Abstract

Background Knee arthrodesis with external fixation (XF) is a possible salvage procedure for infected total knee arthroplasties (TKA). We report the outcome in 10 patients who underwent arthrodesis with the Sheffield Ring Fixator.

Patients and methods The patients had primary arthrosis in 8 cases; 2 cases were due to rheumatoid arthritis and sclerodermia. The mean time between the primary TKA and arthrodesis was 6 (0.5–14) years. The average age at arthrodesis was 69 years. The average follow-up period was 10 months.

Results Stable fusion was obtained in 6 patients after a mean XF time of 3.6 (2–4) months. 1 patient was referred to another hospital because of nonunion. This patient showed fusion with intramedullary nailing after 7 months. 3 nonunion patients required permanent bracing. 7 patients had pin tract infections. Infections healed in all patients.

Interpretation The Sheffield Ring Fixator gives an acceptable fusion rate for arthrodesis in the infected TKA, with limited complications.

Patients with a chronic or virulent deep knee infection that is resistant to antibiotic therapy, with extensive bone loss or severe systemic morbidities, can be unsuitable for revision arthroplasty. Knee fusion may be the only means of avoiding amputation (Conway et al. Citation2004, Leone and Hanssen Citation2005).

External fixation (XF), intramedullary nailing (IM) and dual plating have been used to achieve arthrodesis. IM is the commonest method used for non-septic cases (Wiedel Citation2002). IM in patients with deep joint infection carries the risk of dissemination, reactivation, or maintainance of a latent joint infection. XF minimizes this danger (Damron and McBeath Citation1995, Wiedel Citation2002). There have been no reports published on knee fusion patients with the Sheffield Ring Fixator after infected TKA. We therefore report the results of our first 10 patients to be operated with this technique.

Patients and methods

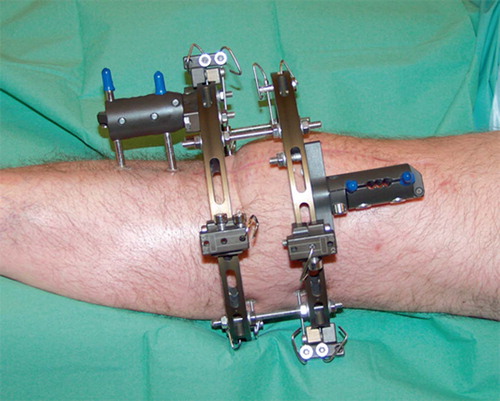

10 patients (5 men) with infected TKAs underwent knee arthrodesis with the Sheffield fixator in our department from 2001 to 2005 (). The patients were studied retrospectively. In 8 cases the reason for the TKA was primary arthrosis; 2 cases were due to rheumatoid arthritis and sclerodermia. Prior to arthrodesis, patients had been treated with oral or intravenous antibiotics (all 10), revision arthroplasty (1 patient), synovectomy (4 patients), or debridement (10 patients). 1 patient (case 3) was operated on for a traumatic patella fracture after insertion of the original TKA, which led to infection through a cicatricial defect and ultimately to destruction of the extensor apparatus.

Table 1. Patients

Arthrodesis was indicated because of ongoing virulent infection that was not responsive to antibiotic treatment and revision surgery, severely eroded paraarticular bone, destroyed extensor apparatus, unsuitability for or unwillingness to undergo repeated major surgery for anesthesiological and psychological reasons. The average age at the time of arthrodesis was 69 (61–81) years. All arthrodeses were performed by the same surgeon.

In 9/10 patients the arthrodesis with XF was performed in two stages. After debridement, the prosthesis was removed and replaced with a gentamicin spacer. Intravenous antibiotics were administered for 6–8 weeks. Biopsies for bacterial cultures were obtained and signs of infection observed. When the infection was quiescent, arthrodesis was performed.

Radiographic fusion was defined as trabecular bridging along the whole fusion area in both the anteroposterior () and lateral planes (Klinger et al. Citation2006). A clinically stable arthrodesis was the criterion for successful fusion. Clinical stability was evaluated after about 3 months by loosening the fixator bars, followed by weight bearing. If (1) the knee was stable and painless, if (2) radiographs showed no signs of callus formation or trabecularization, or if (3) infected pins caused loosening of the apparatus, the fixator was removed under anesthesia and stability was tested again. All patients underwent bandaging with a ROM splint (DonJoy, Vista, CA) or a custom-made stiff leather bandage for at least 4–6 weeks after removal. Pain was treated and pin tracts were inspected and cleaned daily. Pin tract infections (in 7 patients) were treated with dicloxacillin. Systemic antibiotics were administered 1 day after surgery, but cases 2, 3, and 9 were given intravenous antibiotics for a longer period (3, 7, and 19 days, respectively) due to elevated and initially sharply rising serum parameters indicating infection.

