ABSTRACT

The watchdog role is central to the democratic legitimacy of journalism and is also perceived as an essential part of journalists’ role performance by the public. So far, the expectations on journalists’ watchdog role performance have been studied as a static concept resulting in limited knowledge of the underlying dynamics in audience demand and expectations for this type of journalism. We argue that the demand for watchdog journalism is dynamic and varies according to changes in the broader context and across audience characteristics. We take a multi-method approach to examine the demand for watchdog journalism during the COVID-19 pandemic in Denmark. First, we use data from three representative surveys (n≈1.000 in each), including a panel component (n = 336), to demonstrate that the demand for watchdog journalism increased over time, especially among opposition voters, as the political context offered more political conflict and contested policy solutions. Second, a qualitative analysis of answers to an open-ended question in the surveys examines how the audience believes the watchdog role should be performed. We show that the demand for different functions of journalists’ critical reporting varies over time and that the form used by journalists when conducting critical reporting is extremely important to the audience.

The role as the watchdogs of society is one of the most prominent ideals for professional journalists (Deuze Citation2005). By exposing wrongdoings and asking critical questions, journalists scrutinize those in power and hold them accountable to the broader public (Norris Citation2014). Thus, the watchdog role is an essential part of the news media as a Fourth Estate, and it has positive externalities beyond individual audience gratifications (Nielsen Citation2016). For example, studies have demonstrated that politicians are less likely to engage in malpractices when the press has a strong presence in their community (Adserà, Boix, and Payne Citation2003; Rubado and Jennings Citation2020; Snyder and Strömberg Citation2010).

Research on journalists’ role perceptions has repeatedly demonstrated strong support for the watchdog ideal, particularly among journalists in well-established democracies (e.g., Hanitzsch Citation2011; Hanitzsch et al. Citation2019; Weaver and Willnat Citation2012). However, other studies have analysed actual journalistic content and demonstrated a considerable gap between journalists’ role perceptions and their role performance, or in other words between what they believe to be important in their role as journalists and what they actually do (Mellado et al. Citation2020; Mellado and van Dalen Citation2014).

Studying how journalists themselves believe they must fulfil certain professional roles to serve the public and how these role perceptions translate into news content only reflects considerations on the supply side of journalism. So far, research within journalism has paid limited attention to the demand side and the expectations from the very same public that journalists claim to serve (Karlsson and Clerwall Citation2019) and especially to the dynamics of these expectations. These audience expectations on journalists are particularly important because journalistic role perceptions have been defined as “generalized expectations which journalists believe exist in society and among different stakeholders, which they see as normatively acceptable, and which influence their behavior on the job” (Donsbach Citation2012, 1).

Given the journalistic creed to serve the public interest, citizens can be considered crucial stakeholders, and they have only become increasingly important during what has been coined the “audience turn” in journalism from the 1990s and onwards (Costera Meijer Citation2020). In other words, audience expectations serve as an important foundation for journalists’ role perceptions. Through much easier access to feedback from the audience via various audience metrics, expectations on the demand side have become increasingly visible and critical to journalists—not only to retain a sufficiently large audience but also to retain legitimacy by meeting the expectations of the audience in their role performance (Skovsgaard and Bro Citation2011). Thus, exploring audience demand for watchdog journalism and expectations regarding how journalists should perform the critical watchdog role are crucial aspects of understanding the legitimacy of journalism in a rapidly changing media environment, where people can easily avoid professionally produced news or access content from alternative news outlets if they find mainstream news irrelevant (Palmer, Toff, and Nielsen Citation2020).

There are existing studies that map audience expectations towards journalism. They show that the audience, in general, perceives the critical watchdog to be an important role for journalists (e.g., Gibson et al. Citation2022; Loosen, Reimer, and Hölig Citation2020; Riedl and Eberl Citation2022; Vos, Eichholz, and Karaliova Citation2019; Willnat, Weaver, and Wilhoit Citation2019). While these studies provide valuable insight into the role of watchdog reporting as an important factor in the legitimacy of journalism, they treat these expectations as a static phenomenon. They do not consider the dynamic nature of contextual factors, such as the political and societal environment, in which these expectations are developed and updated. In other words, we know that audiences find the watchdog role important, but we do not know under which conditions the role is seen as more or less important and how the audience believes it should be performed in different contexts.

We argue that to capture and explain variation in audience demand for journalists’ critical watchdog role performance, variations in the broader context must be considered along with individual predispositions and the interaction between the two. To explore this argument, we draw on a multi-method design. First, we examine variations in the demand for watchdog journalism over time using three representative surveys of the Danish population (N≈1.000 in each), including a panel component (N = 336), collected during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021.

Because of the highly dynamic nature with varying degrees of uncertainty among the public and varying degrees of political contestation, the COVID-19 pandemic is a well-suited case to study whether considerable variation in the political context comes with changes in the demand for and expectations towards critical watchdog journalism. Furthermore, with the political nature of the decisions during the crisis, the pandemic is also a well-suited case to analyse the impact of individual political predispositions and more importantly their interaction between these predispositions and the contextual factors on audience demand for watchdog journalism.

Second, while demand is connected to the emphasis that the audience believes should be put on watchdog role performance, the COVID-19 pandemic is also a well-suited case to explore audience expectations on how journalists should perform the critical watchdog role in varying contexts. We do this through a qualitative analysis of responses to an open-ended question on how audiences expect journalists to perform in this context. The qualitative approach adds a deeper and more fine-grained understanding of audience expectations towards journalists’ performance of the watchdog role in varying contexts. Despite the suitability for studying variations in the demand for watchdog journalism and the expectations toward how the role should be performed, the COVID-19 pandemic case also comes with limitations in terms of generalizability, which we discuss in the concluding section.

The Watchdog Role and Journalistic Legitimacy

Providing citizens with the information they need to be free and self-governing is journalism’s main claim to legitimacy (e.g., Kovach and Rosenstiel Citation2001; Skovsgaard and Bro Citation2011). While the commitment to serving the public is a fundamental part of the professional journalistic ideology (Deuze Citation2005), different conceptions of democracy lead to different normative expectations on how journalists should serve the public (Strömbäck Citation2005). Thus, journalists can claim legitimacy through articulating and enacting different roles (Hanitzsch and Vos Citation2017), such as informing the public of the actions of elite actors, including citizens to facilitate public debate, or mobilizing citizens to political participation (e.g., Bro Citation2008).

