ABSTRACT

Purpose: To investigate how individual and environmental factors relate to self-reported participation profiles in adolescents with and without impairments or long-term health conditions. Methods: A person-oriented approach (hierarchical cluster analysis) was used to identify cluster groups of individuals sharing participation patterns in the outcome variables frequency perceived importance in domestic life and peer relations. Cluster groups were compared using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Results: A nine-cluster solution was chosen. All clusters included adolescents with impairment and long-term health conditions. Perceived importance of peer relations was more important than frequent attendance in domestic-life activities. Frequency of participation in dialogues and family interaction patterns seemed to affect the participation profiles more than factors related to body functions. Conclusion: Type of impairment or long-term health condition is a weaker determinant of membership in clusters depicting frequency and perceived importance in domestic life or peer relations than dialogue and family environment.

Introduction

Children’s mental health can be described either as lack of symptoms or as positive functioning in everyday life.Citation1 Positive functioning has been operationalized as participating actively in settings that are typical for children to take part in and that occur on a regular basis. These settings usually include home, school, and community settings. The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC)Citation2 regards families as the natural environment for the growth and well-being of children (UN, 1989, art 23). Behaviors that are established in adolescence can continue into adulthood and affect issues such as mental health, development of health complaints, and alcohol and tobacco use.Citation3 In the home, participating in domestic life activities is crucial for children’s opportunities to learn new skills and develop meaningful relationships with others. Within domestic life, children have the opportunity to participate in different activities such as doing household chores, interacting with adults, and spending time with friends. This is also demonstrated in a study by Law et al.Citation1 in which the home environment was found to be one important factor affecting people’s health during childhood and adolescence. Participation is both as a means and an end in relation to activity competence (Imms et al.).Citation4 Participating daily in household tasks with parents and siblings offers potential situations for increasing the child’s activity competence in performing household tasks that children are expected to perform independently as adults.Citation5 According to Sheldon, Ryan, Deci, and Kasser,Citation6 learning how to be self-dependent is an important aspect of well-being in adulthood. Self-care and household work are areas of functioning that have been reported as relevant for mental health in adolescents.Citation7 These areas of functioning are also represented in the International Classification of Functioning (ICF) core sets for adults with mental health diagnoses such as depression and ADHDCitation8 and can be interpreted as a shift toward the role of adult. The content of screening instruments related to mental health and quality of life mirrors this shift,Citation9 for example, DISABKIDSCitation10 and the WHODAS 2.0.Citation11 Regarding such instruments, items focused on domestic life are usually represented in instruments aimed at adults but not in instruments aimed at children.Citation12

Establishing peer relations is crucial for young people and may also have a long-term effect on social adjustment.Citation13 Interactions with family members and friends give a frame for acquiring skills important later in life.Citation14 Solish et al.Citation15 investigated participation in children with and without disabilities in social, recreational, and leisure activities. They found that children without disabilities tend to spend time in more social and recreational activities and, hence, had more friends than their peers with disabilities. Friendship is associated with high levels of school adjustment, happiness, self-esteem,Citation16 and positive development. Having friends also generates more frequent opportunities to take part in desired activities.Citation17 AdolfssonCitation18 concludes that how to begin and maintain relationships with friends is particularly important for children with disabilities, not only as an important everyday life situation but also because it generates opportunities for participation in a wide set of activities.

Adolescence is often defined as a transition from childhood to adult life. Therefore, when the participation of adolescents in both social interaction and domestic life is studied longitudinally, it can increase the knowledge about participation as an expression of health in this transition. Several contemporary studies focus on the construct of participation.Citation18–Citation21 Common to most definitions of participation is that they focus on involvement in life situations. Some studies primarily include children with disabilities or have children with typical development as a control group (e.g., Ullenhag et al.).Citation22 However, few studies include total populations and compare participation of adolescents with and without impairments or long-term health conditions in the population.

The operationalization of participation within this study

Participation is the key construct within the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health for Children and Youth (ICF-CY) classification. The ICF-CY defines participation as an individual’s involvement in a life situation. Life situations are episodes occurring in natural situations where children spend time.Citation14 Everyday life situations have been defined as “routines/activities that are frequently occurring, comprise sequences of actions, can be accomplished using a variety of tasks, and are goal-directed with meaning for the children” (Adolfsson, p. 36).Citation18 Eriksson and GranlundCitation23 define participation as “a feeling of belonging and engagement experienced by the individual in relation to being active in a certain context.” This definition is consistent with previous research highlighting the importance of considering children’s experience when describing a child’s life situation.Citation24,Citation25 This study investigates self-reported participation (measured as frequency of attendance and perceived importance) in domestic life and the activities of peer relations as defined by the Activity and Participation domains within the ICF-CY.Citation14 The ICF-CY is an example of a biopsychosocial model that contains two dimensions, the person dimension and the environmental dimension. A child’s functioning according to the person dimension is highly dependent on physical and social environments. A central aspect of using a biopsychosocial model such as the ICF-CY is to study the complex relation between adolescents’ environments and their participation using a common terminology.

Participation dimensions

According to Granlund et al.,Citation19 participation consists of two dimensions, presence (i.e., physically being there) and engagement (i.e., expressions of involvement).Citation26 The ICF-CY definition of participation includes the aspect of performance, defined in the ICF-CY as what the individual actually does within specific environments or situations, that is, the “being there” dimension but not the perception of involvement (e.g., the experience of participation, such as affect or motivation).Citation4,Citation14,Citation26,Citation27 Patterns of participation vary across ages and with life roles, and thus, they change over time, especially in transition to adulthood, that is, adolescence. Jarus et al.Citation28 have examined changes in participation patterns in adolescence. Both frequency of attendance and level of involvement in activities vary with age, as do the actual activities available. In a recent conceptual paper by Imms et al.,Citation4 focusing on the participation construct and the interrelationships between participation and the activity and body function components of the ICF-CY, a family of participation-related constructs is presented with the aim to promote conceptual clarity and consistency in the application of the participation construct. According to Imms et al., attendance and involvement constitute key elements and, hence, sub-dimensions of the participation construct. Attendance is defined as the frequency, duration, and diversity of attending an activity. Involvement is defined as the experience of participating while attending and the perceived importance of the activity. Involvement can be operationalized as the actual engagement in the activity while being there but also as the perception of being involved in the activity in post hoc ratings, for example, enjoyment or the rated importance of being involved in the activity. When performing research that addresses the participation construct, a clear description of the measures through which the concept of participation is operationalized is crucial. In this study, the two dimensions of participation in domestic life and peer relations are operationalized into a measure of frequency of attendance and a measure of involvement. Examples could include how often one performs domestic life activities, and a measure of involvement operationalized as the perceived importance of involvement in the domestic activity as rated by the person. By addressing not only participation as a universal construct but also with its sub-dimensions, the subjective experience of involvement is taken into consideration. The two dimensions of participation are probably influenced by partly different factors,Citation20 which is why the present study focuses both on the frequency of attendance in domestic life and within peer relations and the perceived importance of being involved in these two areas of participation.

