Abstract

Purpose

This study explores experiences of using beach assistive technology (AT), such as beach wheelchairs, powered wheelchairs, prosthetics and crutches, to participate in sandy beach-based leisure for people with mobility limitations.

Methods

Online semi-structured interviews were conducted with 14 people, with mobility limitations and experience of using Beach AT. A phenomenological interpretative hermeneutic approach guided reflexive thematic analysis of verbatim transcripts.

Findings

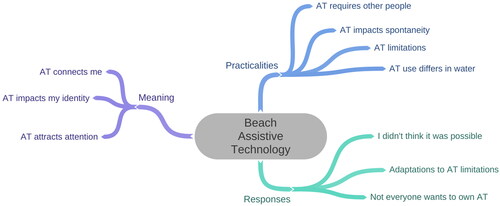

Three overarching themes were identified as: The meaning of using Beach AT, Practicalities of using Beach AT and Responses to using Beach AT. Each overarching theme was underpinned by subthemes. Meaning included: AT connects me, AT impacts my identity and AT attracts attention. Practicalities included: using AT requires other people, AT impacts spontaneity, AT limitations and AT use differs in water. Responses to using Beach AT included: I didn’t think it was possible, adaptions to AT limitations and not everyone wants to own Beach AT.

Conclusion

This study illustrates the use of Beach AT as a facilitator for beach leisure, enabling connections to social groups and contributing to one’s identity as a beachgoer. Access to Beach AT is meaningful and may be made possible through personal Beach AT ownership or access to loaned AT. The unique nature of sand, water, and salt environments requires users to identify how they plan to use the devices, with realistic expectations that the Beach AT may not enable full independence. The study acknowledges the challenges related to size, storage, and propulsion, but emphasizes that these can be overcome through ingenuity.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

People with mobility limitations require Beach assistive technology (AT) to facilitate beach leisure, social participation and to establish their identity as beachgoers.

People with mobility limitations who plan to use Beach AT should be prepared to overcome pragmatic challenges related to size, storage, and propulsion, and should have realistic expectations about the level of independence that can be achieved.

Successful use of Beach AT may involve ingenuity through adaptations such as selecting appropriate times for beach activities as well as making physical adjustments to AT devices.

Access to Beach AT is an important consideration for improving participation in leisure activities for people with mobility limitations. This is possible through both personal ownership and/or loaning AT.

Introduction

Beaches provide a setting for a multitude of leisure activities ranging from swimming, surfing, walking, and fishing to sandcastle building, and contemplation. Assistive technologies (AT) such as beach wheelchairs, beach walkers or crutches can be used by people with mobility impairments to overcome difficulties accessing these sand and tidal environments.

Where “green space” has been used broadly as a term to describe outdoors natural environments in the context of salutogenesis, “blue space” is a term to describe outdoor natural environments in, on, or around, bodies of water such as oceans, lakes, or rivers. Beaches are inherently subsumed within the concept of blue space. A systematic review of 50 papers reported benefits of blue space, including increased physical activity, restoration, and social interaction [Citation1]. This meta-analysis showed a statistically significant association between increased physical activities and restoration the closer people lived to blue space. There is also emerging evidence the use of blue spaces as therapeutic intervention [Citation2].

The fact that blue spaces offer recreational, restorative, and therapeutic benefits means that they should be easily accessed by all, including people with physical disabilities. For people with physical disabilities, specifically mobility impairments, this may require the use of AT to access sandy beaches. However, understanding the use of blue space for people with disabilities is complex as reflected by Job et al. [Citation3] who propose integrating a model for blue space health and the ICF physical health and disability model, culminating in the “BlueABILITY Model”. This complex model included a multitude of elements ranging from exposure to context, and from health and wellbeing to barriers and enablers. Using AT is included as a minor aspect of this dynamic model.

There is no known study that specifically explores the use of AT to access beaches. There are however studies focused on ecotourism identifying the value of ensuring beaches are accessible. Such studies highlight the importance of availability of AT such as beach wheelchairs and walkers. A tourism study explored the accessibility of 90 beaches in Spain, using a 24-item researcher-created audit tool, “The Beach Accessibility Index”. This tool included one AT specific item “service has bathing support materials”. This study showed 86% of the surveyed beaches did offer AT such as wheelchairs, hoists, walkers, and floats. A Korean survey of 110 tourists who used Beach AT on a tour reported 100% satisfaction with the buoyancy and weight of a beach wheelchair, but only 83% were satisfied with the mobility of the chair. No further insights were reported on the experience for these people. Such studies indicate a tourism value but do not address the personal individual experience and meaning for people with mobility impairments who may use AT for regular leisure pursuits.

The most comprehensive known study to explore disability inclusion at beaches adopted a community development approach. This Australian mixed-methods study explored 30 community development projects and 3 local government projects which all facilitated beach access for people with any disability [Citation4]. This study identified the complexity of beach inclusion. This involves building relationships, providing opportunities for people to develop skills, the acceptance of people with disabilities on the beach, as well as physical access to the beach and beach activities. Access includes infrastructure as well as AT. The use and or provision of AT is only one aspect of this, however this was identified to be essential, especially for those with mobility impairments whose primary barrier is physical access to sandy beaches.

A recent Australian survey of older people and people with a disability (n = 350) also highlighted the barriers and facilitators to beach access [Citation5]. Infrastructure including pathways, walkways, and parking were the most frequently reported facilitators of beach access. Respondents also reported common barriers including difficulty mobilising on sand, difficulty accessing the water and limited Beach AT.

