Abstract

Background and purpose — The use of uncemented revision stems is an established option in 2-stage procedures in patients with periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) after total hip arthroplasty (THA). However, in 1-stage procedures, they are still rarely used. There are still no detailed data on radiological outcome after uncemented 1-stage revisions. We assessed (1) the clinical outcome, including reoperation due to persistent infection and any other reoperation, and (2) the radiological outcome after 1- and 2-stage revision, using an uncemented stem.

Patients and methods — Between January 1993 and December 2012, an uncemented revision stem was used in 81 THAs revised for PJI. Patients were treated with 1- or 2-stage procedures according to a well-defined algorithm (1-stage: n = 28; 2-stage: n = 53). All hips had a clinical and radiological follow-up. Outcome parameters were eradication of infection, re-revision of the stem, and radiological changes. Survival was calculated using Kaplan-Meier analysis. Radiographs were analyzed for bone restoration and signs of loosening. The mean clinical follow-up time was 7 (2–15) years.

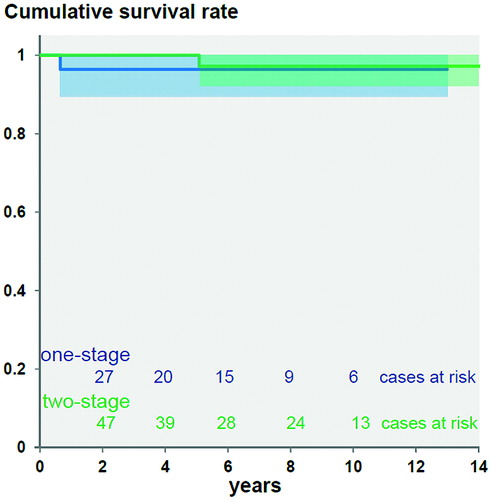

Results — The 7-year infection-free survival was 96% (95% CI: 92–100), 100% for 1-stage revision and 94% for 2-stage revision (95% CI: 87–100) (p = 0.2). The 7-year survival for aseptic loosening of the stem was 97% (95% CI: 93–100), 97% for 1-stage revision (95% CI: 90–100) and 97% for 2-stage revision (95% CI: 92–100) (p = 0.3). No further infection or aseptic loosening occurred later than 7 years postoperatively. The radiographic results were similar for 1- and 2-stage procedures.

Interpretation — Surgical management of PJI with stratification to 1- or 2-stage exchange according to a well-defined algorithm combined with antibiotic treatment allows the safe use of uncemented revision stems. Eradication of infection can be achieved in most cases, and medium- and long-term results appear to be comparable to those for revisions for aseptic loosening.

Periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) is a major complication after total hip arthroplasty (THA), causing additional surgery, impaired function, and high costs (Boettner et al. Citation2011, Kurtz et al. Citation2012). The incidence of PJI is rising due to the growing number of joint replacements performed, a steadily increasing population with arthroplasties (with a lifelong risk of hematogenous PJI), and increased surgical awareness in diagnosing PJI—with better diagnostic tools (Dale et al. Citation2012, Kurtz et al. Citation2012).

Successful management of PJI includes elimination of all microorganisms to give a pain-free joint with good function. Various surgical options are available to achieve this aim (Zimmerli et al. Citation2004). 2-stage exchange is traditionally the most frequently performed procedure (Osmon et al. Citation2013). However, in recent years, 1-stage exchange has gained more popularity with success rates of >90% for eradication of infection (Giulieri et al. Citation2004, Winkler et al. Citation2008, De Man et al. Citation2011, Singer et al. Citation2012, Zeller et al. Citation2014, Ilchmann et al. Citation2016).

In patients with aseptic loosening, uncemented revision stems have shown excellent medium- and long-term survival (Regis et al. Citation2011, Fink et al. Citation2014). In patients with PJI, 2-stage revision with an uncemented implant is also an established option, with excellent event-free survival rates (Koo et al. Citation2001, Masri et al. Citation2007, Fink et al. Citation2009, Kim et al. Citation2011, Romano et al. Citation2011, Neumann et al. Citation2012, Dieckmann et al. Citation2014). However, uncemented stems are still rarely used in 1-stage exchange (Zeller et al. Citation2014, Ilchmann et al. Citation2016), and there are no data on detailed radiological outcome. In septic revisions, the stability of uncemented stems may be impaired due to reduced ingrowth caused by low bone quality (Ochsner Citation2011) and also, in 1-stage exchange, by peri-implant osteomyelitis.

