Abstract

Background Until now, surgical treatment has been the mainstay in the treatment of desmoid tumors, even though it is associated with a high recurrence rate. There have, however, been occasional case reports showing that desmoid tumors may spontaneously decrease in size or even disappear.

Patients and methods This is a retrospective review of 8 patients with abdominal (5) or extra-abdominal (3) desmoid tumors who were followed both clinically and with imaging techniques (sonography, CT or MRI). Mean follow-up time was 4.4 (0.8–7.5) years. Tumor volume was assessed in each investigation and followed over time.

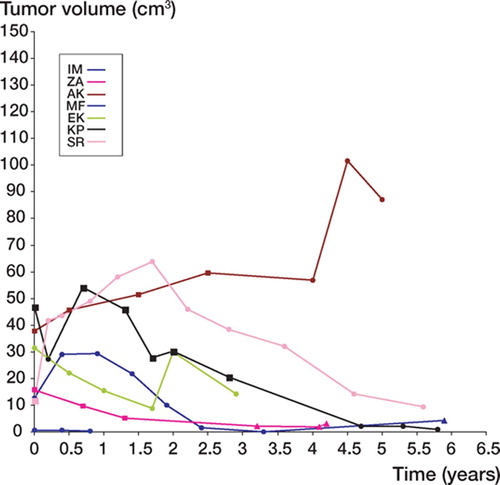

Results 3 tumors disappeared, 2 diminished in size, 1 did not change and 2 tumors became larger, 1 of which had trippled in volume at the latest follow-up.

Interpretation Desmoid tumors have probably been overtreated in the past. Many of them tend to regress spontaneously.

Desmoid-type fibromatoses (desmoid tumors or aggressive fibromatoses) are benign but locally aggressive tumors originating in musculoaponeurotic tissues. They mainly affect adolescents or young adults. Trauma has been suggested to be an etiologic factor (Penick Citation1937, Hunt et al. Citation1960, Dahn et al. Citation1963) and sex hormones may affect tumor growth (Reitamo et al. Citation1986). Although surgical treatment is associated with a high local recurrence rate (Rock et al. Citation1984), most authors still consider this to be the treatment of choice. Other treatment modalities such as radiation, antihormonal therapy, interferon, cytotoxic drugs, and isolated limb perfusion (ILP) have been tried alone or in combination with surgery but without conclusive effects (Waddell et al. Citation1983, Rock et al. Citation1984, Wilcken and Tattersall Citation1991, Fernberg et al. Citation1999, Lev-Chelouche et al. Citation1999, Leithner et al. Citation2000, Raguse et al. Citation2004). Spontaneous disappearance of desmoid tumors has occasionally been reported (Dahn et al. Citation1963, Enzinger and Shiraki Citation1967, Rock et al. Citation1984). The aim of this report was to assess the clinical and radiological outcome in a series of patients with desmoid tumors that were left without treatment.

Patients and methods

We retrospectively reviewed 8 patients with desmoid tumors, followed without any treatment at our department. 6 patients had primary tumors, 1 had a second local recurrence after repeated surgery, and 1 had remaining tumor after incomplete surgical excision. The patients either had small tumors that did not cause any symptoms, or large tumors that could not be removed or treated without risk of significant disability (). Mean follow-up time was 4.4 (0.8–7.5) years.

Table 1. Data on 8 patients with desmoid tumors

5 patients were women and 3 were men, with an average age of 35 (10–70) years. The mean duration of symptoms prior to diagnosis was 0.9 (0.5–3) years. The largest mean tumor diameter at the beginning of this study was 6.5 (2–11) cm. All patients presented with a palpable mass. 5 tumors were located in the abdominal wall, 1 in the triceps brachii muscle, 1 in the erector spinae muscle, and 1 in the pectoralis major muscle. 3 of 4 women with desmoid tumors in the abdominal wall were pregnant or within a month post-partum at tumor presentation.The diagnosis of desmoid tumors was based on morphological examinations (fine-needle aspiration cytology in all 8 cases and surgical specimens in 3 cases) in conjunction with clinical and imaging findings.

All patients were followed at our center with clinical examinations as well as with imaging techniques (CT or MRI) by 2 radiologists independently. Sonography was performed in 2 patients by one of the radiologists.

At CT, the maximum sagittal and transverse diameters were measured on the transverse images. The cranio-caudal extension of the tumors was calculated as the product of slice thickness and number of slices with visible tumor. At MRI, tumor diameters were measured in 3 planes: transverse, sagittal and coronal. The tumor volume was calculated according to Göbel et al. (Citation1987) and then plotted as a function of time ( and ).

Results

Imaging studies

At CT, the tumors appeared typically well-defined and ovoid when located in skeletal muscle, particularly when scanning perpendicular to the muscle fibers. The tumors were usually iso-attenuating with skeletal muscle on native scans, which made small tumors hard to detect and delineate. The tumors showed a high and homogeneous enhancement after intravenous contrast administration.