Assistive technology benefits people with disabilities directly and any research or inquiry should include the users’ perspective [Citation6]. Understanding the meaning of AT use from the users’ perspective provides insights into the complexity of AT, which reaches beyond device specifications. The meaning of using various AT has been described as complex or even transactional, where the user has to evaluate their expectations of the AT with their experiences to decide if it is worth using [Citation7]. These transactional experiences have been described as a “challenge” based on the interaction between overcoming the “hassle” and enjoying the benefits of the “engagement” as a result of the AT use [Citation8]. Examples of how AT use has benefits as well as challenges are evident in a metasynthesis of the use of wheeled mobility devices which showed that people find wheeled mobility devices to be both enabling and disabling at the same time. These experiences are also impacted by the environment, sociocultural interactions as well as occupations and activities of the person adding another level of complexity [Citation9]. Another review of studies that explored the use of prosthetics showed that the AT impacted peoples self-identity, enabling expression but also impacted their social interactions both in terms of stigmatization as well as normalcy. Similarly, the use of speech generating devices was also found to have benefits as well as challenges for users. Speech generating AT was inefficient, impacted by societal expectations but also enabled social participation [Citation10]. It follows that understanding the lived experience of using any AT including Beach AT warrants in-depth exploration.

There is growing understanding of leisure for people with mobility limitations including activities of kayaking, snow sports and adaptive hiking [Citation11–13]. Findings from these studies support the meaning and importance of access to outdoor recreation. A Canadian study exploring 19 users’ perception of AT for people with SCI highlighted the benefit of AT to facilitate leisure such as sledge hockey and it associated benefits [Citation14]. A Norwegian study focused specifically on AT for leisure for 44 people with mobility impairments also evidenced the benefits of leisure AT [Citation15]. Leisure AT allowed people to feel included, as well as enabled them to be able to spend time in solitude. Participants also valued the opportunity for mastery and independence in leisure. A Canadian interpretive descriptive study, involving fifteen people who use wheeled mobility devices to participate in informal outdoor recreation, highlighted the difference between formal and often “oversubscribed” recreational adaptive leisure and informal spontaneous leisure which would include going to the beach [Citation16]. Findings include the need for developing new adaptions to existing AT as well as having access to affordable AT. These Canadian participants also identified a desire to access beaches.

In Australia beach base leisure is highly valued by society [Citation17]. Australia has 314 beaches which are patrolled by Surf Life Saving Australia (Australia, 2021) and of these 41 are listed in the Accessible Beach Directory (Beaches, 2021). Inclusion on the list is granted to those beaches that provide AT products and services such as beach wheelchairs and mats to facilitate beach access for people with mobility impairments. In Australia funding from the National Disability Authority is available in the form of personalised National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) plans for people under 65. These plans can include any reasonable and necessary goal, such as a plan for beach access. This means there are opportunities for people with mobility impairments to purchase and own their own Beach AT. Evidence supporting the use of beach AT may inform future advocacy for such items.

It follows that prescribers and advisors of Beach AT can benefit from an understanding of the users’ perspective of using such technologies to inform their practice. Local communities and authorities can also benefit from understanding the use of AT to inform future development and acquisition of resources in the community which may include AT. Therefore, this study explored the research question, “What is the lived experience of using assistive technology to facilitate sandy beach-based leisure activities for people with mobility impairments in Australia?”

Methods

Research design

This phenomenological qualitative study aimed to explore the lived experiences of people with mobility impairments and their use of Beach AT. This was initially guided by the interpretative hermeneutic Sheffield school approach [Citation18,Citation19] also called descriptive phenomenology [Citation20]. This phenomenological approach seeks to explore the lifeworld of participants, in this case the lifeworld of Australians with mobility impairments using Beach AT. This approach lists ‘fractions’ to consider when collecting and analysing phenomenological data. Ashworth [Citation19] explains that these ‘fractions’ are not ‘definitive’ but rather offer aspects to consider when conducting descriptive phenomenology. This involved considering embodiment, sociality, temporality, spatiality, selfhood, as well as the discourse used to describe the experience itself, and the moodedeness of the experience. Considering these elements facilitates a phenomenological depth of investigation.

This approach was deemed appropriate as this study did not seek to develop a theory as is customary in grounded theory. In aligning with qualitative phenomenological enquiry analysis, we did not employ any counting or quantifying approaches to indicate “strength” of codes or themes, as is required in other approaches such as content analysis. Quantitative research was not considered suitable as it was assumed that the target population itself is relatively small, as few people have access to Beach AT for leisure. Furthermore, the use of quantitative inquiry would assume some preceding understanding of this experience on which to base specific questions.

The research team sought feedback and direction in the planning stage by consulting with two people with mobility impairments. They confirmed the direction of the study, as well as the studies relevance to those who have mobility impairments seeking to access the beach. Furthermore, they helped adjust the research question as well as the questioning guide. Ethical approval was granted by the University of the Sunshine Coast’s Human Research Ethics Committee (S211589). The research team also adopted reflexivity practices of journaling and discussion [Citation21].

Recruitment

Recruitment was conducted online via social media platform Facebook, with invitations to seek participants shared with 16 Australian-based disability sites. This allowed word of mouth and social media snowball sampling [Citation22]. Participants were then selected using purposive sampling, aimed at seeking people with experience of using Beach AT [Citation22–24].

Eligible participants self-identified as having mobility limitations, lived in Australia, and were aged between 18 and 65 years. These selection criteria were chosen to create sample of Australian beach-users, whom had experiences of using Beach AT to overcome mobility restrictions [Citation25]. This sample was also reflective of those who would qualify for NDIS funding which could include Beach AT (thus excluded those over 65). It was expected that around 10 participants would be recruited, which is a typical sample size in phenomenological research [Citation26].

Data collection

Data was collected using open ended semi-structured interviews [Citation27] with photo elicitation [Citation28]. Open ended questioning allowed for participant reflection, as well as opportunities for follow-up questioning to seek depth and clarity of responses. Participants provide informed consent prior to interview. All interviews were conducted by the same author (LW) who was trained in qualitative interviewing by the research team. Training included a pilot interview to test the questioning guide and to ensure an open-ended interviewing style. The pilot interview data was not included in analysis.