Individual factors related to participation

Adolescence can be defined as the period in life between 10 and 19 years and is characterized by physical, emotional, and psychological growth.Citation29 The major developmental challenge within adolescence is to negotiate successfully the changes associated with this period of life and at the same time preserve one’s sense of self. During adolescence, mental functions related to the awareness of one’s identity, one’s body, and one’s position in relation to time and one’s environment develop rapidly.Citation14 Adolescence is a time in life associated with special stress of different kinds such as physical and psychological changes. Stress during adolescence may have later consequences on mental health, although this is not the case for all individuals and responses to stress vary widely.

Pubertal growth is associated with bodily changes, and, psychologically, adolescents face challenges related to the transition from childhood to a more independent adulthood. Adolescents negotiate these challenges in various ways. Some do well, while others might face stress-related disorders. Within adolescence, studies of time and time use, as well as time pressure, investigate in what way adolescents allocate their time on a daily basis. Such studies can be helpful to increase knowledge about identity development in which adolescents explore possibilities for different social roles and future expectations.Citation29 Other important factors associated with adolescence are social and cultural values such as norms and values related to physical size, body shape, and gender stereotypes.Citation30 The experience of how one perceives oneself in relation to others might have an impact on different behaviors such as choice of peers or activities in which one takes part.Citation31 Participation for adolescents often differs due to individual characteristics such as an impairment or long-term health condition. Despite sharing the same expectations and desires as adolescents without impairments or long-term health conditions, children and adolescents with impairments or long-term health conditions often tend to spend more time at home and less time with peers.Citation32

This study involves adolescents with and without impairments or long-term health conditions. According to the ICF, an impairment is defined as a reduction of intellectual, mental, or physical function.Citation26 Long-term health conditions can be defined as conditions that should have been present for more than three months, cannot be resolved spontaneously, and are rarely completely cured.Citation33 In medical health care systems, a diagnosis is central in for research concerning aetiology and treatment. However, according to Lollar et al., knowledge about how a person functions in life situations can supplement the diagnosis when addressing the consequences of long-term health conditions and disabilities. Research has shown that diagnosis does not predict well-being in adolescents but, instead, how they experience everyday functioning.Citation34

Activity and environmental factors affecting participation

The ICF defines environmental factors as “the physical, social, and attitudinal environment in which people live and conduct their lives” (WHO, Citation2001, p. xvi). Understanding participation requires an understanding of the influence that family and others in the immediate environment (including siblings and parents) have on everyday functioning. Having a close relationship with relatives as well as healthy and open communication are important factors promoting health and well-being in adolescence.Citation35 During one’s life span, everyday life situations change in content, number, and complexity from the relationship with a primary care-giver to social play and peer relationships.Citation14 Also, the relationship with siblings has a significant influence since siblings represent some of the first people to whom a child is exposed. Sibling interactions represent the first experienced models of interpersonal interactions outside parent-child interactions. Also, sibling relationships are sometimes the longest lasting relationships and could, if sustained, be a source of support throughout life.Citation36 Probably, a person’s frequency of attendance and involvement while attending activities will vary between different everyday activities such as domestic life and peer relations due to both individual and environmental characteristics.Citation37,Citation38 Thus, participation is better described as a profile of everyday functioning.Citation39

Participation for an individual can be seen as a profile of functioning in different types of activities where both measures of attendance and involvement (perceived importance) need to be considered for every activity. One way to increase the understanding of participation profiles is to identify homogeneous groups of persons sharing participation profiles in activities and then to analyze what factors characterize these groups of persons sharing participation profiles. Profiles will vary between individuals, depending on several factors, of which impairments and long-term health conditions, as a group, are only one. Persons having the same participation profile probably also share some factors influencing the level and shape of their profile.

Purpose

The purpose of this study is to identify how individual factors (related to body function and activity performance) and factors within the family environment relate to self-reported participation cluster profiles of attendance and perceived importance in domestic life and interpersonal interactions and relations (peer relations) as defined by the ICF-CY.Citation14

The following research questions were addressed:

What are the common participation cluster profiles based on the frequency of attendance and perceived importance within the participation domains domestic life and interpersonal interactions and relations (peer relations)?

What are the body-function, activity, and environmental factors that characterize those adolescents who share membership in the participation cluster profiles?

Are adolescents with impairment or long-term health conditions over-represented in certain participation cluster profiles?

Methods

Study design

This is a cross-sectional study using self-reported data from the first of five data collections within the ongoing Swedish multidisciplinary research program Longitudinal Research on Development in Adolescence (LoRDIA) that uses a prospective longitudinal cohort design. Data was collected in Swedish compulsory schools and compulsory schools for students with intellectual disabilities in four communities. The Regional Research Review Board in Gothenburg ethically approved the LoRDIA research program and data collection procedure (No. 362–13; 2013–09-25).

Participants

Data were collected in 2013 and 2014. In total, 33 schools and 128 classes participated in the study. The total population of 2,021 students in 6th grade (51.5%) and 7th grade (48.5%) with ages 12–14 in four municipalities in south and southwest of Sweden were invited to participate in the study. The four municipalities have between 9,000 and 36,000 inhabitants and are geographically relatively close. Also, these municipalities were chosen because they represent variations in rural and urban density. Two of the municipalities (A and B) have a relatively high degree of internal school migration; for example, students from the minor municipality (B) usually attend senior high school in the somewhat larger municipality (A). Both municipalities are industrial and relatively small. Municipality C is somewhat larger than A and B and close to Sweden’s second largest city, while D is smaller and more rural than A, B, and C.Citation40 Of the 1,520 participants, 1,378 used the original form of the LoRDIA questionnaire, and 142 students used an adapted version (see further descriptions of the questionnaires in the instrument/measures section). Six percent of the participants were born outside Sweden, and 16.9 percent spoke languages other than Swedish at home. The mean age was 13 years (SD = .59). Most students lived together with both parents (79.9%), 18.4 percent lived with either mum or dad, while 0.9 percent of the students lived in a foster family or with another person. The sample consisted of a relatively even distribution of gender with 769 girls (50.6%) and 751 boys (49.4%).

