ABSTRACT

Purpose

To explore the impact of having relatives with addiction problems on students’ health, substance use, social life, and cognitive functioning, and to establish possible contributions of the participants’ gender, type of relationship, and type of addiction of the relative(s).

Methods

A qualitative, cross-sectional study of semi-structured interviews with thirty students from a University of Applied Sciences in the Netherlands who had relatives with addiction problems.

Results

Nine major themes were identified: (1) violence; (2) death, illness, and accidents of relatives; (3) informal care; (4) perception of addiction; (5) ill health, use of alcohol and illegal drugs; (6) financial problems; (7) pressured social life; (8) affected cognitive functioning, and (9) disclosure.

Conclusions

Having relatives with addiction problems severely affected the life and health of participants. Women were more likely to be informal carers, to experience physical violence, and to choose a partner with addiction problems than men. Conversely, men more often struggled with their own substance use. Participants who did not share their experiences reported more severe health complaints. It was impossible to make comparisons based on the type of relationship or type of addiction because participants had more than one relative or addiction in the family.

Introduction

Addiction is a major problem that impacts not only the person but also family members such as (adult) children, siblings, and partners (referred to collectively as Affected Family Members (AFMs)). Having a relative with addiction problems can be very stressful. In families with addiction problems experiencing or witnessing physical, emotional, and/or sexual violence is common (Choenni et al., Citation2017; Orford et al., Citation2013; Velleman & Orford, Citation1999) and often traumatic (Van der Kolk, Citation2022). AFMs may have been neglected, their property may have been damaged, or they may have run into financial difficulties (Laslett et al., Citation2019). The subsequent strain affects AFMs’ health and family life. Children who grew up with parents with addiction problems have been found to experience various mental health problems, especially depression, and anxiety (Casswell et al., Citation2011; Velleman & Orford, Citation1999; Velleman & Templeton, Citation2016). They are also more likely to have poorer parent-child relationships (Pisinger et al., Citation2016), adopt parenting roles at a young age (Kelley et al., Citation2007), develop behavioural problems (Harwin et al., Citation2010; Kelley et al., Citation2010), and alcohol and drug problems (Feinstein et al., Citation2012; Greenfield et al., Citation2015; Houmøller et al., Citation2011).

Research into harm experienced by young adult family members focuses mainly on young adults’ own alcohol and drug problems (Rossow et al., Citation2016) and mental ill health (Kelley et al., Citation2011), although other outcomes, like educational challenges, have been studied (Lowthian, Citation2022). It is unclear whether the harm experienced by young AFMs is related to gender, family relationship (partner, mother, father, sibling, etc.), and type of addiction. One study found that children suffer more negative consequences from a mother’s addiction than from a father’s (Berends et al., Citation2014). In another study, family conflict and parental substance use problems were significantly associated with alcohol and drug problems among females, but not among males (Skeer et al., Citation2011; Straussner et al., Citation2011). Other studies show no differences in these respects (Kuppens et al., Citation2020; Oram, Citation2019; Pisinger et al., Citation2016). How AFMs are affected by a sibling’s addiction is largely unknown.

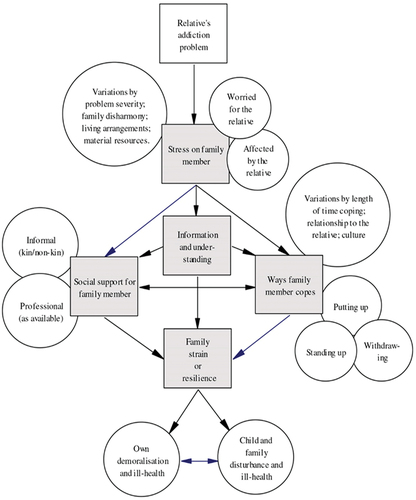

The Stress-Strain-Information-Coping-Support model (SSICS) is designed specifically to describe and explain the experiences of AFMs (shown in ) (Orford et al., Citation2010). The SSICS-model assumes that the stressful impact of a relative’s alcohol, drug, or gambling problem is a cause of strain experienced by the family member. The ways a family member copes and the support the family member receives are factors that moderate the stress-strain relationship (Orford, Templeton, et al., Citation2005). Stress is defined as (1) an active disturbance by the relative’s moodiness and aggression; (2) a disruption of family, financial, and social life and (3) concern for the relative’s health and well-being (Orford, Templeton, et al., Citation2005). Strain is defined as (1) distress and (2) psychological and physical ill health (Orford, Templeton, et al., Citation2005). Information is defined as AFMs’ understanding of what is taking place, factual information about different kinds of drugs, and the way they work. Information is also about realizing the link between the addiction problem and AFMs’ physical and mental health. The model identifies three coping mechanisms : (1) to put up with relatives’ behaviour (to accept things as they are or even accommodate the relative’s substance use), (2) to stand up (getting aggressive or trying to control their relatives’ drinking or drug taking, trying to minimize harm for other family members, supporting the relative to seek treatment), and (3) to withdraw and try to maintain independence (to take what is happening less personally, getting involved in other activities, escaping or getting away and getting a new and better life for oneself) (Orford et al., Citation2013). Support is defined as informal and professional support (Orford et al., Citation2013). The model has been used in qualitative and quantitative research in a wide variety of countries including Australia, Brazil, India, Iran, the Republic of Ireland, Italy, Mexico, New Zealand, and the UK (Ahuja et al., Citation2003; Church et al., Citation2018; Fereidouni et al., Citation2015; Orford et al., Citation2019; Orford, Natera, et al., Citation2005). Results after using this model in these countries, demonstrated its usefulness and validity. Orford et al. (Citation2013), argue that the SSICS-model is designed to be “non-pathological in its assumptions about AFMs and their thoughts, emotions, and actions in relation to their relatives with addiction problems” (p.71). With the SSICS-model, the authors oppose the concept of co-dependency, in which family members of the person with an addiction problem are seen as people suffering from an illness, enablers, and co-alcoholics (Bacon et al., Citation2020).

Figure 1. Stress-Strain-Coping-Support Model (Orford, Citation2013).

