ABSTRACT

Group-based affective polarisation can emerge around new issues that divide citizens. The public response to vaccines against COVID-19 provided a clear example of a new basis for group divides. Despite scientific consensus regarding the dangers of SARS-CoV-2 as well as the safety and effectiveness of available vaccinations, the public response to the COVID-19 pandemic was strongly politicised during the height of the health crisis. Positive social identities and negative out-group stereotyping developed around support or opposition to the vaccines. Panel survey data from Austria shows that vaccination identities are clearly identifiable and are related to extensive trait-based stereotyping of in- and out-group members. Moreover, we show that vaccination identities are linked to political identities and orientations that pre-date the politicisation of COVID-19 vaccines. Indeed, vaccination identities are more strongly related to political orientations than the decision to get vaccinated itself. Importantly, vaccination identities help us understand downstream attitudes, preferences, and behaviours related to the pandemic, even when controlling for other important predictors such as vaccination status and partisanship for anti-vaccine parties. We discuss the implications and generalizability of our findings beyond the context of the pandemic.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic and the mitigation measures against it – ranging from masking in public spaces to “lockdowns” – generated significant political division. Some of this division can be boiled down to the usual differences between government and opposition (Altiparmakis et al. Citation2021) or between mainstream and populist parties (Falkenbach and Greer Citation2021). However, some measures took on their own political significance, even generating novel social identities (Abrams, Lalot, and Hogg Citation2021). In some countries, mask-wearing emerged as a highly divisive marker of social identity (Faas et al. Citation2021; Powdthavee et al. Citation2021). In other settings, vaccines against COVID-19 generated particularly strong support and opposition, emerging as the flashpoint around which novel identities formed. Emphasising their pride in having been “jabbed”, some people would change their publicly visible social media information to include their vaccination status, while others would take to the streets to protest against vaccination.

In this paper, we explore how vaccination against COVID-19 became politicised (Peretti-Watel et al. Citation2020), emerging as a novel social identity with the potential to fuel broader societal polarisation (Abrams, Lalot, and Hogg Citation2021). We show that vaccination is the kind of salient, divisive issue that can create opinion-based social identities around which affective polarisation emerges (Hobolt, Leeper, and Tilley Citation2021). Theoretically, our study is embedded in long-standing research on group conflict and identities (Tajfel and Turner Citation1979; Brewer Citation1991), especially concerning partisanship (Huddy Citation2001; Greene Citation1999; Citation2004) and affective polarisation (Iyengar, Sood, and Lelkes Citation2012; Hobolt, Leeper, and Tilley Citation2021). In this paper, we apply these frameworks to group identities formed during the COVID-19 pandemic. While such identities were likely based on various aspects, for example past infection or opposition to COVID-19 measures, we focus on vaccination against COVID-19 as a source of group identification.

Our study extends the limited research that directly examines vaccination status as a source of social identity. Pre-pandemic research by Attwell and Smith (Citation2017) and Motta et al. (Citation2021) has been complemented by more recent work focusing on the context of COVID-19 (Bor et al. Citation2023a; Henkel et al. Citation2023). This paper goes beyond this research by investigating the nature of vaccination identities and their attitudinal and behavioural correlates in one comprehensive study. We explicitly measure identities and stereotypes based on group identities stemming from vaccine support and empirically compare the correlates of vaccination identities to those of related concepts such as vaccination status and support for anti-vaccine parties. To do so, we use data from several waves of an online panel survey fielded between May 2020 and May 2022 in Austria (Kittel et al. Citation2020; Citation2021). Most importantly, the panel’s unique structure allows us to make use of attitudes and perceptions predating the vaccine roll-out to gain a better understanding of the formation of vaccination-based group identities.

Overall, we find that vaccination identities are clearly identifiable among the Austrian population and related to extensive stereotyping of in- and out-group members. Vaccination identities are also different from mere vaccination status, which is more neutral and less politically charged. Importantly, vaccination identities are political. For one, pre-vaccination political attitudes predict who will develop such identities, and these are in turn associated with downstream political attitudes, preferences, and behaviours, even when controlling for other important predictors.

Our results imply that it is plausible that vaccination identities had an important role in how the COVID-19 pandemic played out. Moreover, these identities – and related ones – have the potential to become important parts of political conflict in the future. They illustrate how current political debates can create strong intergroup affect that divides the population. In our conclusion, we discuss the implications of our findings for understanding pandemic politics as well as group-based political identities that go beyond partisanship more generally.

Political social identities and affective polarisation during the covid-19 pandemic

Social identities have long been central to our understanding of political conflict. For instance, they are a key component of cleavage politics (Lipset and Rokkan Citation1967). Building on work in social psychology (e.g. Tajfel and Turner Citation1979; Brewer Citation1991), political scientists have studied individuals’ identification with key socio-demographic groups based on, for instance, gender, race or class (e.g. Conover Citation1984; Huddy Citation2001). Importantly, political parties also form the basis of social identities, with partisanship affecting political engagement, political knowledge and vote choice (Campbell et al. Citation1960).

Recently, political scientists have turned to study the out-group derogation that often accompanies in-group affect, most prominently using the term “affective polarization” (Iyengar et al. Citation2019). While this work mostly focuses on partisan groups, Hobolt, Leeper, and Tilley (Citation2021) show that significant political events such as Brexit can also generate group-based affective polarisation (Bliuc et al. Citation2007; Citation2015). Such opinion-based (or issue-based) affective polarisation can cross-cut partisan identities but has similar consequences in terms of intergroup relations, for example in terms of prejudice and discrimination.

Given the intense political conflicts generated by the spread of COVID-19 and the measures to contain its effects (Juen et al. Citation2021; Maher, MacCarron, and Quayle Citation2020), it is unsurprising that the pandemic could have potentially both fostered and been shaped by political identities and intergroup conflict. Existing empirical studies on polarisation during the COVID-19 pandemic have largely focused on partisan support (e.g. Allcott et al. Citation2020; Gadarian, Goodman, and Pepinsky Citation2021, Kerr et al., Citation2021, Rodriguez et al. Citation2022), with only limited research investigating the role of partisan identities specifically (Druckman et al. Citation2021a; Citation2021b; Stoetzer et al. Citation2021).

However, the COVID-19 pandemic may have had implications for social identities beyond partisanship. Taking a broader perspective, Abrams, Lalot, and Hogg (Citation2021) develop a detailed theoretical argument concerning how the COVID pandemic can lay the groundwork for the strengthening of existing social identities as well as the formation of new ones. Initially, extreme crisis situations such as a global pandemic may increase solidarity and bring citizens closer together, blurring the lines between in-group and out-group(s) (Jungkunz Citation2021; Kritzinger et al. Citation2021). However, once the consequences and longevity of the crisis become clearer, this perception of a homogenous in-group fades and group-based differences become salient again (Abrams, Lalot, and Hogg Citation2021). This may concern existing groups – based for instance on gender, age, ethnicity or race – that are already stigmatised in society (Krings et al., Citation2021). However, the crisis may also give rise to new group differences based on vaccination status or containment measures. Moralisation and condemnation in official communication and news coverage, in particular, may play their part (Jaspal and Nerlich Citation2022; Bor et al. Citation2023b). Once group-based differences become salient, a strengthening of in-group identification as well as increased out-group derogation may thus lead to increased affective polarisation between the in- and out-group.

