ABSTRACT

Within the broader discussion of US domestic terrorism, the impact of formal extremist groups on the behaviour of perpetrators of ideologically motivated crime stands as a key albeit under examined issue. Radicalization and terrorism have long been understood as group-driven processes, yet the degree and rate of group affiliation among US extremist offenders is highly variable, especially in the context of rising instances of lone actor attacks. This raises the question of the role that group affiliation plays in relation to perpetrators of extremist violence. For while discourse surrounding domestic terrorism has largely classified these organizations as facilitators or enablers of radicalization and extremist violence, patterns in recent years suggest these groups may in fact do the opposite and dampen the violent impulses of their members to preserve their organizational interests. This paper presents an analysis of data adapted from the Profiles of Individual Radicalization in the United States (PIRUS) dataset as well as original data and finds that membership in formal extremist groups does appear to create a moderating effect on perpetrators of ideologically motivated crime, reducing the probability of group members in engaging in violence.

Introduction

What is the contemporary role of formal extremist organizations in the landscape of US domestic terrorism and violent extremism and their effects on perpetrators of ideologically motivated crime? Over the past ten years, a series of high-profile acts has gradually shifted the attention of US counterterrorism stakeholders away from the transnational movements and groups that have been emblematic of the post-September 11 era. From lethal lone actor attacks in places like Pittsburgh and El Paso to the attack on the US Capitol Building on 6 January 2021, the threat of terrorism and violent extremism in the United States is increasingly being seen as something rooted in the home front as opposed to far-off enemies and conflicts. This has resulted in renewed debates on the role played by domestic extremist groups and movements and the degree to which they foster radicalization and violent extremism, with entities such as The Proud Boys, ANTIFA, Oath Keepers, and QAnon becoming practically household names. This approach to thinking about violent radicalization as a fundamentally group driven process is well grounded in existing research, which has historically understood it to be an inherently driven by social dynamics (Della Porta, Citation2018, Marwick et al., Citation2022), with several models of violent radicalization denoting recruitment by an extremist organization as an essential step in the process (Doosje et al., Citation2016). This understandably leads to the assumption that formal extremist organizations act as a force multiplier for violent extremism, resulting in radicalized individuals who are part of formal organizations being more prone to extremist violence than those who are not. Despite this however,

Much of this research, however, clashes with the recent patterns that are evident in the broader US landscape of extremist activity, as the degree to which US-based perpetrators of ideologically motivated crime are affiliated with formal extremist groups is highly variable, while more lethal acts of domestic terrorism are increasingly being carried out by lone actors, with minimal or non-existent ties to any formal group. This shift can be best explained by the contemporary structural characteristics of the environment in which US domestic extremist groups operate. For in contrast to many of their transnational counterparts, the overwhelming majority of domestic extremist groups are legal entities that operate more or less above ground and, at least publicly, do not openly call for extremist violence. This move is born as much out of necessity as anything else, as the threat of targeting and infiltration by law enforcement is constant and has been highlighted by many prominent extremist leaders as the primary reason why violence must be avoided on that part of organizations and their members (Hamm, Citation2002). In addition, these incentives for groups to keep their noses clean are complemented by the fact that the growth and evolution of extremist internet enclaves are now capable of providing many of the tools and techniques necessary for violent extremist that have historically only been accessible via access to formal groups. Individuals are now able to freely access everything from propaganda to attack plans to schematics for explosives and other weapons without even encountering a formal extremist group, let alone joining one. Consequently, the US domestic setting is increasingly characterized by formal extremist groups who have a powerful incentive to steer their members way from committing terrorism rather than towards it, all while those individuals who are committed to engaging in violence are less reliant on formal groups than ever before.

This paper will therefore test the hypothesis that, rather than being amplifiers of violent extremism among perpetrators of ideologically motivated crime and violence, US domestic extremist organizations instead work as dampeners and in fact reduce the propensity of offenders to commit extremist violence. This dampening effect is hypothesized to not only push group members to avoid violence entirely but also reduce the propensity for high lethality and indiscriminate use of violence among those members not prompted to eschew violence in its entirety. Using data drawn from The Profiles of Individual Radicalization in the United States (PIRUS) Project (National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, Citation2018), as well as original data gathered and compiled by the author, I present an analysis showing that among perpetrators of ideologically motivated crime in the United States, membership in an extremist organization is associated with a significant reduction in the likelihood of engaging in an act of extremist violence. I will begin with a brief review of the existing literature on radicalization and group versus individual dynamics and then move on to a description of the theory and research design.

Literature review

The impact of groups on extremist activity

While research and scholarship on violent radicalization continue to develop and evolve in meaningful ways, it is still fundamentally understood as a socially oriented process, stemming from “complex and contingent sets of interactions among individuals, groups, and institutional actors” (Della Porta, Citation2018). Radicalization is a gradual process of ideological development that does not occur in a vacuum, and those moving through the process will often come to reflect the identities and interpretations of a larger community as opposed to lone individuals (Marwick et al., Citation2022). And while not strictly speaking essential, formal groups and organizations can, and historically have had a powerful amplifying effect on these dynamics, as they can strengthen bonds between individual members, more clearly demarcate in-group/out-group relations, and encourage shared norms through social pressure (Borum, Citation2011).

Accordingly, the role of groups and formal extremist organizations occupies a prominent, albeit not always explicit place within existing theories of violent radicalization. Most are rooted in an analysis of environmental and social factors, and many draw significant influence from theories articulated to explain non-ideologically motivated criminal activity. Criminologists working under the umbrella of social control theory posit that criminal groups are essentially a collection of individuals who associate due to commonly held beliefs or personal deficits, and individuals can develop bonds that connect them with prosocial society and shield them from deviant relationships (Hirschi, Citation1969). Closely related to this is the idea of social bond theory, which highlights weakened bonds to mainstream society as a major contributor to non-conforming behaviour, as individuals will gravitate to other groupings and associations once they are effectively de-coupled from their immediate social environment (Hirschi, Citation1969, Sampson and Laub, Citation1996). M. H. Becker (Citation2021) established further empirical support for these findings via his analysis of the larger PIRUS database that will be utilized for the analysis of this project. That said, the work of Decker and Pyrooz (Citation2011) cast doubt on the degree to which criminological research can be applied in this context via their comparative analysis of extremist groups and criminal gangs that highlight key differences between the two, such as the fact that criminal gangs are often characterized “by undisciplined behavior, diverse offending patterns, and lack of discipline among their members.”

