Abstract

Background and purpose — Fast-tracking shortens the length of the primary treatment period (length of stay, LOS) after total knee replacement (TKR). We evaluated the influence of the fast-track concept on the length of uninterrupted institutional care (LUIC) and other outcomes after TKR.

Patients and methods — 4,256 TKRs performed in 4 hospitals between 2009–2010 and 2012–2013 were identified from the Finnish Hospital Discharge Register and the Finnish Arthroplasty Register. Hospitals were classified as fast track (Hospital A) and non-fast track (Hospitals B, C and D). We analyzed length of uninterrupted institutional care (LUIC), LOS, discharge destination, readmission, revision, manipulation under anesthesia (MUA) and mortality rate in each hospital. We compared these outcomes for TKRs performed in Hospital A before and after fast-track implementation and we also compared Hospital A outcomes with the corresponding outcomes for the other 3 hospitals.

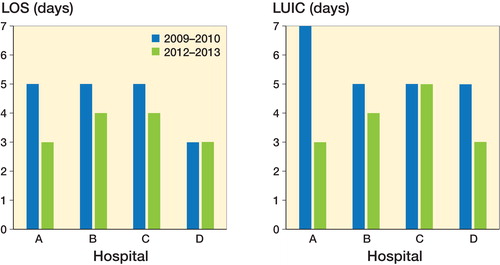

Results — After fast-track implementation, median LOS in Hospital A fell from 5 to 3 days (p < 0.001) and (median) LUIC from 7 to 3 (p < 0.001) days. These reductions in LOS and LUIC were accompanied by an increase in the discharge rate to home (p = 0.01). Fast-tracking in Hospital A led to no increase in 14- and 42-day readmissions, MUA, revision or mortality compared with the rates before fast-tracking, or with those in the other hospitals. Of the 4 hospitals, LOS and LUIC were most reduced in Hospital A.

Interpretation — A fast-track protocol reduces LUIC and LOS after TKR without increasing readmission, complication or revision rates.

The aim of fast-tracking is to optimize the whole treatment protocol, leading eventually to shorter length of stay (LOS) without compromising treatment quality (Husted Citation2012). For selected patients, even same-day discharge after TKR is feasible (Gromov et al. Citation2017, Hoorntje et al. Citation2017). Fast-track TKR is not associated with higher readmission, reoperation, manipulations under anesthesia (MUA) or mortality rates (Husted et al. Citation2010b, 2014, Glassou et al. Citation2014, Wied et al. Citation2015, Winther et al. Citation2015, Jørgensen et al. Citation2017).

In Finnish hospitals, LOS and length of uninterrupted institutional care (LUIC) after TKR have universally decreased over the past decade (Pamilo et al. Citation2015). In previous fast-track studies, the overall reduction in LOS, even without fast-tracking, has rarely been taken into account (Glassou et al. Citation2014). Apart from studies on LOS conducted only on hospitals directly discharging to home, 100% of patients (Husted et al. Citation2010b, Citation2011a, Jørgensen et al. Citation2013a), no reports have been published on total length of uninterrupted institutional care (LUIC) after fast-track TKR. It is important to enhance the efficiency of these procedures, i.e., lower their economic impact, without compromising their outcomes (Andreasen et al. Citation2016).

By combining Finnish Arthroplasty Register and hospital discharge register data and benchmarking data from 4 different hospitals, we evaluated the effect of introducing fast-tracking on LUIC, LOS, discharge destination, readmissions, early revision, MUA and mortality rates after TKR.

Patients and methods

For this study, we selected 4 similar Finnish public central hospitals, all with some teaching responsibilities, from a benchmarking database maintained by Nordic Healthcare Group Ltd (NHG). Implementation of a fast-track protocol started in September 2011 in Hospital A, which soon after that date fulfilled all the fast-track criteria. The other hospitals (Hospitals B, C, and D) did not meet the fast-track criteria to the same extent. For fast-track criteria and characteristics of the hospitals, see Pamilo et al. (Citation2017).

