. A. (2012). Illegal trade on non-native amphibians and reptiles in southeast Brazil: The status of e-commerce. Phyllomedusa: Journal of Herpetology, 11(2), 155–160. https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.2316-9079.v11i2p155-160

- De Paula, C. D., Pacífico-Assis, E. C., & Catão-Dias, J. L. (2012). Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis in amphibians confiscated from illegal wildlife trade and used in an ex situ breeding program in Brazil. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 98(2), 171–175. https://doi.org/10.3354/dao02426

- Duffy, R. (2016). War, by conservation. Geoforum, 69, 238–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.09.014

- Duffy, R., & St John, F. (2013). Poverty, poaching and trafficking: What are the links? Evidence on Demand.

- Duffy, R., St John, F. A. V., Büscher, B., & Brockington, D. (2016). Toward a new understanding of the links between poverty and illegal wildlife hunting. Conservation Biology, 30(1), 14–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12622

- Eliason, S. L. (1999). The illegal taking of wildlife: Toward a theoretical understanding of poaching. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 4(2), 27–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871209909359149

- Eliason, S. L. (2003). Illegal hunting and angling: The neutralization of wildlife law violations. Society and Animals, 11(3), 225–243. https://doi.org/10.1163/156853003322773032

- Eliason, S. L. (2004). Accounts of wildlife law violators: Motivations and rationalizations. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 9(2), 119–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871200490441775

- Eliason, S. L. (2012). From the King’s deer to a capitalist commodity: A social historical analysis of the poaching law. International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice, 36(2), 133–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/01924036.2012.669912

- The Endnote Team. (2013). EndNote. Philidelphia, PA: Clarivate.

- Enticott, G. (2011). Techniques of neutralising wildlife crime in rural England and Wales. Journal of Rural Studies, 27(2), 200–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2011.01.005

- Everatt, K. T., Andresen, L., & Somers, M. J. (2015). The influence of prey, pastoralism and poaching on the hierarchical use of habitat by an apex predator. South African Journal of Wildlife Research, 45(2), 187–196. https://doi.org/10.3957/056.045.0187

- Everatt, K. T., Kokes, R., & Lopez Pereira, C. (2019). Evidence of a further emerging threat to lion conservation; targeted poaching for body parts. Biodiversity and Conservation, 28(14), 4099–4114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-019-01866-w

- Ferdinands, G. (2021). AI-assisted systematic reviewing: Selecting studies to compare bayesian versus frequentist SEM for small sample sizes. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 56(1), 153–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2020.1853501

- Forsyth, C. J., Gramling, R., & Wooddell, G. (1998). The game of poaching: Folk crimes in southwest Louisiana. Society & Natural Resources, 11(1), 25–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941929809381059

- Forsyth, C. J., & Marckese, T. A. (1993). Thrills and skills: A sociological analysis of poaching. Deviant Behavior, 14(2), 157–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.1993.9967935

- Foster, E. D., & Deardorff, A. (2017). Open science framework (OSF). Journal of the Medical Library Association: JMLA, 105(2), 203–206. https://doi.org/10.5195/jmla.2017.88

- Gamer, M., Lemon, J., Gamer, M. M., Robinson, A., & Kendall’s, W. (2012). Package ‘irr’. Various coefficients of interrater reliability and agreement, 22.

- Gandiwa, E. (2011). Preliminary assessment of illegal hunting by communities adjacent to the Northern Gonarezhou National Park, Zimbabwe. Tropical Conservation Science, 4(4), 445–467. https://doi.org/10.1177/194008291100400407

- Gayo, L., Nahonyo, C. L., & Masao, C. A. (2020). Socioeconomic factors influencing local community perceptions towards lion conservation: A case of the selous game reserve, Tanzania. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 56(3), 480–494. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021909620929382

- Gombay, N. (2014). ‘Poaching’ – What’s in a name? Debates about law, property, and protection in the context of settler colonialism. Geoforum, 55, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2014.04.010

- Hancock, J. M., Furtado, S., Merino, S., Godley, B. J., & Nuno, A. (2017). Exploring drivers and deterrents of the illegal consumption and trade of marine turtle products in Cape Verde, and implications for conservation planning. Oryx, 51(3), 428–436. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605316000107

- Harrison, M., Baker, J., Twinamatsiko, M., & Milner-Gulland, E. J. (2015). Profiling unauthorized natural resource users for better targeting of conservation interventions. Conservation Biology, 29(6), 1636–1646. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12575

- Herbig, F., & Minnaar, A. (2019). Pachyderm poaching in Africa: Interpreting emerging trends and transitions. Crime, Law and Social Change, 71(1), 67–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-018-9789-4

- Hope, R. A. (2002). Wildlife harvesting, conservation and poverty: The economics of olive ridley egg exploitation. Environmental Conservation, 29(3), 375–384. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892902000255

- Hübschle, A. M. (2017). The social economy of rhino poaching: Of economic freedom fighters, professional hunters and marginalized local people. Current Sociology, 65(3), 427–447. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392116673210

- Huxley, C. (2000). CITES: The vision. In J. Hutton & B. Dickson (Eds.), Endangered species. Threatened convention, the past, present, and future of CITES (pp. 3–12). Earthscan Publications Ltd.

