Abstract

Background and purpose High tibial valgus osteotomy (HTO) is a well-accepted treatment for medial unicompartmental osteoarthritis of the knee with varus alignment in relatively young and active patients. Controversies about the factors affecting survival of HTO still exist. We assessed preoperative risk factors for failure of closing-wedge HTO at long-term follow-up.

Patients and methods A cohort of 100 patients with a mean age of 49 (24–67) years, who had closing-wedge HTO performed between January 1991 and December 1996, were analyzed retrospectively. A survival analysis was carried out according to the Kaplan-Meier method. Logistic regression analysis was used to assess the association between failure of the osteotomy and known potential preoperative risk factors.

Results The probability of survival for HTO was 75% (SD 4%) at 10 years with knee replacement as the endpoint. Female sex and osteoarthritis of grade ≥ 2 were identified as preoperative risk factors for conversion to arthroplasty 10 years after HTO.

Interpretation Our findings suggest that ideal candidates for corrective osteotomy are men with symptomatic medial compartmental osteoarthritis of Ahlbäck grade 1, who, 10 years after surgery, have an almost tenfold lower probability of failure of HTO than women with more advanced osteoarthritis.

High tibial valgus osteotomy (HTO) is a generally accepted treatment for medial unicompartmental osteoarthritis of the knee with varus alignment in active patients. Although successful osteotomy is effective in delaying the degenerative process, there is progressive deterioration and patients may require knee arthroplasty because of progression of symptoms (Virolainen et al. Citation2004).

Some studies have reported no clinical or radiographic difference in outcome for total knee arthroplasty (TKA) with or without a previous osteotomy (Staeheli et al. Citation1987, Meding et al. Citation2000), while others have reported substandard outcome of TKA after HTO (Katz et al. Citation1987, Nizard et al. Citation1998). Patient selection may be one of the reasons for this disparity, as young, heavy males with malalignment show a significantly higher prevalence of radiolucent lines and a higher revision rate after TKA. Also, technical difficulties must be dealt with when performing a TKA after HTO—with greater risk of complications than for a primary knee replacement without prior osteotomy (Parvizi et al. Citation2004). Thus, it is important to identify factors that predict good HTO survival.

Controversies about factors affecting survival of HTO still exist. Some studies have shown that success regarding the outcome of HTO may depend on the stage of osteoarthritis (Odenbring et al. Citation1990, Flecher et al. Citation2006). Other studies have recognized preoperative tibiofemoral alignment or more individual factors (such as age, sex, and obesity) to be predictors of patient dissatisfaction and conversion to arthroplasty (Coventry et al. Citation1993, Naudie et al. Citation1999, Huang et al. Citation2005).

The goal of the present study was to identify significant preoperative risk factors for failure of closing-wedge HTO at long-term follow-up.

Patients and methods

We retrospectively analyzed a cohort of 104 consecutive patients who had 108 closing-wedge HTOs, performed between January 1991 and December 1996. Patient records were reviewed, and patients or relatives of the patients who had died were interviewed by telephone to find out the postoperative status at the time of follow-up. Failure of the osteotomy was defined as conversion to a total knee arthroplasty. In 4 patients with staged bilateral procedures, only the first leg was included. 4 patients were lost to follow-up. 7 patients had died (10–11) years after the osteotomy, from an unrelated condition without their osteotomies being converted to a knee arthroplasty. The baseline characteristics of the 100 patients are shown in . The mean age at the time of surgery was 49 years (SD 11) there were 61 men. The average time of follow-up was 12 years (range 10–16 years). The grade of radiographic osteoarthritis was scored according to Ahlbäck (1968), and measured on standard short posteroanterior radiographs in standing position with the knee in full extension. The mechanical axis (hip-knee-ankle angle HKA) was measured on a whole-leg radiograph (WLR) in standing position. The patient stood barefoot on the affected leg with the knee in full extension, while the contralateral flexed knee was supported by means of a small box. The anteroposterior projection was ensured during lateral fluoroscopic control by superimposing the dorsal aspect of the femoral condyles. The tube was set perpendicular to this lateral view and was moved from the proximal end to the distal end, so that a WLR was obtained. We have previously reported high intra- and interobserver agreement in measurement of the HKA angle using this technique (Brouwer et al. Citation2003). All patients had varus malalignment of the knee with a mean preoperative HKA angle of 6.5° (SD 3.7°) of varus.