A hospital was classified as a fast-track hospital if it fulfilled all the fast-track criteria as evaluated from answers to a written questionnaire sent to each hospital in the study.

Patient education and information in Hospital A was planned to give the patient all the information needed to enable early discharge. Preoperative education included patient education seminars and an outpatient session with an orthopedic surgeon and a nurse. Written standardized information was given to all patients and included a phone number to be called in case of any questions.

This study is based on the PERFECT hip and knee replacement databases (Mäkelä et al. Citation2011), which collect data from the Finnish Hospital Discharge Register (FHDR) and the Finnish Arthroplasty Register (FAR), cause-of-death statistics (Statistics Finland) and drug prescription and drug reimbursement registers (Social Insurance Institution). All public and private hospitals in Finland are obliged to report all surgical procedures to the FHDR. In comparison with the FHDR, the FAR coverage for primary knee replacements in the 4 target hospitals during the study period was 91% in Hospital A, 96% in Hospital B, 81% in Hospital C and 97% in Hospital D (Institute for Health and Welfare Citation2017). We evaluated LOS, LUIC, discharge destination, presence at home 1 week post-surgery, readmissions, revisions, MUAs and mortality during 2 2-year periods, 1 before (2009–2010) and 1 after (2012–2013) fast-track implementation in Hospital A. Patients were followed up until the end of 2015. The results for Hospital A were also compared with those for the other hospitals (Hospitals B, C and D). However, the readmission and MUA rates were not compared with those of the other hospitals due to variation in the readmission and MUA criteria.

For definition and calculation of LOS and LUIC, see Pamilo et al. (Citation2017).

Inclusion criteria

The study population was formed by selecting patients from the FHDR according to the WHO International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10 Citation2010) and applying the following criteria: M17.0/M17.1 for primary osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee. The codes for primary TKR were NGB20, NGB30, NGB40 and NGB50, according to the NOMESCO classification of surgical procedures, Finnish version. The accuracy of the diagnosis of primary OA was double-checked against the relevant data in the FAR. It should be noted that the length of the surgical treatment period, the length of institutional care, and unscheduled readmissions were evaluated for total knee replacements—not patients.

Exclusion criteria

TKRs performed for secondary OA and revisions were excluded (Appendix 1). A diagnosis of secondary knee OA was noted retrospectively from the beginning of 1987. A patient was excluded from the study if a diagnosis of secondary knee OA had been recorded in the Hospital Discharge Register between the beginning of 1987 and the day of the operation. Patients listed in the Social Insurance Institution database as eligible for reimbursement for the sequelae of transplantation, uremia requiring dialysis, rheumatoid arthritis, or connective tissue disease were excluded from the study. We also excluded patients who were not Finnish citizens or were residents of the autonomous region of Åland.

Readmission

Readmission was recorded if the patient had been readmitted after discharge to any ward in any hospital in Finland during the first 14 or 42 days from the index operation. Direct transfer to another hospital was not counted as a readmission. Only the first readmissions for any reason after the index operation (also readmissions not directly related to the index TKR operation) were included in the study.

Revision and MUA

A search for revision surgery on the same knee after TKR was conducted using codes NGC00–NGC99 and for MUA using code NGT60. A search for removal of the total prosthesis from the knee was made in the FAR. Patients were followed up until the end of 2015. Only first revisions within 1 year and first MUA of the same knee within 6 months of the primary TKR were included. Non-standardized indications for MUA were flexion <90 degrees or unsatisfactory flexion.

Discharge destination

Some patients are admitted to hospital from other social and welfare institutions and therefore are unlikely to be discharged home. Thus, only patients who came from home to hospital for their TKR were included in the discharge destination analyses. The percentage of patients who were at home 1 week after TKR was also analyzed irrespective of the hospital discharge destination.

Statistics

The same statistical procedures were used as in Pamilo et al. (Citation2017).

