Abstract

Background The usefulness of a national medical register relies on the completeness and quality of the data reported. The data recorded must therefore be validated to prevent systematic errors, which can cause bias in reports and study conclusions.

Patients and methods We compared the number of hip replacements reported to the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register (NAR), 1987–2003, and to the Norwegian Patient Register (NPR), 1999–2002, with data recorded at a local hospital. The date of operation and the index hip were further validated to find inaccurately recorded data in the NAR. Kaplan-Meier estimated survival curves were compared to evaluate the possible influence of missing data.

Results Of 5,134 operations performed at a local hospital, 19 (0.4%) had not been reported to the NAR. Completeness of registration was poorer for revisions (1.2%) than for primary operations (0.2%). Among 86 Girdlestone revisions (removal of the prosthesis only), 9 (11%) had not been reported to the NAR. Missing data on revisions, however, had only a minor influence on survival analyses. The date of the operation had been recorded incorrectly in 56 cases (1.1%), and the index hip in 12 cases (0.2%). The surgeon was responsible for 85% of these errors. Comparisons with data reported to the NPR, 1999–2002, showed that 3.4% of operations at the local hospital had not been reported to the NPR.

Interpretation Only 0.4% of the data from a local hospital was missing in the NAR, as opposed to the NPR where 3.4% was missing. The information recorded in the NAR appears to have been valid and reliable throughout the entire period, and provides an excellent basis for clinically relevant information regarding total hip arthroplasty.

▪

Research based on national registers is a way of assessing the quality and results of surgery, and these registers can be used as a tool to monitor and improve treatment options (Havelin Citation1999, Sachs and Synnerman Citation1999). The Norwegian Arthroplasty Register (NAR) has published a number of important studies on implants and cements (Havelin et al. Citation2000). To ensure that such registers are useful and reliable, it is important to evaluate the quality of the data and to validate it (Goldberg et al. Citation1980). Several methods have been used to investigate the completeness of registration and validity of data in national clinical registries. The 3 most common methods are: 1. to compare national registry data with data from national Patient Administrative Systems (PAS) (Robertsson et al. Citation1999, Fender et al. Citation2000, Söderman et al. Citation2000, Puolakka et al. Citation2001, Pedersen et al. Citation2004, Espehaug et al. Citation2006), 2. to compare national registry data with local data found in registration forms, operation log books or patient records (Garne et al. Citation1995, Froen and Lund-Larsen Citation1998, Gunnarsson et al. Citation2003), and 3. to compare recorded data with data obtained from the patients using questionnaires (Robertsson et al. Citation1999). To obtain information of high quality, it is important to identify any systematic reporting and recording errors, or missing data.

In the present study, we have addressed possible differences in registrations in the NAR and the national Norwegian Patient Register (NPR), as compared to data from a local hospital. We have also validated the quality of selected data recorded in the NAR database. In addition, we have assessed the effect of missing data in the NAR on the results of prosthesis survival analyses.

Patients and methods

A local hospital database

A local database was established in 1998 at the Orthopedics Department of Stavanger University Hospital (SUH), including information obtained from the surgical logbook and patients'medical records. The orthopedic surgeon writes the name of the patient, the diagnosis and the type of operation in the surgical logbook immediately after the operation. The recording of operation codes constitutes the basis for the hospital's extra reimbursement from the government, and is considered to be complete and correct. To report the operation to the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register (NAR), the surgeon fills in a standard paper form immediately after the operation. Copies of the form are left in the patient medical record and the front-page is sent by mail to NAR for registration in the database.

The Norwegian Arthroplasty Register

The Norwegian Arthroplasty Register (NAR) was established in September 1987, and collects information prospectively on primary total hip arthroplasties (THA) and revisions performed in Norway. Any revision, defined as a surgical removal or as exchange of a part of or the whole implant, is linked to data already collected from the primary operation using the unique 11-digit identity (ID) number assigned to each inhabitant of Norway. Information is reported from all hospitals that perform hip arthroplasty. By December 31, 2003, data on 85,082 primary THA and 14,359 revisions had been recorded.