Attrition

Of the total cohort of 2,021 students, 116 chose not to participate, and 202 students were not given consent from their care-givers, giving a response rate of 84% (n = 1703). At the time of data collection, 183 students were not present. Missing data analysis has been carried out where those without care-giver or own consent were compared with all others based on register data on absenteeism and grade point average (GPA) for each school year for which data were collected. No significant differences in either of these were found. The attrition rate is evenly distributed in three of the four included municipalities and some percent less in one of the municipalities.

Instruments

The data were collected through self-report questionnaires. The questionnaire contains questions regarding identity of the person; socio-demographic data and family structure; perceptions of family economy; perceptions of self-body and puberty; leisure time activities; peer network and quality of peer relations; family relations and parenting models; sibling relations; school behaviors and relations to teachers; experiences of harassments; use of tobacco, alcohol, and drugs; criminal behaviour; family coherence and support; parental use of tobacco, alcohol, and drugs; and parental emotional problems. The items used in this study are originally used in scales previously used and developed by ArvidssonCitation41 as well as Stattin and KerrCitation42 and Galambos et al.Citation43 For further information on the questionnaires used, please see Gerdner et al.Citation40 Several tests concerning the psychometric property of the questionnaires (the original version and the adapted version) have been performed, and the results show that the psychometric properties of the questionnaire parts are satisfactory with Cronbach alpha-values between .7 and .8.Citation40 An adapted version of the original questionnaire was developed and tested to make the questionnaire more adequate for students with intellectual disabilities in terms of language and the amount of response options. For the adaptations, strategies recommended for young children or children and youth with cognitive impairments were used (Nilsson et al.)Citation44 (such as administering the questions in a structured review format, making the wording more concrete, and using a three-step Likert scale). Out of all participating students, 142 used this version. The adapted version consists of the same questions, although with simplified language (e.g., no subordinate clauses or negations) except one question that was removed after the pilot studies due to its complexity that was assumed (and confirmed in the pilot testing) to be too abstract for the students enrolled in the compulsory school for students with intellectual impairments.

Before carrying out any further analysis, the original version and the adapted version of the questionnaire were merged into one data file where all five-point Likert scales in the original version of the questionnaire were reduced a three-point Likert scale where the median value was kept unchanged (Nilsson et al.).Citation44 The values below or above the median were replaced by one lower and one higher value, respectively. For example, the two response alternatives “never” and “seldom” were merged into the response alternative “seldom,” whereas the response alternatives for “often” and “always” were merged into the response alternative “often.”

Procedure

The data were collected in the schools, and the questionnaire took 60–90 minutes to complete. Members from the research team were present in the classrooms to provide support if necessary. For some of the students with intellectual disabilities or students having another language spoken at home, additional time (approximately 30 minutes) was required. The participants filled in the questionnaires in their classrooms at their desks and could ask questions (e.g., regarding meaning of words). A few exceptions for students with intellectual disabilities were made, for example, where a staff member of the research team visited one person who was given the opportunity to fill in the questionnaire at home. The students were also able to take at least one break and were offered refreshments while completing the form.

Cluster variables used in the analysis

Based on the fact that most previous studies focus on school activities or participation in leisure activities (Adair et al.),Citation45 this study focuses on participation in domestic life and peer relations. The variables representing participation were created partly as a result of an earlier study (Augustine et al.)Citation46 in which all items within the LoRDIA questionnaire were linked to ICF-CY codes. The codes assigned to participation in domestic life and peer relations were, in this study, decided to be the outcome variables, and factors assumed to affect participation related to body functions, activity performance, and environmental level were, in this study, referred to as independent variables (these are further described below).

The variables defining the clusters were four indices measuring participation (in this study defined as those questions from the questionnaire that were assigned codes related to chapters 6–9 within the activity and participation component in the ICF-CY); namely, (1) frequency in domesticFootnote1 life (chap. 6 within the ICF-CY) (α .54), (2) perceived importance of participating in different domestic life activities (chap. 6 within the ICF-CYFootnote2 ) (α .62), (3) frequency in peer relationsFootnote3 (chap. 7 within the ICF-CY) (α .35) in this study referred to as peer relations, and (4) perceived importance of interpersonal interactions and relationships/peer relations (chap. 7 within the ICF-CY) (α .31). Because of focusing on participation rather than activity competence, it was decided that items focusing on discrete skills that could be interpreted as activity competence would be included as attendance and importance items. The wording of the items concerned the frequency of attending the activities and the perceived importance of the activities rather than the independence in performing the activities.

The index concerning frequency in domestic life contained the following questions: “How often do you help out at home?,” “How often do you do grocery shopping?,” “How often do you prepare a meal?,” and “How often do you wash your clothes?.” The index regarding frequency in interpersonal interactions and relationships (peer relations contained the following questions: “How often do you make new friends?,” “How often do you get along with friends?,” and “How often do you spend time with girl- or boyfriend?.” The involvement index regarding domestic life and interpersonal interactions and relationships contained the same items as the frequency index, but here the question was whether the items were considered important or not to participate in. The response scale for the frequency indices was a three-point Likert scale where 1 = never, 2 = sometimes, and 3 = Often. For the involvement indices regarding whether the items were considered important or not, the response scale was also a three-point Likert scale where 1 = no, 2 = not really, and 3 = yes.

Independent variables

Body functions in this study are represented by an index regarding experience of self- and time functions (b180) (α 0.70). For example, respondents were asked to complete statements such as the following: “Compared to peers at the same age, I feel younger/the same age/much older,” and “My friends treat me as if I were much younger/the same age or much older than I am.” The activity domain is represented by an index regarding handling stress and psychological demands (d240) (α 0.44). For example, respondents were asked to complete this statement: “How often do you handle time pressure?” Another index regarding discussion (d355) (α 0.67) asked, for example, “How often do you participate in a discussion (reasoning, small talk, etc.)?” and “How important do you consider it to participate in a discussion?.” The following environmental domains are covered: First, an index labeled support from siblings (e3) (α 0.86) with questions such as “If I argue with my parents, my sibling supports me” and “If I would get into trouble, I could turn to my sibling for help.” Second, an index labeled “atmosphere in the family” including individual attitudes of immediate family members (e410) (α 0.79) poses questions that concern parental control (i.e., the extent to which parents require their child to ask for permission before going out and insists on getting information on their children’s whereabouts. The index also concerns questions referring to parental solicitation (the extent to which parents actively seek information on what their children do) and, finally, questions on child disclosure, that is, the extent to which children spontaneously disclose information on their whereabouts).Citation42 Examples of questions in this index are “How often do your parents ask you to tell about things going on in your leisure time?,” “Do your parents know how you spend your money?,” or “Do your parents always demand to know where you are in the evenings, whom you meet with and what you do together?.”Citation47 All indices were investigated for factorability using principal component analysis, and internal consistency was measured by calculating the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient.