Estimates of the number of AFMs vary. Although some studies found that 3–6% of children under the age of 18 years were AFMs (Berg et al., Citation2016), other studies indicate greater figures, ranging from 9.5% (Berndt et al., Citation2017) to approximately 25% (Casswell et al., Citation2011) and 26% (Schroeder & Kelley, Citation2008). In a study with 5,662 participants enrolled in higher education in the Netherlands, 15.6% reported having one or more relatives with addiction problems (Van Namen et al., Citation2022). The high prevalence of AFMs among this group, along with evidence that the foundation for most health problems (especially mental disorders) is established in late adolescence (Richmond-Rakerd et al., Citation2021; Sawyer et al., Citation2012; Wertz et al., Citation2021), stresses the urgency to specifically address the needs of this group.

The aim of this study is therefore to explore and deepen our understanding of the impact of having relatives with addiction problems on students’ health, use of alcohol and drugs, social life, and cognitive functioning and to establish possible contributions of the participants’ gender, type of relationship to the relative, and the type of addiction. Here, we focus on the components “stress” and “strain” of the SSICS-model.

Materials and Methods

Design

A qualitative, cross-sectional study consisting of in-depth, individual semi-structured interviews with students in higher education in the Netherlands who self-identified as AFMs.

Participants and recruitment

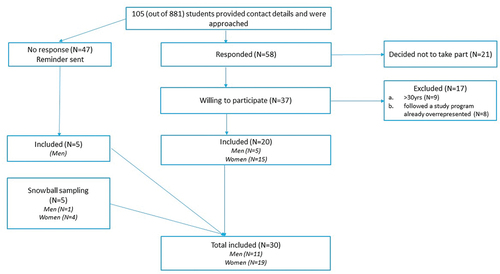

Students (18–30 years old) who responded positively to the question “Is there anyone in your family with behavioral and/or health problems due to alcohol/drugs/medications, such as painkillers, sleep medication or tranquilizers?” in an online survey at Rotterdam University of Applied Sciences (RUAS) on substance use and who provided an email address were invited by email to be interviewed. We applied purposive sampling (Etikan, Citation2016) aiming for an equal distribution of genders and ethnicity, and a diverse group based on study programme, study year, type of addiction, and relationship to relatives (shown in ). Five students were suggested by other participants and thus by snowball sampling. Students over the age of 30 were excluded because they led a different kind of life from students 18–30. They were pursuing master’s degrees, often part-time, and alongside their jobs and families. Initially, only a few men wanted to participate. To recruit more men, we altered the text in a second mailing. On the subject line (ANONYMOUS research on the addiction of family members) we added: “Would you like to participate?” In the email text, the following line was added: “I am looking for a mix of people with different experiences: severe and less severe, students who have (had) problems because of a relative’s addiction and students who have not.” It appeared that men were more likely to participate if they were not problematized in advance. This resulted in an additional five male participants. To include more participants from diverse cultural and ethnic backgrounds we used social media and tried to get in touch with these groups through colleagues from different ethnic backgrounds and culturally diverse student organizations. These attempts provided no extra participants.

Development of qualitative interview

The interviews were guided by a topic list focusing on how a relative’s addiction affected the interviewee’s health, social-economic life, and cognitive functioning. The topic list (Appendix) was based on the SSICS-model (shown in ), supplemented by items on study progress and study delay (which are not used for the current analysis).

The interviews were conducted by the same researcher (DvN), between September 2019 and February 2020, at the university premises or in a public location, according to the preference of the interviewee. The interview was face-to-face, lasted approximately 78 minutes (range 53–116), was recorded on a digital voice recorder, transcribed verbatim, and anonymized for analyses. The transcriptions were made by a student not affiliated with the universities involved, to prevent recognition of a fellow student. This student signed a declaration of confidentiality.

At the end of the interview, each participant received a verbal summary of the key findings and the researcher’s interpretation of the interview for participant-checking, allowing the participant to comment on the findings and possibly add data (Harvey, Citation2015). With this, we followed the COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research (COREQ guidelines) (Tong et al., Citation2007). COREQ recognizes participant-checking as a method of rigour: “Obtaining feedback from participants on the research findings adds validity to the researcher’s interpretations by ensuring that the participants’ meanings and perspectives are represented and not curtailed by the researchers’ agenda and knowledge” (35, p.356). If participants had indicated they wanted to see the transcript, we sent it.

Data analysis

The data were thematically analysed using Atlas.ti 8.4, with a provisional 14-item list of codes consisting of different types of stress and harms derived from the SSICS-model (Orford, Natera, et al., Citation2005). The list was continuously supplemented and deepened with new codes and insights that we identified inductively from the data. Codes were then organized in an iterative process using summary tables to generate themes reflecting the stress and strain of the participants. This resulted in 24 codes combined into nine themes (Supplementary table).

For analysis, we used the Directed Content Analysis (DCA) procedure (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005). DCA is a suitable method for qualitative analysis when a detailed theory to guide the data analysis exists, as it helps structure the data analysis while allowing new insights to emerge. DCA is a reliable, transparent, and comprehensive method that can increase the accuracy of data analysis, test theories, and compare findings from different studies (Assarroudi et al., Citation2018). Moreover, DCA makes it clear, especially as research increases in a particular area, that researchers do not work without prior knowledge, while this is often considered “the hallmark of qualitative research” (p.1283) (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005). Using theory for analysis has some inherent limitations. Researchers could be more likely to find evidence that is supportive rather than non-supportive of the theory (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005). To avoid this, two researchers coded the data.

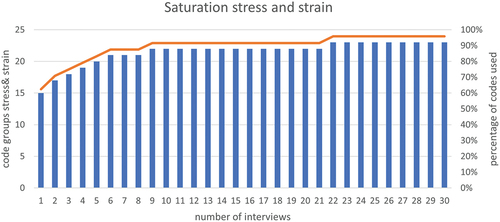

Seven steps were followed (Assarroudi et al., Citation2018). (1) Two researchers got immersed in the data (DvN, VK). (2) Before coding, a formative matrix of the main categories (Stress-Strain-Information-Coping-Support) and related subcategories (for example, Stress: aggression; substance use relative (increase, relapse, overdose); behaviour relative) was deductively derived from the existing theory and previous research (Supplementary table). (3) The main categories were defined and supplemented with examples. (4) Anchor samples for each main category were added. (5) The interviews were then coded by two researchers independently (DvN, VK). They read and reviewed the transcripts several times, and discussed the coding, the categorization matrix, and any disagreements until agreement was reached. (6) New codes, retrieved inductively from the data were added (for example, Stress: mortal danger; death relative; illness relative) (Supplementary table). (7) Codes were organized in an iterative process using summary tables. The analysis outcomes were discussed by the entire research team, after which some refinements and additions were made. This led to a final codebook with 58 codes. A saturation of 95% was reached after 22 interviews (shown in ).

