ABSTRACT

Background

There was insufficient understanding of how art therapists experience their work with people with psychosis-related diagnoses, and of their practice development.

Aims

To understand art therapists’ perceived practise and its development regarding psychosis.

Methods

Within a grounded theory framework, interviews and a focus group carried out in the years 2015–2017 elicited the experiences of 18 UK-based art therapists, working in a range of National Health Service (NHS) contexts, concerning art therapy in relation to psychosis and how they developed their current practice. Audio-recordings were transcribed verbatim and analysed to build theory.

Results

The grounded theory proposes how practice and its development intertwine. Training confers resilience but therapists learn greatly from their clients, enhancing their ability for alliance-building. Therapists’ early struggles also spur further training. Skills for trauma are helpful. Clients may become stuck or disengage, and/or develop through ongoing engagement with art and the art therapist, who supports their journey. The service and wider societal contexts impact the art therapist's work through their effect on clients and/or the art therapist's ability to attune to clients.

Conclusions

The findings concur with previous research regarding common therapeutic factors, especially the alliance, and on other therapists’ practice development.

Implications for practice and research

Understanding therapy processes should incorporate service and societal influences on therapist and client. Training needs to include understanding adversity and trauma, and working with trauma.

Plain-language summary

People who receive a diagnosis of psychosis or schizophrenia are sometimes offered art therapy. However, we did not know enough about exactly what art therapists do. It was also important to understand how art therapists come to know what helps people in art therapy. Art therapy training has to cover many things, not only psychosis, so art therapists learn their skills in various ways.

Through interviews and a focus group we talked to 18 UK-based art therapists working in different NHS contexts and digitally recorded the discussions. We made written records of what was said, and analysed these to create a theory of how art therapists work with people who have been given a diagnosis of psychosis or schizophrenia across inpatient and outpatient settings. Our theory proposes that art therapists’ training makes them quite resilient. However, they learn vital things from their clients. This especially helps them to become better at building a helpful relationship with each client.

Some art therapists also seek further training when they are newly qualified, especially if they run into difficulties when trying to help a client. Some art therapists find it helpful to have skills for supporting people who have experienced past trauma. Clients develop through art-making and talking with the art therapist. Art therapists find it easier to do their work with clients if the service they work in is supportive.

Our theory fits in with previous research, which says that building a good relationship with clients makes an important difference to the outcome in different kinds of therapies. Our theory also fits in with previous research on how other therapists develop their skills.

Future research on art therapy should include looking at the service where the therapist works, and how it may affect both therapists and clients. Art therapy training needs to include trauma-related work.

Introduction

Art therapists have worked with people with psychosis-related diagnoses for several decades (Adamson, Citation1984; Lyddiatt, Citation1972; Naumburg, Citation1950; Wadeson & Carpenter, Citation1976), starting before the founding of the UK and USA art therapists’ professional associations in 1964 and 1969 respectively. The UK's National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE, Citation2014, Citation2017) recommends cognitive behaviour therapy for psychosis (CBT-p), as well as considering offering supportive arts therapies.

Art therapy (group or one-to-one) uses art-making as a vehicle for therapeutic work within the therapeutic relationship. A survey by Patterson et al. (Citation2011) suggested that most UK art therapists working with people diagnosed with psychosis worked psychodynamically. Within this broad approach, a strong emphasis on transference and a ‘non-directive’ therapist stance was central between the 1980s and 2000 in UK art therapy training (Wood, Citation1997). However, earlier post-WWII art therapists focussed on expression (Adamson, Citation1984) and then on humanistic and supportive group approaches (Greenwood & Layton, Citation1987). Recently, art therapy practice has been influenced by more structured approaches such as mentalization-based therapy, compassion focussed therapy, dialectical behaviour therapy and CBT as art therapists in the UK and USA accommodated new evidence and theory, and changing economic circumstances for services (Franks & Whitaker, Citation2007; Joseph & Bance, Citation2019; Verfaille, Citation2011; Wood, Citation2011). Additionally, since 2000 there is a broader interest in the therapeutic potential of art-making and viewing (Maclagan, Citation2005; Moon, Citation2007, Citation2010).

Three randomised, controlled trials have suggested that group art therapy can benefit people with psychosis-related diagnoses, both as inpatients Montag et al. (Citation2014) and outpatients (Green et al., Citation1987; Richardson et al., Citation2007). A large trial of outpatient art therapy (Crawford et al., Citation2012), known by the acronym MATISSE (Multicentre study of Art Therapy in Schizophrenia: Systematic Evaluation), suggested no additional benefit for people with schizophrenia diagnoses compared to activity groups or usual care. However, it suffered from low attendance in both treatment and active control arms, which may have made the ‘intention-to-treat’ analysis too conservative (Hernán & Hernández-Diaz, Citation2012).

There is evidence for some overlap of process and outcome between art therapy and CBT-p. Patterson et al. (Citation2013) reported that MATISSE trial participants who engaged in art therapy experienced art-making as ‘relaxing and enabling contact with others without feeling overwhelmed’ (Patterson et al., Citation2013, p. 6). They also set goals with the art therapist, which appears consistent with CBT-p (Sivec & Montesano, Citation2012; Wood et al., Citation2015).

Others theorise that implicit expression of emotion in artwork can enable art therapists to facilitate its verbal articulation and thus enhance cognitive awareness of it, constituting ‘meta-cognitive processes’ (Czamanski-Cohen & Weihs, Citation2016, p. 65). Consistent with this, in a small qualitative study involving participants with a diagnosis of first-episode psychosis (Lynch et al., Citation2019), participants felt that art therapy supported reflection on one's own mind. Meta-cognitive processes like these are core to CBT (Dobson, Citation2013).

Separate personal accounts in Romme (Citation2009a) with different psychotherapies (psychodynamic and CBT) describe voice-hearers’ realisations that their voices represented emotions that they had been previously unable to experience directly. This again may be viewed as a form of metacognitive process, in which service users can integrate their experiences. In these accounts, such integration was part of understanding and learning to manage the impact of childhood trauma (Romme, Citation2009b).