Ethics, funding, and potential conflicts of interest

Permission for the study was obtained from each register and from each study hospital. No ethics permission was required to perform this registry study. No grants were received to conduct this study. No conflicts of interest are declared.

Results

4,256 TKRs meeting the inclusion but not exclusion criteria were identified from the FHDR and FAR. Of these, 437 were performed in Hospital A before, and 624 after, implementation of the fast-track protocol. The corresponding numbers in the other hospitals were 367 and 442 in Hospital B, 501 and 514 in Hospital C, and 641 and 730 in Hospital D. No statistically significant age or sex differences were observed before or after fast-tracking in Hospital A, or between hospital A and the other hospitals.

Primary hospital stay

Before implementing fast-tracking, the median LOS in Hospital A was 5 (CI 3–9) days: thereafter, it fell to 3 (CI 1–5) days (p < 0.001) (). After fast-tracking, LOS was statistically significantly shorter in Hospital A than in Hospitals B (4 days; CI 3–14) (p < 0.001) or C (4 days; CI 3–6) (p < 0.05). Unlike the other study hospitals, after fast-tracking, Hospital A discharged 5% of the TKR patients home on the first postoperative day. Despite the post-fast-tracking reduction in LOS, Hospital A’s discharge destination rates to home increased (from 66% to 75%) (p = 0.01). However, Hospitals B and C, with longer LOS, continued to discharge more TKR patients directly home than Hospital A (p < 0.001). Hospital D showed similar LOS (3 days; CI 3–5) and discharge rate (71%) to home as Hospital A after fast-tracking.

Episode

Median LUIC in Hospital A was 7 (CI 3–24) days before fast-tracking and 3 (CI 2–20) days (p < 0.001) thereafter (). After fast-track implementation, median LUIC was shorter in Hospital A than hospital C (5 days; CI 4–22) (p < 0.01) but not significantly shorter than in Hospitals B (4 days; CI 3–14) or D (3 days; CI 3–14). The percentage of patients at home a week after TKR increased from 48% before fast-tracking to 75% thereafter in Hospital A (p < 0.001). After fast-tracking in Hospital A, this percentage was higher only in Hospital B (84%, p < 0.001).

Quality and complications

In Hospital A, the rate of revision TKR (within 1 year after the primary operation) was 1.1% (CI 0.0–2.2) between 2009 and 2010 and 2.4% (CI 1.4–3.4) in patients operated between 2012 and 2013 (NS). No statistically significant differences in revision rates were observed before or after the implementation of fast-tracking in Hospital A between the 4 hospitals (). The rate of MUA (during the first 6 months after the primary operation) was 6.4% (CI 5.1–7.8) before and 5.9% (CI 4.8–7.0) after fast-tracking in Hospital A.

Table 1. Adjusted revision rates and mortality during 1 year in 2-year periods for primary total knee arthroplasty in four different hospitalsTable Footnotea

Unscheduled readmissions and mortality

In Hospital A, the 14-day readmission rate was 2.4% (CI 1.1–3.6) before and 1.6% (CI 0.5–2.8) after fast-tracking, and the corresponding 42-day readmission rates were 6.0% (CI 3.9–8.2) and 6.1% (CI 4.3–7.9). The reasons for readmission recorded in the hospital discharge register are given in Table 2 (see Supplementary data).

Mortality at 1 year after TKR in Hospital A was 0.8% (CI 0.7–0.9) before and 0.7% (CI 0.6–0.7) after fast-tracking (). Mortality rates were similar between the hospitals.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of a fast-track protocol on LOS and LUIC after TKR. Median LOS and LUIC both decreased along with an increase in the discharge rate directly to home and without any significant change in readmission, revision surgery or MUA. We have recently reported similar findings for THA (Pamilo et al. Citation2017)

Validity of the data

The level of completeness and accuracy in the FHDR is satisfactory (Sund Citation2012) and the coverage of FAR is good (Institute for Health and Welfare Citation2017). The strength of our study is the inclusion of data from all the private and public hospitals in Finland. Thus, all revisions, MUAs and readmissions were included in the analyses. Only 1 hospital (A) in our study had fully implemented the fast-track protocol. In addition to fast-tracking, the changes in the studied parameters may also in part be explained by other factors, such as other processual changes and differences in the annual arthroplasty volume of surgeons.