Research team and reflexivity

The female interviewer (first author) is an experienced journalist who was privately acquainted with people with addiction. Her personal experiences were an important motive for doing the research. To earn trust, she told the interviewees that she had experience on the subject but did not elaborate on her experiences. The second coder (VK) had no experience with addiction in her family.

Results

Participants

Of the 30 participants, 19 (63%) were women (). Participants had a total of 107 relatives with addiction problems (mean 3.6 (SD 2.0)) in their extended families. 58 were in their nuclear families (14 fathers, 13 mothers, 1 stepmother, 6 stepfathers, 19 siblings, and 5 partners). Three had only one relative with an addiction. In almost all cases alcohol addiction was present. The majority of relatives were poly-users. Participants expressed strong motivation to participate in the study.

I think breaking the silence has enormous benefits. For yourself and society. I think that talking about this kind of suffering is good. That’s why I want to participate [P8, man, 22 yrs].

Table I. Characteristics of participants.

Results are presented in two sections (stress and strain) based on nine themes: (1) violence and aggression; (2) death, illness, and accidents of relative; (3) the burden of informal care; (4) perception of the nature of addiction; (5) ill health including addiction; (6) financial problems; (7) pressured social life; (8) affected cognitive functioning, and (9) disclosure.

Stress: violence and aggression

Participants described highly stressful events of experiencing or witnessing physical, emotional, and/or sexual violence (). Eight of them had ever been in mortal danger.

He [partner] was completely lost. Then suddenly he grabbed his sheet, pulled it around my neck, and started to strangle me [P6, woman, 23 yrs].

Table II. Experienced and witnessed violence by participants.

Emotional violence was common. Half of the participants, mostly women, experienced physical violence. Physical violence was always accompanied by emotional violence, with emotional violence often having more impact.

He [stepfather] liked to put cigarette butts on my arm. It hurt a lot for one minute and after that, he didn’t bother me for a whole evening. Still, I preferred that above some of the things they [stepfather and mother] said to me, like: “I would rather not have had you” [P10, woman, 24 yrs].

Several participants had been shut out of the house.

I was locked out at minus twelve because I had thrown away the wine. I never told anyone, because I was afraid that Child Protective Services would come for my little brother [P18, woman, 26 yrs].

A few participants mentioned sexual violence, but not by the relative.

“My teenage years were not good and sometimes dangerous. There were men who took advantage of me and my situation. Men in their thirties and I was just fifteen. I think I was looking for a stable factor, a parent figure” [P26, woman, 26 yrs].

Participants also perceived these experiences as a result of not being able to put boundaries.

In terms of sex, I didn’t know what I wanted or didn’t want. I was still very young. I had to learn to set my limits [P11, woman, 24 yrs].

Some participants had been bullied at secondary school. They related this to addiction problems in their family.

I was mature as a child because you’ve been through so much. Then you don’t match with your classmates. I didn’t have the nicest clothes either, because I wasn’t taken care of, so I was also bullied at school that period. So then I went truant because I didn’t want to go to school [P15, woman, 23 yrs].

Stress: death, illness, and accidents of the relative

Three participants lost a parent or brother to the consequences of addiction problems and related psychiatric problems. The circumstances were traumatic for those who were left behind, for example when the relative was found by the family member or when the police came to the house to break the news.

I was still in my pajamas watching Netflix on the sofa and the police rang the doorbell. So I said: “Okay, there’s something with my mother, there’s something with my father or I have to go to the police station for a fine I haven’t paid, but I paid it last week, so it can’t be that.” Such things were going through my head. But they said: “No, we’re not allowed to say it until you sit down.” I walked to the living room and sat down in the corner of the sofa. One came and sat next to me and the other sat on that chair. And then they said: “We have bad news.” And I said: “What is it?” And yes, then they told me that my mother was dead [P10, woman, 24 yrs].

One participant had to decide to stop the treatment of the physical problems of a relative with Korsakov, after which the relative died. In addition, many of the participants reported illness of a relative (such as Korsakov) and severe falls (from stairs/platform; in the house; on the street; in water).

My father fell into a canal drunk a couple of times and couldn’t get out by himself. That could have ended very differently [P29, man, 21 yrs].

A few relatives had car accidents or attempted suicide. Serious health problems arose during periods of withdrawal. Then, underlying psychological problems also emerged.

When my brother tried to quit blowing, he suffered a depressive episode. With him, fortunately, it wasn’t as bad as with my father, who kept threatening to kill himself. I think my father’s depression is also why he [father] started drinking. My brother’s behaviour evoked unpleasant memories of my father [P13, woman, 22 yrs].

Stress: the burden of informal care

Some of the participants were neglected in their childhood. The household was neglected, meals were not made every day, and were often not healthy. Their clothes were outdated or not clean. Some participants—especially daughters of mothers with addiction problems—adopted parenting roles at an early age. They took care of the household, cleaned up after falls of the relative, took care of siblings, and maintained contact with the rest of the family or with social services/doctors. Providing support to relatives with addiction problems brought positive feelings to a few participants, but most of them felt exhausted, especially when there was no one to help them.

I also shopped for groceries and did things at very strange times: vacuuming in the morning at six o’clock to make sure mom didn’t wake up, then she wouldn’t get angry. Laundry washing at four in the afternoon, she wouldn’t get angry then. At some point, it became much too heavy for me [P18, woman, 26 yrs].

Stress: perception of addiction

Some participants reacted with frustration when addiction was called a disease.

It is not a disease. It does not happen to him, he does it to himself. He certainly is not fighting it [P6, woman, 23 yrs].