Interview questions focused on the experience of using AT for engaging in beach leisure. Photo elicitation was incorporated to facilitate open conversation. The interviewer asked the participants to: describe their photo; their reasons for including the image; to identify anything missing in the photo and to describe any emotions associated with their image. This led to further questioning using open-ended questions such as: “Please describe the assistive technology that you use for sandy beach-based leisure?”; “Talk me through a typical day at the beach?”, “Tell me a little bit more about yourself as a beachgoer” and “What would that experience be like without assistive technology?” The interviewer probed responses by asking for extra clarity for example, “can you tell me more about that?” and “how is that experience for you?” add extra open questions to facilitate more extensive descriptions.

Data was collected during the COVID-19 pandemic and therefore the use of video conferencing (Zoom) was required. This inadvertently provided added opportunity for the sharing of extra images using screen sharing options, this provided some contextual information such as websites describing specific AT devices during interviews. This extra data was not included in analysis but did contribute to the flow of conversation facilitating detailed responses. The interviews were preceded by an invitation to participants to share their own photos or video of their beach leisure. The purpose of including images, known as photo elicitation, was to facilitate discussion aimed at fostering a collaborative research relationship [Citation28].

Participants who chose not to share imagery or left their cameras off during their Zoom session were not excluded. Participants choose whether they wanted to use a pseudonym and whether they wanted their images made available in dissemination (see an example, ).

Figure 1. Research participant supplied photo, using AT to access beach with their dog.

Within one month (12 July − 12 August 2021) 14 participants were interviewed and data collection ceased. The sample size allowed a focus on depth rather than breadth of understanding [Citation25]. Interviews took ∼30–90 min each with an average of 66 min. Interviews recordings were transcribed verbatim professionally. While member checking of transcripts was offered to participants, along with copies of their recorded interview or transcript, no feedback was received from participants.

Data analysis

Data was analysed through a phenomenological lens using Braun and Clarke’s [Citation29] reflexive thematic analysis which updates their earlier ‘six step process [Citation30]. This began with familiarisation with the data as all three of the research team repeatedly listened to the interviews. Each researcher contributed to reflexive journaling after listening to the transcripts as well as during analysis.

A phenomenological lens was used in the initial stages of coding as transcripts were hand coded by LW considering lifeworld aspects of embodiment, temporality, spatiality, moodedness, sociality, project, and selfhood [Citation18,Citation19]. The generated initial semantic codes reflective of the lifeworld fractions and associated verbatim quotations were checked and agreed upon by the research team preceding further analysis. Transcripts were all re-analysed according to semantic codes and checked by all members of the research team using NVivo as a data management tool.

The research team then interrogated the themes to generate latent themes guided by the research question focused on the lived experience of using Beach AT. This involved collapsing and merging similar codes into themes. This involved whiteboard mind mapping, and peer feedback from academic peers not involved in analysis. Interrogation of analysis sessions by the research team were used to review, define and name themes. Debate and discussion lead to a final identification of overarching themes underpinned by the latent themes. See for a sample of coding progression from lifeworld fractions to semantic codes, then latent themes into overarching themes. Following thematic analysis, the research team cross checked reflexive journal entries and transcripts to ensure that themes remained faithful to the participants’ lived experiences.

Table 1. Example of coding thematic progression from lifeworld fractions, to semantic codes, to latent themes and overarching themes.

Strategies used to strengthen rigour included a review of previous research, use of recognised methods (The Sheffield School Phenomenology and Reflexive Thematic Analysis); targeted recruitment of informants who provided rich description; and intense periods of time spent in data analysis [Citation31]. Purposeful sampling was aimed at facilitating transferability to an Australian context reflective of this sample – namely people who have access to Beach AT. Triangulation involved peer checking throughout data analysis to reach consensus codes and themes [Citation22]. Furthermore, the use of a reflexive audit trail included a record of methodological decisions, day to day procedures, evolving perceptions and logged personal introspections after interviews to consider how potential researcher bias may have impacted the data [Citation32]. For full transparency and trustworthiness, it is important to acknowledge the beliefs and preconceptions and position of the three researchers [Citation32] who were all able-bodied and occupational therapists with assumptions and biases that AT enhances equitable access, improves participation, and strengthens subjective health and wellbeing. Researchers were all beachgoers with assumptions of beach leisure as valued and meaningful.

Findings

A sample of 14 people participated in this study. See for demographic details. Participants ranged from 25 years of age to 65 years of age. There was a wide range of primary physical disability. All 14 participants had lived experience of utilising AT to participate in sandy beach based leisure (SBBL). Participants were referred to by their first name or by the pseudonym they requested. Twelve of the participants resided in Queensland. Photos were provided by 11 of participants. These were not included in the analysis used only to facilitate discussion. (See )

Table 2. Participant demographic details.

Data was analysed in response to the research question “What is the lived experience of using assistive technology to facilitate sandy beach-based leisure activities for people with mobility impairments in Australia?” Analysis identified 10 themes arranged into three overarching themes: 1) Meaning, 2) Practicalities and 3) Responses to using Beach AT (see ).

Figure 2. Themes and subthemes of the lived experience of using beach assistive technology for people with physical disability.

The meaning of using Beach at

This overarching theme has three subthemes: 1) AT connects me; 2) AT impacts my identity and 3) AT attracts attention.

At connects me

Participants shared that Beach AT “gets me out of the house”, and that the AT increased opportunities to “participate more in the community and with friends”. Many articulated that it enabled a return to leisure activities such as swimming, surfing, dog walking, boating, fishing, and outdoor sculptures by the sea. Jack said, “I actually put a foot down on the sand!” Similarly, Adrienne shared, “It’s changing from a 2D world restricted to the boardwalk, to a 3D world where you’re a part of it, rather than just looking at it [the beach]”. She also said, “I thought of [the self-balancing two-wheel power wheelchair] as a mobility device, but it’s actually this amazing mental health device as well …[because] it’s a huge lift, to be outdoors”.

