Abstract

Background Both components of the Kudo type 5 elbow prosthesis can be inserted with or without the use of cement. There have been no reports on the use of this prosthesis with all components uncemented in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Patients and methods We reviewed 49 primary uncemented Kudo type 5 elbow prostheses, inserted in 36 patients with rheumatoid arthritis, after mean 6 (2–10) years. Patients were assessed clinically both pre- and postoperatively (pain, instability, motion, ulnar neuropathy) and radiographically. Furthermore, at the time of follow-up clinical outcome was assessed using the Elbow Function Assessment Scale.

Results At review, 7 of 49 elbows had undergone revision because of symptomatic loosening of the ulnar component. In 42 unrevised elbows, clinical outcome was excellent in 29, good in 7, fair in 5, and poor in one. 31 of 42 elbows had no pain; 11 were painful at rest (VAS 1–2) and/or as a result of activity (VAS 1–8). With revision as endpoint, survival was 86% at 6 years. Intraoperative malpositioning of the ulnar component with a valgus or varus alignment of < 5° was associated with worse survival.

Interpretation We found an unexpectedly high rate of loosening of the ulnar component, which was associated with intraoperative malpositioning of the prosthesis. The ulnar component of this prosthesis should not be inserted without cement in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Various types of linked and unlinked, minimally- or semi-constrained total elbow prostheses are available for the treatment of patients with advanced rheumatoid arthritis (Van Der Lugt and Rozing Citation2004). The Kudo elbow prosthesis has been used since 1972 (Kudo et al. Citation1980) (). It is an unlinked, minimally-constrained prosthesis and its design has undergone several revisions: types 1 and 2 were cemented unstemmed surface replacements; in type 3 a stem was added to the humeral component, and type 4 permitted the insertion of both components without the use of cement (Kudo et al. Citation1980, Citation1994, Citation1999, Kudo and Iwano Citation1990). The current Kudo type 5 elbow prosthesis consists of a humeral component of cobalt-chromium alloy; it is one-half porous-coated with titanium alloy and has an ulnar component that is either all-polyethyl-ene for use with cement or metal-backed with titanium stem with or without a porous coat, for use without cement (Kudo et al. Citation1999). The standard ulnar component has a short stem; a long-stemmed ulnar component has been designed for revision surgery. We report our experience with the uncemented Kudo type 5 elbow prosthesis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, and investigate possible causes of radiographic loosening and subsequent failure.

Patients and methods

Since 1993, we have inserted 49 primary uncemented Kudo type 5 elbow prostheses (Biomet Inc., Warsaw, IN) in 36 patients (mean age 56 (23–83) years, 23 women) with rheumatoid arthritis and have followed them for a mean of 6 (2–10) years. All patients met the diagnostic criteria of the American Rheumatism Association for rheumatoid arthritis (Arnett et al. Citation1988) and indications for surgery were intractable pain and/or disabling loss of function.

Patients were assessed clinically preoperatively and at follow-up for pain (VAS) (0–10), medial collateral ligament instability (mild = < 3 mm, moderate = 3–6 mm opening, or severe < 6 mm joint space opening at 60° of flexion under valgus load at physical examination), range of motion (ROM), and for the presence of ulnar neuropathy. Preoperatively, the average pain score was 4 (0– 9) at rest and 7 (3–9) on activity. There was mild instability in 2 elbows, moderate in 16, and severe instability in 9. The average flexion was 127° (80– 150), extension deficit 39° (0–95), pronation 49° (0–90), and supination 50° (0–90).

At the time of follow-up, clinical outcome was assessed using the elbow function assessment scale (EFA) (de Boer et al. Citation1999, Citation2001). The EFA grades the clinical outcome on a 100-point scale (100–90 excellent, 89–80 good, 79–60 fair, < 60 poor); it combines results of clinical examination and capabilities regarding everyday living activities.