These participants concluded they were not important enough for their relatives to seek help.

My mother went to a clinic when she fell ill. I thought: Why do you seek help when it comes to your health and not for us? At the clinic, we also talked about it: Why not for us? And then a counselor said: “Alcoholism is a disease that takes over your whole life, and all your thoughts, and all your choices.” So we were like: yeah okay, so, that means we are not…She was more afraid of dying than of losing us [P30, woman, 21 yrs].

Other participants found comfort in seeing addiction as a disease.

I want to see it as an illness, then I can accept it better [P3, woman, 23 yrs].

Strain: Ill health, including addiction problems, of the participants

Almost all participants mentioned mental health problems (). Some reported substance use problems of their own. A majority reported physical complaints related to chronic stress, such as migraine, and chronic back or neck pain. Some of the young women reported that their periods had ceased; several had eating disorders. Most mentioned periods of chronic fatigue and sleeping problems.

Table III. Health problems and diagnoses of participants.

Most participants expressed strong feelings of depression, devaluation, resentfulness, shame, guilt, disappointment, and frustration at the time of the interview. Some suffered from anxiety. Several participants reported self-harm, suicide ideation, and suicide attempts. For most, but not for all, these behaviours were a thing of the past. Sometimes self-harm continued in periods of high stress.

I am quite competitive, also in cutting behaviour. For example, if I see on Instagram that someone cuts deeper than me, I have to do the same. That’s not good. It’s about having control. Deciding for yourself how far you go and then doing it the way you imagined [P16, woman, 22 yrs].

One-third of the participants had been diagnosed by a general practitioner or psychologist with a psychiatric disorder, of which PTSD (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder) was the most frequent. The diagnoses tended to change over time. Especially Borderline Personality Disorder was a diagnosis that came and went.

At the end of the study year, I had a burnout. I was collapsing because of the situation at home. So I am now back in therapy. First I was diagnosed with ADHD and Borderline. I had therapy for that but now, Borderline has been removed from the medical record. And then they diagnosed OCPS, Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Syndrome, which is probably overcompensation for chaos. I want regularity, structure, clarity [P2, woman, 23 yrs].

Most participants reported that they had no problems with the labels they were given, as their diagnosis paved the way for help.

The psychologist said I had PTSD and a developmental disorder. I was happy to get a label because I was fretting: “What is wrong with me? Am I depressed? I sleep badly, have nightmares, do I have PTSD?” I thought a developmental disorder was the correct term. If I kept feeling like that, then I wouldn’t develop well, then, yeah, it wouldn’t turn out well, I think [P14, man, 24 yrs].

When asked if participants also saw positive aspects to their relative’s addiction, almost all said that their relative’s addiction acted as a warning to them, which made them confident that they would be less likely to develop addiction problems themselves. However, some struggled with their own substance use, some mentioned their own use as worrisome or problematic at times, and a few called themselves addicted. Men reported more substance use problems than women. One participant had been admitted to a clinic for addiction management.

I was voluntarily admitted to an addiction clinic for ten weeks. I am now two and a half years clean. I broke off contact with my father because I know how quickly I am triggered by comments from him. I take over his behaviour so easily. I still have no contact with him because I know he is still using [P8, man, 22 yrs].

Most participants used alcohol and/or drugs on a weekly or daily basis. A minority of the participants used little or no alcohol or drugs themselves.

Because of my father, I have an aversion to alcohol. I’ve never been drunk either. I need control. I do have a beer sometimes, but then it’s just one beer. If I feel anything at all, I stop [P16, woman, 22 yrs].

Many participants had physical health problems.

I had palpitations. My heart was just, yes, racing, because of the stress [P9, man, 24 yrs].

Many participants reported sleeping problems.

At least once a week I dream that I see my family swim. They all drown and I’m the only one left. A terrible dream [P19, woman, 27 yrs].

Not all participants reported health complaints. The ones who did not face violence, or faced little violence, were better off.

Strain: financial problems of the participants

Although most participants grew up in a middle or upper-class family, many experienced conflicts or worries about the financial situation of the relative with addiction or the household. Unemployment, drug dealing, and increasing debts of their relatives were frequently mentioned. Siblings with addiction problems being homeless, or going to the food bank were mentioned a few times. Sometimes creditors came to the door. A few participants felt pressured to give or lend money to the relative or contributed financially from an early age to keep the household running.

My father became unemployed and then we were almost evicted from our house. And sometimes my parents borrowed money from me, because I always had side jobs, from the age of 11. 100 euros for groceries or so. Now my father works again and is slowly paying off debts. But sometimes he spends a lot, obsessively buying stuff [P1, woman, 19 yrs].

A few participants responded by becoming extremely frugal or thrifty.

I lived on bread and cucumber because everything else was too expensive, I thought. Whereas, I had more than enough money. But the idea of spending it… That’s where I see the most effect [P3, woman, 23 yrs].

Strain: pressured social life of the participants

A vast majority of the participants reported disrupted relationships with their relatives with addiction problems. Regularly, the addiction problems disrupted the relationships with other family members as well. Most participants were satisfied with their social life outside the family.

Many relatives showed negative behaviour. They were aggressive, insulted or humiliated participants, did not take responsibility for themselves or others, or blamed and rejected others. Some participants broke off or limited contact with their relatives.

I still have contact with my father, but I keep it businesslike. If I need something I call him, if he needs something he calls me. It is not friendly or something. As businesslike as possible [P7, man, 22 yrs].

Some relatives showed manipulative or victim behaviour. Other relatives showed socially inappropriate behaviour such as falling asleep at unusual moments and places, behaving as if helpless, or did not keep appointments. Some had forgotten important events.

My mom couldn’t remember why as a child I was in the hospital so often [P15, woman, 23 yrs].

Witnessing the sadness or despair of other family members, particularly a parent or younger sibling, could also create—or worsen—a disruption in the relationship between the participant and the relative.

What I blamed my brother for was not for myself but for my father. There was a time when I no longer saw my brother as a brother, but as a [swear word] who broke my father’s heart [P2, woman, 23 yrs].

Still, most participants stated explicitly that they still loved their relatives.

