Abstract

Background A standard ilioinguinal approach is often insufficient for reduction and stabilization of the medial acetabular wall and the dorsal column in acetabular fractures. To avoid extended approaches, we have used a medial extension of the approach by transverse splitting of the rectus abdominis muscle. We have thus been able to reduce and stabilize transverse and oblique fractures of the dorsal column and the medial acetabular wall and to fix plates in a mechanically better position below the pelvic brim. To evaluate the procedure, especially the risk of abdominal hernia, we started a prospective study.

Patients and methods Over 2 years, we treated 21 consecutive patients using a transverse splitting of the rectus abdominis muscle—either as an extension of the standard ilioinguinal approach or in combination with parts of this approach or a Kocher-Langenbeck approach. The patients were evaluated clinically and radiographically after 1 year.

Results The clinical and radiographic results were excellent or good in 18 patients. Complications occurred in 5 patients. No hernias were observed.

Conclusions Our small study indicates that the procedure described is a useful and safe complement to the intrapelvic approaches. The procedure does not provide better reduction than extended approaches, but may help to avoid them in some cases.

The use of extended approaches for open treatment of acetabular fractures is accompanied by a higher rate of blood loss, greater operation time, and more complications—and should be avoided whenever possible. The ilioinguinal approach by Letournel (Citation1961) produces a cosmetic scar, has a relatively short rehabilitation time, and has a low incidence of ectopic bone formation. However, in medially displaced fractures of the acetabulum below the pelvic brim and associated fractures of the dorsal column, reduction and stabilization are often difficult because the surgeon is working almost perpendicular to the direction of dislocation and plates can only be fixed above the pelvic brim. For these reasons, in special cases we extended the standard ilioinguinal approach to the medial by a transverse dissection of the rectus abdominis muscle. This extension provided good exposure of the medial acetabular wall and the dorsal column and plates could be fixed below the pelvic brim to achieve optimal stability. A longitudinal split of the rectus abdominis muscle in the linea alba has been described for the treatment of pelvic fractures (Cole and Bolhofner Citation1994, Ponsen et al. Citation2006). As the experience from general surgery is that transverse laparotomies have no increased rate of complications compared to vertical laparotomies, we started this prospective study to evaluate transverse splitting of the rectus abdominis muscle.

Patients and methods

Between January 2004 and December 2005, 21 consecutive patients with a mean age of 50 (23–76) (18 men) and with displaced acetabular fractures were treated by the first author using a transverse split of the rectus abdominis muscle—either as an extension of a full standard ilioinguinal approach or in combination with parts of this approach or a Kocher-Langenbeck approach. The average time between injury and operation was 5 (3–8) days. The fractures were classified according to the system of Judet et al. (Citation1964) (). In 15 patients we used a medially extended full standard ilioinguinal approach, and in 5 patients we used a combination including the second and third window of the ilioinguinal approach by encircling the iliac vessels. In 1 case we used a combination with a dorsal approach. Postoperatively, all patients wore compression stockings and received low-molecular-weight heparin until full weight bearing. The 1 patient with the additional dorsal approach received 3×50 mg indomethacin per day for 6 weeks. Physiotherapy started on the second postoperative day, with partial weight bearing of 20 kp on the extremity involved. Patients were taught to get out of bed in the same way as after an inguinal hernia operation. 6 weeks postoperatively, they were allowed to bear weight as tolerated. Pain, function, mobility, and the radiographic result were evaluated 11–14 months after the operation using the Merle d'Aubigne score as modified by Matta (Merle d'Aubigne and Postel Citation1951, Matta et al. Citation1986).