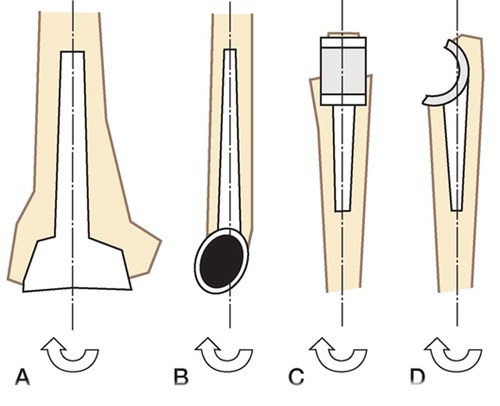

Preoperatively, all elbows were graded radiographically according to Larsen et al. (Citation1977); 26 elbows were grade IV and 23 were grade V. Intraoperative positioning of the elbow prosthesis was assessed on anteroposterior (AP) and lateral plain radiographs obtained 6 weeks postoperatively. Varus or valgus and flexion or extension alignment of the components relative to the axis of the proximal ulna and distal humerus, respectively, was measured in a standardized way on digitized plain straight AP- and lateral (elbow in 90° flexion) radiographs of both components (). Subluxation of the prosthesis was documented (). At follow-up, all prostheses were evaluated for position of the prosthesis, alignment and radiolucency around the components, fractures, and heterotopic ossification. Definitive radiographic loosening was defined as radiolucent lines of more than 1 mm in width around the entire component. In an attempt to classify heterotopic ossification, we used the the Brooker classification (Brooker et al. Citation1973) for ectopic ossification after total hip replacement.

Figure 2. Schematics used to determine the malalignment of the components. A–D: ideal alignment of the components; the axis of the component is parallel to the defined axis of the humerus and ulna, respectively. Deviation from the axis in valgus-varus and flexion-extension was measured in degrees (arrow).

Figure 3. Postoperative lateral and AP radiograph (case 25; Table). The humeral component is positioned in varus; the ulnar component is positioned in varus and flexion. The malalignment relative to the axis of the bone is illustrated. Also, note the subluxation with valgus tilt of the prosthesis.

Statistics

We used SPSS statistical software (version 11.5) and p-values of < 0.05 with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were considered significant. Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier technique with revision surgery as endpoint.

Operative technique

All procedures were performed in a similar way by the two senior authors (DE and MdeV). The elbow joint is exposed through a straight posterior incision and a U-shaped triceps flap is created. A transverse incision is made through the triceps aponeurosis, starting at the intermuscular aponeurosis at a point 8–10 cm proximal to the tip of the olecranon and directed distally through the fascia covering the lateral head of the triceps and anconeus, and ending at the subcutaneous border. The distally-based flap of triceps aponeurosis is temporarily secured with a ‘stay’ suture more distally on the ulna. The triceps is split, respecting its muscle fibers. The lateral ulnar collateral ligament is left intact and the annular ligament is opened to facilitate the luxation of the radial head in slight flexion and supination; the radial head is resected and synovitis, if present, is excised. The medial collateral ligament is then transected at the medial epicondyle to gain access to the joint. The ulnar nerve is identified proximal to the medial epicondyle and distally between the two heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris; it was not routinely transposed to its anterior subcutaneous pocket, nor decompressed. In 4 elbows that had ulnar neuropathy preoperatively, however, the ulnar nerve was decompressed and transposed (Table). All humeral and ulnar components were inserted without the use of cement. The aim was to insert an ulnar component with a long stem in all elbows; if the size of the medullary canal did not allow the insertion of a long ulnar stem, a short one was inserted. A long ulnar stem was used in 22 elbows. No bone grafting was necessary.

Postoperatively, all patients performed activeassisted flexion and pro- and supination exercises with the help of a physiotherapist. Active extension was not allowed for 4 weeks; thereafter, active and passive strengthening exercises were started. Patients wore a 90° resting splint during daytime and at night for 6 weeks.