Alcoholism and the person who is addicted to alcohol are not the same. My mom is a very sweet woman. She’s just not nice when she’s been drinking. Nobody is only an alcoholic. She’s also a person you love [P30, woman, 21 yrs].

Sometimes the conflicts with the relative improved the bond with other family members, especially siblings, but usually, this was not the case and the addiction problems disrupted the relationships with other family members or people in their environment as well. Some participants were annoyed with the way other family members dealt with the addiction problems or closed themselves off to everyone. Regularly the relative with addiction problems tried to set up family members against each other.

When my stepmother was drunk, she often talked badly about my mother or she told me things about my sister that I didn’t want to know [P20, man, 23 yrs].

Most participants were satisfied with their social life outside the family. They had friends, good relations with other students, a side job, or played sports.

I think it helps that I have a lot of friends. And I’m a talker, I talk it off easily [P23, woman, 23 yrs].

Several participants brought no or very few friends home when they still lived with the relative. A few reported they had few or no friends.

I no longer value relationships. I’m not close with anyone [P22, woman, 25 yrs].

Strain: affected cognitive functioning

Some participants experienced cognitive problems: difficulty concentrating or memory problems.

Because of that trauma, you forget things. Well, you don’t forget things, but you don’t get to them as easily [P15, woman, 23 yrs].

Some felt an extreme urge to prove themselves.

I cannot be satisfied with an A. I should have an A plus .That’s terrible [P22, woman, 25 yrs].

Some doubted their perception of events, or experienced knowledge gaps.

I didn’t know that you have to walk on the right side of the street or a (rolling) staircase. No one ever taught me that. […] There are many things about everyday life that I don’t know [P9, man, 24 yrs].

Disclosure by the participants

Some participants did not tell anyone what they were going through, others told one friend or only talked about it with siblings. If the subject was open to discussion within the family, it usually did not bring relief.

It causes arguments, we can’t get our words across or we don’t accept each other’s words. And the problem with my girlfriend is that she has not been through enough in life to be able to talk about it [P25, man, 21 yrs].

For others, the relative’s addiction problems could not be discussed within the family at all, but they could talk to in-laws, a friend’s parents, a psychologist, or a teacher.

In our family, we don’t talk about it, it is some kind of taboo or something. But with my girlfriend, her parents, and my friends, luckily, I can talk about it [P29, man, 21 yrs].

A few participants discussed their depressive symptoms or problems with their own substance use within or outside the family but did not disclose the addiction problems of a relative. In about half of the cases, the addiction problems of one or more relatives were discussed quite openly, but it had taken a long time before the taboo on talking about it had disappeared. Problems were hardly ever discussed with the relative with addiction problems.

For those who never talked to others about their experiences—professionals, family, or friends—life seemed the hardest because they reported more severe complaints. For them, the interview was the first time they disclosed their family history. They were relieved—although sometimes very emotional—that they had been able to talk about it and that their experiences were taken seriously. The fact that the interviewer was an expert by experience provided relaxation and less embarrassment.

It’s nice to talk about it with someone who has been through it and also knows about it. It’s quite a revelation [P25, man, 21 yrs].

Gender, relationship, number, and type of addiction problems

We found some differences between men and women. Participating men seemed to struggle more with their own substance use than women. Participating women more often experienced physical violence, had more informal care responsibilities, and were more likely to have partners with addiction problems than men. In general, women spoke more freely about their experiences, while men were more reserved. After a divorce, mothers with addiction problems seemed more likely to choose a new partner with addiction problems than fathers. Therefore, participants with mothers with addiction problems were more likely to have both a mother and a stepfather with addiction problems.

All kinds of addictions could be encountered in one family, as the participants had on average 3.6 relatives with addiction problems. Most of the relatives were poly-users. For this reason, it was impossible to unravel the influences of the relationship to relatives or the type of addiction. The addiction problems of relatives in the nuclear family (average of 1.9) weighed more heavily on the participants than relatives in the extended family.

There is always someone with whom things are not going well. If my brother is doing better, my brother-in-law is doing worse. But I must say that I find my brother’s use much more difficult to deal with than my brother-in-law’s [P25, man, 21 yrs].

Having more than one relative with addiction problems contributed to a feeling of not being able to escape the problems. A participant stated:

If my mother is drunk, I leave. Sometimes it happens that, when I get home, my grandmother calls. Also drunk. That feeling, that I cannot escape it, that’s hard [P19, woman, 27 yrs].

Discussion

The goal of this study was to explore the impact of having relatives with addiction problems on students’ health, substance use, social life, and cognitive functioning, and to establish possible contributions of the participants’ gender, type of relationship, and type of addiction of the relative(s).

First, an important finding of our study was that a vast majority of the participants reported generally high levels of stress and strain because of having relatives with addiction. Still, participants were pursuing higher education and were successful enough to be able to study at a university. It, therefore, is possible (maybe likely) that stress and strain might be even greater in those who dropped out of college or were not able to even get to college in the first place. Stress and strain symptoms—ill health, and affected social and cognitive functioning—are also mentioned in other studies (Orford et al., Citation2013; Velleman & Templeton, Citation2016). Perception of the nature of addiction as a stress factor—Is addiction a disease and if so, why does a relative not want to be treated?—has not been described before.

Second, many participants found it difficult to discuss their family situation. We found that non-disclosure was associated with more severe health problems. The limited research on the disclosure of AFMs examined the process of disclosure to and support gained from friends in childhood (Cormier, Citation2014) or the differences in self-disclosure between AFMs and no AFMs (Bradley & Schneider, Citation1990), but not the relationship with ill health.

