Abstract

Background and purpose — The number of patients who are suitable for outpatient total hip and knee arthroplasty (THA and TKA) in an unselected patient population remains unknown. The purpose of this prospective 2-center study was to identify the number of patients suitable for outpatient THA and TKA in an unselected patient population, to investigate the proportion of patients who were discharged on the day of surgery (DOS), and to identify reasons for not being discharged on the DOS.

Patients and methods — All consecutive, unselected patients who were referred to 2 participating centers and who were scheduled for primary THA and TKA were screened for eligibility for outpatient surgery with discharge to home on DOS. If patients did not fulfill the discharge criteria, the reasons preventing discharge were noted. Odds factors with relative risk intervals for not being discharged on DOS were identified while adjusting for age, sex, ASA score, BMI and distance to home.

Results — Of the 557 patients who were referred to the participating surgeons during the study period, 54% were potentially eligible for outpatient surgery. Actual DOS discharge occurred in 13–15% of the 557 patients. Female sex and surgery late in the day increased the odds of not being discharged on the DOS.

Interpretation — This study shows that even in unselected THA and TKA patients, same-day discharge is feasible in about 15% of patients. Future studies should evaluate safety aspects and economic benefits.

Fast-track total hip and knee arthroplasty (THA and TKA) has been shown to reduce perioperative morbidity and mortality and result in shorter convalescence (Malviya et al. Citation2011, Husted Citation2012, Kehlet Citation2013) . Such optimized patient treatment through well-described evidence-based clinical pathways with multimodal opioid-sparing anesthesia, early mobilization with full weight bearing, and modern surgical techniques has led to a worldwide decrease in length of stay (LOS) after THA and TKA in the last decades. Outpatient arthroplasty can be seen as the ultimate goal of fast-track surgery, and it has gained popularity in recent years (Argenson et al. Citation2016, Parvizi Citation2017). In this context, increased focus on reducing healthcare costs has further fueled interest in outpatient surgery (Healy et al. Citation2002, Bertin Citation2005, Aynardi et al. Citation2014, Lovald et al. Citation2014b). Studies in selected patients have shown that outpatient arthroplasty is possible, both for THA (Berger Citation2007, Dorr et al. Citation2010, Hartog et al. Citation2015) and for TKA (Berger et al. Citation2005, Lovald et al. Citation2014a). While it is widely accepted that outpatient arthroplasty should only be performed on selected patients (Rozell et al. Citation2017) and with several selection criteria for outpatient cases (Kort et al. Citation2016), the optimal patient selection remains debatable. Furthermore, the number of patients suitable for outpatient THA and TKA in an unselected patient population remains unknown, limiting the external validity of previous studies.

The purpose of this prospective study was (1) to identify the proportion of patients suitable for outpatient THA and TKA in an unselected patient population, (2) to investigate the proportion of patients who can be discharged on the day of surgery (DOS), and (3) to identify reasons preventing patients from being discharged on the DOS.

Patients and methods

All consecutive and unselected patients referred to 2 surgeons at Vejle Hospital and to all but 1 surgeon (n = 7) at Hvidovre University Hospital and scheduled for primary THA or TKA were screened for participation in the study between December 2015 and June 2016. In general, as part of the Danish socialized healthcare system (with no “private” patients), all patients for THA and TKA at both participating centers are randomly referred to a surgeon without selection. However, to avoid selection bias, we identified 22 selected patients (who were referred specifically to a particular surgeon by name) and excluded them. All referred patients were screened for possible outpatient surgery using well-defined criteria, during the initial outpatient visit. Patients with sleep apnea requiring treatment were excluded due to safety concerns, if those patients were to be sent home with opioids (Van Ryswyk and Antic Citation2016). Unselected patients with an ASA score of <3, who could be operated as number 1 or 2 in the operating room, were considered eligible for possible outpatient surgery. Surgeons assigned patients to be number 1, 2, or 3 in the operating room at random, based on personal preference and logistics in the operating room. Patients operated as number 3 in the operating room were excluded, as those patients were not likely to be back in the patient ward in time to be seen by a physiotherapist, to fulfill the functional discharge criteria and to be then sent home on the DOS. Patients who were deemed eligible for outpatient surgery were informed of possible discharge on the DOS, and that the treatment and the discharge criteria were the same for all patients. An adult had to be present at home for at least 24 h following discharge in order for the patients to participate in outpatient surgery, and patients who did not fulfill this criterion were excluded before surgery.