The quality of hip arthroplasty is evaluated based on prosthesis lifetime, i.e. the time from insertion of the implant until a possible revision. Consequently, the date of operation, the type of operation (primary or revision), and the index hip (left or right) all constitute important information to ensure correct survival analyses. Each primary THA or revision procedure is reported on a standard paper form which is sent to the registry. A secretary enters the information into the database manually (Havelin et al. Citation2000). The form contains information such as the patient's national ID number, date of operation, index hip, type of prosthesis, type of cement, duration of the surgery, operation method, use of bone transplantation, type of operating theatre, use of antibiotic prophylaxis and complications during surgery (Havelin Citation1999).

Use of the personal ID number made it possible to compare data recorded in the NAR database and the SUH database. If we found missing data or discrepancies in the data recorded, we searched through the patient's medical record manually and through the hospital patient administrative system to find the correct information. For every discrepancy, we also retrieved the paper copy of the NAR form from the patient's medical record. Based on this information, we classified the cause of the discrepancy to establish whether data had been wrongly entered into the NAR database, or whether the surgeon was responsible for these errors.

The Norwegian Patient Register

The Norwegian Patient Register (NPR) was established in March 1997 and receives reports on operative procedures extracted from the patient administrative systems at all hospitals in Norway. Patient age, sex, place of residence, hospital and department, diagnose(s), surgical procedure(s), and dates of admission and discharge are included in the registry (Bakken et al. Citation2004). The name and ID number of the patient are not included. From 1999, the registry included information about surgical procedures (classified according to the Norwegian NOMESCO Classification of Surgical Procedures (N-NCSP)).

In order to examine the completeness of THA and revision procedures in the NPR, we obtained statistics from the NPR for the years 1999–2002. The numbers we used were based on surgical procedure codes for primary implantation of total hip prostheses (NFB20, NFB30, NFB40, NFB59, NFB99), secondary implantation (NFC20-23, NFC29, NFC30-33, NFC39, NFC40-43, NFC49, NFC59, NFC99), and removal of implant component(s) (NFU00-09, NFU10-19).

Statistics

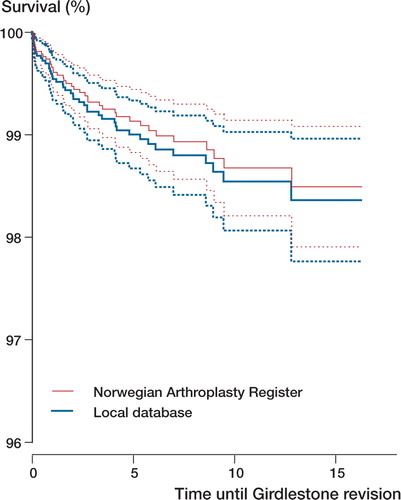

In order to investigate whether missing data on revisions in the NAR had any effect on conclusions on prosthesis lifetimes, Kaplan-Meier estimated survival curves were established for data in the NAR and for data in the local database at SUH. The survival analyses were performed with Girdlestone revision as the endpoint. A Girdlestone revision was defined as a revision where the primary prosthesis was removed without being replaced with new prosthetic components. The Central Bureau of Statistics, Oslo, provided information on deaths and emigrations until December 31, 2003. The survival times of THAs in patients who had died or who had emigrated without failure of the prosthesis, or revisions other than Girdlestone procedures, were censored at the time of death or emigration.

We used the statistical software program S-Plus 2000 (MathSoft Inc., Seattle, WA).

Results

During the years 1987–2003, 99,441 hip arthroplasty procedures were registered in the NAR. Among these, 5,115 were reported from the local hospital (SUH), which constituted 5.1% of the total number of operations. 5,134 operations had been registered in the local database at SUH. Thus, 19 operations (0.4%) at SUH were missing in the NAR database (). In addition, 6 primary THAs performed at other hospitals had been incorrectly recorded as being performed at SUH.