Within the broader literature on terrorism and extremism, however, both small groups and larger organizations are argued to exert a powerful motive force on extremist behaviour. These dynamics are clearly present in Sageman’s “bunch of guys” phenomenon, which stresses the dynamics of in-group affinity and out-group hatred as being instrumental to the process of radicalization (Sageman, Citation2011a, Citation2011b), and there is significant evidence that links extreme forms of violent expression and groupthink tendencies to this type of group dynamic (Bion, Citation2003; Janis, Citation1972; McCauley & Segal, Citation1989). Moghaddam places formal recruitment into a terrorist organization at the apex of his metaphorical staircase of radicalization and said organizations play increasingly important roles as one ascends. Specifically, organizations are responsible for “mobilizing sufficient resources to persuade recruits to become disengaged from morality as it is defined by government authorities (and often by the majority in society) and morally engaged in the way morality is constructed by the terrorist organization” (Moghaddam, Citation2005). Subsequent scholarship has iterated on this approach by placing formal membership in an extremist group as a key stage of the radicalization process itself, and one precipitating actual participation in terrorist violence (Doosje et al., Citation2016). The “two pyramid” model articulated by McCauley & Moskalenko works in a similar vein but is distinguished by its decoupling of radicalization of thought and radicalization of action (the two respective pyramids) as well as its rejection of the staircase model’s adherence to a clear and largely one-directional sequence of radicalization (McCauley & Moskalenko, Citation2017). Given the model’s assertion that radical thought does not directly lead to radical action, groups and organizations serve as both the motive force and primary unit of analysis for the action pyramid, for which terrorist violence serves as the pinnacle. This relationship is further supported by a range of extant theoretical and empirical work, the former by Reedy et al (Citation2013), who take this focus a step further and utilize small terrorist groups as the primary unit of analysis for mapping both behavioural dynamics as well as the articulation of a counterterrorism response framework, and the latter by both Adamczyk et al. (Citation2014) and Asal et al. (Citation2020), who establish the presence of hate groups and pre-existing histories of violence respectively as significant predictors of far-right violence. Analysis of similar data by Suttmoeller et al (Citation2018) however did not find any relationship between the participation of far-right groups in violence with group longevity.

In the context of these collective works, extremist groups and formal organizations can therefore be understood as focusing lenses or amplifiers for radicalization. Membership in an organization places individuals in an environment that both increases their exposure to extremist ideology and limits their view of alternative perspectives and information that may run counter to extremist narratives (Sunstein, Citation1999). In earlier scholarship, McCauley & Moskalenko compare the experiences of extremist group members to those of soldiers. Not only are both characterized by conditions of pronounced isolation, stress, and danger, but these collective conditions work to strengthen and reinforce group cohesion, values, and individual compliance (McCauley & Moskalenko, Citation2008). The problem is that research on this relationship between groups and violent radicalization has thus far been informed primarily by very particular terrorist movements operating in very particular environments, most notably International Jihadism and large-scale ethnonationalist movements such as those in Northern Ireland and Sri Lanka. This makes its conclusions difficult to apply to a contemporary US domestic context, which has increasingly seen terrorist violence being carried out by lone actors as opposed to those acting as part of organizations.

Group actors vs. lone actors

In contrast to the terrorist movements that informed much of the research described above, violent extremism in the context of the domestic United States has been increasingly characterized by lone actors. This trend solidified and continued throughout the 1990s and has continued to escalate since 2000, despite the fact rate of lone-actor terrorism in Europe has remained largely stable throughout this period (Spaaij and Hamm, Citation2015). This naturally raises the question as to whether formal extremist organizations in the United States play a role in violent radicalization similar to what is observed in the context of Jihadist and ethnonationalist movements outside the US. Efforts to provide an answer are complicated by the fact that research on lone actor terrorism has, at least historically, been beset by definitional, conceptual, and inference issues (Spaaij and Hamm, Citation2015, Smith et al, Citation2015). Even the term “lone actor terrorism” is somewhat misleading, as individuals that are classified as “lone actors” are not truly isolated from existing extremist communities, and often have a range of different ties with other individuals and networks (Lindekilde et al., Citation2019).

Despite these difficulties, scholarship has established several consequential differences between lone actors and those acting as part of an organization. In stark contrast to members of formal organizations, McCauley and Moskalenko (Citation2008) found that lone actors have been found to be more likely to suffer from mental illness or psychopathology. This finding was replicated by Gruenewald et al. (Citation2013), and found a significantly high correlation with military experience. Becker was also able to establish clear differences in targeting behaviour between lone and group actors, and found that lone actors opt for civilian targets far more often than their group counterparts and that their target selection is “overwhelmingly an ideologically driven process, as most lone wolves chose targets that clearly corresponded with the class of ‘enemies’ that they identified using their ideology” (M. Becker, Citation2014). These findings were further supplemented by Smith, Gruenewald, Roberts, and Damphousse who found that lone actors also engage in fewer precursor activities while at the same time appear willing to travel greater distances to carry out attacks (Smith et al, Citation2015). There are however mixed findings as to whether these differences translate to increased lethality however, as analysis by Alakoc looking at suicide attacks indicated that group attacks are significantly more lethal than those carried out by lone actors (Alakoc, Citation2017) while more recent analysis by Turner, Chermak, and Freilich looking at 230 terrorist homicide incidents found significantly severe outcomes associated with lone actors. Lastly, while somewhat counterintuitive, Gill et al. (Citation2014) found that while many lone-actor terrorists can be characterized by social isolation, they often engage in “a detectable and observable range of activities with a wider pressure group, social movement, or terrorist organization.” These findings are particularly noteworthy, as they not only push back against the image of the totally isolated “lone wolf,” but highlight the potential influence of weak/informal group ties in contrast to strong ones.

As for what is driving this US-based shift away from group-oriented terrorism towards a preponderance of lone actors, there are two general, albeit complementary explanations. The first is that it has been significantly prompted by enhanced capacity and escalated operations by domestic law enforcement that have made the operation of violent extremist groups untenable. This is illustrated most clearly via the large-scale adoption of the strategy “leaderless resistance” by a significant portion of the American far-right. Initially developed as a strategy for asymmetric warfare against a hypothetical communist invasion during the 1960’s, “leaderless resistance” serves as “a kind of lone wolf operation in which an individual, or a very small, highly cohesive group, engage in acts of anti-state violence independent of any movement, leader or network of support” (Kaplan, Citation1997, pg. 80). Following the targeting of several major far-right organizations by law enforcement during the late 1980s, which resulted in both significant legal action as well as the deaths of several prominent leaders, this tactic has been increasingly stressed as a necessary by many far-right extremists in order to guard against targeting and infiltration by state and federal law enforcement (Hamm, Citation2002).