One of the most prominent journalistic role perceptions is the watchdog role. Watchdog journalism can be defined as (1) the independent scrutiny by the press of the activities of government, business, and other public institutions with the aim of (2) documenting, questioning, and investigating those activities to (3) provide publics and officials with timely information on issues of public concern (Bennett and Serrin Citation2005, 396). When journalists investigate and challenge those in power, it deters them from abusing their power and at the same time ensures that the public is more thoroughly informed, as those in power must explain the merits of their positions and decisions (Norris Citation2014). Research on journalists, particularly in well-established democracies, has demonstrated strong support for the watchdog role as a central aspect of their claim to professional legitimacy (e.g., Hanitzsch Citation2011; Hanitzsch et al. Citation2019; Weaver and Willnat Citation2012).

The role performance literature has added to this research field by exploring the central question of how these role perceptions translate into news content (e.g., Mellado Citation2019; Mellado and van Dalen Citation2014; Mellado, Hellmueller, and Donsbach Citation2017). Studies on how journalists perform the watchdog role have demonstrated a considerable gap between journalists’ own role perception and their role performance as measured in actual content, indicating that journalists’ own role perceptions might not always align with their performance (e.g., Mellado et al. Citation2020; Mellado and van Dalen Citation2014).

These findings shed light on the supply side of journalism and illuminate how roles are perceived and performed by journalists as part of commanding legitimacy in their professional work (Hanitzsch and Vos Citation2017; Mellado et al. Citation2020). However, to understand how journalists can gain legitimacy through adhering to and performing certain professional roles, the focus on the supply side of journalism must be complemented by a focus on the demand side. While quality journalism used to be an internal issue where journalists showed little regard for the audience (e.g., Gans Citation1980), the last couple of decades have witnessed a so-called “audience turn” in journalism (Costera Meijer Citation2020). Central in the “audience turn” is the digitalization of news and the omnipresence of audience metrics and measurements which have illuminated the importance of meeting audience demand and expectations to generate the necessary revenue for survival, but also for the legitimacy of news organizations that claim to serve the public by informing citizens (Costera Meijer Citation2020). Thus, understanding the legitimacy of journalists and their role performance requires a deeper understanding of public expectations on journalism (Swart et al. Citation2022), and in this case the prominent ideal of watchdog journalism.

A Context-Dependent Audience Demand for Watchdog Journalism

In line with the audience turn in journalism, some studies have shifted attention from the supply side to the demand side of journalism. These studies show varying public support for the watchdog role. In some studies, the watchdog role is at the very top among the different roles that journalists perform (e.g., van der Wurff and Schoenbach Citation2014; Willnat, Weaver, and Wilhoit Citation2019), but in other studies, several other journalistic roles rank higher (e.g., Loosen, Reimer, and Hölig Citation2020; Riedl and Eberl Citation2022; Tandoc, Jr and Duffy Citation2016; Vos, Eichholz, and Karaliova Citation2019).

Studies comparing public expectations on the roles of journalists to the role perceptions of journalists themselves also show varying results. In two of the studies making the comparison, journalists show more support for the watchdog role than the public (Vos, Eichholz, and Karaliova Citation2019; Willnat, Weaver, and Wilhoit Citation2019), while in two other studies, the public shows more support than the journalists (Loosen, Reimer, and Hölig Citation2020; Riedl and Eberl Citation2022). These studies have been conducted in different countries on different samples at different points in time, and they are all based on cross-sectional data. Therefore, they do not explore developments in the public demand for watchdog journalism over time. The mixed results give an indication, however, that the demand for watchdog journalism is likely to be dynamic and dependent on the broader context within which it is situated.

While a host of different contextual factors at the societal level might impact the demand for journalists’ role performance, we focus on the potential impact of the political context because the watchdog role is closely tied to the scrutiny of the powerful elites. Recent research on journalistic role performance has demonstrated that political context influences journalists’ performance of the watchdog role. One study shows that in countries with higher scores on the V-Dem Liberal Democracy index journalists perform the watchdog role to a higher degree than in countries with a lower score (Mellado et al. Citation2024). Another study demonstrates that when covering the COVID-19 pandemic journalists performed the watchdog role less than in other news content, indicating that the political context of the pandemic impacted journalists’ role performance (Hallin et al. Citation2023).

Earlier research focused on audience demand and news consumption patterns rather than journalists’ role performance has also demonstrated that the political context is an important factor. By comparing how hard news stories are prioritized by journalists with how much they are consumed by the audience, Boczkowski and Mitchelstein (Citation2010) find that journalists select and prioritize hard news stories substantively more than consumers do in times with normal political activity. However, in periods with intense political activity, i.e., changes in the political context, this gap decreases or disappears. We draw on this logic to argue that public demand for and expectations towards journalists’ watchdog role performance is likely to also vary with variations in the political context. Several aspects of the political context might impact audience expectations on journalists’ watchdog role performance, but in the case description below we focus on over-time variations in political contestation, trust in government (those in power), and uncertainty about the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic.

While we can expect the public demand for and expectations towards watchdog journalism to vary with the political context, individual differences are also likely to play a role. The studies that do explore the impact of individual factors on expectations on journalists’ role performance indicate that political ideology explains variation in the expectations of watchdog journalism (Riedl and Eberl Citation2022; Willnat, Weaver, and Wilhoit Citation2019). We build on these results to explore not only whether political ideology explains variation in the expectations of watchdog journalism, but also whether political ideology interacts with the political context in explaining variations in public expectations of watchdog journalism. That is, whether changes in the political context will have larger effects for people with a specific political leaning than for people with another political leaning. This examination will add to our understanding of the combination of contextual and individual level drivers of (changes in) public demand for watchdog journalism.

In addition to exploring under which conditions the demand for watchdog journalism varies, it is also important to explore how the audience expects journalists to perform the watchdog role and whether that also varies depending on the circumstances provided by the context (e.g., Hariman Citation1992). Studies of coverage of trauma and terror have shown that journalists are aware of the context-sensitive expectations towards their role performance in reporting crisis issues, including the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., Jukes, Fowler-Watt, and Rees Citation2022; Kay et al. Citation2011; Konow-Lund, Hågvar, and Olsson Citation2019; Vobic Citation2022). As these expectations can span across several aspects, such as form, ethics, transparency, and objectivity, we take an open approach in the exploration of the how-question, which allows for the respondents to address the aspects that they find most important and allows us to explore how this might vary across different contexts.

Case and Expectations

To examine our argument for context-dependent demand for watchdog journalism, we use the case of Denmark during the COVID-19 pandemic. This is a well-suited case because it enables us to link specific variations in the context to the demand for watchdog journalism in a confined period, while other factors, such as the parties in government and opposition, remain stable. Compared with most other countries, Denmark has high social and institutional trust (Our World in Data Citationn.d.) and a relatively low level of affective polarization among citizens (Gidron, Adams, and Horne Citation2019). These tendencies are also reflected in the media system which is characterized by comparatively high levels of trust in the press and news, strong public service media, a relatively low level of perceived polarization among media outlets, and a comparatively low level of news avoidance (Newman et al. Citation2022; Citation2023). Danish journalists also strongly adhere to the watchdog role and are committed to holding those in power to account compared to most other countries (Hanitzsch et al. Citation2019; Skovsgaard et al. Citation2012).