COVID-19 vaccination as a source of group identities

One particular touchstone for political divisions during the COVID-19 pandemic was the decision to get vaccinated. Attwell and Smith (Citation2017) discuss whether the binary decision of whether to get vaccinated or not can be understood through the lenses of social identity theory. They attribute the creation of vaccine-related social identities to the innate human inclination to find solace and inspiration among communities that share similar beliefs. Importantly, they caution that the decision to get vaccinated is significantly swayed by social, moral, and political beliefs. Similarly, Korn et al. (Citation2020) find that the decision to get vaccinated may not be solely perceived as an individual’s personal choice based on their health assessment. Rather, it is often regarded as a moral obligation and part of a social contract, with individuals rewarded for compliance and punished for violation.

Indeed, there is already some evidence that vaccination against COVID-19 led to the formation of opinion-based group identities. In a global conjoint experiment based on 21 countries, Bor et al. (2023) focus on prejudice based on vaccination status (rather than explicit identities). They show that cueing the vaccination status elicits prejudice towards the unvaccinated among the vaccinated, but not vice-versa. While this one-sided prejudice against the unvaccinated is also found by Henkel et al. (Citation2023), they explicitly differentiate vaccination status from its related social identity. They show that the strength of vaccination identity has consequences (going beyond that of vaccination status) on various outcomes such as perceptions of public discourse, perceived everyday discrimination, in-group preferences, and reactance toward vaccination mandates. Here, vaccination identity is a driver of political polarisation on pandemic-related perceptions and preferences. Finally, Bor et al. (Citation2023b) and Graso et al. (Citation2023) examine the moralisation and moral condemnation of vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic and how these led to social division.

While these previous studies provide first insights into the nature and consequences of vaccination identities during the COVID-19 pandemic, none of the studies explore who was more likely to develop a vaccination identity. Moreover, they do not consistently compare vaccination identity to related partisan identities (e.g. preferences for COVID-sceptic or anti-vaccine parties) and vaccination status itself.

Expectations

We have several expectations concerning the nature of vaccination identities in Austria, where there was a high degree of politicisation of COVID-19 vaccination. We expect that large proportions of the population formed a strong in-group identification based on their shared opinion about the COVID-19 vaccination and that these identities are linked to extensive in- and out-group stereotyping. We also expect these identities to only partially overlap with vaccination status and partisanship.

Furthermore, we expect vaccination identities to be political, more so than the decision to get vaccinated (Attwell and Smith Citation2017). Group identification is thus qualitatively different from group membership (Conover Citation1984). We expect that vaccination-based group identities build on objective group membership, but also on how individuals related to political parties, institutions and the media prior to the pandemic. Identities should thus be strongly correlated with political attitudes and perceptions, more so than with virus-related threat perceptions or related sociodemographic factors.

Finally, political identities provide a lens to interpret political events and decisions, drive the downstream development of political preferences and provide a strong impetus for political action (Campbell et al., Citation1960; Conover Citation1984). Moreover, out-group stereotyping will be associated with a greater willingness to accept measures and restrictions aimed primarily at out-group members, while the opposite should be the case when it comes to measures and restrictions that mainly target in-group members (Iyengar et al. Citation2019). Hence, we anticipate that the strength of vaccination identities should correlate strongly with downstream political preferences, particularly regarding virus mitigation measures.

Case

Previous research on affective polarisation in general (e.g. Iyengar et al. Citation2019; Hobolt, Leeper, and Tilley Citation2021) and during COVID-19 more specifically (e.g. Druckman et al. Citation2021a) has often focused on two-party systems such as the US or the UK. Our data is from Austria, a good example of a European multi-party democracy and of the evolution of public sentiment during COVID-19. As in many European countries, a strong “rally-round-the-flag” effect at the beginning of the pandemic (Kritzinger et al. Citation2021) was followed by a period where COVID-19 measures were strongly politicised by at least one major populist challenger. This politicisation also tapped into COVID-19-related conspiracy theories and anti-vaccine sentiment (Eberl, Huber, and Greussing Citation2021; Paul, Eberl, and Partheymüller Citation2021; Stamm et al. Citation2022).

During the study period (between May 2020 and May 2022), Austria ranked among the countries in Western Europe with the lowest COVID-19 vaccination uptake. It was also the first European country that legislated for a general vaccine mandate for COVID-19. Announced in November 2021, the vaccine mandate was active from February to July 2022. Two Austrian parties positioned themselves strongly against government mitigation measures and vaccination efforts, namely the populist radical right Freedom Party (FPÖ) and an ephemeral regional party, People – Freedom – Fundamental Rights (MFG). Yet, vaccine scepticism and opposition to the general vaccine mandate were not driven by partisanship alone (Paul, Eberl, and Partheymüller Citation2021; Stamm et al. Citation2022). While political mobilisation around COVID-19 vaccination was high, Bor, Jørgensen, and Petersen (Citation2023a) show that Austria still only had rather moderate levels of antipathy towards the unvaccinated among the 21 countries examined.

Data and methods

We use data from the Austrian Corona Panel Study (ACPP), available via the Austrian Social Science Data Archive (AUSSDA). Respondents from an online access panel (certified under ISO 20252) were selected based on age, gender, gender x age, region (province), educational level, and municipality size. Around 1,500 respondents were interviewed at regular intervals from March 2020 onwards, with fresh respondents recruited in each wave to compensate for drop-outs (Kittel et al. Citation2020; Citation2021).

We mainly focus on respondents who took part in Wave 28 of the study, but add information from respondents from earlier waves, mostly Wave 6, to assess the correlates of vaccine-related group-based identities. Wave 6 was fielded at the start of the pandemic in May 2020, still long before the first vaccines would be within reach, while Wave 28 was fielded between 14 and 21 January 2022, just a few weeks after a general vaccine mandate was announced in Austria. We present additional results from Wave 32, which was fielded between 20 and 29 May 2022, so a bit over four months later. All question wordings are presented in the supplemental material.

In Waves 28 and 32 of the panel survey, we asked two sets of questions relating to vaccination-based identities. In all questions, we referred to identification with and perceptions of groups – either pro- or anti-vaccination supporters – in order to highlight that we were asking about attitudes relating not to vaccines but rather to social groups.

Our first set of questions asked respondents whether they saw themselves as part of the group of vaccination supporters, part of the group of vaccination opponents, or neither. Those answering “neither” were then asked whether they felt closer to one of the two groups, again with “neither” as a third option. After that, those who said that they felt they were part of or close to one of the groups were also asked how close they felt to the group they chose: “very close”, “somewhat close” or “not very close”. These questions are based directly on standard batteries that measure partisan identification (Druckman and Levendusky Citation2019). While important alternative measures of political identities have been proposed (e.g. Huddy, Mason, and Aarøe Citation2015), limitations of survey space meant that only this measure of identity was included in the panel survey.