Results

There were 2 intraoperative complications: 1 fracture of the medial epicondyle that required no treatment, and 1 ulna shaft fracture that was treated with cerclage wiring. Both patients had an excellent outcome (Table). 1 patient (no. 18, Table) had loss of motor function of the radial nerve postoperatively, which resolved within a year and was possibly caused by compression from a hematoma.

Excluding the 7 revisions (see below), there were 22 complications postoperatively, 14 of which required reoperation. There was ulnar neuropathy in 11 elbows; in 4 elbows the ulnar nerve was decompressed and transposed. 1 patient developed a superficial wound infection that was treated with intravenous antibiotics. 1 patient had a limited range of motion at 2.5 months postoperatively, and in 2 elbows (2 patients) the motion slowly decreased over time. These 3 elbows were treated with open arthrolysis.

Details of all 49 patients in the series

7 elbows required revision after an average of 4 years (1.5–8) because of symptomatic loosening of the ulnar component; 1 elbow was radiographically lost. In 6/7 cases the ulnar component was revised, and in 1 elbow a linked (Coonrad-Morrey) prosthesis was inserted (Table, ).

Figure 4. Lateral and AP radiographs of the same prosthesis as in , 2 years after insertion. There is marked osteolysis around the ulnar stem (white arrows).

Figure 5. Lateral and AP radiographs of the same prosthesis at the time of revision (4.6 years after implantation); osteolysis around the ulnar stem has caused fracture of the ulna (white arrows).

For the 42 unrevised elbows the clinical outcome was excellent in 29, good in 7, fair in 5, and poor in 1 (Table). There was no pain in 31 of the 42 elbows, and 11 were painful at rest (VAS 1–2) and/or during activity (VAS 1–8). There was mild instability in 5 elbows, moderate instability in 6, and ulnar neuropathy in 4. Average flexion was 133° (115–150), extension deficit 32° (5–90), pronation 70° (20–90), and supination 51° (0–90). The increase in motion was significant (p = 0.001, paired Student's t-test).

Legends to Table

Radiographically, 2 humeral components showed signs of progressive radiolucency around the barrel. There was progressive radiolucency in 4 ulnar components and definitive radiographic loosening in 1 (Case 49; Table). In 4 elbows there was a valgus tilt with subluxation of the ulna; this was associated with progressive radiolucency of the ulnar component in 2 of the 4. There was heterotopic ossification in 14 elbows, 9 Brooker grade I and 5 grade II.

Correlation of radiographic and clinical findings showed that the clinical outcome in the elbows that had radiographic signs of ulnar or humeral loosening was excellent in 4, fair in 2, and poor in 1 (Table).

In 11 of 49 elbows there was a valgus or varus alignment of the ulnar component of < 5° postoperatively. 5 had to undergo subsequent revision for loosening of the ulnar component and 3 had progressive ulnar radiolucency at follow-up. 4 of the 7 revised elbows had a varus or valgus alignment of the ulnar component of < 10° (Table). There was a correlation between revision and/or radiolucency at follow-up and an ulnar valgus/varus alignment of the ulnar component of < 5° (p = 0.001, Pearson's chi-square test). Furthermore, the mean valgus/varus alignment of the ulnar component differed between the 7 elbows that had been revised, the 7 that had progressive radiolucency at followup, and the 32 elbows that had neither (p = 0.007, Kruskal-Wallis test). Logistic regression showed that the odds of not having either to undergo revision or to have progressive radiolucency at followup were 13 times greater in elbows that had no ulnar valgus/varus alignment of < 5° (CI 2.6–66, p = 0.001). There was no significant correlation, however, between ulnar stem size and revision, and ulnar stem size and the presence of progressive radiolucency (Pearson's chi-square test). There was no relation between pre- and/or postoperative instability and survival.