Baseline characteristics of the 100 patients at the time of closing-wedge osteotomy

A closing-wedge technique through a transverse incision with the patient in supine position was performed in all cases. Standard antibiotic prophylaxis was used. The common peroneal nerve was exposed and protected. Subsequently, the anterior part of the proximal fibular head (anterior part of the proximal tibia-fibular syndesmosis) was resected. We used a calibrated slotted wedge resection guide to remove the wedge size determined from the preoperative WLR, proximal to the patel-lar tendon insertion. The goal was to achieve a correction of 4° in excess of physiological valgus. The osteotomy was fixated with 2 step staples. At the end of the procedure, a fasciotomy of the anterior compartment was performed to prevent a compartment syndrome. After surgery, a standard cylinder plaster cast was applied for 6 weeks no standard anticoagulation was used. All patients were mobilized on the first postoperative day, and we allowed partial weight bearing with the use of 2 crutches for 6 weeks.

Adverse events related to the surgical technique

1 patient was reoperated because of overcorrec-tion (varus HTO), and another patient because of a symptomatic exostosis at the anterior site of the osteotomy. 3 patients had sensory peroneal neuropathy, but normal motor function. All osteotomies healed and no deep infections occurred. In 47 patients, the staples were removed because of local pain.

Statistics

SPSS statistical software version 10.1 was used for statistical analysis and a p-value of 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. A survival analysis was carried out according to Kaplan and Meier. We investigated the relation between conversion of HTO to a TKA and known potential pre-operative risk factors: i.e. age (Naudie et al. Citation1999), sex (Aglietti et al. Citation2003), body mass index (BMI) (Matthews et al. Citation1988), preoperative Ahlbäck grading (Flecher et al. Citation2006), and preoperative HKA angle < 9° of varus (Huang et al. Citation2005).

We calculated odds ratios by logistic regression analysis, to estimate the relationship between failure of the osteotomy and possible preoperative risk factors. We performed multivariate, stepwise (backward) logistic regression and entered variables with a p-value of ≤ 0.05 into the model.

Results

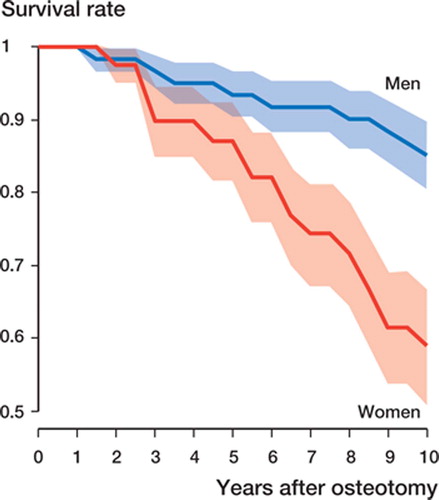

25 osteotomies had been revised to a TKA at the 10-year follow-up. The average time between the osteotomy and TKA was 6 (SD 3) years. The probability of survival for a closing-wedge HTO was 75% (SD 4%) at 10 years with knee replacement as the endpoint ().

Figure 1. Survival curve for 100 knees after HTO with TKA as the endpoint, at 10 years of follow-up.

