Abstract

Background and purpose Symptomatic treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee with leeches is presently undergoing a renaissance. Previous studies have shown methodical weaknesses. In the present study patients were blinded regarding the treatment, and a control group was included to explore possible differences in various subjective clinical scores and intake of pain medication over time between leech therapy and placebo control.

Patients and methods 113 patients with advanced osteoarthritis of the knee were included. The patients were randomized to a single treatment group, group I (single leech application, n = 38), a double treatment group, group II (double application, n = 35), and a control group (n = 40). The second treatment in group II took place after an interval of 4 weeks. The treatment in the control group was simulated with the help of an “artificial leech”. Results were documented with the KOOS and WOMAC scores and also a visual analog scale (VAS) for pain. Changes in the use of pain medication were monitored over 26 weeks.

Results An improvement in KOOS and WOMAC scores, and also in VAS, was found in all 3 groups following treatment. These improvements were statistically significant for treatment groups I and II during the complete follow-up period. The reduction in individual requirements for pain medication was also statistically significant. The greatest improvement was seen in the group treated twice with the leeches, with a long-term reduction of joint stiffness and improved function in the activities of daily living.

Interpretation Leech therapy can reduce symptoms caused by osteoarthritis. Repeated use of the leeches appears to improve the long-term results. We have not determined whether the positive outcome of the leech therapy is caused by active substances released during the leeching, the placebo effect, or the high expectations placed on this unusual treatment form.

The use of leeches (Hirudo medicinalis) has been popular throughout the ages, and still has a place in modern medicine—especially in reconstructive and microvascular surgery (Hayden et al. Citation1988, Dabb et al. Citation1992, Weinfeld et al. Citation2000, Rao and Whitaker Citation2003, Whitaker et al. Citation2004a, Citationb, Hyson Citation2005). The commonly used treatment for pain associated with osteoarthritis—non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)—is frequently associated with undesirable side effects; thus, in the search for alternative forms of treatment, leeching has received renewed interest (Hernandez-Diaz and Garcia-Rodriguez Citation2001, Pilcher Citation2004, Hernandez-Diaz et al. Citation2006). Michalsen and his group (Citation2002) have investigated the use of this traditional approach for the treatment of knee osteoarthritis in a clinical setting and compared its effectiveness to that of conventional therapy. The study was quoted in Nature in 2004 (Pilcher Citation2004). In a controlled non-randomized study from 2002, 16 patients were either treated with leeches or with a conventional protocol consisting of physiotherapy and health education (Michalsen et al. Citation2002). The treatment group (n = 10) with periarticular leech application showed a reduction of symptoms compared to the control group (n = 6). This encouraged the group to carry out a controlled randomized study involving 51 patients, who were evaluated over a 12-week period (Michalsen et al. Citation2003). The control group (n = 27) applied diclofenac gel twice daily to the affected knee over a 28-day period. By WOMAC score, there was significant reduction in pain and stiffness, and also improvement in function, in the leech group compared to the controls. The authors concluded that the traditional leech therapy represents an effective symptomatic treatment for osteoarthritis of the knee, while pointing out the preliminary character of their pilot study.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All previous studies and the authors' interpretations of the results must be reviewed critically. Validation of results is only possible if randomization and blinding of the patients has been undertaken (Guyatt et al. Citation1993, Hochberg Citation2003). In both of the reports cited, the patients were either allowed to choose their treatment form or were informed about the procedure they were to undergo. This can lead to bias of both the patient and the examiner. The influence of a placebo effect due to the lack of blinding causes further problems in the interpretation of results. As Wolfe and Lane (Citation2002) and Hochberg (Citation2003) have pointed out, a 7-day interval of pain reduction is a very short period compared to the time involved in the onset of osteoarthritis. The guidelines of the Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) recommend longer time frames (Altman et al. Citation1996, Hochberg et al. Citation1997).

Previous studies have not addressed the question of whether repeated leeching can supply symptomatic relief of osteoarthritic pain for extended periods of time. We present a randomized study designed to investigate possible differences in various clinical parameters of single and repeated leech therapy in cases with advanced osteoarthritis of the knee, using 2 large groups of patients and a control group of comparable size. All patients were blinded regarding treatment modality.