Table 1. Number of operations reported to Stavanger University Hospital (SUH) and the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register (NAR), 1987–2003

When we validated the information on the date of operation, we found 56 errors (1.1%), including 29 with the incorrect day, 17 with a wrongly recorded month, and 10 with the incorrect year. After investigation of these errors, we found that illegible handwriting had been the reason for wrong information in 27 cases. In 19 of the cases, the surgeon had written the wrong date, and in 10 cases typing errors at the NAR had resulted in wrong information. The surgeons were responsible for all errors regarding the year of the operation. During the first 7 weeks after New Year, the operation was wrongly reported as having been performed the previous year, and was thus registered in the NAR database as having taken place exactly one year before the surgery took place. We observed 12 (0.2%) right-left errors regarding the identity of the index hip, all due to incorrect information on the form. The surgeons were responsible for 85% of all these registration errors. gives the distribution of causes for incorrect registration of date and index hip in the NAR.

Table 2. Classification of causes of incorrect registration in the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register (NAR) of data reported from a local hospital

Primary operations

Of 85,082 primary THAs recorded in the NAR, 4,297 were reported from the local hospital SUH. According to the surgical logbook at SUH, 4,306 primary THAs had been performed. Thus, information about 9 (0.2%) primary THAs was missing from the NAR database (). Among these, 4 patients'medical records contained copies of the form that had been incompletely filled in, and 3 contained the original form (and copy) which had been filled in but had not yet been mailed to the NAR. No forms were found for 2 patients.

The date of the primary operation had been incorrectly recorded in 53 primary operations (1.2%). Examination of the index hip data showed 9 (0.2%) right-left errors.

Kaplan-Meier estimated survival curves with 95% confidence limits, for primary total hip replacements reported to the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register from a local hospital.The endpoint was defined as Girdlestone revision as registered by the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register (n = 39) and in the local database (n = 44).

Revisions

14,359 revision procedures were registered in the NAR. Of these, 818 had been reported by the SUH, while the local database contained 828 revision procedures. Thus, 10 revisions (1.2%) were missing from the NAR database. Regarding Girdlestone procedures, 11% (9/86) of the procedures had not been reported to the NAR (). No NAR forms were found in the medical records of these patients. Infection was the reason for revision in 8 of the 9 Girdlestone procedures not registered in the NAR. Of the 9, only 5 had had their primary operation after the NAR started registration. These missing revisions had only a minor effect on the survival analysis with Girdlestone revision as endpoint (Figure). The only missing exchange revision was performed 6 weeks after the NAR was started.

Regarding the date of the revision, we found incorrect reporting of day, month or year in 3 operations (0.4%). The validation of the index side showed 3 right-left errors (0.4%). 2 of the revisions had been recorded in the NAR as primary operations and both involved insertion of a new prosthesis after Girdlestone procedures.

Comparing SUH and NPR data

During a 4-year period 1,349 operations were recorded in the NPR, while 1,396 operations were registered at SUH (). Consequently, 47 operations (3.4%) were missing from the NPR. Among primary THRs, 0.4% were missing, and among revisions, 16% were missing. In the same period, 0.5% of all operations at SUH were not reported to the NAR.

Table 3. The number of operations reported to Stavanger University Hospital (SUH), the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register (NAR) and the Norwegian Patient Register (NPR) during the years 1999–2002

Discussion

We found that overall, 0.4% of the operative procedures performed at our local hospital were missing from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register (NAR) (). Nationwide, the completeness of registration for hip replacement was 98% (Espehaug et al. Citation2006), and at a smaller county hospital it was 93% (Froen and Lund-Larsen Citation1998). Compliance with other Scandinavian hip arthroplasty registers was between 90% and 95% (Puolakka et al. 1997, Söderman Citation2000, Pedersen et al. Citation2004). Comparison with the Norwegian Patient Register (NPR) showed that during the years 1999–2002, 3.4% of the operative procedures were not reported to the NPR. In the same period, 0.5% of all operations at SUH were not reported to the NAR.