The role of expanded law enforcement activities in prompting this move is clearly articulated by prominent white supremacist leader David Lane, who Robert Kaplan writes as stating: “Most basic is the division between the political or legal arm, and the armed party … The political arm will always be subjected to surveillance, scrutiny, harassment, and attempted infiltration by the system. Therefore, the political arm must remain scrupulously legal within the parameters allowed by the occupying power” (Kaplan, Citation1997). The sentiment can also be found in the writings of more contemporary far-right terrorists such as Anders Breivik who wrote, “Don’t trust anyone unless you absolutely need to (which should never be the case). Do absolutely everything by yourself” (Breivik, Citation2011)). This shift towards more decentralized operations was also not unique to the American far-right, as in 2008 Sageman argued that the global Jihadist movement had moved towards a strategy of “leaderless Jihad,” transitioning towards operating as a network of self-organized actors rather than relying on large formal organizations such as al-Qaeda (Sageman, Citation2011b). These developments are also consistent with the findings of Enders and Su, who found that terrorist movements will often work to “counter increased efforts at infiltration and restructure themselves to be less penetrable” (W. Enders & Xuejuan, Citation2007). This all points towards a large segment of potentially violent domestic extremist organizations operating under the belief that US law enforcement has effectively created an environment where large, formal organizations are not seen as viable avenues for individuals and movements looking to engage in terrorist violence.

The second development that has enabled the shift away from group-oriented terrorism is the development and rapid evolution of internet technology and social media networks, which has created an environment where extremist actors are much less reliant on formal organizations for many of their organizational and logistical needs. Steven and Neumann (Citation2009) highlight three key ways in which the internet has revolutionized the process of radicalization. First, it provides potential recruits near-instantaneous access to potent rhetoric, video, and imagery, providing easy reinforcement and substantiation for extremist political claims and messages. Second, it significantly lowers the costs of engaging with, joining, and integrating with formal and informal organizations and movements, as the process of seeking out like-minded individuals is, more or less, risk-free. And third, it creates new social environments where otherwise unacceptable views, ideologies and behaviours can be normalized (the “echo chamber” effect). The internet can therefore be viewed as a means of circumventing the proximity requirements inherent in the previously described theories, as the “bunch of guys” can be spread across hundreds or even thousands of miles, and further exacerbating perceived in-group and out-group divisions. Additionally, the online nature of these communities has been shown to allow for much higher levels of ideological reinforcement, as the constant interactions between individuals and their online acquaintances increases both the retention and credibility of the message (ibid.; Venhaus Citation2010). In contrast to a local Klan chapter or neo-Nazi group of the 1970’s that might meet once a week, social media now allows individuals to be in contact almost continuously.

Evidence supporting this transformative role of the internet has been developing for some time. As early as 2007, The NYPD Intelligence Division claimed to have identified the Internet as a “driver and enabler for the process of radicalization” (Silber & Bhatt, Citation2007). A RAND corporation report (Von Behr et al., Citation2013) gives further support to the role of the internet as a potent pathway or vector for the radicalization processes by: creating more opportunities to become radicalized; providing an “echo chamber” (a place where individuals find their ideas supported and echoed by other like-minded individuals); allowing radicalization to occur without physical contact; and increasing opportunities for self-radicalization. One of the advantages of this development, however, is that while these internet enclaves can be reclusive, many are still accessible to outside observers in ways that Sageman’s “bunches of guys” are not. Along these lines, Gaudette et al (Citation2022) utilized a series of interviews with former members of violent racist skinhead groups in Canada that overwhelmingly highlight the internet as a key role in the interviewees’ violent radicalization. Yet their size, frequent preference for user anonymity, and highly decentralized nature mean that this accessibility does not necessarily translate to vulnerability in terms of interdiction.

The result is that the expansion of domestic law enforcement coupled with increased capacity of internet networks have created an environment where formal extremist organizations no longer play their traditional role in terms of fostering and amplifying violent radicalization. Not only do these groups make for lucrative targets for law enforcement, but the more decentralized modes of mobilization and radicalization offered by the internet provide many of the traditional advantages of formal groups in terms of organizational capacity and communication while at the same time being much less vulnerable to interdiction. This implies a certain degree of obsolescence for formal extremist groups in a domestic US context, yet despite these developments, these groups remain incredibly prevalent, with the Southern Poverty Law Center designating a record 1,020 active hate groups in 2018. As of 2021, this number fell to 733, although the SPLC attributes this primarily to the increased mainstreaming of far-right ideology in domestic US politics (SPLC, Citation2022). This then raises the question: considering these structural shifts, what role do these groups play in the behaviour of those engaging in ideologically motivated crime?

Theory and research design

Bearing in mind the developments described above, it is the opinion of the author that the effects of membership in formal US domestic extremist groups have shifted, and rather than being enablers of violent extremism they have become inhibitors of such behaviour on the part of their members. As was described previously, violent radicalization has traditionally been understood as a socially driven process that is greatly facilitated by environmental and social variables a particular individual is exposed to. Regardless of whether the process is conceptualized as a “staircase”, a “pyramid”, or a “bunch of guys”, immersion into extremist social circles, either in-person or virtually, should logically serve as a significant vector for violent radicalization. Consequently, explicit membership or affiliation with extremist organizations should be viewed as a significant radicalization accelerant that works to increase the likelihood of an individual engaging in extremist violence.

This assumption however overlooks the environment in which contemporary American extremist groups and movements operate and the ways in which US extremist movements have evolved in recent decades. With the notable exception of transnational terrorist organizations that are formally designated as such by the State Department’s Bureau of Counterterrorism, US-based extremist groups are largely legal entities that often do not operate in an overtly clandestine fashion. Even groups with a long history of terrorist activity such as the Ku Klux Klan are to a certain degree “public facing” and do not seek to evade the state in the way extremist groups do in less open legal environments. Additionally, contemporary groups that are being actively targeted and prosecuted by federal law enforcement, such as the Proud Boys and Oath Keepers, whose leaders have been formally charged with seditious conspiracy for their role in the January 6th Riots at the US Capitol, remain legal entities and associations.