Our second set of questions on affective polarisation is related to prejudice against and stereotyping of members of the out-group. We asked about the perceived traits of vaccination supporters and vaccination opponents, specifically the extent to which each of four characteristics – “intelligent”, “honest”, “selfish”, and “unpatriotic” – applies to each group (Hobolt, Leeper, and Tilley Citation2021; Iyengar, Sood, and Lelkes Citation2012). Hobolt, Leeper, and Tilley (Citation2021) also asked three other traits (“open-minded”, “closed-minded” and “hypocritical”) that we dropped as they were hard to translate using single words. In the realm of classic social psychological models of social perception, the traits “intelligent” and “honest” can be most effectively associated with “high competence/high warmth” (Fiske, Cuddy, and Glick Citation2007), or alternatively, “good-intellectual” and “good social” (Rosenberg, Nelson, and Vivekananthan Citation1968). Conversely, the trait “selfish” aligns more closely with “medium competence/low warmth” (Fiske, Cuddy, and Glick Citation2007) or “bad-social” (Rosenberg, Nelson, and Vivekananthan Citation1968). Additionally, we use the trait “unpatriotic,” which, although not explicitly covered in classic social psychological models, is likely to exhibit similarities with “selfish” and was included in a study of partisan groups (Iyengar, Sood, and Lelkes Citation2012). Patriotism gained particular significance in the context of COVID-19, given the profound politicisation of the pandemic measures by radical right and nativist parties.

Nature, strength and stability of covid-19 vaccination identities

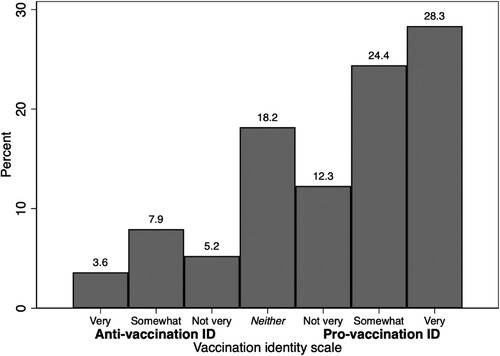

We first examine whether there was strong in-group identification on the basis of vaccination status. shows that vaccination-based group identities are indeed widespread. Only 18% of respondents do not identify as being part of one of the two groups (pro-vaccination or anti-vaccination). Taking both groups together, in-group attachment is strong. In the 2017 election survey (Aichholzer et al. Citation2018), the equivalent partisan identification question had 30% of respondents who did not identify with a party, with only 18% very close and 47% somewhat close to their in-party. In other words, the attachment to vaccination groups is larger and stronger than the attachment to partisan groups.Footnote1

Figure 1. Distribution and strength of vaccination identities, Austria, January 2022.

Note. Data from Wave 28, ACPP. n = 1,524.

Looking separately at the two groups, 65% of respondents identify as being part of the pro-vaccination group. In turn, 17% of respondents identify as part of the anti-vaccination group. Comparing the strength of attachment, it is interesting that attachment to vaccination groups is stronger for those with a pro-vaccination identity than for those with an anti-vaccination identity (npro = 991, nanti = 256, χ2 = 45, p < 0.001).

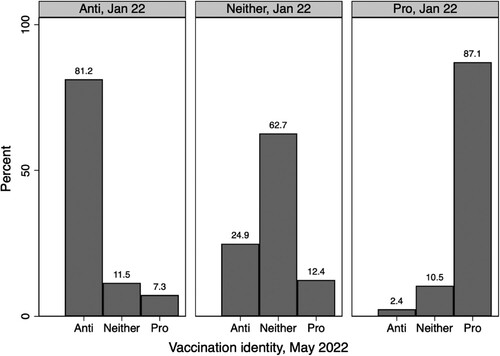

Vaccination identities were also largely stable over a longer period. Comparing January and May 2022, shows that 87% maintained their pro-vaccination identity, while 81% stuck with their anti-vaccination identity. There is very limited movement towards the opposing identity. Interestingly, almost 40% of those without a vaccination identity in January 2022 had adopted such an identity by May 2022. Moreover, the strength of vaccination identities (on a 0–2 categorical scale) did not strongly decline, despite a general reduction in the salience of vaccination as a topic of public debate. Indeed, the strength of anti-vaccination identities even increased slightly (Pro-vaccination group: meanJAN = 1.25, meanMAY = 1.18, nJAN = 991, nMAY = 667, t = 1.86, p = 0.06; anti-vaccination group: meanJAN = 0.90, meanMAY = 1.08, nJAN = 256, nMAY = 170, t = 2.46, p = 0.01).

Figure 2. Stability of vaccination identities, Austria, January and May 2022.

Notes. Data from Waves 28 and 32, ACPP. Data not weighted.

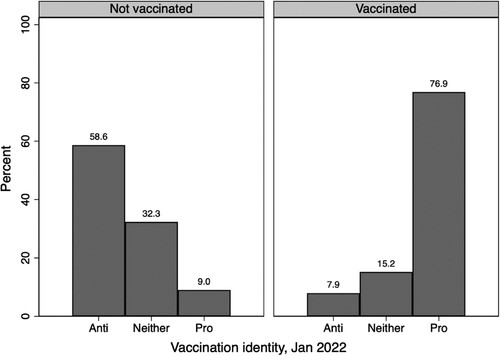

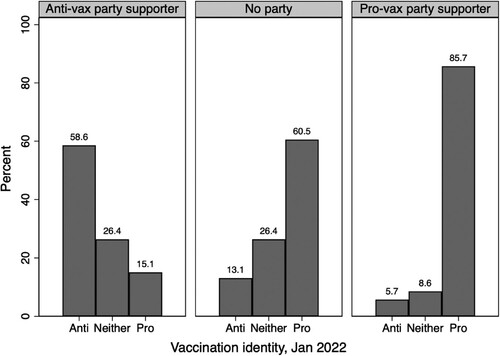

Vaccination identities also differ from vaccination status and partisanship for anti-vaccine parties (see and ). Vaccination status is measured simply as whether someone has received at least one vaccine dose against COVID-19. Party support for anti-vaccination parties is measured as those who say they would vote for the radical-right Freedom Party or the anti-vaccine party MFG party.

Figure 3. Distribution of vaccination identities by vaccination status, Austria, January 2022.

Notes. Data from Wave 28, ACPP. n = 1,524. Vaccination status and identity: χ2 = 527, p < 0.001.

Figure 4. Distribution of vaccination identities by party support, Austria, January 2022.

Notes. Data from Wave 28, ACPP. n = 1,505 (party support); no party includes respondents who answer don’t know, do not want to say, blank/invalid voters; anti-vaccine party: FPÖ, MFG, pro-vaccine party: all others; party support and vaccination identity: χ2 = 508, p < 0.001.

77% of people who have received a vaccine report such an identity. Conversely, 59% of the unvaccinated have an anti-vaccination identity, so the proportion with that vaccination status group who also have this identity is lower; part of the reason for this may lie in the lower social desirability of an anti-vaccination identity. Unsurprisingly, only 8% of the vaccinated have an anti-vaccination identity. Interestingly, these 8% are nevertheless 39% of those with an anti-vaccination identity, so two-fifths of those with an anti-vaccination identity have received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. The overlap between objective group membership and subjective group identification is thus strong, but by no means perfect.