The treatment of all patients was standardized at both departments, and was the same for all patients—both those who underwent outpatient surgery and those who did not. All operations were performed in a standardized fast-track setup (Husted Citation2012) by experienced surgeons specialized in THA and TKA surgery. The standard surgical protocol for both THA and TKA included spinal anesthesia, standardized fluid management, use of preoperative intravenous tranexamic acid (TXA), preoperative single-shot, high-dose methylprednisolone (Lunn et al. Citation2011, Citation2013), and absence of drains. All THAs were performed using a standard posterolateral approach. All TKAs were performed with a standard medial parapatellar approach without the use of a tourniquet and using local infiltration analgesia (LIA) (Andersen and Kehlet Citation2014). The patients were transferred from the postoperative recovery unit to the patient ward after a few hours, where immediate mobilization was attempted, allowing full weight bearing. Physiotherapy was started on the day of surgery and continued until discharge. Rivaroxaban (Bayer, Denmark) was used as oral thromboprophylaxis, starting 6–8 h postoperatively and continuing daily until discharge. Mechanical thromboprophylaxis and extended oral thromboprophylaxis were not used.

After the patients were back in the ward, the nurse and the physiotherapist continuously screened them for fulfillment of discharge criteria on the DOS. Discharge criteria for DOS discharge consisted of functional discharge criteria that applied to all patients, together with some additional criteria (). Patients who fulfilled the DOS discharge criteria were discharged to home. If a patient did not fulfill the discharge criteria, the reasons preventing discharge were noted. If several discharge criteria were not met, all of them were noted. Distance to home was registered for all patients as <10 km, 10–50 km, and >50 km. Patients discharged on the DOS received a courtesy phone call at 10 p.m., and were asked to contact the department in case of any problems.

Table 1. Criteria for discharge on the day of surgery (DOS)

Statistics

Data were compared using the Pearson chi-squared test. Multiple logistical regression analysis was used to identify odds factors for not being discharged on the DOS (while adjusting for age, sex, ASA score, BMI, and distance to home). An odds ratio (OR) for increased odds of not being discharged on the DOS was calculated for all factors from the regression analysis. To illustrate the difference between the OR and the relative risk (RR), a range for RR has been calculated for each factor, based on all possible strata/subgroups for a given factor (Grant Citation2014). Correlations were considered significant when p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed in R 3.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical computing, Vienna, Austria).

Ethics, funding, and potential conflicts of interest

No approval from the National Ethics Committee was necessary, as this was a non-interventional observational study. The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (entry no. 20047-58-0015).

This work was sponsored by grants from the Lundbeck Foundation and ZimmerBiomet. The Lundbeck Foundation and ZimmerBiomet had no influence on any part of the study or on the content of the paper.