LOS

Several factors have been reported to affect LOS: surgeon volume, hospital volume, time between surgery and mobilization, process standardization (such as fast-track programs), operation day and patient-related factors (Judge et al. Citation2006, Mitsuyasu et al. Citation2006, Bozic et al. Citation2010, Husted et al. Citation2010a, Paterson et al. Citation2010, Styron et al. Citation2011, Pamilo et al. Citation2015, Jans et al. Citation2016, Mathijssen et al. Citation2016). An annual decline in LOS after TKR, even in the absence of a fast-track protocol, has been reported (Cram et al. Citation2012, Pamilo et al. Citation2015). The same observation was also made in the hospitals studied here. The effect of this annual decline in LOS has not usually been taken into account in earlier fast-track studies (Husted et al. Citation2010b, den Hartog et al. Citation2013, Winther et al. Citation2015). Thus, it can be argued either that the effect of fast-tracking on LOS has been overestimated in those studies or that non-fast-track hospitals have adopted some of the features of fast-tracking, resulting in shorter LOS. The latter possibility was also discussed by Glassou et al. (Citation2014) in their study.

In line with our previous report on fast-track THR (Pamilo et al. Citation2017), we found in this study that fast-track implementation in Hospital A resulted in a statistically significant decrease in LOS and LUIC. Our finding of a median LOS of 3 days accords with previous reports on LOS after fast-track TKR (Husted et al. Citation2010b, Citation2016, Glassou et al. Citation2014, Winther et al. Citation2015, Pitter et al. Citation2016). After fast-tracking, median LUIC in our study was 3 days, which mimics the results of studies of hospitals discharging all their patients directly home (Husted et al. Citation2010b, Citation2011a, Jørgensen et al. Citation2013a). The other hospitals in our study had implemented some elements of the fast-track protocol (Pamilo et al. (Citation2017). However, median LOS and LUIC decreased statistically significantly only in Hospital A, which had systematically and comprehensively implemented fast-tracking to its full extent. Further, while LOS was shorter in Hospital A after fast-track implementation than in Hospitals B or C, LUIC was statistically significantly shorter only when compared with Hospital C.

Discharge destination

Patient expectation, one of the most important factors predicting discharge destination (Halawi et al. Citation2015), presents a challenge for preoperative patient education. Discharging TKR patients to a skilled care facility has been associated with higher readmission rates (Keswani et al. Citation2016, McLawhorn et al. Citation2017). The economic wisdom of discharging patients to an extended institutional care facility instead of allowing longer LOS has also been disputed (Sibia et al. Citation2017). 1 earlier fast-track study reported a discharge rate to home after TKR of 80%, both before and after fast-tracking (Winther et al. Citation2015). In our study, the discharge destination rate to home increased statistically significantly (66% to 75%) after fast-tracking, as also did the proportion of patients at home 1 week after surgery. The last-mentioned accords with our previous report after THR (Pamilo et al. Citation2017). Hospitals B and C, in which LOS was longer, nevertheless discharged more TKR patients directly home than either Hospitals A or D. Hospitals B and C, unlike A and D, were aiming at short stay throughout the study period via patient education.

Unscheduled readmissions

Unscheduled readmissions are widely used as a marker of quality of care. However, comparison of readmission rates between studies is difficult, because definitions of readmission, and diagnoses, vary between studies. Moreover, readmissions to other hospitals have not been included in all the previous studies (Ramkumar et al. Citation2015). A recent systematic review found the readmission rate after TKR to be 3.3% within 30 days and 9.7% within 90 days, with surgical site infection as the leading reason (Ramkumar et al. Citation2015). Although we included all events that required care in any hospital and in any ward, our finding of a 42-day readmission rate (6%) with no increase after fast-tracking is in line with previous fast-track reports (Jørgensen et al. Citation2013b, Husted et al. Citation2016).

