Abstract

Background and purpose — The multidisciplinary Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis and treatment of subacromial pain syndrome (SAPS) was created in 2012 by the Dutch Orthopedic Association. In brief, it stated that SAPS should preferably be treated nonoperatively. We evaluated the effect of the implementation of the guideline on the number of shoulder surgeries for SAPS in the Netherlands (17 million inhabitants).

Patients and methods — An observational study was conducted with the use of aggregated data from the national database of the Dutch Health Authority from 2012 to 2016. Information was collected on patients referred to and seen at orthopedic departments. Data from the following Diagnoses Related Groupings were analyzed: 1450 (tendinitis supraspinatus) and 1460 (rotator cuff tear).

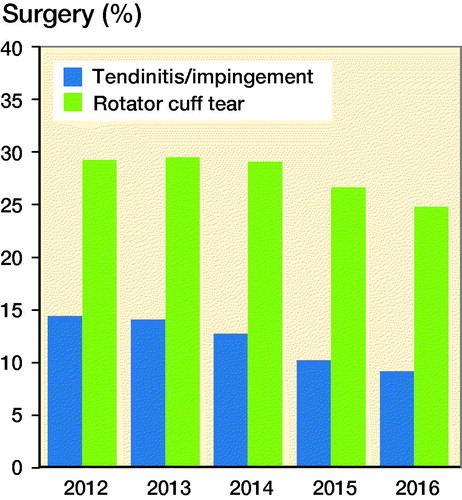

Results — In 2016 fewer patients were diagnosed with tendinitis supraspinatus than in 2012—a decrease from 49,491 to 44,662 (10%). Of the patients diagnosed with tendinitis, 14% were treated surgically in 2012; this number dropped to 9% by 2016. More patients with a rotator cuff tear were diagnosed in 2016 than in 2012, an increase from 17,793 to 23,389 (32%), fewer were treated surgically: 30% in 2012, compared with 25% in 2016.

Interpretation — After introducing the multidisciplinary Clinical Practice Guideline “Diagnosis and treatment of subacromial pain syndrome,” a decrease in shoulder surgeries for related diagnoses was observed in the Netherlands. The introduction and dissemination of this guideline seems to have contributed to the implementation of more appropriate health care and prevention of unnecessary surgeries.

Shoulder pain is a frequent complaint in the general population, with an incidence of 0.8–2.3% and a lifetime prevalence of up to 67% (Urwin et al. Citation1998, Luime et al. Citation2004). It is mainly seen in women over age 45 (Greving et al. Citation2012). The most frequent complaint is pain at the shoulder with overhead activities, and pain at night.

Neer (Citation1983)developed the concept of “impingement syndrome,” also called rotator cuff disease, bursitis, and supraspinatus tendinitis. None of these names cover the complex origin of subacromial pain with a painful arc, which nowadays is called “subacromial pain syndrome” (SAPS) (Papadonikolakis et al. Citation2011, Diercks et al. Citation2014b). Most of the symptoms usually resolve within a few months. Some patients show persistent symptoms despite physiotherapy and are referred to orthopedic surgeons to discuss open or arthroscopic bursectomy, acromioplasty, and/or rotator cuff repair.

In recent years increasing scientific evidence shows that patients’ results from surgical interventions are not better than treatment with physiotherapy and/or steroid injections (Dorrestijn et al. Citation2009, Björnsson Hallgren et al. Citation2017, Ketola et al. Citation2017). A randomized controlled trial (RCT) showed no benefit of acromioplasty compared with sham surgery or nonoperative treatment (Beard et al. Citation2018).

A clinical practice guideline for diagnosis and treatment of subacromial pain syndrome based on the available scientific evidence was created by the Dutch Orthopedic Society in 2012. The major recommendations were: SAPS should preferably be treated nonoperatively; patients who do not respond to exhaustive nonoperative treatment can be offered surgery; asymptomatic rotator cuff tears should not be treated surgically; when surgical repair of symptomatic rotator cuff tears is considered, the size of the tear, the condition of the muscles, and age and activity level of the patient are important factors to consider in the context of patient expectations; surgical treatment of tendinosis calcarea is not recommended.