Consequently, the leadership of US extremist groups often tends to take a firm rhetorical line against the use of political violence on the part of their members or other affiliated groups, with many often condemning attacks carried out by lone actors associated with the movement. For example, in the wake of being prominently cited in the manifesto of Dylann Roof, perpetrator of the 2015 attack on the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston South Carolina, the white supremacist organization The Council of Conservative Citizens moved to completely disassociate with Roof. Five days after the attack which left nine people dead, a spokesman for the group sought to draw a very clear line, stating: “No one in the organization that I know of … has ever heard of (Roof). He certainly was never a member, and I don’t suspect that he ever attended a meeting. Our site educated him. Our site told him the truth about interracial crime. What he then decided to do with that truth is absolutely not our responsibility” (The Associated Press, Citation2015). Additionally, even groups that are merely tangentially related to terrorism perpetrators will often take steps to create as much distance as possible. Shortly after the 2019 attack on an El Paso Walmart that killed 23 people, a manifesto attributed to shooter Patrick Crusius described the attack as being motived by the white supremacist “great replacement theory” and consequently he specifically sought to target Latinos for their perceived role in the replacement of white Americans. This prompted the leaders of the anti-immigration groups The Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR) and The Center for Immigration Studies (CIS), two groups founded by white nationalist John Tanton and designated as hate groups by the Southern Poverty Law Center, to come out and issue statements condemning the attack, despite in no way being concretely linked to Crucius (Nakamura, Citation2019).

While there are multiple potential explanations for this approach, such as fear of being targeted by law enforcement or commitment to a broader “hearts and minds” agenda that association with terrorism could compromise, the degree to which extremist group membership functions as an accelerant for terrorist activity in a US domestic context is, in this light, somewhat questionable. Regardless of the motivation, however, involvement in political violence on the part of US domestic extremism organizations is a risky proposition and presents a range of different hazards to any given group. These hazards are also likely to be proportional to the scale of the violence a particular group is linked to. Although all links to violence present risks to an organization, acts characterized by indiscriminate or high-lethality violence are far and away more hazardous to groups in terms of negative attention from law enforcement, the media, and the public. A member of a white power organization who assaults an ethnic minority in the street may bring trouble from local police, but attacks like the ones seen in Buffalo, Charleston, El Paso, and elsewhere promise to bring to full weight of federal law enforcement and the national media to bear against any entity that is meaningfully linked to it. That being said not all extremist organizations of a piece, and it stands to reason that groups and movements that are more public-facing or involved with above-ground political activism will be far more sensitive to these risks than smaller and more informal groupings of extremists.

Therefore, in regard to extremist acts that result in public acts of mass violence, membership in formal organizations or larger above-ground extremist movements may actually work to disincentivize such action rather than encourage it. Given the need and desire for these organizations to maintain the “public facing” stance described above, it makes sense that leaders would stress this imperative to their members. Group membership would therefore lower the likelihood of a radicalized individual engaging in acts of overt or indiscriminate extremist violence, given that such activities would likely disrupt group operations, tarnish the group’s public image, or potentially cause the group to be targeted by law enforcement. Additionally, even in cases where group members do engage in violence, it is reasonable to hypothesize that this organizational dampening effect may still exert a degree of influence, and result in members of formal organizations pursuing violent actions with lower projected lethality than those who lack organizational ties. The following analysis with therefore look to test two primary hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1:

Among perpetrators of ideologically motivated crime, individuals who are members of formal extremist organizations or movements are less likely to commit acts of indiscriminate violence.

Hypothesis 2:

Among perpetrators of ideologically motivated crime, individuals who are members of formal extremist organizations or movements are less likely to be involved in plots that would result in high levels of lethality.

To summarize: in order to continue to operate in a public and legal fashion, formal US domestic extremist organizations and movements have a strong incentive to both abstain from engaging in terrorism and distance themselves from those that do and subsequently stress this imperative to their respective members. This incentive produces a dampening effect on group members, resulting in extremists who are members of formal organizations or movements being less likely to engage in indiscriminate or high-lethality acts of violence than those who are not. These hypotheses will be tested via quantitative analysis of a mix of existing and unique data compiled for this project.

Methodology

Data

These hypotheses will be tested utilizing data that is principally based on The Profiles of Individual Radicalization in the United States (PIRUS) project developed by The National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START). Covering the entire United States from 1948–2017, PIRUS presents offender-level data on violent and non-violent extremists across a range of ideologies with a focus on background, attributes and radicalization processes coded entirely using open-source information (START, Citation2018). In order to be eligible for inclusion, offenders must meet one the following five criteria: (1) the individual was arrested, (2) the individual was indicted of a crime, (3) the individual was killed as a result of his/her ideological activities, (4) the individual is/was a member of a designated terrorist organization, (5) the individual was associated with an extremist organization whose leader(s) or founder(s) has/have been indicted of an ideologically motivated violent offence. Additionally, for all those included there must be sufficient evidence that they: (1) have been radicalized in the United States, (2) have espoused or currently espouse ideological motives (Islamist, far-right, far-left, or single issue), and (3) show evidence that his/her behaviours are/were linked to the ideological motives he/she espoused/espouses. This dataset comprises ~ 2,200 individuals with a range of offender-level variables capturing plot and activity data, information dealing with their radicalization and group affiliation, as well as demographic and socio-economic data.

These data served as the foundation of a secondary coding effort aimed at both rectifying issues present in the original data and capturing a much more detailed picture of each offender’s ideologically motivated activities. The temporal range was first shortened to 1990–2017. This was intended to account for major differences in domestic extremist activity prior to and after the 1990s (such as the rise of Islamic radicalization and the overall waning of Cold War-era militant Leftism), as well the fact that relevant information on post-1990 cases tend to be both more prevalent and more accessible, as much of the missing data from PIRUS was clustered around the pre-1990 period. This pool of individuals was further reduced on a case-by-case basis to account for those who did not warrant inclusion in this analysis due to the nature of their activities (or lack thereof). Examples of this include the leader of white nationalist group who was included in PIRUS due to their group association but could not be linked to any criminal behaviour, as well as individuals who engaged in criminal behaviour that could not reasonably be classified as “ideologically motivated,” such as weapons charges not linked to any specific plot, criminal, or violent activity. In addition, individuals who were charged with terrorism or related activities but were later ruled to have been victims of entrapment by law enforcement were also removed. An example of this was a case from 2014, where the FBI sought to entrap an American whose name was found in a notebook that was recovered from an Al Qaeda training camp that detailed significant financial offerings. Lastly, the dataset included several US citizens who were charged in association with overseas/transnational extremist activity, such as travelling to train at an ISIL training camp in Syria or seeking to target US forces and assets abroad. Given this project’s focus on domestic activity and constraints, these individuals were removed from the dataset. These efforts reduced the number of total offenders by roughly half, resulting in a final pool of 1,064 individuals.