During the Covid-19 pandemic, 90 percent of Danish citizens claimed to have high or moderate trust in the country’s health authorities, and they showed a high willingness to be vaccinated (Adler-Nissen, Lehmann, and Roepstorff Citation2021). Curfews were not applied, and behavioural changes were mostly accomplished through widely accepted recommendations from health authorities, rather than laws. Likewise, temporary lockdowns happened without great criticism. Therefore, Denmark can be seen as a least-likely case for high demand for watchdog journalism because the public at large showed relatively low discontent with authorities despite many decisions with wide-ranging consequences for the ordinary citizen. If the political context in combination with individual political predispositions, as outlined below, influence the expectations of watchdog journalism in this case, we will likely find them in less trusting and more polarized societies as well. The least-likely case design makes a stronger argument for possible generalizations beyond the case of COVID-19, but of course, the case also comes with some limitations that we will address in the concluding discussion.

As mentioned above, the high levels of trust and the sense of community in Denmark made COVID-19 policy-making easier than in many other countries. Despite the successful overall handling of the crisis, there was especially one episode during the pandemic that dented public trust in authorities. Research shows that the most significant drop in Danes’ trust in government happened shortly after an event termed “Minkgate” (Adler-Nissen, Lehmann, and Roepstorff Citation2021). In early November 2020, the Prime Minister announced that all minks in Denmark were to be killed to avoid the spread of a coronavirus mutation. Within two weeks, approximately 11 million minks were killed, and an industry was de facto terminated. Afterwards, it turned out that the government did not have the legal authority to make such a wide-ranging decree. Due to this scandal, the Minister for Food, Agriculture, and Fisheries resigned, and a public investigation was initiated. Although Danes’ trust in the government increased since this episode, it did not fully recover (Adler-Nissen, Lehmann, and Roepstorff Citation2021).

We approach the COVID-19 pandemic through the lens of Down’s issue attention cycle (Citation1972) and argue that the crises can be divided into three phases. After the pre-problem phase, the problem emerges in public awareness. In this first phase, a crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic with enormous potential consequences for society not only leads people to consume more news to learn more and mitigate the uncertainty (e.g., Althaus Citation2002; Liu, Fraustino, and Jin Citation2016, 627), it also inclines the news media to focus more on helping the community experiencing the trauma (Gutsche and Salkin Citation2016). This initial phase is also generally characterized by high support for the incumbent politicians, the so-called “rally-around-the-flag effect” (Johansson, Hopmann, and Shehata Citation2021), which can be expected to reduce the popular demand for watchdog journalism. After the initial phase, in a second phase, the rally-around-the-flag effect fades (ibid), and political conflict lines on, for instance, the consequences of lockdowns and restrictions on individual rights begin to emerge. As citizens take cues from the politicians that they usually support (Druckman, Peterson, and Slothuus Citation2013), we can expect that the demand for critical watchdog journalism (often scrutinizing incumbent politicians) will increase, particularly among the ones supporting opposition parties. In the third phase, the intensity of the crisis is reduced, and controversial political decisions are being phased out (Downs Citation1972). In this phase, we expect that the demand for watchdog journalism will find an equilibrium between the initial phase with low demand for watchdog journalism and the second phase with a high demand for watchdog journalism. We still expect to find differences between supporters of the government and supporters of the opposition parties.

Based on the variations in the context outlined above and the possible interaction with individual predispositions, our study is guided by the following main research question:

RQ: How does audience demand for watchdog journalism and the expectations towards journalists’ watchdog role performance vary in different phases of the COVID-19 crisis?

H1: As the initial phase is characterized by high support for the incumbent politicians, the so-called rally-around-the-flag effect, audience demand for watchdog journalism is low.

H2: As the second phase is characterized by increasing political conflict, the demand for watchdog journalism (often scrutinizing incumbent politicians) increases.

H3: The third phase will be characterized by an equilibrium between the initial phase with a low demand for watchdog journalism and the second phase with a high demand for watchdog journalism.

H4: The increase in demand for watchdog journalism will be particularly pronounced among supporters of opposition parties.

Methods

Data and Analyses

To explore our research question and hypotheses we draw on a mixed methods design based on data from three representative surveys with a panel component. The surveys include close-ended as well as an open-ended question on audience expectations on and evaluations of journalism in relation to the COVID-19 crisis and were collected in collaboration with the private company Norstat. The first survey was conducted 4–7 April 2020 (n = 1,041, response rate = 17%), the second 10–16 November 2020 (n = 1,000, response rate = 14%), and the third 3–14 June 2021 (n = 1,000, response rate = 12%), with each data collection reflecting the above-mentioned three phases in the COVID-19 crisis. The samples were drawn from an online panel and stratified to reflect the Danish population above 18 years old on gender, age, education, and geographical region. Subsequently, the data was weighted on the same parameters to obtain more precise descriptive estimates. In addition, respondents participating in the first survey were also reinvited to participate in the second and third survey providing a panel component (n = 336) enabling us to analyse within-person variation over time. Despite the low number of respondents participating in all three survey waves and a slight tendency towards higher mean age and more males than in the full, representative samples, this setup provides us with a better understanding of the over-time dynamics in audience expectations and whether changes in the context have different impact for different individuals.

The demand for watchdog journalism is operationalized with two questions. First, to understand changes in the priority given to the watchdog role performance over time, we asked the respondents to choose what they saw as the most important task for journalism in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic. Even though demand for different roles is not mutually exclusive, respondents were asked to choose one of the following tasks in order to know which role was given highest priority: “Ask critical questions and challenge politicians and authorities”; “Inform about the consequences that decisions made by authorities and politicians have for ordinary people”; “Puncturing myths, conspiracy theories and fake news”; “Tell that there is hope and solutions”; “Involve Danes by forwarding their questions to experts”; “Provide analyses and perspectives”; “Another task”.

Second, we asked the respondents whether they thought that journalists had put “Way too much weight”, “Too much weight” “Neither too much nor too little weight”, “Too little weight”, or “Way too little weight” on asking critical questions and challenge politicians and authorities. This question also included a “Don’t know” category.