Figure 1. Anteroposterior radiograph showing trabecular fusion across the entire length of the arthrodesis.

Operative second-stage procedure

Access to the joint was through the former incision. The gentamicin spacer and eroded bone were removed. Debridement was performed. The bone ends were temporarily held with Steinmann pins. The fixator rings were connected by bars. Clamps were fixed to the centers of the diaphyseal femur and tibia with 2 hydroxyapatite-coated screws and bolted to a semicircular ring. Three 2-mm transosseous tensioned K-wires were fixed in the metaphyses and 1 additional cortical hydroxyapa-tite-coated screw connected the femoral bone with the proximal ring. The pins were removed. The arthrodesis was compressed with good bone contact and firmly stabilized at 5–10 degrees fiexion and 5–10 degrees valgus (). No bone graft was used. Full weight bearing was allowed as soon as possible. Further compression was applied after 6 weeks, when the fixator components were tightened.

Results

The average XF period was 3.2 (2–4) months. Fusion was achieved clinically at an average time of 3.6 (3–4) months and radiographically at mean

5.7 (3.5–10) months in 6 patients. All 10 patients started full weight bearing within 2 weeks. The average length of hospitalization was 2.9 (1–5) weeks. Of the 4 non-fusion patients, 2 had reduced knee compression due to loose femoral fixator pins in infected tracts (cases 2 and 8). The other 2 cases (cases 6 and 10) had the apparatus removed because of no signs of clinical and radiographic fusion, both after 3.5 months. 3 non-fused knees required permanent bracing, while 1 (case 2) was referred to another hospital for further treatment where IM was performed with fusion after 7 months. Case 8 was manodepressive and was unwilling to endure an extended period of fixation or further surgical treatment. Because of lacking signs of healing combined with severe systemic disease, fusion was thought to be unlikely to occur with the fixator in cases 6 and 10. Instead, it was hoped they might fuse with a brace. All patients had leg-length shortening; for the 7 legs measured it was mean 6 (1.5– 7.5) cm. All patients were available for monthly follow-up for an average of 9.9 (5.5–18) months, with additional radiographs at least 3 times postoperatively ().

Table 2. Results

No patients suffered skin or wound necrosis, neurovascular damage, or pin site fractures. All infections resolved. There were no subsequent femoral amputations. 7 patients had pin tract infection that was treated with oral dicloxacillin. The microorganisms present in the cultures from the first-stage operation are listed in .

Table 3. Results from perioperative biopsies during the first-stage operation

Discussion

External fixators offer the advantage of frame adjustment, thereby minimizing rotational forces and maximizing compression and stability at the arthrodesis—which allows early weight bearing, usually within a few days after surgery. Disadvantages are frame maintenance and encumbrance, later device removal, less predictable fusion rates, pin tract infections, pin loosening, risk of neurovascular damage during pin and wire insertion, and pin site stress fracture. Advantages of IM include high fusion rates, early weight bearing, and rapid mobilization. Disadvantages are long operation time, large perioperative blood loss, nail telescoping and breakage, potential rotational instability, perioperative fracture, bone marrow infection, and the fact that IM is technically challenging. Unless a short fusion nail is used, IM is hindered by an ipsilateral hip prosthesis while XF permits insertion of a hip prosthesis later on (Damron and McBeath Citation1995, Wiedel Citation2002, Conway et al. Citation2004, Domingo et al. Citation2004).

The external fixators were removed after approximately 3 months. We might have obtained more than 6 fused knees out of 10 attempts had the fixation period of the 4 nonunion patients been of a similar time range as in other XF studies, and if pin tract infections—with subsequent risk of pin loosening—had been avoided (Rand Citation1993) perhaps by administering peroral antibiotics for a relatively long period postoperatively. For the reasons stated, 3 of these patients were treated permanently with bracing. In infected TKAs, fusion rates with unior biplanar apparatuses and the multi-ring Ilizarov fixator spanned from one-third to nine-tenths and from two-thirds to all, respectively, in series with 4–29 patients and 2–19 patients (with considerable fixation periods varying from 2–10 months and 2–6 months) (Rothacker and Cabanela Citation1983, Knutson et al. Citation1985, Rand et al. 1987, Vlasak et al. Citation1995, Garberina et al. Citation2001, Manzotti et al. Citation2001, Vanryn and Verebelyi Citation2002, Conway et al. Citation2004, Klinger et al. Citation2006).

A meta-analysis of techniques used for knee arthrodesis after failed TKA, most of which were infected, reported overall fusion rates of 95% in patients treated with IM, compared with 64% for patients treated with XF (Damron and McBeath Citation1995). The authors recommended IM except for when the infection cannot be eradicated, in which case two-stage XF would be more appropriate. They stated that XF has been used more frequently in cases with Gram-negative or multimicrobial infections, but noted a significant increase in XF fusion rates where infections were caused by Gram-positive organisms.