We assessed (1) the clinical outcome, including reoperation due to persistent infection and any other reoperation, and (2) the detailed radiological outcome after 1- and 2-stage revision, using an uncemented stem.

Patients and methods

Study population

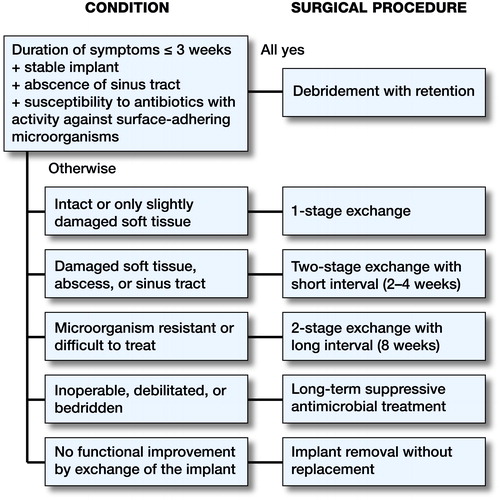

PJI after THA was diagnosed if at least 1 of the following criteria were fulfilled: (1) growth of the same microorganism in 2 or more cultures of synovial fluid, sonication fluid, or periprosthetic tissue; (2) purulence of synovial fluid or at the implant site; (3) acute inflammation on histopathological examination of periprosthetic tissue, and (4) presence of a sinus tract communicating with the prosthesis (Zimmerli et al. Citation2004). Patients were treated in an interdisciplinary unit for orthopedic infections and selected for a 1- or 2-stage exchange according to a well-established algorithm () (Zimmerli et al. Citation2004, Trampuz and Zimmerli Citation2005).

Figure 1. Surgical treatment algorithm for prosthetic joint infections. Modified according to Trampuz and Zimmerli (Citation2005).

Between January 1993 and December 2012, 251 hips were revised, 150 (60%) of them for PJI. In 81 (54%) of the infected hips (79 patients, 49 males, average age 70 (31–88) years), an uncemented revision stem was used (1-stage: 28; 2-stage: 53). 25 of the 1-stage procedures (Ilchmann et al. Citation2016) and 26 of the 2-stage procedures (De Man et al. Citation2011) have been included in previous publications. The decision to use uncemented stem fixation depended on the age of the patient and on bone quality. 29 patients had had at least 1 previous partial or total revision. In the 1-stage exchanges, the median length of time between onset of symptoms and revision was 35 (5–133) weeks, and in the 2-stage exchanges the median time was 26 (1–416) weeks. Follow-up after reimplantation was at 6, 12, and 26 weeks and at 1, 2, and 5 years—and every 5 years thereafter.

Surgical procedure and antimicrobial therapy

Procedures were performed or supervised by 3 surgeons (TI, PEO, and MC). They were done either via an extended trochanteric osteotomy (ETO, 58 hips, (Bircher et al. Citation2001)), a Hardinge approach (9 hips), or a transtrochanteric access (TT, 14 hips), depending on the type of the infected implant (cemented or uncemented), its stability (fixed or loose), bone quality, and the surgeon’s preferences.

In 1-stage exchanges, old scars were excised. Afterwards, all foreign material was removed (implants, broken screws, bone cement, sutures, bone grafts). In addition, a thorough synovectomy was performed without removal of vital bone and soft tissue in order not to compromise function of the joint. Afterwards, the wound was rinsed with 3–5 L of polyhexanide (Lavasept) and antibiotic therapy was started according to the microbiological results (Zimmerli and Clauss Citation2015). Drapes and instruments were not changed after removal of the infected implant in 1-stage procedures.

In 2-stage exchanges, a hand-made spacer was inserted in 30 hips, using standard gentamicin cement (Palacos R + G; Heraeus, Weinheim Germany). A temporary Girdlestone procedure with soft-tissue extension was performed in 16 hips. In 7 hips, the spacer was secondarily removed and converted to a Girdlestone situation, due to difficult-to-treat bacteria according to the definitive microbiological results. Difficult-to-treat microorganisms included those that were resistant to antibiotics with good oral bioavailability, rifampin-resistant staphylococci, small-colony variants, enterococci, quinolone-resistant Gram-negative bacilli, and fungi (Trampuz and Zimmerli Citation2005). All patients with difficult-to-treat microorganisms were managed with 2-stage exchange with a long interval (> 8 weeks) and a 6-week antibiotic treatment by the intravenous route.