Patients and methods

Selection of patients and study design

This study was carried out at the Department of Orthopaedics of the University Hospital in Aachen, Germany in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, from February to December 2004. After permission was granted by the ethics board (EK 102/03), patients were recruited using the local daily newspapers. Screening was first carried out by telephone, based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria (). The patients included in the preliminary protocol underwent AP and lateral radiographs of the affected knee to verify the osteoarthritis. Once an outline of the study had been prepared and informed consent had been obtained, the patients who qualified for the study were randomized into a treatment (i.e. leech therapy) group (T) and a control group (C) using a 2-stage stratified randomization procedure.

Randomization

In the first step, patients were assigned randomly to either the T group of the C group based on a 2:1 randomization scheme. Twice as many patients were allocated to the T group than to the C group, as the treatment group was to be divided further in the second stage of the randomization procedure.

In the second step, all patients randomized to T group were further separated into groups with single (T1) or double (T2) application of the leech therapy, depending on the baseline values of their KOOS score. Patients with a KOOS baseline score above the median KOOS baseline score were allocated to T1, and all remaining patients of the treatment group were allocated to T2. For details of the randomization process, see Supplementary Data.

Patients

After initial telephone screening, 202 patients were invited to further evaluation. A total of 118 patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria. The randomization protocol allocated 77 patients to the treatment groups, while 41 served as controls. The stratification of the leech therapy group led to placement of 39 patients in T1, while 38 underwent 2 separate leech treatments (T2). 5 patients in total were not available for further examination after the initial treatment (C: n = 1; T1: n = 1; T2: n = 3) and they were therefore excluded from the evaluation. The data from the remaining 113 patients (C: n = 40; T1: n = 38; T2: n = 35) were analysed. For demographic data for the whole population, see .

Treatment protocol

All patients were informed explicitly during the consent procedure that for both the single and double application, randomization between the leeching and the placebo treatment would take place without their knowledge. Their view of the treated knee was obstructed with a blind before the treatment. The skin at the treatment site was cleaned with NaCl solution prior to the application of 4 leeches (Animalpharma GmbH, Weismain, Germany). 2 leeches were placed proximal to the patella and 1 each at the medial and lateral joint line, while the knee was placed comfortably in extension. The leeches were not removed by the examiner but remained in place until the leeching ended spontaneously after 50-60 min. A compres-sive dressing was applied for 24 h and the patients were requested to restrict their activity for 12 h. The second leeching of part of the study population (T2) was performed in an identical manner 4 weeks later.

Preparation and positioning of the patients in the control group was carried out as described above. The bite of the leech was simulated with a needle prick at the predetermined sites. To obtain a real istic effect in the region of skin contact, wet gauze was formed to resemble the size and form of a leech and placed at the site. After a “treatment” of 50-60 min, the “artificial leech” was removed and the protocol of the treatment groups was followed.

Table 2. Patient demographics

Evaluation

Follow-up evaluations were performed after 1, 4, and 6 weeks, and also after 3 and 6 months. Further visits were possible if problems arose. At the beginning of the study and at all follow-up examinations, patients answered questionnaires for the determination of KOOS and WOMAC. The questionnaires also included VAS and documentation of the intake of pain medication. As part of the follow-up visits, a clinical examination of the knee was carried out and the histories were updated.

Statistics

Adverse events and reactions were documented and presented in terms of absolute and relative frequencies. For all patients in the study groups, demographic data of categorical variables were summarized with absolute and corresponding relative frequencies, while arithmetic mean and corresponding standard deviation were used for continuous variables. For the three scores KOOS (Roos et al. Citation1998), WOMAC (Bellamy et al. Citation1988, Roos et al. Citation1999), and VAS (0 representing no pain and 10 the worst possible pain), and also for pain medication, data collected in the three study groups (C, T1, and T2) were condensed as median (m), lower quartile (25% quantile, Q25), and upper quartile (75% quartile, Q75) at 6 different time points (at the start of therapy, after 1, 4, and 6 weeks, and after 3 and 6 months). For the pain medication requirement, the baseline value of a patient was set to 100%. For the 5 time points after therapy, the corresponding relative changes (in per cent) in comparison to the baseline value were calculated.