Lysaker and Lysaker (Citation2010) describe clients who experience psychosis as having a reduced sense of self and great anxiety about interacting with others and the world. Fear of interaction was highlighted by Patterson et al. (Citation2013) as a barrier to attending group art therapy. It is consistent with the need for CBT-p therapists to attend to the therapeutic alliance (Sivec & Montesano, Citation2012), and art therapists to create safety through the triangular relationship between client, artwork and therapist (Czamanski-Cohen & Weihs, Citation2016; Gabel & Robb, Citation2017; Lynch et al., Citation2019). High consensus art therapy practices relating to psychosis in the Delphi survey of Holttum et al. (Citation2017) included attention to the alliance and recognition of clients’ coping strategies, again echoing CBT-p components (Sivec & Montesano, Citation2012).

Shared therapeutic mechanisms featured in a review of meta-analyses of different therapies in relation to anxiety and depression, with three mechanisms accounting for substantial outcome variation: therapist belief in the approach, therapeutic alliance, and therapist characteristics (Budd & Hughes, Citation2009). There is little research on therapist characteristics for art therapists, but interviews with 100 USA-based psychotherapists and counsellors (Rønnestad & Skovholt, Citation2003), suggested that feedback from clients provides crucial impetus to ongoing practice development. More experienced therapists reported practising less rigidly, with an enhanced ability for alliance-building. Whilst Rønnestad and Skovholt (Citation2003) do not provide direct evidence that professional development affects client outcome, it could be significant.

It has also been suggested that supervision is crucial to trainee psychotherapists’ competency development (Callahan et al., Citation2009; Watkins, Citation2013), and a survey of 357 qualified UK clinical psychologists provides some support for this (Nel et al., Citation2012). Based on the self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, Citation2002), supervision could contribute to environments that allow therapists to experience competence, autonomy and relatedness to others and foster personal and professional development.

Several studies suggest that employees with these needs met report higher self-esteem and wellbeing (Baard et al., 2000, cited in Ryan & Deci, Citation2002; Ilardi et al., Citation1993), and less compassion fatigue (McCaffrey & McConnell, Citation2015; Sinclair et al., Citation2016). Concerning art therapists, Feen-Calligan (Citation2012) suggests there may be challenges to their professional identity development given the relatively sparse evidence base for art therapy, and limited jobs.

Notwithstanding the apparent therapeutic overlaps, there have been suggestions that art therapy for psychosis is insufficiently defined (Attard & Larkin, Citation2016; Patterson et al., Citation2011). One element missing from Lynch et al. (Citation2019) was the perspective of art therapists, and participants did not describe what the therapist did. Patterson et al. (Citation2013) consulted art therapists for verification purposes only. Patterson et al. (Citation2011) did not report the length of experience of art therapist participants in working with psychosis and enquired only about practice experience, not its development. Whilst there are art therapist accounts of psychosis-related work (e.g. Killick, Citation1996; Killick & Schaverien, Citation1997), few have constituted systematic research.

Rationale

Whilst some studies have illuminated clients’ experience of art therapy in relation to psychosis, there is a lack of systematic qualitative research on therapist experience. Also, there is a need for greater clarity about what art therapists do and how they come to do it. The interviews reported here formed part of the material drawn upon by Wright and Holttum (Citation2020) in producing new detailed guidelines for art therapy in relation to psychosis, but the findings have not hitherto been reported in detail. Service users were consulted in the production of the Guidelines (Wright & Holttum, Citation2020) but this paper reports only on the interviews with art therapists.

Methods

Participants and design

Grounded theory methodology (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2015; Strauss & Corbin, Citation1990) was used as a systematic qualitative approach for theory-building. Thirteen art therapists were interviewed individually, another 2 as a pair about their work together, and 3 of these 15 also attended a focus group of 6 art therapists who discussed the initial theory created from the data from the other 15, as a form of validation. Participants’ experience of providing art therapy for the client group ranged from 1 to over 20 years, with 13 of the 18 therapists (72%) having done this work for over 15 years. Most participants had practised in different settings: 13 in outpatient services, 10 in acute inpatient, 8 in long-stay in-patient, 5 in ‘early intervention for psychosis’ (EIP), and 4 in inpatient forensic. Seven participants were male and 11 female and all were White. Most had seen clients both one-to-one and in groups. Three participants had private practices as well as the National Health Service (NHS) art therapy.

Procedure

The study received approval from the ethics panel at the Salomons Institute for Applied Psychology, Canterbury Christ Church University. Participants were asked to anonymise clients in interviews. During transcription potentially identifying details were disguised or omitted. For recruitment, an email was sent to all BAAT members, inviting art therapists working with people diagnosed with psychosis and schizophrenia to take part. Those expressing interest were sent the information and consent form. Some confirmed immediately, and others were contacted a week later, and any questions answered.

Theoretical sampling (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1990) was carried out, in that as the interviewing progressed, it seemed important to hear from art therapists in differing contexts so that the applicability of emerging hypotheses could be examined across them. For similar reasons, art therapists were recruited with differing lengths of experience and from a range of service contexts. By the time 18 participants had contributed, no new categories were emerging, suggesting theoretical saturation (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1990).

Interview

A semi-structured interview was used (Robson, Citation2002). Questions covered participants’ experience of art therapy training and practice development, and of working with a client who appeared to benefit from art therapy and one who did not. The definition of ‘benefit’ was left open so as not to impose any specific understanding. Participants were asked how therapy ‘played out’, and to describe what they did and what they observed. Participants were also asked about things that helped or hindered their work.