In 1999, Robertsson found better reporting of knee arthroplasty revisions from university hospitals than from smaller units. On the other hand, in 1997, Puolakka et al. observed a large variation in registrations to the Finish Arthroplasty Register (65–99%) related to different types of hospitals, where a small regional hospital had the most complete reporting. SUH is a large teaching hospital with some of the largest numbers of elective hip operations in Norway. With data from only one hospital, it is difficult to generalize the reporting result for the whole country. We found no systematic errors in the reporting to the NAR. It is especially important for the revisions. Our study has also shown that the data recorded in the NAR database was of good quality, with only minor registration errors.

We observed inferior registration of Girdlestone procedures to the NAR, with 11% of the 86 procedures missing. Partial revisions and extraction of prosthesis components was also the most common procedure to be unreported to the Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register. Robertsson and coworkers (Citation1999) reported that comparisons of reports to the Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register and the Swedish Patient Administrative System (PAS) enabled them to trace 84% of unreported revisions. In the Swedish PAS register, patients are registered using their unique personal ID number, which is not the case in NPR. Registration of the patient's ID number in the NPR will be necessary if the NPR data is to be used as a reliable reference (Bakken et al. Citation2004).

In the literature, several kinds of registration errors have been considered (van der Putten et al. Citation1987, Knatterud et al. Citation1998). Sörensen et al. (Citation1996) described a system whereby they categorized errors into systematic and random ones, and they found that the most common reason for systematic errors was an unclear definition of data items or violation of the data collection protocol. In our case, the definition of revision surgery (procedures in which part of, or the whole prosthesis is exchanged or removed) was clear. However, some surgeons may have interpreted the word “revision” as meaning “exchange of implant” and thus may not have reported procedures with only removal of prosthetic components. The inferior reporting of Girdlestone procedures might influence estimated survival figures, in particular analyses with revision due to infection as endpoint. However, inclusion of missing Girdlestone operations gave only minor differences in prosthesis survival when investigated with Girdlestone revisions as end-point. With longer follow-up in the NAR, analyses may be influenced more by unreported Girdlestone revisions.

After checking of the date and the index side of the surgery, we found that the surgeon had been responsible for most of these errors. Erroneous typing at the NAR caused only 10 of 68 errors. The errors regarding dates and index side were random errors (except the wrongly given operation year), which should have negligible influence on the results. It has been shown that the most frequent causes of random errors are typing errors and illegible handwriting (Vantongelen et al. Citation1989, Knatterud et al. Citation1998). Recently, Arts et al. (Citation2002) suggested that in a central registry database, one can expect 5% inaccuracy and 5% incomplete data after transcription of data from paper forms. Our findings demonstrated a higher proportion of accurate data for selected variables. In a Dutch intensive care unit database based on case recorded forms, inaccurate typing accounted for 0.6% of the errors, and was thus a relatively infrequent cause of suboptimal data quality (Arts et al. Citation2002). These observations are in keeping with our findings.

The most important reason for the good quality of data in the NAR database is probably the well-qualified and stable secretarial manpower. Systematic and continuous efforts have been made to minimize the occurrence of missing or erroneous data in the NAR database. When errors or missing data are identified on the form, the form is returned to the local hospital for further information. The numbers of operations reported to the NAR and to the NPR are compared on a regular basis, and hospitals are notified as to any discrepancies in reported numbers. The reasons for the accurate registration in our local hospital are most likely the stable manpower and well-performed routines for immediate registration of the procedures after completion of the operation.

To conclude, our study confirms our expectations that the NAR database consisted of reliable data of high quality throughout the entire period. The study indicates that our previously published studies (Havelin et al. Citation2000) were based on good-quality data. The NAR can be used to provide results of significant clinical importance for the management of patients being operated on for hip arthroplasty. This source of information will allow a national assessment of the results of hip arthroplasty, which is important for society, for the community of responsible orthopedic surgeons, and finally for the individual patient. Nevertheless, there is still room for improvement, which remains a challenge for every reporting orthopedic surgeon.

No competing interests declared.