Discussion

In unconstrained (unlinked) resurfacing elbow arthroplasty, stability is maintained by the surrounding ligaments. Theoretically, because of this the transmission of forces across the implant is less—reducing the risk of loosening. Furthermore, a more anatomical articulation is achieved, and minimal resection of bone is required, preserving bone stock for revision surgery if necessary (Verstreken et al. Citation1998, Potter et al. Citation2003). Unlinked implants have been associated with dislocation, ulnar neuropathy, infection and wound problems, however (Ferlic Citation1999). The Kudo type 5 elbow prosthesis is an unlinked minimally-constrained surface replacement that can be inserted with or without the use of cement (Kudo et al. Citation1999). We have found no reports on the use of the Kudo type 5 elbow prosthesis in which all ulnar and humeral components were inserted without the use of cement in patients with RA.

We achieved good pain relief and gain of function in the unrevised elbows, which is in accordance with previous reports on Kudo total elbow arthroplasty (Verstreken et al. Citation1998, Kudo et al. Citation1999, Rahme Citation2002, Potter et al. Citation2003). Radiographically, there was no migration or fracture of the humeral component of the implant—suggesting that previous problems with the stem of the humeral component of the type 4 Kudo such as metallosis, osteolysis, and ultimately breakage, appear to have been resolved with the Kudo type 5 prosthesis (Kudo et al. Citation1994, Citation1999). Similar findings concerning ulnar radiolucency have been reported by others. It should be noted that only Kudo et al. (Citation1999) used an uncemented ulnar component in some but not all of their patients. Potter et al. (Citation2003) reported 2 cases of progressive radiolucency—but no revisions—in 29 cemented Kudo type 5 elbow prostheses, with a mean follow-up of 6 years. Rahme (Citation2002) noted radiolucent lines around the cement-bone interface of the proximal part of the ulnar component in 17, and around the ulnar stem in 7, of 30 elbows. Kudo et al. (Citation1999) reported no radiolucent lines in 11 uncemented ulnar components, but in 32 cemented ulnar components there was partial radiolucency in 6 and complete radiolucency in one, with an average follow-up of 3 years and 10 months.

Van der Lugt and Rozing (Citation2004) provided an overview of aseptic loosening rates in a systematic review of primary elbow prostheses used for the rheumatoid elbow. 6 types of non-constrained (unlinked minimally constrained) prosthesis, including the Kudo type 5 elbow prosthesis, and 1 type of semi-constrained prosthesis (the GSBIII) were included and 23 series of implants were studied in total. Overall aseptic loosening rates, with or without revision, for each type of implant varied from 0.8% to13% (follow-up time 3–13 years). Gschwend et al. (Citation1999) reported that 32 of the GSBIII prostheses remained in situ in a series of 36 elbows that were examined clinically and radiographically after a mean period of 14 years; complications included 3 cases of aseptic loosening, 3 deep infections, and disassembly of the prosthesis in 9 cases. Gill and Morrey (Citation1998) described a series of 78 elbows managed with the semi-con-strained Coonrad-Morrey prosthesis with a 10–15-year follow-up; 2 revisions were performed for aseptic loosening. In our series, symptomatic loosening of the ulnar component resulted in failure of the prosthesis in 7/49 cases—which is higher then expected. It appears from statistical analysis that subluxation of the components and the malalignment of the ulnar component influence the outcome.

The malpositioning of the ulnar component and the subsequent high rate of problems are possibly due to absence of anatomical landmarks of the ulna and the insufficiency of aiming devices, which makes adequate intraoperative positioning difficult. It may, however, also be that problems with the ulnar component of the uncemented Kudo type 5 elbow prosthesis are related to the design and fixation properties of the ulnar part of the implant itself, and that this type of uncemented press-fit component is not suitable for use in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Another possible explanation for the high rate of loosening in our series is the relatively thin (2–3-mm) polyethylene layer in the Kudo prosthesis.