Data analysis

After transcribing each interview, the lead author read each transcript several times and wrote memos to begin theorising and attempt to make biases explicit and consider their impact. Following this, open coding was carried out. Coding proceeded alongside further interviewing so that lines of questioning could focus on emerging hypotheses. For example, initial interviews did not illuminate the role of art-making. It, therefore, seemed important to add specific questions about how clients used art. After open coding, basic-level codes were grouped into focused codes. Diagramming was used to map individual therapists’ practice development, and individual clients’ trajectories, to examine antecedents and consequences (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1990). Model diagrams were drawn up and re-drawn using constant comparison, whereby the lead author checked back against the raw data.

Quality

Two transcripts and their coding were shown to a second researcher for an independent audit, who confirmed the categories. After 15 art therapists had been interviewed (2 as a pair), a focus group was held with three of those already interviewed and three additional art therapists. Five of these six had over 15 years of experience of working with people with psychosis-related diagnoses in NHS settings, and one had been an NHS art therapist for over 20 years but had less experience with these clients. Focus group members examined the initial model, discussed it, and discussed further examples of their work. The focus group was transcribed and coded, and the model slightly modified, but participants mainly agreed with the categories and their hypothesised interrelationships. Following this, in further respondent validation, the new model was sent with a request for feedback to all 18 participants. Nine provided comments, resulting in further small modifications. This was mainly in terms of category names: For example, the subcategory ‘always there for the client’ was changed to ‘being there for the client’.

The lead author hoped that the independent audit and respondent validation would minimise researcher bias. She is not an art therapist but has always enjoyed art-making, had a sense of it being helpful for expressing confusing feelings, and believed that art therapy may be helpful to many people. She reflected frequently on possible biases in a reflective diary. For example, one entry concerned having expected to find the main function for art-making, and feeling that as interviews progressed, art-making seemed either not prominent, or on probing seemed to have confusingly many functions. Diagramming proved helpful in placing the art-making within each client's therapy trajectory as participants described it.

Results

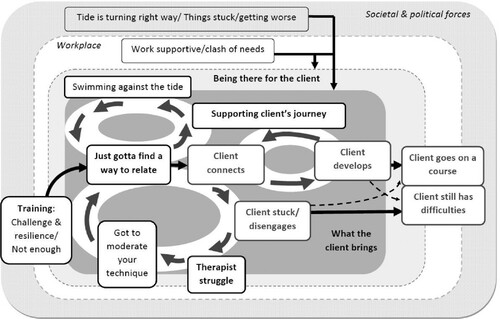

shows the grounded theory depicting the journeys of both therapist and clients and hypothesised bi-directional influences of one on the other. The categories () are illustrated with quotations after first summarising the theory. According to the theory, participants came to art therapy with drive and commitment (swimming against the tide). They experienced training as challenge and developing resilience, and often also as not enough, especially when recently qualified. They experienced struggle with some clients, sometimes realising a need to moderate your technique: from too-rigid allegiance to a specific theory or practice. The key need was to find a way of relating to clients.

Table 1. Main categories and number of therapists for whom each category pertained.

Relating may lead to client connection, usually through or with the help of artwork. Participants’ sense of reward could further spur swimming against the tide of whatever might hinder the work. Client connection in turn may have two different outcomes. It could enable client development, with the art therapist supporting their journey, or the client became stuck or disengaged. The art therapist's struggle when a client seemed stuck may lead them to work to contain their emotions. This, and moderating your technique may lead to finding a new way of relating, and to new client connection and development. Clients who seemed stuck or disengaged may ultimately still have difficulties, but these could also accompany more positive outcomes, represented by the category Client goes on a course. Being there for the client is shown as a containing area within , representing adapting to individual client needs, sticking by them, and learning with every new client.

also shows the workplace context. There was support or a clash of needs between organisation and client, which may affect what the client brings to art therapy as well as the therapist's emotional availability. Therapists experienced societal and political forces as producing at different times a sense of tide turning in the right way in terms of useful policies and practice guidelines, or things being stuck or getting worse.

Swimming against the tide

Several participants referred to art therapists, and a few also to artists as outsiders. This could be in relation to difficulty describing art therapy, or valuing an outsider position or both:

Art therapy and the arts therapies – this whacky thing that actually still is a quite hard sell. (P4, Focus group, line 404)

I think most art therapists are … they still quite like a little bit of an outsider position. (P5 373)

Artists’ core positioning on the edge of things. (P9, 230)

We can't be comfortable in that [outsider] role because we can easily be cut from services. (P5, 374–376)

Being or getting a job that immerses you in psychiatry and then learning to swim against the tide. (P14, Comment in response to draft model in respondent validation (RV) exercise)

Training as challenge and resilience/not enough

Participants talked about training as good grounding psychodynamically and/or for psychosis:

A good grounding in working psychodynamically. My first placement was with a psychosis focus with two art therapists who were 30 years into their careers. (P1, 4)

It gave me confidence to do a bit more. I think I was quite passive before that. (P1, 22–29)

That was the uncertainty for me, ‘cause I never really knew who was gonna turn out to be a long term [inpatient] and who was gonna be only there for that day. (P1, 12)

It was a complete shock to meet a world which was completely unexpected to me and so different. And then it became very interesting. (P2, 30)

I felt I was working with a model that was quite established […]. I’ve since had to adapt it. (P1, 6–8)

When I first trained, I think I would be very, ‘Oh well we have to do this properly, the session's an hour’ […], mistaking the idea of keeping to the frame […] – thinking that that was important above all else. […] And that's a lot due to my inexperience, I think. (P7, 28–30)

What the client brings

Participants described clients in a more holistic way than symptoms or a condition. Most participants described severe difficulties initially:

Voices she could hear, and sometimes in the sessions she’d talk to them. (P3, 78)

He [informal carer] said in her presence that he finds that when she comes back from spending a weekend with her family, she's often much more chaotic and distressed. (P11, 31)

At one point he [client] was worried about benefit sanctions. (P13, 217–218)

We’re circling round whether we might do some trauma work. And actually identifying – the trauma was his first admission. That's it. (P18, 21, focus group)

Therapist struggle

Several participants talked about difficult emotions in response to the work. One participant described great effort to enable a client to lower their defences:

It was a struggle – the whole thing was a struggle. (P3, 119)

Where there is more and more pressure from the organisation to see people short-term, I feel I experience intense guilt […] but that emotion doesn't help in the work with clients. One has to be mentally available and attuned to the work. (P2, 276–280)

If you don't keep it [art-making] up, you’re not going to be in touch with your own processes. […] If I didn't do it I’m sure I’d be unwell. (P9, 248–253)

Just giving myself the permission to make mistakes and to be able to repair them. Use them, try again. (P7, 31)

In the frustrating situations, or distressing, it's important […] to have this kind of [supervisor] support to enable you to put things into context. (P2, 69–70)

As I’ve gone along I’ve pragmatically tried to get supervision and tried to read around things that are trying to grapple with different approaches. (P13, 280–281)

Got to moderate your technique

Many participants, looking back on earlier work, described something like ‘muddling through’ (P3), and advancing from there. Some participants learned from clients’ responses to move away from a too-rigid approach.

Simple reality of what happens when you try to do therapy with people. […] You realise that you’ve got to moderate your technique. (P4, 48–52)

Going from [relative rigidity] to just meeting people at a café and then going for a walk. […] (P10, 76–79)

And because of understanding [the role of trauma], one develops a practice of how you can support people who have been traumatised. (P3, 13)

I realised that the things that people might say, even though on the face of it they might sound quite delusional, were actually incredibly grounded in an emotional reality for them. (P7, 56)

Hearing a music therapist talking about their Open Dialogue work which has been fantastic, getting family dialogues going in music. (P4, 634–5)

Just gotta find a way of relating

Although the training was perceived as a good grounding for applying skills and theories, most also learned from their work with clients that they had just gotta find a way of relating. Partly what seemed to keep them going was the belief in a therapeutic aim and feeling reward at times. Nearly all participants talked about explaining or inviting:

I always describe the setting, the place, and the possibilities [to a new client]. (P2, 25)

Before we even start […] we always look for ways to use art as a grounding technique […] ‘What's your favourite colour? What makes you feel safe?’ (P15, 65–66)

Actually, it's not something terribly fancy that you’ve got to do. You’ve just gotta try and find a way of relating with people. (P4, 156)

The aim and my focus is to try to recreate an object which can hold some [symbolic] content. (P2, 58)

Having more theoretical understanding of [psychosis] and a bit of a model [from reading] helped. […] It focused the work. (P3, 66)

Client connects

The art therapist, by being there, and finding a way of relating, enables clients to connect. Connecting may be with the art materials only, sometimes directly with the therapist, but more usually the latter (and/or other group members) through the former. Participants talked about art assisting verbal expression or being the initial expression, or helping identify experiences that needed attention:

I’m thinking of one particular client whose timeline [in artwork] stopped at this very point at which she became unwell […] and it then transpired that there was – she shared an actual trauma. (P14, 59–61, P14 and 15 interview)

Her pictures expressed a lot of anger, and she was angry at what – she felt these people were persecuting her. (P3, 77)

If I can persuade them to sit and start making some artwork […], after about half an hour or three quarters of an hour they’ll be much more able to talk ordinarily. (P13, 297–300)

She used to do very expressive big drawings with soft pastels, which she loved. (P7, 76–7)

She, over time, told me through her images, and through us reflecting on them together, about her story, her life, her narrative. (P3, 82)

It's a way to relieve themselves or rid themselves of something. (P5, 59)

I felt that she got a chance to look at herself [when reviewing a series of artworks] and was shocked. (P7, 220)

I possibly had made a comment about the artwork […] I don't think I was gentle enough with it. (P6, 199)

She would very rarely make any images in the therapy. […] but we got into a rhythm of her […] sometimes bringing actual images she’d made, sometimes bringing them on her phone, sometimes emailing them to me at work. (P4, 74–76)

Client develops

Most participants talked about clients developing new coping or new perspectives. This represents clients’ perceived move towards greater agency or coping with difficulties, or a small advance:

Eventually she decided to put the picture on the wall – a picture that I had never been able to see properly. (P2, 61)

I wasn't aware there’d been a trauma, so it's only until the timeline [in artwork] […]. And that's something that shifted the client's ability to then start to think about something that was really difficult. (P14, 72–75, P14 and 15 interview)

She also apparently was a bit more aware of people where she lived. […] They’d noticed some of the same thing. (P1, 46)

She had been very paranoid about the neighbours. […] That got moderated into things just being annoying. (P4, 95–96)

[The client] found it helpful to understand her history of mental illness as being something that's arisen on the back of trauma. (P14, 63, P14/15 interview)

Supporting the client's journey

Participants supported clients in understanding their difficulties, sometimes through suggesting making art around relevant themes, and sometimes using psychoeducation:

Those [emotions] will often come through via the art. And then we need to get that into language. (P8, 141–142)

And then the bit of psychoeducation comes in. We all as humans feel anxious, and it's OK. (P15, 490, P14 and 15 Interview)

Speaking to other human beings and writing about other human beings [in case notes and letters] as though they are like you or me. (P13, 352)

Then [client] really just fell in love with painting. […] After a while I helped him link up with a college, and he started going to college and doing [art]. (P11, 118–120)

Client goes on a course

The title of this category comes from several participants specifically mentioning clients going on a course after they understood their difficulties better and became calmer. Clients became calmer over a period of months:

She went on to be much calmer, not shouting; much more containing her anger. (P3, 89–91)

He got to the point when he’d done enough [therapy] and then he went and did this art course. (P11, 123)

He went off to do an art-based course […] more like what other people his age were doing. (P1, 551)

Client is stuck/disengages

Clients could appear to be stuck or would disengage. Often after being stuck something did shift. Sometimes, however, the therapy seemed to end without benefit. Being stuck could be simply a lack of change or a repetitive pattern:

Frequent pattern – she’d come in and she’d be ranting about this, that and the other thing. (P4, 72–85)