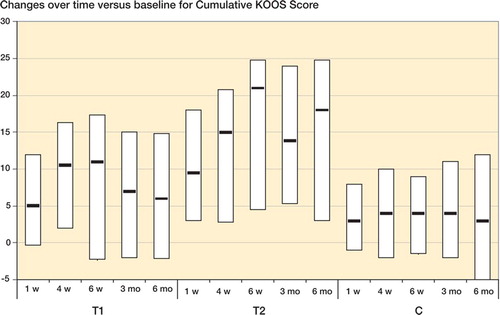

To allow better comparison of the 3 study groups, for each patient we calculated differences in the observed values of the 3 cumulative scores (KOOS, WOMAC, VAS) and subscores at the 5 time points after therapy relative to the corresponding baseline values. Once again, these differences were summarized as median, lower and upper quartile, separately for all groups.

Within each of the 3 groups, paired Wilcoxon tests were conducted in order to investigate whether the 3 total scores, the subscores, and also the requirement for pain medication at the 5 time points after therapy had changed statistically significantly as compared to the corresponding baseline values. Finally, the computed differences (different time points after therapy vs. start of therapy) were compared between the 3 study groups in pairwise fashion by means of unpaired Wilcoxon tests.

The global significance level for all statistical test procedures conducted was chosen to be a = 5%. As this was an explorative study, no a-adjustment for multiple testing was carried out. Thus, p-values of p ≤ 0.05 could be interpreted as being indicative of statistically significant test results with respect to the study cohort investigated.

All statistical analyses were conducted using the statistical analysis software system R (www.R.-project.org).

The data regarding median scores and quartiles at follow-up visits are not presented here, but are available in Supplementary data.

Results

The patients who underwent the leech therapy either once or twice showed a significant improvement compared to the baseline values in both the KOOS and WOMAC cumulative scores at all follow-up examinations (except for “Stiffness“ in group T1 after 1 and 6 weeks). The control population also had a significantly improved KOOS score at all follow-up occasions, while the WOMAC cumulative score showed significant improvement over time except at the 1-week and 6-month follow-up examinations. Subjective pain intensity (VAS) became significantly reduced during the whole observation period in all groups. A statistically significant reduction in pain medication requirement compared to the baseline values was seen in the 2 groups that underwent leech treatment, at all follow-up visits. Consumption of medication remained unaltered in the control group (). The Figure shows changes over time (medians and quartiles) for the cumulative KOOS score of the individual groups.

Table 3. Changes over time of p-values determined with the paired Wilcoxon test for the individual populations

The cumulative KOOS score of T2 was significantly improved throughout the observation period as compared to the controls. No significant differences between T1 and C were documented during the study. With the exception of the 4-week follow-up, at all other examinations comparison of T2 with T1 showed a significant improvement associated with the second leeching ().

The cumulative WOMAC score was significantly improved for the T2 population compared to the controls over the whole observation period. The T1 score was also significantly better than that of the controls up to the sixth week after the leech treatment. Later than that, no significant differences were found.

After single and double leech therapy, perceived pain—as documented in the KOOS and WOMAC pain scores—was significantly improved compared to the control group throughout the 6 months of follow-up. There was no apparent difference between T1 and T2. By VAS, continuous reduction of pain was measured at a statistically significant level for T2 patients through the study period. Improvement in pain for T1 was only significant after 6 weeks compared to the control group.

Joint stiffness, documented as part of the WOMAC score, showed a statistically significant improvement for the T2 group compared to the C group—and also, with the exception of the 4-week follow-up examination, in comparison to the T1 group. There was no significant difference between the T1 and C groups in this regard. Function (WOMAC) and ADLs (KOOS) were significantly improved for patients in the T2 group in all evaluation periods as compared to the control group. No other statistically significant parameters or differences were found.

The other parameters recorded in the KOOS score (not presented) showed statistically significant differences between T2 and C until the end of the 6-week evaluation period. No other significant differences were found. The evaluation showed statistically significant reductions in intake of pain medication for the treatment groups but not for the control group throughout the study period.

Table 4. Evaluation of the differences obtained for various parameters over time, expressed as p-values, determined with the unpaired Wilcoxon-test for comparison of the individual populations

At the end of the study, all participants were asked about the kind of treatment they thought they had received. 17/40 patients in the control group were convinced that they had received the placebo leeching. The corresponding numbers for T1 and T2 were 2/38 and 1/35, respectively. 8 control patients thought that they had been treated with leeches. The corresponding figures for T1 and T2 were 23/38 and 28/35, respectively. The remaining 15 patients in the control group were unsure about the form of treatment. The corresponding figures for T1 and T2 were 13/38 and 6/35.