Participants described beach leisure as grounding, spiritual experiences that connected them to their surroundings. They talked about being in nature, appreciating the vast open space, and being immersed in sensations like “the way the water feels on my skin”, smelling the ocean breeze, feeling the sea spray, and hearing the “roar of the ocean and the crashing of the waves”. Douglas reflected on this common thread, “You’re part of society, […] you’re at one with nature again, and that’s what we’re all trying to do, connect with our environment”.

Others indicated that beach access was a human right and that heading to the coast for a day out was “part of Australian culture” allowing “a normal life”. They described that it can, “bring back good memories” and for some it was integral to building memories for their own children.

At impacts my identity

Beach AT that enabled beach access was described as “makes life worth living”. Accessing the beach to participate in leisure through the use of Beach AT, was described as enabling participants to reconnect to their sense of self, either as an outdoors person, a water person, an athlete, or an active fun dad; “[My motorised manual wheelchair track attachment] enables me to move around on the beach and chase a cricket ball or chase the kids around or build sandcastles” (Dane).

Gayle who uses a beach mat and manual chair to reach the ocean said, “[The beach] makes me feel normal, alive. […] I'm not disabled in the water”. “It just reconnects me with the way life used to be before I had the accident”, mentioned Jacko adding, “Without the [prosthetic] legs, I probably still wouldn’t be going down to the beach”. Katie articulated “I grew up on a beach, so it’s actually my centre. It’s my soul. It’s something that is a part of […] who I am and identify with”, a sentiment echoed by Shane, “The beach, it’s just part of my life, it’s part of who I am, it’s part of my identity.”

On one hand, many voiced that Beach AT when used independently led to a sense of empowerment, by enabling a return to ‘normal’. For others when AT required other people to operate it, if it was unavailable, or could not be mastered, participants described this as limited as they became static onlookers. For example, “I kind of end up the look-after-the-gear person” or they would read a book as they waited for others to enjoy the beach reporting that, “I’m now a bystander of my world”. This led to some participants feeling excluded, and or reluctant to use AT.

I need to make this look flawless … if I can’t do that then people will think I have a disability when I'm trying to just live my life and show people that I can do anything I want to do. [So] If it can’t make it look flawless, then I don’t want to do it… (Jimmy)

At attracts attention

The attention that Beach AT drew from strangers polarised participants with some indicating they felt it was positive and others articulating it induced negative emotions. Some participants indicated that they welcomed interactions as an opportunity to receive hands-on help when bogged in the sand, or when lifting their chair onto the back of a car.

Wil perceived the attention he receives as an affirmation of his ingenuity. “While we’re waiting for the waves, you just have a bit of a chat, … I've got some rubber blocks made, foam blocks that I kneel on, to protect my legs. …. It’s always a discussion point. [Or] they see me using [my customised Canadian crutches] as I come in or out of the water and … say, ‘That’s a great idea, how did you make them?’”

Viewing interactions as a positive was further supported by Dane who described, “Every time without fail, we go to the beach, there’ll be someone that comes up… ‘Oh, how good is that you get down onto the beach’. … I don’t mind […] I see it in an educational type, disability awareness type way”.

Conversely some participants talked about unsought interactions making them a target for attention, making them feel embarrassed by being the “centre of attention”. Similarly, there were some descriptions of interactions when using Beach AT which ranged from thoughtless and rude to “hindering” and “hateful”.

Practicalities of using Beach at

The overarching theme, Practicalities of using Beach AT encompassed four subthemes: 1) Using AT requires other people, 2) AT impacts spontaneity, 3) AT limitations, and 4) AT use differs in water.

Using at requires other people

Most participants stated that even when AT is available, participating in SBBL requires some level of assistance. “[beach wheelchairs] don’t give you any independence. You’ve got to rely on somebody else to push you” was a common refrain from participants. Soft sand was described as compounding their disability by reducing mobility and or their independence. The real risk of getting bogged meant that for some they would not go onto the beach or leave the boardwalk without a companion.

Further assistance was required for: packing AT in the car; changing power chair tyres; pushing beach wheelchairs on the sand; aiding transfer in and out of chairs in the water or being on hand in case things went wrong such as being bogged in the sand, or when too fatigued to walk or push up the beach mat gradient or being fatigued by waves and breakers.

Unless you’ve got family or friends or carers with you, you can’t go to the beach. It’s just too hard. […] Packing, setting up, getting everything in the car. It’s a lot of work […] without people helping you, you just can’t do it. (Adrian)

“Theoretically, I can now go on the beach (using AT), [but] I'm either going to have to have [my partner] … with me or somebody else who can lift the [AT] (off road wheelchair power track attachment) because it’s more than 25 kilos” articulated Savannah. SBBL was reported to be challenging. Jimmy describes,

You’ve got someone else carrying all your stuff because […] when you’re on the beach, you really need to lean over your lap to push as hard as you can (Jimmy).

For some, when other people helped with their AT, they felt unsafe and or disempowered, “People with all good intention, like they push you, but then they leave you parked, […] up against a wall, looking at a wall” reported Adrienne. Savannah echoed feeling unsafe and disempowered by her father,

I was like, ‘No, dad, I don’t want to go too far away because this is the first time that I've used this device. And I don’t want to end up two kilometres down the beach and we need help. […] can we turn around and go back?’ And he’s like, ‘No, no, no, no, it will be fine. Let’s go down the beach.’ And I was like, ‘God, Lord, turn around’ […the experience] made me feel like a kid”.

At impacts spontaneity

Most participants discussed Beach AT as requiring some level of planning. The majority of the participants reported the need to organise a support worker, friend, or family member in advance was a crucial step to SBBL success. “If you wanted to down onto the beach, there’s so much planning and preparation that goes into it” identified Douglas, who alongside others, described planning as a reality even when they would prefer to be spontaneous.

I want to be able to be spontaneous […] wake up and go and not have to go, ‘Oh, if only we planned this two days earlier and made that phone call two days ago and booked in that time with that chair’. (Dane)

While Katie articulated that she manages to stay spontaneous by selecting beaches with ramps and leisure activities that minimise the amount of AT or other people required in advance, “I'm fiercely independent, [to ensure] I do everything on my own. I just need to plan it a little bit better”.