For reimplantation, the same approach was used as for hardware removal. Either a monoblock (Wagner SL, n = 59; 1-stage: 17; 2-stage: 42) or a modular (Revitan, n = 22; 1-stage: 11; 2-stage: 11) distal anchoring titanium fluted revision stem was used (both from Zimmer, Winterthur, Switzerland). Care was taken to achieve a distal anchoring length of at least 5 cm. Reaming was not conducted further than 1 cm past the planned tip of the stem. The reamer was checked for bone mill adherence, to ensure anchoring into vital bone (Ochsner Citation2003). 45 acetabular-reinforcement rings (ARR; Muller) and 33 anti-protrusion cages (Burch-Schneider) were used in combination with a cemented low-profile polyethylene (PE) cup (all from Zimmer, Winterthur, Switzerland), using standard gentamicin cement for cup fixation (Palacos R + G). Implantation was performed according to an established technique (van Koeveringe and Ochsner Citation2002, Ochsner Citation2003). In 3 hips, an Allofit press-fit cup was implanted (Zimmer, Winterthur, Switzerland). Postoperative mobilization was standardized with 15 kg partial weight bearing for 6 weeks, followed by stepwise increase up to full weight bearing within the 6 weeks that followed. In the case of an ETO, flexion was restricted to 70° for the first 6 weeks.

All patients underwent an antimicrobial treatment according to a previously described protocol (Zimmerli et al. Citation2004). Briefly, during the first 2 weeks, they were treated by the intravenous route, followed by oral therapy for 3 months. In patients with 2-stage exchange with a short interval, antibiotics were not stopped before reimplantation, and treatment was continued for 3 months. Patients with 1-stage exchange or 2-stage exchange with a short interval were treated with biofilm-active antibiotics, namely rifampin against staphylococci and a fluoroquinolone against Gram-negative bacilli (Zimmerli et al. Citation2004, Sendi and Zimmerli Citation2012). In staphylococcal PJI, oral rifampin was added to the intravenous treatment regimen as soon as the wound was dry, in order to avoid superinfection with a rifampin-resistant microorganism (Achermann et al. Citation2013). After 2 weeks, rifampin was continued and the intravenous treatment was switched to an oral drug combination according to the susceptibility testing, usually including a fluoroquinolone. In Gram-negative PJI, the initial intravenous therapy was switched to an oral fluoroquinolone as soon as the wound was dry. In patients with 2-stage exchange and a long interval between, antibiotics were stopped after 6 weeks, i.e. at least 2 weeks before reimplantation. Patients undergoing 2-stage exchange with a long interval were not treated with a biofilm-active antibiotic if no material was left in place.

Radiological analysis

At each follow-up, a set of radiographs, according to our in-house standard, was obtained, including an anterior-posterior (AP) pelvic view centered on the symphysis, a false-profile view, and an AP view of the femur showing the whole prosthesis. For analysis, all images were corrected for magnification using the true size of the femoral head.

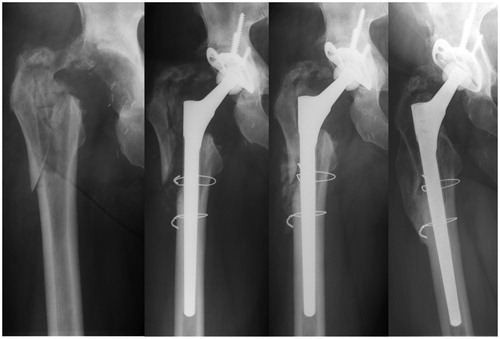

Acetabular defects were classified according to Paprosky et al. (Citation1994) and femoral defects were classified according to Pak et al. (Citation1993). Subsidence was measured as described by Callaghan et al. (Citation1985). 5 mm or more was considered relevant (Fink et al. Citation2014). Restoration of the proximal femur after ETO was classified according to Bohm and Bischel (Citation2004) and scored as: (A) increasing defects, (B) constant defects, (C) visible bone restoration, (D) good bone restoration (complete restoration of the bone tube below the intertrochanteric region), or (E) excellent bone restoration (complete restoration of the bone tube including the intertrochanteric region)) ().