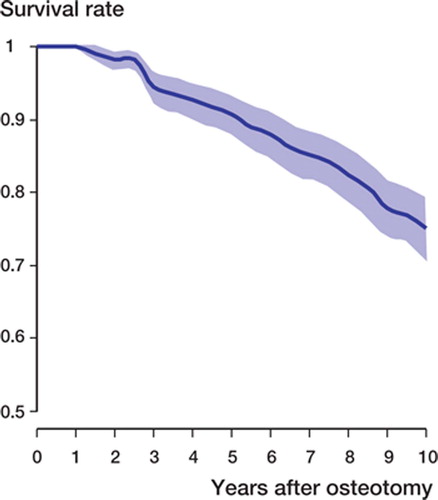

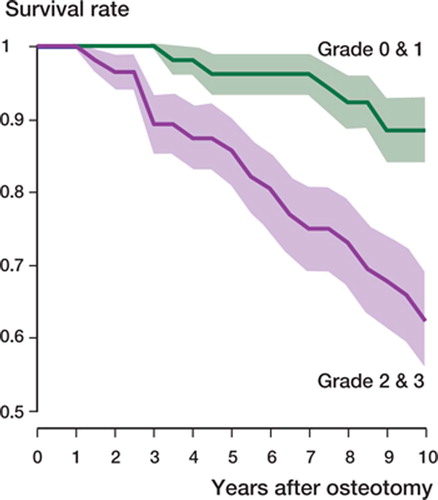

Using the logistic regression model, sex and osteoarthritis of Ahlbäck grade ≥ 2 were identified as preoperative risk factors for conversion to arthroplasty (p = 0.008 and p = 0.004, respectively) 10 years after HTO. There was a fourfold (95% CI: 1.4–11) higher risk of conversion to arthroplasty for women, and a fivefold (95% CI: 1.7–16) higher risk of knee replacement in patients with osteoarthritis of Ahlbäck grade ≥ 2. The probability of no failure for men was 85% while women had a probability of no failure of 59% 10 years after osteotomy (p = 0.003) (). If the preoperative Ahlbäck grade of osteoarthritis was ≥ 2, the probability of no failure at 10 years was 62%, as compared to a probability of 90% for Ahlbäck grade ≤ 1(p = 0.004) (). Age just failed to reach statistical significance (p = 0.06) as a risk factor for failure. There was no association between either BMI or the preoperative HKA angle and HTO failure. Men with Ahlbäck grade-1 osteoarthritis at baseline had the lowest risk of failure (6%) whereas women with Ahlbäck grade > 1 had the highest risk of failure (57%).

Figure 3. Survival curve for HTO with TKA as the endpoint, according to Ahlbäck's classification (Ahlbäck Citation1968).

Discussion

In our experience, active patients with radiographi-cally or arthroscopically confirmed symptomatic unicompartmental medial osteoarthritis of the knee and varus malalignment may be treated successfully with a correction osteotomy instead of arthroplasty. One Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register study found that young age was associated with an increased risk of prosthetic revision (Robertsson et al. Citation2001). The cumulative revision rate for unicompartmental arthroplasty (UKA) was even higher than for TKA. One of the technical problems after removal of UKA will be loss of bone stock. This requires significantly more osseous reconstructions in total knee revision compared to revision TKA after HTO (Gill et al. Citation1995). However, we have restricted HTO to patients with knee motion of more than 90° and with less than 15° of flexion contraction, without collateral laxity greater than the expected from the diminished joint space on physical examination, and with varus malalign-ment on a WLR of not more than 15°. Our findings in the present study—with 75% of patients at 10 years not requiring a TKA after HTO—compare well with other studies, which have corresponding figures ranging from 51% to 92% at 10 years (Coventry et al. Citation1993, Naudie et al. Citation1999, Sprenger et al. Citation2003, Flecher et al. Citation2006). Factors such as age, preoperative grade of osteoarthritis, sex, BMI, and preoperative angular deformity have been reported to influence HTO survivorship. We conducted this retrospective, long-term follow-up study to determine the effect of these factors on HTO survival, and to further define indications for osteotomy with the aim of improving our revision rate even more.

We used strict indications for performance of osteotomy, but our study was not prospective. The HTO procedure was also performed and supervised by different surgeons over the study period, in a teaching hospital setting. On the other hand, this represents common orthopedic practice. Another limitation might be that failure of HTO was only defined as conversion to a TKA. No knee scores or radiographs were used to measure knee function or grade of radiographic osteoarthritis at the time of follow-up. However, delaying or perhaps even avoiding knee replacement is one of the main reasons for performing HTO. Thus, it is useful to choose arthroplasty as the endpoint of HTO survival.