Others described the importance of researching beach locations, public transport, beach access, disability parking and change rooms, beach mat hours and booking beach wheelchairs via websites, social media forums and or phone in advance. “Usually on a Thursday, I'm already looking at the next week … that I know what I'm going to do and how I'm going to deal with it,” described Savannah who described charging, packing, and transporting AT as items on her beach going checklist.

At limitations

Participants reported several AT limitations. “I'm yet to find the perfect piece of AT,” was a common refrain from many participants. They described having to weigh up their desire to independently self-propel and to meet their leisure goals against environmental demands of the sand or ocean and feature limitations of available AT.

With my [power track system], I can move around independently on the beach. …The limitation to it is that it’s an electronic piece of equipment and electronics and salt water don’t go well together. [In a manual chair] I could go out to waist height … get wet and get amongst it … But then the trade-off is I can’t chase the kids around the beach. (Dane)

Sand was described as a “killer” not just for their bony prominences but also for AT with sand causing casters and or bearings to seize and fail.

I just won’t use my day chair on the sand. One, it’s too difficult. Two, it can cause injury because you’re straining yourself. Three, your chair is not designed for salt and sandy conditions, so it’s going … [do] damage to your equipment. And if that happens, then it affects your independence (Shane).

The (beach wheelchair) was [still quite hard to push but] great for going along the sand … the front wheels made the chair buoyant, so it made it harder to get out of the water [and] getting in was horrible (Douglas).

Every person with a disability has a different ability level, and every person with a disability has different goals about how they want to enjoy the beach […] So, it’s about having a range of different equipment for a range of different ability levels, body shapes, sizes [available to use] (Shane).

Beach mats too received a mixed report. Some participants articulated that they were “life changing” a “fantastic idea” when readily available or executed well. However, others voiced they were a “waste of money” when provided without shade, no passing lane, parking or turning bay, or were too short to “get you down to the hard sand, which is where they need to get to for you to be able to be independent” (Lachy).

At use differs in water

Participants expressed how the demands of their chosen leisure activity and or environment dictated their AT requirements, with a clear line drawn between water and sand-based leisure AT. Each of these environments posing different challenges and opportunities for participants with AT required in a variety of combinations. Including AT beforehand to access SBBL, AT during to perform SBBL and or AT following SBBL participation.

For those entering the water there were a range of items that considered to be AT. These included standard watercraft, paddles, wetsuits, ankle weights, customised personal flotation devices. Sea scooters were used to increase swimming duration and reduce fatigue. Motorised surfboards and Personal Flotation Device were used when surfing to minimise risk of drowning and water shoes to protect skin integrity for those with sensory deficits against oyster shells and submerged rocks.

Responses to using Beach at

The third overarching theme, Responses to using Beach AT included three subthemes: 1) I didn’t think it was possible, 2) Adaptations to AT limitations, and 3) Not everyone wants to own AT.

I Didn’t think it was possible

Some participants reported that they had been excluded from SBBL post injury, illness, or impairment for 18 months to 15 years. As Adrian shared “[After my injury] I thought that was it. No more beach”. Participants mentioned opportunities to try AT via surf lifesaving clubs was when they first realised that SBBL was possible.

The first time I found a beach mat, I was just overwhelmed by it. Thank God, someone’s thought of this. … to be able to do something … that I thought was gone (Gayle).

The majority said that organised opportunities to trial equipment created by occupational therapists, rehabilitation services, advocacy groups and specialised accessible resorts were a crucial step in their journey back to the beach.

I really didn’t think I'd be able to go back into the water” [until my occupational therapist] told me about this Freedom Trax. So, … arrange as many trials of equipment as possible. Because it wasn’t until [then] that I was like, ‘Yeah, okay, this could work’ (Savannah).

Adaptations to at limitations

Participants had diverse responses to Beach AT limitations. Some chose to avoid the beach, or to stay on the boardwalk. Alternatively, others compromised their everyday wheelchair to fulfil their SBBL goals despite acknowledging the negative impact of sand and saltwater on their wheelchairs. “The chair needs to live your life, not you live accordingly to suit your wheelchair” (Jimmy).

Others modified their AT. Wil filled his Canadian crutches with foam pieces, attached pool noodle sheaths and added rubber disc feet to traverse the sand. Douglas designed foam steps to aid water transfers and Martin printed a 3D drone joystick to enable him to ‘virtually’ participate in family walks along the beach. Aidan adapted a car bike rack to carry a large power wheelchair rather than requiring a trailer. Some participants avoided peak times to overcome lack of accessible parking required to unload AT. Further adaptations included avoiding the challenges of sand and breakers by approaching the beach via boat.

Not everybody wants to own at

Many participants reported that they did not want to own Beach AT. Reasons for this point of view were related to the limitations of the AT which included reports of the beach wheelchairs being difficult to propel and “bulky” to transport or store. The initial cost of purchase and ongoing maintenance was a concern given they were often still dependent on others to propel the beach wheelchair and that the AT was not used regularly. Instead, some expressed that in an ideal world a range of AT would be available 24/7 to borrow or hire at all patrolled beaches by anyone in the community who may benefit from it.

Discussion

This study explored the lived experience of sandy beach-based leisure participation using AT for people with mobility impairments. To the authors’ knowledge, this project is the first qualitative study focused on beach AT. Findings add to the existing understanding of the benefit of AT as an enabler of participation in outdoor leisure activities, specifically in beach environments. It is also the first to focus on beach leisure for people with mobility impairments.

This phenomenological study showed that the lived experience of people with mobility impairments using Beach AT included meanings of the Beach AT, practicalities involved in using Beach AT, and the users’ responses to Beach AT use. These overarching themes all include descriptions of both benefits and challenges of using Beach AT. Findings were related to the meaning of beach leisure itself, while also providing some insights into the meaning of AT used to access this specific leisure environment.