Figure 2. 57-year-old male patient (2-stage exchange, ETO, Wagner SL, ARR). Girdlestone hip (a) due to difficult-to-treat bacteria (small-colony variant of S. aureus), postoperatively (b), and after 3 months (c). Complete remodeling of the proximal femur at 5 years (d).

Progressive radiolucent lines of >2 mm at the bone-stem interface were described with respect to their location, using 10 modified Gruen zones in both planes. For ETO, the zones were distributed distal to the osteotomy around the stem. For endofemoral or TT revisions, the zones were placed along the distal stem contact area. A stem was considered radiologically loose when there were progressive circumferential radiolucent lines or when there was progressive subsidence (> 5 mm) in a painful joint. On the acetabular side, progressive radiolucencies of >2 mm were classified into 3 zones, as described by DeLee and Charnley.

Implant survival

The mean clinical follow-up time was 7 (2–15) years. The mean radiological follow-up time was 5 (2–15) years (1-stage: 5 (2–12) years; 2-stage: 5 (2–15) years). 17 patients died after 9 (3–15) years for reasons unrelated to the infection or surgery. No patients were lost to follow-up or were excluded.

Event-free implant survival was calculated using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis for various endpoints: (1) persistence of infection, (2) aseptic loosening of the stem, and (3) revision of any component for any reason. Persistence of infection was assumed when at least 1 of the following criteria were fulfilled: persistent local clinical signs of infection, lack of normalization of C-reactive protein without any other explanation, new sinus tract formation, early loosening of the implant (< 2 years), or detection of the same microorganism during a subsequent diagnostic or therapeutic procedure.

Statistics

For comparison of defect sizes and femoral remodeling in 2 groups, the Mann-Whitney U-test was used. For comparison of subsidence and radiolucent lines in 2 different groups, either Fisher’s exact test or the chi-square test was used. Event-free survival was calculated using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis. This might overestimate the risk of revision compared to estimates using competing-risk methods (Gillam et al. Citation2010), but the Kaplan-Meier estimates are clinically more meaningful and more straightforward to interpret for clinicians (Ranstam et al. Citation2011).

For comparison of event-free survival rates, a log-rank test was used. SPSS Statistics 23 was used. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Microbiology and antibiotic therapy for PJI

One-third of the episodes were caused by coagulase-negative staphylococci (CNS) and one-third by Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) (). No episodes were caused by a methicillin-resistant S. aureus strain and no rifampin-resistant staphylococci were encountered. 3 cases were caused by small-colony variants that we considered difficult-to-treat, and these were treated with a 2-stage exchange with soft-tissue extension (Zimmerli et al. Citation2004). There was no change in the range of bacteria that we considered to be difficult-to-treat during the follow-up period. None of the patients were treated with suppressive antibiotics after the planned course.

Table 1. Etiology of the 81 episodes of PJI. The total number of microorganisms was higher than the number of episodes, because 14 episodes were polymicrobial

Re-revisions after treatment of PJI

There was no relapse of infection and there were no new episodes of infection in the group with 1-stage exchange. In the group with 2-stage exchange, there were 3 cases of persistent infection. The infections were diagnosed 6 months, 1 year, and 4 years after reimplantation, and the microorganisms were CNS (n = 1) or S. aureus (n = 2). 2 of these persistent infections were successfully treated with a second 2-stage exchange. In the third patient, PJI with S. aureus could not be controlled and emergency hip exarticulation was performed because of life-threatening sepsis.

3 stems were revised for reasons not related to infection. 2 in the 1-stage group were revised for aseptic loosening, 1 after 0.7 years with excessive subsidence (26 mm; Wagner SL) and 1 after 5 years (Revitan). 1 hip in the 2-stage group was revised due to a fractured stem 7 years after implantation (Wagner SL).

In 1 case with an extended cranial acetabular defect (2-stage exchange), the cup was revised twice for aseptic loosening—after 3 and 6 years. Intraoperative samples from both revisions did not reveal any bacterial growth. 1 cup (in the same case as the fractured stem; see above) was revised 2 months after PJI revision for recurrent dislocation.

There was only 1 re-revision after 7 years (stem fracture after 7.2 years), and the results in the patients with longer follow-up (up to 15 years) did not deteriorate.