Also, the adolescents were asked whether they had an impairment or long-term health condition such as diabetes, visual impairment, motor impairment, autism, and so forth. They were then divided into three groups for the current study (no impairment or long-term health condition, neurodevelopmental disorder,Citation48 and physical impairments).

Data analysis

A hierarchical cluster analysis (Wards method) was performed to identify underlying cluster patterns within the data (e.g., homogeneous groups of individuals with the same participation profiles).Citation49 The nine-cluster solution was chosen after considering explained variance, interpretability, and having a meaningful distribution of students within the different clusters.Citation49 To evaluate the chosen cluster solution, a random procedure was performed three times where a third of the randomly chosen sample’s means were compared to the means of the total sample, indicating a satisfactory degree of similarity with the total sample. A centroid procedure was performed to evaluate the structural stability between the random set and the original set. Pairwise matching to identify the similarity between clusters was defined by the squared Euclidean distance (ESS) (.5), and the three sets of random samples had a mean of (0.043, (0.061), and (0.049), respectively.

The cluster groups were then compared by using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the Scheffe post hoc test. The nine cluster groups were investigated regarding the independent variables (the indices for body function, activity, and environment). Also, comparisons of background data such as gender, language spoken at home, nationality, and type of impairment were investigated by the use of X2 tests. The person-oriented analysis was carried out with the statistical package SLEIPNER, version 2.1. Further analyses regarding categorical data and continuous data were performed using the IBM Statistics SPSS version 21.

Results

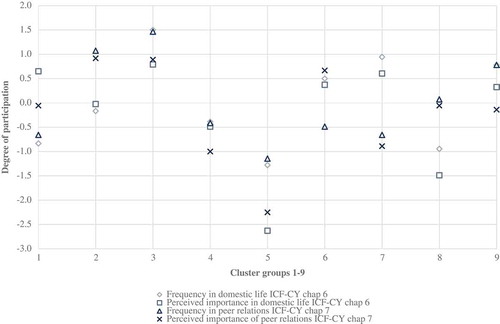

A nine-cluster solution was derived from the variables defining the cluster analysis (the indices regarding frequency and perceived involvement in domestic life and peer relations). The choice of solution was based on statistical criteria such as degree of explained variance (60.49), a sharp increase in error sum-of-squares (ESS) between the 8 and 9 cluster solution (31.15–48.34), and the level of homogeneity within the clusters Citation49 (for more information on the homogeneity coefficient values for each cluster, please see ). shows an illustration of the participation profiles (with standardized values). provides an overview of the cluster labels. also illustrates significant differences between the clusters regarding the independent variables (the indices measuring body functions, activity, and environment). presents demographic information on the adolescents in the clusters. All values were significant at p < 0.001 level.

Table 1. Overview of cluster labels.

Table 2. ANOVA results including means and standard deviations for independent variables for the nine clusters and differences between clusters.

Table 3. Demographic information on adolescents in the nine clusters.

Figure 1. Patterns of participation regarding frequency and perceived importance in domestic life and peer relations.

Participation profiles

The first cluster (n = 176) was labeled Higher perceived importance than frequency of attending where the frequency in domestic life and peer relations were rated lower (1 SD below sample mean) than the perceived importance of domestic life and peer relations. The second cluster (n = 220) was labeled Low participation in domestic life but high participation in peer relations. This cluster contained adolescents who rated both frequency and perceived importance of domestic life low, whereas both frequency and perceived importance of peer relations were rated high. The third cluster (n = 81) was labeled High level of participation, having the highest frequency and perceived importance pattern of the nine clusters. The adolescents in the fourth cluster (n = 199) labeled Relatively low general level of participation received relatively low scores on both frequency and perceived importance of domestic life and peer relations. The fifth cluster (n = 39) that was labeled Very low level of participation both in domestic life and in peer relations had children with the lowest scores regarding both frequency and perceived importance of domestic life and peer relations. The adolescents in the sixth cluster (n = 234) labeled High participation in domestic life, low frequency of participation with peers rated the perceived importance of domestic life higher, but less frequently participated in peer interactions.

The seventh cluster (n = 110) labeled High-level domestic activity participation contained adolescents who received high scores on both frequency and perceived importance in domestic life in comparison to the lower levels of frequency and perceived importance in peer relations. Adolescents in the eighth cluster (n = 132) labeled Low participation in domestic life had low ratings of both frequency and perceived importance in domestic life, a higher frequency in peer relations, and an average level of perceived importance in peer relations. The ninth cluster (n = 158) was labeled High frequency of participation with lower level of perceived importance in peer relations. Adolescents in this cluster received high scores of frequencies in both domestic life and peer relations, a high level of perceived importance in domestic life, and an average level of perceived importance in peer relations.

Cluster characteristics of body function, activity, and environmental factors

Body functions (experiences of time and self)

Adolescents in clusters 1 and 3 differed regarding perceived body functions. Adolescents in cluster 1 felt younger in comparison to the adolescents in cluster 3 and believed that they looked younger than other adolescents in the same age group. Members of cluster 1 also perceived that they were treated as younger than their actual age that adolescents in cluster 3 did not perceive.

Activity (stress and discussion)

No differences were found between the clusters regarding experience of stress. Concerning discussions, several cluster profiles differed in how the adolescents perceived that they generally took part in discussions and how they rated the importance of this. Adolescents in clusters 1, 4, 8, and 9 took part in discussions to a low degree and perceived that it was not important. Adolescents in clusters 2, 3, and 6 more frequently took part in discussions and considered it important. The adolescents in the seventh cluster did not differ from the other clusters in taking part in discussions and the ratings of importance of taking part in discussions.