Results

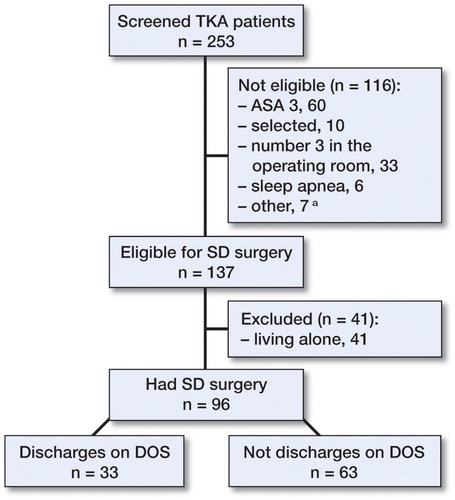

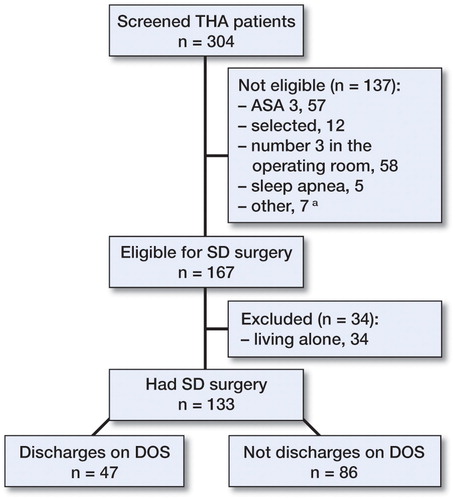

557 patients were referred to the participating surgeons during the study period and were screened for eligibility for outpatient surgery (209 patients from Vejle Hospital and 348 patients from Hvidovre Hospital). 304 patients (54%) fulfilled the criteria for undergoing outpatient surgery, 167 THA patients and 137 TKA patients ( and ). The proportion of patients who were not eligible for outpatient surgery differed slightly between the 2 departments, with respect to ASA score and selected patients (Table 2, see Supplementary data). Of the 302 patients who were eligible for outpatient surgery, 28% of the THA patients (n = 47) and 24% of the TKA patients (n = 33) were discharged on the DOS ( and ). This accounts for 15% (95% CI:12–20) and 13% (95% CI: 9–18) of all referred and screened THA and TKA patients, respectively. Apart from lack of motivation and not fulfilling the discharge criteria, lack of safe mobilization was the most common reason for THA and TKA patients not being discharged (Table 3, see Supplementary data). Female sex and being number 2 in the operating room statistically significantly increased the odds of not being discharged on the DOS, with the RR of not being discharged being 0.4–0.7 for male patients and 1.0–1.7 for patients operated as number 2 in the operating room (). A male patient, < 75 years old, with BMI <35, ASA ≤2, undergoing THA surgery as the first in the operating room and living >50 km from the hospital had a 68% chance of being discharged on the DOS (). A female patient, > 75 years old with BMI >35 had only a 9% chance of being discharged on the DOS ().

Figure 1. Flow chart for inclusion of TKA patients for same-day (SD) discharge. a Language problems (1), low compliance (4), living at a nursing home (1), and unknown (1).

Figure 2. Flow chart for inclusion of THA patients for same-day (SD) discharge. a Chronic pain (1), cancer (1), low compliance (3), and unknown (2).

Table 4. Logistic regression analysis. Odd ratios for not being discharged on day of surgery. The lower limit and upper limit for RR estimates are also presented

Table 5. Probability of being discharged on the day of surgery (DOS) for a reference patientTable Footnotea and change in probability of being discharged on DOS for a single changed parameter from the reference patient

Table 6. Probability of being discharged on the day of surgery (DOS) for different combinations of significant (gender) and near-significant (age and BMI) patient-related factors

Discussion

In this prospective 2-center study, we found that 28% of THA patients and 24% of TKA patients who were eligible for outpatient surgery were discharged on DOS, which accounted for 15% (95% CI: 12–20) and 13% (95% CI: 9–18) of all unselected patients who were referred to THA and TKA and screened in this study. In both THA patients and TKA patients, we also found that besides lack of motivation and not fulfilling discharge criteria, inability to mobilize safely was the most common reason for not being discharged.

To our knowledge, no previous studies have investigated eligibility and feasibility of outpatient surgery in an unselected healthcare population. Patient selection for outpatient surgery is the subject of debate, and many different criteria have been suggested (Kort et al. Citation2016) based on age, comorbidities, and BMI (Berger et al. Citation2005, Citation2009, Kolisek et al. Citation2009, Dorr et al. Citation2010, Aynardi et al. Citation2014, Hartog et al. Citation2015, Goyal et al. Citation2017) Some proposed patient selection criteria for outpatient surgery are quite extensive, and the question remains how many patients would be eligible from an unselected population. To our knowledge, only 1 study has described the background population from which the candidates for outpatient surgery were selected: Goyal et al. (Citation2017) assessed 70% of all referred patients and found that only 14% did not fulfill the inclusion criteria for outpatient arthroplasty. This contrasts with our findings, as we only found 54% of patients to be eligible candidates for outpatient surgery, despite having much broader inclusion criteria. A more selective patient referral at other centers may be a possible explanation, as all the patients who were assessed for eligibility in our study were unselected, and in a non-private, socialized healthcare system. The proportion of patients who were found to be eligible for outpatient THA and TKA differed between the 2 hospitals, as did the proportion of patients excluded due to having an ASA score of >3. This was most likely due to different patient demographics in the referral population, as the 2 hospitals are located in different parts of the country. Since both hospitals receive the majority of unselected referrals from the local region (with very few selected patients from other regions), our findings demonstrate that outpatient TKA and THA is feasible in an unselected patient population.