Outcome analysis

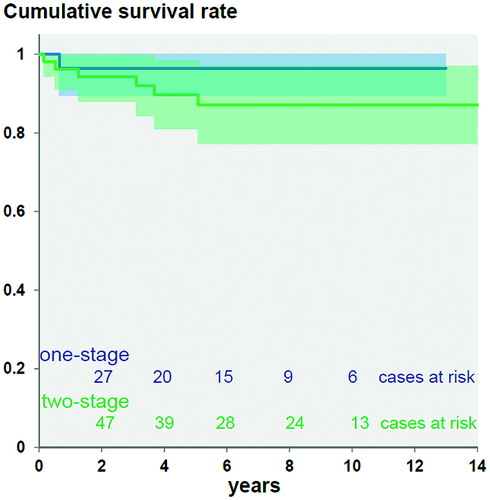

The 7-year infection-free survival was 96% (95% CI: 92–100), 100% for 1-stage revision and 94% for 2-stage revision (95% CI: 87–100) (). Cure from infection was not statistically significantly different after 1-stage and 2-stage procedures (p = 0.2).

Figure 3. Kaplan-Meier survival with revision for infection as endpoint after 7 years was 100% for 1-stage exchange and 94% (95% CI: 87–100) for 2-stage exchange. There was no statistically significant difference between the groups (p = 0.2).

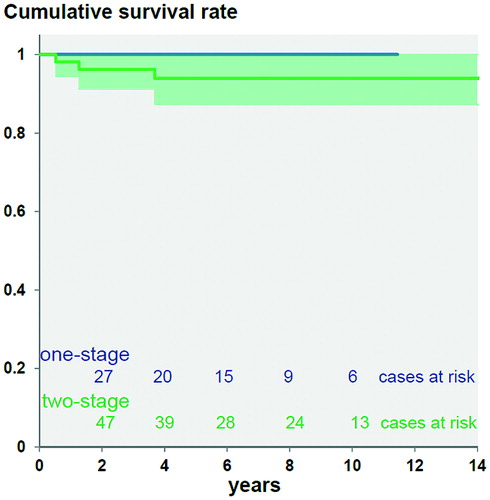

The 7-year survival for aseptic loosening of the stem was 97% (95% CI: 93–100), 97% for 1-stage revision (95% CI: 90–100) and 97% for 2-stage revision (95% CI: 92–100) (). There was no statistically significant difference between 1-stage and 2-stage procedures (p = 0.3), and no significant difference between stem types (p = 0.5).

Figure 4. Kaplan-Meier survival with revision for aseptic stem loosening as endpoint after 7 years was 96% (95% CI: 90–100) for 1-stage exchange and 97% (95% CI: 92–100) for 2-stage exchange. There was no statistically significant difference between the groups (p = 0.8).

The 7-year revision-free survival for any cause was 90% (95% CI: 83–97), 96% for 1-stage revision (95% CI: 90–100) and 87% for 2-stage revision (95% CI: 77–96) (p = 0.3) ().

Radiological results

Preoperative defects – before index surgery, acetabular and femoral defects were more severe in the 2-stage group than in the 1-stage group (p < 0.001) ().

Table 2. Distribution of acetabular and femoral defects

Subsidence (≥ 5 mm) was detected in 6 stems. It always occurred within the first 3 months after implantation. No statistically significant difference was found between stem types (4 Wagner SL and 2 Revitan; p = 0.7) and types of revision (3 were 1-stage revisions and 3 were 2-stage revisions; p = 0.41). 1 subsided stem (Wagner SL, 1-stage) was re-revised for aseptic loosening. In the other 5 stems, no revision was performed—the reasons being patient refusal, the poor general condition of the patient, having only subtle symptoms, or lack of symptoms.

Femoral remodeling – in 3 patients, remodeling was not listed due to missing radiographs after index surgery. After ETO (n = 58), proximal femoral remodeling was excellent (n = 32) or good (n = 9) in two-thirds of the episodes. Only visible bone restoration was observed in 9 hips. Constant (n = 4) or even increasing bone defects (n = 1) were found in one-tenth of the stems. No statistically significant differences were found between stem types (p = 0.3) and between 1- and 2-stage exchange (p = 0.2).