Environment (support from siblings and atmosphere in the family—control and demands)

The cluster profiles differed in the way the adolescents experienced support from siblings as well as the atmosphere within the family. Adolescents in clusters 1, 2, 3, and 6 perceived having more support from siblings. Adolescents in these clusters also experienced an average level of control and demands from their parents (cluster 1 and cluster 3) or less than average control and demands from their parents (cluster 2). Adolescents in clusters 4, 5, 8, and 9 experienced less support from their siblings. Adolescents in these clusters experienced about average control and demands (cluster 4) or as being more controlling and filled with demands (clusters 5 and 8). An exception is cluster 9 whose members experienced fewer demands.

Demographic characteristics

Girls were over-represented in five of the clusters (2, 3, 6, 7, and 9). All clusters had adolescents who reported having siblings. The number and type of conditions related to the different groups of impairments that were applied in this study are illustrated in . Adolescents with impairments or long-term health conditions were represented in all clusters. The frequency of neuropsychiatric impairments varied between 3.4% and 11.0% in the clusters. Physical impairments varied between 29.1% and 39.7% in the clusters. The representation of adolescents who reported having both neurodevelopmental and a physical impairment accounted for 8.2–15.1% in the clusters.

Discussion

Ullenhag et al.Citation22 argue that studies in which children’s own voices are presented are essential in understanding the multidimensional concept of participation. This study contributes to the existing literature by adding data on subjective ratings from Swedish adolescents with and without impairments and/or long-term health conditions. The study aimed at identifying patterns of participation in domestic life and peer relations. Also, body, activity, and environmental factors differing between the clusters were identified.

Participation restrictions

The perceived importance ratings for all clusters regarding peer relations are higher than the ratings regarding perceived importance in domestic life. Given the age of the adolescents, the results indicate that getting along with friends is perceived as more important than helping at home. Although the importance of peer relations is rated high for all the clusters, the ratings of frequency, for example, how often one gets new friends or gets along with friends, is lower. This might be due to the type of questions asked (How often do you get new friends and how often do you get along with friends?). Another explanation might be that the respondents would like to interact more with peers than they do. Arvidsson et al.Citation25 have proposed that when self-ratings are used to map participation, participation restriction can be defined as low frequency of attendance in activities considered important to attend. The index for peer relations included one question on how often one spends time with one’s girlfriend or boyfriend. Adolescents in all the clusters find this important but, due to their age, they probably do not yet have an established girlfriend or boyfriend.

Personal factors influencing participation

Regarding the level of profiles, the largest differences were identified between cluster 5 with a low level and cluster 3 with a high level. The participation profile for the adolescents in the third cluster indicated the highest level of frequency and perceived importance in both domestic life and peer relations. In addition to a supportive family environment, this cluster contained more girls than expected and more children with neuropsychiatric impairment than expected. King et al. found that girls tend to take part more in activities based on social skills, and this—along with the assumption that children with neuropsychiatric impairments are more dependent on family in social activities and get more support—may explain the result.

Cluster 5 is the smallest cluster in terms of sample size and the cluster with the largest proportion of boys (significantly fewer girls, 28%, than boys, 72%). This cluster had the second highest proportion of members with physical disabilities among the clusters. King et al.Citation24 found gender differences in a study on comparisons of recreational leisure activities for children with and without disabilities. Results demonstrated that boys participated more in physical activities than girls, whereas girls took part more in activities based on social skills and enjoyed these more than boys. McDougall et alCitation50 found that children with chronic physical health conditions experience activity limitations restricting their participation. They also found, in another study, that boys and girls with physical disabilities participate in activities that differ from those of their typically developing peers.Citation51 This would then be in accordance with the present study’s findings that having a physical disability may lead to restrictions on participating in activities in domestic life as well as in interacting with peers.

Role of peer relationships

Five of the clusters (1, 4, 5, 6, and 7) report a low frequency of attendance in peer relations, that is, making new friends, getting along with friends, and spending time with a girlfriend or boyfriend. Except for cluster 6, these clusters also reported low perceived importance in peer relations. According to Masten,Citation52 the establishment of friendship relations with peers represents a critical developmental task during adolescence and is associated with higher levels of psychosocial well-being and positive development.Citation24 It is probably the case that frequency of attendance in contexts containing peers and perceived importance in peer relations form mutual feedback loops in which low attendance or perceived importance lead to low values in the other. King et al.Citation24 found that children without disabilities experienced a larger social world with more intense social participation with non-family members than peers with disabilities. In this study, a relatively high proportion (40%) of the children in cluster 6, who have a low frequency of meeting with peers but not a low perceived importance, reported a physical disability. This might indicate another causal influence with physical disabilities rather than negative feedback loops affecting frequency of peer interaction. Physical disabilities might pose a barrier for spending time with friends and, hence, affect the experience of participation negatively.Citation51,Citation53,Citation54

Sibling, family, and peer influence on participation

In contrast to body function characteristics, family atmosphere and social interaction seem to be important for participation. The index regarding atmosphere in the family concerns parental control, parental solicitation, and disclosure.Citation42 In this study, it seems as though the adolescents who participate frequently and rate perceived importance high in peer relations are more involved in discussions and experience more support from siblings and less parental control (clusters 2, 3, 6). To enhance adolescent participation, real-life experiences involving the family (such as family and recreational activities) are important.Citation55 A possible indicator of family involvement in activities may be less parental control. It is associated with being more active in discussions at home and with experiences of more support from siblings. In well-functioning families, parents seem to decrease control over their children gradually.Citation56 The participants in this study were young adolescents for whom a decrease in parental control also probably has positive effects on participation outside the family. Parental control is related to parental communication. Parental communication is one of the key ways in which the family can act as a protective health asset.Citation57 Parents who provide opportunities for children to take part in, for example, decision making, have children with lower levels of depression in youth and better self-worth.Citation58

In comparison with the low-level cluster 5, adolescents in cluster 3 presented a positive profile of participation with high levels of frequency and perceived importance in both domestic life and peer relations. A high proportion of the adolescents in this cluster have siblings (93.8%). They also rated high participation in discussions. The discussion index concerned how often one takes part in small talk and discussions, and—since this cluster reported that they often did take part in discussions and small talk—it can be assumed that having siblings would increase the frequency of doing so. Also, having siblings might increase the experience of perceived importance within the activity. In this study, perceived importance was used to estimate involvement. Other involvement indicators such as the child’s enjoyment of an activity have indicated the same patterns of relations between interaction and involvement.Citation54

Adolescents in cluster 6 experienced much support from siblings and less parental control. The participation profile was characterized by high frequency and perceived importance regarding ratings in domestic life, low frequency ratings in peer relations but high ratings of perceived importance in peer relations. This was the largest cluster regarding sample size, and there were significantly more girls than expected. The accumulation of support from siblings, parents, and peers is a strong predictor of positive health.Citation59 The more sources of support, the more likely it is that children will experience positive health. This is in line with Stattin and Kerr who concluded in their study from 2000 Citation42 that tracking and surveillance is not the best predictor of efficient parental behavior and that parents get most of their information based on their children’s willing disclosure. They also found that girls seemed freely to disclose more information to their parents than boys, but boys reported having better relationships with their parents than girls. It could be argued that this pattern is common at this age, that is, not feeling overly controlled by parents but having a feeling of support if needed and, at this age, that girls, in particular, tend to spend more time at home with their siblings and parents.