Around 25% of the patients who were eligible for outpatient surgery in our study were discharged on the DOS. This contrasts with the much higher discharge rates for DOS reported by Goyal et al. (Citation2017) (75%), Hartog et al. (Citation2015) (89%), Parcells et al. (Citation2016) (98%), Chen and Berger (Citation2013) (99%), Berger et al. (Citation2009) (93%), and Rolighed Larsen et al. (Citation2017) (85%). There are several possible explanations. Firstly, our patient selection was much broader than in other studies, as we did not exclude patients based on BMI, age, or distance to home. This gave us more patients who were eligible for outpatient surgery, but at the same time reduced the overall rate of discharge on DOS. However, the broader inclusion allows better determination of the patient characteristics that influence readiness for discharge on DOS. Secondly, all our patients were discharged to their own homes without the possibility of intervention by home-based nurses for the first night, which may have influenced the degree of motivation in the patients. Thirdly, our discharge criteria may differ from other studies, i.e. maximum blood loss limit of 500 mL may exclude some patients, who otherwise could have been included if this limit was removed or set higher. Fourthly, even though discharge could take place until 8 p.m., the physiotherapist was only available until 6 p.m., thus reducing the time to achieve fulfillment of the discharge criteria. Finally, all our patients received the same care and were admitted to the same ward, so patients eligible for outpatient surgery with the possibility of discharge on DOS were mixed with patients who were not eligible for same-day discharge. This may have reduced the motivation for early discharge, compared to patients operated in dedicated outpatient facilities (Parcells et al. Citation2016).

When comparing studies on outpatient surgery, it is important to consider definitions for outpatient surgery and discharge location for patients. In our view, “true” outpatient surgery involves discharge of the patients to their own home, as discharge to a care facility simply moves the admission and associated resources to a different location (cost shifting). Also, while most studies have defined outpatient surgery as discharge on DOS, some studies have defined it as a length of stay of <23 hours (Kolisek et al. Citation2009). From a financial point of view, only patients who are discharged on DOS should be considered to be true outpatients, as these patients could be treated in a dedicated outpatient care facility without the need for an overnight stay. Overall, our finding that 54% of unselected patients were eligible candidates for outpatient surgery, with 13–15% of all unselected screened patients actually being discharged on DOS, shows that while outpatient surgery is definitely feasible in an unselected healthcare population, it is not for everyone, and strict selection criteria should be applied.

We found that in both THA patients and TKA patients, inability to mobilize safely was the most common reason for not being discharged, while there was blood loss of >500 mL in 27% of THA patients—which is in accordance with previous studies showing postoperative nausea and vomiting and muscle weakness in 12% of THA patients and 23% of TKA patients on the first postoperative day (Husted et al. Citation2011). This gives surgeons targets for intervention to optimize early safe mobilization, with focus on orthostatic intolerance (Jans and Kehlet 2016) and blood saving strategies.

We found that male patients had a substantially higher chance of being discharged on DOS, which is in accordance with previous findings showing that male patients have a shorter LOS than female patients (Hayes et al. Citation2000, Mathijssen et al. Citation2016, Sibia et al. Citation2016). Also, we found that older patients (> 75 years old) and patients with BMI >35 showed a trend of having a lower chance of being discharged on DOS, which is also supported by some previous findings showing that higher BMI and higher age have a negative effect on LOS (Maradit Kremers et al. Citation2014, Mathijssen et al. Citation2016, Petis et al. Citation2016, Sibia et al. Citation2016) This, however, contrasts with a recent study which found that only THA patients with high BMI had an increased risk of prolonged LOS, and that this did not apply to TKA patients (Husted et al. Citation2016). An important finding in the present study was that about 25% of patients who were eligible candidates for outpatient surgery could not participate, as they were living alone and could not have an adult with them for >24 hours after same-day discharge ( and ). Thus, social support and social network should be part of the selection criteria for outpatient surgery.