Similarly, vaccination identities correlate with party support. Only 59% of those who say they would vote for one of the parties that currently have an anti-vaccination stance also have an anti-vaccination identity, though 86% of those who would vote for a party with a pro-vaccination stance also have a pro-vaccination identity. Overall, it is important to acknowledge that vaccination-based identities are related to vaccination status and partisan support, but by no means coterminous with these.

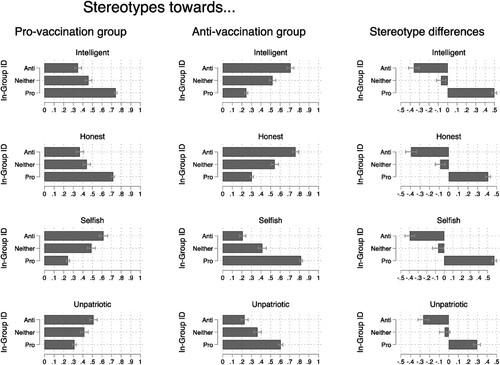

The second component of vaccination-based group identities and conflict is that vaccination identities foster sentiments of in-group favourability and out-group denigration. We also see this in our data (), where each group holds clear stereotypes about their own group as well as the out-group. Those who identify as part of the pro-vaccination group see the anti-vaccination group as less intelligent and honest and more selfish and unpatriotic, and vice versa. The weakest differences are visible for the characteristic “unpatriotic”. Figure A1 in the Online Appendix shows the same results by vaccination status rather than vaccination group identity. It is important to note that these stereotypes are likely to be strongly related to other, pre-existing sets of stereotypes about important political and social groups. For instance, the stereotypes held towards anti-vaccination group identifiers may be similar to those held towards supporters of anti-vaccination parties.

Figure 5. Stereotypes of vaccine-based in- and out-groups, Austria, January 2022.

Notes. Data from Wave 28, ACPP. Mean scores across Group ID and stereotypes are shown, along with 95% confidence intervals. Weights used. Scale: 0 = “does not apply at all”, 1 = “applies completely”.

Overall, the third column shows that out-group stereotyping is stronger among those with a pro-vaccination identity. For instance, the gap in the mean assessment of the intelligence of the two groups is + .5 units among those with a pro-vaccination identity, but only – .35 among those with an anti-vaccination identity. Importantly, those without a vaccination identity do not hold strong stereotypes in either direction. Consistent patterns persist across all four characteristics. For a more comprehensive analysis, we utilised regression models that control for partisanship, vaccination status, left-right ideology, and sociodemographic variables. The results, including statistical significance tests, can be found in Table A1 of the Online Appendix.

The greater gap in stereotypes among the pro-vaccination group exists due to their more negative out-group assessments. While the two groups are similarly positive about their in-group, the pro-vaccination group’s evaluations of the characteristics of the anti-vaccination group are somewhat more negative.

Long-term correlates developing a vaccination identity

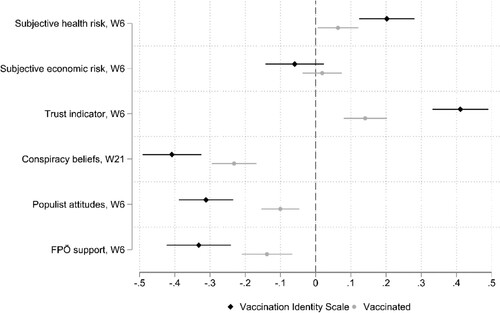

Next, we turn to the factors that are associated with having a vaccination identity. Our focus is on comparing the factors associated with having a relevant vaccination identity and how these differ from simply being vaccinated or not. While there is significant research on the question of why individuals decide to get vaccinated against COVID-19 (e.g. Paul, Eberl, and Partheymüller Citation2021; Troiano and Nardi Citation2021), our interest here is in uncovering what distinct factors are linked to who develops vaccine-related identities. We carry out this comparison by taking advantage of the long-term panel component of our data. We run two linear regression models, predicting either vaccination identity or vaccination status. Vaccination identities are standardised to have a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 0.5, with positive values signifying a more pro-vaccination identity. Vaccination status is again measured simply as whether someone has received at least one vaccine dose against COVID-19. A value of 1 means that respondents are vaccinated.

Our key correlates of vaccination identities are taken from early on in the pandemic, taking advantage of our long-term panel. Specifically, we mostly use measures from Wave 6 (May 2020) and examine how the outcome variables are related to various predictors. The predictors are (1) reactions to the early stages of the pandemic, especially health and economic risks, (2) trust in institutions (e.g. government, public broadcaster, and science), (3) political ideology, (4) partisanship, (5) conspiracy beliefs and (6) populist attitudes. We expect concern with the health risks of the pandemic to be associated with pro-vaccination identities, and concern with the economic risks of the pandemic to be associated with anti-vaccination identities. High levels of trust in institutions should be associated with pro- rather than anti-vaccination identities, while anti-vaccination identities should be more prevalent among the ideological extremes. Those who believe in conspiracies and hold populist attitudes should be more likely to have anti-vaccination identities, as should those who support the radical right.

The subjective health and economic risk perceptions created by COVID-19 are measured on a 5-point scale from “very low” to “very high”. Trust in a set of seven institutions (e.g. government, public broadcaster, and science) is measured on a scale from 0 (“no trust at all”) to 10 (complete trust). We also include a measure of conspiracy beliefs that are not directly related to COVID-19, based on support on a 1–5 scale for two statements, as well as a measure of populist attitudes, based on support on a 5-point scale for six statements (see supplemental material for item wordings), and support for the radical-right Freedom Party of Austria in wave 6, also measured on a 0–10 scale. Lastly, we control for individuals’ left-right self-placement on a scale from 0 (“left”) to 10 (“right”) (Ruisch et al. Citation2021), as well as left-right ideology as a quadratic term as extremes on both sides may be opposed to vaccines, and add a set of sociodemographic controls. The Cronbach’s alpha for the trust scale, the conspiracy beliefs, and the populism scale are 0.92, 0.77, and 0.82, respectively. All continuous predictors are standardised to have a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 0.5.

presents the coefficients from separate models based on the individual focal variables – in addition to a set of controls, such as ideology, ideological extremism, gender, age, education, whether the respondent lives in Vienna, and migration background – predicting vaccination identities and vaccination status (see Table A2 Models 1a-f and 2a-f).Footnote2

Figure 6. Predicting vaccination ID and vaccination status.

Notes. Full models in Table A2 in the Online Appendix. Vaccination identity scale standardised to have a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 0.5, where higher values mean that respondents have a stronger pro-vaccination identity. Vaccination status is 1 if the respondent has received at least one vaccine dose against COVID-19, 0 otherwise.

Our results show, first, that subjective health perceptions at the start of the pandemic are strongly associated with the subsequent tendency to develop a pro-vaccination identity and to a much weaker extent with vaccination status. Perceived economic risks of the pandemic do not show a similar association with either outcome variable.