Radiolucent lines around the stem were observed in 8 implants (5 Wagner and 3 Revitan; 2 one-stage and 6 two-stage). On the acetabular side, a radiolucent line was observed in 2 implants. In one cup (2-stage procedure; Allofit press-fit cup), the stem (Revitan) had a radiolucent line too; both components were revised for aseptic loosening 5 years after implantation without evidence of persistent or new PJI. The second case (ARR, 2-stage, Wagner SL) showed persistence of infection and underwent another 2-stage exchange. Of the implants that were not re-revised, none were rated as being radiologically loose according to the above-mentioned criteria.

Discussion

PJI is one of the most devastating complications after THA. Surgical treatment strategies include implant retention, 1-stage exchange, 2-stage exchange, and resection arthroplasty. The optimal management strategy is the least invasive one that will result in complete elimination of the microorganism(s) and preservation of good joint function (Zimmerli et al. Citation2004). According to the results presented here, cure of infection, implant survival, and radiological outcome were similar for both 1-stage and 2-stage exchange in patients treated according to our algorithm. Thus, an uncemented stem could be implanted without compromising the elimination of microorganisms and the fixation of the implant.

We started to use our algorithm in 1993. After publication, it became a well-established treatment protocol (Zimmerli et al. Citation2004, Osmon et al. Citation2013). In the present study we found an overall success rate for infection-free survival of 96% (95% CI: 92–100), which is rather high compared to the literature, where 70%-100% has been reported (). The high success rate with 1-stage exchange is because of the algorithm, which excludes patients with risk factors for failure (). In addition, in all patients undergoing 1-stage exchange, a biofilm-active antimicrobial agent has been used (rifampin against staphylococci and a fluoroquinolone against Gram-negative bacilli). Each patient with suspected PJI was discussed by the multidisciplinary team before surgery and on regular rounds in the specialized unit.

Table 3. Summary of the literature concerning 1- and 2-stage cementless revisions in PJI

Concerning aseptic loosening of the stem, we found an excellent 7-year survival of 97% (95% CI: 93–100), which is comparable to the figures of 92% and 99% reported for uncemented revision stems used in cases of aseptic loosening (Bohm and Bischel Citation2004, Regis et al. Citation2011, Fink et al. Citation2014, Baktir et al. Citation2015).

The long-term success of cementless revision stems requires good primary stability without subsidence, due to sufficient press-fit fixation and a stable ingrowth of the implant (i.e. secondary stability). For the Revitan and Wagner SL stems, the rate of subsidence of more than 5 mm has been reported to be around 3% in aseptic revisions (Regis et al. Citation2011, Fink et al. Citation2014). In our series, we found a frequency of approximately 7%—which always occurred within the first 3 months after implantation. The slightly higher rate might be due to a more distal and less even bone preparation due to removal of distally well-fixed implants and cement, or delayed osteointegration in an osteomyelitic femur. This highlights the importance of meticulous preparation of the bone bed in the distal femur, as previously described (Ochsner Citation2003).

Proximal femoral remodeling after osteotomy (ETO and TT) was good or excellent in two-thirds of the hips. Similar remodeling is reported in patients with aseptic revisions (Fink et al. Citation2011, Drexler et al. Citation2014, Megas et al. Citation2014, Baktir et al. Citation2015). Thus, bone healing is not compromised, despite the invasiveness of the approach and the presence of infection. This is an important finding, since we see the controlled osteotomy of the femur as a step that is crucial for the success of treatment. It facilitates proper debridement of the femoral canal and complete removal of distal cement and plug. Furthermore, it makes distal reaming manageable, ensuring distal anchoring of the stem into a vital bone stock—and it does not compromise function (Ochsner Citation2003, De Man et al. Citation2011).

In summary, surgical management of PJI with stratification to 1- or 2-stage procedures in accordance with our algorithm (Zimmerli et al. Citation2004), combined with appropriate antimicrobial therapy (Sendi and Zimmerli Citation2012), allows the safe use of uncemented revision stems even in the case of 1-stage procedures. Implant survival seems to be comparable to that in revisions for aseptic loosening.

PB: data analysis and writing of manuscript. TI: interpretation of data and critical revision of manuscript. WZ: treatment concepts, interpretation of data, and critical revision of manuscript. LZ: interpretation of data, statistical analysis, and database management. PG: critical revision of manuscript. PO: treatment concepts, interpretation of data, and critical revision of manuscript. MC: data analysis, interpretation of data, and writing and revision of manuscript.