Revision and MUA

The revision rate after fast-track TKR has been reported to be between 1.4% and 2% within 90 days and 3.3% within one year (Husted et al. Citation2008, Citation2011b, Glassou et al. Citation2014, Winther et al. Citation2015). In line with Glassou et al. (Citation2014), no significant difference was observed in revision rates before and after fast-tracking in Hospital A or between Hospital A’s pre- and post-fast-tracking revision rates and those of the other 3 hospitals.

In our earlier study, we found no association between short LOS and increased risk for MUA (Pamilo et al. Citation2015). Moreover, in line with our present results, no increase in the incidence of MUA rates after fast-tracking has been reported (Husted et al. Citation2015, Wied et al. Citation2015).

Mortality

Death after TKR is relatively rare event and not always surgery-related (Jørgensen et al. Citation2017). An enhanced recovery program has been found to be associated with a significant or nearly significant reduction in mortality after TKR and THR (Malviya et al. Citation2011, Savaridas et al. Citation2013, Khan et al. Citation2014). However, for patients with a comorbidity burden at the time of surgery mortality risk has not declined (Glassou et al. Citation2017). In our study, the 1-year mortality rate was 0.7% after fast-tracking. This is a little lower than the 1-year mortality 1.3% reported by Savaridas et al. (Citation2013), but their study also included THR patients. Other studies have reported 90-day mortality rates of 0.2%–0.5% after fast-track THR and TKR (Husted et al. Citation2010b, Malviya et al. Citation2011, Khan et al. Citation2014, Glassou et al. Citation2017, Jørgensen et al. Citation2017).

Summary

Process standardization by fast-tracking protocols offers an opportunity to substantially reduce LUIC and LOS. In addition, implementation of fast-tracking increases the discharge rate to home. Fast-track protocols do not appear to increase complication or revision rates.

Supplementary data

Table 2 and Appendices 1 and 2 are available as supplementary data in the online version of this article, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17453674.2017.1399643

KJP, PT, MiP, MaP, VR, and JP wrote the manuscript. PT and MiP performed the data analysis. All contributed to the conception and design of the study, to critical analyses of the data, to interpretation of the findings, and to critical revision of the manuscript.

Acta thanks Per Kjaersgaard-Andersen for help with peer review of this study.

IORT_A_1399643_SUPP.PDF

Download PDF (27.6 KB)- Andreasen S E, Holm H B, Jørgensen M, Gromov K, Kjaersgaard-Andersen P, Husted H. Time-driven activity-based cost of fast-track total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2016; 32: 1747–55.

- Bozic K J, Maselli J, Pekow P S, Lindenauer P K, Vail T P, Auerbach A D. The influence of procedure volumes and standardization of care on quality and efficiency in total joint replacement surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010; 92 (16): 2643–52.

- Cram P, Lu X, Kates S L, Singh J A, Li Y, Wolf B R. Total knee arthroplasty volume, utilization, and outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries, 1991–2010. JAMA 2012; 308 (12): 1227–36.

- den Hartog Y M, Mathijssen N M, Vehmeijer S B. Reduced length of hospital stay after the introduction of a rapid recovery protocol for primary THA procedures. Acta Orthop 2013; 84 (5): 444–7.

- Glassou E N, Pedersen A B, Hansen T B. Risk of re-admission, reoperation, and mortality within 90 days of total hip and knee arthroplasty in fast-track departments in Denmark from 2005 to 2011. Acta Orthop 2014; 85 (5): 493–500.

- Glassou E N, Pedersen A B, Hansen T B. Is decreasing mortality in total hip and knee arthroplasty patients dependent on patients’ comorbidity? Acta Orthop 2017; 88 (3): 288–93.

- Gromov K, Kjaersgaard-Andersen P, Revald P, Kehlet H, Husted H. Feasibility of outpatient total hip and knee arthroplasty in unselected patients. Acta Orthop 2017; 88 (5): 516–21.