Both frequency of attendance and level of perceived importance, especially in peer relations, seem related to high ratings of discussion, siblings support, and family atmosphere. It can be an indicator of the importance of the aggregated effect of several factors in the home environment on participation. Perhaps the home environment serves as protective factors, which also can minimize the negative influence of type of disability on participation. The results corresponds with the findings presented by Castro and PintoCitation60 arguing that a functional approach to disability should be supported emphasizing the importance of level of engagement (in this study operationalized as perceived importance, i.e., involvement) and environmental factors when determining functioning in children with disabilities.

Methodological considerations

This is a cohort study with a cross-sectional descriptive design in which the focus is to present groups of individuals having homogenous participation profiles and individual factors as well as environmental factors related to the profiles. The present study is one of the research program LoRDIA’s studies aiming at including the total population of adolescents of age 12–13 within the four chosen municipalities. This meant that all adolescents were invited to participate, including those following the syllabus for the adolescents with intellectual disabilities. Several methodological adaptions were, therefore, necessary for all adolescents to be able to answer the questionnaire. The adapted version of the questionnaire was not only beneficial and used for the students following the syllabus for adolescents with intellectual disabilities, but the teachers also recommended it to several students with reading and writing difficulties as well as for students who recently had immigrated to Sweden.

Some possible bias effects should be discussed regarding measurement inaccuracy. The data is based on self-reports, and it was not possible to determine whether the adolescents have an impairment or not.

Studies with a relatively large sample including self-reports in which adolescents with intellectual disabilities also are participating are rare.Citation61 Therefore, this study adds knowledge to the existing research on self-reported everyday functioning for adolescents with and without disabilities. Regarding the clusters derived from the cluster analysis, the homogeneity coefficient (measuring the degree of proximity between cases in the clusters) was above 1 in some clusters. The lower the coefficient, the better the homogeneity in the cluster.Citation62 This was probably a result of the sometimes relatively low internal consistency in the variables forming the clusters (the participation indices regarding domestic life and peer relations) having alpha values between 0.31 and 0.62. This should be taken into consideration when interpreting the results. The low alpha values are most likely a result of the complexity of the concept of participation, and the domains in the ICF-CY reflect this complexity.

Despite the relatively low internal consistency, these indices were kept with reference to the ICF where it is stated that areas related to the close environment such as domestic life as well as informal social relationships reflect important domains of participation.Citation26 The indices were also kept with reference to earlier research using the ICF-CY as a model for defining participation in which the difficulties in separating the activities and participation component (as done in the classification but not in the model) are addressed.Citation63,Citation64 Taking a clinimetric approach into account, one could argue that these indices can be kept since the aim of this approach is to measure a clinical phenomenon that includes several but not always conceptually or empirically related important characteristics of the investigated phenomenon. When using a clinimetric approach, compromises regarding psychometric criteria are sometimes necessary when measuring a phenomenon such as participation. For example, fewer items that are considered important for the phenomenon in focus can be prioritized before a large number of possibly related items.Citation25,Citation65 The complexity of defining the concept of participation should also be addressed. As of today, there is no universally accepted definition of participation (Imms 2015 systematic review). In the present study, the ICF definition of participation has been used.Citation14 This definition represents the societal perspective of functioning. The definition is, however, very broad, which adds to the complexity of measuring participation. According to King et al.,Citation21 appropriate measures of participation are required to cover participation in various life domains. Also, measuring participation in specific life situations such as home and activity settings where children spend time requires a comprehensive understanding of the nature and concept of participation. Participation is tied to a context, that is, specific situations, and therefore, to measure participation in environmental or social contexts, it is also necessary to broaden our understanding of how participation is experienced. Hence, this requires self-reports and not only proxy ratings (i.e., care-giver’s ratings), since self-reports of the experience in a certain context can be different from the care-giver’s perspectives.Citation21,Citation25 In this study, the subjective experience of the involvement dimension of participation has been addressed in terms of self-rated importance in domestic life and peer relations. Importance can, therefore, be seen as an indicator of involvement and, hence, the adolescent’s motivation and previewed need to participate in an activity is addressed.

Conclusion

Interventions aimed at enhancing participation for adolescents with and without disabilities in domestic life as well as in peer relations should focus not only on issues regarding frequency of attendance but also on the subjective dimension of participation, the involvement dimension (in this study measured as perceived importance). Results from this study indicate that it is not solely the type of impairment or long-term health condition that determines cluster membership or level of participation. Frequency of attendance and level of perceived importance, especially in peer relations, seem to be related to high ratings of discussion, siblings support, and family atmosphere. To enhance participation, health problems and impairments within the person are not the only issues that should be addressed. Family and peer influence on participation for adolescents with and without disabilities also needs to be considered.

Future research

Future research can focus on whether the participation profiles demonstrated in this study are consistent over time. Do adolescents stay in the same clusters, and do the same factors within body functions, activity, or environment affect the participation profiles? Moreover, there is a need for further studies of the influence of impairments on participation—studies in which the result of variable-based designs and the result of person-based design rely on the same data.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the students and school staff who participated and facilitated this study, as well as the research assistants who assisted in the data collection within the LoRDIA research program.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 “Areas of domestic life include acquiring a place to live, food, clothing and other necessities, household cleaning and repairing, caring for personal and other household objects, and assisting others” (ICF-CY, p. 167).

2 According to the ICF-CY, chapters 6–9 in the activity and participation component concern life areas and contexts and can be referred to as participation (WHOCitation26).

3 Chapter 7 within the ICF-CY concerns “/…/ carrying out the actions and tasks required for basic and complex interactions with people such as strangers, friends, relatives and family members in a contextually and socially appropriate manner “(ICF-CY, p. 173).