To disseminate the guideline, presentations were given to the Dutch Orthopedic Society, the Rehabilitation Society and the Dutch Shoulder and Elbow Society. The guidelines were published in the Dutch Orthopedic Journal, the Dutch General Medical Journal (Diercks et al. Citation2014a), and Acta Orthopedica 2014 (Diercks et al. Citation2014b). Multiple presentations were held for national and regional symposia, physical therapists, and GPs.

We have now examined whether the referral and treatment patterns have changed following the presentation of the clinical practice guideline for SAPS.

Patients and methods

This observational study was conducted with use of aggregated data from the national database of the Dutch Health Authority from 2012 until 2016. All patients seen by a medical specialist in the Netherlands have specific codes registered for every diagnosis and treatment. The following diagnosis-related groupings (DRG) (in Dutch DBC, Diagnose Behandel Combinatie) are applicable to the SAPS guideline:

1450: tendinitis supraspinatus/biceps, i.e., impingement;

1460: rotator cuff/biceps tendon tear.

We excluded the code 1480 “AC/SC disorders” and 1487 “other enthesiopathy of shoulder/elbow.”

The following surgical codes are related:

38100: acromioplasty;

38177 surgery on shoulder bursa.

To examine whether the treatment regimens for SAPS have changed since presentation of this new guideline we extracted data from the Dutch Health Authority (NZA) (Zorgautoriteit Citation2016). After choosing a DRG all declared subsequent surgical procedures can be found and calculated. The NZA is an autonomous administrative authority under the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sports. The NZA has a database with nationwide data of all patients diagnosed at any Dutch hospital, and all interventions such patients underwent within the chosen diagnostic criteria (Zorgautoriteit Citation2018). As stated before, registry in this database is mandatory using a fixed list with diagnoses to choose from. Every Dutch orthopedic surgeon is obliged to use these codes for billing of the costs at the insurance companies.

This list has not been changed during the study period. Only 1 DRG can be chosen for the shoulder complaint at the first visit. This database starts from 2012 and contains only anonymous and aggregated data. We looked within the groups of the above-mentioned DRGs from January 1, 2012 to December 31, 2016 and registered the number of patients who had subsequent surgery. The numbers in the database were complete for 2012, 2013, and 2014. As a result of the ongoing billing process at the time of this study the numbers for the year 2015 were 90% completed and the numbers for 2016 were 75% completed. The numbers of these years are extrapolated to 100% in order to make a valid comparison.

The Dutch healthcare insurance system requires referral by a GP before a patient can visit a medical specialist such as an orthopedic surgeon. To calculate the incidence of DRGs, and thus the trend in referrals by mostly GPs, information was gathered from the Dutch Central Bureau of Statistics (Statline 2018).

Additionally, an online survey (see Supplementary data) was performed with a small cohort of GPs and orthopedic surgeons. GPs were randomly selected from a database of the university and the orthopedic surgeons were selected from the Dutch orthopedic association database. All of the invited GPs (n = 33) and orthopedic surgeons (n = 23) filled in the form. They were asked about their experiences with shoulder complaints, the guideline, and if they changed their treatment strategies as a result of the guideline.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics were used for the annual incidence rates of referred patients for a specific DRG per 100,000 inhabitants. To get an impression of the effect of the dissemination of the guideline, total numbers of DRGs in the Netherlands were calculated and compared with the baseline year (2012) and with each subsequent year. 95% confidence intervals (CI) of the difference between these 2 proportions were calculated (Fleiss et al. Citation2013). SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) was used.

Ethics, funding, and potential conflicts of interest

This study was reviewed and approved by the medical ethical committee of University Medical Center Groningen (register: 201501203-2018/259). There was no special funding for this study and there is no potential conflict of interest to be declared by any of the authors.