- Inskip, C., Fahad, Z., Tully, R., Roberts, T., & MacMillan, D. (2014). Understanding carnivore killing behaviour: Exploring the motivations for tiger killing in the Sundarbans, Bangladesh. Biological Conservation, 180, 42–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2014.09.028

- Janssen, J., & Leupen, B. T. (2019). Traded under the radar: Poor documentation of trade in nationally-protected non-CITES species can cause fraudulent trade to go undetected. Biodiversity and Conservation, 28(11), 2797–2804. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-019-01796-7

- Jenkins, H. M., Mammides, C., & Keane, A. (2017). Exploring differences in stakeholders’ perceptions of illegal bird trapping in Cyprus. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-017-0194-3

- Kahler, J. S., & Gore, M. L. (2012). Beyond the cooking pot and pocket book: Factors influencing noncompliance with wildlife poaching rules. International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice, 36(2), 103–120.

- Kaltenborn, B. P., Nyahongo, J. W., & Tingstad, K. M. (2005). The nature of hunting around the Western Corridor of Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. European Journal of Wildlife Research, 51(4), 213–222. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-005-0109-9

- Knapp, E. J. (2012). Why poaching pays: A summary of risks and benefits illegal hunters face in Western Serengeti, Tanzania. Tropical Conservation Science, 5(4), 434–445. https://doi.org/10.1177/194008291200500403

- Knapp, E. J., Peace, N., & Bechtel, L. (2017). Poachers and poverty: Assessing objective and subjective measures of poverty among illegal hunters outside Ruaha National Park, Tanzania. Conservation and Society, 15(1), 24–32. https://doi.org/10.4103/0972-4923.201393

- Kühl, A., Balinova, N., Bykova, E., Arylov, Y. N., Esipov, A., Lushchekina, A. A., & Milner-Gulland, E. J. (2009). The role of saiga poaching in rural communities: Linkages between attitudes, socio-economic circumstances and behaviour. Biological Conservation, 142(7), 1442–1449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2009.02.009

- Lavadinović, V. M., Islas, C. A., Chatakonda, M. K., Marković, N., & Mbiba, M. (2021). Mapping the research landscape on poaching: A decadal systematic review. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 9, 177. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2021.630990

- Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gøtzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P. A., Clarke, M., Devereaux, P. J., Kleijnen, J., & Moher, D. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 62(10), e1–e34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006

- Lindsey, P. (2009). The illegal meat trade affecting wildlife based land use in the south east lowveld of Zimbabwe: Drivers, impacts, and potential solutions. PARSEL Project.

- Lindsey, P. A., Romañach, S. S., Matema, S., Matema, C., Mupamhadzi, I., & Muvengwi, J. (2011). Dynamics and underlying causes of illegal bushmeat trade in Zimbabwe. Oryx, 45(1), 84–95. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605310001274

- Liu, F., McShea, W. J., Garshelis, D. L., Zhu, X., Wang, D., & Shao, L. (2011). Human-wildlife conflicts influence attitudes but not necessarily behaviors: Factors driving the poaching of bears in China. Biological Conservation, 144(1), 538–547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2010.10.009

- Loibooki, M., Hofer, H., Campbell, K. L. I., & East, M. L. (2002). Bushmeat hunting by communities adjacent to the Serengeti National Park, Tanzania: The importance of livestock ownership and alternative sources of protein and income. Environmental Conservation, 29(3), 391–398. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892902000279

- Lowassa, A., Tadie, D., & Fischer, A. (2012). On the role of women in bushmeat hunting – Insights from Tanzania and Ethiopia. Journal of Rural Studies, 28(4), 622–630. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2012.06.002

- Lubilo, R., & Hebinck, P. (2019). ‘Local hunting’ and community-based natural resource management in Namibia: Contestations and livelihoods. Geoforum, 101, 62–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.02.020

- Lunstrum, E., & Givá, N. (2020). What drives commercial poaching? From poverty to economic inequality. Biological Conservation, 245, 108505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108505

- Luskin, M. S., Christina, E. D., Kelley, L. C., & Potts, M. D. (2014). Modern hunting practices and wild meat trade in the oil palm plantation-dominated landscapes of Sumatra, Indonesia. Human Ecology, 42(1), 35–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-013-9606-8

- MacMillan, D. C., & Han, J. (2011). Cetacean by-catch in the Korean Peninsula—By chance or by design? Human Ecology, 39(6), 757–768. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-011-9429-4

- MacMillan, D. C., & Nguyen, Q. A. (2014). Factors influencing the illegal harvest of wildlife by trapping and snaring among the Katu ethnic group in Vietnam. Oryx, 48(2), 304–312. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605312001445

- Macrae, I., & Whiting, S. (2014). Positive conservation outcome from religious teachings: Changes to subsistence turtle harvest practices at Cocos (Keeling) Islands, Indian Ocean. Raffles Bulletin of Zoology, 162–167.