Third, often mentioned by participants was the violence they encountered when confronted with parents, siblings, or partners when using alcohol or drugs. Some of the participants had even been in mortal danger. In this study, a few participants experienced partner violence, but most experienced or witnessed violence by parents, some by siblings. Ample research has been done on domestic violence in families with addiction problems (Choenni et al., Citation2017; Velleman et al., Citation2008), but this is mainly quantitative research (Arai et al., Citation2021). There is much less qualitative research on young people’s experiences with domestic violence, while this kind of research provides understanding and description of personal experiences of complex phenomena (Banyard & Miller, Citation1998) as well as additional insights into the variation of experiences (Johnson & Onwuegbuzie, Citation2004). In our study, we let the voices of students who are experiencing or have experienced domestic violence be heard. Our participants reported emotional violence most often, followed by physical and sexual abuse. Parental emotional violence is a risk factor for more severe PTSD symptoms in children and adolescents (Hoeboer et al., Citation2021) and is more strongly associated with depression and anger than parental physical violence (Teicher et al., Citation2006). Many participants in our study experienced multiple forms of violence. Exposure to multiple types of violence (physical, emotional, sexual) is associated with very large effect sizes on psychiatric symptoms, including an increased risk of suicide (attempts) (Teicher et al., Citation2006; Ting et al., Citation2022). Most studies on violence in relation to addiction have focused on intimate partner violence and child maltreatment (Choenni et al., Citation2017; Velleman et al., Citation2008). As far as we know only a few studies addressed violence by siblings with addiction problems (Jackson et al., Citation2007).

Fourth, another important finding was that most participants had more than one relative with addiction problems. Velleman & Templeton (Citation2016) showed that risks are greater if a child lives with two parents with addiction problems. Quantitative research among the same population as in the current study showed that students with more than one relative with problematic substance use had significantly worse physical and mental health, felt less calm and peaceful, and were more likely to be downhearted and blue than were students with one relative with problematic substance use (Van Namen et al., Citation2022).

Fifth, in the present study, not many of the participants did express worry about their relatives, whereas in the existing literature on AFMs worrying about the relative is the most common stress factor (Orford et al., Citation2013; Orford, Natera, et al., Citation2005). Future research could explore whether this difference is a matter of culture, age, or type of relationship. Still, the participants in our study did worry about other family members, especially younger siblings.

Recommendations

Many participants mentioned finding it difficult to discuss the problems they had encountered. Because non-disclosure was associated with more severe health problems, we recommend facilitating the training of study coaches on the topic of addiction problems in the family, to enable talking about these experiences. Although teaching packages on alcohol and drugs are available for all levels of education (Trimbos-instituut, Citation2021), information about the impact on the family is not included but can easily be added. Increasing awareness of these problems can help identify those at risk for health problems much earlier in life, which may prevent ill health at a later age.

Study strengths and limitations

This study contributes to a better understanding of the stress and strain that students with relatives with addiction problems may experience. Participants were all in higher education, and hence the results are not generalizable to other populations. This study might be prone to selection bias because the students selected themselves. Also, they were predominantly of Dutch ethnic origin, while the student population is more diverse. In the Netherlands, the percentage of students with a non-Western migration background is 17.3% (Ministry of Education, Citation2021). Attempts to include participants from other cultural and ethnic backgrounds failed.

Conclusions

Participants experienced a lot of violence, notably emotional violence. They were at high risk for physical and especially mental ill health, including suicide ideation, self-harm, and risky use of alcohol and illegal drugs. Depression, loss of self-worth, and PTSD were prevalent. Moreover, most experienced a combination of ill health, financial problems, pressured social life, and affected cognitive functioning as a result of their relatives’ addiction. Participants who had not previously shared their experiences reported more severe health complaints. Participants who did not experience violence reported less severe health complaints.

The average number of relatives with addiction problems was high, as well as the number of types of addiction (alcohol, drugs, gambling, other, and in various combinations) that relatives suffered from. This contributed to a feeling of not being able to escape the problems. We found some differences between men and women. Men seemed to struggle more with their own use of alcohol and drugs than women, while women experienced more physical violence, more often had informal care duties, and were more likely to have partners with addiction problems than men. Raising awareness through education of the experiences and health risks of students with family members with addiction problems might help identify people at risk for mental ill health much earlier in life, and prevent ill health at an older age.

Statement of ethics

This study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Faculty of Health, Medicine, and Life Sciences Research Ethics Committee of Maastricht University (approval number FHML-REC/2020/094). Participants were assured of confidentiality and informed (verbally and in writing) about the goal of the research and the procedures (voluntary participation, anonymity). All thirty participants provided written informed consent. Data were processed anonymously.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (17 KB)Acknowledgments

We deeply thank the thirty young people who participated in our research for their trust and the openness with which they spoke about their stressful and often difficult family circumstances and the impact it had on them.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study (interview transcripts) are not publicly available because they contain information that could compromise the privacy of research participants but are available from the corresponding author [DvN] upon reasonable request.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2023.2223864.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Dorine M. van Namen

Dorine van Namen worked as a journalist for most of her working life. In 2020, she began her PhD research, which focuses on the impact of having relatives with addiction problems on the health and life of young adult family members.

Vera Knapen

Vera Knapen is a junior researcher in the field of health education and promotion.

AnneLoes van Staa

AnneLoes van Staa is professor Transitions in Care at Rotterdam University of Applied Sciences. Her research focus is on patients’ lived experiences with chronic illness, patient participation in care, self-management support by professionals, and the vitality and health of healthcare professionals and students. In 2019, she was awarded the first Dutch Delta Award, a national prize of €500K for her excellence in combining applied research, practice improvement, and professional education.

Hein de Vries

Hein de Vries is a professor in health communication at Maastricht University. His research focuses on understanding factors related to health behaviors and health policies using and testing the I-Change Model, and developing and implementing evidence-based health promoting interventions, such as school-based programs, health counseling protocols, and computer tailored eHealth.

Sander R. Hilberink

Sander Hilberink is a professor ‘Ageing with lifelong disabilities’ at Rotterdam University of Applied Sciences. He published on smoking cessation support for COPD patients in general practice, alcohol, benzodiazepines, and nicotine dependence.

Gera E. Nagelhout

Gera E. Nagelhout is Chief Science Officer of IVO Research Institute in The Hague and Endowed Professor at the Department of Health Promotion of Maastricht University in the Netherlands. Her research focuses on health, well-being, and addiction among people of lower socioeconomic status.