Adverse effects

The leech therapy did not lead to any adverse effects or local complications in 34 patients. The remaining cases (n = 39) developed a local irritation at the site of application, with moderate itching. These symptoms had receded in all individuals by the follow-up evaluation at 4 weeks, and healed completely in all cases. Bleeding from the site of application was seen in 2 patients and was easily managed with compressive dressings. No other complications or infections were noted. There were no local complications after artificial leeching.

Discussion

Blinding of the patients as to the actual form of treatment in our study was an attempt to compensate for placebo effects. We found an improvement in knee symptoms following the single or repeated leech therapy using validated scores, but also a subjective benefit in the control group. To differentiate any placebo effect from the effect of leeching, we expressed our findings as the differences between follow-up and baseline scores at defined time periods. The values determined were then used to compare the treatment and the control groups. The method chosen to split the treatment population with the help of their baseline scores made this evaluation tool especially helpful. The comparison with the control group revealed that the second leeching after an interval of 4 weeks led to a better long-term effect on the knees in regard to pain reduction, improved function and ADLs, although the baseline symptoms and baseline scores of the osteoarthritis were more pronounced in this group (T2). The single leech therapy did not provide similar results throughout the study period.

Nearly two-thirds of the patients in the T1 group and four-fifths in T2 were able to correctly identify the form of treatment they had received, and only one fifth of the control group thought a leech had been applied. This means that the local effects of the leeching, such as the feeling from the bite, itching, or oozing played an important role in what the patients perceived. Even with the blinding of the patients, the artificial leech was not able to simulate the real leech therapy completely. Thus, even with the use of a control group, it remains impossible to clearly differentiate whether the positive effects seen in groups T1 and T2 were caused by substances in the leech saliva, the treatment procedure itself, or by a placebo effect.

The critical analysis of previous publications of leech therapy provided by Hochberg (Citation2003) has led to higher demands being placed on the design of follow-up studies. In addition, the reports published by Wolfe and Lane (Citation2002), as well as the recommendations of the Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) (Hochberg et al. Citation1997) have led to the requirement for a minimum 12-week (and ideally a 24-week) evaluation period to analyze the effectiveness of symptomatic therapy. Hochberg also reviewed the use of the WOMAC score critically. By adding further scores such as the internationally accepted knee-specific KOOS score (Kessler et al. Citation2003, Englund and Lohman-der Citation2005, Lahav et al. Citation2006), we have attempted to adhere to Hochberg's recommendations in our study design.

There is still no definitive explanation for the pain-reducing effect of leech therapy, and so leeching remains a constant source of debate. Several substances in the saliva of leeches are known to have a therapeutic effect. Pharmacologically active substances such as the thrombin-inhibiting and factor-Xa-inhibiting hirudin, as well histamine-like vasodilators, kallikrein- and tryptase-inhibitors, several other inhibitors of proteases and anesthetics have been isolated (Brown et al. Citation1980, Markwardt et al. Citation1982, Ascenzi et al. Citation1995, Hochberg Citation2003, Michalsen et al. Citation2003, Dippenaar et al. Citation2006). The spread into deeper tissue and the joint cavity may be made possible by hyaluronidase, but it remains unclear whether or not these substrates reach the synovial membrane or the synovia, and what effect they may have on the cartilage and subchondral bone (Michalsen et al. Citation2003). Hochberg (Citation2003) expressed doubt that the mechanism described above is an adequate explanation for the pain relief seen following leeching—in part due to the data presented by Rigbi et al. (Citation1987). Bush et al. (Citation1998) and Scott (Citation2002) pointed out that along with the capacity to inhibit thrombin, hirudin also inhibits the synovial stimulatory protein (SSP/DING)—a growth factor for synovial fibroblasts— while possessing anti-inflammatory properties. It may also be possible that the local analgesic, blood thinning, and anti-inflammatory components are enhanced by the indirect effect of a prolonged isolated bloodletting. This can only be clarified by testing each individual component of leech saliva.