To examine how individual political predispositions influence the demand for watchdog journalism, we also asked respondents which party they would vote for, if a national election was held the following day. Subsequently, the respondents were divided into three groups reflecting whether they voted for the government (The Social Democrats), supporting parties (Danish Social Liberal Party, Green Left, and The Red-Green Alliance), or the opposition (Venstre—The Liberal Party of Denmark, Danish People’s Party, Liberal Alliance, The Conservative People's Party, and The New Right). This question was only included in the second and third survey. For the panel analysis, we therefore only include those respondents (n = 201) that did not change their group affiliation in the last two survey waves and assume that they belong to this group in the first survey wave as well.Footnote1

The qualitative data come from respondents’ answers to the open-ended reflective question: “In your own words, try to describe what role you think is most important for Danish journalists to play during a crisis such as the corona pandemic and why. Please describe your position as thoroughly as possible”. In total, 456 valid individual answers were provided over the three survey waves (answers such as “I don’t know”, “I pass”, and “?” were excluded). The coding of the data corpus was undertaken by two student assistants and one of the authors who identified the responses on role performance. Based on an explorative approach, a coding list was developed through several iterations to arrive at a satisfactorily consistent way of coding. The coding process consisted of two steps. First, the data were inductively grouped into coding units that expressed similar ideas or actions. Second, by reviewing the extracted data corpus in each unit a definition for each set of grouped coding units was developed. The explorative analysis of the open-ended data was based on principles of qualitative data analysis (Boyatzis Citation1998), and it resulted in the themes presented in the analysis section. Original Danish wording of the presented quotes can be found in the Appendix.

Context-dependent Audience Demand for Watchdog Journalism

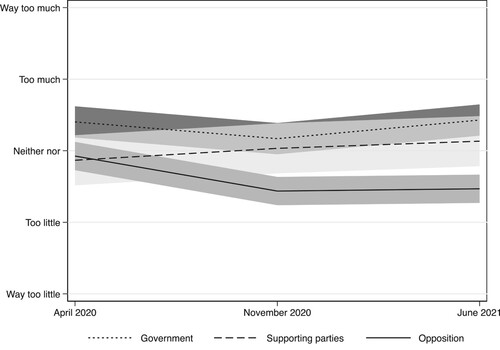

To examine our hypotheses, we first utilize the quantitative data to examine how the demand for different journalistic roles developed over time. illustrates the share of respondents indicating that the respective roles were the most important for journalists to fulfil during the COVID-19 crisis when asked to only choose the role that they give the highest priority. In the first phase of the pandemic in April 2020, the role most often chosen was “informing the public about consequences of decision made by authorities and politicians”. This role was chosen by 28 pct. in the first phase but dropped to 19.4 pct. in the second phase and 18.9 pct. in the third phase, in November 2020 and June 2021, respectively. These results do not necessarily reflect that informing the public of decisions made by authorities and politicians became unimportant to the audience but that priority for other roles increased.

Figure 1. Development in audience demand for journalistic roles over time.

Note. Displays share of respondents choosing each task as the most important one. n(April 2020) = 1,041, n(November 2020) = 1,000, n(June 2021) = 1,000.

While informing the public is important, the audience perceived it as increasingly important that journalists would employ a more critical approach to those in power when doing the reporting. This tendency is reflected in the results for the watchdog role. In April 2020, the demand for the critical watchdog role was relatively low at 16.8 pct. choosing this role as the most important. In November 2020 this share increased to 32.8 pct., before decreasing a bit to 29 pct. in June 2021. While these increases between the share in the first survey and the shares in the two subsequent waves are statistically significant (p <.001), the decrease between the shares in the second and third waves is not statistically significant. These findings support our expectations that the audience demand for watchdog journalism is indeed context dependent. The demand was low in the initial phase (H1) while it increased in the second phase (H2) before finding a level closer to equilibrium in the third phase (H3).

Variation in the Demand for Watchdog Journalism Across Political Affiliation

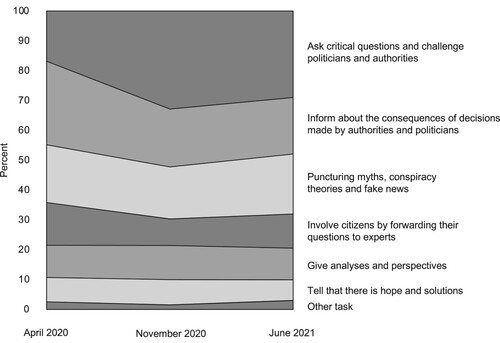

To explore how these dynamics in the audience demand for watchdog journalism might be conditioned on people’s political affiliation, we included party preference in the analysis. As seen in , the demands for watchdog journalism in November 2020 and June 2021 were clearly dependent on party preference. In November 2020, 20.3 pct. of those voting for the government thought that journalists gave too little weight to asking critical questions and challenging politicians and authorities, while this applied to 29.5 pct. of voters for supporting parties and 43.7 pct. of the opposition voters. In June 2021, 16.6 pct. of those voting for the government thought that gave too little weight to the task, while the same applied to 27.3 pct. of voters for supporting parties and 37.1 pct. of opposition voters.

Figure 2. Views across party preference on the weight journalists gave to asking critical questions and challenge politicians and authorities.

Note. November 2020: n(government) = 256, n(supporting parties) = 155, n(opposition) = 340. June 2021: n(government) = 239, n(supporting parties) = 145, n(opposition) = 320.

Looking at those who thought that journalists gave too much weight to asking critical questions and challenge politicians and authorities, we likewise see that party preferences are important for the demand for watchdog journalism. In November 2020, 29.7 pct. of the government voters thought that journalists gave too much weight to this critical endeavour, while this was the case for 18.7 pct. of voters for the supporting parties and 13.2 pct. of opposition voters. In June 2021, 25.7 pct. of government voters thought that journalists gave too much weight to asking critical questions and challenging politicians and authorities, while the same was true for 19.8 pct. of voters for supporting parties and 15.6 pct. of opposition voters.

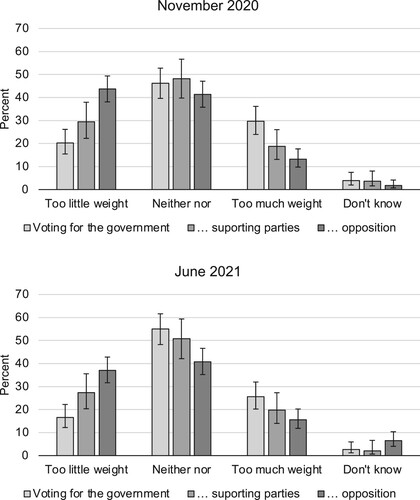

Although the three representative surveys provide a relatively precise picture of audience demand for watchdog journalism, we cannot be sure which audiences increased their demand for critical journalism over time, because we did not measure party affiliation in the first survey. To address this limitation, we turn to the panel component of our surveys to analyse how the demand for watchdog journalism varied among individuals over time. As seen in , there were no significant differences in demand for watchdog journalism across party affiliations in April 2020. Over time, however, the demand for watchdog journalism increased among opposition voters to a level that significantly differed from voters of the government and supporting parties, who displayed more stable demands. Taken together, the results support our expectation that the increase in demand for watchdog journalism is particularly pronounced among voters supporting opposition parties (H4).