- Madrigal-Ballestero, R., & Jurado, D. (2017). Economic incentives, perceptions and compliance with marine turtle egg harvesting regulation in Nicaragua. Conservation and Society, 15(1), 74–86. https://doi.org/10.4103/0972-4923.201392

- Mancini, A., Senko, J., Borquez-Reyes, R., Póo, J. G., Seminoff, J. A., & Koch, V. (2011). To poach or not to poach an endangered species: Elucidating the economic and social drivers behind illegal sea turtle hunting in Baja California Sur, Mexico. Human Ecology, 39(6), 743–756. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-011-9425-8

- Manqele, N. S. (2017). Assessing the drivers and impact of illegal hunting for bushmeat and trade on serval (Leptailurus serval, Schreber 1776) and Oribi (Ourebia ourebi, Zimmermann 1783) in South Africa [ Thesis]. Retrieved January 27, 2021, from https://researchspace.ukzn.ac.za/handle/10413/16283

- Marchini, S., & Macdonald, D. W. (2012). Predicting ranchers’ intention to kill jaguars: Case studies in Amazonia and pantanal. Biological Conservation, 147(1), 213–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2012.01.002

- Mischi, J. (2013). Contested rural activities: Class, politics and shooting in the French countryside. Ethnography, 14(1), 64–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/1466138112440980

- Mmahi, O. P., & Usman, A. (2019). “Hunting is our heritage; we commit no offence”: Kainji National Park Wildlife Poachers, Kaiama, Kwara State Nigeria. Deviant Behavior, 12(41), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2019.1629537.

- Montgomery, R. A. (2020). Poaching is not one big thing. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 35(6), 472–475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2020.02.013

- Muth, R. M., & Bowe, J. F. J. (1998). Illegal harvest of renewable natural resources in North America: Toward a typology of the motivations for poaching. Society and Natural Resources, 11(1), 9–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941929809381058

- Mwangi, D. K., Akinyi, M., Maloba, F., Ngotho, M., Kagira, S., Maloba, F., Kivai, J., & Ndeereh, D. (2016). Socioeconomic and health implications of human—wildlife interactions in Nthongoni, Eastern Kenya. African Journal of Wildlife Research, 46(2), 87–102. https://doi.org/10.3957/056.046.0087

- Ndibalema, V. G., & Songorwa, A. N. (2008). Illegal meat hunting in serengeti: Dynamics in consumption and preferences. African Journal of Ecology, 46(3), 311–319. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2028.2007.00836.x

- Nijman, V. (2022). Harvest quotas, free markets and the sustainable trade in pythons. Nature Conservation, 48, 99–121. https://doi.org/10.3897/natureconservation.48.80988

- Nijman, V., & Nekaris, K. A. I. (2014). Trade in wildlife for medicinal and decorative purposes in Bali, Indonesia. TRAFFIC Bulletin, 26(1), 31–36.

- Pailler, S., Wagner, J. E., McPeak, J. G., & Floyd, D. W. (2009). Identifying conservation opportunities among Malinké bushmeat hunters of Guinea, West Africa. Human Ecology, 37(6), 761–774. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-009-9277-7

- Peters, M., Godfrey, C., McInerney, P., Soares, C., Khalil, H., & Parker, D. (2015). The Joanna Briggs Institute reviewers’ manual 2015: Methodology for JBI scoping reviews. The Joanna Briggs Institute.

- Peterson, M. N., von Essen, E., Hansen, H. P., & Peterson, T. R. (2019). Shoot shovel and sanction yourself: Self-policing as a response to wolf poaching among Swedish hunters. AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment, 48(3), 230–239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-018-1072-5

- Pistoni, J., & Toledo, L. F. (2010). Amphibian illegal trade in Brazil: What do we know? South American Journal of Herpetology, 5(1), 51–56. https://doi.org/10.2994/057.005.0106

- Plumptre, A. J., Bizumuremyi, J.-B., Uwimana, F., & Ndaruhebeye, J.-D. (1997). The effects of the Rwandan civil war on poaching of ungulates in the Parc National des Volcans. Oryx, 31(4), 265–273. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3008.1997.d01-15.x

- Pokladnik, R. J. (2008). Roots and remedies of ginseng poaching in Central Appalachia [ Doctoral dissertation]. Antioch University.