It can be argued that in our series revisions 1 and 2 (nos. 47 and 48, Table) should be excluded from the survival analysis because failure was due to gross malpositioning of the implant; neither elbow had a period of proper functioning postoperatively. Both required almost immediate revision and were thus not representative of the survival of the prosthesis, but can be considered to be part of the learning curve. With revisions 1 and 2 excluded, survival in this series was 89% (CI 79–99).

Currently, we insert the humeral component without cement and the ulnar component with cement. To overcome the problem of malpositioning of the prosthesis, we have developed a new extramedullary aiming device for the ulna and a new cutting block for the distal humerus. Furthermore, for elbows that are grossly unstable preoperatively, we use a semi-constrained prosthesis (CoonradMorrey). A potentially more definitive solution for malpositioning of the prosthesis would be com-puter-navigated surgery.

Contributions of authors

J-MB: wrote the article, did the follow-up of the patients and gathered all data. JdV and DE: designed the scoring forms, scored the patients preoperatively and scored the radiographs and revised the manuscript written by J-MB.

No competing interests declared.

The authors wish to thank P. G. Anderson for her help with the statistical analysis.

References

- Arnett F C, Edworthy S M, Bloch D A, McShane D J, Fries J F, Cooper N S, Healey L A, Kaplan S R, Liang M H, Luthra H S. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1988; 31: 315–24

- Brooker A F, Bowerman J W, Robinson R A, Riley L H, Jr. Ectopic ossification following total hip replacement. Incidence and a method of classification. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1973; 55: 1629–32

- de Boer Y A, van den Ende C H, Eygendaal D, Jolie I M, Hazes J M, Rozing P M. Clinical reliability and validity of elbow functional assessment in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 1999; 26: 1909–17

- de Boer Y A, Hazes J M, Winia P C, Brand R, Rozing P M. Comparative responsiveness of four elbow scoring instruments in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2001; 28: 2616–23

- Ferlic D C. Total elbow arthroplasty for treatment of elbow arthritis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1999; 8: 367–78

- Gill D R, Morrey B F. The Coonrad-Morrey total elbow arthroplasty in patients who have rheumatoid arthritis. A ten to fifteen-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1998; 80: 1327–35

- Gschwend N, Scheier N H, Baehler A R. Long-term results of the GSB III elbow arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1999; 81: 1005–12

- Kudo H, Iwano K. Total elbow arthroplasty with a non-con-strained surface-replacement prosthesis in patients who have rheumatoid arthritis. A long-term follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1990; 72: 355–62

- Kudo H, Iwano K, Watanabe S. Total replacement of the rheumatoid elbow with a hingeless prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1980; 62: 277–85

- Kudo H, Iwano K, Nishino J. Cementless or hybrid total elbow arthroplasty with titanium-alloy implants. A study of interim clinical results and specific complications. J Arthroplasty 1994; 9: 269–78

- Kudo H, Iwano K, Nishino J. Total elbow arthroplasty with use of a nonconstrained humeral component inserted without cement in patients who have rheumatoid arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1999; 81: 1268–80

- Larsen A, Dale K, Eek M. Radiographic evaluation of rheumatoid arthritis and related conditions by standard reference films. Acta Radiol Diagn (Stockh) 1977; 18: 481–91

- Potter D, Claydon P, Stanley D. Total elbow replacement using the Kudo prosthesis. Clinical and radiological review with five- to seven-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2003; 85: 354–7

- Rahme H. The Kudo elbow prosthesis in rheumatoid arthritis: a consecutive series of 26 elbow replacements in 24 patients followed prospectively for a mean of 5 years. Acta Orthop Scand 2002; 73: 251–6

- Van Der Lugt J C, Rozing P M. Systematic review of primary total elbow prostheses used for the rheumatoid elbow. Clin Rheumatol 2004; 23: 291–8

- Verstreken F, De Smet L, Westhovens R, Fabry G. Results of the Kudo elbow prosthesis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a preliminary report. Clin Rheumatol 1998; 17: 325–8