On MRI, the tumors usually showed moderate to high signal on T2-weighted images, sometimes with a partially mottled pattern. There was a moderately low signal comparable to skeletal muscle on T1-weighted images, usually with a high and homogeneous enhancement after intravenous administration of Gadolinium contrast. The extent of the tumors could be best estimated on T2weighted images and on T1-weighted images with contrast enhancement. The tumors were not as well delineated by sonography as by CT or MRI.

Abdominal desmoid tumors

None of the 5 patients (4 women) had any symptoms except for a palpable mass (). 1 woman (MF) was referred after surgery, which left a small macroscopic residual tumor. She was followed clinically and by MRI. At latest follow-up, 0.8 year postoperatively, the tumor was stable. In 1 woman (KP), a desmoid tumor originated in the operation scar 2 years after nephrectomy. During the early part of the observation period, the patient received estrogen treatment for postmenopausal symptoms. Clinical examination and CT scans revealed an increase in tumor volume. The estrogen treatment was terminated and then the tumor decreased in size. After 5.8 years of follow-up, there was an almost complete remission (black curve in ). The remaining 2 female patients (ZA, AK) with desmoid tumors in the abdominal wall were followed for 4.2 and 5 years, respectively. 1 patient (ZA) declined a fourth CT or MR investigation, and sonography was performed instead. The tumor had diminished in size. The other tumor increased during the first 4.5 years, followed by a decline at latest follow-up. The male patient (JS), who had a large desmoid tumor in the abdominal wall, had no previous history of trauma. At latest follow-up, 2.7 years after diagnosis, the tumor had increased considerably in size ().

Extra-abdominal desmoid tumors

3 patients (2 men) had extra-abdominal desmoid tumors. The female patient with a tumor in the pectoralis major muscle (IM) had a fracture in the proximal humerus treated with external fixation 1.7 years before diagnosis. An increase in tumor size was observed during the early phase of observation. At latest MRI, 3.3 years after diagnosis, the tumor had disappeared. 5.9 years after diagnosis, sonography (the patient refused other investigations) showed a small, poorly circumscribed irregular lesion that was not palpable.

A 10-year-old boy (SR) had a large desmoid tumor involving the entire cross section of the distal part of his right triceps brachii muscle. Neither surgical treatment aiming at complete removal of the tumor nor radiotherapy were attractive treatment alternatives in this growing child. A decision was taken to only follow the development. The tumor initially grew during the first 2 years, but subsequently decreased in size and at follow-up 5.6 years after diagnosis, there was an almost complete remission. At the latest clinical examination 7.5 years after diagnosis, there was no palpable tumor. The patient refused any further MR investigations ().

Figure 3. Sagittal T1-weighted MR images (after gadolinium administration) of a desmoid tumor of the left triceps brachii muscle in a boy who was 10 years old at diagnosis. A. 0.4 years after diagnosis. B. 1.2 years after diagnosis. C. 2.2 years after diagnosis. D. 3.6 years after diagnosis, with considerable regression.

1 male patient (EK) with a desmoid tumor in the back was primarily operated with a marginal margin. He developed a recurrent tumor 1.2 years later, which was again removed surgically with a wide margin. A second recurrence was evident on MRI after another 0.8 year. The patient was symptom-free and no further treatment was given. Repeated MR investigations were performed. The tumor initially decreased in size, but about 1.5 years after detection of the recurrence, it started to grow and reached a peak at 2 years follow-up. At the latest follow-up (2.9 years), the tumor had decreased considerably in size.

Discussion

Local recurrence after surgical removal of desmoid tumors is common (19–77%) (Musgrove and McDonald Citation1948, Hunt et al. Citation1960, Enzinger and Shiraki Citation1967, Das Gupta Citation1968, Rock et al. Citation1984, Karakousis et al. Citation1993) and is a major problem. For this reason, many alternative treatments have been tried but with varying results. Radiotherapy, alone or given postoperatively, has been associated with high local control rates in some studies (Kiel and Suit Citation1984, McCollough et al. Citation1991, Karakousis et al. Citation1993, Kamath et al. Citation1996, Nuyttens et al. Citation2000) but not in others (Merchant et al. Citation1999, Citation2000, Pignatti et al. Citation2000). Chemotherapy has also been tried in the treatment of desmoid tumors with variable results (Easter and Halasz Citation1989, Raney Citation1991, Patel et al. Citation1993). Good responses to vinblastine and methotrexate or doxorubicin as a single agent have been found in studies involving a small number of patients (Weiss and Lackman Citation1989, Seiter and Kemeny Citation1993). In a recent report with a systematic review of published trials, studies and case series, it was noted that almost 50% of patients are likely to respond to chemotherapy (Janinis et al. Citation2003). The mortality rate for desmoid tumor is around 1% (Rock et al. Citation1984); deaths are associated with involvement of vital organs. The natural course of the disease remains obscure.