Next, several politically relevant variables are strongly associated with developing a vaccination identity. Higher institutional trust, measured long before vaccine rollout, is associated with pro-vaccination identities (and with the probability of being vaccinated). Conspiracy beliefs in March 2021 and FPÖ party support at the start of the pandemic are both robustly negatively associated with pro-vaccination identities and being vaccinated. While populist attitudes show a clear negative association with both outcomes in the models shown in , no clear association with either outcome variable is left in the full model including all focal variables at once (see Table A2). However, our robustness test that excludes conspiracy beliefs – measured only in a later wave – from the full model again shows an association between populist attitudes and vaccination identities (see Online Appendix Figure A2 and Table A3), which suggests that populist attitudes and conspiracy beliefs are strongly related (e.g. Eberl, Huber, and Greussing Citation2021; Huber, Greussing, and Eberl Citation2022). Results only excluding FPÖ party support in Wave 6 as a predictor show very similar patterns overall (see Online Appendix Figure A3 and Table A3).

COVID-19 vaccination identities and support for pandemic mitigation measures

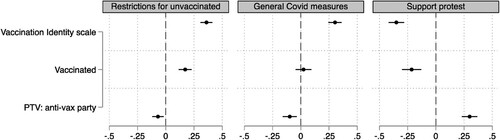

Finally, we examine how vaccination identities relate to various pandemic-related political attitudes, preferences, and behaviours. We begin with three outcome variables. First, we examine support for measures targeting unvaccinated citizens in particular – specifically, entry restrictions to restaurants and events. Both were measured on a 4-point scale from “restriction should currently definitely not be in place” to “restriction should currently definitely be in place”. Second, we examine the correlation between identities and general attitudes towards tough measures to restrict the spread of COVID-19. We built an additive index based on approval to the following four items of the survey: “We should take the toughest possible restrictions to shorten the crisis’; “We should only relax measures when new infections are at zero”; “We should lift all restrictions, instead focus on personal responsibility”; and “Measures should be relaxed even if this leads to more people getting infected”. Third, we examine support for COVID-related protests against government measures using approval of the statement “I support demonstrations against the COVID measures’. All of these measures are standardised to have a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 0.5.

We predict these attitudes using the same vaccination identity scale used above. Our models control for socio-demographic attributes and for whether someone has had COVID-19, egotropic as well as sociotropic health and economic risk perceptions. The most important – and most methodologically difficult – controls are for whether someone is vaccinated and for whether someone supports a party that has positioned itself against vaccination (i.e. the Freedom Party or the anti-vaccine party MFG). These two controls are strong, and their relationship to identity will likely be as both a cause and consequence. We cannot make strong causal claims for our analysis. To partly address this, we show results without the control for vaccination status and anti-vaccination party support in Tables A8 and A9 of the Online Appendix; these unsurprisingly show that the effects of vaccination identities are even stronger.

For these analyses, both vaccination identities and anti-vaccination party support are rescaled to have a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 0.5, to make their effects comparable to those of vaccination status (following the recommendations of Gelman Citation2008). Full results of the regression models are in Table A4 and A5 in the Online Appendix.

shows that vaccination identities help to account for pandemic-related attitudes and preferences. Moreover, the association is large: a two-standard-deviation change in the identity scale is associated with a change of .25 to .5 points, which amounts to between half and a full standard deviation for all variables. Hence, vaccination identities are strongly correlated with citizens’ attitudes and preferences relating to the pandemic, even when controlling for vaccination status and anti-vaccination party support. Indeed, vaccination identities are generally more strongly associated with attitudes and preferences than vaccination status or support for anti-vaccine parties.

Figure 7. Association of vaccination identity, vaccination status and support for anti-vaccine parties with a set of pandemic-related attitudes and preferences.

Notes. For variable descriptions, see text. Full models in Table A4 in the Online Appendix.

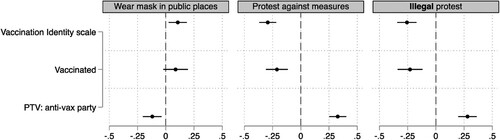

Turning to pandemic-related behaviour, we also use three outcome variables. First, we examine the willingness to wear a mask in public places. The item was measured on a 5-point scale from “close to never” to “close to always”. Second, we examine the general willingness to take part in COVID-related protests against government measures. Finally, we consider the willingness to take part even in illegal protests. Again, these measures are standardised to have a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 0.5.

shows that vaccination identities are associated with some pandemic-related behaviours, even when controlling for vaccination status, support for anti-vaccine parties, ideology, and socio-demographic factors. Vaccination identities predict the willingness to protest against COVID-19 protective measures, to support anti-vaccine parties, and to wear a mask in public spaces.Footnote3 Support for anti-vaccine parties is again strongly associated with behaviour, which is perhaps related to these parties’ mobilising potential. Overall, vaccination identities are linked to citizens’ pandemic-related behaviours to a similar extent as vaccination status and support for anti-vaccine parties, and exists even when these factors are controlled for.

Figure 8. Coefficients for vaccination identity, vaccination status and support for anti-vaccine parties in models predicts pandemic-related behaviours.

Notes. For variable descriptions, see text. Full models in Table A5 in the Online Appendix.

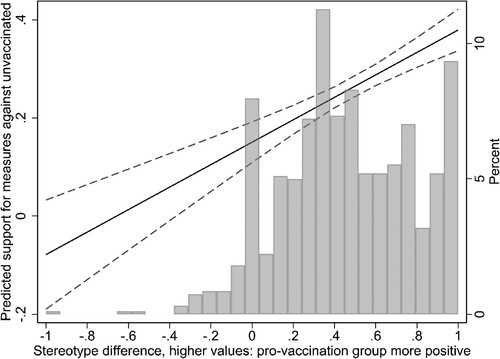

Finally, depicts the association of stereotyping with support for measures aimed specifically at the unvaccinated population (i.e. exclusion from restaurants and public events). This analysis only considers those with a pro-vaccination identity.Footnote4 This Figure shows that greater differences between positive stereotypes about the pro-vaccination group and negative stereotypes about the anti-vaccination group are associated with support for measures that restrict the freedom of the unvaccinated.Footnote5 For those among the pro-vaccination group that engage in very strong stereotyping (difference of 1), the support for these measures is about .25 units (or half a standard deviation) higher than among those who refrain from stereotyping the out-group (difference of 0). Hence, even beyond simple group identification, the extent to which people stereotype each other is associated with a greater willingness to exclude and treat differently those among the out-group.

Conclusion and discussion

Our analysis shows that four-fifths of the Austrian population developed identities based on their stance toward vaccination. These identities are stronger for the pro-vaccination group, only partially overlap with actual vaccination status, and are more prominent than partisan identities. Moreover, in- and out-group stereotyping is extensive.