- QSR International Pty Ltd. (2020). NVivo (released in 2020).

- Rija, A. A., Critchlow, R., Thomas, C. D., Beale, C. M., & Grignolio, S. (2020). Global extent and drivers of mammal population declines in protected areas under illegal hunting pressure. PLOS ONE, 15(8), e0227163. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0227163

- Rizzolo, J. B., Gore, M. L., Ratsimbazafy, J. H., & Rajaonson, A. (2017). Cultural influences on attitudes about the causes and consequences of wildlife poaching. Crime, Law and Social Change, 67(4), 415–437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-016-9665-z

- Rogan, M. S., Miller, J. R., Lindsey, P. A., & McNutt, J. W. (2018). Socioeconomic drivers of illegal bushmeat hunting in a southern African Savanna. Biological Conservation, 226, 24–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2018.07.019

- Rytterstedt, E. (2016). ‘I don’t see myself as a criminal’: Motivation and neutralization of illegal hunting by Swedish Norrland Hunters. In G. R. Potter, A. Nurse, & M. Hall (Eds.), The geography of environmental crime (pp. 217–239). Palgrave Macmilan.

- Scheffers, B. R., Corlett, R. T., Diesmos, A., & Laurance, W. F. (2012). Local demand drives a bushmeat industry in a Philippine forest preserve. Tropical Conservation Science, 5(2), 133–141. https://doi.org/10.1177/194008291200500203

- Seager, J. (2021). Gender and illegal wildlife trade: Overlooked and underestimated. WWF.

- Singh, J., & Van Houtum, H. (2002). Post-colonial nature conservation in Southern Africa: Same emperors, new clothes? Geo Journal, 58(4), 253–263. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:GEJO.0000017956.82651.41

- Stiles, D. (2011). Elephant meat and ivory trade in central Africa. Pachyderm, 50, 26–36.

- Stirnemann, R. L., Stirnemann, I. A., Abbot, D., Biggs, D., & Heinsohn, R. (2018). Interactive impacts of by-catch take and elite consumption of illegal wildlife. Biodiversity and Conservation, 27(4), 931–946. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-017-1473-y

- Strong, M., & Silva, J. A. (2020). Impacts of hunting prohibitions on multidimensional well-being. Biological Conservation, 243, 108451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108451

- Sykes, G. M., & Matza, D. (1957). Techniques of neutralization: A theory of delinquency. American Sociological Review, 22(6), 664–670. https://doi.org/10.2307/2089195

- Travers, H., Archer, L. J., Mwedde, G., Roe, D., Baker, J., Plumptre, A. J., Rwetsiba, A., & Milner-Gulland, E. J. (2019). Understanding complex drivers of wildlife crime to design effective conservation interventions. Conservation Biology, 33(6), 1296–1306. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13330

- Twinamatsiko, M., Baker, J., Harrison, M., Shirkhorshidi, M., Bitariho, R., Wieland, M., Asuma, S., Milner-Gulland, E. J., Franks, P., & Roe, D. (2014). Understanding profiles and motivations of resource users and local perceptions of governance at Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, Uganda. International Institute for Environment and Development.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (2016). World wildlife crime report: Trafficking in protected species.

- van de Schoot, R., de Bruin, J., Schram, R., Zahedi, P., de Boer, J., Weijdema, F., Kramer, B., Huijts, M., Hoogerwerf, M., Ferdinands, G., Harkema, A., Willemsen, J., Ma, Y., Fang, Q., Hindriks, S., Tummers, L., & Oberski, D. L. (2021). An open source machine learning framework for efficient and transparent systematic reviews. Nature Machine Intelligence, 3(2), 125–133. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-020-00287-7

- van Velden, J., Wilson, K., & Biggs, D. (2018). The evidence for the bushmeat crisis in African savannas: A systematic quantitative literature review. Biological Conservation, 221, 345–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2018.03.022

- van Velden, J. L., Wilson, K., Lindsey, P. A., McCallum, H., Moyo, B. H. Z., & Biggs, D. (2020). Bushmeat hunting and consumption is a pervasive issue in African savannahs: Insights from four protected areas in Malawi. Biodiversity and Conservation, 29(4), 1443–1464. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-020-01944-4

- Von Essen, E., Hansen, H. P., Nordström Källström, H., Peterson, M. N., & Peterson, T. R. (2014). Deconstructing the poaching phenomenon. British Journal of Criminology, 54(4), 632–651. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azu022

- Yamagiwa, J. (2003). Bushmeat poaching and the conservation crisis in Kahuzi-Biega National Park, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Journal of Sustainable Forestry, 16(3–4), 111–130. https://doi.org/10.1300/J091v16n03_06