Table 1. Classification of acetabular fractures

Operative technique

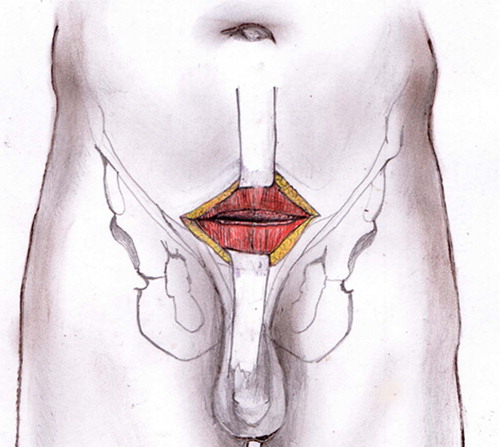

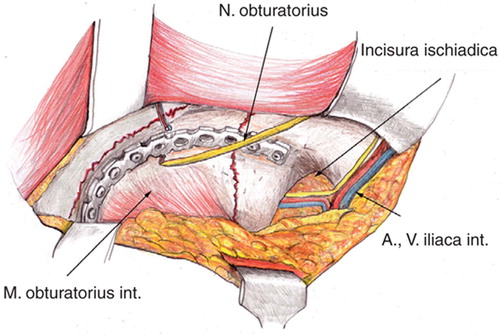

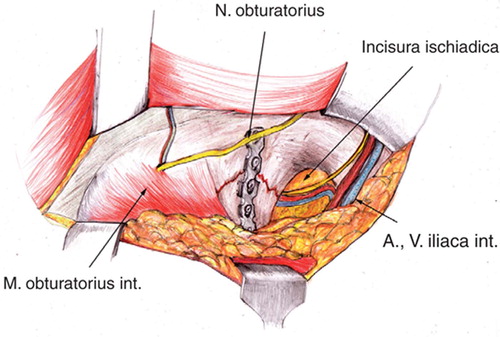

The patient was placed in supine position on a radiolucent table. The entire lower abdominal and pelvic region and the hindquarter on the affected side were prepared and draped. The lower extremity involved was draped free. The surgeon started the approach by being positioned on the fracture side and changed to the opposite side to work on the fracture. The standard ilioinguinal approach was performed as usual. The skin incision over the rectus abdominis muscle was a transverse one about two fingers above the symphysis. The fascia was split and the muscle was then dissected in the linea alba and a finger put in for blunt dissection of the prevesical space (). Lifting each side of the muscle with the finger on its dorsal side, the muscle was cut by electrocauterization. Vascular anastomoses on the pubic ramus were split between ligatures. The iliac vessels were retracted to the lateral and upwards. The psoas muscle fascia and the fascia of the internus obturatorius muscle were split along the pelvic brim and these muscles were elevated with the raspatory until the lower part of the iliac fossa, the whole medial acetabular wall, and the dorsal column down to the sciatic spine were exposed (). After full exposure, medial wall fragments were pushed medial to lateral with a spiked ball tip impactor. The posterior column could be elevated with a bone hook in the greater sciatic notch. Manual lateral traction of the femoral head was achieved by inserting a Schanz screw with a T-handle in the proximal femur. Definite fixation of medial wall fragments was achieved by spanning plates bridging from a stable sciatic buttress fragment anteriorly to the pubic ramus. These plates were fixed at the sciatric buttress first and contoured in a way that they pushed the medial wall to the lateral when the screws in the pubic ramus were tightened. Fractures of the posterior column could also be fixed with plates (). Reduction and positioning of hardware were controlled by intraoperative fluoroscopy. A separate posterior approach was used for fractures of the posterior wall. In this case, the anterior approach was done first. The wound was closed as usual in laparotomies by running monofilament resorbable loop suture. Fascia and muscle were taken with one stitch.

Results

Half of the fractures treated were associated types (). The injury severity score averaged 15 (9–32) points. The average time between injury and operation was 5 (3–8) days. The average operating time was 3.5 (2—4) h. Average intraoperative blood loss was 1 (0.5–2.6) L. All 15 patients without any other injuries that would hinder mobilization arose from bed on the second postoperative day. The clinical and radiographic outcome was good or excellent in most patients (). On the sixth week, a radiographic check in one incompliant patient with severe osteoporosis showed loss of reduction after full weight bearing that had occurred too early. The radiographic result and later clinical result were both classified as poor. There were complications in 5 patients. The iliac vein was perforated intraop-eratively in 1 case. The leak was sutured and had healed without thrombosis at the sixth-week postoperative ultrasound control. Deep-vein thrombosis developed in the femoral vein in 1 patient, and in the veins of the lower leg in another patient. 1 transient sciatic palsy occurred. In 1 patient, the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve was injured and did not recover. No cases of heterotopic ossification limiting the range of motion and no cases of intraarticular penetration of screws were observed.