These results speak to recent research highlighting the existence of vaccine-related social identities (Motta et al. Citation2021), the willingness to discriminate based on vaccination status (Bor, Jørgensen, and Petersen Citation2023a; Henkel et al. Citation2023) as well as the potential for opinion-based political identities more generally (Hobolt, Leeper, and Tilley Citation2021). In addition, we show that political orientations from early stages of the pandemic predict who developed vaccination-based identities: they are related to pre-vaccination levels of institutional trust (i.e. government, science, and the media) and connected to COVID-independent conspiracy beliefs and populist radical right party support. This relationship concerning institutional trust aligns among others with prior research discussing the influence of official communication on the moralisation and moral condemnation of preventive behaviour during the pandemic (Bor et al. Citation2023b; Graso et al. Citation2023). Finally, vaccination-based identities are associated with downstream political attitudes, preferences, and behaviours related to the pandemic. This association is present even when controlling for vaccination status and support for anti-vaccine parties.

Vaccination as a source of identification during COVID-19 was appropriate in the context we study, Austria, where much of the public debate in the latter stages of the pandemic concerned this health measure, including the (never fully implemented) vaccine mandate. In other contexts, social identities may have been generated by other factors, for instance mask-wearing, in ways that parallel the findings for vaccination that we present here. In addition, we note that pre-pandemic attitudes and identities – such as political ideology or partisanship – are important to understanding the pandemic-related identities that emerged. However, our study does not shed light on how vaccination identities are related to other pandemic-related social identities, and further research needs to explore the complex relationships between different politicised identities.

This study naturally has methodological limitations. While the panel survey design allowed us to investigate possible predispositions for the development of vaccination identities, we lacked pre-pandemic measures (opting instead for pre-vaccine measures). Moreover, our analysis of the downstream implications of identities is inherently limited as we have to use cross-sectional data for these analyses; for instance, while support for anti-vaccine parties, anti-vaccination identities and related political behaviour are correlated, the exact chains of causality are impossible to establish with our data. Moreover, additional, more detailed measures of identity that, for instance, capture expressive aspects (Huddy, Mason, and Aarøe Citation2015) would have been useful.

Linked to these limitations, there are three natural extensions to the research presented in this paper. First, will vaccination-based identities fade away as the pandemic that triggered the social identities will become less salient? Or will the identities persist, perhaps adapt and transform to fit other political conflicts that go beyond the pandemic context? Second, how did vaccination identities vary across countries? Understanding these patterns could point us to ways of limiting the emergence of new divisive identities during other current or future crises, such as the climate crisis. Third, what are the consequences of these identities? Do they function as a social identity, determining responses to unrelated questions (Malka and Lelkes Citation2010)? Do they shape how new conflicts are incorporated into political debates?

The implications of our findings deserve to be discussed carefully. One notable result of our study is that there are high levels of in-group identification and out-group stereotyping within both the pro-vaccination group as well as the anti-vaccination group. Moreover, those pro-vaccination identifiers with strong out-group stereotypes are particularly likely to support policy measures imposing restrictions targeting the (unvaccinated) out-group. This study echoes a US-based study, showing that vaccinated individuals are more inclined to discriminate against and impose restrictions on the rights of the unvaccinated (Bor, Jørgensen, and Petersen Citation2023a).

Remedies to vaccination-related affective polarisation, while important, may conflict with reasonable public health goals during a pandemic. For instance, recent research suggests that a decrease in vaccination-related affective polarisation could be achieved by de-emphasising vaccination while emphasising other identities (Abrams, Lalot, and Hogg Citation2021; Vignoles et al. Citation2021; Henkel et al. Citation2023). While reducing the emphasis on vaccination in official communication may not always be a viable option during acute crises, previous research suggests that emphasising communal reasoning and community spirit in vaccination campaigns not only has some potential to slightly increase vaccine uptake (Stamm et al. Citation2023) but also, to some extent, mitigate the development of strong identities centred around vaccination (Attwell and Smith Citation2017). Actual experimental tests of such identity-based interventions in the context of COVID-19 vaccination identities remain scarce and inconclusive (e.g. Sprengholz, Betsch, and Böhm Citation2024).

More generally, opinion-based social identities are not the same as cleavage-based social identities (e.g. based on race or religion). Prejudice and discrimination based on such social identities cannot be equated. There is a difference between negative stereotypes based on gender or skin colour and those based on voluntarily chosen associations such as partisanship or vaccination (Wagner, Citation2024). Moreover, vaccination identities were formed during the pandemic and correlate with preventive behaviours as well as pandemic preferences. For those wishing to protect their own health as well as that of others, avoiding those with an anti-vaccination identity is thus a morally more justifiable heuristic than, say, avoiding socio-demographic groups with higher (perceived) COVID-19 prevalence rates. As contemporary developments, such as the climate crisis or the Russian invasion of Ukraine, increasingly become politicised, related opinion-based social identities that are directly tied to real-world behaviours and clear policy preferences may emerge as well. Hence, it will remain essential to maintain awareness of this fundamental distinction between cleavage-based and opinion-based identities. Doing so will foster a nuanced understanding of resulting social dynamics, their possible consequences, and viable interventions.

Finally, while not all issue-based disagreements may lend themselves to the formation of social identities, we could show that group conflict is not restricted to long-standing social identities. Importantly, vaccination-based identities – while correlated with vaccination status – are inherently political, but not a mere proxy for anti-vaccine partisanship. Future work should provide a more general framework for analysing opinion-based affective polarisation and develop an understanding of the types of social divides that lead to the emergence of such identities.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (417.5 KB)Acknowledgements

The data collection of the Austrian Corona Panel Project (ACPP) was made possible by COVID-19 Rapid Response Grant EI-COV20-006 of the Wiener Wissenschafts- und Technologiefonds (WWTF), financial support by the rectorate of the University of Vienna, and funding by the FWF Austrian Science Fund (P33907; Elise Richter Grant AV561). Further funding by the Austrian Social Survey (SSÖ), the Vienna Chamber of Labour and the Federation of Austrian Industries is gratefully acknowledged. Markus Wagner’s work on this article was supported by the European Research Council (PARTISAN, project number: 101044069).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The significance test for a difference in the proportion of respondents with a partisan or vaccination identity is χ2 = 53, p<0.001 (nACPP = 1,524, nAUTNES = 1,203). For the strength of identification among those with an identity, the equivalent statistical significance test is χ2 = 121, p<0.001 (nACPP = 1,247, nAUTNES = 858).

2 Full models including all focal variables are presented in Table A2 Model 1 and Model 2. As conspiracy beliefs were only measured in Wave 21, in March 2021, we present robustness tests that exclude this variable in Figure A2 and Table A3, Models 1a and 2a. Moreover, since party support is likely partly post-treatment to other political attitudes, we show results without this control in Figure A3 and Table A3, Model 1b and 2b. All in the Online Appendix.

3 In Tables A6 and A7 in the Online Appendix we control for anti-vaccination party identification instead of the (continuous) measure of support for anti-vaccination parties. As a proxy for party identification, we code all those who say they are certain they would vote for one of the two anti-vaccination parties (10 out of the 10 on the probability scale). The results show that the anti-vaccination identities are in most instances equal or stronger in their association with outcomes than anti-vaccination party identities.

4 We do not have a comparable measure for those with an anti-vaccination identity as there were no measures only targeting the vaccinated population.