Rand (Citation1993) reported 89 fusions out of 98 knee arthrodeses after failed TKAs with IM. It was stated that IM was the procedure of choice for non-septic failure of TKAs, or management of nonunion of an arthrodesis where there was remission of the infection. It was suggested that IM should be avoided in the presence of active infection due to the risk of introducing the infection into the bone marrow. This very serious complication was an important consideration in our choice of XF rather than IM.

Whether there is a significant difference in fusion rates for one- or two-stage XF is unclear because the selection criteria for knee arthrodesis vary between studies. Some authors suggest that staged XF should always be used in an attempt to eradicate multimicrobial or virulent infection where there is also extensive bone loss, and favor XF over IM and dual plating. Others advocate that a one-stage procedure is acceptable in the presence of Gram-positive infection without purulence. 7 of our 10 patients had pin tract infections, which is about the same as in other studies (Rand et al. Citation1986,Citation1987, Bengtson and Knutson Citation1991, Wiedel Citation2002, Conway et al. Citation2004, Leone and Hanssen Citation2005).

The femoral screws loosened in two non-fused knees, which may be explained by lower stability of the femoral ring relative to that of the tibial ring. The reason may be the narrower angles between the three K-wires compared to the tibia. Also, reduced bone quality in the femur compared to the tibia could possibly have delayed fusion in the 2 non-fusion patients with no infected tracts. Inferior femoral stability might be overcome and improved by applying an extra fixation bar, more femoral ring screws, or an additional proximal ring (Farrar et al. Citation2001). Also, secondary bone grafting, a prolonged fixation period, and further compression or callus distraction can be considered when signs of clinical and radiological fusion are not present (Knutson et al. Citation1985, Rand Citation1993).

Except for 1 case, we used a two-stage procedure. Other studies on treatment of deep infections in TKAs recommend opting for a one-stage procedure after adequate debridement (Bengtson and Knutson 1991, Conway et al. Citation2004, Leone and Hanssen Citation2005). We have found that the two-stage procedure is advisable when there is active virulent infection and severe bone loss.

Contributions of authors

AU: wrote the article. AU and KF: acquired and interpreted all relevant data. AU, KF, and LB: each contributed substantially to the conception and design of the study. LB: performed the surgery.

No competing interests declared.

- Bengtson S, Knutson K. The infected knee arthroplasty. A 6 year follow-up of 357 cases. Acta Orthop Scand 1991; 63: 301–11

- Conway J D, Mont M A, Bezwada H P. Arthrodesis of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2004; 86: 835–48

- Damron T A, McBeath A A. Arthrodesis following failed total knee arthroplasty. Comprehensive review and metaanalysis of recent literature. Orthop 1995; 18(4)361–8

- Domingo L J, Caballero M J, Cuenca J, Herrera A, Sola A, Herrero L. Knee arthrodesis with the Wichita fusion nail. Int Orthop 2004; 28: 25–7

- Farrar M, Yang L, Saleh M. The Sheffield hybrid fixator – a clinical and biomechanical review. Injury 2001; 32(Suppl 4)SD8–13

- Garberina M J, Fitch R D, Hoffmann E D, Hardaker W T, Vail T P, Scully S P. Knee arthrodesis with circular external fixation. Clin Orthop 2001, 382: 168–78

- Klinger H-M, Spahn G, Schultz W, Baums M H. Arthrodesis of the knee after failed infected total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2006; 14(5)447–53

- Knutson K, Lindstrand A, Lidgren L. Arthrodesis For Failed Knee Arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1985; 67(1)47–52

- Leone J M, Hanssen A D. Management of infection at the site of a total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2005; 87: 2335–48

- Manzotti A, Pullen C, Deromedis B, Catagni M A. Knee arthrodesis after infected total knee arthroplasty using the Ilizarov method. Clin Orthop 2001, 389: 143–9

- Rand J A. Alternatives to reimplantation for salvage of the total knee arthroplasty complicated by infection. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1993; 75: 282–7

- Rand J A, Bryan R S, Morrey B F, Westholm F. Management of infected total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop 1986, 205: 75–85

- Rand J A, Bryan R S, Chao E Y S. Failed total knee arthroplasty treated by arthrodesis of the knee using the Ace-Fisher apparatus. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1987; 69: 39–45

- Rothacker G W, Cabanela M E. External fixation for arthrodesis of the knee and ankle. Clin Orthop 1983, 180: 101–8

- VanRyn J S, Verebelyi D M. One-stage débridement and knee fusion for infected total knee arthroplasty using the hybrid frame. J Arthrop 2002; 17(1)129–34

- Vlasak R, Gearen P F, Petty W. Knee arthrodesis in the treatment of failed total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop 1995, 321: 138–44

- Wiedel J D. Salvage of infected total knee fusion: The last option. Clin Orthop 2002, 404: 139–42