References

- Ahuja, A., Orford, J., & Copello, A. (2003). Understanding how families cope with alcohol problems in the UK West Midlands Sikh Community. Contemporary Drug Problems, 30(4), 839–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/009145090303000406

- Arai, L., Shaw, A., Feder, G., Howarth, E., MacMillan, H., Moore, T. H. M., Stanley, N., & Gregory, A. (2021). Hope, agency, and the lived experience of violence: A qualitative systematic review of children’s perspectives on domestic violence and abuse. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 22(3), 427–438. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838019849582

- Assarroudi, A., Heshmati Nabavi, F., Armat, M. R., Ebadi, A., & Vaismoradi, M. (2018). Directed qualitative content analysis: The description and elaboration of its underpinning methods and data analysis process. Journal of Research in Nursing: JRN, 23(1), 42–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744987117741667

- Bacon, I., McKay, E., Reynolds, F., & McIntyre, A. (2020). The lived experience of codependency: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 18(3), 754–771. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-9983-8

- Banyard, V. L., & Miller, K. E. (1998). The powerful potential of qualitative research for community psychology. American Journal of Community Psychology, 26(4), 485–505. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022136821013

- Berends, L., Ferris, J., & Laslett, A.-M. (2014). On the nature of harms reported by those identifying a problematic drinker in the family, an exploratory study. Journal of Family Violence, 29(2), 197–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-013-9570-5

- Berg, L., Bäck, K., Vinnerljung, B., & Hjern, A. (2016). Parental alcohol-related disorders and school performance in 16-year-olds-a Swedish national cohort study. Addiction, 111(10), 1795–1803. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13454

- Berndt, J., Bischof, A., Besser, B., Rumpf, H.-J., Bischof, G. (2017). Abschlussbericht Belastungen und Perspektiven Angehöriger Suchtkranker: Ein multi-modaler Ansatz (BEPAS) [Internet]. Lübeck. https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/service/publikationen/details/belastungen-und-perspektiven-angehoeriger-suchtkranker-ein-multimodaler-ansatz-bepas.html

- Bradley, L., & Schneider, H. (1990). Interpersonal trust, self-disclosure and control in adult children of alcoholics. Psychological Reports, 67(3), 731–737. https://doi.org/10.2466/PR0.67.7.731-737

- Casswell, S., You, R. Q., & Huckle, T. (2011). Alcohol’s harm to others: Reduced wellbeing and health status for those with heavy drinkers in their lives. Addiction, 106(6), 1087–1094. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03361.x

- Choenni, V., Hammink, A., & van de Mheen, D. (2017). Association between substance use and the perpetration of family violence in industrialized countries: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 18(1), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838015589253

- Church, S., Bhatia, U., Velleman, R., Velleman, G., Orford, J., Rane, A., & Nadkarni, A. (2018). Coping strategies and support structures of addiction affected families: A qualitative study from Goa, India. Families, Systems, & Health, 36(2), 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1037/fsh0000339

- Cormier, E. B. (2014). How do we do no harm?: Exploring adult children of alcoholics’’ perspectives on disclosure and support from childhood peers” [Internet]. https://scholarworks.smith.edu/theses/755

- Etikan, I. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11

- Feinstein, E. C., Richter, L., & Foster, S. E. (2012). Addressing the critical health problem of adolescent substance use through health care, research, and public policy. Journal of Adolescent Health, 50(5), 431–436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.12.033

- Fereidouni, Z., Joolaee, S., Fatemi, N. S., Mirlashari, J., Meshkibaf, M. H., & Orford, J. (2015). What is it like to be the wife of an addicted man in Iran? A qualitative study. Addiction Research & Theory, 23(2), 99–107. https://doi.org/10.3109/16066359.2014.943199

- Greenfield, T. K., Karriker-Jaffe, K. J., Kaplan, L. M., Kerr, W. C., & Wilsnack, S. C. (2015). Trends in alcohol’s harms to others (AHTO) and Co-occurrence of family-related AHTO: The four US national alcohol surveys, 2000–2015. Substance Abuse: Research and Treatment, 9, 23–31. https://doi.org/10.4137/SART.S23505

- Harvey, L. (2015). Beyond member-checking: A dialogic approach to the research interview. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 38(1), 23–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743727X.2014.914487

- Harwin, J., Madge, N., Heath, S. 2010. Children affected by parental alcohol problems (ChApaps) [Internet]. https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/13863/1/2010report-on-the-research-policy-practice-and-service-development-relating-to-chapaps-across-europe1%5B1%5D.pdf

- Hoeboer, C., de Roos, C., van Son GE, Spinhoven, P., Elzinga, B., & van Son, G. E. (2021). The effect of parental emotional abuse on the severity and treatment of PTSD symptoms in children and adolescents. Child Abuse and Neglect, 111(March), 104775. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104775

- Houmøller, K., Bernays, S., Rhodes, T., Wilson, S. (2011). Juggling Harms; Coping with parental substance misuse [Internet]. https://www.ucviden.dk/ws/portalfiles/portal/102984148/juggling_harms_2011.pdf

- Hsieh, H., & Shannon, S. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

- Jackson, D., Usher, K., & O’Brien, L. (2007). Fractured families: Parental perspectives of the effects of adolescent drug abuse on family life. Contemporary Nurse, 23(2), 321–330. https://doi.org/10.5172/conu.2006.23.2.321

- Johnson, R. B., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2004). Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. Educational Researcher, 33(7), 14–26. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X033007014

- Kelley, M., Braitman, A., Henson, J., Schroeder, V., Ladage, J., & Gumienny, L. (2010). Relationships among depressive mood symptoms and parent and peer relations in collegiate children of alcoholics. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 80(2), 204–212. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01024.x

- Kelley, M., French, A., Bountress, K., Keefe, H., Schroeder, V., Steer, K., Fals-Stewart, W., & Gumienny, L. (2007). Parentification and family responsibility in the family of origin of adult children of alcoholics. Addictive Behaviors, 32(4), 675–685. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.010

- Kelley, M. L., Pearson, M. R., Trinh, S., Klostermann, K., & Krakowski, K. (2011). Maternal and paternal alcoholism and depressive mood in college students: Parental relationships as mediators of ACOA-depressive mood link. Addictive Behaviors, 37(7), 700–706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.01.028