5 This analysis controls for the strength of the pro-vaccination identities. Results do not differ if we exclude this control. The effect of stereotype differences is larger for those with weak pro-vaccination identities. See Table A10 in the Online Appendix.

References

- Abrams, D., F. Lalot, and M. A. Hogg. 2021. “Intergroup and Intragroup Dimensions of COVID-19: A Social Identity Perspective on Social Fragmentation and Unity.” Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 24 (2): 201–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430220983440.

- Aichholzer, Julian, Sylvia Kritzinger, Markus Wagner, Nicolai Berk, Hajo Boomgaarden, and Wolfgang C. Müller. 2018. “AUTNES Comparative Study of Electoral Systems Post-Election Survey 2017 (CSES Edition)”, AUSSDA,V4,UNF:6:XZ6B7FsjGdiGzmuYYM + kkA == [fileUNF], https://doi.org/10.11587/W193UZ.

- Allcott, H., L. Boxell, J. Conway, M. Gentzkow, M. Thaler, and D. Yang. 2020. “Polarization and Public Health: Partisan Differences in Social Distancing During the Coronavirus Pandemic.” Journal of Public Economics 191: 104254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104254.

- Altiparmakis, A., A. Bojar, S. Brouard, M. Foucault, H. Kriesi, and R. Nadeau. 2021. “Pandemic Politics: Policy Evaluations of Government Responses to COVID-19.” West European Politics 44 (5-6): 1159–1179. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2021.1930754.

- Attwell, K., and D. T. Smith. 2017. “Parenting as Politics: Social Identity Theory and Vaccine Hesitant Communities.” International Journal of Health Governance 22 (3): 183–198. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJHG-03-2017-0008.

- Bliuc, A. M., C. McGarty, K. Reynolds, and D. Muntele. 2007. “Opinion-Based Group Membership as a Predictor of Commitment to Political Action.” European Journal of Social Psychology 37 (1): 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.334.

- Bliuc, A. M., C. McGarty, E. F. Thomas, G. Lala, M. Berndsen, and R. Misajon. 2015. “Public Division About Climate Change Rooted in Conflicting Socio-Political Identities.” Nature Climate Change 5: 226–229. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2507.

- Bor, A., F. Jørgensen, M. F. Lindholt, and M. B. Petersen. 2023b. “Moralizing the COVID-19 Pandemic: Self-Interest Predicts Moral Condemnation of Other's Compliance, Distancing, and Vaccination.” Political Psychology 44 (2): 257–279. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12835.

- Bor, A., F. Jørgensen, and M. B. Petersen. 2023a. “Discriminatory Attitudes Against Unvaccinated People During the Pandemic.” Nature 613 (7945): 704–711. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05607-y.

- Brewer, M. B. 1991. “The Social Self: On Being the Same and Different at the Same Time.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 17 (5): 475–482. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167291175001.

- Campbell, A., P. Converse, W. Miller, and D. E. Stokes. 1960. The American Voter. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

- Conover, P. J. 1984. “The Influence of Group Identifications on Political Perception and Evaluation.” The Journal of Politics 46 (3): 760–785. https://doi.org/10.2307/2130855.

- Druckman, J. N., S. Klar, Y. Krupnikov, M. Levendusky, and J. B. Ryan. 2021a. “How Affective Polarization Shapes Americans’ Political Beliefs: A Study of Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Journal of Experimental Political Science 8 (3): 223–234. https://doi.org/10.1017/XPS.2020.28.

- Druckman, J. N., S. Klar, Y. Krupnikov, M. Levendusky, and J. B. Ryan. 2021b. “Affective Polarization, Local Contexts and Public Opinion in America.” Nature Human Behaviour 5 (1): 28–38. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-01012-5.

- Druckman, J. N., and M. S. Levendusky. 2019. “What do we Measure When we Measure Affective Polarization?” Public Opinion Quarterly 83 (1): 114–122. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfz003.

- Eberl, J.-M., R. A. Huber, and E. Greussing. 2021. “From Populism to the “Plandemic”: Why Populists Believe in COVID-19 Conspiracies.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 31 (sup1): 272–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457289.2021.1924730.

- Faas, T., D. Schieferdecker, P. Joly, T. Bibu, and D. Klinke. 2021. „Pandemie und Polarisierung: (Wechselseitige) Wahrnehmungen von Befürworter*innen und Gegner*innen der Corona-Maßnahmen“. Policy Brief 3/2021, available at: https://www.polsoz.fu-berlin.de/polwiss/forschung/systeme/empsoz/forschung/rapid-covid/news/rapidcovid_policybrief3.html.

- Falkenbach, M., and S. L. Greer. 2021. “Denial and Distraction: How the Populist Radical Right Responds to COVID-19; Comment on “a Scoping Review of PRR Parties’ Influence on Welfare Policy and its Implication for Population Health in Europe”.” International Journal of Health Policy and Management 10 (9): 578–580.

- Fiske, S. T., A. J. Cuddy, and P. Glick. 2007. “Universal Dimensions of Social Cognition: Warmth and Competence.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 11 (2): 77–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2006.11.005.

- Gadarian, S. K., S. W. Goodman, and T. B. Pepinsky. 2021. “Partisanship, Health Behavior, and Policy Attitudes in the Early Stages of the COVID-19 Pandemic.” PLoS One 16(4).

- Gelman, A. 2008. “Scaling Regression Inputs by Dividing by two Standard Deviations.” Statistics in Medicine 27 (15): 2865–2873. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.3107.

- Graso, M., K. Aquino, F. X. Chen, and K. Bardosh. 2023. “Blaming the Unvaccinated During the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Roles of Political Ideology and Risk Perceptions in the USA.” Journal of Medical Ethics.

- Greene, S. 1999. “Understanding Party Identification: A Social Identity Approach.” Political Psychology 20 (2): 393–403. https://doi.org/10.1111/0162-895X.00150.

- Greene, S. 2004. “Social identity theory and party identification.” Social Science Quarterly 85 (1): 136–153. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0038-4941.2004.08501010.x.

- Henkel, L., P. Sprengholz, L. Korn, C. Betsch, and R. Böhm. 2023. “The association between vaccination status identification and societal polarization.” Nature Human Behaviour 7 (2): 231–239. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-022-01469-6.

- Hobolt, S. B., T. J. Leeper, and J. Tilley. 2021. “Divided by the Vote: Affective Polarization in the Wake of the Brexit Referendum.” British Journal of Political Science 51 (4): 1476–1493. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123420000125.

- Huber, R. A., E. Greussing, and J.-M. Eberl. 2022. “From Populism to Climate Scepticism: The Role of Institutional Trust and Attitudes Towards Science.” Environmental Politics 31(7): 1115–1138. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2021.1978200.

- Huddy, L. 2001. “From Social to Political Identity: A Critical Examination of Social Identity Theory.” Political Psychology 22 (1): 127–156. https://doi.org/10.1111/0162-895X.00230.

- Huddy, L., L. Mason, and L. Aarøe. 2015. “Expressive Partisanship: Campaign Involvement, Political Emotion, and Partisan Identity.” American Political Science Review 109 (1): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055414000604.