How Journalists Should Perform the Watchdog Role

To gain a deeper understanding of audience expectations on how journalists should perform the watchdog role, we draw on the qualitative data collected in the open-ended questions in our surveys. In general, respondents agree that journalists should perform a critical and probing watchdog journalism, and they accept that journalists use their reporting to probe and challenge politicians and authorities to explain, reflect, argue, document, and take responsibility. However, the data analysis also shows that audience acceptance of these types of reporting varies over time and that journalists should perform the watchdog role with particular care to communicate in a way that is acceptable in a phase of the crisis characterized by uncertainty. The audience is particularly preoccupied with two aspects of critical watchdog reporting practices: function and form.

Functions of Critical Journalistic Questioning

Respondents clearly express that they accept and expect watchdog reporting. In their opinion, journalists are supposed to be critical in their treatment of politicians and authorities, consistent with the ideal of the press as an independent watchdog counterbalancing official power. The normativity is evident since the respondents refer to this type of reporting as generally good, informative, and desirable for society.

Journalists should generally be more critical … and try to find out what is “fake or factual” instead of just throwing it into the media as sensationalism – which is what the “tabloids” in particular do. In doing so, they make us ordinary citizens unsafe and anxious. The job of journalists should be to inform us as well as possible so that we can take an informed position on the issue.

Female, 78, government supporter, April 2020

Investigate statements from politicians and officials to clarify what is true and what is politics. Describe the consequences of the various statements so that the ordinary citizen knows what is being said and why.

Male, 75, opposition supporter, June 2021

The second function that respondents are very concerned with is critical reporting used to challenge politicians and authorities.

Ask about the public administration and justification for the many initiatives. Be aware of the costs of the crisis on society, how the huge government loans will be repaid, and be more critical about the mistakes the government makes – again and again – including illegal measures, such as the mink slaughtering.

Male, 77, voting blank, June 2021

Respondents also address a supplementary function of critical reporting by addressing the perception that politicians and authorities were acting imperiously when making wide-ranging decisions.

There should be one role: 1) to focus on the disease control itself and the choices and actions of the authorities. But for this government, the journalists have yet another role: 2) the usurped power of the government at the expense of the people's rule and its pronounced reluctance to hand over power again.

Male, 69, opposition supporter, June 2021

Forms of Critical Reporting

The respondents express their discontent when journalists use a form of critical reporting characterized by nit-picking, aggression, and negativity.

Every time they find the smallest thing to criticize the government for, they blow it up into monstrous proportions instead of acting sensibly and balanced.

Female, 86, government supporter, June 2021

They must provide information and ask critical questions when necessary. But they don't need to subject people to a witch hunt.

Female, 54, undecided, June 2021

Some of the criticism levelled at journalists’ watchdog role performance is connected to the many press conferences and live interviews with politicians and authorities that were a prominent feature during the pandemic where information needs were high. At these live events, the public is directly exposed to how journalists pose their critical questions as part of their watchdog role performance, and some of the respondents address the deliberately negative and conflict-seeking way of asking questions.

They are welcome to drill a bit into answers and decisions, but not from a deliberately negative attitude. I would like to be informed and know something about the background of the decision and what can be expected, but I get annoyed if you are only out to create discord.

Female, 46, government supporter, June 2021

In these quotes, there is an underlying expectation about professional journalists being able to control themselves and act professionally by asking critical questions in a polite and respectful manner. Such questions should both challenge politicians and authorities but also give them a chance to answer constructively in a way that provides information about the background and their reasoning behind a political decision rather than just defending themselves.

Speak nicely but be very insistent when asking authority figures/politicians. Prepare their questions better through research and make them short and precise and not – as I think we sometimes experience – that it's just about hearing yourself and putting yourself in focus to get 15 minutes of fame.

Female, 58, unknown political affiliation, April 2020

I have missed, however, that the journalists have done their preparatory work by delving deeply themselves into the pandemic, and they have not been good at listening. At various press conferences, there have been many repetitive questions that had already been thoroughly answered.

Male, 24, unknown political affiliation, April 2020

Variations Over Time

In terms of variation over time, the qualitative data shows that audience acceptance is different in the initial phase of the crisis and the subsequent phases, but no differences between the second and third phases were found. Regardless of which phase respondents address, their (un)acceptance deals with either the function (the type of information) or the form (the approach the journalists use) in their critical watchdog reporting. In the second and third phases of the crisis, audience members emphasize the need for critical reporting in order to counteract imperious behaviour displayed by politicians and authorities. Thus, political decisions made with limited political deliberation as well as limited inclusion of opposing views lead the audience to increase the demand for watchdog journalism and show more acceptance of critically reporting on and asking adversarial questions to immediate political decisions. This point is reflected in the fact that countering the imperious behaviour of those in power is a theme that is only mentioned by respondents in later phases of the pandemic and not in the first wave of data collection.

However, in all three phases, respondents express discontent when journalists use a form in the critical reporting characterized by nit-picking, aggression, and negativity, and also if they apply a self-promoting style or repetitive questions in press conferences or live interviews. In the second and third phases, respondents additionally point out that journalists should avoid personal attacks and blowing things out of proportion while also expressing an increasing demand for journalists to be critical towards those in power. These variations in the demands and expectations of the watchdog role performance reflect that the demand for critical journalism is not unidimensional and universal across contexts.

Discussion and Conclusion

While the audience in general is known to value watchdog journalism and perceive this journalistic role as important (e.g., Loosen, Reimer, and Hölig Citation2020; Riedl and Eberl Citation2022; Vos, Eichholz, and Karaliova Citation2019; Willnat, Weaver, and Wilhoit Citation2019), we have limited knowledge of under which conditions it is seen as more or less important and how the audience thinks that the role should be performed in different contexts. In this study, we have argued that the demand for watchdog journalism does not only vary across audience characteristics but also with changes in the broader context. Using the case of the COVID-19 and the journalistic reporting of this crisis in Denmark, we have used a multi-method approach to show how the demand for watchdog journalism increased over time, especially among opposition voters, and that the expectations towards journalists’ role performance varied over time.