No competing interests declared. No external funding was received.

- Achermann Y, Eigenmann K, Ledergerber B, Derksen L, Rafeiner P, Clauss M, Nuesch R, Zellweger C, Vogt M, Zimmerli W. Factors associated with rifampin resistance in staphylococcal periprosthetic joint infections (PJI): a matched case-control study. Infection 2013; 41(2): 431–7.

- Baktir A, Karaaslan F, Gencer K, Karaoglu S. Femoral revision using the Wagner SL revision stem: a single-surgeon experience featuring 11-19 years of follow-up. J Arthroplasty 2015; 30 (5): 827–34.

- Bircher H P, Riede U, Luem M, Ochsner P E. [The value of the Wagner SL revision prosthesis for bridging large femoral defects]. Orthopade 2001; 30 (5): 294–303.

- Boettner F, Cross M B, Nam D, Kluthe T, Schulte M, Goetze C. Functional and emotional results differ after aseptic vs septic revision hip arthroplasty. HSS J 2011; 7 (3): 235–8.

- Bohm P, Bischel O. The use of tapered stems for femoral revision surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2004; (420): 148–59.

- Callaghan J J, Salvati E A, Pellicci P M, Wilson P D, Jr., Ranawat C S. Results of revision for mechanical failure after cemented total hip replacement, 1979 to 1982. A two to five-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1985; 67 (7): 1074–85.

- Dale H, Fenstad A M, Hallan G, Havelin L I, Furnes O, Overgaard S, Pedersen A B, Karrholm J, Garellick G, Pulkkinen P, Eskelinen A, Makela K, Engesaeter L B. Increasing risk of prosthetic joint infection after total hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2012; 83 (5): 449–58.

- De Man F H, Sendi P, Zimmerli W, Maurer T B, Ochsner P E, Ilchmann T. Infectiological, functional, and radiographic outcome after revision for prosthetic hip infection according to a strict algorithm. Acta Orthop 2011; 82 (1): 27–34.

- Dieckmann R, Schulz D, Gosheger G, Becker K, Daniilidis K, Streitburger A, Hardes J, Hoell S. Two-stage hip revision arthroplasty with a hexagonal modular cementless stem in cases of periprosthetic infection. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2014; 15: 398.

- Drexler M, Dwyer T, Chakravertty R, Backstein D, Gross A E, Safir O. The outcome of modified extended trochanteric osteotomy in revision THA for Vancouver B2/B3 periprosthetic fractures of the femur. J Arthroplasty 2014; 29 (8): 1598–604.

- Fink B, Grossmann A, Fuerst M, Schafer P, Frommelt L. Two-stage cementless revision of infected hip endoprostheses. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009; 467 (7): 1848–58.

- Fink B, Grossmann A, Schulz M S. Bone regeneration in the proximal femur following implantation of modular revision stems with distal fixation. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2011; 131 (4): 465–70.

- Fink B, Urbansky K, Schuster P. Mid term results with the curved modular tapered, fluted titanium Revitan stem in revision hip replacement. Bone Joint J 2014; 96-B (7): 889–95.

- Gillam M H, Ryan P, Graves S E, Miller L N, de Steiger R N, Salter A. Competing risks survival analysis applied to data from the Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry. Acta Orthop 2010; 81 (5): 548–55.

- Giulieri S G, Graber P, Ochsner P E, Zimmerli W. Management of infection associated with total hip arthroplasty according to a treatment algorithm. Infection 2004; 32 (4): 222–8.

- Ilchmann T, Zimmerli W, Ochsner P E, Kessler B, Zwicky L, Graber P, Clauss M. One-stage revision of infected hip arthroplasty: outcome of 39 consecutive hips. Int Orthop 2016; 40(5): 913–8.

- Kim Y H, Kim J S, Park J W, Joo J H. Cementless revision for infected total hip replacements. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011; 93 (1): 19–26.

- Koo K H, Yang J W, Cho S H, Song H R, Park H B, Ha Y C, Chang J D, Kim S Y, Kim Y H. Impregnation of vancomycin, gentamicin, and cefotaxime in a cement spacer for two-stage cementless reconstruction in infected total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2001; 16 (7): 882–92.