The additional demand for pain medication was reduced significantly in both treatment groups, which may make leech therapy an attractive alternative. The patients must, of course, be informed about the side effects associated with leech treatment that have been described in the literature (Lineaweaver et al. Citation1992, De Chalain et al. Citation1996, Fennolar et al. Citation1999, Ikizceli et al. Citation2005), as well as the fact that the leech bite itself can lead to complications. Even in light of the positive clinical data in the treatment of osteoarthritis, leeching cannot be considered to be a completely harmless and safe procedure. To avoid leech-associated complications, inclusion and exclusion criteria must be strictly adhered to.

Our blinded and controlled explorative study has highlighted the effectiveness of leech therapy in the symptomatic treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. In contrast to previous studies, the repeated leeching led to a better long-term effect. The question regarding the ideal interval between two leechings remains unanswered. In future studies, it would be helpful to create a “repeated artificial leeching group” to better compare with repeated leeching. Improvement of the artificial leech should be attempted to increase the value of the control group. Nevertheless, because of our clinical results and the published positive effects, we believe that leech therapy could have a place as an additional symptomatic treatment modality for osteoarthritis. The indication for leech therapy might be in case of failure of the conventional nonoperative and surgical treatment modalities, or after consideration of existing contraindications. The clinical value of the leech therapy for osteoarthritis must be tested further in comparative studies involving the more classic forms of pain management, such as peroral NSAIDs.

No competing interests declared.

Contributions of authors

SA and US conceived and led the investigation. SS developed the study protocol and guided the statistical analyses. FS and UM performed the initial acquisition of data. CHS, TM, and RMR assisted with the study, in interpretation of results, and drafting of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

The study was supported by the Deutsche Arthrosehilfe. This did not influence the acquisition or analysis of data presented in this paper.

Supplementary data

A detailed description of the randomization process, the flowchart and evaluation data, the changes over time, and the differences obtained for various parameters over time (expressed as descriptive data and p-values determined with the paired/unpaired Wilcoxon-test for the individual groups) can be found on the Acta Orthopaedica website at www. actaorthop.org, identification number 0801.

- Altman R, Brandt K, Hochberg M, Moskowitz R, Bellamy N, Bloch D A, Buckwalter J, Dougados M, Ehrlich G, Lequesne M, Lohmander S, Murphy W A, Jr, Rosario-Jansen T, Schwartz B, Trippel S. Design and conduct of clinical trials in patients with osteoarthritis: recommendations from a task force of the Osteoarthritis Research Society. Results from a workshop. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 1996; 4: 217–43

- Ascenzi P, Amiconi G, Bode W, Bolognesi M, Coletta M, Menegatti E. Proteinase inhibitors from the European medicinal leech Hirudo medicinalis: structural, functional and biomedical aspects. Mol Aspects Med 1995; 16: 215–313

- Bellamy N, Buchanan W W, Goldsmith CH, Campbell J, Stitt L W. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol 1988; 15: 1833–40

- Brown J E, Baugh R F, Hougie C. The inhibition of the intrinsic generation of activated factor X by heparin and hirudin. Thromb Res 1980; 17: 267–72

- Bush D, Fritz H, Knight C, Mount J, Scott K. A hirudin-sensitive, growth-related proteinase from human fibroblasts. Biol Chem 1998; 379: 225–9

- Dabb R W, Malone J M, Leverett L C. The use of medicinal leeches in the salvage of flaps with venous congestion. Ann Plast Surg 1992; 29: 250–6

- De Chalain T M. Exploring the use of the medicinal leech: a clinical risk-benefit analysis. J Reconstr Microsurg 1996; 12: 165–72

- Dippenaar R, Smith J, Goussard P, Walters E. Meningococcal purpura fulminans treated with medicinal leeches. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2006; 7: 476–8

- Englund M, Lohmander L S. Patellofemoral osteoarthritis coexistent with tibiofemoral osteoarthritis in a meniscectomy population. Ann Rheum Dis 2005; 64: 1721–6

- Fenollar F, Fournier P E, Legre R. Unusual case of Aeromonas sobria cellulitis associated with the use of leeches. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 1999; 18: 72–3

- Guyatt G H, Sackett D L, Cook D J. Users' guides to the medical literature. II. How to use an article about therapy or prevention. A. Are the results of the study valid? Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA 1993; 270: 2598–601

- Hayden R E, Phillips J G, McLear P W. Leeches. Objective monitoring of altered perfusion in congested flaps. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1988; 114: 1395–9