While most of the respondents were satisfied with the amount of watchdog journalism, answering that journalists had neither given too much or too little weight to this task, many also thought that this was not the case. Voters supporting the government tend to think that journalists had given too much weight to challenging politicians and authorities and asking critical questions. In contrast, opposition voters—apart from the initial phase of the pandemic which was characterized by uncertainty and low political conflict—tended to think that journalists had given too little weight to performing the watchdog role.

The qualitative analysis provided a deeper dive into the expectations of how journalists should perform the watchdog role. The audience acceptance of journalists’ critical reporting varied in different phases of the crisis, in a manner where the functions of adversarial reporting expand. Aditionally, the form applied by journalists in their critical reporting is an important factor because the audience clearly holds an aversion against nit-picking and overly negative reporting that do not allow politicians to respond and explain their perspective on an issue. This aligns with earlier research that also found that the audience dislike reporting and questioning that do not allow politicians to explain their views (Groot Kormelink and Costera Meijer Citation2017). Also, they criticize when journalists apply a self-promoting style or repetitive questions in the case of press conferences and live interviews where the audience are directly exposed to journalists’ critical questioning of elite sources. People rarely witness journalists perform this part of the watchdog role as it is usually a part of the research phase and not the reporting. When this form of reporting is applied, journalists risk ending up damaging their own and other journalists’ professional legitimacy rather than exposing the potential mistakes made by politicians or public figures which is the actual aim of watchdog reporting.

All in all, the results align with the development in the different phases of the COVID-19 crisis. The first phase, when the coronavirus emerged, was characterized by uncertainty (Shehata, Glogger, and Andersen Citation2021). Politicians and authorities made many decisions with profound consequences, and the most prominent demand from the audience was to be informed of these decisions and their consequences. As the uncertainty decreased and the attitudes towards the handling of the crisis got increasingly polarized, the audience demand for watchdog journalism increased. This development suggests that the rally-around-the-flag effects observed around the world during the COVID-19 pandemic (Baekgaard et al. Citation2020; Cardenal et al. Citation2021; Yam et al. Citation2020) also affected the demand for critical watchdog journalism. While people throughout the pandemic want to be informed about important decisions and their consequences through journalists’ reporting, they also expected journalists to take a more critical approach to those in power when informing the public after the initial high uncertainty decreased.

Recently, a striking perception gap regarding the watchdog role was revealed in interviews with so-called news avoiders. These news avoiders “did not subscribe to the watchdog ideal or believe that news media actually held power to account on behalf of the public”. Rather, “[t]hey saw news coverage about politics as relentlessly negative and pointless, with little connection to their lives” (Palmer, Toff, and Nielsen Citation2020, 1985). Such attitudes towards news can be seen as “a point of weakness” (ibid: 1986) in the relationship between journalists and their audience. Taking these considerations into account, this study demonstrates how the watchdog role is an essential task in audience demands for journalism, but that perceptions of when and how this journalistic role should be practiced vary both across audiences and over time. Thus, it is extremely important for journalists to engage in watchdog reporting, but when doing so they need to carefully consider the broader context and the specific functions this type of journalism fulfils. They should also carefully consider which forms are suitable when performing the watchdog role through critical reporting that challenges politicians and authorities. Otherwise, journalists end up undermining the legitimacy that watchdog journalism is supposed to generate and may even increase the likelihood of more people avoiding the news. This might also explain why a study found that when the audience members had stronger perceptions that journalists actually perform the watchdog role in their work, contrary to the authors’ expectations, it did not reduce the level of news avoidance (Kalogeropoulos, Toff, and Fletcher Citation2024). If journalists employ an overly aggressive form in their reporting, more watchdog role performance might even lead to more rather than less news avoidance.

The results from this study also add to the existing literature on journalists’ role performance. While the literature on role performance has added a crucial perspective to the extensive literature on journalistic role perceptions, less attention has been paid to the audience demand for and expectations of journalists’ role performance (Karlsson and Clerwall Citation2019), and even less to the explanations and dynamics in these demands and expectations. The role performance literature has advanced our understanding by highlight the ongoing process between how journalists perceive their roles in society, how they perform these roles in their daily work and translate it to news content (e.g., Mellado et al. Citation2020; Mellado and van Dalen Citation2014). In line with our argument on the significance of accounting for political context, studies in this literature have also demonstrated that the political context influence journalists’ role performance including the watchdog role (Hallin et al. Citation2023; Mellado et al. Citation2024).

We add to these insights with a closer look at how the audience evaluates journalistic role performance, and how context and individual predispositions in combination shape the demand for and expectations of journalists’ role performance.

The link to the audience demand and expectations is crucial given that journalistic role perceptions have been defined as “generalized expectations which journalists believe exist in society and among different stakeholders, which they see as normatively acceptable, and which influence their behavior on the job” (Donsbach Citation2012, 1). Thus, by adding the audience dynamic and context-dependent audience demand and expectations, this study aids the understanding of how journalists should dynamically interpret their own roles in society and perform them in their everyday work.

The study, of course, comes with some limitations. While the three representative surveys provided us with reliable estimates of the demand for watchdog journalism, the relatively low number of respondents in our panel analysis means that these results should not be generalized without care. Still, the panel analysis allows us to better capture over-time developments within individuals. Similarly, our qualitative analysis is limited by the relatively short answers provided to the open-ended question in the surveys. Longer, in-depth interviews had of course provided us with the opportunity to gain a more granular understanding of the audience perceptions of how journalists are expected to perform the watchdog role.

The case selection also has implications for the generalizability of the results. As our analysis was restricted to one country, namely Denmark, careful consideration must be given to how these results might generalize to other countries. As previously argued, Denmark, as a country with high institutional trust and limited criticism of lockdowns, serves as a least likely case for large variations in the demand for watchdog journalism. Thus, patterns like the ones observed in this study are highly likely to occur in other countries as well.

The COVID-19 pandemic, of course, is a special case as an extensive global crisis. However, while results might not generalize to other issues, similar mechanisms are likely at play in times with varying political contestation. Furthermore, health experts warn that in an increasingly globalized world pandemics are an increasing threat, and since it is still unclear if and how a climate catastrophe could be prevented, the next substantial crisis may be looming just over the horizon. Hence, the results of this study have implications that reach beyond the COVID-19 crisis, as they can be applied in the journalistic handling of other issues that are politically contested, and since they can assist journalists in considering their behaviour in future times of crisis.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The panel data consists of 336 respondents, of which 65 were excluded as they indicated in both waves 2 and 3 that they did not know who they would vote for or that they would not vote. Of the remaining 271 respondents, 69.7 percent voted for the same party in waves 2 and 3, while 8.5 percent changed party within either the coalition of supporting parties or the opposition coalition. 19.2 percent only indicated a specific party preference in one of the waves, while indicating that they did not know or that they would not vote in the other wave and were therefore excluded. 2.6 percent changed their vote between coalitions and were also excluded from the analysis. Lastly, 10 respondents were excluded as they had missing values on the dependent variables in one or more waves. In sum, 201 respondents were therefore included in the analysis. These respondents consist of more males (61 pct.) and are on average a bit older than the full samples.