- Kuppens, S., Moore, S. C., Gross, V., Lowthian, E., & Siddaway, A. P. (2020). The enduring effects of parental alcohol, tobacco, and drug use on child well-being: A multilevel meta-analysis. Development & Psychopathology, 32(2), 765–778. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579419000749

- Laslett, A.-M., Room, R., Waleewong, O., Stanesby, O., Callinan, S. (2019). Harm to others from drinking: Patterns in nine societies [Internet]. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241515368

- Lowthian, E. (2022). The secondary harms of parental substance use on children’s educational outcomes: A review. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 15(3), 511–522. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-021-00433-2

- Ministry of Education. (2021, April 4). Onderwijs in cijfers (Education in figures) [Internet]. https://www.onderwijsincijfers.nl/kengetallen/hbo/studenten-hbo/aantallen-ingeschrevenen-hbo

- Oram, S. (2019). Child maltreatment and mental health. The Lancet Psychiatry, 6(11), 881–882. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30370-0

- Orford, J., Copello, A., Velleman, R., & Templeton, L. (2010). Family members affected by a close relative’s addiction: The stress-strain-coping-support model. Drugs: Education, Prevention & Policy, 17(sup1), 36–43. https://doi.org/10.3109/09687637.2010.514801

- Orford, J., de FR, P. M., Canfield, M., Sakiyama, H. M. T., Laranjeira, R., & Mitsuhiro, S. S. (2019). The burden experienced by Brazilian family members affected by their relatives’ alcohol or drug misuse. Drugs: Education, Prevention & Policy, 26(2), 157–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687637.2017.1393500

- Orford, J., Natera, G., Copello, A., Atkinson, C., Mora, J., Velleman, R., Crundall, I., Tiburcio, M., Templeton, L., & Walley, G. (2005). Coping with alcohol and drug problems: The experiences of family members in three contrasting cultures. Routledge.

- Orford, J., Templeton, L., Velleman, R., & Copello, A. (2005). Family members of relatives with alcohol, drug and gambling problems: A set of standardized questionnaires for assessing stress, coping and strain. Addiction, 100(11), 1611–1624. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01178.x

- Orford, J., Velleman, R., Natera, G., Templeton, L., & Copello, A. (2013). Addiction in the family is a major but neglected contributor to the global burden of adult ill-health. Social Science & Medicine, 78, 70–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.11.036

- Pisinger, V. S. C., Bloomfield, K., & Tolstrup, J. S. (2016). Perceived parental alcohol problems, internalizing problems and impaired parent — child relationships among 71 988 young people in Denmark. Addiction, 111(11), 1966–1974. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13508

- Richmond-Rakerd, L. S., D’Souza, S., Milne, B. J., Caspi, A., & Moffitt, T. E. (2021). Longitudinal associations of mental disorders with physical diseases and mortality among 2.3 million New Zealand citizens. JAMA Network Open, 4(1), e2033448. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.33448

- Rossow, I., Felix, L., Keating, P., & McCambridge, J. (2016). Parental drinking and adverse outcomes in children: A scoping review of cohort studies. Drug & Alcohol Review, 35(4), 397–405. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12319

- Sawyer, S. M., Afifi, R. A., Bearinger, L. H., Blakemore, S. J., Dick, B., Ezeh, A. C., & Patton, G. C. (2012). Adolescence: A foundation for future health. Lancet, 379(9826), 1630–1640. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60072-5

- Schroeder, V. M., & Kelley, M. L. (2008). The influence of family factors on the executive functioning of adult children of alcoholics in college. Family Relations, 57(3), 404–414. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2008.00509.x

- Skeer, M. R., McCormick, M. C., Normand, S. L. T., Mimiaga, M. J., Buka, S. L., & Gilman, S. E. (2011). Gender differences in the association between family conflict and adolescent substance use disorders. Journal of Adolescent Health, 49(2), 187–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.12.003

- Straussner, S. L. A., Fewell, C. H., Straussner, S. L. A., & Fewell, C. H. (2011). Children of substance-abusing parents: Dynamics and treatment. Springer Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.1891/9780826165084

- Teicher, M. H., Samson, J. A., Polcari, A., & McGreenery, C. E. (2006). Sticks, stones, and hurtful words: Relative effects of various forms of childhood maltreatment. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 163(6), 993–1000. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.2006.163.6.993

- Ting, S. K., Siau, C. S., Fariduddin, M. N., Fitriana, M., Kam Fong Lee, A., Yahya, N., & Ibrahim, N. (2022). Childhood, adulthood, and cumulative interpersonal violence as determinants of suicide risk among University students. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 31(2), 167–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2021.1984352

- Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

- Trimbos-instituut. (2021, March 30). Helder op School: Hèt preventieprogramma over roken, alcohol, drugs en gamen (Clean at school: The prevention programme for smoking, alcohol, drugs and gaming) [Internet]. https://www.trimbos.nl/aanbod/helder-op-school

- Van der Kolk, B. (2022). Posttraumatic stress disorder and the nature of trauma. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 2(1), 7–22. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2000.2.1/bvdkolk

- Van Namen, D., Hilberink, S., De Vries, H., Van Staa, A., & Nagelhout, G. (2022). Students with and without relatives with addiction problems: Do they differ in health, substance use and study success? International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-022-00881-3

- Velleman, R., & Orford, J. (1999). Risk and resilience: Adults who were the children of problem drinkers. Routledge.

- Velleman, R., & Templeton, L. (2016). Impact of parents’ substance misuse on children: An update. BJPsych Advances, 22(2), 108–117. https://doi.org/10.1192/apt.bp.114.014449

- Velleman, R., Templeton, L., Reuber, D., Klein, M., & Moesgen, D. (2008). Domestic abuse experienced by young people living in families with alcohol problems: Results from a cross-European study. Child Abuse Review, 17(6), 387–409. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.1047

- Wertz, J., Caspi, A., Ambler, A., Broadbent, J., Hancox, R. J., Harrington, H., Hogan, S., Houts, R., Leung, J., Poulton, R., Purdy, S., Ramrakha, S., Jee, L., Rasmussen, H., Richmond-rakerd, L., Thorne, P., Wilson, G., & Moffitt, T. (2021). Association of history of psychopathology with accelerated aging at midlife. JAMA Psychiatry, 78(5), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.4626