Previous studies have reported young patients, less than 50 years of age, to be appropriate candidates for HTO (Naudie et al. Citation1999, Flecher et al. Citation2006). We did not find age to be a risk factor for failure. Other studies agree with this and have found no influence of age on survival rate (Odenbring et al Citation1990, Sprenger et al. Citation2003, Huang et al. Citation2005, Spahn et al. Citation2006). This disparity in findings may be due to different distributions of patients in the study groups. Conversion of HTO to TKA is used as the endpoint of HTO failure in almost all survival analyses. A younger population will then have a favorable result because, irrespective of the clinical outcome, patients younger than 55 years of age are generally not considered to be suitable candidates for knee replacement. This could be the reason why—in our study—age just failed to reach statistical significance in the multivariate model.

TheAhlbäck scoring system of knee osteoarthritis is widely used, and is considered a valuable tool in surgical decision making. Recent reports have shown poor reproducibility and validity (Galli et al. Citation2003, Weidow et al. Citation2006). This might explain the existing controversy about the role of the severity of osteoarthritis in HTO survival. Huang et al. (Citation2005) found no correlation between severity of arthritis measured radiographically and clinical outcome. The authors attributed this to their strict indication for HTO: all knees were of Ahlbäck grade 3 or less preoperatively. We found that there was a strong correlation between preoperative stage of osteoarthritis and osteotomy failure. Odenbring et al. (Citation1990) also found that advanced stages of arthrosis increased the revision rate of osteotomy. Also, Flecher et al. (Citation2006) found that preoperative Ahlbäck grade 1 corresponded to a good outcome.

Although HTO with optimal correction gives pain relief, it does not appear to prevent the progression of medial arthrosis (Flecher et al. Citation2006). Radiographic progression of medial-compartment arthritis was observed by Stuart et al. (Citation1990) in four-fifths of patients 9 years after closing-wedge HTO. A recent meta-analysis has demonstrated sex differences in prevalence and incidence of osteoarthritis, with females at higher risk (Srikanth et al. Citation2005). Females also tended to have more severe osteoarthritis of the knee, particularly after menopausal age. Although some studies (Huang et al. Citation2005, Flecher et al. Citation2006) have not found sex to be an influencing factor, Aglietti et al. (Citation2003) noted superior results for men in an analysis of 120 closing-wedge HTOs at an average follow-up of 15 years. In our study, women also had poorer results at 10-year follow-up. Being overweight has been recognized as a significant factor for prediction of a poor outcome after HTO (Spahn et al. Citation2006). We found, however, that BMI had a minor role in comparison to the preoperative grade of osteoarthritis and the sex of the patient.

Large preoperative tibiofemoral varus malalign-ment has been described as a predictor of HTO failure and patient dissatisfaction after HTO (Huang et al. Citation2005). In our opinion, patients with a varus of more than 15° are not suitable for closing-wedge osteotomy. In our patients, probably due to the moderate mean preoperative 6.5° (SD 3.7°) of varus malalignment, we found no correlation between preoperative varus deformity and HTO failure. In a similar group of patients (with 6° of preoperative varus on average) Flecher et al. (Citation2006) found that there was no influence of the preoperative angle on outcome after osteotomy.

In summary, we found that the sex of the patient and the stage of osteoarthritis preoperatively were predictive of the survival of closing-wedge HTO. Men with medial compartmental osteoarthritis of Ahlbäck grade 1 had an almost tenfold lower probability of failure of HTO than women with higher grades of osteoarthritis.

No competing interests declared.

Contributions of authors

TR designed the study and drafted the manuscript. MR carried out the statistical analysis and was involved in interpretation of the data. RB and TJ contributed substantially to the acquisition of data. RB and JV participated in the study design and were involved in critically revising the manuscript.