- Halawi M J, Vovos T J, Green C L, Wellman S S, Attarian D E, Bolognesi M P. Patient expectation is the most important predictor of discharge destination after primary total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2015; 30 (4): 539–42.

- Hoorntje A, Koenraadt K L M, Boevé M G, van Geenen R C I. Outpatient unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: Who is afraid of outpatient surgery? Knee Surgery, Sport Traumatol Arthrosc 2017; 25 (3): 759–66.

- Husted H. Fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty: Clinical and organizational aspects. Acta Orthop 2012; 83 (Suppl 346): 1–39.

- Husted H, Holm G, Jacobsen S. Predictors of length of stay and patient satisfaction after hip and knee replacement surgery: Fast-track experience in 712 patients. Acta Orthop 2008; 79 (2): 168–73.

- Husted H, Hansen H C, Holm G, Bach-Dal C, Rud K, Andersen K L, et al. What determines length of stay after total hip and knee arthroplasty? A nationwide study in Denmark. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2010a; 130 (2): 263–8.

- Husted H, Otte K S, Kristensen B B, Orsnes T, Kehlet H. Readmissions after fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2010b; 130 (9): 1185–91.

- Husted H, Lunn T H, Troelsen A, Gaarn-Larsen L, Kristensen B B, Kehlet H. Why still in hospital after fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty? Acta Orthop 2011a; 82 (6): 679–84.

- Husted H, Troelsen A, Otte K S, Kristensen B B, Holm G, Kehlet H. Fast-track surgery for bilateral total knee replacement. J Bone Jt Surg Br 2011b; 93 (3): 351–6.

- Husted H, Jørgensen C C, Gromov K, Troelsen A. Low manipulation prevalence following fast-track total knee arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2015; 86 (1): 86–91.

- Husted H, Jørgensen C C, Gromov K, Kehlet H. Does BMI influence hospital stay and morbidity after fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty? Acta Orthop 2016; 87 (5): 466–72.

- ICD-10. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems 10th revision [Internet] 2010 [cited 2017 Sep 15]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2010/en

- Institute for Health and Welfare. Finnish Arthroplasty Register [Internet] 2017 [cited 2017 May 15]. Available from: https://www.thl.fi/far//#data/cphd

- Jans O, Bandholm T, Kurbegovic S, Solgaard S, Kjaersgaard-Andersen P, Johansson P I, et al. Postoperative anemia and early functional outcomes after fast-track hip arthroplasty: A prospective cohort study. Transfusion 2016; 56 (4): 917–25.

- Jørgensen C C, Kehlet H, Group LFC for FH and KRC. Fall-related admissions after fast-track total hip and knee arthroplasty: Cause of concern or consequence of success? Clin Interv Aging 2013a; 8: 1569–77.

- Jørgensen C C, Kehlet H, Group LFC for FH and KRC. Role of patient characteristics for fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty. Br J Anaesth 2013b; 110 (6): 972–80.

- Jørgensen C C, Kehlet H, Soeballe K, Hansen T B, Husted H, Laursen M B, et al. Time course and reasons for 90-day mortality in fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2017; 61 (4): 436–44.

- Judge A, Chard J, Learmonth I, Dieppe P. The effects of surgical volumes and training centre status on outcomes following total joint replacement: Analysis of the Hospital Episode Statistics for England. J Public Health (Oxf) 2006; 28 (2): 116–24.

- Keswani A, Tasi M C, Fields A, Lovy A J, Moucha C S, Bozic K J. Discharge destination after total joint arthroplasty: An analysis of postdischarge outcomes, placement risk factors, and recent trends. J Arthroplasty 2016; 31 (6): 1155–62.

- Khan S K, Malviya A, Muller S D, Carluke I, Partington P F, Emmerson K P, et al. Reduced short-term complications and mortality following enhanced recovery primary hip and knee arthroplasty: Results from 6,000 consecutive procedures. Acta Orthop 2014; 85 (1): 26–31.