Results

Incidence

From 2012 to 2016 a total of 237,960 patients were diagnosed by orthopedic surgeons with DRG 1450 “tendinitis supraspinatus/biceps, i.e., impingement” and 97,900 patients with DRG 1460 “rotator cuff/biceps tendon tear.” In 2016, fewer patients were diagnosed with a tendinitis supraspinatus/biceps, i.e., impingement (DRG 1450) compared with 2012, a decrease of 10%. More patients with rotator cuff or biceps tendon tear (DRG 1460) were diagnosed in 2016 than in 2012, an increase of 32% (). The referral pattern to orthopedic departments changed between 2012 and 2016. For DRG 1450 the incidence decreased from 2.96 to 2.63 per 100,000 inhabitants; for DRG 1460 the incidence increased from 1.06 to 1.38 per 100,000 inhabitants.

Table 1. Numbers and incidences (per 100,000 inhabitants in the Netherlands) of DRG divided by nonoperative and operative treatment

Surgery for DRG 1450 tendinitis supraspinatus/biceps, i.e., impingement

Of the patients diagnosed with DRG, 1,450 14% underwent surgery in 2012. This decreased to 9% in 2016 (). This is a statistically significant drop when comparing 2012 with 2014, 2015, and 2016, but also when comparing the subsequent years with each other ().

Table 2. Differences in patients who had surgery for DRG 1450 (tendinitis supraspinatus/biceps, i.e., impingement) for each year compared with 2012 and subsequent years

Surgery for DRG 1460 rotator cuff or biceps tendon tear

Of the 1,460 patients diagnosed with a DRG, 30% underwent surgery in 2012. The percentage of referred patients who had surgery decreased to 25% in 2016 (). This is a statistically significant drop when comparing 2012 with 2015 and 2016, but also when comparing 2014, 2015, and 2016 with each other ().

Table 3. Differences in patients who had surgery for DRG 1460 (rotator cuff or biceps tendon tear) for each year compared with 2012 and subsequent years

Surgical codes

When looking at surgical codes a statistically significant decrease in acromioplasties (41%) and an increase in bursectomies (18%) is seen over the years ().

Table 4. Surgical procedures

An overview of the percentages of the total referred patients for each DRG treated surgically is depicted in .

To gain an impression of the experiences with the guideline an online survey (see Supplementary data) was performed on shoulder surgeons and GPs. 23 shoulder surgeons and 33 GPs were reached. All but 2 shoulder surgeons were familiar with the guideline and 19 considered it helpful with treating their patients with SAPS; 19 surgeons stated that less than 10% of the SAPS patients were treated surgically after the guideline was published.

2 out of 33 GPs were familiar with the SAPS guideline but 11 of the GPs stated that they had changed their treatment the past years; more patients are treated nonoperatively and not referred to an orthopedic specialist.

Discussion

This study was conducted to investigate the effect of the introduction of the Clinical Practice Guideline for Subacromial Pain Syndrome. The results show that after publication of the guideline, the number of patients referred with the diagnosis of “impingement” or “tendinitis” decreased by 10%. Surgery decreased, by 37% and 17% respectively, in the SAPS and rotator cuff tear-related group. The proportion of surgical treatment for “tendinitis” and “rotator cuff tear” decreased from 18% in 2012 to 15% in 2016. Also, a decrease in acromioplasties was observed. Despite most GPs not being familiar with the SAPS guideline they had changed their practice with fewer referrals.

Our results are in line with international shifts in the treatment of SAPS and rotator cuff tears, most likely as a result of emerging evidence. In Finland a drop in acromioplasties is seen from 1998 to 2011 (Paloneva et al. Citation2015). In Australia the number of patients having a rotator cuff repair increased over the years 2001–2013 (Thorpe et al. Citation2016). The same trend is seen in the United States, with a decrease in acromioplasties and a rise in rotator cuff surgeries (Mauro et al. Citation2012). The international rise in patients undergoing surgical repair for a rotator cuff tear may be the result of improved surgical options during the latest 15 years.