The main limitation of the present study is that we only considered the process of selection of patients and possible same-day discharge without investigating the safety aspects of outpatient surgery. However, this was not the purpose of the study, as our goal was firstly to investigate the feasibility of outpatient arthroplasty in an unselected healthcare population. The safety aspects of outpatient surgery are of crucial importance and are a matter of debate, as some studies have shown that outpatient arthroplasty surgery is safe (Berger et al. Citation2009, Kolisek et al. Citation2009, Hartog et al. Citation2015) while others have found an increased risk of complications and re-admissions in outpatient patients (Lovecchio et al. Citation2016). A large follow-up study focusing on aspects of safety, such as complications, re-admissions, outcomes, and patient satisfaction is warranted. Also, a higher discharge percentage can be achieved by more selective patient inclusion and by using dedicated outpatient pathways. However, the broad patient selection for this study can be considered to be a strength, as it allows investigations with higher external validity regarding future health economic analyses. Our discharge criteria can be debated, and may have differed from those at other institutions. For instance, the 500-mL blood loss limit was not based on evidence but was set only as a safety consideration. Similarly, the requirement for relatives to be present for 24 hours for patients discharged on the day of surgery was also a safety consideration, and might be required for a shorter period of time or be abandoned altogether. Finally, the surgeons assigned patients the number 1, 2, or 3 in the operating room randomly, based on personal preference and logistics. While this allows for some selection” bias”, as patients eligible for same-day discharge (based on other criteria) could be selected as number 1 or 2 in the operating room, this does not affect the conclusions from the study, as we have described the characteristics of all the participating patients and screened patients.

In summary, we found that 54% of unselected patients were eligible candidates for outpatient surgery and that 13–15% of all screened patients were discharged on the day of surgery. Possible targets for outpatient pathway optimization were social network support, safe mobilization and improved blood saving strategies. Thus, further studies investigating safety considerations and the potential financial benefits of outpatient surgery are warranted.

Supplementary data

Tables 2 and 3 are available in the online version of this article.

KG, KH, PK, and HH planned the study. KG, PK, and PR collected the data. KG and HH analyzed the data. KG wrote the manuscript. It was revised and accepted by all the authors.

IORT_A_1314158_Supp.pdf

Download PDF (25.8 KB)- Andersen L Ø, Kehlet H. Analgesic efficacy of local infiltration analgesia in hip and knee arthroplasty: a systematic review. Br J Anaesth 2014; 113(3): 360–74.

- Argenson J-N A, Husted H, Lombardi A, Booth R E, Thienpont E. Global forum: An international perspective on outpatient surgical procedures for adult hip and knee reconstruction. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2016; 98(13): e55.

- Aynardi M, Post Z, Ong A, Orozco F, Sukin D C. Outpatient surgery as a means of cost reduction in total hip arthroplasty: a case-control study. HSS J 2014; 10(3): 252–5.

- Berger R A. A comprehensive approach to outpatient total hip arthroplasty. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2007; 36(9 Suppl): 4–5.

- Berger R A, Sanders S, Gerlinger T, Della Valle C, Jacobs J J, Rosenberg A G. Outpatient total knee arthroplasty with a minimally invasive technique. J Arthroplasty 2005; 20 (7 Suppl 3): 33–8.

- Berger R A, Sanders S A, Thill E S, Sporer S M, Della Valle C. Newer anesthesia and rehabilitation protocols enable outpatient hip replacement in selected patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009; 467(6): 1424–30.

- Bertin K C. Minimally invasive outpatient total hip arthroplasty: a financial analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2005; (435): 154–63.

- Chen D, Berger R A. Outpatient minimally invasive total hip arthroplasty via a modified Watson-Jones approach: technique and results. Instr Course Lect 2013; 62: 229–36.

- Dorr L D, Thomas D J, Zhu J, Dastane M, Chao L, Long W T. Outpatient total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2010; 25(4): 501–6.

- Goyal N, Chen A F, Padgett S E, Tan T L, Kheir M M, Hopper R H, et al. Otto Aufranc Award: A multicenter, randomized study of outpatient versus inpatient total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2017; 475(2): 364–72.

- Grant R L. Converting an odds ratio to a range of plausible relative risks for better communication of research findings. BMJ 2014; 348: f7450.

- Hartog Y M den, Mathijssen N M C, Vehmeijer S B W. Total hip arthroplasty in an outpatient setting in 27 selected patients. Acta Orthop 2015; 86(6): 667–70.

- Hayes J H, Cleary R, Gillespie W J, Pinder I M, Sher J L. Are clinical and patient assessed outcomes affected by reducing length of hospital stay for total hip arthroplasty? J Arthroplasty 2000; 15(4): 448–52.

- Healy W L, Iorio R, Ko J, Appleby D, Lemos D W. Impact of cost reduction programs on short-term patient outcome and hospital cost of total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2002; 84-A(3): 348–53.

- Husted H. Fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty: clinical and organizational aspects. Acta Orthop 2012; 83 (Suppl 346): 1–39.