He would just be out that door in two seconds after he’d finished the picture. (P12, 179)

Client still has difficulties

This refers to clients ending therapy with difficulties but not necessarily without benefit. One participant stated of a long-term forensic inpatient:

She's still in a unit where she's locked up, and she still has a lot of difficulties. (P7, 49)

Her own perception of her life was that it was ‘all a bit shit’ would be what she would say. (P1, 45)

Being there for the client

The work may be slow, but the art therapist would be there for the client. As well as simple persistence, this includes avoiding mistakes, and re-inviting clients into art therapy when they seem stuck or disengage. This could be described as continual re-statement of support, continuing to listen, or being there week after week when a client is unable to discuss their difficulties:

I stuck with that for a long time, image after image after image of repetitive shapes and colouring in. (P6, 79)

One or two people have been transferred to the inpatients unit and generally I still see them there. (P10, 15)

I felt I had to be very careful of judging when to suggest [art-making]. (P13, 254)

Being really vocal and not being a blank canvass and having that still face. (P15, 353, P14 & 15 interview)

Sometimes if I had something I had noticed in the sessions and I really wanted to address, […] I would wait for an opening. (P7, 156)

I saw her a bit later on [in the inpatient unit], and I said ‘I can see you another time.’ (P7, 185–6)

Finally, they’ve allowed chance to happen [by trying art technique] and they can see something. […] There's a sense of self agency. (P10, 173–175)

Work supporting/clash of needs

The workplace and wider service context could feel supporting but also there often seemed a clash of needs between clients and the organisation. Team working, or other professionals’ actions could support therapist and client, and sometimes this was through showing a client's artwork:

P15 We were in a ward round, and I’d bring in a picture. […] All these really rock-hard people […] were able to really show and express their feelings […] to this person [client]. (P14 and 15, 1173–1189)

I had quite close supervisory contact with the psychotherapy department, which was very supportive. (P2, 33).

I think what patients require of us as therapists is different from what the institution requires of us. (P5, 133)

Bit soul destroying when you go to the ward round and it's still about – it's quite formal and about medication. (P11, 93)

I’ve seen this refusal – psychiatrists’ refusing to talk about the ill effects [of medication], because they’re so anxious that it will stop – the patient will stop taking their meds. (P4, focus group, 306–7)

Tide is turning in the right way/things are stuck/getting worse

A wider context influences both participants’ training and their subsequent work. Participants had awareness of positive changes in society and its institutions:

We presented [service] to the community mental health teams with […] the fact that the NICE guidelines recommend art therapy. (P6, 48)

I think it's more of an awareness […]. At the root cause of most mental distress is trauma […] and that is changing rapidly, the thinking. (P3, 12)

P14: [University name] has done some work about trauma basis and wards. […]

People with psychosis and how they’re treated within the mental health system currently – I think it's an issue. (P1, 91)

Discussion

The art therapists’ accounts of their practice development with people with a psychosis-related diagnosis is consistent with the findings of Rønnestad and Skovholt (Citation2003) for psychotherapists and counsellors more broadly. As in Rønnestad and Skovholt (Citation2003), art therapists tended to feel lacking in confidence early on, with some latching onto certain theories and techniques slightly too rigidly. An interesting finding in the present study was a certain independence (Swimming against the tide), which may be specific to art therapists in that they usually train as artists initially, and artists could also be viewed as outsiders and art therapy as ‘slightly whacky’ (P4). This position can be both a values-based strength, and a risk if art therapy might be ‘cut from services’ (P5).

Also consistent with Rønnestad and Skovholt (Citation2003) was that participants learned greatly from their clients, and through being there, were able to adapt to clients’ changing needs and moderate [their] technique to find a way of relating. This suggests a central role in art therapy for the therapeutic alliance, similarly to CBT-p (Sivec & Montesano, Citation2012) and other psychotherapies (Budd & Hughes, Citation2009). Specific to psychosis, part of moderating your technique could be coming to understand the role of trauma in psychosis, and how ‘symptoms’ can represent clients’ emotional reality, in keeping with Romme (Citation2009a). Good supervision on relevant placements seemed important, echoing the findings of Nel et al. (Citation2012) for clinical psychology training.

What seemed to spur participants to seek further learning was their emotional struggle when a client seemed stuck or disengaged. Budd and Hughes’ (Citation2009) examination of therapy meta-analyses suggests the importance of therapist characteristics, and the present findings also suggest that art therapists may vary in their effectiveness. It appears to depend on the degree to which they receive a ‘good grounding’ (P1) for working with people with a psychosis-related diagnosis and accumulate experience and relevant further learning. Training for trauma work (illustrated by P14/15 using ‘a grounding technique’) also seems increasingly relevant (Read et al., Citation2014; Romme, Citation2009b; Sweeney et al., Citation2016).

Art therapists perceived the organisational context as impacting their work, valuing a supporting workplace, especially team working and clinical supervision. Supervision could help when therapists struggle. The role of clinical supervision for qualified therapists is little investigated but may be crucial when clients have a psychosis-related diagnosis. This is consistent with Ryan and Deci’s (Citation2002) theorising about psychologically healthy environments. Pressure for shorter work could mean therapists were less ‘mentally available and attuned’ (P2), as were other instances of a perceived clash of needs between ‘the institution’ and ‘patients’ (P5). The present study also extends contextual influences to wider society, for example socio-economic and political issues and national guidelines.

The constructed grounded theory includes feedback loops to illustrate practice development as ongoing, dynamic, and intertwined with client work. Client connection could be followed by client developing or seeming stuck or disengaging. What seemed to make the difference could include clients’ responses to their artwork, a therapist intervention, circumstances outside therapy, and/or clients’ level of distress.