- Mäkelä K T, Peltola M, Sund R, Malmivaara A, Häkkinen U, Remes V. Regional and hospital variance in performance of total hip and knee replacements: a national population-based study. Ann Med 2011; 43 (Suppl 1): S31–S8.

- Malviya A, Martin K, Harper I, Muller S D, Emmerson K P, Partington P F, et al. Enhanced recovery program for hip and knee replacement reduces death rate. Acta Orthop 2011; 82 (5): 577–81.

- Mathijssen N M, Verburg H, van Leeuwen C C, Molenaar T L, Hannink G. Factors influencing length of hospital stay after primary total knee arthroplasty in a fast-track setting. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2016; 24 (8): 2692–6.

- McLawhorn A S, Fu M C, Schairer W W, Sculco P K, MacLean C H, Padgett D E. Continued inpatient care after primary total knee arthroplasty increases 30-day post-discharge complications: A propensity score-adjusted analysis. J Arthroplasty 2017; 32 (9S): 113–18.

- Mitsuyasu S, Hagihara A, Horiguchi H, Nobutomo K. Relationship between total arthroplasty case volume and patient outcome in an acute care payment system in Japan. J Arthroplasty 2006; 21 (5): 656–63.

- Pamilo K J, Peltola M, Paloneva J, Mäkelä K, Häkkinen U, Remes V. Hospital volume affects outcome after total knee arthroplasty: A nationwide registry analysis of 80 hospitals and 59,696 replacements. Acta Orthop 2015; 86 (1): 41–7.

- Pamilo K J, Torkki P, Peltola M, Pesola M, Remes V, Paloneva J. Reduced length of uninterrupted institutional stay after implementing a fast-track protocol for primary total hip replacement. Acta Orthop 2017; Sep 7: 1–7. [Epub ahead of print]

- Paterson J M, Williams J I, Kreder H J, Mahomed N N, Gunraj N, Wang X, et al. Provider volumes and early outcomes of primary total joint replacement in Ontario. Can J Surgery/Journal Can Chir 2010; 53 (3): 175–83.

- Pitter F T, Jørgensen C C, Lindberg-Larsen M, Kehlet H. Postoperative morbidity and discharge destinations after fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty in patients older than 85 years. Anesth Analg 2016; 122 (6): 1807–15.

- Ramkumar P N, Chu C T, Harris J D, Athiviraham A, Harrington M A, White D L, et al. Causes and rates of unplanned readmissions after elective primary total joint arthroplasty: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Orthop 2015; 44 (9): 397–405.

- Savaridas T, Serrano-Pedraza I, Khan S K, Martin K, Malviya A, Reed M R. Reduced medium-term mortality following primary total hip and knee arthroplasty with an enhanced recovery program. A study of 4,500 consecutive procedures. Acta Orthop 2013; 84 (1): 40–3.

- Sibia U S, Turcotte J J, MacDonald J H, King P J. The cost of unnecessary hospital days for Medicare joint arthroplasty patients discharging to skilled nursing facilities. J Arthroplasty 2017; 32 (9): 2655–7.

- Styron J F, Koroukian S M, Klika A K, Barsoum W K. Patient vs provider characteristics impacting hospital lengths of stay after total knee or hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2011; 26 (8): 1412–18.

- Sund R. Quality of the Finnish Hospital Discharge Register: A systematic review. Scand J Public Health 2012; 40 (6): 505–15.

- Wied C, Thomsen M G, Kallemose T, Myhrmann L, Jensen L S, Husted H, et al. The risk of manipulation under anesthesia due to unsatisfactory knee flexion after fast-track total knee arthroplasty. Knee 2015; 22 (5): 419–23.

- Winther S B, Foss O A, Wik T S, Davis S P, Engdal M, Jessen V, et al. 1-year follow-up of 920 hip and knee arthroplasty patients after implementing fast-track. Acta Orthop 2015; 86 (1): 78–85.