References

- Adler-Nissen, R., S. Lehmann, and A. Roepstorff. 2021, November 14. “Denmark’s Hard Lessons About Trust and the Pandemic.” The New York Times https://www.nytimes.com/2021/11/14/opinion/denmark-trust-covid-vaccine.html.

- Adserà, A., C. Boix, and M. Payne. 2003. “Are You Being Served? Political Accountability and Quality of Government.” The Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization 19 (2): 445–490. https://doi.org/10.1093/jleo/ewg017.

- Althaus, S. L. 2002. “American News Consumption During Times of National Crisis.” PS: Political Science & Politics 35 (3): 517–521. https://doi.org/10.1017/S104909650200077X

- Baekgaard, M., J. Christensen, J. K. Madsen, and K. S. Mikkelsen. 2020. “Rallying Around the Flag in Times of COVID-19: Societal Lockdown and Trust in Democratic Institutions.” Journal of Behavioral Public Administration 3 (2): Article 2. https://doi.org/10.30636/jbpa.32.172.

- Bennett, W. L., and W. Serrin. 2005. “The Watchdog Role.” In The Press, edited by G. Overholser and K. H. Jamieson, 169–188. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Boczkowski, P. J., and E. Mitchelstein. 2010. “Is There a Gap Between the News Choices of Journalists and Consumers? A Relational and Dynamic Approach.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 15 (4): 420–440. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161210374646.

- Boyatzis, R. E. 1998. Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development. New York: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Bro, P. 2008. “Normative Navigation in the News Media.” Journalism 9 (3): 309–329. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884907089010.

- Cardenal, A. S., L. Castro, C. Schemer, J. Strömbäck, A. Steinska, C. de Vreese, and P. Van Aelst. 2021. “The Role of Polarization on Rally-Around-the-Flag Effects During the COVID-19 Crisis.” In Political Communication in Time of Coronavirus, edited by P. Van Aelst and J. G. Blumler, 157–173. London: Routledge.

- Costera Meijer, I. 2020. “Understanding the Audience Turn in Journalism: From Quality Discourse to Innovation Discourse as Anchoring Practices 1995–2020.” Journalism Studies 21 (16): 2326–2342. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2020.1847681.

- Deuze, M. 2005. “What is Journalism?: Professional Identity and Ideology of Journalists Reconsidered.” Journalism 6 (4): 442–464. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884905056815.

- Donsbach, W. 2012. “Journalists’ Role Perception.” In The International Encyclopedia of Communication, edited by W. Donsbach, 1–6. Malden, Massachusetts: Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405186407.wbiecj010.pub2.

- Downs, A. 1972. “Up and Down with Ecology-the Issue-Attention Cycle.” The Public Interest 28: 38–50.

- Druckman, J. N., E. Peterson, and R. Slothuus. 2013. “How Elite Partisan Polarization Affects Public Opinion Formation.” The American Political Science Review 107 (1): 57–79. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055412000500.

- Gans, H. J. 1980. Deciding What’s News: A Study of CBS Evening News, NBC Nightly News, Newsweek, and Time. New York: Vintage Books.

- Gibson, H., L. Kirkconnell-Kawana, E. Procter, J. Firmstone, and J. Steel. 2022. News Literacy Report: Lessons in Building Public Confidence and Trust. London: Impress.

- Gidron, N., J. Adams, and W. Horne. 2019. “Toward a Comparative Research Agenda on Affective Polarization in Mass Publics.” APSA Comparative Politics Newsletter 29: 30–36. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3391062.

- Groot Kormelink, T., and I. Costera Meijer. 2017. ““It’s Catchy, but It Gets You F*Cking Nowhere”: What Viewers of Current Affairs Experience as Captivating Political Information.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 22 (2): 143–162. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161217690881.

- Gutsche, R. E., and E. Salkin. 2016. “Who Lost What? An Analysis of Myth, Loss, and Proximity in News Coverage of the Steubenville Rape.” Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism 17 (4): 456–473. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884914566195

- Hallin, D. C., C. Mellado, A. Cohen, N. Hubé, D. Nolan, G. Szabó, Y. Abuali, … N. Ybáñez. 2023. “Journalistic Role Performance in Times of COVID.” Journalism Studies 24(16) (16): 1977–1998. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2023.2274584.

- Hanitzsch, T. 2011. “Populist Disseminators, Detached Watchdogs, Critical Change Agents and Opportunist Facilitators: Professional Milieus, the Journalistic Field and Autonomy in 18 Countries.” International Communication Gazette 73 (6): 477–494. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048511412279.

- Hanitzsch, T., F. Hanusch, J. Ramaprasad, and A. de Beer, (Eds). 2019. Worlds of Journalism: Journalistic Cultures Around the Globe. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Hanitzsch, T., and T. P. Vos. 2017. “Journalistic Roles and the Struggle Over Institutional Identity: The Discursive Constitution of Journalism.” Communication Theory 27 (2): 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1111/comt.12112.

- Hariman, R. 1992. “Decorum, Power, and the Courtly Style.” Quarterly Journal of Speech 78 (2): 149–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/00335639209383987.

- Johansson, B., D. N. Hopmann, and A. Shehata. 2021. “When the Rally-Around-the-Flag Effect Disappears, or: When the COVID-19 Pandemic Becomes ‘Normalized’.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 31 (sup1): 321–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457289.2021.1924742.

- Jukes, S., K. Fowler-Watt, and G. Rees. 2022. “Reporting the Covid-19 Pandemic: Trauma on Our Own Doorstep.” Digital Journalism 10 (6): 997–1014. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2021.1965489.

- Kalogeropoulos, A., B. Toff, and R. Fletcher. 2024. “The Watchdog Press in the Doghouse: A Comparative Study of Attitudes About Accountability Journalism, Trust in News, and News Avoidance.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 29 (2): 485–506. https://doi.org/10.1177/19401612221112572.

- Karlsson, M., and C. Clerwall. 2019. “Cornerstones in Journalism.” Journalism Studies 20 (8): 1184–1199. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2018.1499436.

- Kay, L., R. C. Reilly, E. Amend, and T. Kyle. 2011. “BETWEEN A ROCK AND A HARD PLACE: The Challenges of Reporting About Trauma and the Value of Reflective Practice for Journalists.” Journalism Studies 12 (4): 440–455. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2010.506054.