The art therapist's persistent effort to enable clients to feel safe (being there) seems consistent with evidence that people with a psychosis-related diagnosis may be fearful due to previous detrimental interactions including childhood abuse (Read et al., Citation2014). The theme of feeling safe to interact was part of service users’ experience of art therapy in Lynch et al. (Citation2019), and Patterson et al. (Citation2013). It features in theorising about art therapy more generally (Czamanski-Cohen & Weihs, Citation2016; Gabel & Robb, Citation2017). Finding a way of relating seemed to entail belief in a therapeutic aim, which is consistent with another non-specific therapy factor (Budd & Hughes, Citation2009).

When clients seemed to be developing, the art therapist would support their journey, which fits Patterson et al.’s (Citation2013) reporting that clients of the MATISSE trial who engaged had set goals with their art therapist, and is consistent with CBT-p (Sivec & Montesano, Citation2012). A commonly reported immediate response to art-making was calming, and this could be what enabled clients to talk about difficulties, enabling development. Feeling calmer over time was also described, as was going on a course, which stands for various forms of increased social interactions. This aligns with positive outcomes of randomised trials (Green et al., Citation1987; Montag et al., Citation2014; Richardson et al., Citation2007).

Limitations

Our sample was small and lacked ethnic diversity, but participating art therapists worked in different NHS trusts and services. It is also possible that the lead author imposed preconceptions during interviews and analysis. However, an independent researcher viewed two transcripts and their coding, and several participants viewed and fed back on the model, which was also discussed in the focus group. The main changes were modifying some category names. One focus group participant felt that iatrogenic harm such as over-medication was not sufficiently prominent. However, the category Clash of needs seemed to better fit the data, given that interviewees rarely named harm as such. Finally, the present research was only from therapists’ viewpoint. Nevertheless, the interviewer specifically asked about both negative and positive outcomes, and helpful and hindering influences on practice, and these appear to have been captured. Analysis and theory-building was systematic and included attention to reflexivity and respondent validation (Mays & Pope, Citation2000).

Practice implications

The findings suggest the importance of clinical supervision from experienced professionals, in keeping with NICE (Citation2014) and trauma-informed care (Sweeney et al., Citation2016). Also, art therapy training programmes might continue to develop their facilitation of consultation with service users as experts by experience, as advised by the UK's Health and Care Professions Council’s (Citation2017). Understanding the role of childhood trauma and other adversities in psychosis is important (Read et al., Citation2014; Romme, Citation2009b), as are skills for working with people with trauma experiences.

The influence of societal forces needs coverage during training, given that adversities contribute to mental health difficulties (Felitti et al., Citation1998; Marmot, Citation2020), and the evidence that having a diagnosis of ‘schizophrenia’ appears to be associated with receiving insufficient support and services (Schizophrenia Commission, Citation2012, Citation2017). The higher levels of people from BAME (Black and minority ethnic) backgrounds diagnosed with psychosis and their relative lack of access to psychological therapies is also a concern (NICE, Citation2014): Art therapy and art therapy training may need attention to its diversity and cultural competency.

Services may note the importance participants attributed to workplace support. Art therapists worked to address their struggles, but the context may facilitate this. Although some service users reportedly enhanced their social participation, some might need substantive support to do so. This appeared to be a contextual availability in three randomised controlled trials with positive art therapy outcomes compared to usual care (Green et al., Citation1987; Montag et al., Citation2014; Richardson et al., Citation2007), consistent with participants’ support for the client's journey. Goal setting was also a feature of art therapy for those reported to engage and thrive in the MATISSE trial (Patterson et al., Citation2013).

Future research

The present study is unusual in specifically including client dropout and lack of progress. Dropout is a problem for every psychological therapy, and it may be possible to optimise the potential for sustained engagement by understanding it better. In the present study, stasis and disengagement were not always followed by the poor outcome, but sustained engagement appeared to enable calming, increased agency, new perspectives, and increased social participation. Research into engagement should not focus only on sessions but might require attention to service context, and clients’ home and community environments. This may require mixed-methods and longitudinal realist research (Pawson, Citation2013) to track vicissitudes in engagement. Another issue for research could be to use a broader range of outcome measures, including those designed to capture metacognition and emotion awareness (Czamanski-Cohen & Weihs, Citation2016).

Conclusion

This is the first systematic qualitative study of mainly very experienced art therapists’ perceptions of their practice with people with a psychosis-related diagnosis, as well as their perceived practice development. The study adds to previous research on therapist development. It also offers an understanding of how people with a psychosis-related diagnosis may use art, within a supportive therapeutic relationship, to calm themselves and express things that can then be available for discussion. This may increase their agency, self-understanding and social participation. The findings are consistent with NICE’s (Citation2014) recommendation of offering supportive arts therapies to people with a psychosis-related diagnosis. They also provide unique insights into disengagement, which needs further research in most psychotherapies. Given the likely contribution of context, more research is needed on this so that art therapy, and other therapies, may be provided in circumstances most conducive to maintenance of engagement and efficacy.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sue Holttum

Dr Sue Holttum is an applied psychologist working four days per week as a senior lecturer at the Salomons Institute for Applied Psychology, Canterbury Christ Church University, and one day per week as the British Association of Art Therapists’ research officer. Sue teaches research methods and supervises clinical psychology doctorate research and PhDs on psychological therapies, staff support and development, and mental health recovery. Sue draws on personal experience of receiving mental health services in her work, and works with the Salomons Group of Experts by experience.

Tim Wright

Tim Wright has worked as an art therapist in National Health Service mental health services since 1995 and since 2013 has been head of arts therapies for Local Services, West London NHS Trust, where his clinical work is in the areas of psychosis and personality disorder. He teaches on art therapy courses in the UK and abroad and has published several articles on art therapy and mental health problems. From 2008 to 2014 Tim was editor in chief of the International Journal of Art Therapy: Inscape and from 2014 to 2020 served as chair of the British Association of Art Therapists. He chaired the working group for the British Association of Art Therapists guidelines: ‘Art Therapy for People with a Psychosis-Related Diagnosis’ (2020). His latest publications are: ‘Reaching a UK Consensus on Art Therapy for people with a Diagnosis of a Psychotic Disorder Using the Delphi Method’: International Journal of Art Therapy: Inscape 22 (1) 2017 and ‘Art Therapy in a Crisis Resolution/Home Treatment Team: Report on a Pilot Project’: International Journal of Art Therapy: Inscape 22(3) 1–17 April 2017.