Meaning

The first overarching theme of the lived experience of people with mobility limitations using Beach AT was about the meanings of using AT to engage in beach leisure. This included connection, identity and attracting attention. The first two themes, connection and identity, may be attributed to the beach leisure itself with the AT as an enabler thereof. Findings describe a connection to their previous lives as well connection to community. Findings also show that these participants were able to enjoy benefits previously identified in Blue Space research [Citation1] through using Beach AT as well as benefits of nature-based leisure for people with mobility impairments [Citation33].

The benefit of restoration was evident in our findings reflected as experiences of spirituality enabled by being outdoors at the beach. Findings of this study of Beach AT enables connection to their natural surroundings with time for reflection aligns with the benefit of AT providing an opportunity for solitude in leisure activities described for Swedish people with mobility limitations [Citation15]. Blue Space benefits of connection [Citation2] were also identified in the lived experience of connection for participants to community, family, and friends.

Beach leisure also impacted peoples’ identity in a positive way, re-establishing links with past identities and feeling “normal”. This was attributed to being able to participate in SBBL again or for the first time. Similarly participating is adaptive recreation has been attributed to allowing normalcy [Citation34].

While connection and identity have clearer links with beach leisure itself, the theme of attracting attention relates more specifically to meaning of Beach AT itself. Some experienced attracting unwanted attention while using the Beach AT. It was not clear from our data if this attracting attention was unique to using Beach AT specifically or if it was the same as attracting attention and the associated experienced stigma of disability, signposted by the use of any AT device. Similar experiences have been described by people with mobility impairments as stigma of disability highlighted through the use of wheelchairs [Citation35,Citation36] or prosthetics [Citation37]. In our study however not all saw attracting attention as a negative attributing this as an opportunity to normalise and educate people about beach participation for people with disabilities.

Practicalities

The benefits of using beach using AT was balanced with description of the practical realities for participants. Practicalities described by participants illustrate that, although SBBL is meaningful and beneficial the lived experience can be challenging. This included the challenges of requiring other people, not being able to be spontaneous as well as encountering of device limitations.

Established benefits of outdoor leisure for people with mobility impairments include opportunities for solitude as well as mastery or independence in leisure, implying being alone and not needing assistance [Citation15]. These benefits are limited in our study which shows that using Beach AT requires other people. Help is required to be propelled, to assist in transfers, to lift, to set up and transport. The requirement for assistance is evident for Beach AT especially large bulky beach wheelchairs. The need for physical assistance to enjoy the beach has been reported to also include physical assistance for participating in beach and ocean activities as well as for transfers and personal care [Citation5].

This requirement, for others to assist in the use of AT, is not unique to Beach AT. Successful use of complex devices like AAC requires set up and skilled communication partners [Citation10], Other adaptive leisure pursuits, like hiking and kayaking also rely on the assistance of able-bodied people [Citation16]. Furthermore, the need for the help of others is a significant challenge and a lack of volunteers can lead to the cancelation of outdoor activities such as adaptive hiking [Citation13]. In Australia Darcey et al. [Citation4] clearly identified the challenge of requiring lifesavers or lifeguards to enable beach wheelchair use. This limits the opportunity and spontaneity for users as these services are not available permanently and can be dependent on staffing, schedules and beach conditions. However, Australian survey data does report that booking systems and calendars for beach AT are common facilitators of beach access [Citation5].

It is however important to also acknowledge that beach leisure is often a social activity. It follows that for some, this reliance on others was not a significant challenge as beach leisure usually includes family and friends who were described as happy to assist and in some cases the Beach AT allowed the users to also offer help to family by watching and playing with children.

Using Beach AT was also found to impact spontaneity and required planning. This is not unique to Beach AT as a Canadian outdoor recreation study for people using wheeled mobility devices identified similar planning challenges and the inability to be spontaneous [Citation16]. Outdoor leisure inherently requires planning, but the addition of leisure specific AT, such as beach wheelchairs, increased the planning required to include packing, charging and transporting AT. It is not clear if using other AT devices also impacts spontaneity. Our study did not explicitly explore comparisons with participants’ other devices. It is important to acknowledge this specific frustration with beach leisure which as an able-bodied activity may be perceived to be inherently spontaneous is not the same when Beach AT is required.

Challenges to the use of AT were included limitations of Beach AT device use. These included challenging attributes of the devices including large size and being difficult to self-propel. The physical beach environment of sand, water and salt were also challenges as Beach AT requires different specifications to address all of these elements, but no one device was considered suitable to address all of these. It also follows that one of the challenges of Beach AT is the difference of requirement for sandy versus wet leisure. A beach wheelchair designed for water entry is unlikely to also be ideal for negotiating long distances on a sandy beach. On the other hand, motorised devices are not suited to wet and salty environments. It follows that the user needs to identify what leisure activity they want to engage in and choose Beach AT accordingly. Alternatively, beach users with mobility impairments may require more than one device.

Responses

In-depth investigation into lived experience provides opportunity to explore individual insights beyond the expected or known barriers and enablers. In this study participants described both surprise and ingenuity in their responses to using Beach AT. They were surprised that beach leisure was possible, showing the importance of the opportunities to experience and trial Beach AT people otherwise people may never be aware that they can engage in beach leisure again. Beach wheelchairs, specifically, are large expensive items that people may not have opportunity to experience. These trials may be part of occupational therapy planning and assessments, supplier trials, organised beach activities such as Disabled Surfers, or using a beach chair at a surf lifesaving club.

AT trials are recommended as ethical and appropriate ways to limit abandonment and misuse of AT by allowing the prescriber and client to interact with the AT and understand practicalities before seeking funding or purchasing AT [Citation38,Citation39]. Trials usually inform future acquisition of AT, however in the case of beach wheelchairs it may be preferable to have access to a community source of these devices. It is however still important for the user to understand their personal device requirement so they can evaluate the suitability of publicly available Beach AT to limit injury or poor user experience.