References

- Law M. Participation in the occupations of everyday life. Am J Occup Ther. 2002;56(6):640–49.

- UNICEF. Convention on the Rights of the Child. 1989. https://www.unicef.org/crc/ Accessed 2017 February 4

- Adolescence development. 2017. [accessed 2017 Sep 6]. http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/topics/adolescence/dev/en/.

- Imms C, Granlund M, Wilson PH, Steenbergen B, Rosenbaum PL, Gordon AM. Participation, both a means and an end: A conceptual analysis of processes and outcomes in childhood disability. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2017 Jan; 59(1):16-25.

- Dunst CJ, Bruder MB, Trivette CM, Hamby DW. Everyday activity settings, natural learning environments, and early intervention practices. J Policy Pract Intell Dis. 2006;3(1):3–10. doi:10.1111/j.1741-1130.2006.00047.x.

- Sheldon KM, Ryan RM, Deci EL, Kasser T. The independent effects of goal contents and motives on well-being: it’s both what you pursue and why you pursue it. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2004;30(4):475–86.

- Gustafsson J-E, Allodi Westling M, Åkerman A, Eriksson C, Eriksson L, Fischbein S, Granlund M, Gustafsson P, Ljungdahl S, Ogden T. School, learning and mental health: A systematic review. Stockholm: Kungl. Vetenskapsakademien; 2010.

- Bölte S, Schipper E, Holtmann M, Karande S, Vries P, Selb M, Tannock R. Development of icf core sets to standardize assessment of functioning and impairment in adhd: the path ahead. Eur Adolesc Psych. 2014;23(12):1139–48. doi:10.1007/s00787-013-0496-5.

- Fayed N, De Camargo OK, Kerr E, Rosenbaum P, Dubey A, Bostan C, Faulhaber M, Raina P, Cieza A. Generic patient-reported outcomes in child health research: A review of conceptual content using world health organization definitions. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2012;54(12):1085–95. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2012.04393.x.

- The DISABKIDS Group Europe. The DISABKIDS questionnaires quality of life questionnaires for children with chronic conditions. Lengerich: Pabst Science Publishers; 2006.

- World health organization disability assessement schedule (WHODAS 2.0). [accessed 2017 Sep 5]. http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/whodasii/en/.

- Cieza A, Stucki G. Content comparison of health-related quality of life (hrqol) instruments based on the International classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Int J Qual Life Asp Treat Care Rehabil. 2005;14(5):1225–37. doi:10.1007/s11136-004-4773-0.

- Adolescent health. [accessed 2017 Mar 14]. http://www.who.int/topics/adolescent_health/en/.

- WHO. 2001. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Solish A, Perry A, Minnes P. Participation of children with and without disabilities in social, recreational and leisure activities. J Appl Res Intel Dis. 2010;23(3):226–36. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3148.2009.00525.x.

- Schneider B. Friends and enemies. Routledge; 2014.

- Ullenhag A, Bult MK, Nyquist A, Ketelaar M, Jahnsen R, Krumlinde-Sundholm L, Almqvist L, Granlund M. An international comparison of patterns of participation in leisure activities for children with and without disabilities in Sweden, Norway and the Netherlands. Dev Neurorehabil. 2012;15(5):369–85. doi:10.3109/17518423.2012.694915.

- Adolfsson M. Applying the ICF-CY to identify everyday life situations of children and youth with disabilities [elektronisk resurs]. Jönköping: School of Education and Communication; 2011.

- Granlund M, Arvidsson P, Niia A, Bjorck-Akesson E, Simeonsson R, Maxwell G, Adolfsson M, Eriksson-Augustine L, Pless M. Differentiating activity and participation of children and youth with disability in sweden a third qualifier in the international classification of functioning, disability, and health for children and youth? Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;91(2):S84–S96. doi:10.1097/Phm.0b013e31823d5376.

- Granlund M. Participation - challenges in conceptualization, measurement and intervention. Child Care Health De. 2013;39(4):470–73. doi:10.1111/Cch.12080.

- King G. Perspectives on measuring participation: going forward. Child Care Health De. 2013;39(4):466–69. doi:10.1111/Cch.12083.

- Ullenhag A, Krumlinde-Sundholm L, Granlund M, Almqvist L. Differences in patterns of participation in leisure activities in swedish children with and without disabilities. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36(6):464–71.

- Eriksson L, Granlund M. Perceived participation. A comparison of students with disabilities and students without disabilities. Scand J Disabil Res. 2004;6(3):206–24. doi:10.1080/15017410409512653.

- King G, Law M, Hurley P, Petrenchik T, Schwellnus H. A developmental comparison of the out‐of‐school recreation and leisure activity participation of boys and girls with and without physical disabilities. Int J Dis, Dev Educ. 2010;57(1):77–107.

- Arvidsson P. Assessment of participation in people with a mild intellectual disability. Örebro: Örebro Universitet; 2013.

- World Health Organization (WHO). International classification of functioning, disability and health: Icf. World Health Organization; 2001.

- Imms C, Adair B, Keen D, Ullenhag A, Rosenbaum P, Granlund M. ‘Participation’: A systematic review of language, definitions, and constructs used in intervention research with children with disabilities. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2016;58(1):29–38. doi:10.1111/dmcn.12932.

- Jarus T, Anaby D, Bart O, Engel-Yeger B, Law M. Childhood participation in after-school activities: what is to be expected? Br J Occup Ther. 2010;73(8):344–50. doi:10.4276/030802210X12813483277062.

- Hilbrecht M, Zuzanek J, Mannell RC. Time use, time pressure and gendered behavior in early and late adolescence. Sex Roles. 2008;58(5–6):342–57.

- Arnold LE. Childhood stress. Toronto: John Wiley & Sons; 1990.

- Health for the world’s adolescents: A second chance in the second decade: summary. 2014. http://apps.who.int/adolescent/second-decade/.

- Brown M, Gordon WA. Impact of impairment on activity patterns of children. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1987;68(12):828–32.

- Van Der Lee JH, Mokkink LB, Grootenhuis MA, Heymans HS, Offringa M. Definitions and measurement of chronic health conditions in childhood: A systematic review. JAMA. 2007;297(24):2741–51. doi:10.1001/jama.297.24.2741.

- Lollar DJ, Hartzell MS, Evans MA. Functional difficulties and health conditions among children with special health needs. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):e714–22. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-0780.