Table 2. Clinical and radiographic results of 21 acetabular fractures

Discussion

Even with pharmacological and radiation prophylaxis, extrapelvic approaches—especially extended approaches—greatly increase the risk of heterotopic ossification and often result in postoperative loss of motion (Mears and Rubash Citation1983, Tile et al. Citation1992, Moed and Maxey Citation1993). In addition, rehabilitation is often delayed because of intraoperative trauma to the hip abductors. For these reasons, we try to use an intrapelvic approach whenever possible. On the other hand, a standard ilioingui-nal approach provides only limited exposure of the dorsal column and medial acetabular wall and positioning of plates is limited to the region above the pelvic brim. Thus, many fractures of similar type cannot be reduced and fixed well using a standard ilioinguinal approach. A medial intrapelvic approach provides nearly complete exposure of the medial acetabular wall and dorsal column down to the sciatic spine. With the surgeon standing on the opposite side from the apex of dislocation, the fragments can be reduced by pushing from medial to lateral. Bridging plates can be fixed below the pelvic brim in a biomechanically better position. This procedure requires a stable sciatic buttress fragment. In some cases, there is only room for 1 screw in this fragment. We then combine a 4.5-mm screw with a 3.5-mm titanium reconstruction plate with combined interlocking and normal holes into which the large screw fits. Putting the plate below the pelvic brim, one has to be careful not to impinge upon the obturatorius nerve below the pubic ramus. Fracture of the dorsal column can be reduced and also fixed with plates. Care has to be taken not to harm the lumbosacral trunk in the sciatic notch. The modified Stoppa approach has been used as a medial intrapelvic approach (Cole and Bolhofner Citation1994). The original Stoppa (Citation1989) approach was developed for hernia surgery. In its modified form, it is more or less a Pfannenstiel approach with transverse skin and fascia incision two fingers above the symphysis and median vertical dissection of the rectus abdominis muscle. The exposure and plating options are the same as described above (Cole et al. Citation1994). It can easily be extended into a standard ilioinguinal approach, but according to the authors and to our own experience one must dissect the muscle sharply at its distal insertion to expose the symphysis body and pubic ramus. This is functionally the same as a transverse split at the level of the skin incision. This dissection can only be avoided by using a long median vertical split of the linea alba up to the umbilicus, requiring a vertical skin incision. This is the original Stoppa approach and it has also been described for the treatment of acetabular and pelvic ring fractures (Ponsen et al. Citation2006). We have no experience of this approach.

Our own procedure of transverse split of the rectus abdominis muscle does not seem to be very elegant at first sight. It was first performed in single cases as an extension of the standard ilioinguinal approach, and showed good results. We know from our own experience of general surgery that transverse laparotomies do not have a higher complication rate than vertical ones and there is good evidence for this in the literature (Greenall et al. Citation1980, Ellis et al. Citation1984, Grantcharov and Rosenberg Citation2001, O'Dwyer and Courtney Citation2003). The operative technique is easy. The time that it takes is only slightly longer and it is not associated with increased blood loss. There does not appear to be any increase in early postoperative morbidity. We found no local complications, and no hernias. Contraindications for this approach are abdominal rigidity for any reason, fractures with pure posterior pathology, or sciatic buttress comminution. The technique described appears to be a useful complement to the intrapelvic approaches. It does not provide better reduction than the extended extrapelvic approaches but it may help to avoid these in some cases.

No competing interests declared.

Contributions of authors

JH developed the technique and operated on all patients. MA, WS developed the technique and were first assistance at all operations. SR, RG helped with the clinical and radio-graphic evaluation.

- Cole J D, Bolhofner B R. Acetabular fracture fixation via a modified Stoppa limited intrapelvic approach. Clin Orthop 1994, 305: 112–23

- Ellis H, Coleridge-Smith P D, Joyce A D. Abdominal incisions-vertical or transverse?. Postgrad Med J 1984; 6: 407–10

- Grantcharov T P, Rosenberg J. Vertical compared with transverse incisions in abdominal surgery. Eur J Surg 2001; 167: 260–7

- Greenall M J, Evans M, Pollock A V. Midline or transverse laparotomy? A random controlled clinical trial. Part 1. Influence on healing. Br J Surg 1980; 67: 188–90

- Judet R, Judet J, Letournel E. Fractures of the acetabulum: Classification and surgical approaches for open reduction. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1964; 46: 1615–46

- Letournel E. Les fractures du cotyle. Etude d'une serie de 75 cas. J Chir 1961; 82: 47–87

- Matta J M, Anderson L M, Epstein H C, Hendricks P I. Fractures of the acetabulum. A retrospective analysis. Clin Orthop 1986, 205: 230–40

- Mears D C, Rubash H E. Extensile exposure of the pelvis. Contemp Orthop 1983; 6: 21–30

- Merle d'Aubigne R, Postel M. Functional results of hip arthroplasty with acrylic prosthesis. J Boe Joint Surg (Am) 1951; 36: 451–60

- Moed B, Maxey J W. The effect of indomethazin on heterotopic ossification following acetabular fracture surgery. J Orthop Tauma 1993; 7: 33–8

- O'Dwyer P J, Courtney C A. Factors involved in abdominal wall closure and subsequent incisional hernia. Surg J R Coll Surg Edinb Irel 2003; 1: 17–22

- Ponsen K J, Joosse P, Schigt A, Goslings C, Luitse J. Internal fracture fixation using the Stoppa approach in pelvic ring and acetabular fractures: Technical aspects and operative results. J Tauma 2006; 61: 662–7

- Stoppa R E. The treatment of complicated groin and incisional hernias. World J Surg 1989; 13: 545–54

- Tile M, Helfet D L, Kellam J F, Letournel E, Matta J M. Symposium: Management of acetabular fractures. Part 2. Contemp Orthop 1992; 25: 389–94