Initial expectations of this study identified through reflexive journaling was to understand benefits of owning one’s own Beach AT, with an assumption that this study may support future Beach AT purchases, which may be part of individual funding such as a NDIS package in Australia. It is a surprising result the personal ownership of such devices was contended in the findings. It was evident that due to limitations of specific Beach AT some participants identified that owning your own Beach AT is not ideal. Participants described reasons for not owning their own Beach AT, including that they may need more than one type of device for example a manual wheelchair for accessing the water as well as a powered all-terrain wheelchair for playing on the beach with their children.

However, access to beaches still requires AT and thus the study supports the importance of publicly available Beach AT. Darcey et al. [Citation4] however echoed some challenges described in this study. The provision of Beach AT is limited by location, day, time and goodwill, further amplifying the experience of decreased spontaneity for those who require AT. Tourism studies acknowledge the importance of publicly available Beach AT [Citation40,Citation41] and findings from this study further support this. Public access to Beach AT requires significant investment at a community level as opposed to individual funding. It is acknowledged that in Australia local authorities and surf lifesaving clubs have begun to supply such items in some communities, but there is no known research to evidence the impacts of this.

Participants also demonstrated ingenuity as well as personalisation for successful use of AT. These adaptations included the use of strategies such as selecting appropriate times for going to the beach or overcoming the surf break by entering the water by boat. Some made physical adjustments to devices by adding floats, increasing surface areas or using devices that they were not suited to. These descriptions highlight that use of AT extends beyond the device itself requiring users to address both the hard and soft technology [Citation42] requiring set up, and monitoring of AT. In the case of Beach AT, it is important that selecting the correct device is not sufficient and ongoing support is needed to enjoy the benefits of this AT especially if the chosen leisure activity might change.

Strengths and limitations

The sample of 14 participants were able to provide rich data to address the research question, “What is the lived experience of using assistive technology to facilitate sandy beach-based leisure activities for people with mobility impairments in Australia?” Individual response bias was possible, reflected by a large Queensland sample possibly a result of the snowballing recruitment. However, the sample included a range of participants in terms of disability, a range of AT and a range of leisure activities thus reflecting diversity within the sample. Further response bias was possible through attracting people who feel and speak positively about Beach AT. This was however not overt in the findings which included both positive and negative descriptions. The sample was restricted to those under 65 years of age meaning that it does not include the experiences for those with disability associated with aging. Recommended future research should include participants from a wider geographical area, and older adults.

One limitation of the findings of this study are the specificity of the predominately Queensland, Australian setting. This unique context is underpinned by an Australian beach culture, as well as a perceived opportunity for individually owned Beach AT through NDIS funding. Findings do however offer insights for other settings. This study indicates that the opportunity for a person to own their own Beach AT may not be preferred and thus add weight to initiatives and the studies described in countries like Spain and Korea to have publicly accessible Beach AT. Similarly, being able to use Beach AT to engage in SSBL translates to environments outside of Australia in terms of the meanings of connection and identity.

This study suggested some similarities and differences between land-based AT and Beach AT however this exploration did not explicitly include a comparison to participants’ other AT. This is a possible limitation of the questioning guide and future investigation should include such comparisons.

While this study focused specifically on the Beach AT a fuller understanding of beach access as suggested by the “BlueABILITY Model” and previous Community Development research is required. The scope of this study did not focus on challenges and barriers of beach-based participation, although findings provide insights into these. Although interviews did include reference to the built environment (including changing facilities and ramps) further research to explore the built and social environments’ impact on beach leisure for people with mobility impairments is recommended.

Future research needs to investigate the impact, including challenges and benefits of publicly available Beach AT including wheelchairs and matting. This will support ongoing investment and expansion, should assess feasibility, and maximise uptake

Conclusion

Beach AT allows users to enjoy the benefits of Blue Space and beach leisure, such as enabling connections to social groups, outdoor environments as well as contributing to a person’s identity as a beachgoer. Access to Beach AT is important and may be made possible through personal ownership, or by loaning equipment. Trialling of Beach AT as precursor is advisable. When using Beach AT, it is important to acknowledge both the benefits and the challenges. Pragmatic challenges related to size, storage and propulsion. In some case the challenges may outweigh the benefits. For others challenges can be overcome through adaptation such as adjusting physical devices and practice using. While Beach AT use has some similarities to experiences with other AT, specific differences relate to the large physical size of some devices, as well as the complexity of the varied environments of sand water and salt that these devices are intended to be used in. Satisfactory use of Beach AT for a person with mobility limitations requires the user to identify how they plan to use the device considering water and sand as different environments. Users’ realistic expectations need to include an understanding that the AT may not enable spontaneity or full independence, or and that help from others may be required. Users also need to acknowledge that use requires planning in contrast to desired spontaneous beach leisure. This phenomenological study which explored the lived experience of using Beach AT to engage in SBBL adds to the limited knowledge of Beach AT, acknowledges some challenges but also highlights the benefits of beach leisure and required Beach AT as a facilitator.

Acknowledgments

The research thank the 14 participants who so generously shared their time, their lives, and their rich lifeworld views. The people who assisted in recruiting participants from Spinal Life, AT Chat, Community Disability Information Alliance, Physical Disability Australia, Assistive Technology, Australian Rehabilitation & Assistive Technology Association and Push Mobility. Special thanks to April Sweet for her editorial assistance and useful commentary. Thanks also to Laura Burritt and Kerri-Anne Von Deest for providing commentary on earlier versions of this paper.

Disclosure statement

One author declares a conflict of interest as a board member of a national assistive technology peak body, Australian Rehabilitation & Assistive Technology Association, with a focus on equitable access to AT for all. Another author declares a conflict of interest due to their professional business which includes making recommendations for SBBL AT for their clients.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Georgiou M, Morison G, Smith N, et al. Mechanisms of impact of blue spaces on human health: a systematic literature review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;318(5):2486.

- Britton E, Kindermann G, Domegan C, et al. Blue care: a systematic review of blue space interventions for health and wellbeing. Health Promot Int. 2020;35(1):50–69.