The Clinical Practice Guideline for Diagnosis and Treatment of Subacromial Pain Syndrome was completed in 2012. Since 2012 more scientific evidence supports the recommendations of the Clinical Practice Guideline. The most recent RCT with surgical, sham surgical, and nonoperative treatments for SAPS showed no benefit of surgery (Beard et al. Citation2018). The RCT of Farfaras et al. (Citation2016) showed no difference between open acromioplasty, arthroscopic acromioplasty, and physiotherapy in the treatment of SAPS after 2–3 years, but somewhat better results for the surgical groups compared with the physiotherapy group after long-term follow-up (Farfaras et al. Citation2018). Ketola et al. (Citation2017) saw no benefit of surgical treatment for SAPS after 10 years follow-up of an RCT. A review of 2014 saw a benefit of physiotherapy compared with controls (Gebremariam et al. Citation2014).

Several recent RCTs showed no benefit of surgery for asymptomatic degenerative rotator cuff tears compared with nonoperative treatment (Moosmayer et al. Citation2014, Lambers Heerspink et al. Citation2015). No difference was seen either when these treatments were combined with an acromioplasty (Kukkonen et al. Citation2015).

Several institutes have recognized elements that increase the impact of clinical guidelines, like the standards of trustworthiness developed by the IOM (Institute of Medicine) of the American National Academies, and derivative products like physician–patient guides that help provide more practical information. The Dutch guideline fulfills these conditions. Nevertheless, several clinical guidelines like those produced by NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) in the UK and other national bodies appear to play a limited part in orthopedic decision-making (Grove et al. Citation2016).

Although formal codified knowledge in the form of clinical guidelines still appears to play a modest part in orthopedic surgery clinical practice decision-making, the coincidence of new high-level scientific evidence provided by well-designed and performed RCTs and the development of clinical guidelines will have an impact on orthopedic clinical decision-making (Khan et al. Citation2013). We observed this effect in our study period after implementation of our clinical guideline and the publication of several RCTs that confirmed the conclusions of our guideline.

The results of the survey show that the treatment strategies of the orthopedic surgeons are roughly in line with the guidelines; fewer patients were treated surgically. However, only 2 out of 33 GPs were familiar with the SAPS guideline. All GPs used the National General Practitioner Guideline (NHG) “shoulder complaints” from 2008. We found a decline in referrals from GPs, but still it is unclear whether this can be attributed to the guideline.

Clinical orthopedic practice is difficult to change, as shown in our study: SAPS is still treated surgically in 10% of cases. This is also seen in the treatment of degenerative meniscal tears. Several studies and clinical guidelines indicate that arthroscopic debridement is of no benefit (Sihvonen et al. Citation2013, Thorlund et al. Citation2015) but arthroscopies on patients with degenerative meniscal tears are still performed in the Netherlands (Rongen et al. Citation2018).

One of the flaws is that the data of this study were derived from the database of the NZA, which started in 2012 with no information preceding that. The effects we found may be the result of a trend based on earlier reports. Another limitation is the extrapolation of the database numbers for 2015 and 2016 to compare them with the preceding years. Although this may influence the total number of patients with that diagnosis, the relative number of surgical vs. nonoperative treatments is not influenced because this is only recorded within the diagnostic group. The surgical codes are used for a sole procedure or as part of other surgery, such as arthroscopic lateral clavicular resection, therefore the numbers are not always limited to DRG 1450 and 1460 but may also be registered from other DRGs. On the basis of registration inaccuracies, a distal clavicle resection could have been performed additional to an acromioplasty, or vice versa. As the aim of the study was to identify the number of procedures before and after the publication of the guideline, and the registration system did not change, this will not have had an effect on the study results.

In summary, the introduction and dissemination of this guideline seem to have contributed to implementation of more appropriate healthcare and prevention of unnecessary surgeries. Although GPs refer fewer patients for SAPS, their education can still be improved.

Supplementary data

The online survey is available as supplementary data in the online version of this article, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/ 17453674.2019.1593641

EV, MS, CK, and RD all participated in the conception and design of the study. EV was responsible for acquisition of the data. EV and MS did the statistical analysis. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version of the manuscript.