In a previous study (Dalén et al. Citation2003), we reviewed 30 patients with more than 20 years follow-up. 12 had a local recurrence after surgery. All kinds of treatments including multiple surgery, radiation, and anti-estrogen were given. A few cases were left without further treatment. At a mean follow-up of 28 years, all patients but 1 were tumor-free. 1 patient had had a stable tumor for 11 years. These findings and a few case reports on spontaneous regression of desmoid tumors prompted us to leave some patients without treatment, i.e. patients with small tumors or with tumors for which surgical treatment might be severely disabling and likely to be followed by complications. These consequences may also result from full-dose irradiation.

In 8 of our cases, the diagnoses were established with fine-needle aspiration (FNA). The cytological findings in the desmoid tumors were typical, with groups of loosely cohesive, bland-appearing spindle-shaped cells (Raab et al. Citation1993). The diagnoses were confirmed with surgical specimens in 3 cases. The MR and CT images were also suggestive of desmoid tumors, with ovoid-shaped lesions intramuscularly and with rather homogenous contrast enhancement.

Many textbooks and reports differentiate between abdominal and extra-abdominal desmoid tumors, although the morphological and immunohistochemical findings are identical. The reason for separating these groups is the association of abdominal desmoid tumors with pregnancy and the lower local recurrence rate in abdominal desmoids following surgery. In our study, we found no reason to exclude abdominal lesions when we instituted a stronger policy of no treatment.

Our study was retrospective, which explains why the patients were followed with different imaging modalities. However, most of the investigations were done with MRI. CT gives an excellent delineation of the tumor when the scans are perpendicular to the direction of the fibers in the involved muscle, while the tumor extension in the muscle fiber direction may be less distinct. MRI, with its multiplanar imaging capabilities, high inherent contrast resolution and avoidance of ionising radiation makes it the method of choice for serial investigations of desmoid tumors. If evaluation of size alone is necessary, intravenous contrast administration can be avoided. Sonography is a simple and cheap method but requires skill and experience; even so, the measurements are not as precise as with MRI or CT. Also, large tumors are difficult to examine. As expected, there was interobserver variation in the assessement of tumor volumes between the two radiologists. Thus, consecutive investigations should be assessed by the same radiologist.

Our small retrospective series does not allow us to make conclusions on the natural course of desmoid tumors. However, our findings point to a more favorable development of desmoid tumors than the aggressive macro- and microscopic growth patterns might indicate. In our series, 2 of 8 tumors increased in size. 1 of these had an initial size that exceeded that of the other tumors several times. At 2.7-years follow-up it had trippled its size. Whether this indicates another type of biological behavior remains to be seen. 6 other tumors showed an undulating variation in size which might indicate periodic influence of as yet unknown factors. Our series of 8 patients is too small to allow any specific recommendation as to the need of or time for intervention—or to assess whether particular tumor locations are more favorable than others. A randomized prospective study with long-term follow-up might solve this issue. However, our findings together with case reports on spontaneous regression (Dahn et al. Citation1963, Rock et al. Citation1984) and a report on stable tumors (Pignatti et al. Citation2000) suggest that most desmoid tumors should probably be left alone. Whether tumors may occasionally progress indefinitely is still unclear.

This work was supported financially by the Johan Jansson Foundation for Cancer Research and grants from the Swedish government under the LUA/ALF agreement.

No competing interests declared.

Contributions of authors

MD and PB examined patient files, reviewed clinical data, performed clinical examinations of patients and wrote an outline of the manuscript. BG contributed ideas and an outline of the study, and prepared the final manuscript in collaboration with the other authors. MG and HK reviewed all imaging analyses and contributed to parts of the manuscript.

- Dahn I, Jonsson N, Lundh G. Desmoid tumors. A series of 33 cases. Acta Chir Scand 1963; 126: 305–14

- Dalén B P M, Bergh P M, Gunterberg B U. Desmoid tumors: a clinical review of 30 patients with more than 20 years' follow-up. Acta Orthop Scand 2003; 74: 455–9

- Das Gupta T K, Brasfield R D, O'Hara J. Extra-abdominal desmoids. A clinicopathological study. Ann Surg 1968; 170: 109–21

- Easter D W, Halasz N A. Recent trends in the management of desmoid tumors. Summary of 19 cases and review of the literature. Ann Surg 1989; 210: 765–9

- Enzinger F M, Shiraki M. Musculo-aponeurotic fibromatosis of the shoulder girdle (extra- abdominal desmoid). Analysis of thirty cases followed up for ten or more years. Cancer 1967; 20: 1131–40