This pool was then subjected to an extensive coding schema aimed at providing detailed information on each offender’s extremist activity specifically regarding violence. The original PIRUS coding captures violence as a dummy variable, which while useful, does not necessarily encompass the degree of variation in the activities within the data. Teenagers who set fire to a synagogue, a white nationalist who attacks and beats a non-white person he encounters on the street, and an accelerationist neo-Nazi who executes a mass casualty attack with long guns and explosives all fall under the umbrella of “violent activity,” but it would be a significant over-simplification to assert no meaningful difference between them. Therefore, a new variable was added to capture those offenders who engaged in or actively sought to engage in indiscriminate violence. For our purposes, indiscriminate violence refers to any premeditated activity that aims to produce human casualties beyond a single target and lacks any consideration of bystanders or collateral damage. The primary purpose of this distinction is to separate violent activities that can reasonably be classified as terrorism, such as mass shootings and bombings, from both interpersonal and targeted violence, such as violence stemming from inter-movement competition or a white supremacist assaulting a minority while under the effects of drugs and alcohol, as well as actions where the goal is property damage rather killing or injuring, such a radical environmental group setting fire to a construction site after-hours. This variable also excludes all individuals whose activities were discovered during planning or development and includes only those offenders who either successfully executed an act of indiscriminate violence or were interdicted by law enforcement en route to or in the process of carrying it out. An example of the latter would be the case of Michael Finton in 2009, who was arrested by law enforcement while attempting to detonate explosives at the Paul Findley Federal Building and Courthouse.

Variables

All variables utilized in the analysis are drawn from the modified PIRUS data described above. Each observation captures data on one of the 1,064 individuals that make up the modified dataset. Hypothesis oneFootnote1 will be tested via two models utilizing different dependent variables. The first will utilize the “violent” variable from the base PIRUS dataset, which is a dichotomous variable denoting whether the individual in question participated in any operations or actions that either resulted in or intended to result in death or injury (1 for violent, 0 for non-violent), while the second model will utilize the indiscriminate violence variable described above. Like the base PIRUS violent variable, indiscriminate violence is a dichotomous variable with “1” denoting that the offender utilized or intended to utilize violence in an indiscriminate manner as described above, meaning that they did not seek to confine their violent actions to a specific individual but rather exposed any individuals within the proximity of their actions to injury or death. The model utilizing the base PIRUS violence variable is meant to serve as a point of comparison to test the theoretical assumption that the effects of group membership are more effective in preventing more extreme acts of violence compared to more limited ones. The model testing hypothesis twoFootnote2 will utilize data from the base PIRUS dataset on anticipated fatalities as its dependent variable. This variable estimates the range of fatalities each offender sought to inflict along a four-point scale: “0” denotes no intended fatalities or no involvement in a violent plot, “1” corresponds to 1–20 fatalities, “2” greater than 20, and “3” greater than 100. The ordinal nature of this variable (as opposed to count) is due to a significant number of observations being based on estimates derived from credible plots that were interdicted by law enforcement, and therefore needed to be extrapolated via interpretations of the offender’s intent, capabilities, and the predicted impact of their actions.

The primary independent variable for the analysis, namely group membership, is taken directly from the primary PIRUS dataset and captures four distinct classifications. A score of “0” stipulates that the individual in question was not a member of any group or movement. “1” denotes either a member of an informal group of extremists, akin to a home-grown cell or informal militia, or someone with informal links to a larger organization. An example of the former would be the Sovereign Citizens movement, as it is a loose grouping of likeminded individuals but lacking any formal organizational structure, while an example of the latter would be Al Saleh, a New York man who, in 2013, was charged with operating in support of the Islamic State despite having no formal ties to the group. A score of “2” denotes a member of a formal extremist organization or movement, such as the Animal Liberation Front or Al Qaeda. Individuals in this category, in contrast to informal membership, can be credibly linked to the formal structures of whatever group they are affiliated with. Lastly, a score of “3” captures individuals who can be clearly established as members of above-ground political movements or activist groups, such as Operation Rescue or Earth First! The crucial differentiation between these movements and the formal organizations described prior is that above ground political movements are characterized as being significantly engaged in legal, public-facing political activity, such as protests, lobbying, or general activism. The PIRUS coding for this variable is remarkably complete, and no missing data is present for the entire 1,064-person sample utilized for this analysis. It also bears noting that this variable only denotes the nature of the organization each individual was affiliated with, assuming they had any affiliation at all. While doubtless of interest, things such as the details of the relationship between each offender and organization or whether they acted with or without the sanction of the organization could not be determined in a comprehensive manner and are therefore outside the scope of this study.

It is however acknowledged that this variable alone is an imperfect instrument for testing the full impact of group membership on individual behaviour, as it does not capture a range of consequential data such as group organizational structure, group size, group age, etc. But while doubtless of strong theoretical importance, the acquisition of these data is highly problematic. For in contrast to comparatively large transnational groups such as Al Qaeda and the Islamic State, establishing things such as organizational size for many US-based extremist groups, especially smaller and more informal ones, is extraordinarily difficult outside the context of rigorous ethnographic work. Consequently, attempting to incorporate these variables would result in so much missing data as to make them functionally useless as instruments. As a partial remedy for this issue, each organization and group in the dataset was numerically encoded and used to cluster the analysis of all three models to control for group-level characteristics. An additional dummy variable was also added that denotes whether each group was on the US State Department Foreign Terrorist Organizations (FTO) list at the time of the incident in order to account for potentially heightened scrutiny from law enforcement.

Lastly, numerous control variables are included in all three models, with some taken from the primary PIRUS dataset and others generated for this analysis. Firstly, ideological variables for far-right and Islamist actors are included to account for both their contemporary prominence in the US extremist landscape as well as general clustering around specific ideologies, as existing research indicates a relationship between ideological differences and terrorist lethality (Asal & Rethemeyer, Citation2008). Each is a dummy variable captures whether the offender became radicalized as part of a right-wing or Islamist movement respectively. Second, the PIRUS variable on previous criminal activity was re-coded into a dummy variable that captures whether each offender had previously engaged in violent crime, as a history of violent criminal behaviour can potentially be viewed as part of a larger process of escalation, potentially culminating in indiscriminate extremist violence. The role of escalation is explicit in McCauley and Moskalenko’s (Citation2017) two-pyramid model, which stresses the progressive path of radicalization. Third, a range of different variables are used to account for potential social control factors that could also theoretically serve as inhibitors to violent activity. “Marital status” was captured via a broad categorical variable in the core PIRUS data and was re-coded as a dummy variable denoting whether the offender was married or not at the time of the incident. Similarly, the multi-point “employment status” and “military service” variables were also transformed into dummy variables denoting whether the offender was employed at the time of the incident or was ever a member of the military respectively. The analysis also includes two variables from the base PIRUS to account for technological development over the temporal course of the sample. The first captures internet radicalization, which is a three-point scale ranging from: no known role of the internet in the individual’s radicalization (0), the internet played a role but was not the primary means of radicalization (1), and the internet was the primary means of radicalization for the individual (2). The second deals with the degree to which social media and online communities contributed to the radicalization process. This variable is distinct from internet radicalization, as it captures user-to-user communication as opposed to passive exposure to extremist material hosted online. Both variables work to account for online networks and resources subbing in for the role traditionally played by formal organizations. Full descriptive statistics for all variables can be found in .