The authors would like to thank thank Roy Stewart and Ruth Rose for their contribution to the study and the analysis.

Acta thanks Lars Evert Adolfsson and Jeppe Vejlgaard Rasmussen for help with peer review of this study.

Supplementary Material

Download PDF (34.9 KB)- Beard D J, Rees J L, Cook J A, Rombach I, Cooper C, Merritt N, Shirkey B A, Donovan J L, Gwilym S, Savulescu J. Arthroscopic subacromial decompression for subacromial shoulder pain(CSAW): a multicentre, pragmatic, parallel group, placebo-controlled, three-group, randomised surgical trial. Lancet 2018; 391(10118): 329–38.

- Björnsson Hallgren, H C, Adolfsson, L E, Johansson K, Öberg B, Peterson A, Holmgren T M. Specific exercises for subacromial pain: good results maintai[multidata]|Japan Society for the Promotion of Science|Japan Society for the Promotion of Science London|ned for 5 years. Acta Orthop 2017, 88(6), 600–5.

- Diercks R L. Practice guideline “diagnosis and treatment of the subacromial pain syndrome.” Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2014a; 158: A6985.

- Diercks R, Bron C, Dorrestijn O, Meskers C, Naber R, de Ruiter T, Willems J, Winters J, van der Woude, Henk Jan. Guideline for diagnosis and treatment of subacromial pain syndrome: a multidisciplinary review by the Dutch Orthopaedic Association. Acta Orthop 2014b; 85(3): 314–22.

- Dorrestijn O, Stevens M, Winters J C, van der Meer K, Diercks R L. Conservative or surgical treatment for subacromial impingement syndrome? A systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2009; 18(4): 652–60.

- Farfaras S, Sernert N, Hallström E, Kartus J. Comparison of open acromioplasty, arthroscopic acromioplasty and physiotherapy in patients with subacromial impingement syndrome: a prospective randomised study. KSSTA 2016; 24(7): 2181–91.

- Farfaras, S, Sernert N, Rostgard-Christensen L, Hallstrom E, Kartus J T. Subacromial decompression yields a better clinical outcome than therapy alone: a prospective randomized study of patients with a minimum 10-year follow-up. J Sports Med 2018; 46(6): 1397–407.

- Fleiss J L, Levin B, Paik M C. Statistical methods for rates and proportions. Chichester: Wiley; 2013.

- Gebremariam L, Hay E M, van der Sande R, Rinkel W D, Koes B W, Huisstede B M. Subacromial impingement syndrome: effectiveness of physiotherapy and manual therapy. Br J Sports Med 2014; 48(16): 1202–8.

- Greving K, Dorrestijn O, Winters J C, Groenhof F, Van der Meer K, Stevens M, Diercks R L. Incidence, prevalence, and consultation rates of shoulder complaints in general practice. Scand J Rheumatol 2012; 41(2): 150–5.

- Grove A, Johnson R, Clarke A, Currie G. Evidence and the drivers of variation in orthopaedic surgical work: a mixed method systematic review. Health Syst Policy Res 2016; 3: 1.

- Ketola S, Lehtinen J T, Arnala I. Arthroscopic decompression not recommended in the treatment of rotator cuff tendinopathy: a final review of a randomised controlled trial at a minimum follow-up of ten years. Bone Joint J 2017; 99(6): 799–805.

- Khan H, Hussain N, Bhandari M. The influence of large clinical trials in orthopedic trauma: do they change practice? J Orthop Trauma 2013; 27(12): e274.

- Kukkonen J, Joukainen A, Lehtinen J, Mattila K T, Tuominen E K, Kauko T, Aarimaa V. Treatment of nontraumatic rotator cuff tears: a randomized controlled trial with two years of clinical and imaging follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2015; 97(21): 1729–37.