- Job S, Heales L, Obst S. Oceans of opportunity for universal beach accessibility: an integrated model for health and wellbeing in people with disability. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2022;46(3):252–254.

- Darcy S, Maxwell H, Edwards M, et al. Disability inclusion in beach precincts: beach for all abilities – a community development approach through a social relational model of disability lens. Sport Management Review. 2023;26(1):1–23.

- Job S, Heales L, Obst S. Tides of Change-Barriers and facilitators to beach accessibility for older people and people with disability: an Australian community survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(9):5651.

- Buchanan R, Layton N. Innovation in assistive technology: voice of the user. Societies. 2019;9(2):48.

- Krantz O. Assistive devices utilisation in activities of everyday life-a proposed framework of understanding a user perspective. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2012;7(3):189–198.

- Verdonck M, Steggles E, Nolan M, et al. Experiences of using an environmental control system (ECS) for persons with high cervical spinal cord injury: the interplay between hassle and engagement. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2014;9(1):70–78.

- Ripat J, Verdonck M, Carter RJ. The meaning ascribed to wheeled mobility devices by individuals who use wheelchairs and scooters: a metasynthesis. Disab Rehabil Assist Technol. 2018;13(3):253–262.

- Ripat J, Verdonck M, Gacek C, et al. A qualitative metasynthesis of the meaning of speech-generating devices for people with complex communication needs. Augment Altern Commun. 2019;35(2):69–79.

- Mavritsakis O, Treschow M, Labbé D, et al. Up on the hill: the experiences of adaptive snow sports. Disabil Rehabil. 2021;43(15):2219–2226.

- Merrick D, Hillman K, Wilson A, et al. All aboard: users’ experiences of adapted paddling programs. Disabil Rehabil. 2021;43(20):2945–2951.

- James L, Shing J, Mortenson WB, et al. Experiences with and perceptions of an adaptive hiking program. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40(13):1584–1590.

- Ripat JD, Woodgate RL. The role of assistive technology in self-perceived participation. Int J Rehabil Res. 2012;35(2):170–177.

- Pedersen H, Söderström S, Kermit PS. The fact that i can be in front of others, I am used to being a bit behind": how assistive activity technology affects participation in everyday life. Disab Rehabil Assist Technol. 2021;16(1):83–91.

- Menzies A, Mazan C, Borisoff JF, et al. Outdoor recreation among wheeled mobility users: perceived barriers and facilitators. Disab Rehabil Assist Technol. 2021;16(4):384–390.

- Fiske J, Hodge B, Turner G. Myths of Oz: reading Australian popular culture. New York: Routledge; 2016.

- Ashworth P. An approach to phenomenological psychology: the contingencies of the lifeworld. J Phenomenol Psychol. 2003;34(2):145–156.

- Ashworth PD. The lifeworld - enriching qualitative evidence. Qual Res Psychol. 2016;13(1):20–32.

- Langdridge D. Phenomenological psychology: theory, research and method. Harlow: Prentice Hall; 2007.

- Finlay L, Gough B. Reflexivity: a practical guide for researchers in health and social sciences. Malden (MA): Blackwell Science; 2003.

- Flick U. An introduction to qualitative research. Los Angeles: Sage; 2018.

- Kelley K, Clark B, Brown V, et al. Good practice in the conduct and reporting of survey research. Int J Qual Health Care. 2003;15(3):261–266.

- Kroll T, Barbour R, Harris J. Using focus groups in disability research. Qual Health Res. 2007;17(5):690–698.

- Clarke V, Braun V. Successful qualitative research: a practical guide for beginners. London: Sage; 2013.

- Starks H, Brown Trinidad S. Choose your method: a comparison of phenomenology, discourse analysis, and grounded theory. Qual Health Res. 2007;17(10):1372–1380.

- Creswell JW. Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five traditions. Thousand oaks (CA), London: Sage Publications; 1998.

- Harper D. Talking about pictures: a case for photo elicitation. Visual Stud. 2002;17(1):13–26.

- Braun V, Clarke V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual Res Psychol. 2021;18(3):328–352.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

- Shenton AK. Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. EFI. 2004;22(2):63–75.

- Carpenter C, Suto MJ, editors. Qualitative research for occupational and physical therapists: a practical guide. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons. 2008.

- Zhang G, Poulsen DV, Lygum VL, et al. Health-Promoting nature access for people with mobility impairments: a systematic review. IJERPH. 2017;14(7):703.

- Lundberg NR, Taniguchi S, McCormick BP, et al. Identity negotiating: redefining stigmatized identities through adaptive sports and recreation participation among individuals with a disability. J Leisure Res. 2011;43(2):205–225.

- McMillen A-M, Söderberg S. Disabled persons’ experience of dependence on assistive devices. Scand J Occup Ther. 2002;9(4):176–183.

- Parette P, Scherer M. Assistive technology use and stigma. Educ Train Develop Disab. 2004;39(3):217–226.

- Murray CD, Forshaw MJ. The experience of amputation and prosthesis use for adults: a metasynthesis. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35(14):1133–1142.

- Desmond D, Layton N, Bentley J, et al. Assistive technology and people: a position paper from the first global research, innovation and education on assistive technology (GREAT) summit. Disab Rehabil Assist Technol. 2018;13(5):437–444.

- Hocking C. Function or feelings: factors in abandonment of assistive devices. TAD. 1999;11(1-2):3–11.

- Santana-Santana SB, Peña-Alonso C, Espino P-C. E. Assessing universal accessibility in spanish beaches. Ocean Coast Manage. 2021;201:105486.

- Sk N-J, Kim K-B, Oh C. Beaches for everyone? Marine tourism for mobility impaired visitors in Busan. Korea J Coast Res. 2021;114(sp1):375–379.

- Waldron D, Layton N. Hard and soft assistive technologies: defining roles for clinicians. Aust Occup Ther J. 2008;55(1):61–64.