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

The analysis is however complicated by the fact that, with the exception of the control variables capturing ideology, all other control variables suffer from a high degree of missingness, ranging from 30% at the low end to 62% at the high end. This presented a significant problem as utilizing the data as is reduced the total number of observations available to the analytical models from 1,064 to just 166, and there is no inherently correct methodological procedure for addressing this amount of missing data (C. K. Enders, Citation2010). The use of multiple imputation to estimate the values of the missing data was considered but ultimately not pursued as I cannot assert with any confidence the randomness of the missing data due to its reliance on open-source data as well as human coders. In the end I opted for a somewhat blunter approach. For each control variable, missing values were re-coded as the base value for each. For example, each missing observation for the internet radicalization variable was re-coded as “0,” denoting “no known role of the internet in radicalization,” while missing observations for “marital status” were re-coded as “0,” denoting “single.” As a precaution, prior to re-coding, each control variable was added to a standalone model featuring only the primary independent and dependent variables to serve as a comparison to the primary analytical models. In every case, the direction and statistical significance of the independent variable remained constant between the primary and control models. While imperfect, I am confident that this is a reasonable solution to the missing data problem. The full variable layout is therefore as follows:

Analysis methodology

Given that the dependent variable for models 1 and 2 is dichotomous, each utilizes a logistic regression with robust standard errors. As projected lethality is measured via an ordinal dependent variable with values categorically ordered based on severity, model three utilizes an ordered logistic regression with “0,” denoting no intended fatalities, serving as the reference value. Across all three models, “group membership” is treated as a factor variable, allowing for results on each of its three primary values, with zero (denoting no group membership) serving as the reference value. As was previously stated, all three models cluster their analysis around individual groups to control for unobserved organizational differences. Lastly, as the use of logistic regressions precludes the direct interpretation of coefficients, the “margins” function in STATA is used to calculate and plot the effects of the independent variable coefficients, with the values of the control variables all being held at their means. Additionally, the substantive effects on predicted probability due to group membership are presented and graphed with 95% confidence intervals. For all analytical models, chi-squared tests were significant at p < 0.0001

Findings

contains the results of all three analytic models and contain the substantive effects of each level of group affiliation on the model’s predicted probability with all other variables held at their means. Several findings are immediately apparent. To begin with the logit model utilizing the base PIRUS violence measure as its dependent variable. As was stated above, this model is primarily designed to serve as comparison point to aid in the testing of hypothesis one. While there is slight variation in statistical significance, the direction and strength of the coefficients for the primary covariate and most of the control variables are consistent across both models.

Table 2. Analysis results.

Table 3. Substantive effects for models 1 and 2.

Table 4. Substantive effects for Model 3.

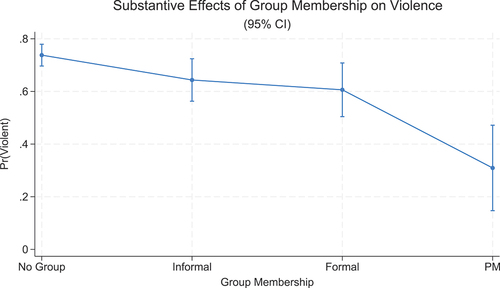

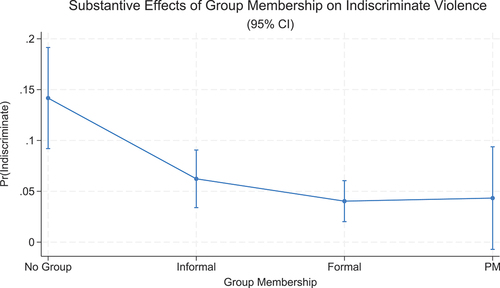

Taken collectively, the results of models 1 and 2 establish fairly strong support for hypothesis one, albeit somewhat more questionable support for hypothesis two. Across both models, every level of group or organizational affiliation is negatively correlated with the respective violent outcome variable. The strongest and most robust finding in this regard is the effect of membership in an above-ground political movement, which is highly statistically significant across both the base PIRUS violence and indiscriminate violence models and corresponds to a massive drop-off in the predicted probability of violence, 73% to 31% and 14% to 4% respectively. Taken on its own, the indiscriminate violence model establishes strong support for the dampening effects of any form of group or organizational affiliation, as the introduction of even informal group membership reduces the probability of engaging in indiscriminate violence by over 50%. The idea that the likelihood of violence drops with each successive level of organizational affiliation is also supported by the results of both models, despite each model having different drop-off points, with base-violence seeing its primary drop with the jump from formal group to political movement while indiscriminate violence drops between no group affiliation and informal. Taken collectively, these findings provide significant evidence linking membership in extremist organizations to a lower propensity to commit terrorism and extremist violence and indeed point towards domestic extremist groups producing a dampening effect on its members. Additionally, the shifts in the predicted probabilities in both model given partial evidence that the strength of a given group’s dampening effect on extremist violence intensifies as they become more mainstream. See and for a description and plot of the adjusted predictions at a 95% confidence interval.

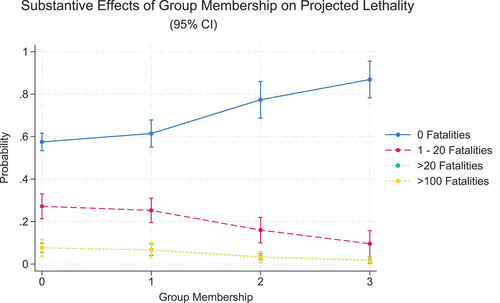

The results of model three, examining actual and projected lethality, provides affirmative albeit much more limited support for hypothesis two. While the coefficients for all three levels of organizational affiliation remain negative, only membership in formal extremist organizations and political movements have a statistically significant relationship to lethality, with membership in both informal groups falling well short. It is however noteworthy that the significance of formal group and political movement membership are highly robust and their effects on the model’s predicted probabilities are consistent with the trends present in models 1 and 2. This is most evident in the comparative effects of formal group versus political movement member, with the probability of involvement dropping by between 40 and 50% when moving to higher categories of lethality. That said, this model is by far the most constrained due to the nature of the dependent variable, which is, at its core, highly speculative and significantly informed by what the anticipated result of the offender’s actions would be. I would therefore classify the support for hypothesis two as partial and recommend additional study on this relationship and the development of more fine-grained data that will enable a more robust analysis. Plots of this model’s adjusted predictions can be found in .