- Lambers Heerspink F O, van Raay J J, Koorevaar R C, van Eerden P J, Westerbeek R E, van ’t Riet E, van den Akker-Scheek I, Diercks R L. Comparing surgical repair with conservative treatment for degenerative rotator cuff tears: a randomized controlled trial. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2015; 24(8): 1274–81.

- Luime J J, Koes B W, Hendriksen I, Burdorf A, Verhagen A P, Miedema H S, Verhaar J. Prevalence and incidence of shoulder pain in the general population: a systematic review. Scand J Rheumatol 2004; 33(2): 73–81.

- Mauro C S, Jordan S S, Irrgang J J, Harner C D. Practice patterns for subacromial decompression and rotator cuff repair: an analysis of the American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery database. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012; 94(16): 1492–9.

- Moosmayer S, Lund G, Seljom U S, Haldorsen B, Svege I C, Hennig T, Pripp A H, Smith H. Tendon repair compared with physiotherapy in the treatment of rotator cuff tears: a randomized controlled study in 103 cases with a five-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2014; 96(18): 1504–14.

- Neer C S. Impingement lesions. Clin Orthop Rel Res 1983; (173): 70–7.

- Paloneva J, Lepola V, Karppinen J, Ylinen J, Aarimaa V, Mattila V M. Declining incidence of acromioplasty in Finland. Acta Orthop 2015; 86(2): 220–4.

- Papadonikolakis A, McKenna M, Warme W, Martin B I, Matsen III F A. Published evidence relevant to the diagnosis of impingement syndrome of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011; 93(19): 1827–32.

- Rongen J J, van Tienen T G, Buma P, Hannink G. Meniscus surgery is still widely performed in the treatment of degenerative meniscus tears in the Netherlands. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2018; 26(4): 1123–9.

- Sihvonen R, Paavola M, Malmivaara A, Itälä A, Joukainen A, Nurmi H, Kalske J, Järvinen T L. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy versus sham surgery for a degenerative meniscal tear. N Engl J Med 2013; 369(26): 2515–24.

- Statline C. Centraal bureau voor de statistiek. Bevolking kerncijfers Identifier: 37296ned, http://opendata.cbs.nl/statline

- Thorlund J B, Juhl C B, Roos E M, Lohmander L S. Arthroscopic surgery for degenerative knee: systematic review and meta-analysis of benefits and harms. BMJ 2015; 350: h2747.

- Thorpe A, Hurworth M, O’Sullivan P, Mitchell T, Smith A. Rising trends in surgery for rotator cuff disease in Western Australia. Aust NZ J Surg 2016; 86(10): 801–4.

- Urwin M, Symmons D, Allison T, Brammah T, Busby H, Roxby M, Simmons A, Williams G. Estimating the burden of musculoskeletal disorders in the community: the comparative prevalence of symptoms at different anatomical sites, and the relation to social deprivation. Ann Rheum Dis 1998; 57(11): 649–55.

- Zorgautoriteit. Open Data Van De Nederlandse Zorgautoriteit 2016; http://www.opendisdata.nl

- Zorgautoriteit. 2018; https://www.nza.nl/english

Questionnaire

How many patients with shoulder complaints are seen on a weekly base.

□ < 5 patients, □ 5–10 patients, □ 10–20 patients, □ > 20 patients

How many years have you worked as an orthopedic surgeon or GP?

□ < 5 years, □ 5–10 years, □ 10–20 years, □ > 20 years

What percentage of the patients with a SAPS do you treat operatively or refer for surgery?

□ 0–10%, □ 10–20%, □ 20–30%

Have you changed your treatment strategy recently?

□ Yes, I have treated more patients with conservative treatment

□ Yes, I have treated or referred more patients with surgical treatment

□ No, I have not changed my strategy

Are you familiar with the SAPS guideline?

□ Yes, □ No

If no, do you use another guideline?

□ Yes, □ No

□ General Practitioner Guideline Shoulder Complaints 2008 (NHG standaard), □ NICE guideline

Do you consider the SAPS guideline helpful in treating your patients?

□ Yes, □ Neutral, □ No