- Kurtz S M, Lau E, Watson H, Schmier J K, Parvizi J. Economic burden of periprosthetic joint infection in the United States. J Arthroplasty 2012; 27 (8 Suppl): 61–5 e1.

- Masri B A, Panagiotopoulos K P, Greidanus N V, Garbuz D S, Duncan C P. Cementless two-stage exchange arthroplasty for infection after total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2007; 22 (1): 72–8.

- Megas P, Georgiou C S, Panagopoulos A, Kouzelis A. Removal of well-fixed components in femoral revision arthroplasty with controlled segmentation of the proximal femur. J Orthop Surg Res 2014; 9: 137.

- Neumann D R, Hofstaedter T, List C, Dorn U. Two-stage cementless revision of late total hip arthroplasty infection using a premanufactured spacer. J Arthroplasty 2012; 27 (7): 1397–401.

- Ochsner P E. Total Hip Replacement. In: Total Hip Replacement. (Ed. Ochsner PE). Springer-Verlag: Berlin; 2003; 15–57.

- Ochsner P E. Osteointegration of orthopaedic devices. Semin Immunopathol 2011; 33 (3): 245–56.

- Osmon D R, Berbari E F, Berendt A R, Lew D, Zimmerli W, Steckelberg J M, Rao N, Hanssen A, Wilson W R. Diagnosis and management of prosthetic joint infection: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America 2013; 56 (1): e1–e25.

- Pak J H, Paprosky W G, Jablonsky W S, Lawrence J M. Femoral strut allografts in cementless revision total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1993; (295): 172–8.

- Paprosky W G, Perona P G, Lawrence J M. Acetabular defect classification and surgical reconstruction in revision arthroplasty. A 6-year follow-up evaluation. J Arthroplasty 1994; 9 (1): 33–44.

- Ranstam J, Karrholm J, Pulkkinen P, Makela K, Espehaug B, Pedersen A B, Mehnert F, Furnes O. Statistical analysis of arthroplasty data. II. Guidelines. Acta Orthop 2011; 82 (3): 258–67.

- Regis D, Sandri A, Bonetti I, Braggion M, Bartolozzi P. Femoral revision with the Wagner tapered stem: a ten- to 15-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011; 93 (10): 1320–6.

- Romano C L, Romano D, Meani E, Logoluso N, Drago L. Two-stage revision surgery with preformed spacers and cementless implants for septic hip arthritis: a prospective, non-randomized cohort study. BMC Infect Dis 2011; 11: 129.

- Sendi P, Rohrbach M, Graber P, Frei R, Ochsner P E, Zimmerli W. Staphylococcus aureus small colony variants in prosthetic joint infection. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 43 (8): 961–7.

- Sendi P, Zimmerli W. Antimicrobial treatment concepts for orthopaedic device-related infection. Clin Microbiol Infect 2012; 18 (12): 1176–84.

- Singer J, Merz A, Frommelt L, Fink B. High rate of infection control with one-stage revision of septic knee prostheses excluding MRSA and MRSE. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2012; 470 (5): 1461–71.

- Trampuz A, Zimmerli W. Prosthetic joint infections: update in diagnosis and treatment. Swiss Med Wkly 2005; 135 (17-18): 243–51.

- van Koeveringe A J, Ochsner P E. Revision cup arthroplasty using Burch-Schneider anti-protrusio cage. Int Orthop 2002; 26 (5): 291–5.

- Winkler H, Stoiber A, Kaudela K, Winter F, Menschik F. One stage uncemented revision of infected total hip replacement using cancellous allograft bone impregnated with antibiotics. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2008; 90 (12): 1580–4.

- Zeller V, Lhotellier L, Marmor S, Leclerc P, Krain A, Graff W, Ducroquet F, Biau D, Leonard P, Desplaces N, Mamoudy P. One-stage exchange arthroplasty for chronic periprosthetic hip infection: results of a large prospective cohort study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2014; 96 (1): e1.

- Zimmerli W, Clauss M. Periprosthetic joint infections after total hip and knee arthroplasty. In: Bone and joint infections from microbiology to diagnostics and treatment. (Ed. Zimmerli W). Wiley Blackwell: Chichester; 2015; 1; 131–50.

- Zimmerli W, Trampuz A, Ochsner P E. Prosthetic-joint infections. N Engl J Med 2004; 351 (16): 1645–54.