Beyond the findings relevant to the project’s two hypotheses, the models’ control variables did produce several noteworthy results, primarily those capturing far right and Islamist ideological alignment. Interestingly, while both ideological control variables are highly significant and positive in model one, their significance completely disappears in model two, with only partial positive significant for Islamism in model three. The results for far-right radicalization are perhaps most noteworthy and certainly out of step with the overwhelming consensus in both academia and media that far right ideology serves a significant, if not the most significant motivator of US domestic terrorism and violent extremism. There are however several possible explanations for this. First, it be a consequence of the data’s temporal scope only extending to 2017, and as a result does not capture many of the higher-profile acts of far-right terrorism that have characterized the intervening period. Additionally, model two’s exclusion of both plots and interpersonal violence, the latter especially accounting for a significant portion of far-right violence, may also account for the shift in significance. It is therefore difficult to consider these findings as clear evidence as to the effects of far-right extremism on US domestic terrorism and recommend further research and analysis once more current data is available. That being said, some aspects of these results are consistent with the findings detailed in Asal and Vitek (Citation2018) that found ideological differences to have a minimal impact on extremist violence broadly defined via analysis of a sample of violent and non-violent domestic extremist organizations. Beyond the ideological variables, the results for the remaining controls provide limited insight due to the volume of missing data.

Conclusion

The findings presented here offer several consequential takeaways. First, this analysis provides powerful evidence for how the role of formal extremist organizations should be understood in the context of US domestic terrorism. Despite their predominance in much of the existing literature, the findings presented here indicate that they are not the primary vehicle of violent radicalization in the context of the contemporary United States. And while it is hardly the intent of the author that groups of the kind should be viewed as in any way a net-positive, it is important to acknowledge that the landscape of radicalization has shifted in important ways, and many of the actors that have historically been key players in explaining violent extremism may no longer play the same role. Both researchers and policy stakeholders need to contend with the fact that violent radicalization is increasingly the product of movements and communities that are far more diffuse and decentralized than those that have historically produced terrorist actors and spread across any number of counties, websites, and affiliations. And despite the fact that the individuals who emerge from these communities and commit terrorist do not act as part of an organization, the degree to which we can truly view them as lone actors is questionable. One need only look at the far-right attack in Buffalo, New York in May of 2022, the perpetrator of which modelled his actions so closely to the 2019 Christchurch attack in New Zealand that he went so far as to plagiarize 28% of the Christchurch shooter’s manifesto in his own (Kriner et al, Citation2022).

Second, the continued study of the role of extremist groups would be well served via the continued expansion of available data. As was mentioned earlier in the paper, the temporal scope of the PIRUS dataset and the supplemental coding analysed here do not go beyond 2018 and bringing it up to date would enable the robustness of these findings to be strengthened significantly given the broad spectrum of violent extremism the US has experienced since. This expansion would ideally be coupled with more detailed data collection on US-based extremist organizations, in order to allow for more detailed analysis of the role of group-level characteristics. Additionally, further research would also benefit from replicating this analysis in a Western European context. Countries such as the United Kingdom and Germany not only feature similar legal landscapes in terms of formal extremist groups but are also home to a similar spectrum of extremist ideologies and actors. A comparative analysis of this type would likely be highly fruitful, especially given that Europe has not experienced a comparable shift towards lone actor terrorism (Spaaij, 2010). It would also provide another avenue to test the effects of specific extremist ideologies, as the findings presented here on that front are consistent with existing analyses while inconsistent with others.

Lastly, the theory developed in this paper is extremely well positioned to be tested further with more qualitative methodologies, ideally in the form of interviews with current or extremist group members. While organizing such a project is certainly easier said than done, as securing willing and appropriate interview subjects poses a raff of potential difficulties, it would have the potential to produce extremely fine-grained data that would allow researcher to better pinpoint the causal effects of group membership on domestic extremists.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Hypothesis 1: Among perpetrators of ideologically motivated crime, individuals who are members of formal extremist organizations or movements are less likely to commit acts of indiscriminate violence.

2. Hypothesis 2: Among perpetrators of ideologically motivated crime, individuals who are members of formal extremist organizations or movements are less likely to be involved in plots that would result in high levels of lethality.

References

- Adamczyk, A., Gruenewald, J., Chermak, S. M., & Freilich, J. D. (2014). The relationship between hate groups and far-right ideological violence. Journal Of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 30(3), 310–332. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043986214536659

- Alakoc, B. P. (2017). Competing to kill: Terrorist organizations versus lone wolf terrorists. Terrorism And Political Violence, 29(3), 509–532. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2015.1050489

- Asal, V., Chermak, S. M., Fitzgerald, S., & Freilich, J. D. (2020). Organizational-level characteristics in right-wing extremist groups in the United States over time. Criminal Justice Review, 45(2), 250–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734016815626970

- Asal, V., & Rethemeyer, R. K. (2008). The nature of the beast: Organizational structures and the lethality of terrorist attacks. The Journal Of Politics, 70(2), 437–449. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381608080419

- Asal, V., & Vitek, A. (2018). Sometimes they mean what they say: Understanding violence among domestic extremists. Dynamics Of Asymmetric Conflict, 11(2), 74–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/17467586.2018.1470659

- Becker, M. (2014). Explaining lone wolf target selection in the United States. Studies In Conflict & Terrorism, 37(11), 959–978. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2014.952261

- Becker, M. H. (2021). When extremists become violent: Examining the Association Between Social Control, Social Learning, and engagement in violent extremism. Studies In Conflict & Terrorism, 44(12), 1104–1124. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2019.1626093

- Behr, I. V., Reding, A., Edwards, C., & Gribbon, L. (2013). Radicalisation in the digital era: The use of the internet in 15 cases of terrorism and extremism. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corperation.

- Bion, W. R. (2003). Experiences in groups: And other papers. Routledge.