- Fernberg J O, Brosjo O, Larsson O, Soderlund V, Strander H. Interferon-induced remission in aggressive fibromatosis of the lower extremity. Acta Oncol 1999; 38: 971–2

- Göbel V, Jurgens H, Etspuler G, Kemperdick H, Jungblut R M, Stienen U, Gobel U. Prognostic significance of tumor volume in localized Ewing's sarcoma of bone in children and adolescents. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 1987; 113: 187–91

- Hunt R, Morgan H, Ackerman L. Principles in the management of extra-abdominal desmoids. Cancer 1960; 13: 825–36

- Janinis J, Patriki M, Vini L, Aravantinos G, Whelan J S. The pharmacological treatment of aggressive fibromatosis: a systematic review. Ann Oncol 2003; 14: 181–90

- Kamath S, Parsons J, Marcus R, Zlotecki R, Scarborough M. Radiotherapy for local control of aggressive fibromatosis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1996; 36: 325–8

- Karakousis C P, Mayordomo J, Zografos G C, Driscoll D L. Desmoid tumors of the trunk and extremity. Cancer 1993; 72: 1637–41

- Kiel K, Suit H. Radiation therapy in the treatment of aggressive fibromatosis (desmoid tumors). Cancer 1984; 54: 2051–??

- Leithner A, Schnack B, Katterschafka T, Wiltschke C, Amann G, Windhager R, Kotz R, Zielinski C C. Treatment of extra-abdominal desmoid tumors with interferonalpha with or without tretinoin. J Surg Oncol 2000; 73: 21–5

- Lev-Chelouche D, Abu-Abeid S, Nakache R, Issakov J, Kollander Y, Merimsky O, Meller I, Klausner J M, Gutman M. Limb desmoid tumors: a possible role for isolated limb perfusion with tumor necrosis factor-alpha and melphalan. Surgery 1999; 126: 963–7

- McCollough W, Parsons J, van der Griend R, Enneking W, Heare T. Radiation therapy for aggressive fibromatosis: the experience at the University of Florida. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1991; 73: 717–25

- Merchant N B, Lewis J J, Woodruff J M, Leung D H, Brennan M F. Extremity and trunk desmoid tumors: a multifactorial analysis of outcome. Cancer 1999; 86: 2045–52

- Merchant T E, Nguyen D, Walter A W, Pappo A S, Kun L E, Rao B N. Long-term results with radiation therapy for pediatric desmoid tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2000; 47: 1267–71

- Musgrove J E, McDonald J R. Extra-abdominal desmoid tumors. Their differential diagnosis and treatment. Arch Pathol 1948; 45: 513–40

- Nuyttens J J, Rust P F, Thomas C R, Jr., Turrisi A T, 3rd. Surgery versus radiation therapy for patients with aggressive fibromatosis or desmoid tumors: A comparative review of 22 articles. Cancer 2000; 88: 1517–23

- Patel S, Evans H, Benjamin R. Combination chemotherapy in adult desmoid tumors. Cancer 1993; 72: 3244, ??

- Penick R. Desmoid tumors developing in operative scars. Intern Surg Digest 1937; 23: 323–9

- Pignatti G, Barbanti-Brodano G, Ferrari D, Gherlinzoni F, Bertoni F, Bacchini P, Barbieri E, Giunti A, Campanacci M. Extraabdominal desmoid tumor. A study of 83 cases. Clin Orthop 2000, 375: 207–13

- Raab S S, Silverman J F, McLeod D L, Benning T L, Geisinger K R. Fine needle aspiration biopsy of fibromatoses. Acta Cytol 1993; 37: 323–8

- Raguse J D, Gath H J, Oettle H, Bier J. Interferon-induced remission of rapidly growing aggressive fibromatosis in the temporal fossa. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2004; 33: 606–9

- Raney R B, Jr. Chemotherapy for children with aggressive fibromatosis and Langerhans' cell histiocytosis. Clin Orthop 1991, 262: 58–63

- Reitamo J J, Scheinin T M, Hayry P. The desmoid syndrome. New aspects in the cause, pathogenesis and treatment of the desmoid tumor. Am J Surg 1986; 151: 230–7

- Rock M G, Pritchard D J, Reiman H M, Soule E H, Brewster R C. Extra-abdominal desmoid tumors. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1984; 66: 1369–74

- Seiter K, Kemeny N. Successful treatment of a desmoid tumor with doxorubicin. Cancer 1993; 71: 2242–4

- Waddell W, Gerner R, Reich M. Nonsteroid anti-inflammatory drugs and tamoxifen for desmoid tumors and carcinoma of the stomach. J Surg Oncol 1983; 22: 197–211

- Weiss A J, Lackman R D. Low-dose chemotherapy of desmoid tumors. Cancer 1989; 64: 1192–4

- Wilcken N, Tattersall M H. Endocrine therapy for desmoid tumors. Cancer 1991; 68: 1384–8