- Iyengar, S., Y. Lelkes, M. Levendusky, N. Malhotra, and S. J. Westwood. 2019. “The Origins and Consequences of Affective Polarization in the United States.” Annual Review of Political Science 22: 129–146. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-051117-073034.

- Iyengar, S., G. Sood, and Y. Lelkes. 2012. “Affect, not ideology: A social identity perspective on polarization.” Public Opinion Quarterly 76 (3): 405–431. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfs038.

- Jaspal, R., and B. Nerlich. 2022. “Social Representations of COVID-19 Skeptics: Denigration, Demonization, and Disenfranchisement.” Politics, Groups, and Identities, 1–21.

- Juen, C. M., M. Jankowski, R. A. Huber, T. Frank, L. Maaß, and M. Tepe. 2021. “Who Wants COVID-19 Vaccination to be Compulsory? The Impact of Party Cues, Left-Right Ideology, and Populism.” Politics, 02633957211061999.

- Jungkunz, S. 2021. “Political Polarization During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Frontiers in Political Science 6.

- Kerr, J., Panagopoulos, and Van Der Linden. 2021. “Political polarization on COVID-19 pandemic response in the United States.” Personality and individual differences 179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.110892.

- Kittel, B., S. Kritzinger, H. Boomgaarden, B. Prainsack, J. M. Eberl, F. Kalleitner, N. S. Lebernegg, et al. 2020. “Austrian Corona Panel Project (SUF Edition).” AUSSDA V4. https://doi.org/10.11587/28KQNS.

- Kittel, B., S. Kritzinger, H. Boomgaarden, B. Prainsack, J.-M. Eberl, F. Kalleitner, … L. Schlögl. 2021. “The Austrian Corona Panel Project: Monitoring Individual and Societal Dynamics Amidst the COVID-19 Crisis.” European Political Science 20 (2): 318–344. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-020-00294-7.

- Korn, L., R. Böhm, N. W. Meier, and C. Betsch. 2020. “Vaccination as a Social Contract.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117 (26): 14890–14899. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1919666117.

- Krings, V C, B Steeden, D Abrams, and M A Hogg. 2021. “Social attitudes and behavior in the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence and prospects from research on group processes and intergroup relations.” Group Processes and Intergroup Relations 24: 195–200. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430220986673.

- Kritzinger, Sylvia, Martial Foucault, Romain Lachat, Julia Partheymüller, Carolina Plescia, and Sylvain Brouard. 2021. “‘Rally Round the Flag’: The COVID-19 Crisis and Trust in the National Government.” West European Politics 44 (5-6): 1205–1231. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2021.1925017.

- Lipset, S. M., and S. Rokkan. 1967. “Cleavage Structures, Party Systems, and Voter Alignments: An Introduction.” In Party Systems and Voter Alignments: Cross-National Perspectives, edited by S. M. Lipset, and S. Rokkan, 1–64. Toronto: The Free Press.

- Maher, P. J., P. MacCarron, and M. Quayle. 2020. “Mapping Public Health Responses with Attitude Networks: The Emergence of Opinion-Based Groups in the UK’s Early COVID-19 Response Phase.” British Journal of Social Psychology 59 (3): 641–652. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12396.

- Malka, A., and Y. Lelkes. 2010. “More Than Ideology: Conservative–Liberal Identity and Receptivity to Political Cues.” Social Justice Research 23 (2): 156–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-010-0114-3.

- Motta, M., T. Callaghan, S. Sylvester, and K. Lunz-Trujillo. 2021. “Identifying the Prevalence, Correlates, and Policy Consequences of Anti-Vaccine Social Identity.” Politics, Groups, and Identities, 1–15.

- Paul, K. T., J.-M. Eberl, and J. Partheymüller. 2021. “Policy-relevant Attitudes Toward COVID-19 Vaccination: Associations with Demography, Health Risk, and Social and Political Factors.” Frontiers in Public Health 9.

- Peretti-Watel, P., V. Seror, S. Cortaredona, O. Launay, J. Raude, P. Verger, L. Fressard, et al. 2020. “A Future Vaccination Campaign Against COVID-19 at Risk of Vaccine Hesitancy and Politicisation.” The Lancet Infectious Diseases 20 (7): 769–770. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30426-6.

- Powdthavee, N., Y. E. Riyanto, E. C. Wong, J. X. Yeo, and Q. Y. Chan. 2021. “When Face Masks Signal Social Identity: Explaining the Deep Face-Mask Divide During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” PLoS One 16 (6): e0253195. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0253195.

- Rodriguez, C., S. K. Gadarian, S. W. Goodman, and T. Pepinsky. 2022. “Morbid Polarization: Exposure to COVID-19 and Partisan Disagreement About Pandemic Response.” Political Psychology.

- Rosenberg, S., C. Nelson, and P. S. Vivekananthan. 1968. “A Multidimensional Approach to the Structure of Personality Impressions.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 9 (4): 283. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0026086.

- Ruisch, B. C., C. Moore, J. Granados Samayoa, S. Boggs, J. Ladanyi, and R. Fazio. 2021. “Examining the Left-Right Divide Through the Lens of a Global Crisis: Ideological Differences and Their Implications for Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Political Psychology 42 (5): 795–816. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12740.

- Sprengholz, P., C. Betsch, and R. Böhm. 2024. “Experimental Testing of Three Categorization-Based Interventions to Reduce Prejudice and Discrimination Against the Unvaccinated in the Aftermath of COVID-19.” Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, https://doi.org/10.1111/asap.12386.

- Stamm, T. A., J. Partheymüller, E. Mosor, V. Ritschl, S. Kritzinger, A. Alunno, and J.-M. Eberl. 2023. “Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccine Fatigue.” Nature Medicine 29 (5): 1164–1171. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-023-02282-y.

- Stamm, T., J. Partheymüller, E. Mosor, V. Ritschl, S. Kritzinger, and J.-M. Eberl. 2022. “Coronavirus Vaccine Hesitancy among Unvaccinated Austrians: Assessing Underlying Motivations and the Effectiveness of Interventions Based on a Cross-Sectional Survey with two Embedded Conjoint Experiments.” The Lancet Regional Health – Europe in press.

- Stoetzer, L. F., S. Munzert, W. Lowe, B. Çalı, A. R. Gohdes, M. Helbling, R. Maxwell, and R. Traunmueller. 2021. “Affective partisan polarization and moral dilemmas during the COVID-19 pandemic.” Political Science Research and Methods 11 (2): 429–436.

- Tajfel, H., and J. C. Turner. 1979. “An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict.” In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations, edited by W. G. Austin, and W. Stephen, 33–47. Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole.

- Troiano, G., and A. Nardi. 2021. “Vaccine Hesitancy in the era of COVID-19.” Public Health 194: 245–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2021.02.025.

- Vignoles, V. L., Z. Jaser, F. Taylor, and E. Ntontis. 2021. “Harnessing Shared Identities to Mobilize Resilient Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Political Psychology 42 (5): 817–826. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12726.

- Wagner, M. 2024. “Affective Polarization in Europe.” European Political Science Review, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773923000383.