- Borum, R. (2011). Radicalization into Violent Extremism I: A Review of Social Science Theories. Journal Of Strategic Security, 4(4), 7–36. https://doi.org/10.5038/1944-0472.4.4.1

- Breivik, A. B. (2011). A European declaration of independence. Retrieved December, 6(2013), 2010–2019.

- Decker, S., & Pyrooz, D. (2011). Gangs, terrorism, and radicalization. Journal Of Strategic Security, 4(4), 151–166. https://doi.org/10.5038/1944-0472.4.4.7

- Della Porta, D. (2018). Radicalization: A relational perspective. Annual Review Of Political Science, 21(1), 461–474. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-042716-102314

- Doosje, B., Moghaddam, F. M., Kruglanski, A. W., de Wolf, A., Mann, L., & Feddes, A. R. (2016). Terrorism, radicalization and de-radicalization. Current Opinion In Psychology, 11, 79–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.06.008

- Enders, C. K. (2010). Applied missing data analysis. Guilford press.

- Enders, W., & Xuejuan, S. (2007). Rational terrorists and optimal network structure. Journal Of Conflict Resolution, 51(1), 33–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002706296155

- Gaudette, T., Scrivens, R., & Venkatesh, V. (2022). The role of the internet in facilitating violent extremism: insights from former right-wing extremists. Terrorism and Political Violence, 34(7), 1339–1356.

- Gill, P., Horgan, J., & Deckert, P. (2014). Bombing alone: Tracing the Motivations and antecedent behaviors of Lone‐Actor terrorists. Journal Of Forensic Sciences, 59(2), 425–435. https://doi.org/10.1111/1556-4029.12312

- Gruenewald, J., Chermak, S., & Freilich, J. D. (2013). Distinguishing ‘loner’ attacks from other domestic extremist violence. Criminology & Public Policy, 12(1), 65–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12008

- Hamm, M. S. (2002). In bad company: America’s terrorist underground. Upne.

- Hirschi, T. (1969). Causes of delinquency. University of California.

- Janis, I. L. (1972). Victims of Groupthink: A psychological study of foreign-policy decisions and fiascoes. Houghton, Mifflin.

- Kaplan, J. (1997). Leaderless resistance. Terrorism And Political Violence, 9(3), 80–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546559708427417

- Kriner, M., Barbarossa, E., & Bernardo, I. (2022). The Buffalo Terrorist Attack: Situating Lone Actor Violence into the Militant Accelerationism Landscape. MIddlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey: The Center on Terrorism, Extremism, and Counterterrorism. https://www.middlebury.edu/institute/academics/centers-initiatives/ctec/ctec-publications/buffalo-terrorist-attack-situating-lone-actor

- Lindekilde, L., Malthaner, S., & O’Connor, F. (2019). Peripheral and embedded: Relational patterns of lone-actor terrorist radicalization. Dynamics Of Asymmetric Conflict, 12(1), 20–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/17467586.2018.1551557

- Marwick, A., Clancy, B., & Furl, K. (2022). Far-Right Online Radicalization: A Review of the Literature. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

- McCauley, C., & Moskalenko, S. (2008). Mechanisms of political radicalization: Pathways toward terrorism. Terrorism And Political Violence, 20(3), 415–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546550802073367

- McCauley, C., & Moskalenko, S. (2017). Understanding political radicalization: The two-pyramids model. American Psychologist, 72(3), 205–216. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000062

- McCauley, C. R., & Segal, M. E. (1989). Terrorist individuals and terrorist groups: The normal psychology of extreme behavior.

- Moghaddam, F. M. (2005). The staircase to terrorism: A psychological exploration. American Psychologist, 60(2), 161–169. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.60.2.161

- Nakamura, D. (2019). ‘It had nothing to do with us’: Restrictionist groups distance themselves from accused El Paso shooter, who shared similar views on immigrants. Washington Post. Accessed August 31, 2022. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/it-had-nothing-to-do-with-us-restrictionist-groups-distance-themselves-from-el-paso-shooter-who-shared-similar-views-on-immigrants/2019/08/08/c44dd7f8-b955-11e9-a091-6a96e67d9cce_story.html

- National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START). (2018). Profiles of Individual Radicalization in the United States [data file]. Retrieved from http://www.start.umd.edu/pirus

- Reedy, J., Gastil, J., & Gabbay, M. (2013). Terrorism and small groups: An analytical framework for group disruption. Small Group Research, 44(6), 599–626. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496413501892

- Sageman, M. (2011a). Leaderless jihad: Terror networks in the twenty-first century. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Sageman, M. (2011b). Understanding terror networks. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Sampson, R. J., & Laub, J. H. (1996). Socioeconomic achievement in the life course of disadvantaged men: Military Service as a turning point, circa 1940-1965. American Sociological Review, 61(3), 347. https://doi.org/10.2307/2096353

- Silber, M. D., & Bhatt, A. (2007). Radicalization in the west: The homegrown threat. The New York City Police Department, 92.

- Smith, B. L., Gruenewald, J., Roberts, P., & Damphousse, K. R. (2015). The emergence of lone wolf terrorism: Patterns of behavior and implications for intervention. In M. Deflem (Ed.), Sociology of Crime, Law and deviance (Vol. 20, pp. 89–110). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1521-613620150000020005

- Spaaij, R., & Hamm, M. S. (2015). Key issues and research agendas in lone wolf terrorism. Studies In Conflict & Terrorism, 38(3), 167–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2014.986979

- SPLC (Southern Poverty Law Center). (2022). The Year in Hate & Extremism Report 2021. Accessed May 27, 2022. https://www.splcenter.org/20220309/year-hate-extremism-report-2021

- Stevens, T., & Neumann, P. R. (2009). Countering online radicalization: A strategy for action. International Centre for the Study of Radicalization and Political Violence.

- Sunstein, C. R. (1999). The law of group polarization. John M. Olin Program in L. & Econ. Working Paper No. 91

- Suttmoeller, M. J., Chermak, S. M., & Freilich, J. D. (2018). Is more violent better? The impact of group Participation in Violence on group longevity for Far-Right extremist groups. Studies In Conflict & Terrorism, 41(5), 365–387. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2017.1290429

- The Associated Press. (2015). Don’t Blame Us for Church Shootings, Council of Conservative Citizens Says. NBC News.https://www.nbcnews.com/storyline/charleston-church-shooting/dont-blame-us-church-shootings-council-conservative-citizens-says-n380126

- Venhaus, J. M. (2010). Looking for a fight: Why youth join al-Qaeda and how to prevent it. Carlisle, PA: US Army War College.