- Husted H, Lunn T H, Troelsen A, Gaarn-Larsen L, Kristensen B B, Kehlet H. Why still in hospital after fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty? Acta Orthop 2011; 82(6): 679–84.

- Husted H, Jørgensen CC, Gromov K, Kehlet H. Does BMI influence hospital stay and morbidity after fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty? Acta Orthop 2016; 87(5): 466–72.

- Jans Ø, Kehlet H. Postoperative orthostatic intolerance: a common perioperative problem with few available solutions. Can J Anaesth 2017; 64(1): 10–15.

- Kehlet H. Fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty. Lancet 2013; 381(9878): 1600–2.

- Kolisek F R, McGrath M S, Jessup N M, Monesmith E A, Mont M A. Comparison of outpatient versus inpatient total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009; 467(6): 1438–42.

- Kort N P, Bemelmans Y F L, van der Kuy P H M, Jansen J, Schotanus M G M. Patient selection criteria for outpatient joint arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2016 Apr 22; [Epub ahead of print]

- Lovald S, Ong K, Lau E, Joshi G, Kurtz S, Malkani A. Patient selection in outpatient and short-stay total knee arthroplasty. J Surg Orthop Adv 2014a; 23(1): 2–8.

- Lovald S T, Ong K L, Malkani A L, Lau E C, Schmier J K, Kurtz S M, et al. Complications, mortality, and costs for outpatient and short-stay total knee arthroplasty patients in comparison to standard-stay patients. J Arthroplasty 2014b; 29(3): 510–5.

- Lovecchio F, Alvi H, Sahota S, Beal M, Manning D. Is outpatient arthroplasty as safe as fast-track inpatient arthroplasty? A propensity score matched analysis. J Arthroplasty 2016; 31(9 Suppl): 197–201.

- Lunn T H, Kristensen B B, Andersen L Ø, Husted H, Otte K S, Gaarn-Larsen L, et al. Effect of high-dose preoperative methylprednisolone on pain and recovery after total knee arthroplasty: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Br J Anaesth 2011; 106(2): 230–8.

- Lunn T H, Andersen L O, Kristensen B B, Husted H, Gaarn-Larsen L, Bandholm T, et al. Effect of high-dose preoperative methylprednisolone on recovery after total hip arthroplasty: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Br J Anaesth 2013; 110(1): 66–73.

- Malviya A, Martin K, Harper I, Muller S D, Emmerson K P, Partington P F, et al. Enhanced recovery program for hip and knee replacement reduces death rate. Acta Orthop 2011; 82(5): 577–81.

- Maradit Kremers H, Visscher S L, Kremers W K, Naessens J M, Lewallen D G. Obesity increases length of stay and direct medical costs in total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2014; 472(4): 1232–9.

- Mathijssen N M C, Verburg H, van Leeuwen C CG, Molenaar T L, Hannink G. Factors influencing length of hospital stay after primary total knee arthroplasty in a fast-track setting. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2016; 24(8): 2692–6.

- Parcells B W, Giacobbe D, Macknet D, Smith A, Schottenfeld M, Harwood D A, et al. Total joint arthroplasty in a stand-alone ambulatory surgical center: short-term outcomes. Orthopedics 2016; 39(4): 223–8.

- Parvizi J. CORR Insights(®): Otto Aufranc Award: A multicenter, randomized study of outpatient versus inpatient total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2017; 475(2): 373–4.

- Petis S M, Howard J L, Lanting B A, Somerville L E, Vasarhelyi E M. Perioperative predictors of length of stay after total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2016; 31(7): 1427–30.

- Rolighed Larsen J, Skovgaard B, Prynø T, Bendikas L, Mikkelsen L R, Laursen M, et al. Feasibility of day-case total hip arthroplasty: a single-centre observational study. Hip Int 2017; 27(1): 60–5.

- Rozell J C, Courtney P M, Dattilo J R, Wu C H, Lee G C. Late complications following elective primary total hip and knee arthroplasty: who, when, and how? J Arthroplasty 2017; 32(3): 719–23.

- Van Ryswyk E, Antic N. Opioids and sleep disordered breathing. Chest 2016; 150(4): 934–44.

- Sibia U S, MacDonald J H, King P J. Predictors of hospital length of stay in an enhanced recovery after surgery program for primary total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2016; 31(10): 2119–23.