- Arts D, de Keizer N, Scheffer G J, de Jonge E. Quality of data collected for severity of illness scores in the Dutch National Intensive Care Evaluation (NICE) registry. Intensive Care Med 2002; 28(5)656–9

- Bakken I J, Nyland K, Halsteinli V, Kvam U H, Skjeldestad F E. The Norwegian Patient Registry. Nor J Epidemiol. 2004; 14(1)65–9

- Espehaug B, Furnes O, Havelin L I, Engesæter L B, Vollset S E, Kindseth O. Registration completeness i the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop 2006, Accepted

- Fender D, Harper W M, Gregg P J. The Trent regional arthroplasty study. Experiences with a hip register. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2000; 82(7)944–7

- Froen J F, Lund-Larsen F. Ten years of the Lubinus Interplanta hip prostheses. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 1998; 118(18)2767–71

- Garne J P, Aspegren K, Moller T. Validity of breast cancer registration from one hospital into the Swedish National Cancer Registry 1971-1991. Acta Oncol 1995; 34(2)153–6

- Goldberg J, Gelfand H M, Levy P S. Registry evaluation methods: a review and case study. Epidemiol Rev 1980; 2: 210–20

- Gunnarsson U, Seligsohn E, Jestin P, Påhlman L. Registration and validity of surgical complications in colorectal cancer surgery. Br J Surg 2003; 90(4)454–9

- Havelin L I. The Norwegian Joint Registry. Bull Hosp Jt Dis. 1999; 58(3)139–47

- Havelin L I, Engesaeter L B, Espehaug B, Furnes O, Lie S A, Vollset S E. The Norwegian Arthroplasty Register: 11 years and 73,000 arthroplasties. Acta Orthop Scand 2000; 71(4)337–53

- Knatterud G L, Rockhold F W, George S L, Barton F B, Davis C E, Fairweather W R, Honohan T, Mowery R, O'Neill R. Guidelines for quality assurance in multicenter trials: a position paper. Control Clin Trials 1998; 19(5)477–93

- Pedersen A B, Johnsen S P, Overgaard S, Søballe K, Sørensen H T, Lucht U. Registration in the danish hip arthroplasty registry. Acta Orthop Scand 2004; 75(4)434–41

- Puolakka T J S, Pajamäki J, Pulkkinen P Nevalainen. Cementless Biomet Total Hip prosthesis in the treatment of osteoarthrosis survivorship analysis, Publications of the national Agency for Medicines 3/1997

- Puolakka T J S, Pajamäki K J J, Halonen P J, Pulkkinen P O, Paavolainen P, Nevalainen J K. The Finnish Arthroplasty Register. Report of the hip register. Acta Orthop Scand 2001; 72(5)433–41

- Robertsson O, Dunbar M, Knutson K, Lewold, Lidgren L. Validation of the Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register. A postal survey regarding 30,376 knees operated on between 1975 and 1995. Acta Orthop Scand 1999; 70(5)467–72

- Sachs M A, Synnerman J E. Quality registries are a goldmine of information that should be better used. Knowledge of improvement is acquired by means of special projects. Lakartidningen 1999; 96(20)2438–40

- Söderman P. On the validity of the results from the Swedish National Total Hip Arthroplasty register. Acta Orthop Scand (Suppl 296) 2000; 71: 1–33

- Söderman P, Malchau H, Herberts P, Johnell O. Are the findings in the Swedish National Total Hip Arthroplasty Register valid? A comparison between the Swedish National Total Hip Arthroplasty Register, the National Discharge Register, and the National Death Register. J Arthroplasty 2000; 15(7)884–9

- Sörensen H T, Sabroe S, Olsen J. A framework for evaluation of secondary data sources for epidemiological research. Int J Epidemiol 1996; 25(2)435–42

- van der Putten E, van der Velden J W, Siers A, Hamersma E A M. A pilot study on the quality of data management in a cancer clinical trial. Control Clin Trials 1987; 8(2)96–100

- Vantongelen K, Rotmensz N, van der Schueren E. Quality control of validity of data collected in clinical trials. EORTC Study Group on Data Management (SGDM). Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol 1989; 25(8)1241–7