- Gauze C, Bukowski WM, Aquan-Assee J, Sippola LK. Interactions between family environment and friendship and associations with self-perceived well-being during early adolescence. Child Dev. 1996;67(5):2201–16. doi:10.2307/1131618.

- Kryzak LA, Jones EA. Sibling self-management: programming for generalization to improve interactions between typically developing siblings and children with autism spectrum disorders. Dev Neurorehabil. 2017;1–13. doi:10.1080/17518423.2017.1289270.

- Coster W, Law M, Bedell G, Khetani M, Cousins M, Teplicky R. Development of the participation and environment measure for children and youth: conceptual basis. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(3):238–46. doi:10.3109/09638288.2011.603017.

- Coster W, Bedell G, Law M, Khetani MA, Teplicky R, Liljenquist K, Gleason K, Kao Y-C. Psychometric evaluation of the participation and environment measure for children and youth. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2011;53(11):1030–37. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2011.04094.x.

- Almqvist L, Granlund M. Participation in school environment of children and youth with disabilities: A person‐oriented approach. Scand J Psychol. 2005;46(3):305–14.

- Gerdner A, Falkhe C, Granlund M, Skårner A. Longitudinal research on development in adolescence (lordia)- a programme to study teenager’s social network, substance misuse, psychological health and school adjustment. Research project plan. School of Health Sciences, Jönköping: Jönköping University and Gothenburg University; 2013 Jan 14.

- Arvidsson P, Granlund M, Thyberg I, Thyberg M. International classification of functioning, disability and health categories explored for self-rated participation in swedish adolescents and adults with a mild intellectual disability. J Rehabil Med. 2012;44(7):562–69. doi:10.2340/16501977-0976.

- Stattin H, Kerr M. Parental monitoring: A reinterpretation. Child Dev. 2000;71(4):1072–85.

- Galambos NL, Kolaric GC, Sears HA, Maggs JL. Adolescents’ subjective age: an indicator of perceived maturity. J Res Adolescence. 1999;9(3):309–37.

- Nilsson S, Björkman B, Almqvist A-L, Almqvist L, Björk-Willén P, Donohue D, Enskär K, Granlund M, Huus K, Hvit S. Children’s voices–differentiating a child perspective from a child’s perspective. Dev Neurorehabil. 2015;18(3):162–68.

- Adair B, Ullenhag A, Keen D, Granlund M, Imms C. The effect of interventions aimed at improving participation outcomes for children with disabilities: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2015;57(12):1093–104.

- Augustine L, Lygnegård F, Granlund M, Adolfsson M. Linking youths’ mental, psychosocial, and emotional functioning to ICF-CY: lessons learned. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;1–7. doi:10.1080/09638288.2017.1334238.

- Field A. Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. London: Sage; 2013.

- American Psychiatric Association. 2013. Neurodevelopmental Disorders. http://dsm.psychiatryonline.org/doi/abs/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.dsm01. Accessed 2017 February 4.

- Bergman LR, Magnusson D, El Khouri BM. Studying individual development in an interindividual context: A person-oriented approach. Mahwah: Psychology Press; 2003.

- McDougall J, King G, De Wit DJ, Miller LT, Hong S, Offord DR, Laporta J, Meyer K. Chronic physical health conditions and disability among canadian school-aged children: A national profile. Disabil Rehabil. 2004;26(1):35–45. doi:10.1080/09638280410001645076.

- King G, McDougall J, DeWit D, Petrenchik T, Hurley P, Law M. Predictors of change over time in the activity participation of children and youth with physical disabilities. Child Health Care. 2009;38(4):321–51.

- Masten AS, Coatsworth JD, Neemann J, Gest SD, Tellegen A, Garmezy N. The structure and coherence of competence from childhood through adolescence. Child Dev. 1995;66(6):1635–59.

- King G, Law M, Hanna S, King S, Hurley P, Rosenbaum P, Kertoy M, Petrenchik T. Predictors of the leisure and recreation participation of children with physical disabilities: A structural equation modeling analysis. Child Health Care. 2006;35(3):209–34.

- Law M, Anaby D, Teplicky R, Khetani MA, Coster W, Bedell G. Participation in the home environment among children and youth with and without disabilities. Br J Occup Ther. 2013;76(2):58–66.

- Chiarello LA, Bartlett DJ, Palisano RJ, McCoy SW, Fiss AL, Jeffries L, Wilk P. Determinants of participation in family and recreational activities of young children with cerebral palsy. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;38(25):2455–68.

- Eccles JS, Early D, Fraser K, Belansky E, McCarthy K. The relation of connection, regulation, and support for autonomy to adolescents’ functioning. J Adolesc Res. 1997;12(2):263–86.

- Fenton C, Brooks F, Spencer NH, Morgan A. Sustaining a positive body image in adolescence: an assets‐based analysis. Health Soc Care Community. 2010;18(2):189–98.

- Smetana JG, Campione‐Barr N, Daddis C. Longitudinal development of family decision making: defining healthy behavioral autonomy for middle‐class african american adolescents. Child Dev. 2004;75(5):1418–34.

- Molcho, M., Nic Gabhainn, S., & Kelleher, C. (2007). Interpersonal relationships as predictors of positive health among Irish youth: The more the merrier. Irish Medical Journal, 100(8):33–36.

- Castro S, Pinto A. Matrix for assessment of activities and participation: measuring functioning beyond diagnosis in young children with disabilities. Dev Neurorehabil. 2015;18(3):177–89. doi:10.3109/17518423.2013.806963.

- Wendelborg C, Kvello Ø. Perceived social acceptance and peer intimacy among children with disabilities in regular schools in norway. J Appl Res Intel Dis. 2010;23(2):143–53.

- Bergman LR, David M. A person-oriented approach in research on developmental psychopathology. Dev Psych. 1997;9(2):291–319.

- Maxwell G, Alves I, Granlund M. Participation and environmental aspects in education and the ICF and the ICF-CY: findings from a systematic literature review. Dev Neurorehabil. 2012;15(1):63–78. doi:10.3109/17518423.2011.633108.

- Maxwell G, Augustine L, Granlund M. Does thinking and doing the same thing amount to involved participation? Empirical explorations for finding a measure of intensity for a third ICF-CY qualifier. Dev Neurorehabil. 2012;15(4):274–83.

- Ullenhag A. Participation in leisure activities of children and youths with and without disabilities. Karolinska Institutet. Stockholm: Dept of Women’s and Children’s Health; 2012.