- Konow-Lund, M., Y. B. Hågvar, and E.-K. Olsson. 2019. “Digital Innovation During Terror and Crises.” Digital Journalism 7 (7): 952–971. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2018.1493937.

- Kovach, B., and T. Rosenstiel. 2001. The Elements of Journalism: What News People Should Know and the Public Should Expect. New York: Three Rivers Press.

- Liu, B. F., L. D. Fraustino, and Y. Jin. 2016. “Social Media Use During Disasters: How Information Form and Source Influence Intended Behavioral Responses.” Communication Research 43 (5): 626–646. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650214565917

- Loosen, W., J. Reimer, and S. Hölig. 2020. “What Journalists Want and What They Ought to Do (In)Congruences Between Journalists’ Role Conceptions and Audiences’.” Expectations, Journalism Studies 21 (12): 1744–1774. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2020.1790026.

- Mellado, C. 2019. “Journalists’ Professional Roles and Role Performance.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication 1–21. https://oxfordre.com/communication/view/10.1093acrefore/9780190228613.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228613-e-832.

- Mellado, C., D. C. Hallin, N. Blanchett, M. Márquez-Ramírez, D. Jackson, A. Stępińska, T. Skjerdal, … V. Wyss. 2024. “The Societal Context of Professional Practice: Examining the Impact of Politics and Economics on Journalistic Role Performance Across 37 Countries.” Journalism Online First, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/14648849241229951.

- Mellado, C., L. Hellmueller, and W. Donsbach, Eds. 2017. Journalistic Role Performance. Concepts, Contexts, and Methods. New York: Routledge.

- Mellado, C., C. Mothes, D. C. Hallin, M. L. Humanes, M. Lauber, J. Mick, H. Silke, et al. 2020. “Investigating the Gap Between Newspaper Journalists’ Role Conceptions and Role Performance in Nine European, Asian, and Latin American Countries.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 25 (4): 552–575. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161220910106

- Mellado, C., and A. van Dalen. 2014. “Between Rhetoric and Practice. Explaining the gap Between Role Conception and Performance in Journalism.” Journalism Studies 15 (6): 859–878. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2013.838046

- Newman, N., R. Fletcher, C. T. Robertson, K. Eddy, and R. K. Nielsen. 2022. Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2022. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2022-06/Digital_News-Report_2022.pdf.

- Newman, N., R. Fletcher, C. T. Robertson, K. Eddy, and R. K. Nielsen. 2023. Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2023. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2023-06/Digital_News_Report_2023.pdf.

- Nielsen, R. K. 2016. “The Business of News.” In The SAGE Handbook of Digital Journalism, edited by T. Witschge, C. W. Anderson, N. Domingo, and A. Hermida, 51–67. New York: SAGE Publications.

- Norris, P. 2014. “Watchdog Journalism.” In The Oxford Handbook of Public Accountability, edited by M. Edited by Bovens, R. E. Goodin, and T. Schillemans, 525–541. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Our World in Data. n.d. Trust. Retrieved 01 February 2024, from https://ourworldindata.org/trust.

- Palmer, R., B. Toff, and R. K. Nielsen. 2020. “The Media Covers Up a Lot of Things”: Watchdog Ideals Meet Folk Theories of Journalism.” Journalism Studies 21 (14): 1973–1989. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2020.1808516.

- Riedl, A., and J.-M. Eberl. 2022. “Audience Expectations of Journalism: What’s Politics got to do with it?” Journalism 23 (8): 1682–1699. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884920976422.

- Rubado, M. E., and J. T. Jennings. 2020. “Political Consequences of the Endangered Local Watchdog: Newspaper Decline and Mayoral Elections in the United States.” Urban Affairs Review 56 (5): 1327–1356. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087419838058.

- Shehata, A., I. Glogger, and K. Andersen. 2021. “The Swedish Way: How Ideology and Media use Influenced the Formation, Maintenance and Change of Beliefs About the Coronavirus.” In Political Communication in the Time of Coronavirus, edited by P. Van Aelst and J. Blumler, 209–223. New York: Routledge.

- Skovsgaard, M., E. Albæk, P. Bro, and C. H. de Vreese. 2012. “Media Professionals or Organizational Marionettes: Professional Values and Constraints of Danish Journalists.” In The Global Journalist in the 21st Century, edited by D. H. Weaver and L. Willnat, 155–170. New York: Routledge.

- Skovsgaard, M., and P. Bro. 2011. “Preference, Principle and Practice: Journalistic Claims for Legitimacy.” Journalism Practice 5 (3): 319–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2010.542066

- Snyder, J. M., and D. Strömberg. 2010. “Press Coverage and Political Accountability.” Journal of Political Economy 118 (2): 355–408. https://doi.org/10.1086/652903.

- Strömbäck, J. 2005. “In Search of a Standard: Four Models of Democracy and Their Normative Implications for Journalism.” Journalism Studies 6 (3): 331–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616700500131950.

- Swart, J., T. Groot Kormelink, I. Costera Meijer, and M. Broersma. 2022. “Advancing a Radical Audience Turn in Journalism. Fundamental Dilemmas for Journalism Studies.” Digital Journalism 10 (1): 8–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2021.2024764.

- Tandoc, Jr, E., and A. Duffy. 2016. “Keeping Up With the Audiences: Journalistic Role Expectations in Singapore.” International Journal of Communication 10: 3338–3358.

- van der Wurff, R., and K. Schoenbach. 2014. “Civic and Citizen Demands of News Media and Journalists: What Does the Audience Expect from Good Journalism?” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 91 (3): 433–451. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699014538974.

- Vobic, I. 2022. “Window, Watchdog, Inspector: The Eclecticism of Journalistic Roles During the COVID-19 Lockdown.” Journalism Studies 23 (5-6): 650–668. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2021.1977167.

- Vos, T. P., M. Eichholz, and T. Karaliova. 2019. “Audiences and Journalistic Capital. Roles of Journalism.” Journalism Studies 20 (7): 1009–1027. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2018.1477551

- Weaver, D. H., and L. Willnat. 2012. The Global Journalist in the 21st Century. New York: Routledge.

- Willnat, L., D. H. Weaver, and G. C. Wilhoit. 2019. “The American Journalist in the Digital Age.” Journalism Studies 20 (3): 423–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2017.1387071.

- Yam, K. C., J. C. Jackson, C. M. Barnes, J. Lau, X. Qin, and H. Y. Lee. 2020. “The Rise of COVID-19 Cases is Associated with Support for World Leaders.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117 (41): 25429–25433. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2009252117

Appendix

Table A1. Original quotes and translations