Chris Wood

Chris Wood (PhD) works with the Art Therapy Northern Programme a base for art therapy training and research, within Sheffield Health and Social Care Trust and Leeds Beckett University. She is a research fellow with the University of Sheffield and feels fortunate to combine work in education and NHS art therapy. She has published several papers and the book Navigating Art Therapy (2011). She contributed to the BAAT Guidelines on the ways people with a psychosis-related diagnosis use art therapy. Two recent papers (for 2020) concern Art Therapy and the Hearing Voices Movement. She is particularly interested in collaborative ways of working and has learnt much about collaborative approaches from service-user movements. [email protected]

References

- Adamson, E. (1984). Art as healing. Coventure.

- Attard, A., & Larkin, M. (2016). Art therapy for people with psychosis: A narrative review of the literature. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(11), 1067–1078. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30146-8

- Budd, R., & Hughes, I. (2009). The Dodo Bird Verdict-controversial, inevitable and important: A commentary on 30 years of meta-analyses. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 16(6), 510–522. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.648

- Callahan, J. L., Almstrom, C. M., Swift, J. K., Borja, S. E., & Heath, C. J. (2009). Exploring the contribution of supervisors to intervention outcomes. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 3(2), 72–77. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014294

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. L. (2015). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (4th ed.). Sage.

- Crawford, M. J., Killaspy, H., Barnes, T. R., Barrett, F., Byford, S., Clayton, K., Dinsmore, J., Floyd, S., Hoadley, A., Johnson, T., Kalaitzaki, E., King, M., Leurent, B., Maratos, A., O’Neill, F. A., Osborn, D. P., Patterson, S., Soteriou, T., Tyrer, P., & Waller, D. (2012). Group art therapy as an adjunctive treatment for people with schizophrenia: Multicentre pragmatic randomised trial. BMJ, 344(feb28 4), e846. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e846

- Czamanski-Cohen, J., & Weihs, K. L. (2016). The bodymind model: A platform for studying the mechanisms of change induced by art therapy. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 51, 63–71. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2016.08.006

- Dobson, K. S. (2013). The science of CBT: Toward a metacognitive model of change? Behavior Therapy, 44(2), 224–227. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2009.08.003

- Evans, C., Mellor-Clark, J., Margison, F., Barkham, M., Audin, K., Connell, J., & McGrath, G. (2009). CORE: Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation. Journal of Mental Health, 9(3), 247–255. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/jmh.9.3.247.255 doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/713680250

- Feen-Calligan, H. R. (2012). Professional identity perceptions of dual-prepared art therapy graduates. Art Therapy, 29(4), 150–157. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2012.730027

- Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8

- Franks, M., & Whitaker, R. (2007). The image, mentalization and group art psychotherapy. International Journal of Art Therapy, 12(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17454830701265188

- Gabel, A., & Robb, M. (2017). (Re)considering psychological constructs: A thematic synthesis defining five therapeutic factors in group art therapy. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 55, 126–135. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2017.05.005

- Green, B. L., Wehling, C., & Talsky, G. J. (1987). Group art therapy as an adjunct to treatment for chronic outpatients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry, 38(9), 988–991. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.38.9.988

- Greenwood, H., & Layton, G. (1987). An out-patient art therapy group. Inscape: The Journal of the British Association of Art Therapists. Summer issue: 12–19.

- Health and Care Professions Council. (2017). Your duties as an education povider: Standards of education and training guidance. https://www.hcpc-uk.org/globalassets/resources/guidance/standards-of-education-and-training-guidance.pdf

- Hernán, M. A., & Hernández-Diaz, S. (2012). Beyond the intention-to-treat in comparative effectiveness research. Clinical Trials: Journal of the Society for Clinical Trials, 9(1), 48–55. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1740774511420743

- Holttum, S., Huet, V., & Wright, T. (2017). Reaching a UK consensus on art therapy for people with a diagnosis of a psychotic disorder using the Delphi method. International Journal of Art Therapy, 22(1), 35–44. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2016.1257647

- Ilardi, B. C., Leone, D., Kasser, T., & Ryan, R. M. (1993). Employee and supervisor ratings of motivation: Main effects and discrepancies associated with job satisfaction and adjustment in a factory setting. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 23(21), 1789–1805. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1993.tb01066.x

- Joseph, M., & Bance, L. O. (2019). A pilot study of compassion-focused visual art therapy for sexually abused children and the potential role of self-compassion in reducing trauma-related shame. Indian Journal of Health and Wellbeing, 10(10–12), 368–372.

- Killick, K. (1996). Unintegration and containment in acute psychosis. British Journal of Psychotherapy, 13(2), 232–242. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0118.1996.tb00879.x

- Killick, K., & Schaverien, J. (1997). Art, psychotherapy and psychosis. Routledge.

- Lyddiatt, E. M. (1972). Spontaneous painting and modelling – a practical approach in therapy. St Martin’s Press.

- Lynch, S., Holttum, S., & Huet, V. (2019). The experience of art therapy for individuals following a first diagnosis of a psychotic disorder: A grounded theory study. International Journal of Art Therapy, 24(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2018.1475498

- Lysaker, P. H., & Lysaker, J. T. (2010). Schizophrenia and alterations in self-experience: A comparison of 6 perspectives. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 36(2), 331–340. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbn077

- Maclagan, D. (2005). Re-imagining art therapy. Inscape: The Journal of the British Association of Art Therapists, 10(1), 23–30.