- Aglietti P, Buzzi R, Vena L M, Baldini A, Mondaini A. High tibial valgus osteotomy for medial gonarthrosis: a 10- to 21-year study. J Knee Surg 2003; 16: 21–6

- Ahlbäck S. Osteoarthritis of the knee. A radiographic investigation. Acta Radiol Diagn (Suppl 277) 1968; 7–72

- Brouwer R W, Jakma T S C, Bierma-Zeinstra S M A, Ginai A Z, Verhaar J A N. The whole leg radiograph:stand-ing versus supine for determining axial alignment. Acta Orthop Scand 2003; 74: 565–8

- Coventry M B, Ilstrup D M, Wallrichs S L. Proximal tibial osteotomy: a critical long-term study of eighty-seven cases. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1993; 75: 196–201

- Flecher X, Parratte S, Aubaniac J-M, Argenson J-N A. A 12-28-year follow-up study of closing wedge high tibial osteotomy. Clin Orthop 2006, 452: 91–6

- Galli M, De Santis V, Tafuro L. Reliability of the Ahlbäck classification of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2003; 11(8)580–4

- Gill T, Schemitsch E H, Brick G W, Thornhill T S. Revision total knee arthroplasty after failed unicompartmental knee arthroplasty or high tibial osteotomy. Clin Orthop 1995, 321: 10–8

- Huang T, Tseng K, Chen W, Lin R M, Wu J, Chen T. Preoperative tibiofemoral angle predicts survival of proximal tibia osteotomy. Clin Orthop 2005, 432: 188–95

- Katz M M, Hungerford D S, Krackow K A, Lennox D W. Results of total knee arthroplasty after failed proximal tibial osteotomy for osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1987; 69(2)225–33

- Matthews L S, Goldstein S A, Malvitz T A, Katz B P, Kaufer H. Proximal tibial osteotomy, factors that influence the duration of satisfactory function. Clin Orthop 1988, 229: 193–200

- Meding J B, Keating E M, Ritter M A, Faris P M. Total knee arthroplasty after high tibial osteotomy. Clin Orthop 2000, 375: 175–84

- Naudie D, Bourne R B, Rorabeck C H, Bourne T J. Survivorship of the high tibial valgus osteotomy. a 10- to 12-year follow-up study. Clin Orthop 1999, 367: 18–27

- Nizard R S, Cardinne L, Bizot P, Witvoet J. Total knee replacement after failed tibial osteotomy. J Arthroplasty 1998; 13(8)847–53

- Odenbring S, Egund N, Knutson K, Lindstrand A, Toksvig Larsen S. Revision after osteotomy for gonartrosis. A 10 -19-year follow-up of 314 cases. Acta Orthop Scand 1990; 61(2)128–30

- Parvizi J, Hanssen A D, Spangehl M J. Total knee arthroplasty following proximal tibial osteotomy: risk factors for failure. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2004; 86(3)474–9

- Robertsson O, Knutson K, Lewold S, Lidgren L. The Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register 1975-1997. Acta Orthop Scand 2001; 72(5)503–13

- Spahn G. Kirschbaum S, Kahl E. Factors that influence high tibial osteotomy results in patients with medial gonar-thritis: a score to predict results. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2006; 14: 190–5

- Sprenger T R, Doerzbacher J F. Tibial osteotomy for the treatment of varus gonarthrosis. Survival and failure analysis to twenty-two years. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2003; 85: 469–74

- Srikanth VK, Fryer J L, Zhai G, Winzenberg T M, Hosmer D, Jones G. A meta-analysis of sex differences prevalence, incidence and severity of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2005; 13: 769–81

- Staeheli J W, Cass J R, Morrey B F. Condylar total knee arthroplasty after failed proximal tibial osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1987; 69(1)28–31

- Stuart M J, Grace J N, Ilstrup D M, Michael Kelly C, Adams R A, Morrey B F. Late recurrence of varus deformity after proximal tibial osteotomy. Clin Orthop 1990; 260 61–5

- Virolainen P, Aro H T. High tibial osteotomy for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: a review of the literature and a meta-analysis of follow-up studies. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2004; 124: 258–61

- Weidow J, Cederlund C-G, Ranstam J, Kärrholm J. Ahlbäck grading of osteoarthritis of the knee. Poor reproducibility and validity based on visual inspection of the joint. Acta Orthop 2006; 77(2)262–6