- Hernandez-Diaz S, Garcia-Rodriguez L A. Epidemiologic assessment of the safety of conventional nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Am J Med (Suppl 3A) 2001; 110: 20S–7S

- Hernandez-Diaz S, Varas-Lorenzo C, Garcia Rodriguez L A. Non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs and the risk of acute myocardial infarction. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2006; 98: 266–74

- Hochberg M C. Multidisciplinary integrative approach to treating knee pain in patients with osteoarthritis. Ann Intern Med 2003; 139: 781–3

- Hochberg M C, Altman R D, Brandt K D, Moskowitz R W. Design and conduct of clinical trials in osteoarthritis: preliminary recommendations from a task force of the Osteoarthritis Research Society. J Rheumatol 1997; 24: 792–4

- Hyson J M. Leech therapy: a history. J Hist Dent 2005; 53: 25–7

- Ikizceli I, Avsarogullari L, Sozuer E, Yurumez Y, Akdur O. Bleeding due to a medicinal leech bite. Emerg Med J 2005; 22: 458–60

- Kessler S, Lang S, Puhl W, Stove J. The Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score-—a multifunctional questionnaire to measure outcome in knee arthroplasty. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb 2003; 141: 277–82

- Lahav A, Burks R T, Greis P E, Chapman A W, Ford G M, Fink B P. Clinical outcomes following osteochondral autologous transplantation (OATS). J Knee Surg 2006; 19: 169–73

- Lineaweaver W C, Hill M K, Buncke G M, Follansbee S, Buncke H J, Wong R K, Manders E K, Grotting J C, Anthony J, Mathes S J. Aeromonas hydrophila infections following use of medicinal leeches in replantation and flap surgery. Ann Plast Surg 1992; 29: 238–44

- Markwardt F, Hauptmann J, Nowak G, Klessen C, Walsmann P. Pharmacological studies on the antithrombotic action of hirudin in experimental animals. Thromb Haemost 1982; 47: 226–9

- Michalsen A, Moebus S, Spahn G, Esch T, Langhorst J, Dobos G J. Leech therapy for symptomatic treatment of knee osteoarthritis: results and implications of a pilot study. Altern Ther Health Med 2002; 8: 84–8

- Michalsen A, Klotz S, Ludtke R, Moebus S, Spahn G, Dobos G J. Effectiveness of leech therapy in osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2003; 139: 724–30

- Pilcher H. Medicinal leeches: stuck on you. Nature 2004; 432: 10–1

- Rao J, Whitaker I S. Use of Hirudo medicinalis by maxillo-facial surgical units in the United Kingdom: current views and practice. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2003; 41: 54–5

- Rigbi M, Levy H, Eldor A, Iraqi F, Teitelbaum M, Orevi M, Horovitz A, Galun R. The saliva of the medicinal leech Hirudo medicinalis. II. Inhibition of platelet aggregation and of leukocyte activity and examination of reputed anaesthetic effects. Comp Biochem Physiol C 1987; 88: 95–8

- Roos E M, Roos H P, Lohmander L S, Ekdahl C, Beynnon BD. Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS)—development of a self-administered outcome measure. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 1998; 28: 88–96

- Roos E M, Klassbo M, Lohmander L S. WOMAC osteoarthritis index. Reliability, validity, and responsiveness in patients with arthroscopically assessed osteoarthritis. Western Ontario and MacMaster Universities. Scand J Rheumatol 1999; 28: 210–5

- Scott K. Is hirudin a potential therapeutic agent for arthritis? Ann Rheum Dis 2002; 61: 561–2

- Weinfeld A B, Yuksel E, Boutros S, Gura D H, Akyurek M, Friedman J D. Clinical and scientific considerations in leech therapy for the management of acute venous congestion: an updated review. Ann Plast Surg 2000; 45: 207–12

- Whitaker I S, Izadi D, Oliver D W, Monteath G, Butler P E. Hirudo Medicinalis and the plastic surgeon. Br J Plast Surg 2004a; 57: 348–53

- Whitaker I S, Rao J, Izadi D, Butler P E. Historical Article: Hirudo medicinalis: ancient origins of, and trends in the use of medicinal leeches throughout history. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2004b; 42: 133–7

- Wolfe F, Lane N E. The longterm outcome of osteoarthritis: rates and predictors of joint space narrowing in symptomatic patients with knee osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol 2002; 29: 139–46