- Marmot, M. (2020). Health equity in England: The Marmot review 10 years on. BMJ, 368, m693. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m693

- Mays, N., & Pope, C. (2000). Qualitative research in health care: Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ, 320(7226), 50–52. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.320.7226.50

- McCaffrey, G., & McConnell, S. (2015). Compassion: A critical review of peer-reviewed nursing literature. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 24(19-20), 3006–3015. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12924

- Montag, C., Haase, L., Seidel, D., Bayer, M., Gallinat, J., Herrmann, U., & Dannecker, K. (2014). A pilot RCT of psychodynamic group art therapy for patients in acute psychotic episodes: Feasibility, impact on symptoms and mentalising capacity. PLOS ONE, 9(11), e112348. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0112348

- Moon, C. H. (2007). Studio art therapy. Jessica Kingsley.

- Moon, C. H. (2010). Materials and media in art therapy: Critical understanding of diverse artistic vocabularies. Routledge.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2014). Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: Prevention and management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG178

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2017). Appendix A: Summary of evidence from surveillance. 4-year surveillance (2017). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg178/evidence/appendix-a-summary-of-evidencefrom-surveillance-pdf-4661271326

- Naumburg, M. (1950). Schizophrenic art: Its meaning in psychotherapy. Grune and Stratton.

- Nel, P. W., Pezzolesi, C., & Stott, D. J. (2012). How did we learn best? A retrospective survey of clinical psychology training in the United Kingdom. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 68(9), 1058–1073. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.21882

- Patterson, S., Borschmann, R., & Waller, D. E. (2013). Considering referral to art therapy: Responses to referral and experiences of participants in a randomised controlled trial. International Journal of Art Therapy, 18(1), 2–9. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2012.738425

- Patterson, S., Crawford, M. J., Ainsworth, E., & Waller, D. (2011). Art therapy for people diagnosed with schizophrenia: Therapists’ views about what changes, how and for whom. International Journal of Art Therapy, 16(2), 70–80. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2011.604038

- Pawson, R. (2013). The science of evaluation: A realist manifesto. Sage.

- Read, J., Fosse, R., Moskowitz, A., & Perry, B. (2014). The traumagenic neurodevelopmental model of psychosis revisited. Neuropsychiatry, 4(1), 65–79. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2217/npy.13.89

- Richardson, P., Jones, K., Evans, C., Stevens, P., & Rowe, A. (2007). Exploratory RCT of art therapy as an adjunctive treatment in schizophrenia. Journal of Mental Health, 16(4), 483–491. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09638230701483111

- Robson, C. (2002). Real world research (2nd ed.). Blackwell.

- Romme, M. (2009a). Psychotherapy with hearing voices. In M. Romme, S. Escher, J. Dillon, D. Corstens, & M. Morris (Eds.), Living with voices: 50 stories of recovery (ch 8, pp. 86–94). PCCS Books.

- Romme, M. (2009b). What causes hearing voices? In M. Romme, S. Escher, J. Dillon, D. Corstens, & M. Morris (Eds.), Living with voices: 50 stories of recovery (ch 3, pp. 39–47). PCCS Books.

- Rønnestad, M. H., & Skovholt, T. M. (2003). The journey of the counsellor and therapist: Research findings and perspectives on professional development. Journal of Career Development, 30(1), 5–44. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025173508081

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2002). An overview of self-determination theory. In E. L. Deci & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of self-determination research (ch 1, pp. 3–36). University of Rochester Press.

- Schizophrenia Commission. (2012). The abandoned illness. Rethink Mental Illness. Retrieved June 27, 2016, from https://www.rethink.org/media/514093/TSC_main_report_14_nov.pdf

- Schizophrenia Commission. (2017). Progress report: Five years on. Rethink Mental Illness. Retrieved October 9, 2019 from https://www.rethink.org/media/2586/the-schizophreniacommission-progress-report-five-years-on.pdf

- Seikkula, J., Alakare, B., & Aaltonen, J. (2011). The comprehensive open-dialogue approach in Western Lapland: II. Long-term stability of acute psychosis outcomes in advanced community care. Psychosis, 3(3), 192–204. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17522439.2011.595819

- Sinclair, S., Norris, J. M., McConnell, S. J., Chochinov, H. M., Hack, T. F., Hagen, N. A., McClement, S., & Bouchal, S. R. (2016). Compassion: A scoping review of the healthcare literature. BMC Palliative Care, 15, 1–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-016-0080-0

- Sivec, H. J., & Montesano, V. L. (2012). Cognitive behavioral therapy for psychosis in clinical practice. Psychotherapy, 49(2), 258–270. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028256

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Sage.

- Sweeney, A., Clement, S., Filson, B., & Kennedy, A. (2016). Trauma-informed mental healthcare in the UK: What is it and how can we further its development? Mental Health Review Journal, 21(3), 174–192. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/MHRJ-01-2015-0006

- Verfaille, M. (2011). Mentalizing in arts therapies. Karnac.

- Wadeson, H., & Carpenter, W. T. (1976). A comparative study of art expression of schizophrenic, unipolar depressive, and bipolar manic-depressive patients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 162(5), 334–344. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-197605000-00004

- Watkins, C. E. (2013). The contemporary practice of effective psychoanalytic supervision. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 30(2), 300–328. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030896

- Wood, C. (1997). The history of art therapy and psychosis, 1938–1995. In K. Killick & J. Schaverien (Eds.), Art, psychotherapy and psychosis (ch 8, pp. 144–175). Routledge.

- Wood, C. (2011). The evolution of art therapy in relation to psychosis and poverty. In A. Gilroy (Ed.), Art therapy research in practice (pp. 211–229). Peter Lang.

- Wood, L., Burke, E., & Morrison, A. (2015). Individual cognitive behavioural therapy for psychosis (CBTp): A systematic review of qualitative literature. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 43(3), 285–297. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465813000970

- Wright, T., & Holttum, S. (2020). BAAT guidelines on art therapy for people with a psychosis-related diagnosis. British Association of Art Therapists. https://www.baat.org/Assets/Docs/General/BAAT%20Guidelines%20AT%20Psychosis%20PART%201-2-3.pdf